Germanicus campaigns

| date | AD 14-16 |

|---|---|

| place | Northern Germania between the Rhine and Weser-Leine region |

| output | Successful military resistance of the Germanic peoples against attempts of Roman submission; Retreat of the Romans to the Rhine border |

| consequences | End of the Augustan German Wars; de facto Roman renunciation of control of the Germania on the right bank of the Rhine |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

Germanic tribal coalition under the leadership of the Cherusci |

|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| around 70,000 | unknown |

| losses | |

|

20,000 to 25,000 |

unknown |

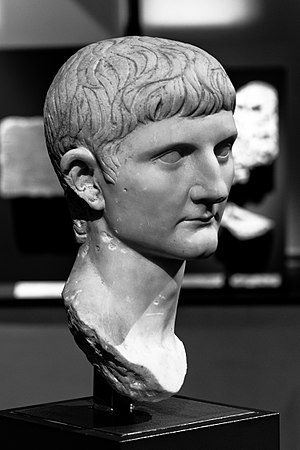

The Germanicus campaigns were Roman military operations from AD 14 to 16 against a coalition of Germanic tribes on the right bank of the Rhine . The campaigns are named after Nero Claudius Germanicus (* 15 BC; † 19 AD), a great-nephew of Augustus . The main opponents were the Cheruscans under the leadership of Arminius (* around 17 BC; † around 21 AD).

The offensives are considered the climax and end point of the Augustan German Wars , which took place in 12 BC. BC by Nero Claudius Drusus , the father of Germanicus. The offensives were carried out with enormous effort - Germanicus commanded the largest Roman army of the time with eight legions . The campaigns were preceded by the crushing defeat of the Roman governor Varus ( battle in the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD) and the loss of almost all Roman positions on the right bank of the Rhine. The main goals of the war were therefore to restore Roman sovereignty in Germania and to punish the rebels.

Military action began in the fall of 14 AD with a raid on the Martians tribe . A naval landing with 1,000 ships in the mouth of the Ems in the summer of 16 AD and the subsequent battle of Idistaviso , the largest battle of the Augustan Teutonic Wars , are considered the military highlight of the campaigns . After heavy Roman losses, the fighting ended in the autumn of 16 AD against the will of Germanicus on the energetic direction of Emperor Tiberius (14 to 37 AD). Roman propaganda turned the cessation of fighting into a victory, Germanicus held a brilliant triumphal procession .

The result of the Germanicus campaigns was the fact that the Romans renounced military control of Germania and the legions withdrew to the Rhine line. Arminius was therefore considered by the Roman historian Tacitus , the main source of the Germanicus campaigns, as the “liberator of Germania” (liberator Germaniae) .

Sources

The annals of Tacitus

The ancient authors hardly went into the campaigns of Germanicus and only reported on the triumphal procession of Germanicus in AD 17, for example Cassius Dio or Strabo . The campaigns were not considered to be memorable because - contrary to the image that the victory propaganda tried to convey - they were unsuccessful. Publius Cornelius Tacitus (* around 58 AD; † around 120) was aware of the futility of the Germanicus campaigns. Nevertheless, he devoted large parts of the first two books of his annals to these campaigns and left behind one of the most detailed descriptions of ancient war campaigns.

The annals describe Roman history from the death of Augustus (August 19, 14 AD) and the rise of Tiberius. This literarily outstanding late work by Tacitus was created around 100 years after the events. The sources that Tacitus used for the creation of the Germanicus passages are lost today. Presumably he had the 20 books comprehensive font Bella Germaniae ("German wars") Pliny the Elder , who had served as an officer in Germania in the middle of the 1st century. The Libri belli Germanici (“Books of the Germanic War”) by the contemporary witness Aufidius Bassus may also have been incorporated. In addition, Tacitus evaluated senate files and other official sources. Tacitus was generally well informed. It is possible that he lived in Cologne for a while and knew the Roman-Germanic border region first-hand.

The first six books of the annals are handed down in a medieval copy from the Fulda monastery , the Codex Medicaeus I = Codex Laurentianus 68.1 . The codex was carefully prepared and should faithfully reproduce its original. Overall, the annals are considered a reliable source. The Tabula Siarensis found in Spain in 1981 - a memorial plaque made of bronze, which was made in 19 AD in honor of Germanicus who died that year and contains a list of his services - confirms and documents the reports on the triumphal procession in 17 AD the downright documentary working method of Tacitus in important points.

Tacitus did not create a war report or a replica of Roman military campaigns, such as those in the foreground in Caesar's De bello Gallico (Gallic War). Rather, it was about drawing people with their feelings and their fates in powerful pictures and dramatic actions. It did not provide all the information necessary to understand the course of the war and assumed that the reader had extensive knowledge of the context. In addition, an enormous literary compression of the text often prevents full certainty in understanding the passage. That is why the interpretation of the military operations is difficult. The depiction of the campaign in the summer of 16 AD is one of the most discussed passages in the annals.

The conflict between Tiberius and Germanicus in Tacitus

The internal political thread of the description is formed by the growing tensions between the popular Germanicus and the unpopular Emperor Tiberius. The sympathies of Tacitus clearly belong to the “young 'hero'”. Nevertheless, Germanicus is not glorified unilaterally. Tacitus also lets Tiberius have his say in detail. The historian must have considered Tiberius 'arguments to be sensible - "Tacitus' head [inclined] to Tiberius and his heart to Germanicus," as the ancient historian Dieter Timpe judged.

Tacitus was influenced by the historiography of the Claudian period (41–54 AD). Emperor Claudius was the brother of Germanicus, and the judgment of the Claudian historians, among them Pliny the Elder, was correspondingly favorable. Ä. There were also parallels to the life of Gnaeus Iulius Agricola, who was worshiped by Tacitus . Agricola was the Roman governor in Britain (77-84 AD) and father-in-law of Tacitus. Under Domitian he had to endure something like Germanicus under Tiberius.

prehistory

Reorganization after the Varus Battle

Germanic associations under the leadership of the Cheruscan prince Arminius had crushed the legions of Publius Quinctilius Varus in the autumn of 9 AD at the Saltus Teutoburgensis (Teutoburg Forest). Three of the five legions stationed on the Rhine had perished. Immediately the Roman emperor Augustus sent his adopted son, the crisis-proven Tiberius, across the Alps to stabilize the situation. Fears that the Germanic peoples might seize the opportunity to invade Gaul or even Italy turned out to be unfounded.

In 10 AD, the two remaining legions were supplemented by six more, although their combat value was initially doubtful. Legions I (Germanica) , V (Alaudae) , XX (Valeria Victrix) and XXI (Rapax) were now on the Lower Rhine, and II (Augusta) , XIII (Gemina) , XIV (Gemina) and XVI (Gallica) on the Upper Rhine . It is uncertain whether Legions I and V were the ones that escaped the disaster the previous year, or the XIII and XIV.

The auxiliaries were also considerably strengthened. Tacitus reports 26 cohorts and eight Alen for the year 14 AD . Overall, the army strength on the Rhine from 10 AD onwards was around 80,000 men. In addition, allied tribes formed warrior groups of unknown size in the event of war.

Measures of Tiberius until 12 AD

For the years 11 and 12 AD, military operations with increasing depth have been handed down. The legionaries rebuilt bases on the right bank of the Rhine, laid limites (wide paths) and created a deserted strip east of the Rhine. Fleet operations on the North Sea ensured the loyalty of the coastal tribes.

Tiberius went to work extremely cautiously: he listened to the proposals of a council of war, as Suetonius reports, and personally checked the loading of the hawser - nothing superfluous should burden the marching columns. The general did not want to be guilty of the negligence of a Varus. In the field, Tiberius led a spartan life, gave all orders in writing, insisted on the strictest discipline and reactivated old punishments. The general renounced risky undertakings, respected feasibility limits and consistently adhered to what Caesar had described as the “rule and custom of the Roman army” (ratio et consuetudo exercitus Romani) .

In AD 12, Tiberius escaped an attempt to kill a Brukterer . The assassin had sneaked into the general's environment, but revealed himself through his behavior. In autumn Tiberius traveled to Rome and celebrated his triumph in Illyria , which had to be postponed in the year 9 AD. The farewell to Germania should be final. Tiberius stayed at the 75-year-old's side as the designated successor to Augustus. Augustus transferred the supreme command (imperium proconsulare) of the largest Roman army of that time to the almost thirty-year-old Germanicus.

Germanicus as commander from 12 AD.

Germanicus was the son of Nero Claudius Drusus (* 38 BC; † 9 BC), who lived in 12 BC. With the Drusus campaigns had heralded the Augustan German Wars and had a fatal accident shortly after reaching the Elbe . In addition, he was the grandson of Augustus (by adopting his father) and the nephew of Tiberius and his adopted son. He had the name "Germanicus" since he was a boy, after Augustus had bestowed this hereditary honor on his father posthumously. According to Augustus' will, Germanicus would later succeed Tiberius as emperor.

