Confessing Church

The Confessing Church (BK) was an opposition movement of Protestant Christians against attempts to bring the teaching and organization of the German Evangelical Church (DEK) into line with National Socialism . Such attempts were made by the German Christians until 1934 , then state-appointed church committees and, in some cases, direct state commissioners who deposed the church representatives.

The BK reacted to this by delimiting its teaching, organization and training, and later also with political protests ( church struggle ). Since its foundation in May 1934, it has claimed to be the only legitimate church, and since October 1934 has created its own management and administrative structures with an ecclesiastical “emergency law”. Many of their pastors remained servants of the respective regional church (especially in Württemberg, Bavaria and Hanover). The BK did not form a unified opposition to the Nazi regime; Large parts of the professing Christians also remained loyal to the “ Führer state ” and also affirmed the Second World War .

overview

The starting point for the formation of an internal church opposition to German-Christian and state efforts to achieve conformity was the church policy of the Nazi regime. This followed the totality claim of the National Socialist ideology . Since it was founded , the NSDAP has pursued a double strategy: its program declared “positive Christianity” on the one hand to be the popular religion of all Germans in order to take over Christians, and on the other hand, subordinated it to racism and nationalism . Parts of the NSDAP sought a long-term dissolution and replacement of Christianity by neo-paganism ( neo-Paganism ).

The Confessing Church came into being because the Nazi regime had direct influence on the internal structure of the church after it " seized power ". These attacks by the state took place in three clearly different phases:

- Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler took sides with the German Christians in the church elections that were imposed on July 23, 1933, in order to use their majority to bring the regional churches into line with themselves,

- Formation of state-appointed "church committees" after the failure of the German Christians in order to keep the now divided Evangelical Church under state control (1935–1937),

- direct suppression from 1937 (training ban, arrest of leading members, drawing their pastors for military service, control of salary payments for BK pastors, publication bans) and exemplary organized disempowerment (association law in the Warthegau with the aim of "atrophying" church influence on society).

The BK was founded in accordance with this state church policy

- with a delimitation of their doctrine from all political ideologies and state claims to totality ( Barmer Theological Declaration May 1934)

- with its own organization that refused to cooperate with state control bodies (Second Confessional Synod of Dahlem, October 1934)

- with direct petitions and protests against state politics, not only concerning the church, by organs and leading representatives of the BK.

The consequences, from protest to common resistance against the Nazi regime , which should have followed from the clash between the church's creed and the totalitarian Nazi state ideology, did not materialize.

Some of the theologians and pastors in the BK, such as Walter Künneth and Rudolf Homann, represented a depoliticized church struggle and limited themselves in their writings to giving Protestant “answers” to the anti-church ideological attacks in Alfred Rosenberg's “ The Myth of the 20th Century ” - in “defense” of the “ethnic religion” and church of a National Socialist “neo-paganism” propagated by Rosenberg, whose anti-Semitic orientation and implementation in the National Socialist state they were on the other hand prepared to affirm.

The motto of the Confessing Church was Teneo, quia teneor - "I hold because I am held".

history

In response to the takeover of the state Aryan paragraph , the baptized Jews as "non- aryan should be" expelled from the Protestant Church, founded some Berlin pastor, including Martin Niemoller and Dietrich Bonhoeffer , in September 1933 the Pastors . He explained the incompatibility of the church's Aryan paragraph with the Christian creed and organized help for those affected. With this he became a forerunner of the Confessing Church with other groups like the Young Reformation Movement .

At the hour of birth of the Confessing Church , the self-proclamation of the confessional communities gathered in Ulm "as legitimate Protestant Church in Germany" , which was included in the Ulm Declaration of April 22, 1934 at the suggestion of Hans Asmussen .

This self-predication was taken up at the first Confessional Synod from May 29 to 31, 1934 in Wuppertal- Barmen ; there she adopted the “Barmen Theological Declaration” as her theological foundation. The declaration placed Jesus Christ as the only ground of faith of the church against foreign criteria and authorities and thus also rejected the state's claim to totality and the appropriation of the gospel for irrelevant political purposes. This debate about the true faith within the Church and to its relationship with the state policy in the "Third Reich" is called the church struggle .

