Bad Oeynhausen

| coat of arms | Germany map | |

|---|---|---|

|

Coordinates: 52 ° 12 ' N , 8 ° 48' E |

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | North Rhine-Westphalia | |

| Administrative region : | Detmold | |

| Circle : | Minden-Lübbecke | |

| Height : | 55 m above sea level NHN | |

| Area : | 64.83 km 2 | |

| Residents: | 48,604 (Dec. 31, 2019) | |

| Population density : | 750 inhabitants per km 2 | |

| Postcodes : | 32545, 32547, 32549 | |

| Primaries : | 05731, 05734 | |

| License plate : | MI | |

| Community key : | 05 7 70 004 | |

| LOCODE : | DE BOY | |

| City structure: | 8 districts | |

City administration address : |

Ostkorso 8 32545 Bad Oeynhausen |

|

| Website : | ||

| Mayor : | Achim Wilmsmeier ( SPD ) | |

| Location of the city of Bad Oeynhausen in the Minden-Lübbecke district | ||

Bad Oeynhausen [ baːtˈʔøːnhaʊzn ] is a town in the Minden-Lübbecke district in northeastern North Rhine-Westphalia . The city was founded as a spa in the 19th century after a thermal spring was drilled in its area . In the following years it developed into a spa resort of national importance with an originally by Peter Joseph Lenne garden architecturally framed spa . Today it is the location of numerous specialist clinics, in particular the Heart and Diabetes Center North Rhine-Westphalia . The Wittekindshof diaconal facility in the Volmerdingsen district emerged from the activities of the evangelical revival movement that was widespread in East Westphalia .

After the Second World War, the city briefly served as the seat of the British military government before it moved to Berlin after the Potsdam Conference . The headquarters of the British Army on the Rhine remained in Bad Oeynhausen until 1954.

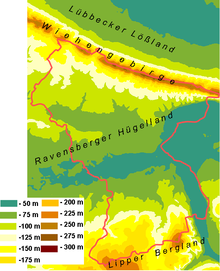

Bad Oeynhausen is the second largest city in the district with almost 50,000 inhabitants. It lies between the Wiehengebirge in the north and the Lipper Bergland in the south in the Werre valley , which flows into the Weser in the Rehme district . The city received its current expansion through the merger of the former city of Bad Oeynhausen with the surrounding communities of the former Rehme office through the Bielefeld law in 1973.

geography

Geographical location

Bad Oeynhausen is the southernmost municipality in the Minden-Lübbecke district on the south side of the Wiehen Mountains in the Ravensberg hill country . Only the district of Bergkirchen encroaches on the north side of the Wiehengebirge in the area of the pass road to Hille .

The course of the Werre , which crosses the city from west to east and flows into the Weser in the Rehme district, is characteristic of the city's location . The Weser forms the eastern city limits. The main traffic routes such as the Cologne-Mindener Railway and the Autobahn 30 , which run through the urban area along the river, run in the Werre Valley . The city center and the districts of Lohe, Oberbecksen and Rehme are located south of the Werre, the other districts to the north of it. On both sides of the river valley, the hill country gradually rises . In the north, the city extends to the ridge of the Wiehengebirge, which separates the city from the core area of the district. In the south, the city rises from the Werre lowlands into the Lipper Bergland .

The lowest point of the urban area is 45 m above sea level. NHN on the Weser, the highest at 269 m above sea level. NHN on the Wiehengebirgskamm. The area of the urban area is 64.83 km² with a largest extension of 12.5 km in north-south direction and 10.3 km in east-west direction.

Natural structure and nature protection

Bad Oeynhausen is located in the Lower Weser Uplands in the northwestern part of the Lower Saxony Uplands as part of the German low mountain range . In the system of natural spatial division of Germany , it largely belongs to the Ravensberger Hügelland (system code 531) and with a small part to the Eastern Wiehen Mountains (532); this part of the wooded ridge of the Jurassic Wiehengebirge is called "Bergkirchener Eggen" (532.3).

The south adjoining Ravensberger Hügelland consists of the northern Quernheimer Hügelland (531.01) and the Oeynhausener Hügelland (531.21) south of the Werre. Both are flat undulating hilly lands that are partly heavily cutted by brooks; Typical are the box valleys called Sieke . The largest part of the urban area is formed by rocks of the Lower Jura ( Lias ), which is partly covered by boulder clay and partly by loess; the southern part of the hill country lies on the rocks of the Upper Muschelkalk ( Keuper ).

The hill country is divided by the west-east running Werre lowland (531.11) with alluvial clay soils. The deepest strip , located directly on the lower Werre , is at risk of flooding and is partially surrounded by dikes . The dike is maintained by the Werre Water Association.

In the far east, the urban area on the western bank of the Weser has a share in the floodplain areas of the Rehmer valley widening (366.00).

During the Quaternary Ice Age, the surface shape was strongly influenced by glacial formation processes. During the Saale glaciation , the area was located in the area of the Nordic lowland glaciers , which came from Scandinavia ; numerous decorative erratic boulders in the urban area bear witness to this. In the periglacial climate of the Vistula glacial period , the relief was reshaped, the sieves were created, and a layer of loess of locally different thicknesses was blown. The Werre accumulated the lower terrace , consisting mainly of sand and gravel , into which it cut postglacial and, after being later filled with alluvial clay, formed a flood-prone flood plain .

In the urban area are six smaller protected areas , mainly along the Sieke, and the four protected landscapes Wiehengebirge and foothills, Wulferding Sener creek valley, Werre lowland and Oeynhausener hills. A landscape plan came into effect on December 29, 1995. Both the narrower spa area and a large part of the wider area of Bad Oeynhausen are designated as a thermal spring protection area.

In the urban area of Bad Oeynhausen there are around 30 natural monuments , from the Krausen beech in Eidinghausen to the hornbeam in the spa gardens of Bad Oeynhausen. There are also 10 protected landscape components , including stream valleys, groups of trees and a former quarry.

Use of natural resources

The healing springs are linked to the tectonic fault system of the Piesberg-Pyrmonter saddle. The boreholes reach close to the surface into the lower Jurassic, in deeper areas in the layers of the middle Keuper and the middle Muschelkalk and the deepest boreholes into the middle red sandstone . It is assumed that the water bodies are connected to the Zechstein below .

The planned mining of ice-age gravel deposits in the Weseraue in the Rehme district is controversial. The city of Bad Oeynhausen and some residents have filed a lawsuit against the dismantling permit; the nature conservation associations BUND and NABU expect an ecologically valuable meadow landscape to emerge after the economic use.

The suitability of the urban area for near-surface geothermal energy use is shown in the adjacent map. In Bad Oeynhausen there is potential for the efficient use of geothermal energy, but its use is limited by the fact that a large part of the urban area is designated as a water protection area.

The wind energy is only used in two 80 kW systems . Due to the high density of settlements, only a smaller wind priority area has been designated in the Wulferdingsen district, but this option has not yet been used.

Settlement area and central local hierarchy

Bad Oeynhausen is part of a densely populated area in the northern region of East Westphalia-Lippe , which extends as a band from Gütersloh via Bielefeld and Herford to Minden and is accessible via the Hamm – Minden railway line, federal highway 61 and motorways 2 and 30. The city center has grown together with the Gohfeld district of Löhn. The closest regional centers are Bielefeld, about 39 kilometers to the southwest, Osnabrück , about 50 kilometers to the west, and the state capital of Hanover, about 80 kilometers to the east .

The neighboring communities in the east are the town of Porta Westfalica , in the north with the border on the Wiehengebirgskamm the town of Minden and the community of Hille and in the northwest the community of Hüllhorst . The towns of Löhne and Vlotho of the Herford district adjoin to the west and south .

The state planning classifies Bad Oeynhausen like its four neighboring cities as middle centers ; only the municipalities of Hille and Hüllhorst are considered basic centers . Since these are functionally oriented more towards Minden or Lübbecke, the middle center Bad Oeynhausen lacks a clearly identifiable surrounding area .

City structure

According to its main statute, the city of Bad Oeynhausen consists of eight districts which, as formerly independent municipalities under Section 17 of the Bielefeld Act , were merged to form the new city of Bad Oeynhausen on January 1, 1973. According to Section 1 (2) of the main statute, the district that covers the area of the previous city of Bad Oeynhausen (until 1972) also bears the name "Bad Oeynhausen". The term “Bad Oeynhausen (old)” is also used for this district; in this article it is referred to as " Bad Oeynhausen (city center) ".

