Air War in World War II

The aerial warfare in World War II spanned the period from September 1, 1939 ( invasion of Poland ) to September 2, 1945 ( Japan surrender ). Goals were

- To achieve and use air superiority ,

- Destroy the enemy’s military installations and infrastructure,

- To sink the enemy's naval forces - ships and submarines -

- Sinking supply-carrying merchant ships,

- to demotivate / demoralize the population.

In the course of the Second World War , attacks against industrial sites and civilians increased in intensity and number. At the latest with the beginning of the Battle of Britain , air defense became a focus of the air war .

A constant task of the air forces of the warring states was the close air support of the ground troops with simultaneous lockdown of the battlefield (see also Combat of Combined Arms ).

The war from the air: theories and first approaches

As early as the First World War , the new aerial warfare was of growing importance. The development of military aircraft made great strides during these years.

In addition to the operational use of aircraft over the front area for reconnaissance or ground support purposes , strategic bombing attacks were also carried out. The attacks by the Allies were mainly aimed at the industrial area of Lorraine and Luxembourg , while the German bombers attacked cities like Paris or London more directly .

After the war, the military tried to draw conclusions for future warfare. The theories of the Italian general Giulio Douhet , which he published in his book Dominio dell'Aria in 1921, proved to be very influential . Based on the widespread belief that a new war would require the mobilization of all forces of a state to an even greater extent, he said that the sources of strength, i.e. the deep hinterland of the enemy, must now be the main targets of attack. He advocated first eliminating the opposing air forces and then attacking the large centers and cities in order to reduce the enemy's resilience by damaging industries and demoralizing the population. This would force the enemy state to surrender, in which case the example of the German Empire of 1918 was evidently a model for it. The attack on the morale of the opposing population was clearly in the foreground with Douhet: "I even consider it permissible and meritorious to bomb inhabited cities with poison gas bombs ." On land and at sea, however, one should limit oneself to defense.

These proposals were hardly regarded as serious instructions for action (as was the case in the German Reich), but they indicated the direction of a new development. The British armed forces were most likely to respond to the idea of strategic bombing. The influential British military theorist Basil Liddell Hart pointed out how effective blows against the enemy command system could be: "If such a blow is delivered sufficiently quickly and powerfully, there is no reason why not in a few hours - or at most days - After the start of the hostilities, the nervous system of one of the fighting countries should be paralyzed. ”So the focus here was not on terrorizing the civilian population, although the British had also gained experience in 1922 in Iraq (then British mandate Mesopotamia ).

Course of war

Poland (1939)

At the beginning of the Second World War, the Luftwaffe had 1,180 combat aircraft: 290 Ju 87 dive bombers, 290 bombers (mainly He 111 ), and 240 naval aviators. In total, Germany owned around 3,000 aircraft, two thirds of which were modern.

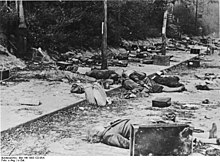

In the early morning of September 1, 1939, during the German air raid on Wieluń, the militarily insignificant Polish town of Wieluń was largely destroyed and an estimated 1,200 people were killed. The attack is considered by historians to be the first war crime to be committed during the raid .

The expectation of the Wehrmacht High Command to achieve clear air superiority over Poland during the attack on Poland was fulfilled right at the beginning of the offensive. Nevertheless, the German Air Force had to record surprisingly high losses in combat aircraft. 22% of the German fighter planes were destroyed by the end of the campaign. Not least for this reason, the attack date for the western campaign had to be postponed 29 times.

Western Europe

The Belgian Air Force had about 192 and the Dutch Air Force 155 machines.

On the German side there were about 900 single-engine fighters ( Bf 109 ), about 220 twin-engine fighters (so-called destroyers ; Bf 110 ), about 1100 twin-engine bombers, mainly He 111 and Do 17 , 450 three-engine Ju 52 transport aircraft , a small number of twin-engine ( Ju 88 ), about 320 single-engine dive bombers ( Ju 87 ), about 45 single-engine biplane attack aircraft ( Hs 123 ) and a small number of other models.

The losses in the western campaign were also unexpectedly high. In Holland, on May 10, 1940, the Air Force lost 274 Ju-52 transport aircraft in one day, a world record. In total, the Air Force lost over 2,000 machines in Holland in five years.

Every major offensive by the German armed forces was initially initiated by heavy bombardment by the Luftwaffe. Stukas were usually used here. For example, on May 10, when the German attack began, or as part of the Sedan tank breakthrough a few days later. These air strikes during the western campaign were sometimes so successful that Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring was convinced that he could defeat the Allies in the Battle of Dunkirk with his air force alone . This miscalculation led, among other things, to the fact that more than 300,000 Allied soldiers were evacuated to Great Britain as part of Operation Dynamo . Due to the short approach routes from their bases in the south of England, the British succeeded time and again in seizing control of the air over Dunkirk and shooting down 156 German aircraft without losing 177 aircraft themselves. Since periods of bad weather also hampered the deployment of the Air Force, Göring's overall balance sheet remained far from his ambitious goal. Nevertheless, the Wehrmacht managed to encircle large parts of the French army by June 17, and finally an armistice was concluded on June 22 .

As with the tank weapon, close cooperation between the German air fleets and the army groups, down to the tactical level, made it possible to ensure rapid and efficient air support and to compensate for the numerical weakness by establishing centers of gravity.

For the day raids on London and other British cities that began on September 7, 1940, see Air raids on cities / Great Britain . With the attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, the air raids on England became considerably less frequent.

One day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the United States declared war on the Japanese Empire; Hitler declared war on the United States on December 11, 1941, although he was not obliged to do so under the Tripartite Pact . The US Air Force (then it was called USAAF ) started air raids against cities in the German Reich in August 1942; since the Allied landing in Normandy, it has been instrumental in the advance on the Western Front .

The Operation Market Garden was an airborne operation of the Allies (17 to 25 September 1944). Due to the high losses on the Allied side, it is now considered the last military success of the Wehrmacht. The aim of the Allies was to use paratroopers to secure a number of bridges in the Netherlands and thus initiate the crossing of the Rhine, which was the last great natural barrier in western Germany. The Nijmegen Waal Bridge was secured; the large Rhine bridge near Arnhem, however, remained in German hands or was destroyed. The British 1st Airborne Division was completely wiped out in the course of the battle.

Balkans / Mediterranean area

North africa

Eastern Europe

Finnish-Soviet Winter War

In the so-called Winter War , which lasted from November 30, 1939 to March 13, 1940, the Soviet Air Force had the air superiority.

Pacific

The war in the Pacific began with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, which involved over 350 aircraft launched from six aircraft carriers belonging to the Kidō Butai . This attack destroyed most of the aircraft stationed on Pearl Harbor and wiped out large parts of the American Pacific Fleet . Three warships were sunk and five were badly damaged. However, only the USS Arizona and the USS Oklahoma were lost for good. The other ships were repaired and were soon available again. The three American aircraft carriers, which were one of the main targets, were at sea, however. At Pearl Harbor, the dock, supply and shipyard facilities could be repaired quickly. In addition, the base tank farms remained undamaged.

The attack united the American public, who now by a large majority demanded the entry of the United States into the war and retaliation for Pearl Harbor. The following day, December 8, 1941, the United States declared war on Japan . Just three days later, the Japanese achieved another important success that they could achieve with land-based fighter planes. They sank the British Force Z on December 10, 1941 with the battleship Prince of Wales and the battle cruiser Repulse .

Air strikes against cities

During the First World War, the bombing of the civilian population by the German zeppelins was still the exception. The aerial warfare of World War II, however, was directed on both sides on a large scale against civilian populations living in cities.

The first cities damaged or destroyed by the aerial warfare were the Polish cities of Frampol , Wieluń and Warsaw . On May 14, 1940, most of the old town was destroyed in the bombing of Rotterdam in 1940 . In Great Britain, the aerial warfare was directed against military targets such as tanks, ships and bases in the first few months. From May 1940 the Royal Air Force Bomber Command attacked German cities with tactical bombing. The climate radicalized in early September 1940 when the German Air Force flew its first attack on a British city (London) (see The Blitz ).

In total, the air strikes that were flown against cities killed 60,595 British civilians and between 305,000 and 600,000 German civilians. The American air raids against Tokyo , Yokohama, Kobe, Nagoya and other Japanese cities (see Airstrikes on Japan ) and the atomic bombing killed roughly between 330,000 and 500,000 Japanese. The Royal Air Force was able to use more bombers than the Luftwaffe as early as 1941.

The creation of so-called firestorms over German cities was considered a success by the British. In order to start a firestorm, it was not just about dropping the highest possible bomb load (for example, a firestorm never occurred over Berlin), but also the type, sequence and impact location of the bombs. First of all, the roofs were covered with explosive bombs and air mines ("apartment block crackers") and the window panes were made to burst, in order to expose combustible material and to enable the oxygen supply for the stick incendiary bombs . In addition, after about 15 minutes, further explosions of high-explosive bombs with time fuses followed in order to prevent the fire brigade and fire-fighting teams from leaving the shelters and to enable individual fires to merge into “firestorms”. The British had learned this lesson during the Luftwaffe Blitz .

