Altona district

|

Altona district of Hamburg |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coordinates | 53 ° 33 ′ 0 ″ N , 9 ° 56 ′ 0 ″ E | ||||||||||||

| height | 20 m above sea level NHN | ||||||||||||

| surface | 77.4 km² | ||||||||||||

| Residents | 275,264 (Dec. 31, 2019) | ||||||||||||

| Population density | 3556 inhabitants / km² | ||||||||||||

| Postcodes | 20257, 20357, 20359, 22525, 22547, 22549, 22559, 22587, 22589, 22605, 22607, 22609, 22761, 22763, 22765, 22767, 22769 | ||||||||||||

| prefix | 040 | ||||||||||||

Administration address |

District Office Altona Platz der Republik 1 22765 Hamburg |

||||||||||||

| Website | www.hamburg.de/altona | ||||||||||||

| politics | |||||||||||||

| District Office Manager | Stefanie von Berg ( Greens ) | ||||||||||||

| Allocation of seats ( district assembly ) | |||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Transport links | |||||||||||||

| Highway |

|

||||||||||||

| Federal road |

|

||||||||||||

| Long-distance and regional trains |

|

||||||||||||

| S-Bahn and U-Bahn |

|

||||||||||||

| Source: Statistical Office for Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein | |||||||||||||

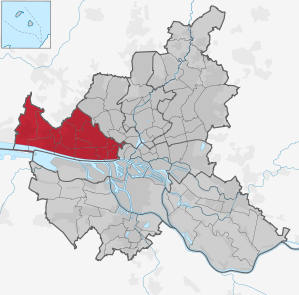

The Altona district is the westernmost of the seven districts of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg . It is largely identical to the town of Altona, which was independent until 1938 - apart from the fact that Eidelstedt and Stellingen - Langenfelde now belong to the Hamburg district of Eimsbüttel and the border with St. Pauli has undergone some changes.

geography

location

Altona borders in the south and east on the Hamburg-Mitte district , in the northeast on the Eimsbüttel district and in the north and west on the state of Schleswig-Holstein . In the southwest, in the middle of the Elbe and across the uninhabited Elbe island Neßsand, the border between Altona and Lower Saxony runs .

Districts

The district consists of 14 districts, which can be classified into three types in terms of building density and population density (2001):

- the eastern districts of the district ( Altona-Altstadt , Altona-Nord , Ottensen and the Sternschanze district, newly created in February 2008 ), which essentially correspond to the old town center, with 9400 to 11,300 inhabitants. / km² (largely apartment buildings)

- the northern districts ( Bahrenfeld , Groß Flottbek , Iserbrook , Lurup , Osdorf ) with 2300 to 5000 inhabitants / km² (mixed development)

- the western Elbe suburbs ( Blankenese , Nienstedten , Othmarschen and Rissen ) including the partly rural Sülldorf with 900 to 1800 inhabitants / km² (mostly single houses and villas).

geology

In terms of landscape, the district is divided into three strips running parallel to the Elbe, over about 15 km in a west-east direction:

- the very narrow, un-diked Elbe beach , limited to the hinterland by the steeply rising Geesthang ;

- the high bank formed by the Ice Age ( terminal moraine wall ), which rises to around 90 m in Blankenese (Falkenstein, Bismarckstein, Süllberg ) and is only flattened in a few places by the confluence of streams: at the fish market through the Pepermölenbek , in Teufelsbrück through the Flottbek ;

- the mostly flat Geest , which adjoins inland and is still used for agriculture in the northwestern part (Osdorfer or Sülldorf-Rissener Feldmark) and with the Klövensteen also has a larger forest area.

story

Beginnings

The first mention of Altona was the in 1537 Krugwirtschaft Fisherman Joachim from the blaze , still under the name Altena . Altona was built around the Krug as a fishermen's and craftsmen's settlement, which was promoted in the spirit of mercantilism by the sovereigns, the Counts of Holstein-Pinneberg .

The settlement was probably on the Geest slope between the later Nobistor and the Altona fish market in the area of today's Pepermölenbek street. The name could be derived from the fact that, in the opinion of the Hamburg council, the place was "all to nah" ( too close ) to the city limits. According to linguistic derivation, the name Altona comes from the now no longer existing, upstream stream Aldenawe or Altenau , which is shown in Melchior Lorichs' Elbe map from 1568 and in Dankwerth's chronicle from 1652.

Partly on Altona soil was a small settlement on the Pepermolenbach, which is mentioned in a document from the Herwardeshude monastery in 1310 . This document also mentions Ottenhusen for the first time , to whose Bailiwick , established in 1390, Altona later belonged.

In addition, there is little evidence of possible earlier settlements in today's Bahrenfeld between Schnackenburgallee and Altonaer Volkspark. A connection with Odin / Wotan and Hel was derived from the place name “Winsberg” or the street “Winsbergring” and the street “Hellgrundweg” and the existence of Germanic sacrificial sites was derived from it - although this was not proven by written sources or archaeological finds .

Early modern age

From the beginning there were disputes between Hamburg and Altona about grazing and minting rights, guild and religious questions and the use of the Elbe. In 1591 a border war broke out, which was also fought before the Reich Chamber of Commerce and only ended in a settlement in 1740. Likewise, Hamburg did not accept Altona's city privilege from 1664 until 1692 ( Copenhagen Recess ).

Religious tolerance has a longer tradition in Altona than in Hamburg. The Protestant sovereign Count Ernst von Schauenburg and Holstein-Pinneberg , who ruled from 1601 to 1622, sponsored Altona by granting generous privileges . As early as 1601, the Reformed and Mennonites who had fled from the southern Netherlands were granted the privilege of freely practicing their religion. Both religious communities still form parishes in Hamburg-Altona today. In 1658 the Catholic community also received the privilege of freedom of belief .

During the Thirty Years' War , Altona got caught up in the conflict between Denmark and Hamburg. During this time, Altona suffered badly from the Danish soldiers, and in August 1628 around 140 people per week died from the plague in the city . On the other hand, a splendid avenue was laid out between 1638 and 1639, the Palmaille . To protect the population from hordes of marauding former mercenaries, Count Otto V. von Schauenburg and Holstein-Pinneberg approved the establishment of a "rifle company" as a vigilante and fire guild in 1639. Later it got the name Altonaer Schützengilde from 1639 , under which the guild exists until today (since 1864 however as a private association). In 1644/45 Altona came temporarily into Swedish possession.

After the extinction of Schauenburg line-Holstein Pinneberg 1640 Altona dropped as part of the Principality Pinneberg to the Danish king, who is also with the imperial fiefdom Holstein in personal union reigned as Duke. Altona therefore remained part of the Holy Roman Empire until 1806 and of the German Confederation from 1815 , but was under Danish administration until 1864 with the resulting adjustments such as B. the applicable customs law and currency .

On August 23, 1664, the Danish King Friedrich III. Altona the city rights ; this privilege included, among other things, customs, stacking and trade freedoms as well as jurisdiction . In 1683 a municipal Latin school was founded, which was expanded in 1738 to a grammar school, which still exists today under the name Christianeum . Since the middle of the 18th century, numerous students from Altona's Jewish families have also been accepted here.