Germanicus gained his first military experience in the Pannonian uprising (6 to 9 AD). In the year 9 AD he accompanied Tiberius to Germania and received military "follow-up training" from him. At the end of the year 12, at the latest at the beginning of 13 AD, the power of command passed to Germanicus. Advances across the Rhine this year are likely, but not proven. Apparently no military operations were planned for the year 14 AD, because Germanicus went to Gaul to initiate tax collections. It remains to be seen whether these served to prepare for war.

The appointment of Germanicus as commander-in-chief on the Rhine by Augustus had a “programmatic character”: the name “Germanicus” and the claims behind it; the expectations of the Rhenish legions, who held the memory of Drusus in the highest honor and who hoped for similar general services from the son; the model of Alexander the Great , in whose tradition Germanicus, like his father, seems to have seen himself; the supreme command of the mightiest army of that time; the land whose tribes the father had warred and which now lay on the other bank of the Rhine - all of this demanded of Germanicus "to follow in the footsteps of his father" and underlines the will of the client Augustus, the Roman rule between the Rhine and Elbe restore.

The Mutiny of the Legions AD 14

Augustus died on August 19, 14 AD, Tiberius succeeded him. The legions on the Rhine saw their opportunity to force an end to excessively long hours of service, low wages, excessively harsh discipline, arbitrariness and harassment. A mutiny broke out, the situation escalated, and hated centurions were murdered. The rebels offered the leadership of the empire to the popular Germanicus; with the help of the legions he was supposed to overthrow the unpopular Tiberius from the throne. Germanicus and his legates (commanders) remained loyal, but initially acted not very happy; the evacuation of the Germanicus family failed. Eventually the legions were calmed down. The ringleaders were killed, some of them by the soldiers themselves. In late autumn Germanicus undertook a campaign against the Martians . The campaign was the prelude to the great campaigns that Germanicus was to undertake until the autumn of 16 AD.

Roman war goals and strategies

War aims of Augustus and Germanicus

The primary war goal of Germanicus, commissioned by Augustus, was to restore the state before the Varus catastrophe - this included the reestablishment of Roman supremacy west of the Rhine and the subjugation of the rebellious tribes, securing Gaul from Germanic raids, retaliation for the destruction of the Varus Legions and the recovery of the three legionary eagles lost in the Varus Battle . In addition, the loyalty of the coastal tribes had to be secured: Friesians and Chauken had stayed away from the Arminius uprising, but rule over them (and possibly other smaller coastal tribes) had to be at least maintained, perhaps partly regained.

It is uncertain whether reaching the Elbe was a serious military goal of Germanicus. It is true that the young general practically invoked this goal. He also received his triumphal procession, among other things, because he had triumphed over the tribes between the Rhine and Elbe. But reaching the Elbe was not militarily justified. It is unclear how an advance to the Elbe could have ended the war in favor of the Romans - on the contrary, a confrontation with the Elbe-Germanic tribes would have widened the conflict considerably and probably also drawn the powerful Marcomanni Empire of Marbod into the conflict. The historian Dieter Timpe states that Tacitus describes the role of the Elbe "almost ironically"; the river appears as the "unrealistic geographical symbol of the ambitious sons of the generals". The Tabula Siarensis no longer mentions the Elbe.

The essential means of achieving the goals was the destruction of the livelihoods of the tribes, i.e. the settlement chambers , the fields and, if possible, the livestock. In doing so, Germanicus tied in with the tactics that Caesar had already used against evasive tribes: the destruction of the economic foundations was intended to wear down the tribe and undermine the authority of the tribal leaders hostile to Rome. In order to secure the apron of the Rhine border, the Romans undertook desolation campaigns against the tribes near the Rhine and pushed them back into the interior of Germania. Fast and surprising advances as well as ruthless harshness, also against its own troops, were essential features of the Germanicus operations. Political measures and military operations also aimed to drive wedges into the tribal coalitions and the tribes themselves. After all, the fleet and the use of the waterways also played an important role.

Goals of Tiberius

The comprehensive war aims of Augustus and Germanicus contrasted with the reduced aims of Tiberius. The experienced general and expert on Germania relied on control of the tribal world through diplomacy, money and the exploitation of the notorious aristocratic and tribal conflicts. But first Tiberius had to allow Germanicus, who could refer to the mandate of the late emperor. In the words of Boris Dreyer : "Anyone who wanted to make a correction here had no easy task ahead of them, even after the death of the deified Augustus". Tiberius only managed to establish himself after two years.

Involved Germanic tribes

The Roman attacks were directed primarily against the tribes that were involved in the Varus Battle. However, the coalition grew beyond this circle in the course of the campaigns. According to Tacitus, Germanicus finally held "his triumph over the Cherusci , Chatti and Angrivarians as well as the other tribes that inhabit (the land) as far as the Elbe in 17 AD." According to Strabon, prisoners from subjugated tribes were carried along in the triumphal procession, " namely from the Kaulken, Ampsanern , Brukterern , Usipetern , Cheruskern, Chatten, Chattuariern , Landern and Tubattiern . ”The Martians certainly also belonged to the Arminius coalition, even if they are not listed; their equation with the countries is controversial. Also unnamed clientele of the allies are likely to have taken up arms. For the Cheruscan clientele, for example, the small tribe of the Foser would be considered. In addition, individual followers will have joined Arminius under their own leaders.

The tribes in the extreme northwest of Germany (Frisians, Batavians and others) provided the Romans with auxiliary troops, their participation in the Arminius coalition is excluded. The same applies to the Chauken , even if they possibly sympathized with Arminius, as should indicate during the battle of Idistaviso. The Elbe Germanic tribes and the Marcomanni under Marbod stayed away from the coalition.

Campaign year AD 14

Martian campaign

Immediately after the mutiny ended and at an unusually late hour, Germanicus ordered a campaign against the Martians, who settled between the upper reaches of the Lippe and Ruhr . The sources express themselves differently about the reasons and goals of the military operation: According to Cassius Dio, Germanicus feared new unrest in the army and crossed the Rhine to employ the troops and supply them with booty. Tacitus, on the other hand, reports that the soldiers themselves pushed for the campaign in order to rehabilitate themselves. The reason for the psychological view of Tacitus may have been in his endeavor to uncover the "background of human decisions". Research gives preference to the interpretation of the Dio as a whole.

Germanicus had a ship bridge built over the Rhine and 12,000 men from the four Lower Rhine legions, as well as 8 cavalry units and 26 cohorts of allies. In total, the armed force should have comprised around 30,000 men. The Romans had received news of upcoming cultic celebrations among the Martians and were approaching unnoticed via remote paths. They managed to lock in the celebrants. Four attack wedges caused a slaughter, even children, women and old people were not spared, as Tacitus reports. The legions destroyed the nationally important Tamfana sanctuary . Dio reports rich booty for the soldiers.

March back

On the march back, the Usipeters, Brukterer and Tubanten attacked the army, perhaps in the Heissiwald near Essen or in the area of the central Ruhr. Germanic diversionary maneuvers were aimed at the vanguard and the center of the Roman marching column. The main force eventually attacked the rearguard from wooded hills. The XX. Legion turned, threw itself on the attackers and stabilized the situation. The army reached the Rhine without further incident.

At the end of the year not only was the mutiny of the legions finally settled, but the troops had also gained confidence in the leadership of Germanicus. The campaign "ended with a clear success, in which Germanicus played a significant role."

Campaign year 15 AD

Inner-Cheruscan conflicts

The mutiny of the legions offered Arminius an opportunity to “settle accounts with the enemy within”. The pro-Roman Cheruscan prince Segestes had warned the Roman governor Varus of Arminius's attack plans in 9 AD, but in vain. The hostility of the princely families got an additional personal note when Arminius married his daughter Thusnelda against the will of Segestes , although she was promised to someone else - the “son-in-law was hated, the in-laws were enemies”, as Tacitus sums up. In the autumn / winter of AD 14, Arminius apparently wanted to force a decision. He went against Segestes, but this seemed to have gained the upper hand at first.

The inner-Cheruscan power struggle, in turn, did not remain hidden from Germanicus. He hoped that the Arminius coalition would disintegrate and that Rome-friendly forces would take over the leadership of the tribe. He therefore changed his campaign plans, which had only planned a major campaign for the summer of AD 15, and attacked in the spring. The goal was the Chatten, whose royal houses were related to those of the Cherusci. Presumably a direct Roman intervention in Cheruscan territory would have turned the tribe against the Segestes party.

Chat campaign

In the spring of 15 AD, Germanicus and the Upper Rhine Army invaded the Chattas from Mainz . The march presumably led through the Wetterau to what is now northern Hesse. Possibly the Roman camp Friedberg was on the route. As in the previous autumn, the Romans were able to take advantage of the element of surprise. The unusually dry weather allowed the rapid advance of light troops without special paving of roads and river crossings. Teutons who could not escape were captured or killed. On the Eder , a Chatti contingent tried in vain to prevent the Romans from crossing. Part of the tribe then submitted, another part dispersed into the woods. The Romans destroyed the main town Mattium (cannot be reliably localized) and devastated the settlement areas.