The evaluation of air strikes on cities during the Second World War is controversial under international law . Article 25 of the Hague Land Warfare Regulations prohibits “ attacking undefended cities, living quarters and buildings ”, but it is questionable whether the presence of anti-aircraft batteries already represents a defense in this sense. A commission set up by the US military found that with the establishment of an air defense, no city would be "undefended". In addition, it is questionable whether the provisions of the Hague Land Warfare Regulations were even applicable to air warfare.

The author WG Sebald played a key role in sparking the discussion in Germany on this topic with his paper Luftkrieg und Literatur , published in 1999 .

The historian Gerd R. Ueberschär , on the other hand, describes air attacks such as the bombing of Dresden as "militarily senseless and not covered by the general rules of international martial law". Thomas Widera from the Hannah Arendt Institute for Totalitarian Research at the Technical University of Dresden questions whether Ueberschär's account of the “complexity of historical processes is sufficiently taken into account” . The historians Götz Bergander , Helmut Schnatz , Frederick Taylor , and Matthias Neutzner take a more differentiated look at the question of whether the area bombing of German cities represents a war crime in a complex historical context. Neutzner, Hesse and Reinhard explain that no internationally binding law on air warfare guaranteed the protection of civilians. Taylor deliberately leaves the answer open for the Dresden example . In his works, Neutzner in particular deals intensively with the dictum-grading, dramaturgical elements of such representations, which he calls “constants” of a “collective narrative”. He contests many traditional accounts that describe the attacks on Dresden as the “sudden”, “unexpected”, “senseless destruction” of a “unique” and “innocent” city, “shortly before the end of the war”.

Area bombing was explicitly banned only in 1977 with the additional protocols to the Geneva Convention ratified by Great Britain and Germany .

The moral bombing of the civilian population was outlawed and discussed at all times - even during the war. The Allies assured in their propaganda that the air strikes were aimed exclusively at industries. The National Socialist propaganda, in turn, declared that the German air strikes were “only” retaliatory measures; one would never have extended the fight to non-combat areas on one's own initiative.

“Apart from Essen, we have never chosen a special industrial plant as a destination. The destruction of industrial plants always appeared to us as a kind of special bonus. Our real goal was always the city center. "

German Empire

See also: Economic aspects of the strategic bombing of Germany in World War II

The attacks by the Royal Air Force (RAF) on German cities began with the attack on Wilhelmshaven on September 4, 1939 (see table). The first large-scale bombardment of a major German city took place a few months later on the night of May 15-16, 1940 on Duisburg . In the operation Razzle the German grain harvest was trying to destroy by mass dropping of fire platelets.

Attack technique

After the loss-making aerial battle over the German Bight , the RAF switched to flying thousand bomber attacks on German cities at night . Military targets were rarely attacked. The railways to the concentration camps were not attacked . Almost all large and medium-sized cities were destroyed on a large scale. Spared z. B. Breslau , Schwerin, Göttingen, Goslar, Lüneburg, Lüdenscheid, Konstanz, Marburg (Lahn), Görlitz, Zwickau, Erfurt (partially destroyed), Recklinghausen (partially destroyed), Halle (Saale) (partially destroyed) and Heidelberg ; in Heidelberg the Americans wanted to set up their headquarters after the victory.

strategy

The British strategy of " moral bombing " was to break the morale of the population; confidence in the German government and the hope of a final German victory were to be weakened. The population should be threatened by the loss of their material livelihood, so that they are deterred from their professional activity as much as possible. It was believed that people who lost their homes in a bombing night would not go to work (e.g. in an armaments factory) in the next few days.

Many incendiary bombs were used, which had a devastating effect on the residential areas of the bombed cities. Incendiary bombs such as the electron thermite rod incendiary bomb had been designed and tested long before the war.

Arthur Harris , known in the German population as "Bomber Harris", had the idea of flying a thousand bomber attacks ( bomber stream ). This should maximize the effect on the target; In addition, excessive demands on the German night fighter control system and the German air defense (flak) should keep the British casualty rate (s) as low as possible.

At the beginning of 1943 the Allies decided at the Casablanca Conference to initiate a " combined bomber offensive " against the German Reich. The 'German military, industrial and economic system' should be attacked, as well as the perseverance of the civilian population. The Americans relied on daytime attacks which, together with the British nighttime attacks, enabled "round-the-clock bombing". As a result, the bombing war intensified significantly, despite the need to temporarily pursue other goals: support of the ground forces during Operation Overlord , defense against the German V-weapons offensive as part of Operation Crossbow . The bombing war reached unprecedented proportions by the end of the war.

From 1943, exact location sketches and production figures of steelworks, tank, weapon, ball-bearing and aircraft factories as well as V-rocket manufacturing plants were sent to Allied general staffs by the resistance group around chaplain Heinrich Maier ; this enabled precise air strikes, whereby residential areas were spared. The Allies used information from German resistance circles, but the Allies had no intention of supporting the internal German resistance; Such support could have consisted in sparing cities with known resistance actions, i.e. not bombing them with air strikes.

From the summer of 1943, the Allies targeted the German armaments and aircraft industries, such as the Messerschmitt factory with the production of the most important German fighter aircraft Bf 109 in Augsburg and Wiener Neustadt . In doing so, they increasingly achieved air sovereignty and forced the German leadership to decentralize arms production at great expense and expense or to move it underground. From this point on, the war was de facto lost for Germany.

Defense measures

As protective measures, large anti-aircraft towers and bunkers were built in large cities in Germany and children and mothers with babies were evacuated from urban centers as part of the children's area .

Table of bombed cities

| city | attacker | First attack | Heaviest attack | Objectives, degree of destruction | Bomb load (t) | dead | items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aachen | Royal Air Force (RAF) | July 1941 | April 11, 1944 | 65% of the living space destroyed | more than 2600 | ||

| Anklam |

USAAF / RAF Air Force |

October 9, 1943 | 4th August 1944 | Arado branch , airfield, old town 80% destroyed | 800 | ► | |

| Aschaffenburg | USAAF | March 1945 | |||||

| augsburg | RAF / USAAF | 17th August 1940 | 25./26. February 1944 | Main focus on the industrial plants of MAN and Messerschmitt . 24% of the housing stock completely destroyed, large parts of the historic city center destroyed. | 1499 | ► | |

| Bad Oldesloe | Royal Air Force (RAF) | April 24, 1945 | Focus: especially the train station overcrowded with refugees | more than 700 | |||

| Bayreuth | RAF / USAAF | January 1941 | April 11, 1945 | Focus on the city center and the station district with the textile industry. The city's degree of destruction was 38%. | |||

| Bebra | USAAF | 4th December 1944 | The main focus was the Bebra train station | 64 | ► | ||

| Berlin | RAF / USAAF Soviet Air Force |

August 25, 1940 | March 18, 1945 | The focus was on the city center within the Berlin Ringbahn | 68,285 | ≈20,000 |

► ► |

| Bielefeld | RAF | June 1940 | September 30, 1944 | Most of the old town destroyed | 1347 | ||

| Bingen am Rhein | USAAF | September 29, 1944 | December 29, 1944 | Main objective of the Bingerbrück marshalling yard, around 96% of the urban area destroyed |

|||

| Bochum | 38% of the city destroyed | 11,177 | ► | ||||

| Boeblingen | RAF / RCAF / RAAF | 7th / 8th October 1943 | 7th / 8th October 1943 | 90% severe and light damage. | 60 | ||

| Bonn | October 18, 1944 | Degree of destruction of the buildings at 30% | about 1500 | ||||

| Brandenburg on the Havel | RAF / USAAF | August 6, 1944 | March 31, 1945 |

Opel truck plant ; Arado total Urban area destroyed to 15% |

|||

| Braunschweig | RAF | 17th August 1940 | October 15, 1944 |

BMA ; Franke & Heidecke ; Voigtländer ; MIAG ; Luther Works ; NEVER ; Selwig & Lange inner city to 90%, entire city to 42% destroyed |

847 (October 15, 1944 only) |

≈1000 (only October 15, 1944) |

► |

| Bremen | RAF | May 18, 1940 | 18./19. August 1944 |

Atlas , AG Weser , Vulkanwerft , Borgward , Hansa-Lloyd and Goliath -Werke, Focke-Wulf ges. City area destroyed to 62%, the Stephaniviertel in the center to over 95% |

1120 | 1050 | ► |

| Bremerhaven | RAF | September 18, 1944 | September 18, 1944 | total 57% of the urban area destroyed | 900 | 618 | ► |

| Wroclaw | RAF | August 7, 1944 | |||||

| Bruchsal | USAAF | March 1, 1945, 2 p.m. | around 96% of the inner city destroyed | ≈1000 | |||

| Chemnitz | RAF / USAAF | May 12, 1944 | March 5, 1945 | Old town destroyed to 95%, total. 75% of the urban area destroyed | 7,700 | 3,600-4,000 |

