Mattium

Mattium was a main town ( "caput gentis" according to Tacitus ) of the West Germanic tribe of the chat , probably in the area of today's Schwalm-Eder district in northern Hesse . In his annals, Tacitus described the destruction of Mattium by the Roman general Germanicus in AD 15 during the Germanicus campaigns . The equation of Mattium with Altenburg near Niedenstein , which was widespread in older research, has been refuted by new findings (dating of the archaeological finds).

Tradition according to Tacitus

The Chatti settlement area bordered in the east on that of the Hermundurs and in the north on that of the Cherusci , in the west on that of the Martians and in the south on the Roman Empire . For the first time the geographer Strabo mentioned the peasant warriors Chatten. Because of their neighborhood and numerous battles with the Romans in the south, but also because of their participation in the Varus Battle , the chats went down in history. Strabon mentions a daughter of the Chatti prince Ucromirus and a Chatti priestess named Libes, who were taken prisoners during the triumph of Germanicus in 17 AD. Tacitus mentions the Chatti princes Arpus and Agdandestrius, who Tiberius had declared himself willing to murder Arminius by poison , as well as, in connection with the request of the Cheruscans for the installation of a king in AD 47, an Actumerus who should belong to the generation of Arminius. The main source for the existence of a place Mattium is its mention in Tacitus.

The defeat of the Roman legions under Publius Quinctilius Varus in 9 AD and the victory of Arminius in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest did not mean the end of the threat from the Romans for the Chatti. Tiberius advanced again to the Rhine in 10 AD and secured the Roman positions. In 13 AD Tiberius was replaced by Germanicus. Its army grew to the greatest number of troops on an imperial border of Rome . Eight legions were now stationed in Germania. The chats meanwhile penetrated into the Wetterau .

Germanicus decided to strike back, which was also intended to be retaliation for the Chatti participation in the Varus Battle. With four legions and 10,000 auxiliary troops, he followed the Bronze Age Lahnstrasse from Koblenz in 15 AD , which left the Lahn at the mouth of the Ohm and flowed in a north-easterly direction into Weserstrasse. Favored by the persistent drought, Germanicus was able to surprisingly invade the center of the Chatti settlement area around today's Fritzlar . He left the legate Lucius Apronius behind to build solid paths and build bridges, as he expected the Lahn to rise before the march back. At the same time, Germanicus ordered the Legate Caecina with the Lower Rhine Army of four legions and 5,000 auxiliary troops to Haltern am See , with the aim of using the Hellweg to prevent the Cheruscans and Marser from supporting the chat in the fight against the Romans.

This sudden, unexpected and quick advance took the Chattas by surprise, who could no longer offer organized resistance outside their main settlements. Only a team of young chatters tried to prevent the Romans from crossing over the Adrana ( Eder ). They swam across the river, but were repulsed by the use of the Roman throwing machines and arrow shooters.

When peace efforts failed, some Chattas joined the Romans, and most of them were scattered in the surrounding forests. The fighting stopped and Mattium was abandoned. Germanicus incinerated it and left the country devastated. According to Tacitus, the Romans were not attacked any further on the march back to the Rhine. For Germanicus, the destruction of Mattium was sufficient reason to have his advance in Rome recognized as a victory in a great battle.

Mattiaker

Possibly the name of the Mattiaker derives from the place Mattium. In addition to the similarity of the name, this is concluded from the mention of the tribe directly after the Batavern at Tacitus, who also split off from the Chattas . The Mattiaker sat in the area around today's Wiesbaden ( Mattiacum or Aquae Mattiacorum ), which in Roman times became the capital of the Civitas Mattiacorum .

Today's location

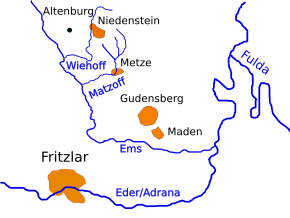

Mattium could not be located exactly until today, but it is generally assumed that it was somewhere in Northern Hesse, probably in the area north of Fritzlar , as Germanicus crossed the Eder before Mattium was destroyed. For a long time, Mattium had been equated with Altenburg near Niedenstein . However, this thesis is considered refuted, since the destruction of the Altenburg and the end of settlement could be dated to the middle of the first century BC.

An exact identification of Mattium with an Iron Age settlement or fortification is not yet possible from the archaeological finds of the epoch. The few references come from linguistic research and refer to the places Metze and Maden as well as the Bach Matzoff , which are assumed to be derived from Mattium. It also remains unclear whether the term caput gentis in Tacitus describes a religious, economic or political center or just a large settlement.

