Bomb raid on Braunschweig on October 15, 1944

The bombing raid on Braunschweig on October 15, 1944 by the 5th bomber group of the Royal Air Force (RAF) marks the climax of the destruction of the city of Braunschweig during the Second World War . The air attack created a firestorm that raged for two and a half days, destroyed over 90% of the medieval inner city and has permanently changed the appearance of the city up to the present day. The area bombing of civil targets (inner city, residential areas and others) by the RAF took place on the basis of the " Area Bombing Directive " issued by the British Air Ministry on February 14, 1942 .

Target Braunschweig

The first air raid on Braunschweig took place on August 17, 1940 by the Royal Air Force; seven people were killed. From that day on, the air raids became more numerous, more precise and more devastating in their effects. Since January 27, 1943, the bombers of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) attacked German cities during the day. From February 1944 (“ Big Week ”) Braunschweig was a scheduled target for American and British bomber squadrons, with the RAF flying the night raids and the USAAF the day raids. This division corresponded to the " Combined Bomber Offensive " ( CBO) established at the 1943 Casablanca Conference , a joint approach by the bomber forces of Great Britain and the USA .

Research and armaments sites in and around Braunschweig

In the 1930s Braunschweig was continuously developed into a center of the German armaments industry . The large factories, some of which were located in the middle of the city, attracted thousands of workers for whom new residential areas had to be created. B. the garden city built from mid-1933 as " Dietrich-Klagges-Stadt " and the NS model settlements Lehndorf , Mascherode-Südstadt and Schuntersiedlung.

All in all, Braunschweig - at the beginning of the 20th century mainly a working class and industrial city - was exposed to around 42 air raids by British and American bomber groups during the Second World War. The attacks were mainly aimed at the armaments factories in and around Braunschweig, which in particular manufactured warplanes , tanks , trucks and optical and precision mechanical instruments, the port on the Mittelland Canal , the canning factories , the railway stations and the Reichsbahn repair shop .

Further goals were the four institutes of the Technical University of Braunschweig , founded in the city between 1936 and 1939 : the institutes for aircraft construction , engine theory, aerodynamics as well as for aeronautical measurement technology and flight meteorology . The new aviation training center at Waggum Airport was created from them . Since 1936 the Aviation Research Institute Hermann Göring (LFA) was located in the south near Völkenrode . The Institute for Structural Air Protection was also important to the war effort .

Arms factories in and around Braunschweig (selection)

Braunschweig's most important armaments companies were in addition to those in the aircraft industry such as B. the aircraft works Braunschweig GmbH the Luther works , which u. a. Fighter aircraft of the type Bf 110 produced, the Niedersächsische Motorenwerke (NIEMO) and the Vorwerk Braunschweig of the Volkswagenwerk , which produced fighter aircraft of the type Ju 88 . In addition, there were smaller companies that mainly performed repair and supply tasks such as Grotrian-Steinweg for aircraft or MIAG , which manufactured tanks and assault guns III .

Büssing was an important war company for the production of trucks, while the Schuberth works primarily manufactured steel helmets . Companies in the mechanical and plant engineering were the Braunschweigische Maschinenbauanstalt (BMA), Sparse & Hammer, Wilke-Werke , Wullbrandt & soul , Lanico, Selwig & Lange , as well as to Siemens & Halske owned railway signal Bauanstalt Max Jüdel & Co. for precision engineering and precision optical instruments such as aiming devices ( reflex sights ) or ( aerial ) cameras were known to the Franke & Heidecke and Voigtländer companies . In addition, there were a large number of companies of different sizes that were active in many areas that were important to the war economy, such as the tin can manufacturer Schmalbach .

In the immediate vicinity of Braunschweig, the Reichswerke Hermann Göring was located in Salzgitter approx. 15 km south and the Volkswagen plant approx. 25 km northeast near Fallersleben .

The city gradually developed into the "City of Aviators" in the 1930s. The Air Force Command 2 had its location on Nußberg , next to the newly built "flyer quarter" (houses for members of the Air Force ). In addition, there was the “Air Force Hospital ” on Salzdahlumer Strasse (later the Municipal Clinic ) and numerous barracks. Airfields were built or expanded in Waggum, Broitzem and Völkenrode. In the course of the war, they were gradually drawn into the systematic destruction, as was the entire city.

Air defense in and around Braunschweig

Anti-aircraft positions

Because of its importance as an industrial and research location Braunschweig was from about the autumn of 1943 by a tightly closed, strong and deeply staggered belt of flak - batteries surrounded, which made the city for the attacking bombers a feared target because each time with heavy losses to was to be expected. The Braunschweig and surrounding area belonged to Luftgaukommando XI (Hamburg), 8th Flak Brigade, Flak Regiment 65.

Braunschweig's air defense had around 100 guns of caliber 8.8 cm or larger, which were divided into batteries, double batteries or large batteries. A "battery" usually comprised six guns (mostly 8.8 cm flak , but also 10.5 cm ), a "double battery " consequently had twelve cannons, and a large battery was a combination of ten individual batteries . There were also countless light flak units for defense against low-level aircraft and direct property protection.

In the city itself and in its immediate vicinity there were the following air defense positions: Single batteries Abtstrasse, Eintracht Stadium , Lamme , Ölper and Mascherode, double batteries in Bevenrode , Broitzem , Lünischteich (near Riddagshausen Abbey ), Ölper and Melverode (plus heavy home flak), Querum (partly with railway flak), Wenden and the large battery Wenden. Then there was the Abtstrasse railway flak, at Groß Gleidingen station and in Lehndorf .

Air bases and air force units

In Waggum, Broitzem and Völkenrode some airfields had existed since 1916. These were taken over by the Luftwaffe in the 1930s and expanded for the war.