► ► |

| cottbus | USAAF | October 25, 1940 | February 15, 1945 | Railway facilities, Ind., Southeast Z | about 1000 | > 1000 | ► |

| Danzig | RAF | Industry, infrastructure, mili., Civil. | |||||

| Darmstadt | RAF | 11./12. September 1944 | Old town destroyed to 99%, total. 78% urban area | approx. 750 | 11,500 | ► | |

| Dessau | RAF | March 7, 1945 | total 80% urban area destroyed | 1693 | 668 | ► | |

| Dorsten | RAF | March 14, 1941 | March 22, 1945 | City center destroyed to 95% | 377 | 319 | ► |

| Dortmund | RAF | May 5, 1943 | March 12, 1945 | Downtown 98% destroyed | 4851 | 890 | ► |

| Dresden | RAF / USAAF | October 7, 1944 | 13./14. February 1945 | Ind., Infra., Mili., Civil. 90% of the city center destroyed. | 2660 | 22,700-25,000 | ► |

| Düren | RAF | May 12, 1940 | November 16, 1944 | Infra., Milit., Civil. 99.2% of the urban area destroyed, only four residential buildings were spared | 1945 | 3106 | ► |

| Dusseldorf | RAF | August 1, 1942 | June 12, 1943 | 94% of the inner city destroyed | 18,652 | ► | |

| Duisburg | RAF | May 13, 1940 | 14./15. October 1944 | 80% urban area destroyed | 30,535 | approx. 8,000 - 12,000 | ► |

| Eberswalde | air force | April 26, 1945 |

Ardelt-Werke downtown approx. 50% destroyed |

||||

| Eisenach | USAAF / RAF | February 24, 1944 | September 11, 1944 | BMW - automobile and aircraft engine factory , city 6% destroyed, over 50% damaged | 400 t | 370 civilians dead | ► |

| Emden | RAF | March 31, 1940 | September 6, 1944 | Harbor and North Sea Works , 80% urban area destroyed | ► | ||

| Emmerich on the Rhine | RAF | October 7, 1944 | total Urban area destroyed to 97% | ||||

| Erbach (Odw.) | March 26, 1945 | 39 buildings destroyed, 138 buildings partially damaged, further damage from artillery fire | 26th | ||||

| Erfurt | RAF / USAAF | July 26, 1940 | February 25, 1945 | Industry, infrastructure, airfield, city center, 17% of the apartments totally destroyed | 1100 | 1535 | ► |

| eat | Downtown 90% destroyed. | 36,825 | ► | ||||

| Fallersleben | April 8, 1944 | August 5, 1944 | Two thirds of the Volkswagen factory destroyed | ||||

| Flensburg | RAF / USAAF | 20th August 1940 | May 19, 1943 | Various areas of the city were bombed, in particular the Flensburg harbor with the Flensburg shipyard and the Schäferhaus airfield . Various problems during the air raids meant that the city was largely spared. Due to the attacks, the shipyard's submarine production came to a standstill. | over 30,000 | 176 dead civilians and 119 dead Allied soldiers |

► |

| Frankfurt am Main | RAF / USAAF | June 4th 1940 | March 22, 1944 |

VDM / Heddernheimer Kupferwerk, IG Farben ( Höchst works ), VDO , Adlerwerke Hartmann & Braun , Messer Griesheim old town 98% destroyed, over 50% in the entire city area |

29.209 | 5559 | ► |

| Frankfurt (Oder) | RAF | August 25, 1940 | February 15, 1944 | 93% of the inner city destroyed by air raids and defense | 58 | ► | |

| Freiburg in Breisgau | RAF Air Force |

May 10, 1940 | November 27, 1944 | Downtown, railway systems. 30% of all homes destroyed or badly damaged | ≈3000 |

► ► |

|

| Freital | USAAF | August 24, 1944 | August 24, 1944 |

Voltolwerk of Rhenania-Ossag in Freital-Birkigt, railway facilities in Freital-Potschappel 2000 destroyed and damaged apartments |

262 | ||

| Friedrichroda | USAAF | February 6, 1945 | 74 destroyed and 350 damaged houses | 27.5 | 135 | ► | |

| Friedrichshafen | RAF | April 28, 1944 |

Maybach , cogwheel factory city area destroyed to 75% |

≈2500 | ► | ||

| Fulda | RAF / USAAF | July 20, 1944 | September 11, 1944 | The production facilities of Fulda Reifen , the Bellinger enamelling works and several other companies were completely destroyed. Among the dead were around 350 forced laborers from the Mehler company , who died when all entrances had been hit by the Krätzbach tunnel, which was developed as a shelter. | 1,600 | ► | |

| Fuerth | USAAF / RAF | August 16, 1940 | February 25, 1944 | mainly industry, otherwise z. T. false drops in attacks on Nuremberg; 6% total losses, 30% serious u. Medium damage to the building stock | approx. 390 | ► | |

| Gelsenkirchen | November 6, 1944 | Destruction of 52% of the houses, 42% are damaged. 6% can still be lived in. 28% of the industrial plants are destroyed. | 22,885 | about 3000 | ► | ||

| Gera | USAAF | May 12, 1944 | April 6, 1945 | Industry, railway systems, downtown | 550 | 550 | ► |

| to water | RAF | December 6, 1944 | The city was 67% destroyed, the inner city 90%. | 813 | |||

| Gotha | USAAF | February 24, 1944 | February 6, 1945 | Industry, rail, downtown | over 890 | over 550 | ► |

| Goettingen | July 7, 1944 | April 7, 1945 | Railway systems. City destroyed by 2.1% (235 apartments, 59 residential buildings) | 107 | ► | ||

| Graz | USAAF | August 1943 | February / March 1945 | Railway and industrial facilities. 7733 buildings, 8999 apartments destroyed; the historic old town was largely spared | ≈1800; the number of victims is comparatively low due to the large air raid shelter in the Schloßberg. | ||

| Gross-Gerau | RAF | 25./26. August 1944 | Downtown, 230 houses destroyed, 300 others damaged. City church burned down, 1000 people homeless. | 28 | |||

| Gutersloh | USAAF | 1940 | November 26, 1944 | 290 | |||

| Hagen | RAF / USAAF | May 15, 1940 | March 15, 1945 | Marshalling yard lobby , AFA , inner city almost completely destroyed by several attacks. | ≈2200 | ► | |

| Halberstadt | USAAF | April 8, 1945 | Junkers branch ; 82% of the inner city was destroyed. | ≈2500 | ► | ||

| Halle (Saale) | USAAF | July 7, 1944 | March 31, 1945 | 3,600 buildings, 13,000 apartments destroyed | 2,593 | > 1284 | ► |

| Hamburg | RAF / USAAF | May 18, 1940 | 27./28. July 1943 | City center destroyed to 80%, urban area to 60%. | 2439 | ≈35,000 | ► |

| Hamm | RAF / USAAF | 1940 | April 22, 1944 | Hamm marshalling yard , Westphalian wire industry , Westphalian Union , port , barracks, the entire urban area and the immediate vicinity of Hamm, especially mining in Bockum-Hövel , Herringen , Pelkum , Heessen , Ahlen . Destruction of the Hamm urban area 60–80%. | 1029; including 233 prisoners of war, internees and forced laborers | ► | |

| Hanau | RAF | 1944 | March 19, 1945 | Old town 90%, urban area 80% destroyed. | ≈2250 | ► | |

| Hanover | RAF / USAAF | May 19, 1940 | October 9, 1943 |

Continental-Werke , Hanomag / MNH , AFA , Deurag / Nerag , 52% of all buildings destroyed in the city center 90% |

1670 | 6782, of which 4748 inhabitants | ► |

| Heidelberg | 1944 | 1945 | Only minor damage, city almost intact | ||||

| Heilbronn | RAF | December 16, 1940 | 4th December 1944 | Ind., Infra., Mili., Civil. Downtown completely except for 3 houses, a total of 5,100 of 14,500 buildings destroyed | ≈6500 | ► | |

| Herne | Building fabric in Herne largely spared | 419 | ► | ||||

| Hildesheim | RAF / RCAF / USAAF | July 29, 1944 | March 22, 1945 | Freight yard ; Sugar refinery ; VDM -Halbzeugwerke GmbH ("Metallwerk Hildesheim"); Sinking mechanism ; E. Ahlborn AG ; Old town destroyed to 90% | 1060 | 1511 1736 |