After this synod, many so-called confessional congregations were formed, led by fraternal councils . They rejected the official church leadership and thus also turned against the National Socialist state, which, according to thesis 5 of the Barmer Declaration, was denied the claim "to become the only and total order of human life and thus also the determination of the church. fulfill". Initially, this resistance was hardly or not at all politically justified, but was directed against the church leaderships dominated by the German Christians.

At the second Reich Confessional Synod, on October 19 and 20, 1934 in Berlin-Dahlem, the Confession Synod passed the “ Dahlem Emergency Law ” and proclaimed the Reich Brotherhood Council as the legitimate leadership of the church, while the official church authorities no longer had any authority. At the instigation of the intact churches , he was assigned a provisional church leadership in November, which remained in office until February 1936. The theological justification was very similar between the Reformed or United Christians on the one hand and the Lutheran Christians on the other, but not identical in all details. For the Lutherans, it was the status of confession or status confessionis enshrined in the Evangelical Lutheran Church , which is given when church superiors distance themselves from the Lutheran confession - recorded in the Augsburg Confession . The Lutheran synodals saw this as given in the theology of the German Christians of the “ orders of creation ”, to which this nation , race and state belonged.

The claim of the opposition pastors was proclaimed in the empire on some so-called "confession days". In Frankfurt am Main alone , 12,000 people took part in the Confession Day, on which the State Brotherhood Council formed at the end of October 1934 raised the claim to be the legal leader of the Nassau-Hessen Church; 140 pastors of the regional church disobeyed their National Socialist bishop. By the end of September 1934, of the total of 800 clergy members of the Nassau-Hessen regional church, 361 serving and a further 90 not yet ordained vicars, i.e. more than half, had joined the Confessing Church.

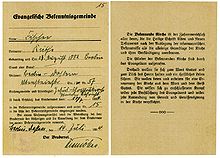

Within the Evangelical Church there were parishes and pastors who belonged to the Confessing Church, and there were confessional splits from parishes whose pastors had turned to the German Christians with some of the parishioners. Here prospective pastors (vicars and at that time still so-called auxiliary preachers) functioned illegally and alongside the church structures, without remuneration or only remunerated from donations, as preachers; For church services, emergency churches were set up in restaurants and, when this was banned, in factories and sheds. After the time of National Socialism, the Protestant Church only partially legalized these informal employment relationships: the period of service was taken into account, but no salary was paid.

At the end of 1935, Elisabeth Schmitz distributed her memorandum on the situation of German non-Aryans on the daily persecution of Jews in the Nazi state to 200 members of the Confessing Church, including Karl Barth , Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Helmut Gollwitzer . For security reasons she appealed anonymously to the responsible forces of the Confessing Church to provide assistance to the persecuted.

The next Confessional Synod took place in Bad Oeynhausen from February 18 to 22, 1936 , at which the second provisional church leadership was elected. Meanwhile, the Confessing Church had but divided into two wings, the temperate, the cooperation with the appointed in September 1935 new " Reich Minister for Church Affairs " Hanns Kerrl advocated in the new Reich Church Committee, and the radical wing, who refused it. A secret memorandum from the Confessing Church to Hitler from May 1936 described the existence of the concentration camps as the hardest burden on the evangelical conscience, but was never published by the Confessing Church. After the memorandum became known abroad, there were isolated arrests of clergymen, but the majority of the Confessing Church immediately abandoned the memorandum and even the subsequent discontinuation on some pulpits by more determined representatives of the Confessing Church left the decisive political passages in the memorandum not only dealt with Christians, away. With the Grüber office, too , the church supported people who were persecuted as Jews only to the extent that they had converted to Christianity or were of converts.

After initial success, the Confessing Church was increasingly persecuted from around 1937 onwards, but stuck to its own organization. Nevertheless, contrary to the self-portrayal of many of its members, it was not an opposition to National Socialism as such after 1945. However , the Confessing Church was recognized by the Allied Control Council as an "active anti-fascist resistance movement".