Parts of the former communities Rothenuffeln (4 ha) and Gohfeld (62 ha) were also added. The districts of Bad Oexen (Eidinghausen), Bergkirchen (Wulferdingsen) and Oberbecksen (Rehme) are among the districts mentioned.

| district | Residents |

|

|---|---|---|

| City center | 16,387 | |

| Stupid | 3,183 | |

| Eidinghausen | 7,816 | |

| Tan | 3,447 | |

| Rehme | 7,933 | |

| Volmerdingsen | 3,652 | |

| Werste | 6,759 | |

| Wulferdingsen | 3,319 |

Data collection by the city of Bad Oeynhausen, number of residents including secondary residences: as of December 31, 2018

Land use

As a potential natural vegetation that would be established without further human intervention in the landscape, was a species-poor mixed beech for the Ravensberger hills, the Wiehengebirge and the southern high-altitude areas of Oeynhausener hills a Luzulo-Buchwald determined. The natural vegetation has been greatly changed by the people who work and their cultural landscape, most of the forest areas have been removed.

The fertile soils are used intensively for agriculture, so that overall there is only a small forest area.

The administratively regulated land use is specified in a land use plan.

| Territorial unit | Settlement and traffic areas |

Agricultural area |

Forest area |

other open spaces |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| City of Bad Oeynhausen (2015) | 39.5% | 50.2% | 8.4% | 1.9% |

| District of Minden-Lübbecke (2015) | 20.0% | 64.0% | 11.9% | 4.1% |

| Detmold administrative district (2015) | 18.8% | 56.2% | 22.7% | 2.3% |

| State of North Rhine-Westphalia (2015) | 22.9% | 48.1% | 26.0% | 3.0% |

climate

Bad Oeynhausen, like all of East Westphalia-Lippe, is in the "zone of warm-temperate rainy climates" (climate type Cfb) according to the Köppen / Geiger climate classification, with year-round precipitation and a monthly average temperature of over -3 ° C in the coldest month. The monthly average temperatures are consistently below 22 ° C, whereby 10 ° C must be exceeded in at least 4 months.

According to the Troll / Paffen classification, the climate (climate type III, 3) is called the “sub-oceanic climate of the cool temperate zone”; A typical criterion for this is an annual fluctuation in the monthly average temperatures of at least 16 ° to a maximum of 25 °. In terms of the spa climate, it is also referred to as a “mildly stimulating healing climate”.

history

Until the city was founded

A megalithic stone chamber grave in Werste is the oldest evidence of human settlement in today's urban area. The oldest mention of a current part of the village is evidence of the place “Rehme” (“Rimie”) for the years 753 and 785 in the Frankish imperial annals , when the Frankish kings Pippin the Younger and his successor Charlemagne went there on campaigns. Medieval settlement centers also contain the districts of Werste, Eidinghausen, Volmerdingsen and Wulferdingsen.

In Bergkirchen at the transition over the Wiehengebirge a mountain spring shrine in pre-Christian Saxon times is assumed, in the place of which a church was built in the 9th century, a predecessor of today's church.

The territorial allocation of today's urban area, the southern part of which belonged to the County of Ravensberg and the northern part to the Minden monastery, was important for the development of the settlement . Both were in insignificant peripheral locations, so that the settlement cores did not develop into central locations without a location advantage and because of the lack of sovereign support. The districts located on it could not derive any economic advantage from the Weser either, as there was no port.

It was not until 1719 that the county of Ravensberg, which had been in Brandenburg since 1614, was jointly administered with the principality of Minden, which had also been in Brandenburg since 1648, as the administrative unit of Minden-Ravensberg .

At the time of the Napoleonic Wars, the area from 1807 initially belonged to the Weser department of the Kingdom of Westphalia , namely the area north of the Werre to the canton of Haddenhausen in the Minden district and the area south of it to the canton of Vlotho in the Bielefeld district . This border function of the Werre increased from 1810 to the state border, after part of the Kingdom of Westphalia had been incorporated into the French Empire . The area north of the Werre now belonged to the canton Mennighüffen of the French district of Minden in the department of the Upper Ems , while the southern part in the Kingdom of Westphalia was assigned to the canton of Vlotho in the Bielefeld district of the department of Fulda .

After Napoleon's defeat at the Battle of Leipzig the area in 1813 came into the Prussian General between the Weser and the Rhine and was after the Congress of Vienna fully re the 1815 Prussia incorporated. In the reorganized Prussian state, all of East Westphalia belonged to the administrative district of Minden within the province of Westphalia . The places Wulferdingsen, Volmerdingsen and Werste were assigned to the Minden district . The places Rehme, Niederbecksen and Dehme, which formed the parish of Rehme, remained in the Herford district and only became part of the Minden district in 1832.

After the discovery of a salt spring in the Sältewiesen of the Werreniederung (located roughly in today's area of Mindener Strasse, Heinrichstrasse and Königstrasse), King Friedrich II ordered the construction of a salt works , which was named "Königliche Saline Neusalzwerk" and in 1753 produced evaporated salt for the first time. By 1760 two graduation towers and in 1768 a two-story " graduation house " were built. The salt was sold in the region, but also sold as far as Cologne. A chemical factory was built next to the salt works, which processed residues of the crude salt into products such as soda , chlorinated lime and Epsom salt . The coal required for production came from the Bölhorst hard coal mine near Minden, 90% of which was sold to Rehme-Neusalzwerk in the 18th century.

The Chaussee von Minden, today's Mindener Strasse, which led to the saltworks around 1800 , was led further west from 1801–1803 and is now called Herford Strasse . Later it formed the northern border of the narrower spa area.

In 1752 the government issued a “New Salt Regulations for the Minden, Ravensberg, Lingen and Tecklenburg Provinces” which, among other things, regulated the prohibition of salt imports from abroad and the compulsory purchase of salt for private individuals (“conscriptions”). The state salt monopoly existed until 1867. The Rehmer saltworks produced until 1928.

After various other boreholes for the development of salt deposits, which should make the Prussian state independent of salt imports, the mining captain Karl von Oeynhausen unexpectedly came across a thermal brine spring in 1839 . During the development of the spring between 1839 and 1845, several private baths operated by local farmers used the healing water. After the completion of the drilling, the private pools were nationalized and officially licensed on June 30, 1845. King Friedrich Wilhelm IV was personally committed to the emerging health resort; between 1817 and 1857 he visited the place at least seven times. It is assumed that the architecture-loving monarch was also involved in the planning of the first bathhouse is likely, but has not been clearly proven.

The spa as a city

The health resort was initially referred to as “Brine bath near Neusalzwerk”, “Brine bath near Rehme” and “Bad Rehme”; In 1848 Friedrich Wilhelm IV gave it the name "Royal Bad Oeynhausen". In addition, the names "Rehme (Bad Oeynhausen)", "Bad Oeynhausen bei Rehme" and "Bad Oeynhausen (Rehme)" were still in use for a while.

Prince Regent Wilhelm ordered the establishment of the spa as a city on January 1, 1860. The 266.6 hectare urban area with 1273 inhabitants was formed from parts of the municipalities of Rehme , Werste and Gohfeld-Melbergen. Bad Oeynhausen was named after the discoverer of the thermal brine spring and is one of the few German cities whose name refers to a person who was not a sovereign sovereign.

The young town was initially administered according to the Prussian rural community code and only received full town charter in 1885 , at the same time it left the office of Rehme. The fact that the western part of the spa district was located in the area of the Gohfeld municipality in the Herford district , which was perceived as unfavorable , was corrected by the government during the development of the town by expanding the area in favor of Bad Oeynhausen, which also moved the border between the Minden and Herford districts to the west has been.

| year | Spa guests |

|---|---|

| 1846 | 777 |

| 1849 | 1,781 |

| 1860 | 1,797 |

| 1870 | 2,389 |

| 1880 | 3,557 |

| 1908 | 15,369 |

| 1913 | 18,145 |

| 1919 | 26,131 |

| 1922 | 19,949 |

| 1923 | 14,036 |

| 1937 | 16,280 |

| 1940 | > 20,000 |

The connection to the railway network with two stations by the Cöln-Mindener Railway in 1847 and the Weserbahn in 1875, which directly affect the spa gardens, contributed significantly to the upswing of the spa town.

South of the Cöln-Mindener Railway, near the train station, the spa gardens were created according to plans by the garden architect Peter Joseph Lenné . The new place developed around the spa gardens; up to the First World War, houses for the upper middle class and numerous pensions were built. Larger representative buildings in the city center were the spa and bathing hotels Hohenzollernhof (1900) and Königshof (1914/1917).

Bad Oeynhausen was in competition with other seaside resorts that had been founded earlier and had further developed the spa infrastructure; The Prussian sovereigns after Friedrich Wilhelm IV preferred other health resorts. Bad Oeynhausen became a bath for the bourgeois middle class and the lower nobility. Already in the first decades of the spa business, opinions in Bad Oeynhausen differed greatly as to whether one should develop into a sophisticated luxury bathroom or whether one should meet the needs of less income-generating, but “really sick” guests. From the end of the 19th century, more and more people with social insurance came to Bad Oeynhausen. The Johanniter Order Houses were founded in Bad Oeynhausen in 1878 as "Asylum for needy bathers".