► |

| Homburg | RAF / USAAF | March 14, 1945 | 220 | ||||

| Ingolstadt | USAAF | January 15, 1945 | April 9, 1945 | ≈650 | ► | ||

| Jena | RAF / USAAF | May 27, 1943 | March 19, 1945 |

Zeiss and Schott plants, inner city badly affected |

1,025 | ≈800 | ► |

| Jülich | RAF | November 16, 1944 | total Urban area destroyed to 97% | ||||

| Kaiserslautern | RAF / USAAF | September 3, 1941 | September 28, 1944 | In several major attacks in 1944/45, almost two thirds of the city center was destroyed. During the reconstruction, much of the remaining building fabric was torn down in order to obtain openings and widen the streets. | ≈350 | ||

| Karlsruhe | RAF | Depending on the calculation basis, 24–38% destroyed | 10,598 | 1754 | |||

| kassel | RAF | October 22, 1943 |

Henschel & Son ; Fieseler works ; MWK city area to 80%, old town to 97% destroyed. |

circa 1400 | approx. 7000 | ► | |

| Kiel | 2nd July 1940 | 3rd / 4th April 1945 | Large shipyards on the east bank of the fjord : DWK , Germaniawerft , Howaldtswerke . 35% of the buildings (40% of the apartments) destroyed | 29.202 | 2515 | ► | |

| Koblenz | RAF | November 6, 1944 | total 87% of the urban area destroyed | 1016 | ► | ||

| Cologne | RAF | June 18, 1940 | March 2, 1945 | At the end of the war, 95% of the old town had been destroyed. | 48,041 | ► | |

| Königsberg (Prussia) | Soviet Air Force / RAF | June 22, 1941 | 26./27. August 1944 and 29./30. August 1944 | Historic city center (old town, Kneiphof, Löbenicht) almost completely destroyed | over 480 | ≈6000 | ► |

| Krefeld | June 18, 1940 | 2nd / 3rd October 1942 | u. a. Steel works, considerable destruction in Uerdingen : wagon factory , Hohenbudberg shunting yard , Weiler-ter Meer chemical factory ( IG Farben ) |

||||

| Landau in the Palatinate | USAAF | 1944 | 1945 | 586 | |||

| Landshut | USAAF | December 1944 | March 19, 1945 | railway station | ≈400 | ||

| Leipzig | RAF | March 27, 1943 | December 4, 1943 | Up to 60% of the building fabric destroyed, 40% of the apartments | about 500 | ≈1800 | ► |

| Leverkusen | June 5, 1940 | October 26, 1944 | Great destruction | ||||

| Linz | RAF / USAAF | 1944 | 1945 | 1679 | |||

| Ludwigshafen am Rhein | RAF | October 1941 | January 5, 1945 | total City area destroyed to over 80%, main target BASF | > 500 | ► | |

| Lübeck | RAF | March 28, 1942 | March 28, 1942 | Old town destroyed to 30% | 400 | 320 | ► |

| Magdeburg | RAF | January 16, 1945 |

BRABAG ( Rothensee ); Krupp-Gruson ; Buckau Wolf old town 90% destroyed |

about 1200 | ≈2,500 | ► | |

| Mainz | RAF | 1942 | February 27, 1945 | total 80% urban area destroyed | ≈1200 | ► | |

| Mannheim | June 1, 1940 |

Motorenwerke Mannheim (MWM); Daimler-Benz plant, urban area almost completely destroyed |

25.181 | 2171 | ► | ||

| Meiningen | USAAF | September 13, 1944 | February 23, 1945 | Infrastructure repair shop |

approx. 219 | ≈220 | ► |

| Mülheim an der Ruhr | RAF | 22./23. June 1943 | 29% of the total stock destroyed | ► | |||

| Munich | RAF / USAAF | Summer 1942 | February 7, 1945 | BMW - aircraft engine plant Allach and main plant Milbertshofen , entire city 50%, old town 90% destroyed. | 27.111 | 6500 | ► |

| Mönchengladbach | RAF / USAAF | May 12, 1940 | Both cities ( M. Gladbach and Rheydt ) about 65% destroyed | approx. 2000 | |||

| Muenster | RAF / USAAF | May 16, 1940 | March 25, 1945 | About 91% of the old town and 63% of the entire city were destroyed. | > 1600 | ||

| Neuss | RAF | July 31/1. August 1942 | Large parts of the historic old town destroyed | ||||

| Nordhausen | USAAF / RAF | 4th July 1944 | April 3 and 4, 1945 | total Approx. 74% of the urban area destroyed | 2,700 | ≈8800 | ► |

| Nuremberg | RAF | 21./22. December 1940 | January 2, 1945 | Railway systems and industry south of the city center ( marshalling yard , MAN , Schuckert , Victoria ) Old town almost completely destroyed |

2300 | 1800 | ► |

| Oberhausen | 31% of the total stock destroyed | 2300 | ► | ||||

| Oldenburg | Oldenburg altogether 1.4% (130 houses) destroyed | ► | |||||

| Offenbach am Main | RAF | December 20, 1943 | March 18, 1944 | A total of 36% destroyed, primarily the old and western towns | 467 (for all attacks) | ► | |

| Oranienburg | USAAF | March 6, 1944 | March 15, 1945 | Goods station, Heinkel aircraft factory, Auerwerke (nuclear research), city area destroyed to 70% | (20,000 bombs) | 2,000 (including approx. 1,000 concentration camp prisoners) | [1] |

| Osnabrück | RAF | June 20, 1942 | September 13, 1944 | Railway depot , marshalling yard , Klöckner steel works , OKD (copper and wire works), 94% of the old town destroyed, 65% of the entire city area | ► | ||

| Paderborn | RAF | January 17, 1945 | March 23, 1945 | total City area destroyed to 85% | |||

| Peenemünde | RAF | August 18, 1943 | Army Research Center , Experimental Station of the Air Force , sleeping and living quarters | 1874 | 735 | ► | |

| Pforzheim | RAF | April 1, 1944 | February 23, 1945 | total 83% of the urban area destroyed | 1575 | ≈18,000 | ► |

| Pirmasens | RAF | August 9, 1944 | March 15, 1945 | Two thirds of the urban area destroyed, 90% of the inner city | ≈500 | ||

| Plauen | USAAF, RAF | September 12, 1944 | April 10, 1945 | over 75% of the urban area destroyed | 4,925 | over 2,358 | ► |

| Poses | RAF | May 29, 1944 | Focke-Wulf , AFA -Akkumulatorenwerk | ||||

| Potsdam | RAF | April 14, 1945 | Up to 97% of the residential buildings in the city center and the Berlin suburbs were destroyed | 1,700 | 1,593 | ► | |

| Rees | RAF | May 10, 1940 | February 16, 1945 | total 76% of the urban area destroyed | |||

| regensburg | RAF, USAAF | Messerschmitt aircraft factory , railway facilities, Regensburg harbor ; only minor damage in the old town itself | about 3000 | ||||

| Remscheid | RAF | July 31, 1943 | total 82% of the urban area destroyed | ||||

| Rosenheim | USAAF | October 20, 1944 | April 18, 1945 | railway station | 53 (April 18, 1945 only) |

► | |

| Rostock | RAF | June 11, 1940 | 24./27. April 1942 | Downtown half destroyed. | 617 | ► | |

| Rothenburg ob der Tauber | USAAF | March 31, 1945 | March 31, 1945 | 9 | 39 | ► | |

| Saarbrücken | RAF | Late July 1942 | October 5, 1944 | Old Saarbrücken almost completely destroyed | about 1000 | about 400 | ► |

| Salzburg | USAAF | October 16, 1944 | May 1, 1945 | 40% of the buildings damaged or destroyed | 1500 | 547 | ► |

| Schmalkalden | USAAF | July 20, 1944 | February 6, 1945 | Railway, city | 88 civilians | ► | |

| Schweinfurt | USAAF, RAF | August 17, 1943 | February 24, 1944 | a total of 22 air raids destroyed 40% of the city and 45% of the industrial area | 1079 | ► | |

| Solingen | RAF | 4th / 5th November 1944 | 2.5 km² city center completely destroyed | 1882 | ► | ||

| Szczecin | 1944 | ||||||

| Stralsund | USAAF | October 6, 1944 | 248 | ≈800 | ► | ||

| Stuttgart | RAF | August 25, 1940 | September 12, 1944 | A total of 53 air raids between 1940 and 1945 destroyed 68% of all buildings in the entire city | approx. 670 | ≈1000 | ► |

| Swinoujscie | USAAF | March 12, 1945 | 1609 | 8,000 to 23,000 (refugees) | ► | ||

| trier | RAF | December 19, 1944 | December 23, 1944 | 41% urban area destroyed, focus on the old town | 420 | ||

| Ulm | RAF | December 17, 1944 |

Magirus - Deutz old town destroyed to 81% |

707 (on December 17, 1944) |

► | ||

| Weimar | USAAF | August 24, 1944 | February 9, 1945 | Industry, downtown | 965 | over 1,850 | ► |

| Wesel | RAF | February 16, 1945 | February 19, 1945 | total Urban area destroyed to 97% | ► | ||

| Vienna | RAF / USAAF | March 17, 1944 | March 12, 1945 | 28% building damage | 8796 | ► | |

| Wiener Neustadt | RAF / USAAF | 1944 | 1945 |

Wiener Neustädter Flugzeugwerke Raxwerke |

► | ||

| Wiesbaden | RAF | August 1940 | 2nd / 3rd February 1945 | 22.3% of the apartments destroyed | circa 1700 | ||

| Wilhelmshaven | RAF | September 4, 1939 | October 15, 1944 | total City area (at the end of the war 60% of the living space destroyed), Kriegsmarine shipyard | 435 | ||

| Wismar | RAF | 1942 | April 14, 1945 | ||||

| Worms | RAF / USAAF | June 20, 1940 | February 21, 1945 | Downtown, industrial and railway facilities | total approx. 700 | ► | |

| Wurzburg | RAF | February 1942 | March 16, 1945 | 82% of the entire city area, over 90% of the old town destroyed | 977 | ≈5000 | ► |

| Wuppertal | RAF | May 1943 | 29./30. May 1943 and 24./25. May 1943 | Wuppertal-Barmen and Wuppertal-Elberfeld - 38% of the entire city area destroyed | 5219 | ► | |

| Xanten | RAF | February 10, 1945 | |||||

| Zerbst | USAAF | April 16, 1945 | total 80% urban area destroyed | at least 574 | |||

| Zweibrücken | RCAF | March 14, 1945 | City area destroyed to 80%, old town almost completely destroyed | ≈200 | ► |

Loss of the population

All in all, up to 600,000 civilians fell victim to the Allied bombing: Seriously wounded survivors of the attacks were part of the one and a half million war invalids in the post-war period .

