Elisabeth Schmitz

Elisabeth Schmitz (born August 23, 1893 in Hanau , † September 10, 1977 in Offenbach am Main ) was a resistance fighter against National Socialism from the ranks of the Confessing Church . She stood out above all with the memorandum on the situation of German non-Aryans , in which she predicted quite accurately as early as 1935 what would happen to the Jews in Germany with National Socialism . Your attempt to rouse the Evangelical Church and especially the Confessing Church to resist the persecution of the Jews was ineffective.

Life

origin

Schmitz was the youngest of three daughters of high school professor August Schmitz (* 1849 in Mönchengladbach , † 1943 in Hanau), who taught at the High State School in Hanau, and of Clara Marie, née Bach (* 1854 in Hanau; † 1929 ibid). She attended the Schillerschule (Realgymnasium) in Frankfurt am Main . In 1914 she passed the Abitur and then studied history , German and theology at the University of Bonn and from 1915 at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Berlin . Her most important academic teachers were the liberal church historian Adolf von Harnack and the historian Friedrich Meinecke . In 1920 she did her doctorate with Meinecke with a dissertation on Edwin von Manteuffel and graduated in 1921 with the first state examination in Berlin . During the school preparatory service that followed, Schmitz completed a supplementary course at the theological faculty, but she saw herself as a historian, not a theologian, throughout her life.

Elisabeth Schmitz belonged to the first generation of women in Germany who were able to study and to whom - albeit initially within narrow limits - an independent professional activity with an academic degree was open to them. According to the downsizing ordinance of October 27, 1923 , a woman in the public service had to remain unmarried and could not start her own family.

School service

After the second state examination in 1923, Schmitz was initially able to teach at various higher girls' schools in Berlin for six years only with temporary contracts. Until 1 April 1929, she was on Luisengymnasium (then Oberlyzeum , a girls' high school) in Berlin-Moabit as a secondary school teacher employed on permanent contracts. From 1933 she saw how Jewish or politically unpopular teachers were removed from schools. This also included her social democratic director at the Luisenschule. Elisabeth Schmitz soon ran into difficulties with the new director because of her rejection of National Socialism and in 1935 she was transferred to the school named after Auguste Sprengel (now Beethoven High School ) in Berlin-Lankwitz . This fate also met her colleague Elisabeth Abegg . In Lankwitz Dietgard Meyer became her student, to whom she later remained connected in decades of personal friendship and whom she referred to as a "daughter".

New curricula in 1938 had the primary objective of “ shaping the National Socialist people ” on a racist, militaristic and totalitarian basis. Elisabeth Schmitz could not and did not want to comply with this. The November pogroms in 1938 then prompted the then 45-year-old to seek retirement on December 31, 1938. Their reasoning was as courageous as it was life-threatening: "I have increasingly doubted whether I can teach my purely ideological subjects - religion, history, German - as the National Socialist state expects and demands of me." Contrary to expectations, the request was granted and she was even awarded a small pension.

Engagement in the Confessing Church

Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church and Dahlem

From around 1928 Elisabeth Schmitz was a member of the German Association for International Friendship Work of Churches . Since 1933 she was a member of the parish council of the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church and was in close contact with the parish priest Gerhard Jacobi . In 1934 Elisabeth Schmitz became a member of the Confessing Church . From 1936/37 she joined the confessional community in Dahlem with the local pastors Franz Hildebrandt and Martin Niemöller , whose unofficial successor was Helmut Gollwitzer from 1938 . She belonged to his "Dogmatic Working Group", in which, among other things, Karl Barth's Church Dogmatics was discussed. She also belonged to the Wednesday group of Anna von Gierke , social worker and Reichstag member of the DNVP . In 1933 she was dismissed as head of the youth home association training center because she was “ half-Jewish ” . Her like-minded colleagues also included the botany professor Elisabeth Schiemann from the Dahlem community and her former colleague Elisabeth Abegg. All three women were on friendly terms with women of Jewish origin.

Letters and memoranda against the persecution of the Jews

Schmitz turned to the theologian Karl Barth in April 1933, when the Jews' boycott of April 1, 1933 had started the exclusion of Jews. Her correspondence dates mainly from 1933 to 1936. She raised serious allegations of allegiance from the Protestant churches to Adolf Hitler , called for the Christian churches to contact representatives of Judaism and for active pastoral care for those persecuted in the concentration camps . She tried to get Barth to take a public position on the "Jewish question". In addition to the correspondence, several visits to Barth in his Swiss exile are documented. For Barth, however, the “Jewish question” was only one part of his discussion of the Nazi state . He declined to make a public statement.