Martin Niemöller summarized what happened in 1976 as follows:

“When the Nazis brought the Communists in, I was silent; I wasn't a communist.

When they locked up the Social Democrats, I was silent; I wasn't a social democrat.

When they called the unionists, I was silent; I wasn't a trade unionist.

When they got me, there was no one left to protest. "

He describes his guilt and that of the church with the words: "We have not yet felt obliged to say anything for people outside the church ... we were not yet so far that we knew we were responsible for our people."

Hermann Maas , pupil and student in Heidelberg, among others, from 1915 pastor at the Heiliggeistkirche in Heidelberg, joined the association for the defense of anti-Semitism in 1932 . He was a member of the Confessing Church and Pastors he engaged since 1933/1934. In 1938 he was the head of the “Church Aid Office for Protestant Non-Aryans” in the city area, also helped all those persecuted for racism and worked closely with the Grüber office in Berlin . With his international contacts, he helped many people classified as Jews or half-Jews to escape until the beginning of the war. Despite being banned from his profession in 1933, he preached against the inhuman policies of National Socialism. In 1943, under pressure from the Nazi regime, he was removed from office by the Baden Evangelical Church Council. He was later deported to France for forced labor. After the liberation in 1945 he resumed his work as a pastor. With his thinking and, above all, his actions, he himself - as a member of the Confessing Church - is described as an isolated case and a notable exception. In 1950 he was Israel's first official German state guest.

Influence of the BK on the EKD after 1945

Leading members of the BK campaigned in October 1945 to ensure that the Stuttgart confession of guilt came about.

Some representatives of the Confessing Church played an important role in the re-establishment of the Evangelical Church in Germany from 1945. Its founding manifesto, the “Barmer Theological Declaration”, was included in the confessional documents of many Protestant regional churches. However, the synodal democracy practiced in the church struggle only made a limited impact in the church constitutions.

Members

Murdered and those who died from imprisonment

In 1949, the EKD's Brotherhood Council, as the successor to the BKD's Brotherhood Council, published a book of martyrs listing the BK members who were murdered and who perished in the concentration camps and their exact circumstances of death, as far as known. The book listed as "martyrs" by date of death:

|

|

|

The particularly well-known victims Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Friedrich Weißler, however, were never accepted into the intercessionists of the Confessing Church during the time of National Socialism, because they had acted politically from the point of view of the Church and the Confessing Church had always attached great importance to not offering any political resistance .

The introduction to the book of martyrs also emphasized:

"Everyone who is mentioned in this book ... did not take on their suffering because they did not agree with the politics of the Third Reich and recognized it as a fate for our people, but only ... because they did Confession of the Church saw attacked and it was also the commitment of life to maintain faithfulness to Christ's sake. "

The church struggle historian Hans Prolingheuer emphasized that this view depoliticized the confession of Christ, which for some of the confessors had political significance and helped determine the form of expression of their protest. The book omitted some of the members of the BK who were murdered as political resistance fighters of July 20, 1944 , conscientious objectors , “ disruptors of military strength ” or Jews . Werner Oehme, a pastor in the GDR, collected these names in 1979:

|

|

|

SS members

The BK never stated that loyalty to the confession was incompatible with service in the SS or in the concentration camp . A few BK members were temporarily in the SS at the same time:

- Kurt Gerstein applied to the SS to prevent the crimes in the extermination camps, at the "fiery furnace of evil" - according to his own declaration after the war.

- Hans Friedrich Lenz served in the Hersbruck subcamp near Flossenbürg , where Bonhoeffer was murdered. He later wrote an experience report.

- Alfred Salomon was smuggled into the SS in 1933/1934.

See also

- Members of the Confessing Church (WP category)

- Confessing Church in Schleswig-Holstein

- Evangelical weeks

- Publication series Confessing Church

- Series Breklum books

- Series of publications Theological Existence Today

- Young Church magazine

literature

- Kurt Dietrich Schmidt (ed. And introduction): The confessions and fundamental statements on the church question in 1933. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1934, DNB 368146812 .