The number of spa guests increased sharply up to the First World War, declined after the start of the war, but was more than compensated for by the stay of soldiers in need of recovery in the following period. A similar course was also evident during the Second World War . After the First World War, the total number of spa guests fell below the pre-war level; the number of foreign spa guests (mainly from the Netherlands and Northern Europe, before the First World War also from Russia) could never again reach the pre-war level. The importance of social security cures continued to grow; In 1925 the State Insurance Institution (LVA) opened its first sanatorium in Bad Oeynhausen. Between 1924 and 1929 Bad Oeynhausen was the only German spa with an airfield with flight operations.

At that time, the reasons for the decline in spa guests were the development towards luxury baths, the neglect of spa guests with social insurance and the competition from nearby Bad Salzuflen in Lippe , which had found a new mineral spring and was doing a lot of advertising. While Bad Oeynhausen had about 15,000 spa guests in 1938 as in 1907, the number of spa guests in Bad Salzuflen rose sharply from 7,000 to 30,000 during this period. The accessibility of the spa facilities played a major role in the state bath for the numerous wheelchair users. In 1925, the slogan “City without steps” was coined for Bad Oeynhausen; In connection with this, Bad Oeynhausen became more and more a place for the treatment of the seriously ill, while Bad Salzuflen concentrated on those in need of relaxation. In 1932 a balneological institute was founded in Bad Oeynhausen under the direction of Klotilde Gollwitzer-Meier , which was connected to the University of Hamburg .

The health resort and the state saltworks were incorporated in 1924 under the name "Bad und Salzamt Bad Oeynhausen" into the "Preussische Bergwerks- und Hütten-Aktiengesellschaft" ( Preussag ), since 1930 as "Bad Oeynhausen GmbH". Salt production was stopped in 1928 due to inefficiency and the two graduation towers were demolished by 1940.

| Parties | 1919 | 1932 |

|---|---|---|

| DVP | 30.1% | 6.3% |

| DDP | 24.1% | 0.8% |

| DNVP | 21.5% | 24.9% |

| SPD | 18.3% | 17.5% |

| center | 6.0% | 4.6% |

| NSDAP | - - | 38.2% |

After the November Revolution of 1918, the introduction of universal suffrage , women's suffrage and the reform of the party structure in the German Reich, the political orientation of the Bad Oeynhausen population also became clear. In the election to the German National Assembly in Weimar on January 19, 1919, the parties that supported the democratic system received great support: the two liberal parties DVP and DDP as well as the SPD and the Catholic Center ; the right DNVP was rejected. In the last Reichstag election on November 6, 1932, before the so-called seizure of power , the overwhelming majority voted for the right-wing parties NSDAP and DNVP, while the SPD and the center narrowly maintained their positions and the liberal parties DVP and DDP became meaningless.

Based on the sources, it is unclear whether a woman was elected as a council member for the first time in 1929; The appointment of Hildegard Neuhäusser, widow of the former mayor Fritz Neuhäusser , as the next female member is certain for 1945 .

National Socialism and World War II

In February 1936, the fourth Reich Synod of the Confessing Church took place in Bad Oeynhausen under difficult conditions under the leadership of President Karl Koch , who was active as a pastor in Bad Oeynhausen at the time.

The bath anti-Semitism typical of many health resorts was also evident in Bad Oeynhausen during the Nazi era , although consideration had to be given to foreign health resort guests who complained about political demonstrations. The local NSDAP local group leader organized a public rally in August 1935 with Ludwig Münchmeyer , a " Reich speaker " of the NSDAP , against the mayor, because he wanted to prevent the installation of an advertising box for the anti-Semitic combat paper Der Stürmer at the town hall. During the Third Reich, eleven streets or squares in what was then Bad Oeynhausen were renamed for political reasons, in Rehme there were twelve.

The number of Jews living in Bad Oeynhausen changed little for decades and was 81 in 1933. These included the variety artists Walther and Hedwig Flechtheim , who performed in Bad Oeynhausen between 1920 and 1932 (duo "Monroe & Molly") . The religiously bound Jews belonged to the Jewish community of Vlotho, where a synagogue was located. In Bad Oeynhausen there was a prayer house that was also used by Jewish spa guests. As far as is known, 21 people emigrated during the Nazi era; the rest were mostly victims of deportations, which began in spring 1942, and extermination campaigns. In the urban area, a number of stumbling blocks and a memorial in Volmerdingsen remind of the former Jewish residents. A memorial fountain for the Jewish victims was built at the Protestant Church of the Resurrection.

→ List of stumbling blocks in Bad Oeynhausen

In September 1939 Bad Oeynhausen was connected to the Reichsautobahn (now: A 2 ) in what is now the Rehme district .

During the Second World War , 20 hospitals for the wounded were set up in Bad Oeynhausen, while the spa operations were increasingly restricted; in January 1945 there were only around 1,000 civilian spa guests. Bombing raids in June and November 1944 and shortly before the end of the fighting in March 1945 did not target the inner city and the spa area, which remained undamaged, but rather the Weser bridges and the Weserhütte armaments factory . The Weserhütte part in World War II to the German armaments industry and guns produced as tanks and anti-aircraft guns , armored cars and armored personnel carriers . Part of the production came with the so-called U-relocation to the nearby Wiehengebirge.

In April 1945 Bad Oeynhausen belonged to the so-called Weser Line , a line of defense. The Weser bridges were prepared for demolition by April 2nd and secured with all ferry points and crossings. When the American 47th Panzer Grenadier Battalion wanted to take the still intact motorway bridge over the Weser, it was blown up by German forces. The war ended in Bad Oeynhausen on April 3, 1945 with the surrender of the city and the military hospitals to the 5th Panzer Division of the US Army without a fight , which was confirmed in writing at 2 p.m. As early as April 11, the British military administration appointed Carl Jäcker as Mayor of the Rehme Office, and on April 13, Walter Kronheim as Mayor of Bad Oeynhausen.

After the Second World War

The British occupation

After the Second World War, the Allied military used the infrastructural possibilities of the mostly undamaged health resorts to accommodate administrations: the Americans in Wiesbaden , the French in Baden-Baden and the British in Bad Oeynhausen. Like the other two allies, the British army also decentralized its administration, for which purpose it confiscated the health resorts of Bad Oeynhausen, Bad Salzuflen , Bad Lippspringe , Bad Driburg , Bad Hermannsborn , Bad Eilsen , Bad Nenndorf and Bad Rehburg . The high command of the British military government was established in Bad Oeynhausen.

On May 3, 1945, the British Military Administration ordered the evacuation of a large part of the city center and the confiscation of 959 houses with 1807 apartments. By May 12, 1945, around 9,000 people had to leave the area. This meant a loss of 55% of the housing stock for 70% of the population. The expellees were mostly housed in the surrounding villages, where there were already many refugees from the eastern regions and evacuees from the Ruhr area. Up to 6,000 British people lived in the restricted area, which was fenced off by barbed wire. The patients of the city hospital were relocated to the Wittekindshof, shops were forcibly relocated and a temporary business center was built north of the northern railway.

The headquarters of the command staff of the British Rhine Army was housed in the Hotel Königshof, which had been used as a hospital until the end of the war . The Kurhaus served as a team fair for up to 3000 members of the army, Bathhouse III as a cleaning bath, Bathhouse IV as an administration building and Bathhouses I and II as a furniture and clothing store. In the foyer were NAAFI -Shops operated and precipitated in the severely damaged by tanks rides spa due to lack of fuel trees. The commander received an official residence unofficially known as the "White House" in 1950 on the Schützenstraße in place of a burnt in June 1945 Villa. By 1954 there had been 32 small and medium-sized fires, four major fires and three total fires, in which several buildings that were important for the spa town were destroyed: including the Church of the Resurrection at the spa park (1947), the music pavilion at the spa house (1951) and the former bath house II 1952), which is now replaced by the Gollwitzer-Meier Clinic. The background to these fires could never be clarified.

For logistics, the British set up the Porta Westfalica airfield in nearby Vennebeck , had the barriers lifted in several phases from January 1948 and the Weserhütte was confiscated in the same year in order to set up the main workshop for the repair of army vehicles. The “Notgemeinschaft Bad Oeynhausen e. V. “as a representation of the interests of Bad Oeynhausen citizens towards the British.