At the same time, Schmitz began to work on a memorandum on the situation of the Jews under the National Socialists. This work, which she completed in September 1935, she gave the title On the Situation of German Non-Aryans . Here she brought together numerous examples of the plight of the Jews and the involvement of authorities, neighbors, colleagues, business partners and teachers in the everyday persecution . In this report, she combined the sober presentation of everyday discrimination with an urgent appeal to the responsible men of the church, including and especially the Confessing Church, to live up to their responsibility towards the people and the state. She produced around 200 copies of the font and sent or handed it over to members of the Confessing Church such as Karl Barth, Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Helmut Gollwitzer. To reduce the risk of her own persecution, she wrote the memorandum anonymously.

In contrast to Marga Meusel in her memorandum on the tasks of the Confessing Church to Protestant non-Aryans , Schmitz referred not only to baptized “non-Aryans”, but also called for the church to show solidarity with all those persecuted. While Meusel warned against resistance against the state, Schmitz called for resistance against the state persecution of Jews. With her emphasis on the Jewish roots of Christianity, she went far beyond the theological ideas then prevalent.

Schmitz tried to submit her memorandum to the Third Confessional Synod of the EKapU , which met in Berlin-Steglitz from September 23 to 26, 1935 , shortly after the Nuremberg Laws were passed . She wanted to induce the Confessing Church to publicly protest against the persecution of the Jews. However, the memorandum was not discussed at the synod and was hardly received within the church.

After the Nuremberg Laws came into force in September 1935, Elisabeth Schmitz wrote an "addendum" to her memorandum, which she completed on May 8, 1936. She pointed out the devastating consequences of these laws for those affected. With that, too, it had no effect.

After the November pogroms in 1938, Schmitz wrote two letters to Helmut Gollwitzer, in which she also demanded financial support for the beleaguered Jewish communities and providing them with churches for Jewish worship.

“When we were silent on April 1st, 1933, when we were silent about the striker boxes , about the satanic agitation in the press, about the poisoning of the souls of the people and the youth, about the destruction of livelihoods and marriages by so-called 'laws', about the Buchenwald's methods - there and a thousand times else we were guilty on November 10, 1938. "

Help for persecuted Jews

Since the transfer of power to the NSDAP , Elisabeth Schmitz has been helping her Jewish friends. She took in Martha Kassel, a Protestant baptized doctor of Jewish origin, who had lost her practice and thus her existence in 1933, for four years until shortly before she emigrated in December 1938. Because of this shared apartment with a Jewish woman, Elisabeth Schmitz was denounced and questioned by a block attendant in autumn 1937 . The district administration demanded that the school authorities dismiss them immediately. However, this put the case down. Her friend Elisabeth Schiemann also got involved in this way.

After leaving school, Schmitz volunteered with Bible studies and visiting services in the Friedenau confessional community around Pastor Wilhelm Jannasch , who also offered a contact point for persecuted Jews in Berlin. She gave baptism classes to Jews who wanted to be admitted to the church and had to go to the houses of the Jews, which were marked as "Jewish apartments".

In her apartment or in her weekend house "Pusto" in Wandlitz , which she had acquired at the end of 1938, Elisabeth Schmitz accommodated persecuted Jews, including Liselotte Pereles, Margarete Koch-Levy and the young Charles C. Milford (formerly Mühlfelder), whose father was picked up and had been taken to the notorious Rosenstrasse and whose mother had joined the protests there. It was probably many more Jews whom Elisabeth Schmitz helped with accommodation, money and ration cards in order to save them from the threatened deportation .

post war period

In 1943, Elisabeth Schmitz's Berlin apartment was destroyed by fire bombs and she lost almost everything. Therefore, she returned to her native Hanau in 1943. Elisabeth Schmitz lived in her parents' house in Hanau, which belonged to the parish of the Johanneskirche , even after the end of the war. In 1946 she was able to resume her school work and taught at the Karl Rehbein School in Hanau. She closely followed current developments in theology and the Church and the post-war debates in society. She retired in 1958. She was active in the Hanau History Association, in which she also promoted research on Jewish life in Hanau. Elisabeth Schmitz died on September 10, 1977 at the age of 84. The funeral took place in silence.

Appreciation

From the beginning, Elisabeth Schmitz recognized the unjust character of the Nazi state and consistently stood up for those who were racially persecuted. She tried again and again to mobilize the Evangelical Church against injustice. It clearly stood out from the vast majority of German Protestants . In her correspondence with prominent theologians and leading representatives of the Confessing Church, she advocated an unequivocal statement by the Evangelical Church on the “Jewish question”. These efforts culminated in her memorandum of 1935/1936, in which she described in detail the internal and external plight of the persecuted Jews and led a sharp accusation against the silence of the Church, especially the Confessing Church. “The Church makes it bitterly difficult to defend it”. They are characterized by their realistic assessment of the Nazi state, their extraordinary courage to express them publicly, and their exemplary, consistent personal attitude.