Altona developed into an important press location in the 17th century because of the greater tolerance of the authorities compared to Hamburg. Renowned and long-lived newspapers appeared here, in particular the Altonaische Mercurius (1698–1874) and the (Altonaische) Reichs-Post-Reuter (1699–1789).

During the Danish siege of Hamburg (1686) , Altona was badly damaged by Hamburg artillery fire.

18th century

With around 12,000 inhabitants in 1710 and around 24,000 inhabitants in 1803, Altona was the second largest city in the entire Danish state after Copenhagen .

The magistrate of the city of Altona was headed by an upper president appointed by the Danish king .

In the course of the Great Northern War , it was set on fire in January 1713 by soldiers of the Swedish general Stenbock . Starting in the east, house by house was set on fire as planned. This explains (around 60% of the buildings were destroyed) that, apart from the Palmaille streets, almost nothing is reminiscent of the Altona before the “ Swedish fire ”.

Christian Detlev von Reventlow , who was appointed senior president in the same year, is considered to be the city's new founder; u. a. he obtained extensive rights from the king to rebuild it. Ottensen and Neumühlen were also subordinate to him . With Claus Stallknecht , who also built the old town hall near the Nobistor (official seat until 1898, destroyed in 1943), a city architect was appointed. The time from the reconstruction to the continental dam (1807) was described by the chroniclers as the "golden era" of Altona.

In the late 18th century, Altona developed into a center of the Enlightenment in northern Germany, personified in particular from 1757 in the social reformist city physician and poor doctor Johann Friedrich Struensee , who from 1769 initially worked as personal physician to the Danish King Christian VII , then as ennobled secret cabinet minister within in just 16 months passed several hundred laws and ordinances to modernize the state of Denmark . Struensee was executed by the representatives of the "old order", deprived of their influence, after a show trial in 1772 in Copenhagen . In Altona, a copper plaque on a house on Kleine Papagoyenstrasse commemorated him. Like the other houses on the street, the house had survived the Swedish fire, but was demolished in 1937 as part of the National Socialist urban redevelopment.

Altona has always understood itself as an “open city”, as symbolized by the coat of arms with the open gate; Politically or religiously persecuted people as well as people who were not tolerated elsewhere for economic reasons are accepted here: Dutch Reformed, Huguenots , Mennonites , Jews , non-guild craftsmen, and destitute residents of Hamburg expelled by the Napoleonic occupiers (winter 1813/14), but also long-forgotten sects such as Adamites , Gichtelians or separatists . They enjoyed the intellectual and economic freedoms that “Hamburg's beautiful sister” offered them and, for their part, contributed in many ways to the development of the city. The Jewish burial places or the street names Kleine and Große Freiheit illustrate this climate of tolerance in Altona on the city map. These streets were assigned to the St. Pauli district in 1938 . The construction of the Catholic St. Joseph's Church had already started in 1718 .

Accordingly, the six city gates that have separated Altona from Hamburg's suburb "Hamburger Berg" (today St. Pauli) since 1740 are more open border markings: from the banks of the Elbe upwards, the Pinnas, Schlachterbuden, Drum, Nobis, Hummeltor as well as the nameless northernmost gate Passage near the road at the green hunter . The southern location of the five named gates clearly shows that Altona was mainly built near the Elbe even in the 18th century.

In 1742/43 the main church of St. Trinity was built. The monograms of the two Danish kings Christian V and Christian VI. on the sandstone portals show the importance attached to the large new main church in what was then the second largest city in the entire Danish state. A new tower had stood in front of an older church since 1694. The Altona master carpenter Jacob Bläser had built it and crowned it with a curved spire in Dutch style. For Altona it became a landmark, and of course it should also compete with the Hamburg towers. When the old church became dilapidated, the Holstein builder Cay Dose was commissioned to build the new church. Dose planned the new large church on a cross-shaped floor plan following the Bläser tower .

The ideas of the French Revolution also met with approval in Northern Europe: In Altona, republican-minded intellectuals and - unusual for the time - individual members of the urban lower classes founded a Jacobin Club in 1792 , which regularly met in a hostel on Altona's town hall market. The actions of its members were limited to the spreading of enlightening and revolutionary ideas by wildly posting leaflets; the king's head was not threatened. Christian VII initiated several laws in the same year, probably also to take the wind out of the sails of overly democratic aspirations, through which compulsory schooling was introduced and essential steps were taken towards the emancipation of Jews .

The long 19th century

The dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire (1806) through the Napoleonic Wars and membership in the German Confederation (1815) changed little politically for Altona - as for the Duchy of Holstein as a whole: it was still administered by the Danish king and included in Danish politics and promoted by it. Economically, however, Altona's "golden age" ended abruptly with the Napoleonic Continental Barrier: the total blockade of the Elbe brought many trading houses, shipping companies and export-oriented businesses to the brink of ruin.

By a privilege of King Friedrich VI. The astronomy professor Heinrich Christian Schumacher received the permission to build an observatory at the Palmaille (1821), which he maintained largely from private funds and royal grants and which quickly gained a high scientific reputation. The Astronomical News was also published here. After Schumacher's death (1850), the observatory continued to be operated under changing directors and with scarce resources until it was relocated to Kiel in 1872; the building was destroyed in an air raid in 1941.

Altona was the first free port in Northern Europe (since 1664); through this, but also through the forward-looking planning under Mayor Carl Heinrich Behn ; † 1853, which provided for a considerable northern expansion (which was realized at the end of the century), the city experienced an economic boom.

Schleswig-Holstein's first art street , the Altona-Kieler Chaussee , linked Altona and Kiel from 1833. 1839 saw the regional birth of the (initially privately operated) local passenger transport : the Basson horse-drawn bus line started operating between Altona and Hamburg and helped to cope with the growing traffic between the neighboring cities.

In the pre- March period, Altona also formed, although it had always been favored by the Danish kings since 1640, resistance to the growing danization efforts under Christian VIII and Friedrich VII. An Altona merchant supported the ultimately unsuccessful Schleswig-Holstein uprising (1848-1852) against the Crown (March 23, 1848) with 100,000 marks Courant . Many residents of Altona cheered the German troops marched into the city at Christmas 1863 . After Denmark's defeat in the German-Danish War (1864), Schleswig and Holstein were initially administered jointly by Prussia and Austria as a condominium . With the Gastein Convention of August 14, 1865, Holstein came under Austrian administration. After the Austro-Prussian War , Schleswig-Holstein as a whole became the Prussian province of Schleswig-Holstein in 1867 and, as such, part of the German Empire in 1871 .

The IX. Army Corps and, in the First World War , the IX. Reserve corps had their general command in the Palmaille . In 1871 Altona also became the new garrison of the infantry regiment "Graf Bose" (1st Thuringian) No. 31 . The heroic monument of the 31st at St. John's Church was surrounded in 1996 with depictions of suffering people on three glass panels by the Altona artist Rainer Tiedje.