The post-war construction

| year | Spa guests |

|---|---|

| 1955 | 14,325 |

| 1960 | 42,131 |

| 1965 | 50.185 |

| 1972 | 64,460 |

After the complete clearance of the inner city by the British in 1954, the repair of the damage - supported by generous compensation payments - tackled, with the aim not only of restoring what had been destroyed, but also of extensive redesign. When designing the new buildings, they were committed to modernity , and they were looking for an "uncompromisingly different architectural language". Bath houses II, III (1955) and V (1958) were demolished, bath house IV (today II) was renovated and rebuilt from 1956. The side wings of the Kurhaus were demolished, a modern porch was built and a concert space was created at the Kurhaus. Between 1960 and 1965 the spa park was completely redesigned according to plans by the garden architect Hermann Mattern .

After bathing began again, the number of spa guests was initially at the pre-war level and then rose sharply. Since the 1950s, the spa system has been characterized by drastic qualitative and quantitative changes. The increasing “clinification” of the cure with medical and therapeutic care for patients under one roof with a simultaneous sharp decline in traditional, privately financed spa cures also led to the construction of numerous spa clinics in Bad Oeynhausen, especially in the western spa area; the accommodation of guests in small pensions became less important. The result was a strong growth of the health clinics from 14,200 guests in 1973 to 48,422 in 1991. Another consequence was the conversion of pensions that are no longer needed to old people's homes, condominiums, shops, practices, etc. a.

In the 1960s, the secondary schools were combined in two school centers: the North School Center in Eidinghausen on the Werste border and the South School Center in the east of the city center near the Rehme border. In the latter, the formerly independent high schools for boys (Immanuel-Kant-Gymnasium) and for girls (Luisenschule) were combined into one school in 1969, which was also named Immanuel-Kant-Gymnasium.

Expansion of the urban area by merging municipalities

Part of the Niederbecksen community was incorporated into the city as early as 1926. Shortly after the end of the war, Mayor Kronheim submitted an application on May 22, 1945 for a reorganized town with the current districts and Gohfeld, which met with fierce resistance from the surrounding communities and was unable to assert himself with the British military authorities.

At the beginning of 1973, the state of North Rhine-Westphalia dissolved the previous office of Rehme with a regional reform and united its communities with the previous city of Bad Oeynhausen. The new town thus formed was also given the name "Bad Oeynhausen". Its population was more than double and its area more than eight times that of the former town of Bad Oeynhausen.

Since then, the urban area has expanded considerably to the north as far as the Wiehengebirgskamm, to the east to the Weser and also to the south. The demarcation of the border in the west was very controversial: the old town of Bad Oeynhausen wanted to draw a border further west on the Mittelbach , so that a significant, densely populated part of the former Gohfeld community would have come to the new town of Bad Oeynhausen. This was justified with the population oriented towards Bad Oeynhausen in terms of infrastructure and shopping behavior. The city was not listened to with this argument, probably also because of the recent municipal reorganization of the city of Löhne and the Herford district , the results of which should no longer be touched. The council representatives of the Rehme Office, which was to be fully integrated into the new town of Bad Oeynhausen, also spoke out in favor of the current solution with a border on the Osterbach . As a result, part of the spa area has been on the territory of Löhne since then and is referred to as the “Löhne spa area in the Oeynhausen state spa”.

The development of the new town of Bad Oeynhausen

The health reforms of the 1990s in Bad Oeynhausen - as in many other health resorts - led to a sharp decline in the number of spa guests. The spa facilities of the Staatsbad , until then owned by the State of North Rhine-Westphalia, have been operated by the Staatsbad Bad Oeynhausen GmbH since the municipalization in 2004; however, the designation Staatsbad may continue to be used.

Due to the expandable commercial areas of the incorporated districts, Bad Oeynhausen received a second economic pillar as a commercial and industrial location in addition to the health sector.

The British armed forces were finally withdrawn from the city of Bad Oeynhausen in 2014 . The former residential building of the commanding officer of the Herford garrison, known in Bad Oeynhausen as the “White House”, was then auctioned. The buildings of a terraced housing estate on Porta- and Gneisenaustrasse, built for British soldiers' families between 1955 and 1957, have meanwhile been partially used to accommodate refugees and then transferred to the normal housing market.

In 1964, the redesign of the inner city of Bad Oeynhausen into a pedestrian zone began, whereby the continuous connection of the B 61 with Herford and Mindener Strasse was interrupted for individual traffic . The new A 30 coming from the west was brought up to the city limits in 1969, and the Bad Oeynhausen motorway junction was built near the Weser in the Rehme district to connect the A 30 to the A 2 (approval 1979); In order to cope with the traffic flows from the A 30 to the A 2, the west-east street of Kanalstrasse / Mindener Strasse was expanded to four lanes and became part of the B 61. The motorway gap, the course of which was highly controversial in the city, was made by the so-called northern bypass after eleven years of construction in December 2018. There is a long-term artistic observation of this building, the documentary film Autobahn , which premiered at the documentary film festival DOK Leipzig 2019.

In 2013 the city bought the historic reception building of the Bad Oeynhausen Nord train station and from 2018 carried out a public participation process for further use. A renovation is planned from 2019; after completion, the city's own Staatsbad GmbH will move in there.

Population development

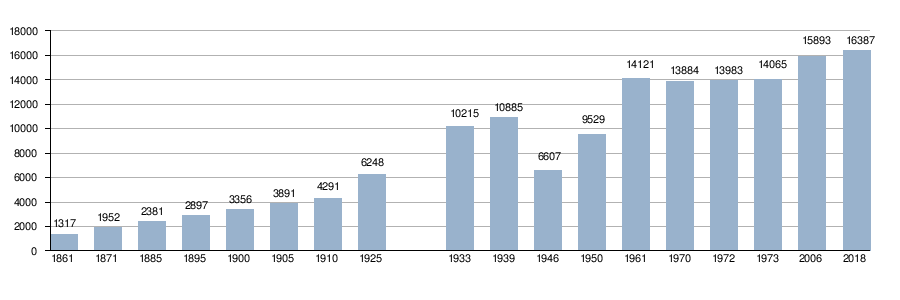

Old town of Bad Oeynhausen until 1972 and the “city center” district since 1973

The table and the diagram show the population of the city of Bad Oeynhausen up to 1972 and of the same area of Bad Oeynhausen (city center) from 1973 according to the respective territorial status. A relevant change in the territorial status resulted from the incorporation of part of the community Lohe on April 1, 1926 (1925: 2942 inhabitants).

The numbers are census results up to 1970. The data relate since 1871 and for 1946 to the local population and Present 1925-1970 to the resident population . Before 1871, the number of inhabitants was determined according to inconsistent survey procedures.

|

|

|

|

1926 incorporation of the Lohe district; from 1973 data collection by the city of Bad Oeynhausen, number of residents including secondary residences

City of Bad Oeynhausen since the territorial reform in 1973

The population of the newly formed town of Bad Oeynhausen, which was created in 1973 through the unification of eight towns under the Bielefeld Act , has increased slightly since it was founded. According to the municipal reference of the Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning , Bad Oeynhausen is classified as a " small medium-sized town ".

| year | Residents |

|---|---|

| 1973 (January 1) | 44,983 |

| 1975 (December 31) | 44,730 |

| 1980 (December 31) | 44,336 |

| 1985 (December 31) | 43,215 |

| 1987 (May 25) ¹ | 44,036 |

| 1990 (December 31) | 46,475 |

| year | Residents |

|---|---|

| 1995 (December 31) | 49.014 |

| 2000 (December 31) | 50.007 |

| 2005 (December 31) | 49,221 |

| 2010 (December 31) | 48,300 |

| 2015 (December 31) | 48,990 |

| 2017 (December 31) | 48,747 |

¹ census result ;

Data from the State Office for Information and Technology in North Rhine-Westphalia (IT.NRW).

Typical of Bad Oeynhausen is the slightly higher proportion of the older age groups in the resident population. This can be explained by the fact that numerous retirees, pensioners and other elderly people have chosen Bad Oeynhausen as their retirement home because of the diverse medical care, but also because of the state spa facilities.

| Territorial unit | up to 17 years | 18-64 years | 65 years and more |

|---|---|---|---|

| City of Bad Oeynhausen (2016) | 16.8% | 60.7% | 22.6% |

| District of Minden-Lübbecke (2016) | 17.6% | 60.8% | 21.6% |

| Detmold administrative district (2016) | 17.6% | 62.0% | 20.4% |

| State of North Rhine-Westphalia (2016) | 16.6% | 62.6% | 20.7% |

Religions

Due to its location in the former Principality of Minden , where the Reformation took hold in the 16th century, the city is predominantly evangelical. In 1992 there were 36277 Protestants compared to only 5340 Catholics. In all districts there are parishes of the Evangelical Church of Westphalia , of which the parish Bergkirchen belongs to the parish of Minden , the rest belong to the parish of Vlotho . The Christ Church in the city center is the church of the Evangelical Free Church Community.