The importance of Elisabeth Schmitz has long been misunderstood. One reason for this was that the head of the Protestant District Welfare Office in Berlin-Zehlendorf , Marga Meusel , was the author of the memorandum for decades , an attribution that probably goes back to Wilhelm Niemöller . It was not until 1999 that Dietgard Meyer, now a retired pastor, published the memorandum under the correct author's name in an annotated edition with a biographical sketch.

In 2004 a bag with her legacy, consisting of seven files, was found in a cellar of the Johanneskirchen parish, the parish to which Elisabeth Schmitz belonged in Hanau. In addition to personal documents (certificates, transcripts, correspondence), the files also contained booklets with handwritten draft texts for the memorandum on the situation of German non-Aryans . How and when the bag got to where it was found and who left it there could no longer be determined. The documents are now in private hands and are to be handed over to the Berlin State Library in the future .

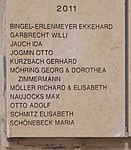

That her commitment remained largely unknown is also shown by the fact that she was only recognized as Righteous Among the Nations by the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial in 2011 .

Honors

- The Evangelical Church of Kurhessen-Waldeck and the city of Hanau honored Elisabeth Schmitz in 2005 with a memorial stone on the Hanau cemetery.

- On November 11, 2011, Elisabeth Schmitz was posthumously awarded the honorary title “Righteous Among the Nations” by the Israeli Holocaust Memorial Center Yad Vashem. Yad Vashem paid tribute to the help she provided to persecuted Jews in Berlin. The certificate from Yad Vashem and her briefcase are on display in the Karl Rehbein School in Hanau.

- In 2013, the city of Hanau honored Elisabeth Schmitz with a plaque on her home and birthplace on Corniceliusstrasse in Hanau.

- A school in the Hanau-Wolfgang district is named after her.

- The city of Berlin honored Elisabeth Schmitz with a plaque at the Beethoven High School in Barbarastraße 9 in Berlin-Lankwitz .

- She is commemorated in the film Elisabeth von Hanau by the documentary filmmaker Steven D. Martin.

Berlin memorial plaque , Barbarastraße 9, Berlin-Lankwitz

Memorial plaque, Auguststrasse 82, Berlin-Mitte

Works

- Memorandum “On the Situation of German Non-Aryans” . Typewritten 1935/36.

- First publication of the text of the memorandum (but wrongly under the name Marga Meusel) in: Wilhelm Niemöller (Ed.): The Synode zu Steglitz . Goettingen 1970.

- First publication of the memorandum stating the correct authorship and commenting as well as a biographical sketch on Elisabeth Schmitz by Dietgard Meyer, in: Hannelore Erhart , Ilse Meseberg-Haubold, Dietgard Meyer: Katharina Staritz 1903–1954 . With an excursus on Elisabeth Schmitz. Documentation Volume I, Neukirchen-Vluyn, 1999, (2nd edition 2002), pp. 185–269.

- Facsimile of the memorandum in: Julia Scheuermann: Dr. Elisabeth Schmitz - A resistance fighter of the Third Reich? In: New magazine for Hanau history . Hanau 2010, pp. 198-282.

- Letters:

- Dietgard Meyer: We don't have time to wait. The correspondence between Elisabeth Schmitz and Karl Barth in the years 1934–1966 , in: KZG 22, 2009, 328–374 (misprint: Correspondence begins in 1933)

- Gerhard Schäberle-Königs: And they were unanimously together every day. The way of the Confessing Community Berlin / Dahlem 1937–1943 with Helmut Gollwitzer, Gütersloh 1998, therein letter to Gollwitzer of November 24, 1938, pp. 203ff

- Andreas Pangritz: Now is the day of repentance - and should the church be silent? Elisabeth Schmitz's reaction to the November pogroms 1938 , in Manfred Gailus (ed.): Elisabeth Schmitz and her memorandum against the persecution of the Jews - Contours of a Forgotten Biography (1893–1977), Berlin 2008, therein letter to Gollwitzer of November 27, 1938, p 170f.

- Dietgard Meyer: After the catastrophe: Two letters from Elisabeth Schmitz to Friedrich Meinecke from 1946 . In: Vision and Responsibility. Festschrift for Ilse Meseberg-Haubold . Münster 2004, pp. 139–144.