Enthusiastic about the ideas of the struggle for freedom, the German gymnastics movement also came to Altona. On November 15, 1845, A. F. Hansen founded the Altonaer Turnverein with the aim of "making the methodical training of physical strength the common property of the whole youth, of all classes and classes." In 1846 the first gymnasium in Northern Germany was built, a half-timbered shed on Turnstrasse. In the turbulent years up to 1870, the hall was also used as a vigilante guard, to accommodate Danish prisoners and as a stable for the Austrian cavalry. In 1877 the club built a new gym a little further east, between Königstrasse and Kleiner Mühlenstrasse . In 1878 the Ottensen men's gymnastics club was founded in Ottensen, which was still independent at the time .

On June 20, 1850, the Altonaer Nachrichten was the first daily newspaper in the greater Hamburg area. The printer H. W. Köbner was the publisher. The expedition was at Breite Straße 76, in the so-called Rolandsburg . This house was built by President Roland in 1665 and survived the Swedish fire. In the 1880s it was demolished for road widening. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Altonaer Nachrichten went to the Altonaer Druck- und Verlagsgesellschaft . In 1924 it was taken over by the publishing house and the Hammerich & Lesser printing company in Königstrasse . Hammerich & Lesser was taken over in 1909 by Hinrich Springer, Axel Springer's father , and I. Wagner. The Altonaer Nachrichten appeared until it was banned in 1941 and again from 1948 to 1988, in recent years only as a local supplement to Springer's Hamburger Abendblatt .

On June 16, 1842, the Altona-Kieler Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft was constituted and on June 28 of the same year it received the royal Danish concession to build and operate the King Christian VIII Baltic Sea Railway . This connected Altona with Kiel from 1844 . In 1866 the Hamburg-Altona connecting line to the Hamburger Bahnhof Klosterthor was built, in 1867 a line to the Pinnebergischen Blankenese , the Altona-Blankeneser Eisenbahn .

From 1845 an inclined plane connected the Altona harbor with the train station. After the renovation in 1876, the port railway led down to the banks of the Elbe instead , for which the longest railway tunnel in northern Germany after the station was relocated , the so-called " Schellfisch Tunnel ", was built (closed in 1992). In 1884, the Royal Railway Directorate Altona was set up for the Schleswig-Holstein Railways . In the same year, the Altona-Kaltenkirchener Eisenbahngesellschaft AG ( AKE , since 1916 AKN ) started passenger and freight traffic between Altona and Kaltenkirchen . It was extended to Bad Bramstedt in 1898 and to Neumünster in 1916 . At the beginning of 1886, the Altona-Kieler Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft became the property of the Prussian state and expanded the existence of the Prussian state railways .

The neighboring Ottensen (growth from 4,660 (1855) to 25,500 (1890) inhabitants) benefited from industrialization more than Altona due to changing customs borders (1854, 1867) until 1888. The dominant industries included glassworks and tobacco processing (cigar turner called "beeper", mostly from home ), from 1865 the iron and metal industry (foundries, machine, steam boiler, ship propeller construction), food and beverage production, breweries and, above all, fish processing companies - In 1913 Altona is Germany's largest landing place and industrial location for fish. On January 2, 1911, the Altona harbor towage opened , which was maintained until 1949.

In 1863 a private company set up a museum on the Palmaille, which was taken over by the city in 1888 and opened its doors in 1901 in a new building in the new city center as the Altona museum of regional history .

On June 20, 1880, the North German Racing and Trotting Club in Bahrenfeld , at the gates of Altona, opened a trotting track of 1320 meters in length with stables and stands.

In 1889 Ottensen were incorporated with Neumühlen , in 1890 Bahrenfeld , Othmarschen and Övelgönne . As a result of this and immigration as a result of industrialization, Altona's population grew rapidly: from 40,626 (1855) to 84,099 (1875) to 143,249 (1890) inhabitants.

In 1895, about 500 meters north of the "Danish", a new Altona central station , also in the form of the "Prussian" ; this relocation made it possible to create more spacious railway operating areas and at the same time two east-west road connections between old Altona and its new, western districts. The previous station was used as a town hall after renovations from 1898 , the previous railway area between the old and the new station became a large urban square ("Kaiserplatz", during the Nazi era temporarily "Adolf Hitler" and since then "Platz der Republik") redesigned with representative peripheral development. This complex marked the westward migration of the city center, which until then had been closer to Hamburg and the Elbe.

At the turn of the century, more and more sports clubs were founded, which gradually built their own sports facilities; in 1893 the Altona Cricket Club was founded in 1893 by high school students and young business people. Whitsun 1903, the club, now renamed the Altona Football Club from 1893 (Altona '93), hosted the very first final of the German football championship on the parade pasture in Bahrenfeld. The club has owned the AFC-Kampfbahn on Griegstrasse since 1909 (renamed Adolf-Jäger-Kampfbahn in 1944 ). The Hamburg Polo Club (1898; initially played on the Trabrennbahn, from 1907 on Jenischstrasse in Flottbek), the Workers Cyclists Club Ottensen (also 1898; as a member of the Workers Cyclists Association “Solidarity” part of the German workers' sports movement ) and the upper-class Hamburg Golf Club (1906; club's own facility also in Flottbek). On the northern periphery, near today's parcel post office on Kaltenkircher Platz, another, rapidly growing football club was founded with Union 03 Altona . In 1909 the Altona artist association was founded.

Since 1913 the magistrate has purposefully bought or leased private land in order to turn it into public green spaces ( Donners , Rathenau, Jenisch , Gayenscher and Volkspark with adjoining main cemetery) and, starting below Rainville , to build the continuous Elbe bank hiking trail to Schulau. On the occasion of the city's 250th anniversary, Altona hosted the German Horticultural Exhibition in 1914 - but this was overshadowed by the outbreak of the First World War .

1918 to 1945

After the First World War, the horticultural director Tutenberg laid out a recreational area near the city north of the Bahrenfeld trotting track with the Volkspark , initially 125 hectares in size; to this end, the urban “Central Cemetery”, an airfield (on Luruper Chaussee ) and the Altona stadium were built on the outskirts . Since the 1920s, Altona has been the German city with the most green spaces (see also below).

Under Mayor Max Brauer ( SPD , already 2nd Mayor since 1919), who was in office from 1924 to 1933 , the city experienced an upswing that is still visible in many places today, which in 1927 saw the doubling of the city area through the incorporation of the Elbe villages Groß- and Klein Flottbek , Nienstedten and Blankenese and Rissen and the Geest communities of Osdorf , Iserbrook , Sülldorf , Lurup , Eidelstedt and Stellingen-Langenfelde culminated. This step, which was by no means welcomed by all affected municipalities (see Lower Elbe Law ), was accompanied by a forward-looking urban development policy, which is particularly reflected in the general building plan (drawn up by Altona's Senator for Construction Gustav Oelsner as early as 1923 for Altona and other Prussian areas around Hamburg), the purchase of land under construction and the establishment of the municipal housing company Siedlungs-Aktiengesellschaft Altona (SAGA) (1922). For recreational purposes, three green belts were created through the city; also Hagenbeck Zoo in Stellingen was a Altona attraction.