The following units were at least temporarily stationed on them:

- I. Jagdgeschwader Group 11

- III. Group of Jagdgeschwader 302 " Wilde Sau "

- 3rd squadron night fighter squadron 5

- I. Group Destroyer Squadron 26 "Horst Wessel"

Preparations for the air raid on October 15, 1944

Purpose of the attack

On October 13, 1944, the Royal Air Force received instructions to carry out " Operation Hurricane ". The purpose of this operation was on the one hand to demonstrate the destructive power of the Allied bomber forces against the German civilian population, but on the other hand also to demonstrate their air superiority . The instruction contained the following passage:

“In order to demonstrate to the enemy in Germany generally the overwhelming superiority of the Allied Air Forces in this theater… the intention is to apply within the shortest practical period the maximum effort of the Royal Air Force Bomber Command and the 8th United States Bomber Command against objectives in the densely populated Ruhr. "

"In order to demonstrate to the enemy in Germany in general the overwhelming superiority of the Allied air forces in this theater of war ... it is intended that both the Royal Air Force Bomber Command and the 8th United States Bomber Command should make a maximum effort against targets in densely populated areas in the shortest possible time To undertake in the Ruhr area. "

Operation Hurricane envisaged Duisburg as the main target for the approx. 1000 heavy bombers of the RAF and Cologne for the approx. 1200 bombers of the USAAF. Another 233 RAF bombers were destined for the city of Braunschweig, which at that time had around 150,000 inhabitants.

As early as March 1944, the Commander in Chief of the British Bomber Command , Air Chief Marshal Arthur Harris ("Bomber Harris"), had a list of the six most important bomber targets in the final phase of the war. In the first place: Schweinfurt , followed by Leipzig and in third place Braunschweig, then Regensburg , Gotha and finally Augsburg . The German rolling bearing industry ( FAG Kugelfischer , VKF / Vereinigte Kugellagerfabriken: Fichtel & Sachs / SKF ) was concentrated in Schweinfurt ; the other cities had important aircraft factories ( Erla , Luther-Werke , Messerschmitt , Gothaer Waggonfabrik ). In Augsburg, Messerschmitt AG and MAN ( submarine diesel engines ) were also targeted. Due to the high priority of Braunschweig, Harris and the commander of the 8th US Air Force ("Mighty Eighth"), Major General James Doolittle , decided on March 28, 1944 to launch an attack on the 29th, but this did not bring the desired success because the second part the operation Double Blow to be canceled due to bad weather had. The planned destruction of the city had to be postponed.

Planning for the October attack on Braunschweig had been completed on August 15, 1944. After Darmstadt was "successfully" destroyed on September 11, 1944 as one of the first German cities with a new attack tactic (special marking technique, fan-shaped approach and staggering of the high explosive and incendiary bombs) (approx. 11,500 deaths), the row was on 15 October 1944 now to Braunschweig.

Braunschweig was not only to be destroyed as an important location for the armaments industry, but above all as a civilian place of residence, and thus made permanently uninhabitable and unusable. The goal, namely the greatest possible destruction, should be achieved through detailed attack planning and execution as well as through the properties of the (combat) means used (see below " Mission order " and " War diary "). The means to achieve the goal was the firestorm, the creation of which was not a product of chance, but had been scientifically founded in meticulous detail work.

On October 13, the chief meteorologist at High Wycombe , headquarters of Bomber Command, shared the weather forecast for the weekend of 14-15 with the RAF. October with: low cloud cover, good visibility all night, moderate winds. Then Harris issued the order to attack on 14 October (inter alia in Braunschweig with the target code.. "SKATE" - dt .: " Ray ") The code name of the goals went to the deputy of Harris back: The avid angler Air Vice-Marshal Robert Saundby provided all of the German cities selected with a Fish code .

RAF No. 5 Bomber Group

The No. 5 Bomber Group (motto: "undaunted", German: fearless ) was founded in 1937 and continuously upgraded and modernized during the war. Air Vice Marshal Arthur Harris himself was in command of the group from 1939 to 1940 before becoming Commander in Chief of Bomber Command . In 1943 the headquarters of the group of 15 squadrons towards the end of the war was moved to Morton Hall, Swinderby. The group was commanded by Air Vice Marshal Ralph Cochrane at the time of the attack on Braunschweig . No. 5 Bomber Group was called in for various special missions, such as the bombing of dams ("Dam-Buster-Raid") and the extensive destruction of cities such as B. Cologne, Dresden or Würzburg.

Some of No. 5 Bomber Group:

- first " thousand bomber attack " on Cologne on May 30, 1942 as part of " Operation Millennium "

- Dam-Buster attack on the Möhne and Eder dams on the night of May 17, 1943 (sole execution)

- Air raid on Heilbronn on December 4, 1944 (sole execution)

- Air raid on Dresden on February 13, 1945 (sole execution of the first attack)

- Air raid on Würzburg on March 16, 1945 (sole execution)

In the course of 1944, RAF Bomber Command had already tried four times in vain to destroy Braunschweig permanently, but had so far failed for various reasons (mainly bad weather, defenses that were too strong, etc.). On Saturday, October 14, 1944, at the headquarters of No. 5 Bomber Group in Morton Hall completed the preparations for the attack, at 1:10 p.m. local time the order was issued to all squadrons involved , followed by a briefing of the crews at 3:30 p.m.

Operation order dated October 14, 1944

Translation of extracts from the handwritten, slightly changed deployment order :

- Use: At least 220 aircraft of the No. 5 Group will attack the target. In addition, 1,000 aircraft of the No. 1, 3, 4 and 6 Groups COD [= code name Duisburg ] at 01:29 and 03:25.

- Objective: Complete the destruction of an enemy industrial center.

- Operation day: night 14./15. October 1944

- Forces: 53rd base - more than 80 aircraft, 55th base - more than 100 aircraft, 49th squadron - more than 18 airplanes, 54th base - 13 aircraft (106th squadron) in addition to lighting and marker units.

- Goal: SKATE [= code for Braunschweig ].

- Attack time: Estimated attack time 2:30 a.m. Time over target, attack time +6 minutes. Aircraft have to be evenly distributed over the target during the time. Aircraft with longer delays have to attack in the first wave.

- Bomb charge and detonator: 51 aircraft: 1 × 2000 HC (= air mine ) plus maximum "J" cluster (= flame jet bomb )

- Remaining: 1 × 1000 MC / GP (= high-explosive bomb with impact fuse ). Plus maximum incendiary bombs, preferably in litter boxes, otherwise in bulk boxes.

- Film recordings: All aircraft are to be equipped with night-time cameras and flashing lights that have to ignite at 60% of the flight altitude. All squadrons with the exception of the 106th have to equip 50% of the aircraft with other footage for details. The 106th carries 100% other films.