- Other publications:

- Edwin von Manteuffel as a source on the history of Friedrich Wilhelm IV. Munich, Berlin 1921 (Diss. Phil.).

- A letter from Wilhelm Grimm about his son Hermann . In: Hanauer Geschichtsblätter 20 (1965), pp. 221–226.

- “The noble court and garden of the Lord of Westerfeld” and “Kesselstadt Castle” . In: Hanauer Geschichtsblätter 21 (1966), pp. 97-114.

- Speech to commemorate the victims of fascism, the war victims and the anniversary of the joint meeting of the Bundestag and Bundesrat , on September 7, 1950 . In: German-Jewish literature and culture in class. Communications of the German Association of Germanists, 56th year, No. 3, published by the German Association of Germanists , with Gisela Beste and Ursula Zierlinger. Aisthesis, Bielefeld 2009, ISSN 0418-9426 , pp. 402-407.

literature

- Biographies:

- Manfred Gailus : But it tore my heart - the quiet resistance of Elisabeth Schmitz . Göttingen 1st edition 2010, 2nd edition 2011. ISBN 978-3-52555-008-3

- Sibylle Biermann-Rau: Elisabeth Schmitz. How the Protestant stood up for Jews when her church was silent. Hamburg 2017. ISBN 978-3-946905-04-2

- Further literature:

- Wilhelm Niemöller (Ed.) The Synod of Steglitz. The third Confessional Synod of the Evangelical Church of the Old Prussian Union. Goettingen 1970.

- Gerhard Schäberle-Königs: And they were unanimously together every day. The Path of the Confessing Community Berlin / Dahlem 1937-1943 with Helmut Gollwitzer, Gütersloh 1998

- Andreas Pangritz : The Confessing Church and the Jews. Who was the author of the memorandum “On the Situation of German Non-Aryans” (1935/36)? In: Bonhoeffer-Rundbrief 69, October 2002, pp. 16–37.

- Andreas Pangritz: The late discovery of a witness: the life and work of Elisabeth Schmitz . In: Hermann Düringer, Hartmut Schmidt (Hrsg.): Church and its dealings with Christians of Jewish origin during the Nazi era - putting an end to oblivion . Frankfurt am Main 2004, pp. 132-150.

- Reinhart Staats : Elisabeth Schmitz and charity in the fight against racism , in: ders .: Protestants in German history. Historical theological considerations , Leipzig: EVA 2004, pp. 52–61.

- Marlies Flesch-Thebesius / Manfred Gailus: Different from other Germans. As early as 1935, the Berlin teacher warned against the "extermination" of the Jews . In: Zeitzeichen 9 (2008), No. 4, pp. 19–21.

- Barbara Nagel (Ed.): Buried - but not forgotten. Well-known personalities at Hanau cemeteries . Hanau 2008, p. 138 f .: Dr. Elisabeth Schmitz. Teacher and opponent of the Nazi dictatorship .

- Ursula Zierlinger: "... even the stones scream." (About the memorandum), in German-Jewish literature and culture in class. Announcements of the German Association of Germanists, vol. 56, volume 3. Ed. German Association of Germanists , with Gisela Beste and U. Zierlinger. Aisthesis, Bielefeld 2009, ISSN 0418-9426 , pp. 398-402.

- Sibylle Biermann-Rau: The synagogues were on fire on Luther's birthday - a request. 2nd edition, Stuttgart 2014

- Karsten Krampitz : Everyone is subject , Alibri, Aschaffenburg, 2017, ISBN 978-3-86569-247-4 .

- Claudia Lepp : Marga Meusel and Elisabeth Schmitz. Two women, two memoranda and their path to the culture of remembrance. In: Siegfried Hermle / Dagmar Pöpping (ed.): Between transfiguration and condemnation. Phases of the Reception of Protestant Resistance to National Socialism after 1945 (AKiZ B 67). Göttingen 2017, pp. 285–301.

- Anthology:

- Manfred Gailus (Ed.): Elisabeth Schmitz and her memorandum against the persecution of the Jews. Outlines of a forgotten biography (1893–1977) . Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-88981-243-8 . In this:

- Marlies Flesch-Thebesius: A feeling of strangeness. Correspondence between Elisabeth Schmitz and Karl Barth . Pp. 83-92.

- Manfred Gailus: Elisabeth Schmitz was not a film actress. Great oblivion and late post-war times . Pp. 183-190.

- Manfred Gailus: In the world capital of historicism. Elisabeth Schmitz 'early minting by Adolf von Harnack and Friedrich Meinecke . Pp. 39-53.