In general, this was the high time of municipalization of supply services: the waterworks at Baurs Berg in Blankenese, the gasworks in Bahrenfeld, the electricity works Unterelbe (EWU) in Neumühlen (built in 1913; Siemens shares taken over in 1922) were owned by the city - and were sufficient for the needs of the growing city soon not enough: as early as 1928 a second power plant was connected to the grid in Schulau (today part of Wedel / Holstein). A municipal company, the Verkehrs-Aktiengesellschaft Altona ( VAGA ), was also founded in 1925 for the increasingly necessary local traffic development . In the same year, Europe's first regular seaplane route opened between Altona and Dresden .

Altona had developed into a veritable city with a population that had risen from 172,628 (1910) to 231,872 (1928). This made it the largest city in Schleswig-Holstein . However, the independence lasted just under eleven years.

At the end of the Weimar Republic , the "red Altona" also fought hard against National Socialist influences : the climax was the resistance of many residents against a propaganda march by Schleswig-Holstein SA organizations through the narrow, densely populated streets of Altona old town . This “ Altona Blood Sunday ” (July 17, 1932) led to the so-called “ Prussian Strike ”, ie the coup-like dismissal of the Prussian government led by Otto Braun (SPD) by the Reich government under Franz von Papen .

After the seizure of power of the NSDAP four men were for alleged crimes during the Bloody Sunday by a special court convicted and executed in the summer of 1933 Altona: Karl Wolff , Bruno Tesch , August Lütgens and Walter Möller . These names can also be found (since the late 1980s) on the Altona city map; and in the 1990s these injustice judgments were finally overturned.

In response to Bloody Sunday, 21 Altona pastors read the Altona Confession in January 1933 in the St. Trinity Church . It is considered an important document of church resistance against the Nazi dictatorship and one of the founding documents of the Confessing Church . Today, memorial plaques such as B. at the Petri Church of this event.

However, Altona was not spared from the decline of the Golden Twenties and the rise of fascism . The number of unemployed rose from 2,683 (December 1929) to 14,161 (May 1932). And in the election to the city council in 1929, the NSDAP local group founded in 1923 around Hinrich Lohse , Emil Brix and Paul Moder received only 6,880 votes (SPD 46,122, KPD 18,046), but in the Reichstag election in November 1932 , at the height of the World economic crisis , the National Socialists were only in second place in Altstadt (behind the KPD), Ottensen, Bahrenfeld and Lurup (behind the SPD), while they were particularly in Rissen, Sülldorf, Oevelgönne (over 50%), Blankenese and Othmarschen (over 40%) had their strongholds. On March 10, 1933 - two days before the local elections - the National Socialists occupied the Altona town hall one night and declared the deputy Gauleiter Emil Brix as the new mayor. Corresponding to the number of votes from March 12, 1933: NSDAP 60,112, SPD 32,484, KPD 17,501, battle front black-white-red 11,057.

The Nazi rule led to the persecution of those who think differently and the destruction of Jewish life in the city - in the mid-1920s around 2,400 people of Jewish faith or 1.3% of the resident population - which today are remembered by the following memorials , among others :

- the black cuboid Black Form - Dedicated to the Missing Jews by Sol LeWitt at the south end of the Platz der Republik

- the memorial stone at the edge of the station forecourt for the more than 800 Jews who on 28 October 1938 during the so-called " Poland action taken" from their homes and from the Altona station to Poland deported were

- the bronze plaque on the Kirchenstrasse 1 building in memory of the synagogue of the High German Israelite Congregation in Kleine Papagoyenstrasse

- the list of those buried in the built-up Jewish cemetery Ottensen in the basement of the Mercado shopping center .

Due to the Greater Hamburg Law , Altona became part of the State of Hamburg in 1937 and lost its status as an independent municipality through incorporation on April 1, 1938; the surprised residents of the city found out about it from the newspaper or the radio. In October of the same year, the district boundaries in Hamburg were changed in line with the district boundaries of the National Socialist party organization; As a result, Altona lost part of its historical area (especially to St. Pauli and Eimsbüttel) and was identical to the NSDAP party group 7. These changes were retained even after the end of the NSDAP dictatorship. Adolf Hitler had designated Hamburg as the “ Führerstadt ” and wanted to incorporate gigantic buildings into Altona's center and the Elbe slope with the Gauhochhaus, Volkshalle and a “Great Elbe High Bridge according to the Führer’s plans” ( Hamburger Tageblatt ). Except for preparatory measures, nothing of this typical architecture in National Socialism was realized if the airfield on Luruper Chaussee, which the Wehrmacht had converted into a "home defense" air base for the Luftwaffe (today as a green area and parking lot and mainly used by DESY ), is not part of the NS- Architecture matters.

The air raids in World War II Allied bombers during the "destroyed Operation Gomorrah " large parts of the Old City in July 1943 and transformed in particular the densely populated area between Nobistor and Allee , Holsten - and Grosse Elbstrasse in an extensive field of ruins; Altona's historic core around town hall and coin market was destroyed and later not rebuilt. Even north of Stresemannstrasse to the Eimsbüttel market square , entire streets were no longer recognizable. Of the Altona main church St. Trinitatis only the surrounding walls with the empty window cavities and the tower base remained annealed.

Reconstruction seemed impossible in the first few years after the war. The total demolition and the construction of a modern church was discussed, but in the 1950s the conviction prevailed that the traditional building of the Altona main church should be saved and rebuilt, albeit in a largely modern form. Altona's trading center, the fish market , was destroyed with the exception of a few houses and neglected until the 1970s.

After 1945

After the war, new streets were laid there (extension and widening of Holstenstrasse to Reeperbahn , Alsenstrasse to Fruchtallee ) or open spaces were created ( Neu-Altona green corridor ); instead of the small-scale, closed perimeter block development, individual high-rise buildings and blocks of houses were built ( new Altona plan ) to combat the housing shortage: because until around 1960 there were Nissenhütten settlements and other emergency accommodation in this quarter (e.g. behind Unzerstrasse and on Eggerstedtstrasse ).

In the following decades, the change continued: under the motto “Air and light for the working class”, space was redeveloped , around 1970 in Altona's former main business district around Große Bergstrasse , on Hexenberg or, most recently, in 1980 in the Behn'schen area City expansion.

The most spectacular example from the second half of the 1970s: the demolition of the cityscape-defining brick central train station and its replacement by a department store with a siding (vernacular: "Kaufbahnhof").

Some major projects were also prevented, e.g. For example, a motorway feeder through Ottensen, which was to be converted into the “City West” office district at the same time, or the demolition of the buildings of the old general hospital Altona an der Allee (today Max-Brauer-Allee).

In the mid-1960s, with the beginning of postmodernism, the preservation authorities pleaded for the restoration of the original shape of the Altona main church on the outside, but on the inside for a modern solution. The design of the entire artistic interior and the colors show a commitment to tradition, which was translated into the language of the 20th century using artistic means. In 1970, the reconstruction was awarded the Hamburg Architecture Prize as an exemplary building for the combination of old and new .