The Cherusci planned to rush to the aid of the Chats. However, this was prevented by the Legate Aulus Caecina Severus , who operated with the Lower Rhine Army further north in the Lippe-Ems region. The Martians dared to attack Caecina, but were defeated "in a happy battle".

On the march back Germanicus received bad news: Segestes was defeated in the power struggle with Arminius and was besieged in his fortified manor. However, he had previously managed to bring the pregnant Thusnelda under his control. Germanicus, who was apparently still deep in Germania, turned and hurried to the aid of the trapped. The legions drove out the besiegers and escorted Segestes with his supporters and prisoners to the Rhine. Later that year, Segimer, Segestes' brother, was also to go into exile in Rome in a similar manner. Thusnelda gave birth to a son in captivity who was named Thumelicus . He was brought up in Ravenna and later fell "to the mockery victim", as Tacitus narrates; Details of this are contained in an annals book that has been lost.

Fleet operation and the Brukterer campaign

Meanwhile, Arminius had succeeded in increasing his force. He was able to win the Cheruscan prince Inguiomerus , an uncle of Arminius and up to now a friend of the Romans, to his side and mobilize neighboring tribes against Rome. Germanicus expressed concern about these developments and again changed his plans for the summer campaign: "So that the war does not break in with all its might", the general now strived to "tear apart the enemy (forces)". He formed three army pillars: Caecina led 40 cohorts with around 20,000 men from Xanten to the Brukterer area between the Rhine and Ems. The Prefect Pedo crossed the Frisian territory in the central and northern Netherlands with his cavalry . Germanicus had around 30,000 men of the four upper Rhine legions by ship via the Flevosee (lat. Lacus Flevo , today's IJsselmeer ) and the North Sea shipping in the Ems. The fleet maneuver not only brought supplies by river transport to the area of operations, but also ensured the loyalty of the coastal peoples. A Chauky troop contingent was incorporated into the army platoon, which amounted to a hostage position. An impressive force finally gathered at a meeting point on the Ems, perhaps near Rheine .

The legions moved up the river through the Brukterer area, but they avoided a fight and left scorched earth for the advancing Romans. A quick unit under Lucius Stertinius managed to get the eagle of the XIX. Legion to ensure. Ultimately, the army was "led into the most remote parts of the Bruktererland and all the area between the Ems and Lippe was devastated, not far from the Teutoburg Forest, in which, it was said, the remains of Varus and his legions were still unburied."

Burial of the Varus Army

Germanicus decided to pay final respects to the remains of the fallen. He may also have intended to investigate the Varus disaster more closely. A vanguard under Caecina explored the “hidden forest ravines” and built dam paths and bridges for the advancing army. The soldiers first discovered the traces of the first legion camp, large enough for three legions. Finally they came to the half-destroyed ramparts and the shallow trenches, in whose protection the decimated remains of the Varus army had taken refuge. Tacitus vividly describes the impressions that came up:

“In the middle of the field (one saw) pale bones, scattered or in a pile, depending on whether the soldiers had fled or resisted. Next to it lay broken weapons and the skeleton of horses, and at the same time one saw human skulls nailed to the tree stumps. In the neighboring groves stood the altars of the barbarians, at which they slaughtered the tribunes and centurions of the first rank. And survivors who escaped this defeat, the battle or the captivity, said that here the legates had fallen, there the eagles were stolen; they showed where the first wound was inflicted on Varus, where he had found death with his own blow through his unfortunate right hand; on what elevation Arminius spoke to the army, how many gallows for the prisoners, what pits of torture there were and how he mocked full of arrogance with the standards and eagles. "

The soldiers buried the bones of their comrades. Germanicus laid the first piece of lawn on the burial mound, according to Tacitus. In the Suetonian tradition, he was the first to collect mortal remains for burial by hand. Tiberius disapproved of the burial because of its demoralizing effect on the legions; In addition, Germanicus held the office of augur and should not have come into contact with corpses for religious reasons.

The Kalkriese site and the Tacite description

The burial described supports the localization of the Varus Battle at the Kalkriese site . Bone pits were discovered there that contain the remains of at least 17 adults between the ages of 20 and 47. Some of the bone parts show significant signs of injury. With the exception of a pelvic bone fragment, the remains were assigned exclusively to male individuals. The skeletal parts were found without anatomical connection and mixed with animal bones. They were only collected and buried after the soft tissues had passed away. The findings can be "associated with a battle."

In summer 2016, the remains of another wall were discovered in Kalkriese. This, together with the wall on the Oberesch, which has been known for a long time, could belong to the last Varus camp mentioned by Tacitus. In 2017 excavations should bring further information [out of date] . As early as 2011, the possibility was considered that the Wall at Oberesch could not have been part of a Germanic ambush, but a Roman camp.

Battle in the summer of AD 15

Arminius meanwhile had withdrawn into impassable terrain, where Germanicus followed. On one level, the Germanic peoples stood up for battle. The Roman cavalry attacked from the march, the warriors fled for pretense. A surprising Germanic flank attack brought the cavalry into disarray and also almost pushed the reserve cohorts that had rushed up into a swamp. Only the advancing legions could stabilize the situation. They "parted without a decision," as Tacitus admitted. Germanicus may have underestimated his opponent because he attributed the catastrophe of 9 AD mainly to a failure of the Varus and did not count on the military capabilities of a Germanic force led by Arminius.

Battle of the Pontes longi

After the battle, Germanicus ordered the return to the winter camp. He himself marched with his army from the Upper Rhine to the Ems to board the ships. The riders should follow along the coast. The four Lower Rhine legions of Caecina took the land route that led them over the pontes longi (long bridges). These Germanic boardwalks , located either in the north German lowlands or between the Rhine and Ems, led through extensive swamp areas and had been expanded by Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus almost two decades earlier . Perhaps Caecina's troops should repair the roads in preparation for the next year of the campaign.

Those responsible were obviously aware of the danger of a Germanic attack on Caecina's army: Germanicus asked the legate to cross the pontes longi "as quickly as possible, although he was returning on familiar routes." Nevertheless, Arminius managed to shorten the legions Because of overtaking. In swampy terrain, he forced the Romans to battle. After two days of heavy fighting and the abandonment of the entourage , the legions were able to set up camp on solid ground on the evening of the second day. In this situation, Arminius advised waiting; he wanted to let the Romans move out the next day and attack again on the march. At the instigation of the Inguiomerus, however, the Germanic peoples attack the camp. A surprise failure by the Romans repulsed the attackers. The victory was so complete that the legions were no longer in danger as they marched on.

Storm surge losses

Meanwhile, parts of the associations led by Germanicus had got into trouble. Two of the four legions were initially unable to board the ships because the vehicles would have run aground if they were fully loaded. Therefore, the Legate Publius Vitellius should lead the II and the XIV Legion along the coast. A severe storm surge on the equinox (September 23 for the year 15 AD) flooded the coastal areas and carried away many of the marchers. The survivors struggled to escape to higher ground. Allegedly on the Weser - parts of the research suspect a traditional error here - the survivors re-established contact with the fleet and embarked.

Conflict with Tiberius

The results of the campaign year were sobering. The Romans had retained control over the North Sea tribes, brought home a Varus eagle and carried out acts of revenge for the Varus defeat. But the hoped-for split between the Cherusci did not materialize and the Germanic resistance was unbroken. In addition, the tribes managed to inflict considerable losses on the Romans. With Arminius, Germanicus had an opponent who, due to his extraordinary skills, had the upper hand in 15 AD.

Tiberus disapproved of his general's conduct of war. Germanicus' approach seemed too risky and lacking in concept. In autumn at the latest, perhaps already in summer, the emperor pushed for an end to the war. The granting of a triumph was the unmistakable signal to Germanicus to end the war. But the young general ignored the demands from Rome and prepared for the next year for a big blow against the Arminius coalition.

Campaign year 16 AD

Fleet strategy

In AD 16, the goal was no longer to split the enemy, but to destroy it. A "bloody and merciless offensive war", marked by ruthless severity against the enemy and one's own troops, reached its climax in 16 AD. The main opponents were the Cherusci, who were to be attacked in their core areas on the upper Weser and in the Leinetal .

Tacitus lets the Germanicus make strategic and tactical considerations in detail: For the Germanic peoples, forests and swamps as well as the short summer, which limited the time of Roman operations, are advantageous; Field battles in open terrain are disadvantageous. For the Romans, on the other hand, the long marches, the consumption of weapons, the long convoy columns and the fact that the Gallic horse resources were meanwhile almost exhausted would be problematic. The sea route offered a solution: legions and provisions could be transported together and campaigns started earlier in the year. The horses were spared by sea and river transport. In addition, there was the element of surprise, because the legions could suddenly advance deep into the interior of Germania via the north German rivers. Tacitus mentions another argument elsewhere: The Teutons had the habit of attacking the Romans on their marches back because the road problems increased as the season progressed due to the weather, the supplies were largely exhausted and the legions could no longer operate flexibly. A fleet improved the logistical possibilities and shortened the marches back.