- Attack: The target is to be attacked in sections radiating from the marking point with a delayed release of the bomb.

- Target marking: Attack time −10 [minutes]: Blind marking. Green target markings are thrown in the middle of the main target (= Frankfurter Strasse , corner of Luisenstrasse). They are renewed at attack time −5. Red marker bombs are dropped over the target at attack time −9, −7 and −5.

- Bombing instructions: When the target markings are red, crews must aim in such a way that the center bomb in their row hits the center of the target.

Course of the air attack

Approach to the destination

No. 5 RAF bomber group took off as planned at around 11 p.m. local time on the evening of October 14th to fly to the “SKATE” target. At the same time, another 1,000 RAF bombers from other groups started to bomb Duisburg. The association destined for Braunschweig took a course leading to it far south of the later destination in order to bypass the anti-aircraft lock belt of the heavily secured Ruhr area . At Paderborn he turned north, crossed Hanover and finally reached Braunschweig. It consisted of 233 heavy, four-engined bombers of the type Avro Lancaster I and III (each with a bomb load of about six tons ); The Lancasters were accompanied by seven De Havilland Mosquitos .

At 1:20 a.m. in Braunschweig the announcement was heard on the radio that “strong enemy bomber formations were approaching Hanover”, which is only 60 km west of Braunschweig. In Braunschweig itself, Kassel was initially suspected as the actual target, but because of its proximity to Hanover, a precautionary “ pre-alarm ” was triggered. 25 minutes later the announcement read: “The head of the reported enemy bomber formation has flown over the city of Hanover and is now approaching Braunschweig.” Thereupon a “full alarm” was triggered in the city. Shortly afterwards the city center was already overflown by the “markers” and the first bombs fell just a few minutes later.

Elimination of German air defense through deception

At about the same time, 141 training aircraft flew a mock attack on Heligoland , 20 mosquitos headed for Hamburg , eight Mannheim , 16 Berlin and two Düsseldorf . In addition, 140 other machines were used for other diversionary maneuvers. In addition, large quantities of tin foil strips (code name " Window ") were dropped around 01:40 in order to disrupt the radar systems of the German air defense system. The combination of sham attacks on widely spaced targets, in connection with window drops, ultimately led to defensive measures from the ground and from the air being almost ineffective that night, as the German night fighters e.g. B. had to act scattered over a much too large area, which significantly reduced their effectiveness.

Marking the target

The mosquitos were for one of the No. 5 Bomber Group responsible for specially developed deep marking technology over the target. The bomber group had permanently improved its target marking technique over the war years and now optimized it. When they arrived via Braunschweig, lighting machines threw off numerous illuminants, which the population called Christmas trees because of their characteristic appearance . Their task was to illuminate the target as bright as day for several minutes for the following bomber bunch, then scout machines dropped different colored target markings. The main target point was in the southwest of the city, in the area of Frankfurter Strasse and the corner of Luisenstrasse, where numerous arms factories were located. An additional target point was set above the Braunschweig Cathedral in the event that the main target was caused by smoke development or the like. should no longer be clearly recognizable. The marking above the cathedral was green and intended as a “blind mark” for the bomb radar. These "Christmas trees" released around 60 glowing candles at a height of 1,000 m, which slowly floated to the ground, burning for around 3–7 minutes. Thanks to the clear night (report from the film reconnaissance: “Visibility: excellent” - “Sight: excellent” ), the enemy-free approach and the perfect marking of the target, the attack conditions were optimal from a British point of view.

The downfall of old Braunschweig

The last all-clear on Saturday, October 14th, in Braunschweig had only just died down at midnight when the air raid alarm was triggered again on the 15th at around 1:50 a.m. - the RAF attack had begun.

Although the air raid only lasted about 40 minutes, Sunday, October 15, 1944, went down in the history of the city as the day when old Braunschweig fell.

No. In addition to the special marking technology, 5 Bomber Group had also developed a sophisticated bombing process that was supposed to cause the greatest possible damage - it was called "sector bombing". It consisted of the cathedral as a point target for the master bomber (“leading bomb shooter”) in the foremost machine. The green marking on the cathedral island was used to orient the bombardiers of all following machines, who flew over this marking in a fan shape from different directions, dropping their bombs.

RAF footage of the attack

This air raid on Braunschweig was filmed by a specially equipped Lancaster. Like most of the bomber crowd, the machine flew at an altitude of 4950 m above the target and at a speed of 260 km / h. The recordings were made with three cameras of the type Bell & Howell "Eyemo". The attack time was recorded as 02:33 a.m. (board time). A copy of this film is now in the Braunschweig City Museum .

The film is provided with the following text:

“Bomber Command… made a heavy and concentrated attack on the industrial town of Brunswick, which is one of Germany's biggest centers for the aircraft and engineering industries. As the aircraft with the cameras runs up to the target the fires can be seen spreading rapidly all over the city and by the time the aircraft is over the target the whole city is ablaze and the streets can be seen clearly outlined. "

“The bomber command… carried out a heavy and concentrated attack on the industrial city of Braunschweig, one of the largest centers for aircraft and mechanical engineering in Germany. As the camera aircraft approaches the target, you can see the fire spreading rapidly across the entire city. When the plane is over the destination, the whole city is on fire, you can clearly see the pattern of the streets. "

The firestorm

Approx. 847 tons of bombs were dropped on the city within just under 40 minutes, initially approx. 12,000 high-explosive bombs (including air mines , so-called "apartment block crackers") in several bomb carpets on the half-timbered town in order to supply the intended firestorm with combustible material as well as possible. The pressure waves covered roofs and exposed the interior of the houses, shattered windows and shattered interior fittings, brought walls to collapse, tore up electricity and water pipes and drove fire-fighting and rescue workers and damage observers into cellars and bunkers . After the explosive bombs, about 200,000 phosphorus and incendiary bombs were dropped. Your job was to start a firestorm. As with attacks on other cities (e.g. Hamburg ), the firestorm was not the product of chance, but the result of the meticulous evaluation of the consequences of previous attacks.