After the storm surge in 1976, the Altona architect Günter Talkenberg was commissioned to draw up a report for the coastal protection between St. Pauli and the former, decaying fish auction hall. Talkenberg insisted on an urban planning solution that included the fish market with a development on the edge of the square and demanded the preservation of the fish auction hall , which was built in the form of a three-aisled basilica . At that time, nobody could have imagined that a hall that had to be flooded during flooding could have any economic benefit. It was reopened for the II. Hamburg Building Forum and was awarded a diploma for European monument protection. From 1988 to 1994 the post-modern development of the Altona fish market with apartments of the Altonaer Spar- und Bauverein and the Bauverein der Elbgemeinden (BVE) was created .

In the 1990s, an ensemble of politically controversial solitary buildings (part of the "pearl necklace" on the edge of the Hamburg harbor) was built on the banks of the Elbe between Altonaer Fischmarkt and Neumühlen, which made the tertiaryisation of the economy visible in Altona's cityscape: the fish processing industry stepped forward mainly office complexes, restaurants and leisure facilities - and not just on the river: Reemtsma , British American Tobacco (BAT), Gartmanns chocolate factory , Holsatia wood processing , Margarine-Union and Essig-Kühne in Bahrenfeld, Zeise (ship propeller casting), Menck & Hambrock (excavator production ) or Aal-Friedrichs in Ottensen and the Elbschloss brewery in Nienstedten are among the large commercial employers who have given up or relocated their production facilities in the last few decades.

Politically, the post-war Altona was relatively heterogeneous due to its social mix of inner-city workers' and peripheral upper-class residential areas - with a trend towards decreasing social democratic dominance since the 1960s.

Altona includes some of Hamburg's richest districts, but also some of the lowest incomes: average income per taxpayer in 1998 in Othmarschen 81,149 euros with a welfare recipient share of 0.9%, in Altona old town 23,599 euros and 14.7%.

Since the beginning of the 1980s, due to the structural upgrading ( gentrification ) and the emergence of various milieus and subcultures , especially in Ottensen and Altona, new preferences had been added, which resulted, among other things, in green-alternative district election results of up to 22% (1997) expressed. Hamburg's first formal red-green coalition (1994–1997) as well as the first black-green cooperation (since 2004) came into being in Altona. At the same time, the share of immigrants fell from the once above average 17.4% (compared to 15.9% in the whole of Hamburg, 1998) to meanwhile Hamburg's level (13.6% each, 2010). Nevertheless, despite the arrival of new residents, a specific Altona self-image was strengthened, which is reflected in local patriotic groups such as the Altonaer Freiheit , which wants to bring Altona concerns more into the public eye of the Hamburg population.

On the occasion of the passage of a British submarine to Hamburg, the district assembly in 1983 declared the Altona district a nuclear-weapon-free zone .

Incorporations

The city of Altona became part of the new Altona district in the province of Schleswig-Holstein on September 26, 1867 . The villages of Neumühlen and Ottensen, from which the city of Ottensen was formed in 1871, also belonged to it. On April 1, 1889, the city of Ottensen was incorporated into the city of Altona, so that the Altona district only included the municipality of Altona.

On April 1, 1890, the rural communities of Bahrenfeld, Oevelgönne, Othmarschen and on July 1, 1927, the rural communities of Blankenese, Eidelstedt, Groß Flottbek, Klein Flottbek, Lurup, Nienstedten, Osdorf, Rissen, Stellingen-Langenfelde and Sülldorf became the district of Pinneberg City municipality or the urban district of Altona incorporated.

On January 1, 1934, the municipality of Altona was renamed the City of Altona, incorporated into the State of Hamburg on April 1, 1937 with the Greater Hamburg Act and into the Hanseatic City of Hamburg on April 1, 1938.

Population development

The following overview shows the population of the municipality of Altona (since 1884 a major city ) according to the respective territorial status. Up to 1789 these are mostly estimates, from 1803 census results . From 1843, the information relates to the “local population” and from 1925 to the resident population . Before 1843, the number of inhabitants was determined according to inconsistent survey methods. Altona has been part of the city of Hamburg since April 1, 1938. The population of the district since 1987 comes from the Hamburg district database of the statistical office for Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein.

|

|

|

|

politics

Citizenship

For the election to Hamburg citizenship , the Altona district is divided into the two constituencies of Altona and Blankenese .

District Assembly

In the 2019 district assembly election, the Greens became the strongest party ahead of the SPD for the first time with 35.1%. In addition, the CDU, Left, FDP and AfD are represented in the district assembly, whereby the AfD - as otherwise only in the Hamburg-Nord district - missed parliamentary group status with only two mandates.

badges and flags

Blazon : "In red over a blue shield base a silver (white) black jointed city gate with open gate wings and three hexagonal pointed towers with pointed helmets and pommel, the middle one slightly higher."

On August 23, 1664, Friedrich III. from Denmark to Altona and gave it a coat of arms. It shows a city gate by the water with an open gate, initially with an open portcullis , which was later left out. It should symbolize a cosmopolitan city on the Elbe. The colors red and silver stand for Holstein and blue for the Elbe . The coat of arms was last approved by the Prussian king in 1904 .

Description of the flag: "In the middle of the red flag is the coat of arms of the former city of Altona."

Today, the Altona district has an oval shield-shaped sign derived from the original coat of arms (with portcullis).

Culture and sights

Squares and buildings

Altona defines itself through more than the Elbe, Ottensen and the proximity to the Reeperbahn. One of the main attractions is the fish market which is frequented by tourists and locals. The restored fish auction hall is also worth seeing . The Elbe section between the fish market and Övelgönne is popular for all kinds of activities.

From the banks of the Elbe at the confluence of Carsten-Rehder- and Große Elbstraße , the Köhlbrandt staircase, inaugurated in 1887, can be seen with its monumental head structure: until the 1960s, thousands of workers used this facility every day on their way between the densely built-up residential areas in the upper town and the ferry terminal or the port and commercial operations on the banks of the Elbe. On the water side of this road junction is the Holzhafen , which is also the oldest preserved (although no longer used) basin in the entire Hamburg port area , built in 1722 .

The Elbchaussee (first section: Klopstockstraße ) begins at the Altona town hall , which is located in the entrance building of the first Altona train station , and stretches westward above the Elbe slope to Blankenese . Also at the town hall, directly on the Elbe slope, the Altona balcony , a vantage point with a wide view of the harbor. This is also where the Elbe bank hiking trail begins , on which you can always hike along the water towards Övelgönne and Blankenese to Wedel or - on a section of the Elbe cycle path - cycle. At the Neumühlen pier, a private association in the museum harbor Oevelgönne has assembled a large number of historic ships, which its members also restore themselves.

Altona's most important symbol, the Stuhlmannbrunnen, inaugurated in 1900, lies between the town hall, the Altona Museum and the new train station : two centaurs are wrestling over a huge fish - an allegory of the competition between the neighboring cities of Altona and Hamburg. A few steps away on Schillerstraße is the neo-Gothic St. Petri Church by Johannes Otzen .