- Friedrich Baumgärtel : Against the church battle legends. 2nd Edition. Freimund-Verlag, Neuendettelsau 1959; Reprinted 1976, ISBN 3-7726-0076-X .

- Joachim Konrad : As the last city dean of Wroclaw. Chronic review. Verlag Unser Weg, Ulm 1963, DNB 452530636 .

- Hugo Linck : The church struggle in East Prussia: 1933 to 1945. History and documentation. Gräfe and Unzer, Munich 1968, DNB 457435704 .

- Joachim Beckmann (Ed.): Church yearbook for the Protestant churches in Germany 1933-1944 . 2nd Edition. 1976, DNB 365198633 .

- Manfred Koschorke (ed.): History of the Confessing Church in East Prussia 1933–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1976, ISBN 3-525-55355-2 .

- Kurt Meier : The Protestant Church Struggle , three volumes. VEB Niemeyer, Halle (Saale) 1976–1984, DNB 550151532 . Licensed edition Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen, 1976–1984, DNB 550193464 .

-

The churches and the Third Reich

- Volume 1: Klaus Scholder : Prehistory and Time of Illusions, 1918–1934. Propylaen, Berlin 1977, ISBN 3-550-07339-9 ;

- Volume 2: Klaus Scholder: The year of disillusionment 1934. Siedler, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-88680-139-X ;

- Volume 3: Gerhard Besier : Divisions and defensive battles 1934–1937. Propylaea, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-549-07149-3 .

- Werner Oehme: Martyrs of Protestant Christianity 1933–1945. Twenty-nine life pictures. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1979, DNB 800224825 ; 3rd edition: 1985, DNB 850776171 .

- Jørgen Glenthøj: The oath crisis in the Confessing Church 1938 and Dietrich Bonhoeffer. In: Journal for Church History, Vol. 96 (1985), Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1985, pp. 377-394.

- Gerhard Besier: Approaches to political resistance in the Confessing Church. In: Jürgen Schmädeke, Peter Steinbach (ed.): The resistance against National Socialism. Munich 1986, ISBN 3-492-11923-9 .

- Ulrich Schneider : The Confessing Church between “joyful yes” and anti-fascist resistance. Brüder-Grimm-Verlag, Kassel 1986, ISBN 3-925010-00-9 .

- Martin Greschat (ed.): Between contradiction and resistance. Texts on the memorandum of the Confessing Church to Hitler (1936). Munich 1987.

- Bertold Klappert : Confessing Church in Ecumenical Responsibility. Christian Kaiser, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-459-01761-9 .

- Alfred Salomon : Let's face the facts. A contemporary witness of the church struggle reports. Calwer Pocket Library Vol. 22. Calwer, Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-7668-3111-9 .

- Kurt Meier: Cross and Swastika. The Protestant Church in the Third Reich. Munich 1992, ISBN 3-423-04590-6 .

- Georg Denzler, Volker Fabricius (ed.): Christians and National Socialists. Frankfurt am Main 1993, ISBN 3-596-11871-9 .

- Wolfgang Gerlach: When the witnesses were silent. Confessing Church and the Jews. Institute for Church and Judaism, 2nd edition. Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-923095-69-4 .

- Ernst Klee : The SA of Jesus Christ. The church under the spell of Hitler . Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1993, ISBN 978-3-596-24409-6 .

- Wolfgang Benz , Walter H. Pehle (ed.): Lexicon of the German resistance. Frankfurt am Main 1994, ISBN 3-596-15083-3 .

- Manfred Gailus : But it tore my heart - The silent resistance of Elisabeth Schmitz . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2010, ISBN 978-3-525-55008-3 (with the anonymous memorandum she wrote “On the situation of German non-Aryans” (1935/1936) ).

- Wilhelm Koch, Hildegard Koch: "... but the bees sting at the back!" Wilhelm Koch in Sulzbach, a pastor on the Confessional Front in Thuringia 1933–1945 (= wanted 8, Weimar-Apolda history workshop in the Prager-Haus Apolda eV). Apolda 2013, ISBN 3-935275-23-4 .