Air Force losses

Not all of the aircraft that crashed were recovered. Through private initiative, crashed aircraft were discovered in 2015 and the remains of aircraft crews were recovered.

Loss of infrastructure and building fabric

An inventory of the effects of the attacks was carried out at the end of the war by US flights, which systematically documented the German area with aerial photographs : 2013 trolley missions from May 7th to 12th 1945. Small groups of three aircraft each flew precisely defined routes.

France

| city | attacker | First attack | Heaviest attack | aims | Bomb load (t) | dead | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brest | |||||||

| Caen | |||||||

| Calais | February 1945 | ||||||

| Dunkirk | 1940 | ||||||

| Le Havre | RAF | 5th / 6th September 1944 | 340 machines each | approx. 5000 | |||

| Lorient | |||||||

| Paris | Wehrmacht, Air Force | August 26, 1944 | Urban area (593 buildings were destroyed or damaged) | 50 machines | 213 (also 914 wounded) | The attack followed the surrender of the German Wehrmacht commander General Choltitz to the French Colonel Rol-Tanguy. | |

| Royan | RAF | January 5, 1945 | Urban area (90% destroyed) | 1580 (340 machines) | about 800 | ||

| USAAF | April 15, 1945 | German fortifications (city area 100% destroyed) | approx. 1000 (830 machines) | approx. 1300-1700 | Operation Vénérable - first napalm deployment in Europe | ||

| Saint-Nazaire | |||||||

| Strasbourg |

Great Britain

The first wave of German attacks on British cities - known as The Blitz in English-speaking countries - took place from September 1940, when cities were attacked in addition to airfields during the Battle of Britain , and lasted until May 1941, when most of the Luftwaffe's combat units were in preparation for the Campaign against the Soviet Union were withdrawn to the east. In addition to London , the main targets of the attack were primarily important port and industrial cities.

Unlike in major German cities, there were very few air raid shelters in London . Therefore, the people of London sought refuge in the tunnels and stations of the London Underground . An ammunition factory was operated in a tunnel and an underground station was also used for cabinet meetings.

As early as mid-September 1940, the inferiority of the German Air Force became apparent. The aerial combat over English territory went to the substance of the German air force. In order to be able to fly back after a dogfight, only 15 minutes of fighting time remained, otherwise the limited tank filling of the Messerschmitt fighter pilots was running out. Downed or emergency landing pilots were captured, while British pilots were mostly ready for action again on the same day. On the morning of September 17, Hitler postponed the invasion of England (“ Operation Sea Lion ”) for “indefinitely”, on October 12th General Field Marshal Keitel announced: “The Fuehrer has decided that from this day until spring [1941] the preparations should begin. Sea lion 'are only to be continued for the purpose of continuing to put England under political and military pressure. ”Due to high losses, the day attacks were suspended from October 29, 1940, apart from a few attacks with bombers and fighter bombers. The night raids continued until May 1941.

In retaliation for the devastating British air raid on Lübeck on 28/29. In March 1942, the German Air Force launched a series of attacks on English cities with cultural and historical significance from April to June 1942, the so-called Baedeker attacks (English: Baedeker Blitz ).

A brief resumption of the bombing war against British cities, mainly against London, by the Air Force took place from January to May 1944 as part of the " Capricorn Operation ". With its limited and steadily dwindling forces, the Luftwaffe did not succeed in achieving the effect Hitler intended on the morale of the British population. Lack of success and high losses caused the attacks to cease. The only remaining hope of implementing the German retaliatory intentions was the so-called "V-Waffen-Offensive", which began in June 1944, with the V1 and V2 retaliatory weapons .

| city | attacker | First attack | Heaviest attack | aims | Bomb load (t) | dead | items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barrow-in-Furness | air force | September 1940 | May 1941 | Shipyards | |||

| Bath | air force | April 25, 1942 | historic downtown | ► | |||

| Belfast | air force | April 15, 1941 | Industry, shipyards, urban area | about 1000 | ► | ||

| Birmingham | air force | August 9, 1940 | Industry, urban area | 2000 | 2241 | ||

| Brighton | air force | July 1940 | September 14, 1940 | u. a. Railway systems | 198 | ||

| Bristol | air force | November 24, 1940 | Port, aircraft industry, urban area | 919 | 1299 | ||

| Canterbury | air force | May 31, 1942 | historic downtown | ► | |||

| Cardiff | air force | 3rd July 1940 | January 2, 1941 | Port, industry | 355 | ||

| Clydebank | air force | 13-15 March 1941 | Shipyards, ammunition industry | 528 | |||

| Coventry | air force | November 14, 1940 | Defense industry, urban area | 1236 | ► | ||

| Exeter | air force | April 23, 1942 | historic downtown | ► | |||

| Greenock | air force | 6./7. May 1941 | Shipyards | 280 | |||

| Hull | air force | June 19, 1940 | Docks, industry 95% of buildings damaged or destroyed |

about 1200 | |||

| Liverpool | air force | 1-7 May 1941 | Port, industry, urban area | approx. 4000 (large area) | |||

| London | air force | August 24, 1940 | predominantly urban area | approx. 30,000 | |||

| Manchester | air force | August 1940 | 22.-24. December 1940 | Port, industry, urban area | |||

| Norwich | air force | 27.-30. April 1942 | historic downtown | ► | |||

| Nottingham | air force | 8/9 May 1941 | Industry | ||||

| Plymouth | air force | July 6, 1940 | Docks | 1172 | |||

| Sheffield | air force | 12./15. December 1940 | Defense industry | 660 | |||

| Southampton | air force | November 30th / 1st December 1940 | port | 470 | |||

| Swansea | air force | February 1941 | Port, industry | ||||

| York | air force | April 29, 1942 | historic downtown | ► |

Italy

Japan

| city | attacker | First attack | Heaviest attack | Objectives, degree of destruction | Bomb load (t) | dead | items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akashi | USAAF | July 6, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed to 57% |

885 | 355 | ||

| Akita | USAAF | August 14, 1945 | Ind., Civil. | 970 | 250 | ||

| Aomori | USAAF | July 28, 1945 | Ind., Civil. 88% of the city destroyed |

496 | 1,016 | ||

| Chiba | USAAF | June 10, 1945 | July 6, 1945 | Ind., Civil., Mili. City destroyed to 44% |

932 | 1,530 | |

| Chōshi | USAAF | July 19, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed to 34% |

570 | |||

| Fukui | USAAF | July 19, 1945 | Infra., Civil. City destroyed to 86% |

865 | |||

| Fukuyama | USAAF | August 8, 1945 | Infra., Civil. City destroyed to 81% |

504 | |||

| Gifu | USAAF | July 9, 1945 | Infra., Civil. 64% of the city destroyed |

815 | 890 | ||

| Hachiōji | USAAF | July 2, 1945 | August 1, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed by 65% |

1445 | 398 | |

| Hamamatsu | USAAF | February 15, 1945 | June 18, 1945 | Ind., Civil., Mili. City destroyed to 60% |

2,497 | > 3,570 | |

| Himeji | USAAF | July 3, 1945 | Ind., Civil. 63% of the city destroyed |

696 | |||

| Hiratsuka | USAAF | July 16, 1945 | Ind., Mili. City destroyed to 48% |

1,055 | 253 | ||

| Hiroshima | USAAF | August 6, 1945 | Ind., Infra., Mili., Civil. | 4.04 (nuclear) | 90,000 - 166,000 | ► | |

| Hitachi | USAAF | July 19, 1945 | July 19, 1945 | Ind., Infra., Civil. 72% of the city destroyed |

874 | ||

| Ichinomiya | USAAF | July 12, 1945 | Ind., Infra., Civil. City destroyed to 75% |

700 | |||

| Imabari | USAAF | May 7, 1945 | August 5, 1945 | Ind., Civil. 64% of the city destroyed |

530 | 484 | |

| Kagoshima | USAAF | April 8, 1945 | June 17, 1945 | Ind., Infra., Mili., Civil. 63% of the city destroyed |

885 | ||

| Kawasaki | USAAF | April 15, 1942 | July 25, 1945 | Ind., Infra., Civil. City destroyed by 35% |

320 | 1,520 | ► |

| Kobe | USAAF | February 4, 1945 | June 5, 1945 | Ind., Infra., Mili., Civil. City destroyed to 56% |

7,250 | 6,300 | ► |

| Kochi | USAAF | July 3, 1945 | Infra., Civil. City destroyed to 55% |

962 | |||

| Kofu | USAAF | July 6, 1945 | Ind., Civil. 79% of the city destroyed |

880 | 740 | ||

| Kumagaya | USAAF | August 14, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed to 45% |