From the St. Pauli landing stages there are ferry connections on the Elbe along the Altonaer Ufer to Finkenwerder , to the museum harbor Oevelgönne and to Blankenese with a view of the numerous villas on the Elbe slope. Altona itself still has five quays for Elbe ferries (to be used with HVV tickets): Altona Fischmarkt (at the fish auction hall ), Dockland (fishing port), Neumühlen / Övelgönne, Teufelsbrück and Blankenese.

The builders who shape the cityscape include in particular

- Christian Frederik Hansen (1756–1845), who between 1789 and 1806, as a Holstein country master builder, created various upper-class residential and country houses, but also public buildings in Altona, Ottensen and the Elbe villages, for example the "Elbschlösschen", the stable building "Halbmond" “White House” (all on Elbchaussee ), the “Palais Baur ” Palmaille 49 and the town houses Palmaille 108–120.

- Gustav Oelsner (1879–1956), the building senator in Altona (1924–1933), the urban apartment building - for example the apartment blocks at Lunapark ( Altona-Nord ) and Bunsenstraße ( Ottensen ) - but also the garden city Steenkampsiedlung ( Bahrenfeld ) and functional buildings (Kaischuppen) E / F in Neumühlen, employment office in Altona-Nord).

The factory (Ottensen, Barnerstrasse) is still an atmospherically “dense” venue for rock concerts .

Parks and nature reserves

- Altonaer Volkspark in Bahrenfeld

- Jenisch Park with the Flottbektal nature reserve in Hamburg-Othmarschen

- Loki Schmidt Garden in Hamburg-Osdorf

- various parks on the Elbe slope, especially in Blankenese

- Schnaakenmoor nature reserve and

- Wittenbergen nature reserve in Rissen

Regular events

The following major events take place annually in Altona:

- The altonale , a 14-day cultural festival in June in the entire Altona center with art, literature and theater as well as a huge street festival on the final weekend with eight to ten live music stages

- The Cyclassics , a cycling event with amateur and professional races , both of which lead in a large loop through the district (August)

- The Hamburg Marathon runs through Altona on part of its route at the end of April

Economy and Infrastructure

Public facilities

- schools

- 29 state primary schools and 9 independent primary schools (as of 2011)

- 6 special schools (as of 2011)

- 7 district schools (as of 2017)

- 11 state grammar schools and 1 independent grammar school (as of 2017)

- Theatre:

- Altona Theater ,

- Avenue theater ,

- New flora ,

- Theater in the basilica ,

- monsoon theater in Friedensallee,

- Thalia on Gaußstrasse

- " Factory "

- District cultural centers:

- "HausDrei" on the site of the former Altona General Hospital on Max-Brauer-Allee,

- "Motte" in Ottensen

- "GWA / Kölibri" in St. Pauli-Süd

Transport links

The Hamburg-Altona station was for decades an important railway junction of the German rail passenger intercourse . It is the end and starting point for numerous rail connections from and to the south and with Scandinavia .

With the A 7 motorway ( E 45 ; exits HH-Othmarschen, -Bahrenfeld and -Volkspark) an important European north-south connection and with the B 4 a large national north-south road connection lead directly through the district. In addition, the B 431 crosses the district in an east-west direction.

The inner development and the connection with other Hamburg districts through the local public transport within the framework of the Hamburger Verkehrsverbund are provided in particular by the S-Bahn lines S1, S11, S2, S21, S3 and S31, numerous bus lines of the Hamburg-Holstein transport company (VHH) and the Hamburger Hochbahn (HHA) as well as some Elbe ferries from HADAG Seetouristik und Fährdienst .

In addition, the district is crossed by the long-distance cycle routes Hamburg-Bremen , the Elbe cycle path , the North Sea coast cycle path and the Nordheide cycle path . Inner-city bike routes are also being planned or implemented, for example from the Altona train station to the university and from the Elbe suburbs via Ottensen to St. Pauli.

Since 2018 there has been a diesel driving ban for vehicles with emission standards five and worse on the streets of Max-Brauer-Allee and Stresemannstraße in the district .

Personalities

Honorary citizen

According to the year of appointment:

- 1872: Gustav von Manstein (1805–1877), General of the Infantry

- 1891: Franz Adickes (1846–1915), mayor

- 1895: Otto von Bismarck (1815–1898), Reich Chancellor

- 1895: Hermann von Tresckow (1818–1900), General

- 1896: Alfred Graf von Waldersee (1832–1904), Field Marshal General (a)

- 1908: Ferdinand Rosenhagen (1830–1920), 2nd mayor

- 1937: Hinrich Lohse (1896–1964), Gauleiter of Schleswig-Holstein (b)

Sons and Daughters of Altona

- Conrad von Höveln (* 1630; † 1689 in Brandholm, Vejle County, Denmark), Baroque poet

- Fromet Mendelssohn , b. Gugenheim (* 1737; † 1812 in Altona), businesswoman and wife of the philosopher Moses Mendelssohn

- Lorenz Levin Salomon Fürst (* 1763; † 1849), businessman and plaintiff for equality before the Reich Chamber of Commerce

- Erhard Adolf Matthiessen (* 1763; † 1831 in Altona) lawyer, businessman and councilor

- Gustav Ludwig Baden (* 1764; † August 25, 1840 in Copenhagen), historian and notary

- Johann Carl Julius Herzbruch (* 1779; † 1866 in Glückstadt ), Evangelical Lutheran clergyman; from 1835 to 1855 general superintendent for Holstein

- Christopher Ernst Friedrich Weyse (* 1774; † 1842 in Copenhagen), composer

- Conrad Hinrich Donner (* 1774; † 1854 in Altona, grave in the Heilig-Geist-Kirchhof ), merchant

- Friedrich Georg Wilhelm Struve (* 1793; † 1864 near St. Petersburg), astronomer

- Ernst Meyer (* 1797; † 1861 in Rome), German-Danish painter

- Günther Ludwig Stuhlmann (* 1797; † 1872 in Nice), manufacturer and patron

- Oskar Ludwig Bernhard Wolff (* 1799; † 1851 in Jena), writer

- Siegfried Dehn (* 1799; † 1858 in Berlin), music theorist and composition teacher

- Karl Ferdinand Theodor Hepp (* 1800; † 1851 in Tübingen), legal scholar and university professor

- Otto Friedrich Kruse (* 1801; † 1880 in Altona), teacher for the deaf and dumb

- Ludolf Wienbarg (* 1802; † 1872 in Schleswig), writer of the Vormärz

- Gottfried Semper (* 1803; † 1879 in Rome), master builder

- Johann Otto Donner (* 1808; † 1873 in Altona), ship commander and rear admiral of the Prussian Navy

- Albert Peter Johann Krüger (* 1810; † 1883 in Hamburg), actor, journalist and writer

- Cornelius Gurlitt (* 1820; † 1901 in Altona), composer

- Wilhelm Kümpel (* 1822; † 1880 in London), painter

- Carl Reinecke (* 1824; † 1910 in Leipzig), composer

- Johann August Roderich von Stintzing (* 1825; † 1883 in Oberstdorf), lawyer and legal historian