Air masses heated up by the fires were torn upwards by the resulting thermals , colder air flowed in from below; so it came to hurricane-like, constantly changing winds, which fanned the fires even further, which in turn increased the winds and the suction created by them . Small pieces of furniture were swept away and people were knocked over. About three and a half hours later, around 6:30 a.m., the conflagration in the city center finally peaked. 150 hectares of historic urban area were on fire. The tallest church spiers in the city, the almost 100 m high St. Andrew's Church , burned visible from afar and spread a shower of sparks over the entire city area. The entire city center was hit by incendiary bombs. Rescue and fire- fighting forces were prevented from quickly reaching the source of the fire .

Braunschweig burned so intensely and brightly that the glow of the fire could still be seen far away. Helpers and fire brigades streamed into the burning city from distances of up to 90 km.

In the 24 hours that Operation Hurricane lasted, the RAF dropped approximately 10,000 tons of bombs, the highest bomb load dropped in a 24-hour period in all of World War II.

Rescue of 23,000 trapped people using the waterway

The numerous sources of fire in the city center grew into a large-scale conflagration. In this area there were six overcrowded large bunkers and two air raid shelters, into which around 23,000 people had fled. There was a risk that the bunker occupants either suffocated from a lack of oxygen if they stayed in the bunkers, or burned to death if they tried to leave the shelters enclosed by the firestorm.

On the initiative of lieutenant of the Braunschweig fire protection police Rudolf Prescher , among others , it was possible to form a waterway around 5:00 a.m. - even before the fire storm had developed its greatest intensity - through which the evacuation of the 23,000 bunker inmates was made possible. To do this, the firefighters first had to work their way up to the bunkers themselves, risking their lives.

The water alley consisted of a long hose that was driven to the trapped under a constant water veil to protect against the heat of the fire. The ranges of the individual nozzles overlapped, creating a closed, artificial “rain zone”.

On Sunday morning around 7:00 a.m., about an hour after the fire had reached its greatest intensity, the fire brigade reached the bunker. All trapped people were still alive and could go to safe areas such as B. the museum park to be evacuated. In an air raid shelter at Schöppenstedter Strasse 31, help came too late for most of them. 95 out of 104 people had suffocated here due to lack of oxygen.

Statistics as of October 15, 1944

Structure of the city center

In 1944 the inner city consisted of approx. 2800 houses, which had been built over the course of centuries and thus in different style periods.

E. Hundertmark made the following list in 1941:

| Architectural style | Percentage ownership % |

| Gothic | 6.7 |

| Early renaissance | 4.2 |

| insecure types | 11.1 |

| Renaissance | 8.7 |

| Baroque | 24.9 |

| Rococo | 11.5 |

| classicism | 10.7 |

| Post-classicism | 2.5 |

| Founding and pre-war period | 19.2 |

| Present [= 1941] | 0.5 |

Destroyed structures (selection)

The densely built-up city center was largely characterized by around 800 half-timbered buildings, some of which went back to the Middle Ages. In addition, the development consisted of stone buildings, which were mostly built in the 17th and 18th centuries. The tight, z. Sometimes winding streets and their dense development with easily inflammable and combustible half-timbered houses, in connection with the tactics of the British to first use high explosive and then incendiary bombs, initially caused the individual fires to spread quickly and ultimately led to a firestorm after they interlocked. which destroyed almost the entire city center in the 2½ days of its raging. In addition to irreplaceable cultural assets and monuments, residential areas and even entire streets, such as B. Bäckerklint , Geiershagen , Meinhardshof , Nickelnkulk , Südklint , Rehnstoben , Taschenstrasse or the Worth desert are irretrievably lost.

In a situation report of January 25, 1945 to Otto Georg Thierack , Reich Minister of Justice, the Attorney General at the Braunschweig Higher Regional Court wrote :

“The face of the old city of Braunschweig has changed completely. [...] The half-timbered houses that had maintained the impression of a medieval town in some streets and alleys, burned down in rows. "

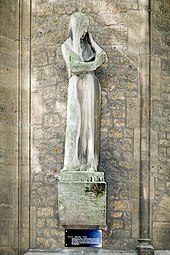

The Brunswick Cathedral, which the Nazis to "national shrine" had turned and the RAF was the target point for the attack that night, had remained however spared by bombs and fire.

In addition to entire streets in the city center, many buildings with significant urban and architectural history were largely or completely destroyed (selection):

| building | built | State after October 15, 1944 |

| Achtermann's house | 1626-1630 | severely damaged |

| Aegidienkirche | 13-15 century | severely damaged |

| Old scales | 1534 | completely destroyed, rebuilt true to the original at the original location from 1990 to 1994 |

| Altstadtmarktbrunnen | 1408 | severely damaged |

| Andreas Church | around 1230 | severely damaged |

| Bierbaum's house | 1523 | completely destroyed |

| Bierbaum villa | 1805 | badly damaged, ruin demolished in 1960 |

| Brunswick Castle | 1833-1841 | badly damaged, demolished in 1960 after heated controversy; The facade was rebuilt at the original location from 2005 |

| Brothers Church | around 1361 | severely damaged |

| Dankwarderode Castle | 1887-1906 | severely damaged |

| Dannenbaum's house | 1517 | completely destroyed |

| Eulenspiegelhaus | 1630 | completely destroyed |

| Gauss Museum | possibly 16th century | completely destroyed |

| Gewandhaus | before 1268 | severely damaged |

| Hagenmarkt pharmacy | 1677 | completely destroyed |

| House Salve Hospes | 1805 | severely damaged |

| Katharinen Church | around 1200 | severely damaged |

| Cross Monastery | around 1230 | completely destroyed |

| Libry | 1412-1422 | severely damaged |

| Magni Church | around 1031 | severely damaged |

| Martineum | 1415 | completely destroyed |

| Martini Church | around 1195 | severely damaged |

| Mummehaus | around 1588 | completely destroyed |

| Packhof | 14./15. Century | completely destroyed |

| Nicolai Church | 1710-1712 | completely destroyed |

| Pauli Church | 1901-1906 | severely damaged |

| Petri Church | before 1195 | severely damaged |

| Stechinelli house | 1690 | severely damaged |

| State Theater | 1861 | severely damaged |

Less than nine hours after the end of the bombing, a British long-range reconnaissance aircraft flew over the city at around 11:40 a.m. to document the damage. As a result of the many fires and the associated heavy smoke development, only a few objects could be seen. An eyewitness said: “It did not get light that day. A huge mushroom cloud darkened the sun. "

On the evening of October 17th, the last major fires were extinguished, and the extinguishing of smaller fires dragged on for three days until October 20th. 80,000 inhabitants, that was 53.3% of the total population of Braunschweig, had become homeless as a result of this attack .