- Walter Schmidt : Johannes Halm (1893-1953). Resistance and persecution of the evangelical pastor from Auras / Oder in the period from 1933 to 1945. In: Specialized prose research - border crossing. Volume 8/9, 2012/2013 (2014), pp. 517-545.

- Hans-Rainer Sandvoss : "It is asked to monitor the church services ..." Religious communities in Berlin between adaptation, self-assertion and resistance from 1933 to 1945 . Lukas-Verlag, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-86732-184-6 .

- Karl Ludwig Kohlwage : The theological criticism of the Confessing Church of the German Christians and National Socialism and the importance of the Confessing Church for the reorientation after 1945. In: Karl Ludwig Kohlwage, Manfred Kamper, Jens-Hinrich Pörksen (ed.): “Was vor God is right ”. Church struggle and theological foundation for the new beginning of the church in Schleswig-Holstein after 1945. Documentation of a conference in Breklum 2015. Compiled and edited by Rudolf Hinz and Simeon Schildt in collaboration with Peter Godzik , Johannes Jürgensen and Kurt Triebel. Matthiesen Verlag, Husum 2015, ISBN 978-3-7868-5306-0 , pp. 15-36 ( online at geschichte-bk-sh.de ).

- Jürgen Sternsdorff: Gerrit Herlyn between the cross and the swastika. Loyalty to Adolf Hitler in the Confessing Church. According to unpublished sources. Vertaal & Verlaat publishing house, Marburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-86840-012-0 .

- Marie Begas: Diaries on the church struggle 1933–1938 (= publications of the Historical Commission for Thuringia, large series, volume 19). Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2016, ISBN 978-3-412-20661-1 .

- Karl-Heinz Fix, Carsten Nicolaisen, Ruth Papst: Handbook of the German Protestant Churches 1918 to 1949. Organs - offices - people. Volume 2: State and provincial churches (= work on contemporary church history, volume 20). 1st edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2017, ISBN 978-3-525-55794-5 .

Web links

- The Confessing Church. ( Memento from February 8, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) German Historical Museum

- The Barmen Theological Declaration . Full text on the website of the Evangelical Church in Germany

- On the way to the responsible community. Learning location Martin-Niemoeller-Haus, Berlin-Dahlem

- Karl Barth on the Confessing Church . From the documentary by Heinz Knorr YES and NO, Karl Barth in memory . Calwer Verlag, 1967. Excerpt from YouTube (2:00 minutes)

- German Historical Museum Foundation - The Confessing Church

- Evangelical Resistance: Brother Council of the Thuringian Confessing Church

- Evangelical Working Group for Contemporary Church History, Research Center Munich

- History workshop: The Confessing Church in Schleswig-Holstein and its impulses for the design of the church after 1945.

Individual evidence

- ↑ On the way to a responsible congregation: The Evangelical Church in National Socialism using the example of the Dahlem congregation (1982) - Church emergency law: Second Dahlem Confession Synod. Friedenszentrum Martin Niemöller Haus eV, October 30, 2010, accessed on August 29, 2018 .

- ↑ Walter Künneth: Answer to the Myth. The choice between the Norse myth and the biblical Christ . Wichern-Verlag, Berlin 1935.

- ↑ Rudolf Homann: The Myth and the Gospel. The Protestant Church in defense and attack against the "Myth of the 20th Century" by Alfred Rosenberg. Taking into account the recently published publication “To the dark men of our time” . West German Luther Verlag, Witten 1935.

- ↑ Harald Iber: Christian Faith or Racial Myth. The engagement of the Confessing Church with Alfred Rosenberg's "The Myth of the 20th Century" . P. Lang, Frankfurt 1987.

- ↑ Suggested by Paul Humburg , pastor in Barmen-Gemarke, who encountered the word on a tombstone in the Netherlands ( wuppertal-barmen.de ).

- ^ Kurt Dietrich Schmidt : Questions about the structure of the Confessing Church . First published in 1962. In: Manfred Jacobs (Hrsg.): Kurt Dietrich Schmidt: Collected essays . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1967, pp. 267-293.