- Eugen Krüger (* 1832; † 1876 in Düsternbrook), lithographer and painter

- August Sonntag (* 1832; † 1860 in Greenland), astronomer and polar explorer

- Emil Warburg (* 1846; † 1931 in Grunau, today Bayreuth), physicist

- Johann Heinrich Kaspar Gerdau (* 1849; † 1917 in Porto Alegre, Brazil), entrepreneur

- Alexander Baur (* 1857; † 1909 in Altona), Senator of the city of Altona

- Constantin Brunner , actually Leo Wertheimer (* 1862, † 1937 in The Hague), philosopher

- Franz Hein (* 1863; † 1927 in Leipzig), painter and poet

- FCS Schiller (* 1864; † 1937 in Los Angeles), philosopher

- Alfred Henke (* 1868; † 1946 in Wannefeld), German politician (SPD / USPD), MdR , 1919 Chairman of the Council of People's Representatives in Bremen

- Heinrich von Bünau (1873–1943), Prussian infantry general

- Moses Levi (* 1873; † 1938 in Hamburg-Altona), German lawyer

- August Trümper (* 1874; † 1956 in Oberhausen), painter

- Bertha Dörflein-Kahlke (* 1875; † 1964 in Felde near Kiel), German painter

- Otto Kähler (* 1875; † 1955 in Itzehoe) German lawyer, notary and legal historian

- Hans Piper (* 1877; † 1915), physiologist in Berlin

- Harald Bredow (* 1878; † 1934), actor and screenwriter

- August Kirch (* 1879; † 1959 in Hamburg-Altona), SPD Senator 1918–1933, District Office Manager 1945–1954

- Fritz Meyer (* 1881; † 1953 in Konstanz), businessman and NSDAP politician

- Heinrich Deiters (* 1882; † 1971 in Hamburg), freelance writer and journalist

- Georg Warnecke (* 1883; † 1962 in Hamburg), lawyer and entomologist

- Hans Ehrenberg (* 1883; † 1958 in Heidelberg), theologian

- Wilhelm Heinitz (* 1883; † 1963 in Hamburg), musicologist

- Louise Schroeder (* 1887, † 1957 in Berlin), MdR , MP , Mayor of Berlin

- Max Brauer (* 1887; † 1973 in Hamburg), Lord Mayor of Altona, 1st Mayor of Hamburg

- Hans Friedrich Blunck (* 1888; † 1961 in Hamburg), writer, President of the Reich Chamber of Literature

- Henning Brütt (* 1888; † 1979 in Hamburg), surgeon, medical director of the port hospital

- Adolf Jäger (* 1889; † 1944 in Hamburg-Altona), football player

- Carl FW Borgward (* 1890; † 1963 in Bremen), automobile manufacturer, founder of the Borgward works

- Richard Spethmann (* 1891; † 1960 in Schwerin), theater actor, director, theater director and Low German writer

- Claus Wenskus (* 1891; † 1966), painter

- Wilhelm von Allwörden (* 1892; † 1955 in Hamburg), National Socialist politician and Hamburg Senator

- Axel Werner Kühl (* 1893; † 1944 in Verden), pastor at the Jakobikirche (Lübeck)

- Alfred Toepfer (* 1894; † 1993 in Hamburg), entrepreneur and patron

- Walter Göttsch (* 1896; † 1918 at Amiens / F), fighter pilot in the First World War

- Ernst Johannsen (* 1898; † 1977 in Hamburg), writer

- Wilhelm Roloff (* 1900, † 1979 in Canada), manager and resistance fighter

- Edgar Ende (* 1901; † 1965 in Netterndorf near Munich), painter

- Heinrich Gau (* 1903; † 1965), Mayor of Wedel

- Rudolf Beiswanger (* 1903; † 1984 in Hamburg), director of the Ohnsorg Theater

- Willy Dehnkamp (* 1903; † 1985 in Bremen), Reichsbanner functionary, resistance fighter and President of the Bremen Senate

- Georg Dahm (* 1904; † 1963 in Kiel), criminal and international law specialist

- Heinrich Christian Meier (* 1905; † 1987 in Hamburg), writer, artist and astrologer

- Anita Felguth (* 1909; † 2003 in Berlin), table tennis national player

- Wera Liessem (* 1909; † 1991), actress and dramaturge

- Alfred Petersen (* 1909; † 2004 in Schleswig), Protestant theologian

- Karin Hardt (* 1910; † 1992 in Berlin), actress

- Oswald Hauser (* 1910; † 1987 in Kiel), historian

- Adolf Ruppelt (* 1912; † 1988 in Hamburg), Lutheran clergyman

- Axel Springer (* 1912; † 1985 in Berlin), publisher

- Hans Wentzel (* 1913; † 1975 in Stuttgart), art historian

- Margret Bechler (* 1914; † 2002 in Wedel), officer's wife and teacher

- Heinz-Joachim Heydorn (* 1916; † 1974 in Frankfurt am Main), educator

- Heinz Lanker (* 1916; † 1978 in Hamburg), actor at the Ohnsorg Theater

- Heinz bung bottle (* 1919; † 1972 in Hamburg-Altona), football player

- Karlheinz Bargholz (* 1920; † 2015 in Hamburg), architect

- Ruth Stephan (* 1925; † 1975 in Berlin), film and stage actress

- Jürgen Oldenburg (* 1926; † 1991), politician (SPD)

- Günter Lüdke (* 1930; † 2011 in Hamburg), actor

- Werner Erb (* 1932; † 2017), football player

- Uwe Friedrichsen (* 1934; † 2016 in Hamburg), actor, audio book and voice actor

- Gisela Werler (* 1934; † 2003 in Hamburg) is Germany's first female bank robber

- Jens Lausen (* 1937; † 2017 in Hamburg-Bergedorf), German painter and graphic artist of the "New Landscape"

- Eddy C. Bertin (* 1944; † 2018), Belgian author of horror, science fiction and youth literature

- Fatih Akin (* 1973), film director

- Adam Bousdoukos (born 1974), actor

- Christian Rahn (* 1979), soccer player

- Leon Rohde (* 1995), track cyclist

Other personalities

Other personalities who were not born in Altona but had a lasting effect in the city and were buried there:

- Eustasius Friedrich Schütze (1688–1758), Protestant theologian (died in Altona)

- Georg Christian Maternus de Cilano (1696–1773), born in Pressburg ; City physician, professor, counselor and librarian in Altona (died in Altona, grave site unknown)

- Johann Peter Kohl (1698–1778), born in Kiel , theologian and polymath (died in Altona, grave site unknown)

- Johann Michael Ladensack (* 1724 in Merseburg; † August 10, 1790 in Altona), spiritualist

- Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock (1724–1803), poet (burial place in the Christian church yard in Ottensen)

- Friedrich Konrad Lange (1738–1791), rector of the Christianeum and provost

- Heinrich Wilhelm Lawätz (1748–1825), playwright, poet, syndic of the Uetersen monastery and judiciary (died in Altona)

- Conrad Daniel Graf von Blücher-Altona (1764–1845), Upper President (burial site at the Norderreihe cemetery )