In order to implement this strategy, Germanicus ordered the equipment of a fleet of 1,000 ships, which Tacitus described in detail: Some (aliae) of the transporters were built short, with a wide hull, but narrow bow and stern to withstand the waves more easily; some (quaedam) had a flat keel in order to be able to run aground; several (plures) were equipped with steering rudders in front and behind, in order to be able to move the vehicle sideways; many (multae) had decks on or under their protection to carry horses, provisions and artillery.

Military operations in the spring

While the ship's hold was being prepared well into the spring, Germanicus ordered military operations against tribes close to the Rhine. The Legate Silius moved against the Chatten with swift troops from Mainz, but only managed to capture the wife and daughter of the Chattenfürst Arpus.

Meanwhile, Germanicus marched up the Lippe with six legions to relieve a fort that was besieged by Teutons. The camp could have been Aliso ; in this case it would have been rebuilt after the Varus disaster and would have been occupied for the winter. The Germanic tribes withdrew from the overwhelming forces, but destroyed the burial mound erected the previous year for the fallen soldiers of the Varus Battle and a Drusus altar. Germanicus had the altar restored and roads and dams between the Rhine and Aliso re-fortified. Then he gathered the legions at the Bataverinsel between the Lower Rhine and Waal in order to board the ships that were now waiting there.

Fleet landing on the Ems

As in the previous year, but now with all eight legions and the cavalry, the association sailed through the Drusus Canal and the Flevo Lake across the North Sea into the Ems. The fleet is believed to have transported around 70,000 men, as well as around 10,000 riding horses and just as many pack animals. The ships landed near the mouth of the river still under the influence of the tides - a contradiction to the strategic concept that emphasized the advantages of river travel. The landing took place on the western bank of the Ems. In Bentumersiel Roman findings have been discovered which can be temporally associated with military operations of Germanicus. Evidence of a camp or fleet landing site has not yet been found.

Tacitus describes the landing as well as the difficulties and delays in the subsequent Ems crossing. This 8th chapter in the second book of the annals is one of the most enigmatic and controversial of the Tacite Germanicus description; final clarity has not yet been achieved. The army's subsequent route also remains uncertain. The way probably led through the areas of the Chauken and Angrivarians and finally up the Weser. A revolt of Angrivarian tribes in the rear of the Romans was quickly suppressed by cavalry and lightly armed men under Stertinius.

First fighting

The Romans probably set up a base on the western bank of the Weser at Porta Westfalica . The Germanic associations had gathered east of the river. Across the river, a dispute broke out between Arminius and his brother Flavus ("The Blonde"), who was in Roman service. Flavus emphasized the greatness of Rome, warned against the punishments for the vanquished and emphasized the leniency for the subjugated; Arminius's wife and son would also be treated well. Arminius reminded his brother of the “sacred obligation towards the fatherland” (fas patriae) , the “freedom inherited from old age ” (libertatem avitam) and the local gods. A dispute broke out, Arminius announced a battle to the Romans.

On the next day, Roman cavalry units crossed the river at fords to secure the army's bridging. The Batavian auxiliaries, led by Chariovalda, were ambushed and nearly wiped out. Chariovalda fell before other Roman units under the legate Stertinius and the primipilar Aemilius could rush to the aid of the afflicted.

The Romans crossed the Weser and learned from a defector the battle site chosen by Arminius. They also received news that other tribes had come together and were planning a night raid on the camp. This reference is considered to be evidence of the massive support of the Cherusci by other Germanic tribes.

Germanic rallying point was a forest that was dedicated to " Hercules " - actually the Donar . From the Tacite account it is not clear how long the Romans were at this point in time east of the Weser. It is also unknown which camp - a marching camp or the base at Porta Westfalica to which the Romans might have returned - was to be the target of the attack. The Teutons recognized that the Romans had been warned and prepared and refrained from the attack. Germanic attempts to persuade the soldiers to desert with the promise of land, money (100 sesterces daily) and women were also unsuccessful .

The battle of Idistaviso

The next morning Germanicus turned to his soldiers and prepared them for a decisive battle in the woods. Not only are the plains favorable for legionnaires, Tacitus ordered the general to explain, but also mountains and forests. The Germanic tribes could hardly handle their large shields and lances in the undergrowth; their unprotected bodies, especially their faces, would be good targets for the compact weapons of the well-armed Romans. The battle brings the soldiers the end of the strenuous marches and sea voyages: "The Elbe is already closer than the Rhine, and beyond that there is no war (anymore)". Finally, he led the army onto the battlefield, a level called Idistaviso ("Idis places meadow"). The confrontation is considered the greatest battle of the Augustan Germanic Wars. The exact location is unknown, the place is generally believed to be between Minden and Rinteln .

The plain stretched irregularly between the Weser and hills and was bordered "at the back" by a light forest, reports Tacitus. The Cherusci had occupied the heights, probably to attack the Romans on the flank. The other tribes had taken up positions on the plain and on the edge of the forest. The Cheruscan advance came too early and Germanicus sent the cavalry against the warriors. Stertinius received the order to lead his units in the rear of the Cherusci. A long drawn-out battle of evasion and persecution developed, the course of which cannot be reconstructed beyond doubt on the basis of the Tacite descriptions. Tacitus reports that the Germanic peoples flee in the opposite direction: Warriors who had occupied the plain fled into the forest, while others were pushed out of the forest into the plain. In the meantime, the Cheruscans had to leave the hills, which they had apparently reoccupied, and, under the leadership of Arminius, threw themselves on the Roman archers on the plain, who, however, rushed to aid from Rhaetian and Gallic auxiliaries. At this point at the latest, the battle should have been decided in favor of the Romans. The wounded Arminius was able to break through the Roman ranks and get to safety; Rumor has it that he was caught by the Chekh auxiliary troops, but let go again.

A large number of (plerusque) Germanic tribes who wanted to swim across the Weser drowned. Others tried to hide in the treetops, but were shot down by archers. The corpses of the fallen warriors covered the ground for ten miles, according to Tacitus. Research considers the description of the losses to be greatly exaggerated, among other things because Arminius was able to lead an army against the mighty Marcomann king Marbod as early as the next year.

Germanicus had a tropaion (victory mark made from prey weapons) built and the defeated tribes (gentes) listed in an inscription . The army proclaimed Tiberius emperor ( imperatorial acclamation ), an honor that he may not have accepted.

Battle of the Angrivarian Wall

The developments following the battle of Idistaviso are only hinted at in Tacitus; the temporal dimensions also remain unclear. At least parts of the Cherusci seem to have initially made preparations to flee across the Elbe. Apparently, however, Arminius succeeded in rallying the Germanic troops and mobilizing further forces: "People and nobles, young men and old men suddenly stormed the Roman army and confused it".

Arminius again offered the Romans a battle at a Germanic long wall , the so-called Angrivarian Wall . The Angrivarians had raised the bulwark as a border fortification against their southern neighbors, the Cherusci. The localization is uncertain; the most likely location is the area between Steinhuder Meer and Stolzenau . In the village of Leese , a wall structure was archaeologically examined in 1926 and identified as an Angrivarian wall. However, this interpretation is controversial.

Tacitus describes the battle, but here, too, the course cannot be clearly understood. The Germanic foot troops had occupied the wall and initially withstood the Roman attack. Only when the Romans used long-range weapons could the defenders be driven out. The hardest fighting then seems to have broken out in the neighboring forests. The Praetorian Guards led the attack on the forests, which also seems to have put the Romans in a threatening position: “The enemy at the rear was blocked by the swamp, the Romans by the river or the mountains; for both of them there was the compulsion to stand firm, hope lay only in bravery, salvation came only from victory. ”Once again the armor and armament of the Romans proved their worth. Germanicus instructed his soldiers not to take any prisoners, because "the destruction of the tribe alone will put an end to the war."

At the end of the day the Romans had claimed the field, but as before with Idistaviso, Germanicus had not achieved the real goal of annihilating the enemy. Nevertheless, the soldiers erected a tropaion of captured weapons with a, according to Tacitus, "proud" (superbo) inscription: "After the defeat of the tribes between the Rhine and Elbe, the army of Emperor Tiberius consecrated this monument to (...) Augustus." The dedication in no way corresponded to political and military facts.

Subsequently, Stertinius was sent again against the aggressors and was able to accept their unconditional submission without a fight. The tribe then received “full forgiveness”.

Way back and fleet disaster

After that, Germanicus ended the campaign because "it was now midsummer" - an astonishing reason given the pressure of time and success that Germanicus was under. Some legions returned by land, the majority embarked on the Ems.

On the North Sea, the fleet got caught in a severe storm, which Tacitus vividly described. Some (pars) of the ships sank , even more (plures) stranded on uninhabited islands; the shipwrecked had to feed on horse carcasses until they were rescued. The Germanicus' galley landed at the Chauken. After the weather improved, the mended ships returned, some without oars, with emergency sails and in tow. Legionnaires who had been captured by distant coastal tribes were ransomed by the Angrivarians on behalf of the Romans. Some soldiers had been sent as far as Britain and were sent back by the petty kings.