The destruction was so great that the population and experts were still convinced years after the end of the war that it was one of the “ thousand-bomber attacks ” on October 15, 1944, such as the one on Cologne on 30/31. May 1942 , had acted. There was no other way of explaining the extent. It was only after the British military archives were opened that it turned out that there were “only” 233 bombers.

The victims

The exact number of victims in the October 15 attack is unknown. Contemporary numbers vary between 484 and 640 deaths. 101 people were missing, the number of injuries amounted to 1258. However, historians today assume that more than 1000 people were killed as a result of this attack.

These comparatively low losses were due to various factors: Braunschweig was on the direct flight route, in the " approach lane ", to Magdeburg and Berlin and in the immediate vicinity of the major military sites in Salzgitter ( Hermann Göring works ) and Fallersleben ( Volkswagen works ). The Braunschweig population was “trained” by the numerous alarms (2,040 warnings and 620 air raid alarms between 1939 and 1945) to get into the bunkers quickly.

Until mid-1943, the city had largely been spared major bomb attacks and the corresponding destruction. As the war progressed it was only a question of time when such an attack would come, Braunschweig was soon nicknamed "Waiting City in Zittergau". This was a corruption of the term " Gau " used by the National Socialists and the numerous " honorary titles " for German cities and a play on words with the contemporary term “ Warthegau ”. Another reason for the comparatively low number of bomb victims was the number of modern air raid shelters in the city center. In addition, the evacuation of residents must be taken into account. The number of civilians cared for, calculated on the basis of the distribution of the food cards, fell from 201,181 to 152,686 between August 1943 and August 1944 - and was then 138,048 at the beginning of December 1944.

The RAF had lost a Lancaster to anti-aircraft fire via Braunschweig . A second aircraft was so badly damaged by fire that the pilot ordered the crew to jump, which three crew members did. They became prisoners of war. The pilot managed to return to the base with his machine.

Bunker in Braunschweig

Compared to other major German cities, Braunschweig had a large number of the most modern large bunkers . At the "Institute for Building Materials, Solid Construction and Fire Protection" at the Technical University of Braunschweig , the " Braunschweiger Reinforcement " was developed, which, due to its special resistance, became a kind of safety standard for the construction of air raid shelters throughout the German Reich. Despite the large number, the bunkers were overcrowded as the war continued.

| Construction year | place | Places | comment | |

| 1 | 1940 | Old Bonehauerstrasse | 813 | still available, on synagogue grounds |

| 2 | 1940/41 | Old scales | 220 | still there |

| 3 | 1941/42 | Bockstwete | 750 | still available, converted |

| 4th | 1941/42 | Borsigstraße / Bebelhof (then Limbeker Hof) | 800 | tore off |

| 5 | ? | Kaiserstrasse | 642 | still there |

| 6th | ? | Kalenwall (then Adolf-Hitler-Wall) ( old train station ) | 428 | still available, converted |

| 7th | 1941/42 | Kralenriede | 500 | still there |

| 8th | 1941/42 | Ludwigstrasse | 236 | still there |

| 9 | 1941/42 | Madamenweg 130 | 1,500 | still available, converted into condominiums in 2013 |

| 10 | from 1942 | Glogaustraße (then Mascheroder Weg) in Melverode | 350 | still there |

| 11 | 1941/42 | Methfesselstrasse | 1,250 | still available, converted |

| 12 | 1941/42 | Münzstrasse (police) | 450 | still there |

| 13 | 1940/41 | Okerstrasse | 944 | still available, converted into residential building |

| 14th | 1944 | Ritterstrasse | 840 | still available, converted into residential building |

| 15th | 1940/41 | Auerstrasse (then Friedrich-Adolf-Kuls-Strasse) in Rühme | 650 | tore off |

| 16 | 1940/41 | bag | 700 | Demolished in late 2007 / early 2008 to make way for a new building |

| 17th | 1940/41 | Salzdahlumer Strasse | 986 | still available, converted |

| 18th | ? | Stollen in the Nussberg | 10,000 | blown up |

| 19th | ? | Tunnel in the Windmühlenberg | 1,000 | eliminated |

Deployed Brunswick and foreign fire brigades

According to estimates, it is assumed that around 4,500 firefighters were on duty, especially on the night of the bombing itself and on the following six days until the last fires were extinguished. These were members of city fire brigades (including from Blankenburg, Celle, Gifhorn, Hanover, Helmstedt, Hildesheim, Peine, Salzgitter, Wernigerode and Wolfenbüttel) as well as volunteer fire brigades and plant fire brigades from various companies in Braunschweig and the surrounding area. It is thanks to your efforts that the city did not burn completely that night.

aftermath

Reporting in the local Nazi press

On the night of the attack, the National Socialists used the opportunity to instrumentalize the victims for their " total war ", because the next day, Monday, October 16 - the city was still burning - the local " Braunschweiger Tageszeitung " appeared Nazi propaganda organ with the headline: "The devilish grimace of the enemy" and pithy slogans from Gauleiter of South Hanover-Braunschweig Hartmann Lauterbacher to "the Braunschweiger" .

On October 19, the number of "fallen soldiers" on October 15 was given as 405, and on the 20th a full-page obituary with 344 names appeared. On 22, a week after the devastating attack took place in the "Staatsdom" , so since 1940 the used by the Nazis Identification of the Brunswick Cathedral , and Castle Square (then place the SS ) a Gedenkakt for the victims instead, the then predominantly were buried in a specially designed area in the Braunschweig main cemetery .

That same night, Braunschweig was hit by the next heavy air raid, this time it was USAAF B-17 “ Flying Fortress ” bombers . The last bomb attack on the city took place on the morning of March 31, 1945 by the 392nd US Bomber Group and was mainly aimed at the Ostbahnhof, today's Braunschweig main station .