The immigration of Catholics began with industrialization and the construction of railways, they came mainly from Westphalia, the Rhineland and Saxony; Workers from Silesia and Italy were also employed in the construction of the Southern Railway. The establishment of the spa led to the formation of a Catholic parish in 1861; The first church was built for these and the Catholic spa guests in 1871. The current Catholic parishes of St. Peter and Paul and St. Johannes Evangelist belong to the pastoral area WerreWeser in the deanery of Herford-Minden of the Archdiocese of Paderborn .

The Bad Oeynhausen congregation of the New Apostolic Church comprises the area of Löhne and Bad Oeynhausen and has its church in the city center .

Other religious communities are the Adventist Church, the Good News Congregation, the Baptist Brethren Congregation, and the Jehovah's Witnesses.

The nearest mosques of Muslim communities are in Wages, and in the neighboring cities of Vlotho and Minden.

politics

City administration

In 1930 the city bought what was then the vacant hotel "Vier Jahreszeiten" in order to use it as the town hall. After the end of the British occupation, it turned out to be in dire need of renovation and unsuitable for administration, which is why it was demolished. At the same place, a typical authority building was built according to the plan of the architect Hanns Dustmann , which has been the city administration's headquarters since 1957 as town hall I. The building has been a listed building since 2010 and was renovated in 2011.

The administration building of the former Rehme district in the Werste district is used as Town Hall II, with mainly technical areas. There are also four other branch offices of the city administration; earlier plans to concentrate administration in a new building are no longer being pursued.

Bad Oeynhausen City Council

The Bad Oeynhausen City Council has 44 seats. In addition, the mayor is the council chairman. The members of the council are elected for a term of five years. The City Council holds its meetings in City Hall I.

| year | CDU | SPD | Green | BBO 1 | FDP | UW 2 | LEFT | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 16 | 14th | 5 | 4th | 1 | 2 | 2 | 44 |

| 2009 | 15th | 14th | 4th | 4th | 3 | 2 | 2 | 44 |

| 2004 | 18th | 16 | 7th | - | 3 | - | - | 44 |

| 1999 | 22nd | 16 | 4th | - | 2 | - | - | 44 |

1 "Citizens for Bad Oeynhausen" 2 "Independent voters Bad Oeynhausen"

The City Council of Bad Oeynhausen has not yet made use of its right under Section 39 of the municipal code for the state of North Rhine-Westphalia to divide the urban area into districts (localities) and to form district committees there or to appoint local councilors.

mayor

→ List of mayors of Bad Oeynhausen

According to the municipal code for the state of North Rhine-Westphalia , the mayor, directly elected by the population, is the head of the city; he presides over the city council and heads the city administration.

The current mayor, Achim Wilmsmeier (SPD), as a joint candidate from the SPD, the Greens, UW, BBO and the Left, won the mayoral election on September 13, 2015 against Kurt Nagel (CDU) as the runner-up in the first ballot with a relative majority of votes. Other candidates were the mayor Klaus Mueller-Zahlmann (SPD), who had been in office since 2004 and who ran as an individual applicant, and another individual applicant. In the required runoff election on September 27, 2015, Achim Wilmsmeier defeated Kurt Nagel with 53.85% of the vote, who received 46.15%, and took over the office on October 21, 2015.

Coat of arms, flag, banner and seal

The city of Bad Oeynhausen was granted the right to use a coat of arms , a flag and a banner by the district president in Detmold on December 13, 1973 .

| Banner, coat of arms and flag | |

|

|

|

|

- Coat of arms:

| Blazon : “In blue , a silver ( white ) four-rung ladder . Above that, separated by a silver (white) wavy bar , in a red shield head three silver (white) merlettes . " | |

| Reasons for the coat of arms: The coat of arms, which has existed since 1863, quotes the family coat of arms of the von Oeynhausen family with the head . Karl von Oeynhausen made a name for himself by drilling the first brine spring for the city. The Merletten in the Schildhaupt come from the coat of arms of the former Rehme Office , the area of which forms a large part of the area of today's city. |

- Flag:

- The flag, which the city of Bad Oeynhausen is allowed to fly, is in the city colors blue-white-blue in a ratio of 1: 3: 1 with the city's coat of arms shifted from the center to the pole.

- Banner:

- The official banner of the city is in the colors "From blue-white-blue in a ratio of 1: 3: 1 striped lengthways with the city's coat of arms in the upper half."

- Official seal:

- Bad Oeynhausen has an official seal that shows the city's coat of arms. After a decree of the North Rhine-Westphalian Minister of the Interior of March 1, 1973, all old coats of arms and seals of the united communities including the old town of Bad Oeynhausen were suspended.

Town twinning

Bad Oeynhausen maintains partnerships with the following European municipalities, after which streets or squares in Bad Oeynhausen are named. The partnerships are maintained by the partnership ring of the city of Bad Oeynhausen e. V.

The partnership that the municipality of Eidinghausen concluded with the French city of Fismes in Champagne in 1968 was transferred to the city of Bad Oeynhausen as part of the municipal reorganization.

In 1977 Bad Oeynhausen entered into a connection with the English District Wear Valley in County Durham . This no longer exists as an official partnership since 2014 after the partnership association in Wear Valley dissolved.

The most recent town twinning has existed since 1989 with the Polish town of Inowrocław in the Kujawy-Pomeranian Voivodeship , which is based on a shared past of salt production and brine baths, both towns owe to the drilling of Baron von Oeynhausen.

Spa facilities

The mineral springs

Since the middle of the 18th century, numerous springs for salt and thermal brine extraction have been drilled. The oldest still existing spring is the Bülow-Brunnen (1806) in the Sielpark, whose brine was used for the salt production for the salt works. A thermal brine appeared for the first time in 1839 with the Oeynhausen spring; When it was completed in 1845, the world's largest drilled depth of 696.4 m was reached. The characteristics of the source were described by Alexander von Humboldt while the drilling was still in progress .

Changes in the spring discharge and the brine properties made further drilling necessary over the course of time, of which the following are still available: the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Sprudel (1898), the Morsbach-Sprudel (1906), the Jordan-Sprudel (1926), the the largest carbonated thermal brine spring in the world is the Kurdirektor-Dr.-Schmid-Quelle (1966, the most mineral-rich spring with 86 g / L), the Alexander-von-Humboldt-Sprudel (1973, deepest spring with 1034 m) and the Gert -Michel-Sprudel (1995). In contrast to these deep boreholes, a near-surface brine was extracted from Wittekind Well I (1876), which was once the world's most important calcium chloride source; meanwhile it has been shut down and replaced by the Wittekind fountain II. Most of the healing springs produce iron and carbonated thermal brine, while the Alexander von Humboldt hot spring produces iron sulphate brine.

The importance of the springs for the spa business has decreased significantly in the last few decades. Sole is still used from the Kurdirektor-Dr.-Schmid-Quelle, the Oeynhausen-Sprudel in Badehaus II and the Alexander-von-Humboldt-Sprudel in the Porta Westfalica Clinic. The Bali-Therme wellness bath in the spa park is partially supplied with brine from the Gert-Michel-Sprudel and the Jordan-Sprudel.

Spa area and park

For the needs of the health resort, the health resort area Staatsbad Oeynhausen was designated, which in the city center connects directly to the west of the inner city business center and in the west extends beyond the city limits to the area of Löhne-Gohfeld. There are significant road traffic restrictions in the spa area.

The heart of Bad Oeynhausen is the approx. 26 hectare Bad Oeynhausen spa park , which was created between 1851 and 1853 according to plans by Peter Joseph Lenné . The basic structure of the original complex with the Korso-Ring is still reflected in the street scene. The park has been adapted to the changing design goals over time and is part of the European Garden Heritage Network . The spa park has been open to the general public all year round for several years; an earlier fence was removed. The fountain of the Jordansprudels , named after the spa and salt works director Albert Jordan (1865–1934), is the symbol of the city of Bad Oeynhausen. In the summer season, it jumps for five minutes every full hour between 9 a.m. and 8 p.m.

In order to function as a state spa, numerous spa buildings were built in the spa park with an architecture in the style of classicism , neo-baroque and neo-renaissance , which testify to a glamorous and sophisticated spa and spa world at the beginning of the 20th century and which were comparable to those of other well-known spa towns. The neo-baroque Kurhaus (plans by Hinckeldeyn and Delius ) was built between 1905 and 1908 and also housed a casino from 1980 to 2002 ; Today there is a GOP variety theater , a restaurant and a discotheque in the current Kaiserpalais . The late Classicist bath house I was built in 1852–1857 (according to plans by Robert Ferdinand Cremer and Carl Ferdinand Busse ), today's bath house II (formerly bath house IV) was built in 1885 in the style of a Renaissance palace and the house of the guest in 1903, in which the tourist is located -Information is located. The neo-baroque theater dates from 1915, and the neoclassical foyer from 1926 (interior painting by Gustav Halmhuber ) replaced a drinking pavilion from 1858.

