Roman camp Haltern

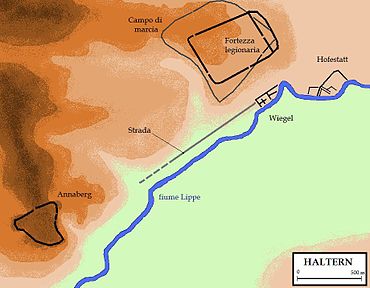

Several Roman military installations in the area of the city of Haltern am See ( Recklinghausen district ) are referred to as the Haltern Roman camp . Military installations and a burial ground from Augustan times have been discovered there since 1816 at a total of six locations . The complex was probably built at the beginning of our era just north of the river Lippe (Lupia) . It was abandoned again in connection with the events surrounding the Varus Battle . As scientists suspect today, the facilities initially had a purely military function and secured the Lippe as a shipping route. Later they also gained importance as an administrative center and trading center. Evidence suggests that the Aliso camp, mentioned by Roman historians in connection with the Varus Battle, was in what is now Haltern.

Research history

The discovery of the former Roman camps in Haltern dates back to 1816. In a correspondence, the Upper President Ludwig Freiherr von Vincke noted that close to the “St. Annenberg “near Haltern, three burial mounds including Roman finds were excavated. In 1834 Pastor Joseph Niesert published a report from the Annaberg. Finally, in 1838 , the Prussian major Friedrich Wilhelm Schmidt examined the routes on which Roman troops had set out into the interior of Germania at the time of Emperor Augustus. He came across the remains of a Roman fort on Annaberg, which is southwest of the city on the north bank of the Lippe . It was not until 1899 that archaeologists excavated the remains of what had been five Roman sites from the Augustan era and also discovered a burial ground from that time. Since then, many excavation campaigns have taken place, which, despite the difficulty of advancing settlement activity, have brought essential new knowledge about the development and function of this site.

Investments

Annaberg

In the summer of 1899, the archaeologist Carl Schuchhardt found a ditch on the Annaberg plateau, which towers over the Lippe valley by around 30 m, the course of which could be almost completely clarified by means of search cuts. This 3.5 m wide and 1.5 m deep pointed trench was part of the defense of an approximately 7 hectare camp. It was roughly triangular in shape. Behind the ditch there was an earth wall, reinforced with posts at small intervals, about 4 m wide and 1.5 m high. Other post marks in the pointed ditch indicate that towers were built into the wall at a distance of 30 m. What is unusual about it is that the towers would have been partially outside the wall. The findings on the two double-leaf gate systems are also unclear. The gatehouses to the right and left of the 4 m wide driveways should also have protruded several meters over the Spitzgraben. Overall, the picture is untypical for military installations from the Augustan period.

Cradle

In August 1899 , the Haltern doctor Alexander Conrads discovered fragments on the Wiegel parcel that were dated to be Augustan. To the north of a terrace edge facing the Lippe floodplain, three excavation campaigns investigated a 300 m long and 60 m wide section of land. There was a confusing coexistence of several trenches and pits. A ditch around 220 m long delimited this site to the north. While it became flatter and narrower in an easterly direction, it turned off to the south in a westerly direction. There, after about 30 m, it flows into a system of three to seven meters wide pits of different lengths - the so-called "triangle" because of the arrangement of the pits to each other. To the west of it was a 13 × 18 m building, the southern front of which facing the Lippe was half open. No less than eight pointed trenches crossed this site.

Court seat

Between 1901 and 1904 the archaeologists Friedrich Koepp , Hans Dragendorff and Gustav Krüger excavated four consecutive, overlapping fortifications on the Hofestatt corridor . They all faced the southern lip and were open to the river. This fact has led to the fact that they are also called "Uferkastell" in the professional world.

- The oldest system was also the smallest. It was about 43 x 10 m. It was surrounded by a 2 m wide and around 1 m deep pointed ditch, which was executed twice in the eastern half of the complex. Behind the trenches was an approximately 3 m wide wood-earth wall .