- Heinrich Christian Schumacher (1780–1850), astronomer and geodesist (burial place in the Heilig-Geist-Kirchhof in Altona-Altstadt)

- Salomon Ludwig Steinheim (1789–1866), doctor, religious philosopher and scholar (destroyed grave site in the Jewish cemetery on Königstrasse )

- Caspar Arnold Engel (1798–1863), politician and member of parliament for Altona in the Frankfurt National Assembly (died in Altona)

- Carl Nicolaus Kähler (1804–1871), educator, Evangelical Lutheran pastor (most recently a. St. Trinity), theologian and local researcher (died in Altona)

- Matthäus Friedrich Chemnitz (1815–1870), lawyer and poet (burial place in the Norderreihe cemetery )

- Helene Donner (1819–1909), founded the Helenenstift , died in Neumühlen

- Sophie Wörishöffer (1838–1890), writer and author of young books, known as Karl May von Altona (died in Altona)

- Gregor Clemens Kähler (1841–1912), Evangelical Lutheran pastor (1873–1912 ad Christianskirche), theologian and church historian (died in Altona)

- Charlotte Niese (1854–1935), poet (burial place in the Bernadottestrasse cemetery in Ottensen)

- Felix Woyrsch (1860–1944), composer and city music director (grave at the Bernadottestrasse cemetery in Ottensen)

- Hans Meyer, architect of the Altona Seafaring School on Rainvilleterrasse . In addition to Gustav Markmann, the in-house architect of the Altonaer Spar- und Bauverein was involved in the Woyrschweg residential complex (1905–1912) and then had the Stresemannstrasse, Schützenstrasse, Leverkusenstrasse and Leverkusenstieg (1913–1928) and Bahrenfelder Chaussee, Bornkampsweg (1928–1931) residential complexes. planned.

- Herbert Tobias (1924–1982), photographer (grave at the main cemetery in Altona , honorary grave )

- Peter Rühmkorf (1929–2008), writer, lived in Ottensen, later in Övelgönne (grave at the Altona main cemetery )

See also

- Altona Mayor

- Altona furnace

- List of cultural monuments in the Hamburg district of Altona

- Altona artists' association

literature

- Olaf Bartels : Altonaer Architects - A city building history in biographies . Junius, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-88506-269-0 .

- Hajo Brandenburg: Hamburg-Altona . Sutton, Erfurt 2003, ISBN 3-89702-556-6 .

- Ottensen Chronicle . Edited by Förderkreis e. V., Hamburg 1994.

- Richard Ehrenberg: Altona under the rule of Schauenburg . Altona 1893.

- Hans-Günther Freitag, Hans-Werner Engels: Altona - Hamburg's beautiful sister . A. Springer, Hamburg 1982. (Christians, Hamburg 1991, ISBN 3-7672-1135-1 )

- Torkild Hinrichsen : On Danish tracks in the old town of Altona . Publishing group Husum, Husum 2014, ISBN 978-3-89876-758-3 .

- Paul Th. Hoffmann: Neues Altona 1919–1929 . 2 volumes. E. Diederichs, Jena 1929.

- Manfred Jessen-Klingenberg : From Denmark to Hamburg. On the history of Altona . In: From the history of Altona and the Elbe suburbs (= writings on politics and history in Hamburg . No. 3 ). Hamburg 1990, p. 24-42 .

- Anthony McElligott: The "Abruzzenviertel" - Workers in Altona 1918-1932. In: Herzig, Langewiesche, Sywottek: Workers in Hamburg . Education and Science, Hamburg 1983, ISBN 3-8103-0807-2 .

- Anthony McElligott: Contested City. Municipal Politics and the Rise of Nazism in Altona, 1917–1937 . University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor 1998, ISBN 0-472-10929-4 .

- Hans-Kai Möller: Altona-Ottensen: Blue haze and red flags. In: Urs Diederichs: Schleswig-Holstein's way into the industrial age . Christians, Hamburg 1986, ISBN 3-7672-0965-9 .

- Holmer Stahncke: Altona. History of a city . Ellert & Richter, Hamburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-8319-0560-7 .

- Wolfgang Stolze: Branch lines of the ruling house of Oldenburg in Denmark and their "duchies". In: The home. Journal for natural and regional studies in Schleswig-Holstein and Hamburg. Husum 110.2003, H. 3/4, pp. 49-63. ISSN 0017-9701

- Helmuth Thomsen: Hamburg-Altona. In: Olaf Klose (Hrsg.): Handbook of the historical sites of Germany . Volume 1: Schleswig-Holstein and Hamburg (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 271). 3rd, improved edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1976, ISBN 3-520-27103-6 , pp. 93-95.

- Christoph Timm: Altona old town and north . Monument topography. Christians, Hamburg 1987, ISBN 3-7672-9997-6 .

- Stefan Winkle: Johann Friedrich Struensee - doctor, enlightener, statesman. 2nd Edition. G. Fischer, Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 3-437-11262-7 .

Web links

- Website of the district office of Altona

- Altona on an Orfix city map from 1928 ( Memento from October 20, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- Say about the creation of Altona: "Dat is ja all to na!"

- Initiative for the preservation of the Altonaer Volkspark

- Altona City Archives (private association)

Individual evidence

- ^ Regional data for Altona , Statistical Office for Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein

- ↑ § 1 District Administration Act (BezVG) of July 6, 2006 . In: HmbGVBl . Part I, No. 33 , 2006, pp. 404 ( landesrecht-hamburg.de [accessed on March 18, 2018]).

- ^ Order on the division of the area of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg . In: HmbGVBl . Part II, Official Gazette, No. 181 , September 7, 1965, pp. 999 .

- ^ Helmuth Thomsen: Hamburg-Altona (lit.), p. 93. Identical names with Altena .

- ^ Horst Beckershaus: The names of the Hamburg districts. Where do they come from and what they mean , Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-434-52545-9 , p. 12.

- ^ Result of the 1925 census; see Statistical Office of the City of Altona (ed.): The population census in Altona on June 16, 1925. Chr. Adolf, Altona-Ottensen 1927, p. 29.

- ^ City district archive Ottensen: Urban planning redevelopment in the 1970s

- ^ Official Journal of the Government in Schleswig 1871, p. 309 digitized

- ^ The communities and manor districts of the province of Schleswig-Holstein and their population. Edited and compiled by the Royal Statistical Bureau from the original materials of the general census of December 1, 1871. In: Königliches Statistisches Bureau (Hrsg.): The communities and manor districts of the Prussian state and their population. tape VII , 1874, ZDB -ID 1467441-5 , p. 108 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Altona district. In: territorial.de. Retrieved July 13, 2017 .

- ↑ Time series for Altona , regional results at www.statistik-nord.de

- ↑ The Altona coat of arms. (PDF) (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on August 26, 2014 ; accessed on August 24, 2014 .

- ^ Flag of Altona. Retrieved August 24, 2014 .

- ↑ www.altonale.de

- ↑ a b c Directory of schools in the Hamburg-Altona district (PDF; 1.6 MB)

- ↑ a b The secondary schools in Altona ( Memento from August 12, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) on hamburg.de, accessed on August 11, 2017