Wehrmacht report for October 15, 1944

The Wehrmacht report of the OKW mentioned the attack on Braunschweig only in passing: " ... Last night the British threw indiscriminately a large number of explosive and incendiary bombs on residential areas of the cities of Duisburg and Braunschweig. Tilsit , Hamburg and Berlin were the target of further night bomb attacks ... "() Nothing is reported about the extent of the destruction and the number of victims.

Bomber Command Diary: October 15, 1944

The war diary of the RAF Bomber Command contains the following entry on the attack on Braunschweig on October 15, 1944:

RAF Bomber Command Campaign Diary October 1944

14/15 October 1944:

[…] Not only could Bomber Command dispatch more than 2,000 sorties to Duisburg in less than 24 hours, but there was still effort to spare for No 5 Group to attack Brunswick with 233 Lancasters and 7 Mosquitos. The various diversions and fighter support operations laid on by Bomber Command were so successful that only 1 Lancaster was lost from this raid. Bomber Command had attempted to destroy Brunswick 4 times so far in 1944 and No 5 Group finally achieved that aim on this night, using their own marking methods. It was Brunswick's worst raid of the war and the old center was completely destroyed. A local report says 'the whole town, even the smaller districts, was particularly hard hit'. It was estimated by the local officials that 1,000 bombers had carried out the raid.

" The RAF Bomber Command's Diary October 1944

14./15. October 1944:

[…] Bomber Command not only managed to fly more than 2,000 sorties against Duisburg in less than 24 hours, No 5 Group was also able to attack Braunschweig with 233 Lancasters and 7 Mosquitos. The various diversionary maneuvers and the fighter protection provided by Bomber Command were so successful that only a single Lancaster was lost in this attack. Bomber Command had already tried to destroy Braunschweig four times in 1944, and No 5 Group succeeded in doing this that night by using their own target marking technology. It was Braunschweig's heaviest air raid of the entire war and the old city center was completely destroyed. A local report read: 'The entire city, even the smaller districts, has been particularly hard hit.' City officials estimated it was a 1,000 bomber attack. "

It is clear from the text that the RAF Bomber Command realized very soon after the air raid how devastating the consequences were for the city of Braunschweig.

Preparations for the destruction of Dresden

In retrospect, the attack on Braunschweig on October 15 can be seen in connection with attacks such as the one on September 11, 1944 on Darmstadt as preparation of the RAF for the destruction of Dresden by the air raids of February 13 and 14, 1945 . RAF-Air Vice-Marshal Don Bennet described the optimized "fan bombing technique" , which was used in this attack on Braunschweig, as a decisive preliminary stage for the destruction of Dresden in the attack evaluation and assessment that followed.

Statistics of a destruction

Population and Fatalities

At the beginning of the Second World War, Braunschweig had 202,284 inhabitants; at the end of the war this number had decreased by 26.03% to 149,641. According to contemporary data, a total of 2,905 people died as a result of the effects of war, mainly bombing and their consequences, such as the removal and defusing of duds , of whom 1286 were foreigners, i.e. 44.3%. Most of these foreigners were prisoners of war , forced laborers and concentration camp inmates . In mid-1944 there were around 51,000 foreigners in the Braunschweig employment office. a. worked in arms factories like Büssing , MIAG and NIMO . They were forbidden from entering bunkers and air raid shelters, which explains the high number of bomb victims among this group. Today's estimates assume a total number of about 3,500 dead.

Destruction of living space, infrastructure, etc.

Between 1940 and 1945 Braunschweig was the target of air raids by the RAF and the USAAF 42 times . The 42 attacks were divided into 12 individual attacks, 10 light, 8 medium and 10 heavy, with day and night attacks being balanced.

Exact (re) figures are only available for destroyed houses and apartments. In his o. G. In the situation report, the attorney general quoted the following figures for October 15, 1944: 15,776 residential buildings in total, of which were damaged as a result of the firestorm or the impact of bombs that night: 3,600 buildings completely destroyed, 2,000 seriously, 1,800 moderately and 1,400 slightly damaged. Seven months later, at the end of the war, only around 20% were completely intact, 25% were 100% destroyed and around 55% were partially damaged (the degree of destruction varied widely). In 1943, before the extensive bombing of Braunschweig, there were 15,897 houses in the city, of which only 2,834 (approx. 18%) were undamaged in mid-1945. There were 59,826 apartments, of which only 11,153 were intact at the end of the war (approx. 19%). The total degree of destruction of the residential buildings was 35%. This in turn meant that almost 80% of the city's population were homeless at the end of the war. 60% of the cultural sites (including the administration building) were also destroyed, as well as around 50% of the industrial facilities.

Total degree of destruction and amount of debris

The degree of destruction in the Braunschweig city center (within the Okerring) was 90% at the end of the war, the total degree of destruction in the city was 42%. The total amount of debris was 3,670,500 m³. This makes Braunschweig one of the most badly damaged German cities.

post war period

reconstruction

On June 17, 1946, the rubble clearance officially began in Braunschweig. It lasted 17 years - it was not until 1963 that the city officially declared the clean-up work over. In fact, however, they continued on a smaller scale decades later. 14 years after the end of the war, at the beginning of June 1959, the last known duds in the urban area were removed. But even decades later, bombs of all types and sizes are still being found in the city and its outskirts. B. the find in the city center on the site of the former castle park : On June 7, 2005, an aircraft bomb was found there. 10,000 people had to be evacuated from the city center before the dud could be transported away for defusing . At around 11:30 a.m. on July 20, 2015, a 500 kg bomb, probably from 1944, was discovered during excavation work in the immediate vicinity of Braunschweig Central Station. Since the excavator had unintentionally moved the bomb and damaged one of the detonators , it was decided to defuse the dud on the same day. At 5 p.m., the evacuation of 11,000 residents (including from the Marienstift ) within a kilometer of the site, road and rail traffic was diverted, and the main train station was closed. It was the largest evacuation measure in the history of the city of Braunschweig . The disarming was completed shortly after 11:00 p.m.