Autumn campaigns

Returning to the Rhine, Germanicus ordered further military operations. Silius marched against the Chatten with 30,000 foot soldiers and 3,000 horsemen, but could not face the enemy and contented himself with devastation. Germanicus led his legions into the Martian area. The Martian leader (dux) Mallovendus told the Romans that one of the Varus eagles was buried in a grove. A raiding party succeeded in recovering the standard. What followed was a desolation train that met with little resistance.

At this point in the annals, Tacitus showed how critical he was of the subsequent termination of the Germanic Wars by Tiberius: The Germanic peoples would never have felt such fear of the Romans as they did in the autumn of 16 AD. The legions appeared invincible because they were after the losses of the naval journey were still able to undertake incursions into Germania with determination and great manpower. The soldiers returned to the winter camp in good spirits, "because the happy campaign had compensated them for the misfortune on the sea." There was no doubt that the Teutons would have submitted in the next summer.

End of the war and recall of Germanicus

Tiberius did not share the optimism of Germanicus handed down by Tacitus and was now determined to end the campaigns. The experienced general and expert on Germania had to fear that the war "in view of G [ermanicus'] almost obsessed bravado always harbored the danger of a second Varus catastrophe." Tiberius was in his third year of reign at the end of AD 16 and was now able to face the test of strength with his popular adopted son. In numerous letters, according to Tacitus, the Emperor criticized: There had been enough successes (eventuum) and accidents (casuum) ; At the time, Tiberius himself, as Commander-in-Chief in Germania, achieved more through deliberation (consilio) than through force (vi) . The vengeance for the Varus army was enough, the tribes could now be left to their internal disputes (internis discordiis) . In addition, the command on the Rhine should pass to his biological son Drusus , so that he would have opportunities to earn fame.

The highest honors (which, however, had already been awarded to Germanicus and his legates in AD 15) and a second consulate were supposed to maintain the form and make it easier for Germanicus to return. Germanicus finally had to bow to the growing pressure of Tiberius. He left Germania to celebrate the triumph that had already been awarded the previous year in Rome and then to take on a task in the east of the empire. The Germanicus campaigns and with them the era of the Augustan German Wars were over.

Balance sheet and consequences of the Germanicus campaigns

Roman balance sheet

The successes of the Germanicus include at least two major battle victories (Idistaviso and Angrivarian Wall), the bringing home of two Varus eagles, captures (including the pregnant wife of Arminius), the burial of the Varus army, the displacement of the tribes near the Rhine into the interior, and devastation trains and Revenge measures. Control over the coastal tribes was retained or regained, the Angrivarians and individual tribal chiefs were subjugated. On the other hand, there are enormous losses. The historian Reinhard Wolters assumes that almost as many soldiers fell under Germanicus as in the entire Germanic Wars since 12 BC. Including the Varus catastrophe; Peter Kehne estimates the losses at 20,000 to 25,000 men.

Germanicus was far from his ambitious goal - should it actually have existed in this form - of extending Roman control to the Elbe. Historical research assesses the chances of victory for the year 17 AD largely negatively. The Roman military strikes had not decisively weakened the Germanic peoples, rather the Germanic resistance seems to have grown with the intensity of the attack by the Romans. The size and tenacity of the Arminius coalition had finally forced the attempt at conquest to be abandoned. Germanicus's war of annihilation had failed.

For the Romans, the recall of Germanicus meant the end of the military offensive policy. The troop masses in Xanten and Mainz were reduced, the unified high command over the Rhine Army ended. The locations on the right bank of the Rhine were abandoned with the exception of a few places on the North Sea coast and in front of Mainz. Influence on the tribal world was continued, but by other means: diplomacy, money and contacts with old allies (for example the Ampsivarian prince and Arminius opponent Boiocalus) were intended to maintain the Roman influence east of the Rhine.

Subsequent reinterpretation of the war aims by Tiberius

Germanicus celebrated his triumph in Rome on May 26, 17 AD. Thusnelda with her two-year-old son and other prisoners from tribes named by Strabo were carried on the train. A triumphal arch was consecrated next to the Temple of Saturn to recover the Varus eagle . The triumph should hide how little Germanicus had actually achieved. It was “the fiction that he had succeeded in mastering the entire West Germanic tribes”. For Tacitus, the honors were a farce, because they were less about rewarding successes, but rather concealing failures and ending the war: "The war was accepted as really ended because Germanicus had been prevented from ending (prohibitus) (pro confecto accipiebatur). . "

The inscription on Tabula Siarensis turned out to be far more realistic than the reason for triumph two years later . There is no word about the Elbe, no tribes and no battles are named. There is only talk of the victory over the Teutons, of their driving back from the Gallic border, of the recovery of the eagles and of revenge for the Varus defeat. The merits listed no longer corresponded to the ambitious plans of Augustus and Germanicus, rather the limited aim of Tiberius emerges here. The emperor used the honor of the dead to later explain his own conception as a common goal. This reinterpretation found its expression in the annals: The war against the Germanic peoples had been waged “more to eradicate the shame [of the Varus catastrophe] (…) than out of an effort to expand the empire, or because of the prospect of corresponding Profit. "

"... without a doubt the liberator of Germania"

The removal of the Roman threat offered the tribes the opportunity to return to Germanic power politics. As early as 17 AD Arminius was able to successfully attack the kingdom of the Marcomanni king Marbod in Bohemia. Four years later, however, Arminius fell victim to the Cheruscan aristocracy and faction conflicts: The Cheruscan prince's own relatives poisoned the Cheruscan prince, probably also to prevent the reign of kingship in the tribe.

Research estimates the achievement of Arminius in the years 15 and 16 AD as decisive. The Germanic peoples' success came about through the “outstanding strategic skill of Arminius”. The creation of a grand coalition and warfare without the surprise element of the year 9 AD “prove the Cheruscan prince to be a really important politician and general of the Germanic tribes.” The Varus Battle in 9 AD was not the historic turning point in the Confrontation between Romans and Teutons, but rather the period of probation in the years that followed with the climax of the Germanicus campaigns.

This interpretation is in line with Tacitus' assessment. Aware of the final renunciation of Germania by Domitian (emperor until 96 AD), the historian wrote about 100 years after the events of Arminius: “He was without a doubt the liberator of Germania, who, like other kings and military leaders, did not conquer the Roman people its beginnings, but challenged an empire in its full bloom and (had fought) in battles with varying success, but (had remained) undefeated in war. "

Research problems

The fleet landing in the summer of 16 AD.

The depiction of the landing of the fleet at the mouth of the Ems in the summer of 16 AD is one of the most enigmatic passages in the description of the Tacite campaign. So far it could not be explained without text manipulation or elaborate interpretations. First, Tacitus reports on the Germanicus' fleet trip from the Lower Rhine through the Flevo and the North Sea. Then it says: “In the left course of the Ems he left the fleet behind and thereby made a mistake because he did not let them go upstream: he had the army that was to go into the areas on the right crossed; too many days were lost building bridges. "

When landing in the “left course” (laevo amne) of the Ems, it is not entirely certain whether “left” is meant from a geographical point of view (looking from the source to the mouth) or from the perspective of the actor (from the point of view of the Ems entering Germanicus). Evidence for both variants can be found in Tacitus and Pliny. Karl Meister campaigned in 1955 to see the side from the approaching Germanicus. However, this would mean that the Romans would then have crossed the river to the west, which appears militarily pointless. Overall, research gives preference to the geographical perspective, i.e. sees a landing on the west bank and a subsequent crossing in an easterly direction. However, it is unclear whether the Latin amne actually refers to the banks of the Ems or a second branch of the river that has silted up today. Master suggests “arm of the Ems”.

The river crossing causes further interpretation difficulties. In the text of the Codex mediceus , “let drive” (subvexit) and “translate” (transposuit) stand next to each other without punctuation marks (… non subvexit transposuit militem…) . Parts of the research therefore suspect either a subsequent addition of transposuit or the omission of the connective word “and” between the two terms. More recent research rejects such corrections and sees in transposuit the beginning of a new sentence in which the verb is emphasized at the beginning. Many modern translations add a colon to separate them. However, this does not clarify the question of why Germanicus did not allow the fleet to enter the right (eastern) arm of the river or land on the east bank, and why the ships did not continue upstream, as described in the strategic preliminary considerations. According to Strabo, the Ems was navigable. Karl Meister suspects the loaded ships run aground or a danger from driftwood islands. The Romans may also have underestimated the difficulties of building bridges in the tidal area of the river.

Ems-Weser discussion

The question of whether Germanicus actually landed on the Ems (Amisia) in AD 16, as described in Tacitus , or not actually on the Weser (Visurgis) was much discussed . The main area of operation of the Romans, the Cherusker area, was on the middle and upper Weser and on the Leine - an entrance into the Weser would have been obvious. In addition, there is no evidence of a march from the Ems to the Weser in Tacitus. This gap in the description is interpreted in different ways: as a prime example of the typical Tacite brevity (Brevitas), as a loss of text in the tradition or as an error of Tacitus, who may have underestimated the distance from the mouth of the Ems to Porta Westfalica (around 200 km).