- Rolf Hensel: A teacher on the "path of the unconditional". The teacher Elisabeth Schmitz at the Prussian secondary school (1921 to 1938) . Pp. 54-82.

- Hartmut Ludwig: The memorandum by Elisabeth Schmitz “On the situation of German non-Aryans”. Analysis, context comparison . Pp. 93-127.

- Gerhard Lüdecke: A sensational find in Hanau 2004. New perspectives on the biography of Elisabeth Schmitz . Pp. 20-38.

- Dietgard Meyer: "Mother Elisabeth". Biographical introduction to the life and work of Dr. Elisabeth Schmitz . Pp. 11-19.

- Andreas Pangritz: Now is the day of repentance - and should the church be silent? Elisabeth Schmitz's reaction to the November pogroms of 1938 (pp. 163–182).

- Martina Voigt: companion in the resistance. Elisabeth Schiemann's commitment to equal rights for Jews . Pp. 128-162

- Manfred Gailus / Clemens Vollnhals (eds.): With heart and mind - Protestant women resisting Nazi racial politics , Göttingen 2013.

- Manfred Gailus (Ed.): Elisabeth Schmitz and her memorandum against the persecution of the Jews. Outlines of a forgotten biography (1893–1977) . Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-88981-243-8 . In this:

-

New magazine for Hanau history . In this:

- Hubert Zilch: Elisabeth Schmitz - A courageous woman in bad times . In: New magazine for Hanau history . 2/2002, pp. 109-111.

- Claudia Schmid-Rathjen, Dietgard Meyer: "Elisabeth Pusto" in Wandlitz - on the trail of Elisabeth Schmitz . In: New magazine for Hanau history . Hanau 2008, pp. 130-224.

- Julia Scheuermann: Dr. Elisabeth Schmitz - A resistance fighter of the Third Reich? In: New magazine for Hanau history . Hanau 2010, pp. 259–282.

- Peter Loewenberg: About Elisabeth Schmitz . In: New Magazine for Hanau History , 2014, pp. 202–205.

- Margot Käßmann : On the 120th birthday of Dr. Elisabeth Schmitz . In: New Magazine for Hanau History , 2014, pp. 207–215.

Web links

- Literature by and about Elisabeth Schmitz in the catalog of the German National Library

- Sibylle Biermann-Rau: Elisabeth Schmitz. Solidarity with the Jews, critical of their Confessing Church on Frauen-und-reformation.de

- "Resistance!? Evangelical Christians under National Socialism "

- Database entry at yadvashem.org

- Dietgard Meyer: Elisabeth Schmitz. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 27, Bautz, Nordhausen 2007, ISBN 978-3-88309-393-2 , Sp. 1250-1256.

Individual evidence

- ^ Elisabeth Schmitz: Edwin von Manteuffel as a source for the history of Friedrich Wilhelm IV., Munich . Berlin 1921 (Diss. Phil.).

- ^ Wolfgang Keim: Education under the Nazi dictatorship . Vol. 2, 2nd edition Darmstadt 2005, ISBN 3-534-18802-0 , p. 42.

- ↑ Flesch-Thebesius.

- ↑ An original copy is e.g. B. in the Hessian main state archive Wiesbaden .

- ↑ Manfred Gailus : Elisabeth Schmitz fought against the Nazi regime. Protestant protestant. In: Evangelische Zeitung , issue 11 K, March 16, 2014, p. 8.

- ↑ Corniceliusstrasse 16

- ↑ a b Eckhard Meise : Elisabeth Schmitz - The Hanauer Years . In: New magazine for Hanau history . Hanau 2008, pp. 259-282.

- ↑ Werner Kurz: Resistance out of the Christian spirit. A film by the American pastor Steven D. Martin illuminates the life and work of Elisabeth Schmitz . In: Hanauer Anzeiger , November 8, 2008, p. 19.

- ↑ Dietgard Meyer. In: Erhart, Meseberg-Haubold, Meyer, (Ed.), P. 245.

- ↑ See: Niemöller: Kampf, p. 455; ders .: The Synod, pp. 29–58: Reprint of the memorandum with the incorrect author's statement “Marga Meusel”.

- ↑ Role models. Elisabeth Schmitz tirelessly urged her church to help the Jews against their disenfranchisement. Your resistance is almost forgotten. In: chrismon. 05/2009

- ↑ http://www1.yadvashem.org/yv/en/righteous/pdf/righteous_october_2011.pdf or http://www1.yadvashem.org/yv/en/righteous/pdf/virtial_wall/germany.pdf .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Schmitz, Elisabeth |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German Protestant theologian and resistance fighter |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 23, 1893 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Hanau |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 10, 1977 |

| Place of death | Offenbach am Main |