538 | |||

| Cure | USAAF | May 5, 1945 | June 22, 1945 | Ind., Infra., Mili., Civil. City destroyed to 42% |

721 | ||

| Kuwana | USAAF | July 16, 1945 | July 24, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed to 77% |

643 | ||

| Maebashi | USAAF | August 5, 1945 | Infra., Civil. 64% of the city destroyed |

657 | |||

| Matsuyama | USAAF | July 26, 1945 | Infra., Civil. City destroyed to 73% |

813 | |||

| Mito | USAAF | August 2, 1945 | Infra., Civil. 69% of the city destroyed |

1039 | 242 | ||

| Moji | USAAF | June 28, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed to 27% |

583 | |||

| Nagaoka | USAAF | August 1, 1945 | Ind., Infra., Civil. 66% of the city destroyed |

566 | > 1,500 | ||

| Nagasaki | USAAF | August 9, 1945 | Ind., Infra., Mili., Civil. | 4.67 (nuclear) | 61,000-80,000 | ► | |

| Nagoya | USAAF | December 13, 1944 | May 16, 1945 | Ind., Infra., Mili., Civil. City destroyed to 40% |

12,750 | 8,150 | ► |

| Nara | USAAF | June 9, 1945 | Infra., Civil. 69% of the city destroyed |

||||

| Nishinomiya | USAAF | August 5, 1945 | Ind., Civil., City destroyed to 30% |

1839 | |||

| Nobeoka | USAAF | June 28, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed by 36% |

752 | |||

| Numazu | USAAF | November 27, 1944 | July 17, 1945 | Infra., Mili. City destroyed to 42% |

943 | 322 | |

| Ōgaki | USAAF | July 28, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed to 40% |

598 | |||

| Okayama | USAAF | June 29, 1945 | Ind., Civil. 69% of the city destroyed |

890 | > 1,200 | ||

| Okazaki | USAAF | July 19, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed by 68% |

771 | 216 | ||

| Ōmuta | USAAF | June 1945 | July 26, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed by 36% |

1,574 | ||

| Osaka | USAAF | March 13, 1945 | August 14, 1945 | Ind., Infra., Mili., Civil. City destroyed by 35% |

9,317 | 12,620 | ► |

| Sakai | USAAF | July 9, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed to 44% |

790 | |||

| Sasebo | USAAF | June 28, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed to 48% |

977 | |||

| Sendai | USAAF | July 9, 1945 | July 19, 1945 | Ind., Infra., Civil. City destroyed by 22% |

975 | 2,755 | |

| Shimonoseki | USAAF | July 1, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed by 36% |

724 | |||

| Shimizu | USAAF | July 6, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed by 50% |

934 | |||

| Shizuoka | USAAF | March 1945 | June 19, 1945 | Ind., Infra., Civil. 66% of the city destroyed |

788 | 1.952 | |

| Takamatsu | USAAF | July 3, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed by 78% |

776 | |||

| Tokyo | USAAF | November 24, 1944 | March 9, 1945 | Ind., Infra., Mili., Civil. City destroyed by 51% |

20,760 | > 100,000 | ► |

| Tokushima | USAAF | December 22, 1944 | July 3, 1945 | Ind., Infra., Civil. City destroyed to 85% |

756 | 1,000 | |

| Tokuyama | USAAF | July 26, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed to 37% |

682 | |||

| Toyama | USAAF | August 1, 1945 | August 1, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed to 99% |

1329 | 2.149 | |

| Toyohashi | USAAF | January 1945 | June 20, 1945 | Ind., Infra., Civil. 62% of the city destroyed |

859 | 650 | |

| Toyokawa | USAAF | November 1, 1944 | August 7, 1945 | Ind., Infra., Mili., Civil. 62% of the city destroyed |

738 | 2,677 | |

| Tsu | USAAF | June 1945 | July 28, 1945 | Infra., Civil. 69% of the city destroyed |

1,187 | 1,239 | |

| Tsuruga | USAAF | July 12, 1945 | Infra., Civil. City destroyed by 65% |

616 | |||

| Ube | USAAF | July 2, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed to 23% |

167 | 230 | ||

| Ujiyamada | USAAF | July 28, 1945 | Ind., Civil. 39% of the city destroyed |

673 | |||

| Utsunomiya | USAAF | June 15, 1944 | July 12, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed to 34% |

767 | ||

| Uwajima | USAAF | July 28, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed to 52% |

186 | |||

| Wakayama | USAAF | July 9, 1945 | Infra., Civil. City destroyed by 50% |

726 | |||

| Yawata | USAAF | June 15, 1944 | August 8, 1945 | Ind., Civil. City destroyed by 21% |

1,181 | ||

| Yokkaichi | USAAF | June 18, 1945 | Ind., Infra., Mili., Civil. City destroyed to 57% |

515 | 736 | ||

| Yokohama | USAAF | April 15, 1942 | April 15, 1945 | Ind., Infra., Mili., Civil. 79% of the city destroyed |

1,457 | 4,830 | ► |

Yugoslavia

| city | attacker | First attack | Heaviest attack | aims | Bomb load (t) | dead | items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgrade | air force | April 6, 1941 | Ind., Infra., Mili., Civil. | 830 | 2,271 | ► |

Netherlands

| city | attacker | First attack | Heaviest attack | aims | Bomb load (t) | dead | items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arnhem | USAAF | February 22, 1944 | Civil. | ► , ► (PDF; 2.4 MB) | |||

| The hague | RAF | 3rd / 4th March 1945 | Civil. | 86 | about 500 | ► | |

| The hero | |||||||

| Eindhoven | USAAF | December 6, 1942 | September 18, 1944 | Civil. | [2] | ||

| Enschede | USAAF | January 22, 1942 | October 10, 1943 | Civil. | 151 | ||

| Goor | USAAF | March 24, 1945 | March 24, 1945 | Civil. | 82 | ||

| Hengelo | USAAF | October 6, 1944 | Civil. | 100 | |||

| Middelburg | air force | May 17, 1940 | Civil. | [3] | |||

| Montfort | RAF | January 21, 1945 | January 21, 1945 | Civil. | 183 | ||

| Nijmegen | USAAF | February 22, 1944 | February 22, 1944 | Civil. | 40 | about 800 | ► , ► (PDF; 2.4 MB) |

| Rotterdam | air force | May 14, 1940 | May 14, 1940 | Civil. | 97 | 800-900 | ► |

| Venlo | RAF | November 3, 1944 | Civil. | 40 | |||

| Vlissingen | air force | May 10, 1940 | Civil. | [4] | |||

| Zutphen | RAF | October 14, 1944 | Civil. | 73 |

Poland

| city | attacker | First attack | Heaviest attack | aims | Bomb load (t) | dead | items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frampol | air force | September 13, 1939 | September 13, 1939 | ||||

| Warsaw | air force | September 1, 1939 | September 25, 1939 | 572 | |||

| Wieluń | air force | September 1, 1939 | September 1, 1939 | Mili. | 1200 | ► |

Romania

Air strikes on cities in Romania, ordered by population size:

Switzerland

Although Switzerland was neutral during World War II, there were bombs on Swiss territory , which the Allies officially justified with navigation errors. Schaffhausen (old town, train station and industry near Neuhausen; 40 dead) and Stein am Rhein on April 22, 1945 (nine dead) were hit particularly hard . It is not entirely clear whether all of these bombings were mistaken or whether they were at least partially intended to be a warning to Switzerland because of its economic relations with the German Reich and the associated cooperation with the Nazi government .

Soviet Union

The most heavily bombed Soviet cities include Leningrad (during the Leningrad blockade ) and Stalingrad (during the Battle of Stalingrad ). Air strikes on Moscow essentially took place only in the first phase of the war. Initially, the goal was mostly to prepare for the capture by the ground troops, later to paralyze industry. Other cities bombed include Minsk , Odessa , Kiev , Sevastopol and Murmansk . Important goals were electricity, water and power plants as well as industrial companies. The Uralbomber projected before the war to attack distant armaments factories was not used. The German plan Aktion Russland of 1943 to wage a strategic air war against the Soviet armaments industry failed because of the advance of the Red Army.

Documentaries

- The firestorm. ZDF 2006. Shown in Phoenix on February 13, 2014, 8:15 pm - 9:45 pm.

Museum reception

The Allied air raids on targets in Austria are extensively documented in the Vienna Army History Museum . Among other things, the figurine of a US fighter bomber pilot, parts of a shot down B-17 as well as phosphor and other aerial bombs are exhibited.

See also

- History of radar

- Destroyed in World War II (Category)

- Bomb certificate

- List of Australian fighter pilots in World War II

literature

- Ansbert Baumann: Evacuation of Knowledge. The relocation of research institutes relevant to the air war to Upper Swabia 1943–1945. In: Journal of Württemberg State History. 67th volume (2008), pp. 461–496.

- Horst Boog (ed.): Air warfare in World War II: an international comparison. Herford 1993.