Around 1900 Hans Delbrück vehemently advocated the thesis of the Weser entrance. According to him, "the whole purpose of the sea expedition" was "to bring a floating food magazine on the Weser", as he wrote in 1921. This position was taken up again and again. Reinhard Wolters pleaded in 2008 for a conjecture from “Ems” to “Weser”, among other things because Tacitus reports that the attackers rose up behind the army. The Angrivarian core area was then north of the Minden region. The aforementioned elevation "in the back" was only possible on a Roman train up the Weser. Wolters considers it unlikely that Tacitus confused the rivers. Rather, a copyist of the annals text probably wanted to synchronize the place where the army was picked up in late summer 16 AD with the place where it landed and therefore changed the Weser to Ems.

Other researchers consider a conjecture to be unfounded. Erich Koestermann sees a Roman flotilla on the Hase , an eastern tributary of the Ems, as a floating supply base for the advance towards Minden and rules out a trip to the Weser. Dieter Timpe sees no reason to assume that the text has been lost and considers a text change to be unacceptable.

Missing archaeological evidence for the Germanicus campaigns

Archeologically, the military operations of the years 10 to 16 AD are hardly tangible. There is an astonishing lack of finds in view of the extensive operations of the great Tiberius and Germanicus armies.

None of the coin finds on the right bank of the Rhine can be assigned unequivocally to the army of Germanicus. The lack of coins from the Germanicus period can possibly be traced back to the fact that the soldiers were paid mainly with old money. Freshly minted coins reached the troops only irregularly and with a delay. It also happened again and again that no new coins were minted for several years. Loss of coins from the Germanicus campaigns could therefore not be distinguished from those from previous campaigns.

Archaeological sites are also hardly necessarily associated with Germanicus. The bone pits discovered at the Kalkriese site may be traced back to the work of the Germanicus army. Militaria from the Germanicus period were discovered near Bentumersiel near the mouth of the Ems, but no remains that would suggest military installations. The location of the Chatti capital Mattium, conquered by Germanicus, with the Altenburg near Niedenstein is uncertain, as is that of the Angrivarian Wall near Leese. It is possible that the Roman camp near Friedberg (Hessen) belongs to the Germanicus phase. However, it is not to be equated with the camp in Taunus mentioned by Tacitus . The Roman city near Lahnau-Waldgirmes (founded no later than 3 BC) was destroyed in 9 or 14 AD. After this, however, the Romans continued to use the place. The final abandonment of the square is likely to be dated to the year 16 AD, i.e. the Germanicus period. In the Roman main camp Haltern an der Lippe, indications of a use after destruction were found, which are, however, controversial. If the holder is actually dealing with the traditional Aliso, an occupancy up to AD 16 would be assumed , although the numismatic (coinage) findings only go up to AD 9. Otherwise none of the numerous Roman camps discovered in recent decades seem to have survived AD 9.

swell

Sources on the Germanicus campaigns

- Cassius Dio , Historia Romana , Book 54, 33, 3-4; Book 56, 18; 24, 6; 25, 2-3; Book 57, 6, 1; 18, 1

- Ovid , Tristia 3, 12, 45-48; 4, 2, 1-2; 37-46

- Strabon , Geographica 7, 1, 3-4

- Suetonius , Gaius , 3, 2

- Suetonius, Divus Tiberius 18-20

- Tabula Siarensis , Fragment I, lines 12-15

- Tacitus , Annales Book 1, 3, 5-6; 1, 31, 1-3; 1, 49-51; 55-72; Book 2, 5-26; 41; 88, 2; Book 13, 55, 1

- Velleius Paterculus , Historia Romana 2, 120-121; 122, 2

Source edition

- Erich Heller: Tacitus Annals. Translated and explained by Erich Heller (1982). Monolingual edition Munich 1991.

- Hans-Werner Goetz , Karl-Wilhelm Welwei : Old Germania. Excerpts from ancient sources about the Germanic peoples and their relationship to the Roman Empire. Part 2 (= selected sources on the German history of the Middle Ages. Vol. 1a), Darmstadt 1995.

literature

Monographs

- Armin Becker : Rome and the chat. Darmstadt 1992.

- Karl Christ : Drusus and Germanicus. The entry of the Romans into Germania. Paderborn 1959.

- Boris Dreyer : Arminius and the fall of the Varus. Why the Teutons did not become Romans. Stuttgart 2009.

- Boris Dreyer: Places of the Varus catastrophe and the Roman occupation in Germania. The historical-archaeological guide. Darmstadt 2014.

- Klaus-Peter Johne : The Romans on the Elbe. The Elbe river basin in the geographical view of the world and in the political consciousness of Greco-Roman antiquity. Berlin 2006.

- Friedrich Knoke : The war campaigns of Germanicus in Germany. Berlin, 2nd, redesigned several times. Edition 1922.

- Klaus Tausend: Inside Germania. Relations between the Germanic tribes from the 1st century BC BC to the 2nd century AD (= Geographica Historica. Vol. 25). Stuttgart 2009.

- Dieter Timpe : The triumph of Germanicus. Investigations into the campaigns of the years 14-16 AD. in Germania. Bonn 1968.

- Reinhard Wolters : Die Römer in Germanien (= Beck'sche Reihe. Vol. 2136), 6th revised and updated edition. Munich 2011.

- Reinhard Wolters: The battle in the Teutoburg Forest. Arminius, Varus and Roman Germania. 1st, revised, updated and expanded edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-69995-5 (original edition: Munich 2008; 2nd revised edition: Munich 2009).

Articles and RGA contributions

- Peter Kehne : Germanicus. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd edition, Volume 11, 1998, pp. 438-448.

- Karl Meister : The report of Tacitus about the landing of the Germanicus in the mouth of the Ems. In: Hermes , Volume 83, Issue 1, 1955, pp. 92-106.

- Carl Schuchhardt et al .: The Angrivarian-Cheruscan border wall and the two battles of 16 AD between Arminius and Germanicus. In: Prehistorische Zeitschrift 17, 1926, pp. 100-131.

- Kurt Telschow: The recall of Germanicus (16 AD). An example of the continuity of the Roman politics of Germania from Augustus to Tiberius. In: Eckard Lefèvre (Ed.): Monumentum Chiloniense. Studies in the Augustan period. Festschrift Erich Burck. Amsterdam 1975, pp. 148-182.

- Dieter Timpe: Historically. In: Heinrich Beck et al. (Ed.): Germanen, Germania, Germanic antiquity (= RGA, study edition "The Germanen"). Berlin 1998, pp. 2-65.

- Dieter Timpe: Roman geostrategy in Germania during the occupation period. In: Johann-Sebastian Kühlborn et al. (Ed.): Rome on the way to Germania. Geostrategy, roads of advance and logistics. International colloquium in Delbrück-Anreppen from November 4th to 6th, 2004 (= Soil antiquities of Westphalia 45). Mainz 2008, pp. 199-236.

- Reinhard Wolters: Integrum equitem equosque… media in Germania fore: Strategy and course of the Germanicus campaign in AD 16. In: Johann-Sebastian Kühlborn et al. (Ed.): Rome on the way to Germania. Geostrategy, roads of advance and logistics. International colloquium in Delbrück-Anreppen from November 4th to 6th, 2004 (= Soil antiquities of Westphalia 45). Mainz 2008, pp. 237-251.

Anthologies

- Rudolf Aßkamp, Kai Jansen (ed.): Triumph without victory. Rome's end in Germania. Zabern, Darmstadt 2017.

- Stefan Burmeister, Joseph Rottmann (Ed.): I, Germanicus! General priest superstar. (= Archeology in Germany, special issue 08/2015). Theiss, Darmstadt 2015.

- Bruno Krüger (ed.): The Germanic peoples. Volume 1. Berlin 1978

- Johann-Sebastian Kühlborn et al. (Ed.): Rome on the way to Germania. Geostrategy, roads of advance and logistics. International colloquium in Delbrück-Anreppen from November 4th to 6th, 2004 (= Soil antiquities of Westphalia 45). Mainz 2008

- Gustav Adolf Lehmann , Rainer Wiegels (eds.): "Over the Alps and over the Rhine ...". Contributions to the beginnings and the course of the Roman expansion into Central Europe. Berlin 2015.

- Dieter Timpe: Roman-Germanic encounter in the late republic and early imperial era: requirements - confrontations - effects. Collected Studies (Contributions to Antiquity, Volume 233).

Remarks

- ^ Cassius Dio, Historia Romana 57, 18, 1.

- ↑ a b Strabon Geographica 7, 1, 3.

- ↑ Dieter Timpe: The Triumph of Germanicus. Investigations into the campaigns of 14-16 AD in Germania. Bonn 1968, p. 14 f.

- ↑ Dieter Timpe: The Triumph of Germanicus. Investigations into the campaigns of 14-16 AD in Germania. Bonn 1968, p. 21.