- The next younger system enclosed the first over a large area. Its about 115 m long straight north side curved at its end in a southerly direction towards the Lippe. Here, too, a pointed ditch was found with a wood-earth wall behind it. Post marks on the northeast corner suggest that there was a tower there. In the middle of the north side there was an approximately 3 m wide earth bridge, possibly the gate to this camp site. The outlines of two buildings were found inside the camp on both sides of these gates.

- The third system was apparently changed by the Romans during the construction phase. Beginning at the southwest corner of its predecessor, the originally planned course, apart from a shallow bend, ran more than 220 m in a north-easterly direction, and then bend about 50 m to the south-east. This system was provided on the west side with a length of around 75 m with a double pointed ditch and a wood-earth wall. In its further course only the outer pointed ditch was found. A gate system was planned roughly in the middle of the fence running to the north-east, which is indicated by a wide earth bridge over the Spitzgraben. In fact, this facility was eventually completed much smaller. It was about half the size of the second fortification and overlaid it in its western half. The already mentioned double ditch now bent to the southeast and ended at the embankment to the Lippe. On the northeast side there were also a gate system and traces of smaller buildings.

- The youngest of all the plants found was also the largest. Beginning about 90 m west of the other fortifications, their two pointed trenches and their wood-earth wall initially ran north, then turned at right angles to the east, to finally flow into the eastern trenches of the third complex. There was a gate on the western front; the trenches were interrupted there by an earth bridge about three meters wide. In the northwest corner of this fortification, the excavators found the traces of a 55 × 30 m building complex open to the Lippe: the remains of seven parallel ship houses - comparable to our present dry docks. Each of these houses was about 30 m long and 6 m wide.

Encampment

Excavation findings in the Hofestatt corridor led the archaeologists to track down the complex known as the "field camp". It is located on an elevation up to 30 m high northwest of Wiegel and Hofestatt. After several investigations, the size of the camp was determined in 1909: It was approximately pentagonal in shape and about 614 × 560 m in size, which corresponds to an area of about 34.5 hectares. It was surrounded by a 1.6 m deep and up to 2.8 m wide pointed ditch. Gates were found on the north, east and south sides of the camp. An approximately 3 m wide no-find zone behind the ditch on the inside of the camp indicates a wall. Traces of an interior development have not been proven in the previous excavations. In the north trench there was a cultural layer with considerable amounts of charcoal, slag and Roman finds.

Main camp

A pharmacist from Haltern had discovered Roman finds in a ravine in 1901. During the investigation of the site by Friedrich Koepp, Friedrich Philippi and Carl Schuchhardt, it turned out to be the outer part of a double- pointed trench that surrounded the "main camp" and whose course Otto Dahm was able to clarify almost completely. Both trenches were about 6 m wide and 2.5 m deep. An approximately three meter wide wood and earth wall followed inside. It enclosed an area of 16.3 hectares. During the investigation, the archaeologists discovered that the camp had been enlarged by about 1.6 hectares to the east at a time that could not be determined. In the last stage of expansion it had an area of about 560 × 380 m and covered an area of 18.3 hectares. There were four gate systems in the fence, with the gate lanes being seven to ten meters wide. A track of posts near the west gate indicates a storage tower. The double trenches of the main camp cut several times through the trench of the field camp - discovered later - which must therefore have been dug earlier than the main camp.

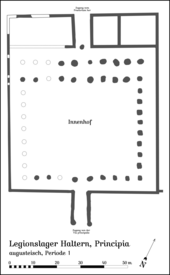

By the First World War, the excavators had discovered a system of streets running almost at right angles to one another within the camp area next to the four main streets of the camp ( Via principalis , Via praetoria, Via decumana, Via quintana) . The Via praetoria was over 45 m, the Via principalis 30 m, the Via decumana and Via quintana up to 20 m wide. The via sagularis ran parallel to the fence inside the camp . The interior development showed the spectrum of buildings to be expected for a Roman camp of this size: in addition to the administrative headquarters ( Principia ) and the camp commandant's quarters ( Praetorium ) , there were tribune houses, centurion houses, barracks buildings ( Contubernium ) , a hospital ( Valetudinarium ) , warehouses, pottery, storerooms and workshops. What is striking is the unusually high number of buildings of a representative character and the subsequent construction of new buildings in the street space.