The most recent defusing took place in the night of 11/12. April 2018. On the same day, during construction work in the southern part of the city, at the intersection of Hennebergstrasse and Wolfenbütteler Strasse, an excavator came across a US 250-kg bomb with two detonators. Since the excavator had touched the bomb, it had to be defused on site immediately. From 9:00 p.m. on April 11, 8,400 residents and 2,000 hotel guests were temporarily evacuated within a radius of one kilometer. Although a heavy thunderstorm was discharging over the city at the same time, the defusing process was successfully completed around 3:00 a.m.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the reconstruction of the city made rapid progress because there was an urgent need for housing, the infrastructure had to be restored and the economy revived. Since the city center was largely a desert of rubble, new urban planners and architects seized their chance and designed and built the new, modern, and v. a. " Car-friendly city ", where u. a. the maxims of the so-called " Braunschweiger Schule " under the architects Kraemer , Oesterlen and Henn followed. This in turn led to further destruction in many places ( e.g. by newly created road aisles) or the removal of the historically grown urban landscape . In some cases, the earlier city layout was ignored, damaged buildings, instead of being repaired, were often torn down prematurely and traffic - especially motor vehicles - was raised to the standard of the "new" Braunschweig. This gave the impression of a "second destruction" of Braunschweig , especially in the city center .

This subsequent destruction of historical buildings and cultural assets in times of peace, such as For example, the demolition of numerous medieval, baroque and classicist buildings or the controversial demolition of the damaged Braunschweig Palace in the summer of 1960, similar to the Berlin City Palace and other prominent buildings in other German cities, led to a further loss of identity of the local population and was a reason for for decades very controversial discussions.

The (re) construction of damaged or destroyed buildings continues to the present. B. The old scale that was destroyed in 1944 was completely rebuilt. The most recent example is the partial reconstruction of the facade of the Braunschweig Palace in the years 2005–2007.

Commemoration

The sense and necessity of destruction

Early on during the Second World War, the Anglican bishop and member of the British House of Lords George Bell took the view that bombing raids on German cities of this magnitude threatened the ethical foundations of Western civilization and ruined the chances of future reconciliation between the war opponents. He expressed his concerns several times in speeches in the House of Lords, for example: B. 1944:

How can the War Cabinet fail to see that this progressive devastation of cities is threatening the roots of civilization?

“ How can it be that the War Cabinet does not recognize that this continuing devastation of the cities threatens the roots of civilization? "

From a post-war perspective and v. a. Against the background of the British Area Bombing Directive , the question arises as to whether the goal of large-scale, even final destruction of Braunschweig in October 1944 was militarily sensible on the one hand and necessary in view of the final phase of the war on the other. This debate is carried out in a similar form with regard to the destruction of Cologne , Hamburg , Dresden , Pforzheim , Essen , Duisburg and other cities.

Artistic processing

Shortly after the bombing, painter and NSDAP member Walther Hoeck created what is probably his best-known painting, The Burning Braunschweig . Hoeck had probably witnessed the attack himself or saw it from his former home in Lehndorf , a district of Braunschweig.

Six versions of the painting that differ only slightly from one another are known today. All are undated and in all probability were made between October 1944 and probably 1946. The largest of these pictures, measuring 124.5 cm × 204.4 cm, is now owned by NORD / LB in Braunschweig. The smallest is about half the size and privately owned. One copy is on display in the Altstadtrathaus , a branch of the Braunschweig City Museum .

All paintings show the blazing silhouette of the city when viewed from a great distance, with no people or animals to be seen in any of the paintings. Hoeck staged the firestorm as an apocalyptic inferno, a huge catastrophe that developed its own aesthetic in its destructive power. In the sea of flames shown, only a few, but characteristic points of reference and identification of the city can be seen, such as the towers of the Andreas , Katharinen and Michaeliskirche as well as those of the Brunswick Cathedral (see under “Weblinks”). For many Braunschweig residents, the burning Braunschweig is still the epitome of the destruction of their city.

Karl Wollermann , formerly one of the highest Nazi cultural functionaries and director of the Braunschweiger Werkkunstschule since the end of 1951 , created a tapestry after the end of the war that thematized the fall of Braunschweig. Today it is owned by the city.

October 15th as a fixed point in the city's history

Since then, every 14./15. October memorial events and exhibitions take place. The events of those days also found a strong echo in local historical literature.

In 1994, on the 50th anniversary of the bombing, the exhibition Braunschweig in the bombing war took place in the Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum , along with numerous other commemorative events . Almost 10,000 visitors were counted within the first week. In the same year, three extensive publications and contemporary witness reports by R. Prescher (in a new edition), E. Grote and G. Starke (see below "Literature") appeared. On October 15, 2004, the 60th anniversary of the destruction, there was an exhibition entitled October 14, 1944 - 60 Years of the Destruction of Braunschweig. Braunschweig press and culture of remembrance . In Brunswick Cathedral of the British ambassador of musicians and singers from Braunschweig and from the English was in the presence of twinned Bath , the War Requiem by Benjamin Britten listed.

In 2019, on the 75th anniversary of the bombing, there will again be numerous commemorative and information events in the city. So z. B. from September 15th to October 15th the exhibition October 15th. The destruction of the city of Braunschweig. It is spread over six locations in the city: Städtisches Museum , Jakob-Kemenate , Kemenate Hagenbrücke , Bankhaus Löbbecke , Augustinum and Andreaskirche . On display are works by artists who captured the destruction and the ruins of October 15, 1944, but also the reconstruction in etchings, watercolors, graphics, oil paintings and drawings. The exhibited artists include: Herman Flesche , Wilhelm Frantzen , Hedwig Hornburg , Günther Kaphammel , Bruno Müller-Linow , Peter Lufft , Karl-Heinz Meyer , Ernst Straßner , Daniel Thulesius and Herbert Waltmann ; but anonymous works can also be seen. Some of the works come from a private collection, some from the Municipal Museum.

A memorial has been located at the main cemetery in Braunschweig, where many victims are buried, since November 1962.

See also

literature

Magazines and documents

- Braunschweiger Zeitung (ed.): The bomb night. The aerial warfare 60 years ago , special issue No. 10, Braunschweig 2004.

- Peace Center Braunschweig e. V. (Ed.): Braunschweig in the bombing war. 50 years later. Dedicated to the victims of the war. Volume 1: Documents for the exhibition 09/30 - 10/31/1993 , Braunschweig 1994, 4th, improved edition 2004.