- ^ A b c Reinhard Wolters: Integrum equitem equosque… media in Germania fore: Strategy and course of the Germanicus campaign in the year 16 AD. In: Johann-Sebastian Kühlborn et al. (Ed.): Rome on the way to Germania. Geostrategy, roads of advance and logistics. International colloquium in Delbrück-Anreppen from November 4th to 6th, 2004 (= Soil antiquities of Westphalia. Volume 45). Mainz 2008, pp. 237-251, here p. 237.

- ↑ a b Boris Dreyer: Places of the Varus catastrophe and the Roman occupation in Germania. The historical-archaeological guide. Darmstadt 2014, p. 81.

- ↑ Franz Römer : Critical problem and research report on the transmission of the Taciteic writings. In: Wolfgang Haase et al. (Ed.): Rise and decline of the Roman world . Row II: Prinzipat, Volume 33.3. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1991, ISBN 3-11-012541-2 , pp. 2299-2339, here 2302 ff.

- ↑ Cf. Dieter Timpe: The Triumph of Germanicus. Investigations into the campaigns of 14-16 AD in Germania. Bonn 1968, p. 2 f.

- ↑ Reinhard Wolters: The battle in the Teutoburg Forest. Arminius, Varus and Roman Germania. 2nd revised edition. Munich 2009, p. 134. On the Tabula Siarensis as a testimony to the Germanicus campaigns: Boris Dreyer: Arminius and the fall of the Varus. Why the Teutons did not become Romans. Stuttgart 2009, pp. 151-156.

- ^ A b Karl Meister: The report of Tacitus on the landing of Germanicus in the mouth of the Ems. In: Hermes, Volume 83, Issue 1, 1955, pp. 92-106, here p. 106.

- ↑ Erich Koestermann: The campaigns of Germanicus 14-16 AD In: Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte . Vol. 6, 1957, H. 4, pp. 429-479, here p. 430; Boris Dreyer: Arminius and the fall of the Varus. Why the Teutons did not become Romans. Stuttgart 2009, p. 164.

- ↑ Dieter Timpe: The Triumph of Germanicus. Investigations into the campaigns of 14-16 AD in Germania. Bonn 1968, p. 67.

- ↑ a b Dieter Timpe: The Triumph of Germanicus. Investigations into the campaigns of 14-16 AD in Germania. Bonn 1968, p. 77.

- ↑ Boris Dreyer: Places of the Varus catastrophe and the Roman occupation in Germania. The historical-archaeological guide. Darmstadt 2014, p. 82.

- ↑ a b Klaus-Peter Johne: The Romans on the Elbe. The Elbe river basin in the geographical view of the world and in the political consciousness of Greco-Roman antiquity. Berlin 2006, p. 184.

- ^ Armin Becker: Rome and the chat. Darmstadt 1992, p. 187.

- ^ Tacitus: Annales. 1, 49.

- ↑ Reinhard Wolters: Revenge, claim and renunciation. The Roman politics of Germania after the Varus catastrophe. In: LWL-Römermuseum in Haltern am See (ed.): 2000 years of the Varus Battle - Imperium. Stuttgart 2009, pp. 210–216, here p. 210.

- ^ Suetonius Divus Tiberius 18, 1.

- ^ Suetonius Divus Tiberius 19.

- ↑ Caesar De bello Gallico 6, 34, 6; Translation after Marieluise Deißmann: Gaius Julius Caesar. De bello Gallico. The Gallic War. Supplemented edition 2015, p. 351.

- ↑ Dieter Timpe: Roman geostrategy in Germania of the occupation time. In: Johann-Sebastian Kühlborn et al. (Ed.): Rome on the way to Germania. Geostrategy, roads of advance and logistics. International colloquium in Delbrück-Anreppen from November 4th to 6th, 2004 (= Soil antiquities of Westphalia. Volume 45). Mainz 2008, pp. 199-236, here p. 205.

- ^ Suetonius Divus Tiberius 19.

- ↑ Peter Kehne: Germanicus. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd edition, Volume 11, 1998, p. 439.

- ↑ Dieter Timpe: The Triumph of Germanicus. Investigations into the campaigns of 14-16 AD in Germania. Bonn 1968, p. 36 f.

- ↑ Dieter Timpe: The Triumph of Germanicus. Investigations into the campaigns of 14-16 AD in Germania. Bonn 1968, p. 38.

- ^ A b Reinhard Wolters: The battle in the Teutoburg Forest. Arminius, Varus and Roman Germania. 2nd revised edition. Munich 2009, p. 135.

- ↑ Reinhard Wolters: The chats between Rome and the Germanic tribes. From Varus to Domitianus. In: Helmuth Schneider (ed.): Hostile neighbors. Rome and the Teutons. Cologne 2008, pp. 77–96, here p. 81.

- ↑ In detail on the role model function of Alexander the great: Boris Dreyer: Arminius und der Untergang des Varus. Why the Teutons did not become Romans. Stuttgart 2009, pp. 70-73.

- ↑ Dieter Timpe: Roman geostrategy in Germania of the occupation time. In: Johann-Sebastian Kühlborn et al. (Ed.): Rome on the way to Germania. Geostrategy, roads of advance and logistics. International colloquium in Delbrück-Anreppen from November 4th to 6th, 2004 (= Soil antiquities of Westphalia. Volume 45). Mainz 2008, pp. 199–236, here p. 228.

- ↑ Sources: Various passages in Tacitus: Annales. 1 and 2, Strabon Geographica 7, 1, 4; Velleius Paterculus: Historia Romana. 2, 120, 2; 122, 2; Tabula Siarensis Frg. I lines 12-15. Literature selection: Armin Becker: Rom und die Chatten. Darmstadt 1992, p. 217; Klaus-Peter Johne: The Romans on the Elbe. The Elbe river basin in the geographical view of the world and in the political consciousness of Greco-Roman antiquity. Berlin 2006, p. 195; Reinhard Wolters: revenge, claim and renunciation. The Roman politics of Germania after the Varus catastrophe. In: LWL-Römermuseum in Haltern am See (ed.): 2000 years of the Varus Battle - Imperium. Stuttgart 2009, pp. 210–216, here p. 212.

- ↑ Source: Tabula Siarensis Frg. I lines 12-15; see. also Klaus-Peter Johne: The Romans on the Elbe. The Elbe river basin in the geographical view of the world and in the political consciousness of Greco-Roman antiquity. Berlin 2006, p. 195 and Reinhard Wolters: Revenge, claim and renunciation. The Roman politics of Germania after the Varus catastrophe. In: LWL-Römermuseum in Haltern am See (ed.): 2000 years of the Varus Battle - Imperium. Stuttgart 2009, pp. 210–216, here p. 212. Germanicus was actually able to secure two of the eagles.

- ↑ Cf. Armin Becker: Rome and the chats. Darmstadt 1992, p. 214 and Peter Kehne: Germanicus. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd edition, Volume 11, 1998, p. 444.

- ↑ Basic general discussion of the Elbe goal in the Augustan period with Jürgen Deininger: Germaniam pacare. To the more recent discussion about the strategy of Augustus against Germania. In: Chiron . Vol. 30, 2000, pp. 749-773, here pp. 751-757.

- ↑ a b Tacitus: Annales. 2, 14, 4.

- ^ Tacitus: Annales. 2, 41, 2.

- ↑ Dieter Timpe: Roman geostrategy in Germania of the occupation time. In: Johann-Sebastian Kühlborn et al. (Ed.): Rome on the way to Germania. Geostrategy, roads of advance and logistics. International colloquium in Delbrück-Anreppen from November 4th to 6th, 2004 (= Soil antiquities of Westphalia. Volume 45). Mainz 2008, pp. 199–236, here p. 224.

- ↑ Dieter Timpe: Roman geostrategy in Germania of the occupation time. In: Johann-Sebastian Kühlborn et al. (Ed.): Rome on the way to Germania. Geostrategy, roads of advance and logistics. International colloquium in Delbrück-Anreppen from November 4th to 6th, 2004 (= Soil antiquities of Westphalia. Volume 45). Mainz 2008, pp. 199–236, here p. 222.

- ↑ Dieter Timpe: Roman geostrategy in Germania of the occupation time. In: Johann-Sebastian Kühlborn et al. (Ed.): Rome on the way to Germania. Geostrategy, roads of advance and logistics. International colloquium in Delbrück-Anreppen from November 4th to 6th, 2004 (= Soil antiquities of Westphalia. Volume 45). Mainz 2008, pp. 199–236, here p. 207.

- ↑ Johannes Heinrichs: Migrations versus Genocide. Local associations in the northern Gaulle region under Roman conditions. In: Gustav Adolf Lehmann, Rainer Wiegels (ed.): "Over the Alps and over the Rhine ...". Contributions to the beginnings and the course of the Roman expansion into Central Europe. Berlin 2015, pp. 133–163, here p. 156.

-

↑ Peter Kehne: Germanicus. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd edition, Volume 11, 1998, p. 444.