In 1960, a bathhouse built in modern style was opened between the spa gardens and Oeynhauser Switzerland , which was named Badehaus II because the earlier, wooden bathhouse II burned down in 1952. The spa administration later found its home in this new building. After a fire in 2002, the ruins were finally removed in 2015. Since then, the former bath house IV has been called bath house II.

A stylistic contrast is the Ronald McDonald house of the architect Frank O. Gehry . The roof, shaped like a snail shell, screwed up twelve meters. The house with 12 apartments should be a temporary home for parents or other relatives of children with heart disease, as long as the little patients are treated in the Heart and Diabetes Center North Rhine-Westphalia in Bad Oeynhausen.

According to the original plan, the Protestant Church of the Resurrection stands on the eastern edge of the spa park , a three-aisled hall building by the architect Diez Brandi from 1956 to replace the first building that burned down in 1947, and on the western edge the Catholic parish church of St. Peter and Paul after a previous building from 1871.

In a south-westerly direction, the spa park is extended by the extensive grounds of the Siekertal landscape park with a large population of trees, in which the local history museum is located. The Oeynhauser Schweiz lies - separated by buildings - east of the spa gardens. It is a landscape park and urban forest with a fallow deer enclosure .

The Sielpark is a large landscaped park north of the spa park between the northern railway line and the Werre. Inside is the fountain house with the Bülow fountain. The fountain feeds the graduation tower built in the Sielpark in the 1990s , a replica of a predecessor at the former Neusalzwerk saltworks.

Spa and health care facilities

Bad Oeynhausen has numerous clinics of local, regional and national importance. In line with the long-term changes in the management of the spas, a number of specialized spa and rehabilitation clinics were created. The Gollwitzer-Meier-Klinik and the Klinik am Rosengarten are located on the Kurpark area. The Klinik am Korso is the only German clinic that specializes exclusively in the treatment of eating disorders .

The Diabetes Clinic Bad Oeynhausen , which has been located on Wielandstrasse since 1965, was one of the two germ cells of the Heart and Diabetes Center (HDZ), which is attached to the University Hospital of the Ruhr University Bochum and also works with Bielefeld University . The other nucleus was the Gollwitzer-Meier Clinic, which was to be expanded to include a surgical department. In 1980, the city of Bad Oeynhausen and the state of North Rhine-Westphalia founded a hospital operating company in equal parts and decided on a spacious new building, which was built on a site on Georgstraße near the diabetes clinic and the city hospital and put into operation in 1985. The HDZ is by far the largest heart transplant center in Europe.

The Bad Oeynhausen Municipal Hospital, which was previously located on Weserstraße, was evacuated to Wittekindshof after the war and, from 1950 to 1953, was given a new building outside the restricted military area on Wielandstraße, provides standard medical care for the population.

The Auguste Viktoria Clinic was founded in 1913 at Sielpark as a children's hospital, has been a specialist orthopedic hospital since 1964 and, like the Bad Oeynhausen Hospital, belongs to the group of Mühlenkreiskliniken .

The Bad Oexen Clinic is the only clinic outside the spa area in the half of the city north of the Werre. It is located in the Eidinghausen district in the middle of an extensive spa park and has specialized in oncology aftercare.

Culture and sights

Theaters and museums

Guest performances by foreign theaters and concerts by the Bielefelder Philharmoniker and the Northwest German Philharmonic take place in the Theater im Park . The GOP Varieté in the Kaiserpalais is also located in the Kurpark.

The German Fairy Tale and Weser Legends Museum is a collection of fairy tales from the Weser Uplands region, based primarily on the work of the Brothers Grimm . The private collection of folklorist and writer Karl Paetow , who died in 1992, formed the basis of the museum, which was opened in 1973 in the rooms of the Paul Baehr Villa, a splendid villa in the style of historicism on the Kurpark. Bad Oeynhausen is part of the German Fairy Tale Route .

The rural building and cultural history of the Minden-Ravensberg area is presented in the Bad Oeynhausen museum courtyard in the Siekertal landscape park. It is an open-air museum with relocated buildings (main house from 1739, Heuerlingshaus from 1654, Spieker , barn, bakery , court water mill from 1772) and a cottage garden.

Buildings outside the spa area

The development of the health resort, which began slowly from the middle of the 19th century and was particularly intensified from around 1880, offered the image of “Wilhelminian uniformity” with many buildings, mostly in individual locations, in a style typical of the time. Although there was no war-related destruction, urban renewal measures from the 1950s onwards changed this picture considerably through demolition and facade design. The removal of a building in which the city had allocated ghetto-like living space to Jewish citizens who had to leave their homes under the regulations at the time, met with public criticism.

The evangelical church Bergkirchen in a scenic location on the pass of the Wiehengebirge , the Laurentiuskirche in Rehme and the tower of the evangelical church Volmerdingsen are the only medieval church buildings in the city area.

The Schoenen mill in the Bergkirchen district is still in its original location as a water mill . Like the water mill in the Bad Oeynhausen museum courtyard, it is part of the Westphalian Mühlenstraße . A number of preserved and restored bakeries, mainly in the northern parts of the city, bear witness to the earlier rural everyday culture.

The moated castle Ovelgönne from the 18th century is located in the Eidinghausen district .

Immediately to the west of the spa park, a residential area based on the garden city concept was built in the 1920s , today's Hindenburgstrasse monument area.

The energy forum innovation by architect Frank O. Gehry on the B 61 is a sign of new industrial architecture .

Monuments

The Flößer monument (1992) at the confluence of the Werre into the Weser points to the earlier importance of the Weser as a supra-regional waterway. The founding myth of salt discovery by pigs engages pigs Fountain (1981) to thematically. The Hygieia sculpture and the Najade fountain in the pedestrian zone in the city center refer to Bad Oeynhausen's spa function. The Oeynhausen bust (1895) in front of bath house I and a stele in the spa gardens (1887) commemorate the technical founder of the bath. A replica of a Lenné bust (1847) by Christian Daniel Rauch , reminiscent of the garden architect, has stood in the extreme northeast corner of the spa park on Herford Street since 1982 .

Green spaces and recreation

In the summer months, a tourist train called "Emil - der Wolkenschieber" (Emil: electric mobility) runs through the spa area and the parks and regularly serves various routes. A second vehicle was named "Minna" because of its conventional drive.

In the so-called flood basin, the flood area of the Werre north of the Sielpark, a show jumping competition has been set up.

The Aqua Magica is a 20 hectare landscape park in Bad Oeynhausen and Löhne , known as the "Park of Magical Waters" , designed by the French landscape architects Henri Bava and Olivier Philippe for the Bad Oeynhausen / Löhne 2000 horticultural show. The most impressive work of Aqua Magica is the "water crater", an accessible, underground fountain sculpture. There has been a high ropes course on the site since 2009 , which is open on weekends and during school holidays.

The ten cemeteries in the city area are in all parts of the city except the city center . The old town community established its cemetery, today the largest in Bad Oeynhausen, from 1910 in the area of the Werste district; from 1935 a second large cemetery was built on Mooskamp in the Rehme district near the motorway. All cemeteries are administered by the Bad Oeynhausen cemetery association.

Sports

The sport is organized in over forty clubs and a city sports association. In regional games above the district class in men's soccer, SV Eidinghausen-Werste and FC Bad Oeynhausen play, in men's and women's handball the HCE Bad Oeynhausen, in table tennis the TTU Bad Oeynhausen.

Every spring, the German Show Jumping Championship takes place on the Flutmulde tournament site.

Regular events

The city festival "Innenstadtfete" always takes place on the last weekend before the start of the summer holidays. The “Festival by Citizens for Citizens” has regularly attracted around 50,000 visitors from the city and the surrounding area for over 40 years.

The "park lights" take place every year at the beginning of August in the spa gardens. The event has its origins as a celebration of the opening of the spa gardens by the British occupying forces in 1956. It has changed over time and now lasts three days with offers for all age groups. For some years now, well-known musicians have also been hired to perform. The highlight of the event is traditionally a fireworks display on Saturday evening.

Every year in summer, the “Poetic Sources” literature festival, which lasts several days, takes place on the Aqua Magica site.

Others

A cultural meeting point is the printing shop meeting center in the city center, where the Bad Oeynhausen adult education center is also based.

In the forum of the Heart and Diabetes Center, art is shown in changing exhibitions.

Economy and Infrastructure

economy

Based on its function as a health resort, Bad Oeynhausen developed a cluster profile as a health location. Due to the dominant health sector, the spa town has a comparatively high proportion of employees in the service sector.

The research facility Heart and Diabetes Center North Rhine-Westphalia , which was founded in 1980 and has been part of the University Clinic of the Ruhr University Bochum since 1989 , has more than 2,000 employees. The nearby municipal hospital has 550 employees. For this purpose, a spatial merger with the Auguste-Viktoria-Klinik is sought, both of which belong to the group of Mühlenkreiskliniken .