- Ralf Blank : Battle of the Ruhr. The Ruhr area in the war year 1943. Klartext, Essen 2013, ISBN 978-3-8375-0078-3 .

- Ralf Blank: Everyday life in the war and aerial warfare on the “home front”. In: The German Reich and the Second World War. Volume 9/1: The German War Society 1939–1945. Half Volume 1: Politicization, Annihilation, Survival. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-421-06236-6 , pp. 357-461.

- Olaf Groehler : History of the Air War 1910 to 1980. Berlin 1981.

- Christoph Kucklick : Firestorm. The bombing war against Germany. Ellert & Richter, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-8319-0134-1 .

- Rolf-Dieter Müller : The bombing war 1939-1945. Links, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-86153-317-0 .

- Richard Overy : The Bomb War. Europe 1939–1945. Translated from the English by Hainer Kober, Rowohlt, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-87134-782-5 .

- WG Sebald : Air War and Literature: With an essay on Alfred Andersch . Fischer Taschenbuch, 1999, ISBN 978-3-596-14863-9 (Carl Hanser Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-446-23432-1 ).

- Kultur- und Stadthistorisches Museum Duisburg (Ed.): Bombs on Duisburg. The aerial warfare and the city 1940-1960. Duisburg 2004, ISBN 3-87463-369-1 .

- Dietmar Süß: Death from the air. War society and aerial warfare in Germany and England. Siedler, Munich 2011.

- Susanne Vees-Gulani: Trauma and Guilt: Literature of Wartime Bombing in Germany. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2003, ISBN 978-3-11-017808-1 .

- Regulation L.Dv. 16 - Air Warfare - 1935

Web links

- Bombs on Chemnitz - the facts

- Royal Air Force Bomber Command 60th Anniversary - Campaign Diary February 1945

- Timeline and Chronicle - 1945 historicum.net

- The air raids on cities in the Living Museum Online of the German Historical Museum

Remarks

- ↑ 28 Fokker G.1, 31 Fokker D.XXI, 7 Fokker D.XVII, 10 twin-engine Fokker TVs, 15 Fokker CX, 35 Fokker CV, 12 Douglas DB-8, 17 Koolhoven FK-51.

-

^ For example, the propaganda film about the bombing of Hamburg. Over 40,000 people died in this attack.

- ↑ This was a barracks.

- ↑ The first attack on August 24, 1940 was originally aimed at an industrial area 60 km east of London ("Thames Gateway"). However, one plane went off course and dropped bombs over several parts of London. The first planned attack took place on September 7, 1940.

- ↑ The attack on Wieluń was a tactical attack on the 28th Polish division and a cavalry brigade, which were discovered in Wielun on the eve of the attack by a scout. Because of the fog, the attack missed its real target. Rolf-Dieter Müller: The bombing war 1939-1945. Berlin 2004, p. 53 f. Horst Boog (ed.): Air warfare in World War II: an international comparison. Herford 1993, ISBN 3-8132-0340-9 . There was also a sugar factory on the outskirts of town.

Individual evidence

- ^ Rolf-Dieter Müller: The bombing war 1939-1945. Berlin 2004, pp. 24–28.

- ^ Olaf Groehler: History of the Air War 1910 to 1980. Berlin 1981, p. 118.

- ^ Sven Felix Kellerhoff : The war crime of Wielun. In: The world . September 2, 2009.

- ↑ 110 Avions Fairey Fox , 19 Renard R 31, 14 Fairey Battle , 23 Fiat CR.42 , 15 Gloster Gladiator and 11 Hawker Hurricane france1940.free.fr

- ↑ SGLO crash database. Studiegroep Luchtoorlog 1939–1945, accessed on June 16, 2020 (English).

- ↑ studiegroepluchtoorlog.nl

- ^ David Divine: The Nine Days of Dunkirk. White Lion, 1976, ISBN 0-7274-0195-5 .

- ^ Richard Collier: Dunkirk. Heyne Verlag, 1982, ISBN 3-453-01164-3 , p. 331.

- ↑ August 1942 USAAF Overseas Accident Reports. Retrieved June 16, 2020 (English).

-

^ Matthew White: Twentieth Century Atlas - Death Tolls: United Kingdom. lists the following totals and sources:

- 60,000, (bombing): John Keegan : The Second World War (1989);

- 60,000: Boris Urlanis_ Wars and Population (1971)

- 60,595: Harper Collins Atlas of the Second World War

- 60,600: John Ellis: World War II: a statistical survey (Facts on File, 1993) "killed and missing"

- 92,673, (incl. 30,248 merchant mariners and 60,595 killed by bombing): Encyclopaedia Britannica. 15th edition, 1992 printing. "Killed, died of wounds, or in prison ... exclud [ing] those who died of natural causes or were suicides."

- 92,673: Norman Davies: Europe A History (1998) same as Britannica's war dead in most cases

- 92,673: Michael Clodfelter : Warfare and Armed Conflict: A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1618-1991 ;

- 100,000: William Eckhardt, a 3-page table of his war statistics printed in World Military and Social Expenditures 1987-88 (12th ed., 1987) by Ruth Leger Sivard. "Deaths", including "massacres, political violence, and famines associated with the conflicts."

-

↑ German Deaths by aerial bombardment (It is not clear if these totals includes Austrians, of whom about 24,000 were killed (see Austrian Press & Information Service, Washington, DC ( Memento from April 20, 2006 in the Internet Archive )) and other territories in the Third Reich but not in modern Germany)

- 600,000 about 80,000 were children in Hamburg, July 1943. Der Spiegel TV 2003

- Matthew White: Twentieth Century Atlas - Death Tolls. lists the following totals and sources:

- more than 305,000: (1945 Strategic Bombing Survey );

- 400,000: Hammond Atlas of the 20th Century (1996)

- 410,000: RJ Rummel , 100% democidal ;

- 499,750: Michael Clodfelter : Warfare and Armed Conflict: A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1618-1991 ;

- 593,000: John Keegan : The Second World War (1989);

- 593,000: JAS Grenville citing "official Germany" in A History of the World in the Twentieth Century (1994)

- 600,000: Paul Johnson : Modern Times (1983)

-

↑ Matthew White: Twentieth Century Atlas - Death Tolls: Allies bombing of Japan. lists the following totals and sources

- 330,000: 1945 US Strategic Bombing Survey;

- 363,000: (not including post-war radiation sickness); John Keegan The Second World War (1989);

- 374,000: RJ Rummel , including 337,000 democidal ;

- 435,000: Paul Johnson : Modern Times (1983)

- 500,000: (Harper Collins Atlas of the Second World War)

- ↑ USAF: The Bombing of Dresden. ( Memento from September 24, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) Dresden was protected by antiaircraft defenses, antiaircraft guns and searchlights, in anticipation of Allied air raids against the city. The Dresden air defenses were under the Combined Dresden (Corps Area IV) and Berlin (Corps Area III) Luftwaffe Administration Commands.

- ↑ Gerd R. Ueberschär: Dresden 1945 - symbol for aerial war crimes. In: Wolfram Wette, Gerd R. Ueberschär (Ed.): War crimes in the 20th century. Darmstadt 2001, pp. 382-396, here p. 392.

- ↑ Thomas Widera: Review of Reinhard Oliver, Matthias Neutzner, Wolfgang Hesse (eds.): The red glow. Dresden and the bombing war. Dresden 2005. In: H-Soz-u-Kult. June 14, 2005: "The retrospective judgment is in danger of insufficiently considering the complexity of historical processes."

- ^ Götz Bergander: Dresden in the air war - prehistory, destruction, consequences. Special edition, 2nd extended edition. Würzburg 1998, ISBN 3-88189-239-7 .

- ↑ Götz Bergander: From rumor to legend. The aerial warfare over Germany in the mirror of facts, experienced history, memories, memory distortion. In: Thomas Stamm-Kuhlmann u. a. (Ed.): Historical images. Festschrift for Michael Salewski on the occasion of his 65th birthday, Stuttgart 2003.

- ↑ Helmut Schnatz: Low-flying aircraft over Dresden? Legends and Reality. With a foreword by Götz Bergander. Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2000, ISBN 3-412-13699-9 .

- ↑ Frederick Taylor: Dresden, Tuesday, February 13, 1945. Military logic or sheer terror? Bertelsmann, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-570-00625-5 .

- ↑ Matthias Neutzner (ed.): Martha Henry Eight - Dresden 1944/45. 4th expanded edition. Dresden 2003 (first edition 1995)

- ↑ Matthias Neutzner, Wolfgang Hesse (ed.): The red lights. Dresden and the bombing war. edition Sächsische Zeitung, Dresden 2005, ISBN 3-938325-05-4 .

- ↑ Matthias Neutzner: The story of 13 February. In: Myth Dresden. Fascination and transfiguration of a city. Dresdner Hefte, Vol. 84, ISBN 3-910055-79-6 .

- ^ Werner Wolf: Air raids on German industry 1942–1945. Universitas 1985. ISBN 3-8004-1062-1 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Trees , Charles Whiting, Thomas Omansen: Three years after zero. History of the British Zone of Occupation 1945–1948. Gondrom 1979, ISBN 978-3-8112-0644-1 , p. 49.