- ↑ Exhibition “On the way to a responsible congregation - The Evangelical Church under National Socialism using the example of the Dahlem congregation”: Plate 14 - Illegality must be organized (catalog 17). In: niemoeller-haus-berlin.de. Archived from the original on January 23, 2012 ; accessed on May 4, 2020 .

- ↑ Martin Greschat (ed.): Between contradiction and resistance. Texts on the memorandum of the Confessing Church to Hitler (1936) . Munich 1987, p. 117.

- ↑ Jürgen Sternsdorff: Gerrit Herlyn between cross and swastika. Loyalty to Adolf Hitler in the Confessing Church. According to unpublished sources. Marburg 2015, pp. 100-103.

- ↑ As a result of his research on the Confessing Church in Berlin, the political scientist and historian Hans-Rainer Sandvoss stated: “The Confessing Church was not a resistance movement against National Socialism - that is, it was not 'anti-fascist' either - but a diverse internal church movement against 'Gleichschaltung' 'through the DC and state church policy. But in its struggle to defend itself against the internal church leader principle, against the marginalization of Christians of Jewish origin and by making public violent measures against evangelical lay people and pastors, it presented an incalculable and sometimes dangerous challenge for the NS power apparatus and its ideological guardians As early as the 1930s, National Socialism sought a totalitarian, violent, dynamic-aggressive national community for its long-term policy of conquest (which it achieved very successfully across all classes, especially within the younger generation) and in this way (itself) the Confessing Church disrupted the planned process of the Instrumentalization of fanatical masses. ”(In: “ It is asked to monitor the church services… ”. Religious communities in Berlin between adaptation, self-assertion and resistance from 1933 to 1945 , Lukas Verlag für Kunst- und Geistesgeschichte, Berlin 2014, P. 313.)

- ↑ a b Quoted from: Martin Stöhr: "... I was silent": On the question of anti-Semitism in Martin Niemöller. Martin Niemöller Foundation, January 9, 2007, archived from the original on January 21, 2007 ; accessed on May 4, 2020 .

-

↑ Pioneer of Christian-Jewish dialogue: Hermann Maas biography has now appeared in the book series of the city of Heidelberg. Website of the city of Heidelberg, accessed on January 1, 2020 . Markus Geiger: Hermann Maas - A love for Judaism, life and work of the Heidelberg pastor of the Holy Spirit and Baden prelate . In: Peter Blum on behalf of the city of Heidelberg (ed.): Book series of the city of Heidelberg . tape

XVII.4 . Regional culture publishing house, Ubstadt-Weiher 2016, ISBN 978-3-89735-927-7 . - ↑ Discussion in the BK about the Stuttgart confession of guilt: Exhibition “On the way to the responsible congregation - The Evangelical Church in National Socialism using the example of the Dahlem congregation”: Plate 36 - Reformation or Restoration? (Catalog 38). In: niemoeller-haus-berlin.de. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011 ; accessed on May 4, 2020 .

- ↑ Bernhard Heinrich Forck: And follow their faith - memorial book for the martyrs of the Confessing Church. On behalf of the Brother Council of the Evangelical Church in Germany. Evangelisches Verlags-Werk, Stuttgart 1949, DNB 451318099 .

- ↑ Jürgen Sternsdorff: Gerrit Herlyn between cross and swastika. Loyalty to Adolf Hitler in the Confessing Church. According to unpublished sources. Marburg 2015, pp. 101 f., 196; Pp. 69, 74-76, 118, 152-154, 195 f., 202-206.

- ↑ Hans Prolingheuer: Small political church history. Cologne 1984, pp. 98f., 190f.

- ↑ Hans Prolingheuer: Small political church history. Cologne 1984, p. 191.

- ↑ Tell me , Pastor, how did you get into the SS? Report by a pastor of the Confessing Church about his experiences in the church fight and as SS-Oberscharführer in the Hersbruck concentration camp. 2nd Edition. Brunnen-Verlag, Giessen 1983.