Clinic operations and tourism are very important to Bad Oeynhausen. In 2018, with 121,597 guest arrivals, the highest number since 1973, the beginning of statistical recording, was reached. The number of overnight stays peaked at 980,474 in 2014 and was 926,409 in 2018.

In addition to the clinics and spa facilities, there are also numerous old people's and nursing homes in the urban area. The largest employer in Bad Oeynhausen is the Wittekindshof diaconal foundation with its business headquarters in the Volmerdingsen district. The Wittekindshof offers around 3,300 jobs.

The manufacturing industry consists mainly of medium-sized companies without individual companies dominating the city's economy. The nine designated industrial areas are located in all parts of the city except Volmerdingsen, with the core city being largely kept free of manufacturing as a health resort. Important branches are wood and plastic processing and mechanical engineering.

The Stadtsparkasse , founded in 1862, merged in 2018 with the neighboring town of Porta Westfalica to form Sparkasse Bad Oeynhausen-Porta Westfalica , based in Bad Oeynhausen. The cooperative organized Volksbank Bad Oeynhausen-Herford based in Herford has emerged from a series of mergers.

Employees subject to social security contributions

| Territorial unit | Agriculture and Forestry | Manufacturing | Commerce, transport and hospitality | other services |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| City of Bad Oeynhausen | 0.2% | 22.4% | 16.6% | 60.8% |

| Minden-Lübbecke district | 0.5% | 33.8% | 19.8% | 46.0% |

| Detmold administrative district | 0.6% | 34.8% | 21.2% | 43.4% |

| State of North Rhine-Westphalia | 0.5% | 26.9% | 22.4% | 50.2% |

Data as of June 30, 2017

The disposable income of 25,004 euros per inhabitant in 2017 was above the district average of 23,427 euros and above the national average of 22,263 euros; This puts Bad Oeynhausen in 77th place of all 396 communities in North Rhine-Westphalia. The purchasing power of the Bad Oeynhausen population is close to the national average and clearly exceeds the Minden-Lübbecke district ( GfK purchasing power index (Bad Oeynhausen): 99.5, national average: 100, Minden-Lübbecke district: 95.7; data as of 2015).

Established businesses

The Denios AG in Dehme is a leading company with products and services for the environmental protection and safety in the workplace. Balda Medical, which belongs to the Stevanato Group and manufactures medical technology products in Wulferdingsen, continues the name of the former Balda AG, a manufacturer of plastic components for medical devices and electronic products. The Buschjost company, founded in Bad Oeynhausen, is part of the international IMI group of companies and produces valve technology products at its location in the Lohe district . Bad Oeynhausen is also the location of Battenfeld-Cincinnati with products for plastics processing ( extrusion technology ).

trade

The retail trade is concentrated in the city center south of the Nordbahnhof and east of the spa gardens. A quarter of all retail businesses in the city are located there in predominantly small, mostly owner-managed business units; Branches of large retail chains are hardly represented. With the City Center from the 1970s located directly at the Nordbahnhof and the Lenné-Karree opposite, which opened in 1999, there are two small inner-city business centers, but there are no large providers with a magnet function in this area. The shops mainly cover the medium-term demand, the basic suppliers such. B. Supermarkets are mainly located in the sub-centers of the city districts.

In order to protect inner-city trade, the council rejected the settlement of large-scale retail establishments in 1979, but later approved the construction of the Werre Park in view of the development of shopping centers in the neighboring cities , which has been offering ample parking space on the site of the former Weser hut on the B 61 since 1998 lies. The choice of location corresponded to the general tendency of the late 1990s to locate shopping centers in or near the city center. At a distance of only 1.5 km, there was a strong competitive situation with the city center, whose competitive weakness, which is expressed in under-use and vacancies, existed in the 1990s before the Werrepark opened.

The Bad Oeynhausen casino has been located next to the Werre Park since 1999 , and the city has a share in the revenue from the casino tax, and a cinema complex .

Further retail sub-centers are located in the area of the city center known as "Südstadt" on Detmolder Strasse and Weserstrasse as well as in the Werste, Eidinghausen and Rehme districts. Local suppliers are represented in all other districts .

media

The daily newspapers Neue Westfälische and Westfalen-Blatt , based in Bielefeld, produce local editions for Bad Oeynhausen. The local radio is the Minden-based Radio Westfalica . Bad Oeynhausen is in the catchment area of the public West German Broadcasting Corporation (WDR), which maintains a regional studio in nearby Bielefeld and produces regional radio and television programs from here.

Public facilities

The district court of Bad Oeynhausen has been located on Herford Street since 1879 and has been housed in a representative building complex on Bismarck Street since 1911. It is responsible for the jurisprudence in the cities of Bad Oeynhausen, Löhne and Vlotho and, as the central register court, manages the trade , cooperative and association registers of the Herford and Minden-Lübbecke districts.

Stadtwerke Bad Oeynhausen (AöR), a subsidiary of the city, has been responsible for supply and disposal since 2007 . The area of responsibility includes street and green space maintenance, street cleaning, parking lot management and sewage and waste disposal, with individual tasks being transferred to private companies. The municipal utilities operate the natural gas supply together with Gelsenwasser Energienetze GmbH . The power grid in the city belongs to WestfalenWeser Netz GmbH , in which Stadtwerke is a shareholder.

The Bad Oeynhausen fire brigade is made up of full-time and voluntary workers; the main station is located on Königstrasse in the city center. There are fire fighting groups of the volunteer fire brigade in all parts of the city.

education

The city of Bad Oeynhausen has six primary schools at a total of nine locations in each district. The Immanuel-Kant-Gymnasium and the Realschule Süd are located in the south school center, in the east of the city center ; in the north school center in the Eidinghausen district, the Realschule Nord, the comprehensive school and the Bernart School, a special needs school. The city has an adult education center and a music school in the city center .

Bad Oeynhausen is part of the Freiherr-vom-Stein-Berufskolleg (school center south) in the sponsorship of the district and location of the school at Weserbogen - West school for the physically handicapped of the regional association Westphalia-Lippe (school center north). Other schools are the education center of the Federal Office for Family and Civil Society Tasks Bad Oeynhausen of the Federal Voluntary Service in Rehme, the Evangelical Vocational College and the Vocational Training Center of the Wittekindshof in Volmerdingsen.

The Bad Oeynhausen public library is located in the Lenné-Karree commercial and office complex in the city center.

traffic

Rail transport

Bad Oeynhausen is located on two railway lines and is the only town in the Minden-Lübbecke district with two passenger stations.

The Bad Oeynhausen station ( "North Station") stands since 1847 at the Hamm-Minden railway (Northern Railway), the former Cologne-Minden railway . There are IC connections to Berlin, the Rhine-Ruhr area and Amsterdam. Regional Express trains run every hour to Hanover - Braunschweig and Düsseldorf ( Westfalen Express ) , every two hours to Osnabrück - Rheine and Minden - Nienburg .

The Bad Oeynhausen Süd train station ("Südbahnhof") has been served by the Weserbahn (Südbahn) since 1875 . The platform is accessible for disabled people without steps.

The city belongs to the Westfalentarif tariff association . On the regional trains, the Lower Saxony tariff and the Lower Saxony ticket also apply on some lines (the tariff limit in the direction of North Rhine-Westphalia is Herford).

Public bus transport

The urban area is served by city and regional buses . In some cases, minibuses are used on call lines (“Taxibuses”). The brand name for the city bus network has been Der Oeynhauser since August 2019 . The regional buses run u. a. to Löhne, Minden, Hüllhorst and Hille.

Road traffic

Besides Porta Westfalica, Bad Oeynhausen is the only town in the Minden-Lübbecke district with a motorway connection ( A 2 and A 30 ); in addition, the federal highways B 61 and B 514 run through the city.

Between 1969 and 2018, the traffic flows between the two autobahns were 6.7 km in length through the urban area - sometimes in close proximity to the spa area. To close the gap, the so-called north bypass was built in an eleven-year construction period from 2007 and released on December 9, 2018 in the direction of Osnabrück. Since August 2, 2019, the other direction of travel has also been unrestricted.

Individual traffic in the city center is influenced by the two railway lines, the Werre, the inner-city pedestrian zone and the traffic-calmed spa area. The northern parts of the city are connected to the southern parts by just two Werre bridges. The Südbahn crosses the heavily frequented Detmolder Strasse between the Südbahnhof and the Kurpark with a barred level crossing. The Herford Street, which used to function as the main road (B 61), is part of the pedestrian zone between the city center and the north train station and north of the spa park and is completely closed to private traffic, resulting in large detours for traffic from the residential areas west of the spa park to the east and south.