Reinhard Wolters: Revenge, claim and renunciation. The Roman politics of Germania after the Varus catastrophe. In: LWL-Römermuseum in Haltern am See (ed.): 2000 years of the Varus Battle - Imperium. Stuttgart 2009, pp. 210–216, here p. 212. - ↑ a b Reinhard Wolters: Revenge, claim and renunciation. The Roman politics of Germania after the Varus catastrophe. In: LWL-Römermuseum in Haltern am See (ed.): 2000 years of the Varus Battle - Imperium. Stuttgart 2009, pp. 210–216, here p. 211.

- ↑ a b Boris Dreyer: Places of the Varus catastrophe and the Roman occupation in Germania. The historical-archaeological guide. Darmstadt 2014, p. 83.

- ↑ Boris Dreyer: Places of the Varus catastrophe and the Roman occupation in Germania. The historical-archaeological guide. Darmstadt 2014, p. 84. See also Reinhard Wolters: “Tam diu Germania vincitur”. Roman German victories and German victory propaganda up to the end of the 1st century AD (= small notebooks of the coin collection at the Ruhr University in Bochum. No. 10/11). Bochum 1989, p. 40 f.

- ↑ Klaus Tausend: Inside Germania. Relations between the Germanic tribes from the 1st century BC BC to the 2nd century AD (= Geographica Historica. Volume 25). Stuttgart 2009, p. 49.

- ^ Tacitus: Annales. 2, 41, 2.

- ^ Strabon Geographica 7, 1, 4, translation by Hans-Werner Goetz, Karl-Wilhelm Welwei: Altes Germanien. Excerpts from the ancient sources about the Germanic peoples and their relations to the Roman Empire , part 1 (= selected sources on the German history of the Middle Ages. Volume 1a). Darmstadt 1995, p. 95.

- ↑ Klaus-Peter Johne: The Romans on the Elbe. The Elbe river basin in the geographical view of the world and in the political consciousness of Greco-Roman antiquity. Berlin 2006, p. 193.

- ↑ cf. Strabon Geographica 7, 1, 4.

- ^ Heiko Steuer: Troop strengths. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd edition, Volume 29, 2005, pp. 274-283, p. 280.

- ↑ a b Klaus Tausend: Inside Germania. Relations between the Germanic tribes from the 1st century BC BC to the 2nd century AD (= Geographica Historica. Volume 25). Stuttgart 2009, p. 26.

- ^ A b Cassius Dio, Historia Romana 57, 6, 1.

- ↑ a b Tacitus: Annales. 1, 49, 3.

- ↑ a b Dieter Timpe: The Triumph of Germanicus. Investigations into the campaigns of the years 14-16 AD. in Germania. Bonn 1968, p. 29.

- ^ Tacitus: Annales. 1, 51, 1.

- ^ A b Reinhard Wolters: The battle in the Teutoburg Forest. Arminius, Varus and Roman Germania. Munich, 2nd complete Edition 2009, p. 129.

- ↑ cf. Tacitus: Annales. 1, 51, 4.

- ↑ Erich Koestermann: Die Feldzüge des Germanicus 14-16 AD. In: Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, Vol. 6, H. 4, 1957, pp. 429–479, here p. 433.

- ↑ Dieter Timpe: The Triumph of Germanicus. Investigations into the campaigns of the years 14-16 AD. in Germania. Bonn 1968, p. 69.

- ^ Tacitus: Annales. 1, 55, 3.

- ↑ Dieter Timpe: The Triumph of Germanicus. Investigations into the campaigns of the years 14-16 AD. in Germania. Bonn 1968, p. 68 f.

- ^ Tacitus: Annales. 1, 55, 1.

- ^ Armin Becker: Rome and the chat. Darmstadt 1992, p. 197, note 56.

- ^ Tacitus: Annales. 1, 56, 5, translation after Hans-Werner Goetz, Karl-Wilhelm Welwei: Altes Germanien. Excerpts from the ancient sources about the Germanic peoples and their relations to the Roman Empire , part 2 (= selected sources on the German history of the Middle Ages, vol. 1a). Darmstadt 1995, p. 81.

- ^ Heiko Steuer: Landscape organization, settlement network and village structure in Germania in the decades around the birth of Christ. In: Gustav Adolf Lehmann, Rainer Wiegels (Ed.): "Over the Alps and over the Rhine ...". Contributions to the beginnings and the course of the Roman expansion into Central Europe . Berlin 2015, pp. 339–374, here p. 343.

- ↑ Otherwise the Caecina operating in the Lippe-Ems region would have had the shorter way to Segestes. Cf. Armin Becker: Rome and the chats. Darmstadt 1992, p. 200.

- ↑ faction leaders had numerous clients who cannot be equated with followers; Reinhard Wenskus et al .: Cherusker. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. (RGA), 2nd edition, Volume 4, 1978, 430-435, pp. 432 f.

- ^ Tacitus: Annales. 1, 71, 1.

- ^ Tacitus: Annales. 1, 58, 6, translation by Hans-Werner Goetz, Karl-Wilhelm Welwei: Altes Germanien. Excerpts from the ancient sources on the Germanic peoples and their relationship to the Roman Empire , part 2 (= selected sources on German history in the Middle Ages, vol. 1a). Darmstadt 1995, p. 83.

-

↑ Cf. Dieter Timpe: The Triumph of Germanicus. Investigations into the campaigns of the years 14-16 AD. in Germania. Bonn 1968, p. 72 f. and

Klaus-Peter Johne: The Romans on the Elbe. The Elbe river basin in the geographical view of the world and in the political consciousness of Greco-Roman antiquity. Berlin 2006, p. 185. - ^ Tacitus: Annales. 1, 60, 2, translation by Hans-Werner Goetz, Karl-Wilhelm Welwei: Altes Germanien. Excerpts from ancient sources about the Germanic peoples and their relationship to the Roman Empire. Part 2 (= selected sources on German medieval history, vol. 1a). Darmstadt 1995, p. 85.

- ↑ probably not auxiliary, but legionary cohorts; Armin Becker: Rome and the chat. Darmstadt 1992, p. 188.

- ↑ cf. Peter Kehne: On the strategy and logistics of Roman advances into Germania: The Tiberius campaigns of the years 4 and 5 AD. In: Johann-Sebastian Kühlborn et al. (Ed.): Rome on the way to Germania. Geostrategy, roads of advance and logistics . International colloquium in Delbrück-Anreppen from November 4th to 6th, 2004 (= Soil antiquities of Westphalia 45). Mainz 2008, pp. 253-302, here pp. 272 f.

- ↑ Peter Kehne: Germanicus . In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd edition, Volume 11, 1998, p. 442.

- ↑ Hans Viereck: The Roman fleet. Classis romana . Hamburg edition 1996, p. 227.

- ^ Tacitus: Annales. 1, 60, 3, translation Erich Heller: Tacitus Annalen. Translated and explained by Erich Heller (1982). Monolingual edition Munich 1991, p. 66.

- ^ Tacitus: Annales. 1, 61, 1, translation by Hans-Werner Goetz, Karl-Wilhelm Welwei: Old Germania. Excerpts from the ancient sources about the Germanic peoples and their relations to the Roman Empire , part 2 (= selected sources on the German history of the Middle Ages, vol. 1a). Darmstadt 1995, pp. 85-87.

- ^ Tacitus: Annales. 1, 61, 2-4, translation Erich Heller: Tacitus Annalen. Translated and explained by Erich Heller (1982). Monolingual edition Munich 1991, p. 67.

- ^ Tacitus: Annales. 1, 62, 1.

- ^ Sueton Gaius , 3, 2.

- ^ Tacitus: Annales. 1, 62, 2.

- ↑ Birgit Großkopf: The human remains from the Kalkriese-Oberesch site. In: Gustav Adolf Lehmann, Rainer Wiegels (ed.): Roman presence and rule in Germania during the Augustan period. The find site of Kalkriese in the context of recent research and excavation findings (= treatises of the Akad. D. Wiss. Zu Göttingen, Phil.-Hist Klasse, volume 3, 279). Göttingen 2007, pp. 29-36.

- ↑ Birgit Großkopf: The human remains from the Kalkriese-Oberesch site. In: Gustav Adolf Lehmann, Rainer Wiegels (ed.): Roman presence and rule in Germania during the Augustan period. The find site of Kalkriese in the context of recent research and excavation findings (= treatises of the Akad. D. Wiss. Zu Göttingen, Phil.-Hist Klasse, volume 3, 279). Göttingen 2007, pp. 29–36, here p. 36.

- ↑ Wolfgang Schlüter: Was the Oberesch in Kalkriese the location of the last Varus camp? In: Osnabrücker Mitteilungen, Vol. 116, 2011, 9–32.

- ^ Tacitus: Annales. 1, 63, 2.

- ↑ Erich Koestermann: Die Feldzüge des Germanicus 14-16 AD. In: Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, Vol. 6, H. 4, 1957, P. 429-479, here P. 435 f.

- ^ Heiko Steuer: Landscape organization, settlement network and village structure in Germania in the decades around the birth of Christ. In: Gustav Adolf Lehmann, Rainer Wiegels (Ed.): "Over the Alps and over the Rhine ...". Contributions to the beginnings and the course of the Roman expansion into Central Europe . Berlin 2015, pp. 339–374, here p. 365.