- ↑ Federal Ministry for Expellees, Refugees and War Victims (Neuhoff / Schodrok): Documents of German war damage: evacuees - war victims - currency victims. The historical and legal development. Volume II / 2. The situation of the German people and the general legal problems of the victims of the air war from 1945–1948. Bonn 1960, p. 48.

- ↑ Historical Center Hagen: May 13, 1940 Duisburg suffers from the first major bombing of the war ( Memento from April 15, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ 60 years of the end of the war ( memento from June 4, 2008 in the Internet Archive ), kriegsende.ard.de ( ARD joint production by BR, NDR, RBB, SR, SWR and WDR).

- ↑ See Hansjakob Stehle: "The spies from the rectory" in: The time of January 5, 1996.

- ↑ Peter Broucek: The Austrian Identity in the Resistance 1938-1945. In: Military resistance: studies on the Austrian state sentiment and Nazi defense. Böhlau Verlag , 2008, p. 163 , accessed on August 3, 2017 .

- ↑ Andrea Hurton, Hans Schafranek: In the network of traitors. In: derStandard.at . June 4, 2010. Retrieved August 3, 2017 .

- ↑ See Peter Pirker “Suberversion deutscher Herrschaft. The British secret service SOE and Austria ”(2012), p. 252 ff.

- ↑ Explained by Franz Graf-Stuhlhofer : Sustainable peace policy in acute cases. War shortening as a result of the link between the struggle from outside and inside , in: Society & Politics. Journal for social and economic engagement, 2019, no. 3, pp. 135-137.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am Jörg Friedrich: Der Brand. Germany in the bombing war 1940–1945 . 2nd Edition. Propylaea, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-549-07165-5 .

- ↑ https://www.ln-online.de/Lokales/Stormarn/Als-Bomben-auf-Bad-Oldesloe-fielen-Ein-Zeitzeuge-beriziert

- ^ The air raid on Böblingen from 7/8 October 1943. Retrieved August 6, 2019 .

- ^ Eckart Grote: Target Brunswick 1943–1945. Air raid target Braunschweig - documents of destruction. Braunschweig 1994, p. 11.

- ↑ Rudolf Prescher: The red rooster over Braunschweig. Air protection measures and aerial warfare events in the city of Braunschweig 1927 to 1945. Braunschweig 1955, p. 88.

- ↑ a b c Braunschweiger Zeitung (ed.): The bomb night. The air war 60 years ago. Braunschweig 2004, p. 8.

- ↑ Braunschweiger Zeitung (ed.): The bomb night. The air war 60 years ago. Braunschweig 2004, p. 43.

- ↑ Timeline of the 20th century. Retrieved May 4, 2019 .

- ↑ Helmut Wolf: Erfurt in the air war 1939-1945. Jena 2005, ISBN 3-931743-89-6 .

- ↑ Bombs on Freital ( Memento from December 21, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Raimund Hug-Biegelmann: Friedrichshafen in the strategic aerial warfare 1943-1945. In: Writings of the Association for the History of Lake Constance and its Surroundings. 113, 1995, pp. 47-70.

- ↑ Thomas Heiler : Basics of the Fulda industrial history in the 19th and 20th centuries in Gregor Stasch (ed.), Thomas Heiler: Maschinenbau in Fulda - Klein & Stiefel (1905–1979) (book accompanying the exhibition in the Vonderau Museum from January 20th - April 2, 2006), Imhof Verlag, Petersberg, ISBN 3-86568-067-4 , p. 6.

- ↑ Manfred Mümmler: Fürth 1933-1945. Emskirchen 1995, p. 175 ff.

- ^ A b Walter Brunner: Bombs on Graz: The Documentation Weissmann. Leykam Verlag, Graz 1989, ISBN 3-7011-7201-3 .

- ↑ Jörg Monzheimer: Night of the bombs - Bürstädter Zeitung. August 25, 2017. Retrieved May 2, 2019 .

- ^ A b Hans Brunswig: Firestorm over Hamburg. Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-87943-570-7 , pp. 213, 243.

- ^ Exhibition of the Lower Saxony Volksbund: "Lower Saxony at War" - youth serves the leader. (PDF; 533 kB)

- ↑ Klaus Mlynek, Waldemar R. Röhrbein (ed.): Hanover Chronicle: From the beginnings to the present. Numbers, data, facts. Schlütersche, Hanover 1991.

- ^ Only March 22, 1945 according to Menno Aden: Hildesheim is alive . Gerstenberg, Hildesheim 1994, ISBN 3-8067-8551-1 .

-

↑ Total number, including 824 victims on March 22, 1945 according to Manfred Overesch: Bosch in Hildesheim 1937–1945 . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-525-36754-4 , p. 290 . ≥1006 victims on March 22, 1945 according to Menno Aden: Hildesheim is alive . Hildesheim 1994.

- ^ Total number according to Friedrich: The fire . 2002, p. 215 .

- ↑ Eduard Hauptlorenz: The Kaiserslautern area in aerial warfare: Air defense - Air protection - Air raids, 1939 to 1945. Series of publications by the Kaiserslautern City Archives, Vol. 8, Kaiserslautern 2004, ISBN 3-936036-10-1 .

- ↑ Helmut Schnatz: Koblenz in the bombing war. historicum.net

- ↑ 1944–1945 bombs on Oranienburg. (PDF) In: Oranienburg-erleben.de. Retrieved January 2, 2019 .

- ^ Regionalgeschichte.net , accessed on October 22, 2015.

- ↑ H.-W. Bohl: Bombs on Rostock. Konrad Reich Verlag, ISBN 3-86167-071-2 .

- ↑ http://kriegsende.ard.de/pages_std_lib/0,3275,OID1100854,00.html ( Memento from January 31, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ The air raids on the city of Salzburg . After simultaneous records and found Communications from the Municipal Statistical Office. In: Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Salzburger Landeskunde , No. 86/87, year 1946/47, pp. 118–121. Digitized .

- ↑ Zweibrücken 600 years of the city. Published by the Zweibrücken Historical Association on behalf of the Zweibrücken city administration, Zweibrücken 1952, p. 347.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : German history of society. Vol. 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states 1914–1949. CH Beck, Munich 2003, p. 943.

- ↑ Subject. Shot down and lost. SWR, February 19, 2014, 8:15 pm - 9:00 pm.

- ↑ The now little known "trolley" missions. Some recordings at the Washington National Archives.

- ↑ Trolley Missions Overview. ( Memento from June 28, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Engl. Many recordings. On the site b24.net/ of the 392nd Bomb Group (392nd Bomb Group, there is also talk of sightseeing trips.)

- ^ Royal Air Force Bomber Command 60th Anniversary Campaign Diary September 1944 ( Memento from March 31, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ wlb-stuttgart.de

- ↑ a b raf.mod.uk ( Memento from March 4, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Jack McKillop: USAAF Chronology. Retrieved January 18, 2016 .

- ^ The Zinn reader: writings on disobedience and democracy. Howard Zinn p. 267 ff. Books.google.com

- ↑ thepinklady.fr ( Memento of July 24, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Cardiff's 'worst night' of Blitz remembered 70 years on on bbc.co.uk from January 2, 2011, accessed June 7, 2011.

- ↑ a b c d e United States Strategic Bombing Survey: The Effecits of Incendiary Bomb Attack on Japan - A report on eight Cities. United States Strategic Bombing Survey, 1947.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q United States Strategic Bombing Survey: The Pacific War. United States Strategic Bombing Survey, 1947.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r The Twentieth Air Force Association. Retrieved January 18, 2016 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Martin Caidin: A Torch to the Enemy: The Fire Raid on Tokyo. Bantam War Books, 1960. ISBN 0-553-29926-3 .

- ↑ 岐阜 市 空襲 の あ ら ま し ( Memento from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Accessed: March 3, 2015.

- ↑ a b c d e United States Strategic Bombing Survey: The effects of air attack on Japanese urban economy. Summary report 1947, p. 5 f.

- ↑ Frequently Asked Questions # 1 . Radiation Effects Research Foundation . Archived from the original on September 19, 2007. Retrieved September 18, 2007.

- ↑ Chapter II: The Effects of the Atomic Bombings . In: United States Strategic Bombing Survey . Originally by USGPO ; stored on ibiblio .org. 1946. Retrieved September 18, 2007.

- ↑ Nagaoka Air Raid August 1.1945. Accessed February 27, 2015.

- ↑ Takeshi Ohkita: Acute Medical Effects in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. P. 85.

- ↑ nuclear A-Z .

- ↑ Stern (magazine): Nagasaki remembers its victims .

- ^ Overview of the Nagasaki University School of Medicine ( Memento of March 29, 2002 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Tokushima Air Raids Digital Archive. Accessed March 3, 2015.

- ^ Incendiary Bombing of Toyama in WW2 Accessed March 2, 2015.

- ↑ a b c d e http://nl.milpedia.org/wiki/Geallieerde_bombardementen_op_Nederland_tijdens_de_Tweede_Wereldoorlog ( Memento from December 29, 2017 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Army History Museum / Military History Institute (ed.): The Army History Museum in the Vienna Arsenal. Verlag Militaria , Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-902551-69-6 , p. 143.