East camp

The east camp was discovered in 1997. In 2000 a clavicle gate was found that was previously only known from camps that were built at the end of the first century of the calendar.

Burial ground

The first burial mounds were found and excavated near the Annaberg in 1816. Excavations on the eastern slope of the Annaberg took place in 1925 under August Stieren and in 1932 under Christoph Albrecht , during which Augustan cremations were found. In 1958, another Augustan grave was discovered in this area by chance. When a grave was discovered about 500 m to the east, planned excavations began in 1982, during which a further 32 graves were discovered by 1988. The grave field discovered so far extends over a length of approximately 500 m on an approximately 45 m wide strip from the southeast corner of the field and main camp to Annaberg. In all cases it is cremation, with saucepans being used as urns. The grave goods almost always include small bottles of anointing oil. Remnants of jugs and other dishes as well as nails that could have come from the deathbed of the deceased, but also from their shoes, were often found. Hundreds of fragments of bone, which were decorated with carvings, also indicate death beds.

Finds

The range of finds is extensive, as the following overview shows.

- Coins: four gold coins, 309 silver coins, 2561 copper coins (soldiers' cash).

- Construction equipment / living: lead pipes (water pipes), tent pegs, lamps, candelabras, remains of locks and keys.

- Ceramics / Glass: high-quality fine ceramics, functional ceramics, colored glass (millefiori glass, radicella thread glass, striped mosaic glass, single-colored colored glass), game pieces.

- Tools: lead weights, axes, hoes, pliers, sickles, dolabras, construction clips, wall hooks, lead solders, lead ingots, bronze ingots, anvils, molds, hand drills, hammers, saws.

- Weapons: daggers, helmets, shield humps , sword scabbards, three-winged arrowheads, hurl lead, pilum and lance tips, catapult arrows, handcuffs.

- Eating / drinking / cooking: jugs, pots, bowls, plates, cups, amphorae, baking plates, ladles, sieves. The place of discovery is the eponym of the Haltern saucepan .

- Cult: urns, death beds, bowls and other cult vessels, cult figures.

- Medicine: Pharmacopoeia, probes, needles, tweezers, vials, jug, scrapers.

- Riding: harness fittings, bridles, lever arm hooks, bronze bells.

- Clothing / jewelry: bronze buckles with remains of leather straps, belt clasps, jewelry discs, buttons, brooches, rings, gems, amulets, pendants.

Dating

It is not yet clear when the Haltern warehouse complex was founded. So far, the time of the foundation can only be assigned by comparing the Haltern finds with those of other, already firmly dated sites. From the range of shapes of the ceramic finds it can be deduced that Haltern was only a few years after the abandonment of the Oberaden Roman camp, which was established no later than 8 BC. Was abandoned, was founded. In the historical sources for the period from 7 BC From BC to AD 1, there was no recognizable reason for building such a military complex. There is therefore some evidence that Haltern is related to the unrest in Germania of the year AD 1 mentioned by the Roman writer Velleius Paterculus , to which the Romans reacted with campaigns under Marcus Vinicius ( immensum bellum ) . A foundation from the years 7–5 BC. Chr. Is not excluded, however; In these years the infrastructure on the right bank of the Rhine was restructured after the end of the Drusus campaigns (12 to 8 BC).

The camp complex at Haltern was only used by the Romans until 9 AD. Using coin statistics, Konrad Kraft was able to prove this assumption plausibly for the first time in 1956. It was confirmed in later years by Bernard Korzus and others due to the continued increase in the number of coins.

Among other things, three hoard finds speak for the abandonment of the camp in connection with the Varus Battle. In addition to a box containing more than 3,000 arrows, another hoard with weapons and other metal objects and a treasure trove of gold and 186 silver coins were discovered that were worth roughly the annual salary of a soldier at the time.

function

Despite its suitable location, the camp on Annaberg puzzles scientists because it does not fit the picture of other Augustan military installations. Its function has not yet been clarified. The same applies to the Wiegel site on the edge of the high terrace facing the Lippe floodplain. Initially, it was suspected that it was a berth for ships equipped with storage structures. Then, however, the lip should have flowed directly past the edge of the terrace, which is considered unlikely. The many settlement finds made of coins, fibulae, fine ceramics and stained glass, which one cannot expect in high numbers at a port facility, also do not fit this assumption.