Some historians therefore assume that Mattium was not a limited location, but a larger area that consisted of various individual farms and refuges with ramparts and probably included the plains of Maden , with the Mader Heide , and Metze . The most important religious, political, legal places and institutions of the Chatti were then in this area.

literature

- Werner Guth : Mattium - Onomastic considerations on a historical problem. In: Journal of the Association for Hessian History and Regional Studies, 113, Kassel 2008, pp. 1–16 ( online; PDF, 568 kB ).

- Helmuth Schneider , Dorothea Rohde (Hrsg.): Hesse in antiquity. The chats - from the age of the Romans to everyday culture of the present. euregioverlag, Kassel 2006 (with contributions by Klaus Grote , Jürgen Kneipp, Mathias Seidel, Armin Becker , Irina Görner, and others) - online reading sample

- Armin Becker: Mattium. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 19, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2001, ISBN 3-11-017163-5 , pp. 443-444. ( Excerpt (Google) )

- Eckhart G. Franz (Hrsg.): Chronicle of the state of Hessen. Chronik Verlag, Dortmund 1991, p. 11.

- Karl Ernst Demandt : History of the State of Hesse . Stauda Verlag, Kassel 1981, pp. 23, 31, 63, 84 f, 95 u. 115.

- Georg Wolff : The geographical prerequisites for the chat campaigns of Germanicus. In the journal of the Association for Hessian History and Regional Studies. Volume 50 (1917), pp. 53-123, section Mattium pp. 112-119 ( online ; mostly out of date research).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Tacitus, Annalen 1, 56, 4

- ^ Armin Becker: Mattium. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 19, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2001, ISBN 3-11-017163-5 , pp. 443-444. ( Excerpt (Google) )

- ↑ Strabo, Geography Chapter 7, 1, 4 (p. 161).

- ^ Tacitus, Annals 2, 7.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annalen 2, 88.

- ^ Tacitus, Annals 11, 16.

- ^ Tacitus, Annalen 1, 56.

- ^ Tacitus, Annalen 1, 56.

- ^ Hartmut Galsterer : Communities and cities in Gaul and on the Rhine. In: Gundolf Precht (Ed.): Genesis, structure and development of Roman cities in the 1st century AD in Lower and Upper Germany. Colloquium from February 17th to 19th, 1998 in the regional museum Xanten (= Xantener reports , volume 9). Von Zabern, Mainz 2001, ISBN 3-8053-2752-8 , p. 4.

- ^ Tacitus, Germania 29.

- ^ Moritz Schönfeld: Mattiaci. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume XIV, 2, Stuttgart 1930, Col. 2320-2322. Wolfgang Jungandreas : Chatting. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 4, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1981, ISBN 3-11-006513-4 , p. 378. Harald von Petrikovits ibid. P. 379 ( limited online version in the Google book search).

- ↑ Christian Hänger: The world in the head: spatial images and strategy in the Roman Empire . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 2001, ISBN 9783525252345 , p. 211.

- ↑ H.-G. Simon in D. Baatz, FR Herrmann: The Romans in Hesse . Stuttgart 1989, p. 56.

- ↑ Werner Guth: Mattium - Onomastic reflections on a historical problem. In: Journal of the Association for Hessian History and Regional Studies. 113, 2008, pp. 1–16 ( online; PDF, 568 kB ).

- ↑ For evidence see Armin Becker: Mattium. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 19, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2001, ISBN 3-11-017163-5 , p. 444. as well as Harald von Petrikovits : Chatten. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 4, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1981, ISBN 3-11-006513-4 , p. 379. and Gerhard Mildenberger , ibid. Pp. 385-389.

- ↑ “The center of the Chatti tribe was, as the campaign of Germanicus 15 AD shows, Mattium, whose name caput gentis , head of the tribe, characterizes its meaning. Since Mattium is undisputedly included in the name Metze, the two have rightly been equated locally, whereby it should only be taken into account that the nearby maggot (Mathanon) Mattium is linguistically neighboring and that Altenburg, which is also nearby, was destroyed on the train of the Germanicus has been. This already shows that Mattium was not a limited locality, but an entire district that encompassed the most important political, legal and religious sites and institutions of the tribe. ”In Karl Ernst Demandt : History of the State of Hesse . Bärenreiter Verlag 1959, p. 73 below.