The opening of the Heart and Diabetes Center (HDZ) in 1985 brought with it a further "urban development and traffic problem", which was planned in close proximity to the municipal hospital in the residential area of the so-called "poet's quarter" without affecting the limited capacity of those there Take residential streets for delivery, business and visitor traffic and the lack of parking facilities into consideration, as the city car parks are too far away. After the city's plan to allow the HDZ to build a parking lot on a nearby site in a purely residential area failed in 2018 before the Higher Administrative Court of Münster, the city withdrew from the procurement of parking spaces and passed the responsibility for the solution to the HDZ .

From Bad Oeynhausen to the north, the Wiehengebirge can only be crossed via three pass roads (one state and two district roads ). Apart from the A 2, only the B 61 on the southern edge of the Wiehengebirge leads eastwards from the city. The next road bridges over the Weser are in the neighboring towns of Porta Westfalica-Hausberge and Vlotho. Bad Oeynhausen can be reached from the south and west via numerous roads in all hierarchical levels.

Bicycle traffic

Several long-distance cycle paths and local cycle paths cross Bad Oeynhausen: Mühlenroute , Weserradweg , Wellness-Radroute , Else-Werre-Radweg , Soleweg and others. The Weser can be crossed on the cycle path of the motorway bridge (A 2). The planned high- speed cycle route RS3 OWL should also lead through Bad Oeynhausen.

There is a bicycle station at the Nordbahnhof . Bicycle traffic is severely restricted in the city center (pedestrian zone).

Weser ferry

The Amanda ferry connects Bad Oeynhausen- Rehme with the leisure and local recreation area Großer Weserbogen in the Costedt district of the city of Porta Westfalica . It brings pedestrians and cyclists across the Weser from March to October. Traditionally, the ferry season is opened on Good Friday by the district administrator of the Minden-Lübbecke district and the mayors of Bad Oeynhausen and Porta Westfalica.

Air traffic

The nearest international airports are in Hanover-Langenhagen , Paderborn / Lippstadt and Münster / Osnabrück . The Porta Westfalica airfield in the Vennebeck district east of the Weser is of regional importance ; the city of Bad Oeynhausen holds a stake in the Flugplatzbetriebsgesellschaft mbH Porta Westfalica . It is primarily used for aviation, but is also of regional economic importance.

Others

As in many other places, the discovery of the first salty spring is entwined with an anecdote in which animals play an active role. After the pigs a colon Sültemeyer had wallowed in the mud in 1745, said to have been discovered on the skin a salt crust on them after drying out. Although this incident has not been proven in any written source, it has become a founding myth for Bad Oeynhausen. A source creation myth also plays a role in the Wittekindsquelle in the Bergkirchen district.

The sometimes misleading names of some important streets in Bad Oeynhausen are a curiosity. The Kaiserstraße , which leads south from the underpass under the northern railway, bears the name of a former resident. Gustav King , a former head of the volunteer fire department is, with the tapering to the central bus station Königstraße honored today is where the main fire station, but there is no road for the badgründenden King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. While reminding the north of the spa park located Wilhelmstrasse, the Augusta place and the Wilhelmsplatz to the successor King William I , his wife Queen Augusta and King (or Emperor) Wilhelm II. , however, with the nearby Elizabeth street Frederick William same wife, Queen not Elisabeth , but the hotel owner Elisabeth Vogeler honored which headed the local Red Cross , like several other streets, bear the first names of former residents (Heinrich-, Hermann-, Luisen- and Marienstraße as well as the Charlottenplatz).

In the main business zone, Klosterstrasse is reminiscent of the spa doctor Wilhelm Klostermeyer .

Personalities

Honorary citizen

- 1912 Paul Baehr (* 1855 in Thorn; † 1929 in Bad Oeynhausen), second mayor of the city, head of the city council, author of local literature about Bad Oeynhausen

- 2008 Reiner Körfer (born January 18, 1942 in Kleve), cardiac surgeon and medical director of the Heart and Diabetes Center NRW in Bad Oeynhausen

On April 5, 1933, the NSDAP Group proposed in the city council, which held 11 of 24 seats, the awarding of honorary citizenship to Adolf Hitler , Franz Seldte and Paul von Hindenburg . After the three SPD city councilors left the meeting, the meeting unanimously approved the motion. On May 7, 2014, these honorary citizenships were unanimously declared null and void by the city council , with three council members also not taking part in the vote.

Other personalities

In addition to the two honorary citizens, the theologians Karl Koch and Hans Thimme , both presides of the Evangelical Church of Westphalia , who did part of their theological work in Bad Oeynhausen, the folklorist and museum director Karl Paetow , the writer Johannes are among the important personalities of the city of Bad Oeynhausen Baptist Waas , the non-fiction author Rudolf Pörtner and the balneologist Klotilde Gollwitzer-Meier, who works in the spa town .

See also

- List of the municipalities of Westphalia A – E

- List of salt pans in Germany

- List of health resorts in Germany

- List of places with the suffix "Bad"

- List of closed British military bases in Germany

Movie

- Autobahn (film) , documentary film about the traffic situation in Bad Oeynhausen and the construction of the northern bypass, 2019, 85 min., Written and directed: Daniel Abma , premiere: DOK Leipzig 2019 ( autobahn-film.de ).

literature

City Chronicles

- Paul Baehr: Chronicle of Bad Oeynhausen (= history in the lower Werretal . Volume 4 ). Bielefeld 1909 (reprint 2009).

- Gerhard Lietz: Chronicle of the city of Bad Oeynhausen 1910–1972 . Bad Oeynhausen 1979.

- Werner Meyer zu Selhausen: Chronicle of the city of Bad Oeynhausen 1973–1992 . Bad Oeynhausen 1993.

Others

- The Alexander von Humboldt spring in Bad Oeynhausen. Geological State Office of North Rhine-Westphalia, Krefeld 1977, ISBN 3-86029-826-7 .

- Baldur Köster: Bad Oeynhausen. A 19th century architecture museum. Hirmer, Munich 1985, ISBN 3-7774-3930-4 .

- Baldur Köster: The restoration of bathhouse I in Bad Oeynhausen. In the years 1989–1992. Rasch, Bramsche 1992, ISBN 3-922469-74-4 .

- Johannes Henke: Bad Oeynhausen. The historic city with a future. Interesting facts from the history of the city in words and pictures. Geiger-Verlag, Horb am Neckar 1996, ISBN 3-89570-252-8 .

- Johannes Henke (Ed.): 150 Years of the Oeynhausen Spa. Horb am Neckar 1998, ISBN 3-89570-387-7

- Hans-Dieter Lehmann: Bad Oeynhausen. Old villas - seen in a new way. 2nd Edition. Publishing house for regional history, Bielefeld 2016, ISBN 978-3-7395-1037-8

- Gerhard Lietz, Hilda Lietz: Bad Oeynhausen in old views II. European Library, Zaltbommel 1999, ISBN 90-288-5377-4 .

- Manfred Ragati and others: Frank O. Gehry: The Energy Forum - Innovation in Bad Oeynhausen. Kerber Christof Verlag, Bielefeld 2000, ISBN 3-924639-64-7 .

- Rico Quaschny (ed.): Bad Oeynhausen between war and peace. The end of the war and the occupation in contemporary testimonies and memories (= history in the lower Werre Valley . Volume 1 ). Publishing house for regional history, Bielefeld 2005, ISBN 3-89534-621-7 .

- Rico Quaschny: City Guide Bad Oeynhausen (= history in the lower Werre Valley . Volume 2 ). Publishing house for regional history, Gütersloh 2007, ISBN 978-3-89534-652-1 .

- Rico Quaschny: The Luis School . On the history of higher education for girls in Bad Oeynhausen (= history in the lower Werretal . Volume 3 ). Publishing house for regional history, Gütersloh 2008, ISBN 978-3-89534-753-5 .

- Rico Quaschny: Friedrich Wilhelm IV. And Bad Oeynhausen (= history in the lower Werre Valley . Volume 6 ). Publishing house for regional history, Bielefeld 2011, ISBN 978-3-89534-896-9 .

- Friedhelm Pelzer: City of Bad Oeynhausen (= Carola Bischoff et al. [Hrsg.]: Cities and municipalities in Westphalia . Volume 13 ). Aschendorff Verlag, Münster 2013, p. 68-114 .

Web links

- Website of the city of Bad Oeynhausen

- Bad Oeynhausen State Bath

- Bad Oeynhausen in the Westphalia Culture Atlas

- Werre water association

Individual evidence

- ↑ Population of the municipalities of North Rhine-Westphalia on December 31, 2019 - update of the population based on the census of May 9, 2011. State Office for Information and Technology North Rhine-Westphalia (IT.NRW), accessed on June 17, 2020 . ( Help on this )