According to the findings, the fourth, i.e. youngest, fortification at the Hofestatt is clearly a fortified naval base. The function of the systems previously built at this point is unclear. Even if a use as a paved landing area for ships can be assumed there, this has not yet been confirmed by findings.

The camp complex was apparently no longer used solely for military purposes when it was abandoned. The assumption of an also administrative and civilian use is based on several findings. On the one hand, the warehouse was considerably enlarged. But this was apparently not done to make room to accommodate more soldiers. Instead, there are indications that barracks were demolished in order to build workshops. Further indications are the construction of a new tribune house and a storage building after the warehouse expansion, the reconstruction of several buildings, the construction of new tribune houses in the camp streets and the fact that the camp complex contained more buildings for senior officers than would have been necessary for a warehouse. According to Siegmar von Schnurbein , the camp could only accommodate six or seven cohorts and a few contingents of auxiliary troops .

At a later point in time, the camp's ceramics production apparently no longer served the sole purpose of meeting its own needs. Finds of terra sigillata imitations and glazed ceramics suggest this conclusion. Through the discovery of high-quality ceramics produced in Haltern, trade relations up the Lippe to the Roman camp Anreppen and down the Lippe to the Rhine and along this to Mainz and Wiesbaden can be proven.

In conclusion, it can be said that when Haltern was abandoned, it was changing from a purely military complex to which civilian importance also increasingly assumed. This fits in with the descriptions of the ancient writers Tacitus and Cassius Dio . Tacitus reported in his Annals (1, 59) of Arminius that he had spoken of new settlements ("novas colonias") in a speech against the Romans; In his work Roman History , Dio described that the Romans had built the first cities (“Polis”) and markets (“Agora”) in the area on the right bank of the Rhine at the time in question. While in Lahnau-Waldgirmes an der Lahn such a city was discovered from the Augustan era, Haltern served more as a trading center due to the finds and findings.

It is unclear which troops were once stationed in Haltern. Two finds indicate the temporary presence of at least parts of the 19th Legion , which perished in the Varus Battle : a terra sigillata plate with the incised inscription of a soldier with the less common name Fenestela, whose tombstone found in Frejus identifies him as a member of this legion; a lead bar found in the main camp, on which there is also a reference to the 19th Legion.

The area today

Major parts of the former camp complex are built over today. One of two exceptions is the western area of the field and main camp. The area on the western edge of the city of Haltern am See is enclosed by settlement areas and is used for agriculture today. The site on Annaberg is now wooded. The LWL Roman Museum was built between the southern defenses of the field and main camp and follows their course through the shape of the building. The skylights in the green roof of the low-rise building are also reminiscent of the tents of the Roman soldiers who camped on this site 2000 years ago. The finds from the other camps discovered so far on the Lippe - Anreppen , Beckinghausen , Holsterhausen , Oberaden - as well as those from the Roman camp Kneblinghausen are also exhibited in the museum. From May 16 to October 25, 2009 the exhibition illuminated Imperium. Conflict. Myth. 2000 years of Varus Battle at the original locations of Haltern am See, Kalkriese and Detmold, different facets of historical events.

literature

- Siegmar von Schnurbein : The Roman military installations at Haltern. Report on the research since 1899 (= soil antiquities of Westphalia. Issue 14). Aschendorff, Münster 1974 (2nd edition Münster 1981, ISBN 3-402-05117-6 ).

- Rudolf Aßkamp , Renate Wiechers: Westphalian Roman Museum Haltern. Edited by the Westphalian Roman Museum, Haltern, on behalf of the Regional Association of Westphalia-Lippe. Ardey-Verlag, Münster 1996, ISBN 3-87023-070-3 .

- Rudolf Aßkamp: Haltern. In: 2000 years of Romans in Westphalia. Mainz 1989, ISBN 3-8053-1100-1 , pp. 21-43.

- Rudolf Aßkamp: Haltern, city of Haltern am See, Recklinghausen district (= Roman camp in Westphalia. Issue 5). Antiquities Commission for Westphalia, Münster 2010.

- Johann-Sebastian Kühlborn : The Augustan military base Haltern. In: Johann-Sebastian Kühlborn (Ed.): Germaniam pacavi. I pacified Germania. Münster 1995, pp. 82-102.

- Johann-Sebastian Kühlborn: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde 13. Berlin 1999, S. 460–469 Haltern.

- Johann-Sebastian Kühlborn: Haltern. In: Michel Reddé, Raymond Brulet, Rudolf Fellmann, Jan Kees Haalebos, Siegmar von Schnurbein (eds.): L'Architecture de la Gaule romaine. Les fortifications militaire. ISBN 2-7351-1119-9 , Paris 2006, ISBN 2-7351-1119-9 , pp. 285-290.

- Johann-Sebastian Kühlborn: The Augustan main camp of Haltern. In: War and Peace. Celts, Romans, Teutons. Primus-Verlag, Darmstadt 2007, pp. 203-206.

- Johann-Sebastian Kühlborn: On the march in the Germania Magna - Rome's war against the Teutons. In: Martin Müller , Hans-Joachim Schalles, Norbert Zieling (eds.): Colonia Ulpia Traiana. Xanten and its surroundings in Roman times. Zabern, Mainz 2008, ISBN 978-3-8053-3953-7 , pp. 67-91.

- Joachim Harnecker: Catalog of the iron finds by Haltern from the excavations of the years 1949–1994. Zabern, Mainz 2001, ISBN 3-8053-2452-9 .

- Bernhard Rudnick: The Roman pottery from Haltern. Zabern, Mainz 2001, ISBN 3-8053-2796-X .

- Martin Müller: The Roman non-ferrous metal finds from Haltern. Zabern, Mainz 2002, ISBN 3-8053-2881-8 .

Web links

- Roman Museum Haltern

- Jona Lendering: Holders . In: Livius.org (English)

- History of the research of the Roman Haltern on the side of the Heimatverein Haltern

Individual evidence

- ↑ Archaeological evidence confirms: Haltern was probably the ancient Aliso. Press release from August 12, 2010.

- ↑ Journal for antiquity studies . Volume 5, 1838, pp. 1202 ff.

- ^ Rudolf Aßkamp: Haltern. In: 2000 years of Romans in Westphalia. Zabern, Mainz 1989, ISBN 3-8053-1100-1 , p. 21.

- ^ Ferdinand Oppenberg : The Hohe Mark Nature Park . Mercator-Verlag, Duisburg 1974, ISBN 3-87463-060-9 , p. 82.

- ↑ Aßkamp: Haltern. 1989, pp. 24, 27-28.

- ↑ Aßkamp: Haltern. 1989, pp. 24, 28-29.

- ↑ a b Aßkamp: Haltern. 1989, p. 24.

- ↑ Aßkamp: Haltern. 1989, p. 30.

- ↑ Aßkamp: Haltern. 1989, p. 31.

- ↑ Aßkamp: Haltern. 1989, p. 31 f.

- ↑ Aßkamp: Haltern. 1989, p. 32 f.

- ↑ Aßkamp: Haltern. 1989, pp. 33-34.

- ↑ Aßkamp: Haltern. 1989, pp. 34-35.

- ↑ Aßkamp: Haltern. 1989, pp. 39-41.

- ↑ Konrad Kraft: The end date of the legion camp Haltern. In: Bonner Jahrbücher 155–156, 1955/56, pp. 95–111.

- ↑ a b Aßkamp: Haltern. 1989, p. 41 ff.

- ^ Siegmar von Schnurbein: News on Germania under Varus. . In: Varus-Gesellschaft (ed.): Varus-Kurier . Georgsmarienhütte , December 2000, p. 10 f.

- ^ Tacitus: Annals. 1, 59.

- ^ Cassius Dio: Roman History. 56, 18, 2.

Coordinates: 51 ° 44 ′ 22.1 ″ N , 7 ° 10 ′ 13.9 ″ E