- ders .: Braunschweig in the bombing war. 50 years later. Dedicated to the victims of the war. Volume 2: Documents from contemporary witnesses: "Bombs on Braunschweig" . State Museum September 11–16. October 1994, Braunschweig 1994.

- ders .: Braunschweig in the bombing war. 50 years later. Dedicated to the victims of the war. Volume 3: Documents from the Memorial Night October 14/15, 1994: “The Gerloff Reports” , Braunschweig 1994, 2nd, improved edition Braunschweig 2006.

- ders .: Braunschweig in the Second World War. Documents of Destruction - Zero Hour - New Beginning In: Work reports from the Städtisches Museum Braunschweig, No. 65; Braunschweig 1994.

Monographs

- Hartwig Beseler , Niels Gutschow: War fates of German architecture. Loss, damage, rebuilding. Volume I: North. Karl Wachholtz, Neumünster 1988, ISBN 3-926642-22-X , pp. 202-231.

- Eckart Grote: Braunschweig in the air war. Allied film, photo and operational reports from the US Air Force / British Royal Air Force from 1944/1945 as documents relating to the history of the city. Braunschweig 1983, ISBN 3-924342-00-8 .

- Eckart Grote: Target Brunswick 1943-1945. Air raid target Braunschweig - documents of destruction. Braunschweig 1994, ISBN 3-9803243-2-X .

- Peter Neumann: Braunschweig as a bomb target. From records from 1944 and 1945 , in: Braunschweigisches Jahrbuch , Volume 65, Braunschweig 1984.

- Rudolf Prescher : The red rooster over Braunschweig. Air raid protection measures and aerial warfare events in the city of Braunschweig from 1927 to 1945 , Braunschweig 1955.

- Günter KP Starke: The Braunschweig Inferno and the time after. 4th expanded edition, Appelhans Verlag, Braunschweig 2002, ISBN 3-930292-58-0 .

Accounts from contemporary witnesses

- Anja Hesse, Annette Boldt-Stülzebach (eds.): The night when the bombs fell. Contemporary witnesses remember the 14./15. October 1944. Johann Heinrich Meyer Verlag, Braunschweig 2010, ISBN 978-3-926701-80-0 .

- Hedda Kalshoven: I think about you so much . A German-Dutch correspondence 1920–1949. Luchterhand Verlag, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-630-86849-5 .

- Eckhard Schimpf : At night when the Christmas trees came. A normal Braunschweig childhood in the chaos of the war and the post-war period. Braunschweiger Zeitungsverlag, Braunschweig 1997.

Film documentaries

- Braunschweig 1945 - bombing, liberation, life in ruins . recalls and comments by Eckhard Schimpf . Braunschweiger Zeitung and Archiv Verlag, Braunschweig 2005 (39m05s)

- Firestorm - The bombing war against Germany. DVD edition, SPIEGEL TV history. Polar Film , Gescher 2003 (contains excerpts from the original RAF film of the bombing on October 15, 1944)

Web links

- Film recordings of old Braunschweig before the destruction (with an interview with contemporary witnesses)

- Bunker recordings (with eyewitness interview)

- Original footage of the bombing on October 15, 1944 (aerial photos)

- Original footage of the bombing on October 15, 1944 (ground footage)

- Chronological list of the bombing raids on Braunschweig (with number of victims)

- "The burning Braunschweig" ( Memento from May 14, 2007 in the Internet Archive ), painting by Walther Hoeck (from the Internet Archive )

- "Braunschweig reinforcement" for bunkers ( Memento from September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- Andreas Döring : February 10, 1941: Bombs on Braunschweig . NDR 1 Lower Saxony ; Radio feature

- 70 years ago: Hail of bombs on Braunschweig . ndr.de, October 14, 2014

Individual evidence

- ↑ Rudolf Prescher: The red rooster over Braunschweig. Air raid protection measures and aerial warfare events in the city of Braunschweig 1927 to 1945 , Braunschweig 1955, p. 88.

- ↑ a b c Braunschweiger Zeitung (ed.): The bomb night. The air war 60 years ago. Braunschweig 2004, p. 8.

- ↑ Jörg Friedrich : The fire. Germany in the bombing war 1940–1945 . P. 83.

- ^ Eckart Grote: Target Brunswick 1943–1945. Air raid target Braunschweig - documents of destruction. Braunschweig 1994, p. 11.

- ↑ Werner Girbig: 1000 days over Germany. The 8th American Air Force in World War II , Munich 1964, p. 198 ff.

- ↑ a b c Gerd Biegel (Ed.): Bomben auf Braunschweig , in: Publications of the Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum , No. 77, Braunschweig 1994, p. 9.

- ↑ Rudolf Prescher: The red rooster over Braunschweig. Air raid protection measures and aerial warfare in the city of Braunschweig 1927 to 1945 , Braunschweig 1955, p. 111.

- ^ Merger of the companies Grotrian-Steinweg and Wilke-Werke.

- ↑ a b c d Gerd Biegel (Ed.): Bombs on Braunschweig. In: Publications of the Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum . No. 77, Braunschweig 1994, p. 28.

- ↑ Braunschweiger Zeitung (ed.): The bomb night. The air war 60 years ago. Braunschweig 2004, p. 15.

- ↑ a b Eckart Grote: Target Brunswick 1943–1945. Air raid target Braunschweig - documents of destruction. Braunschweig 1994, p. 35.

- ^ Eckart Grote: Target Brunswick 1943–1945. Air raid target Braunschweig - documents of destruction. Braunschweig 1994, p. 36.

- ^ Eckart Grote: Target Brunswick 1943–1945. Air raid target Braunschweig - documents of destruction. Braunschweig 1994, p. 101.

- ^ Eckart Grote: Target Brunswick 1943–1945. Air raid target Braunschweig - documents of destruction. Braunschweig 1994, p. 119.

- ^ RAF war diary ( Memento from May 10, 2005 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Braunschweiger Zeitung (ed.): The bomb night. The air war 60 years ago. Braunschweig 2004, p. 43.

- ↑ Dieter Diestelmann: The night in which fire fell from the sky , special supplement of the Braunschweiger Zeitung on the 40th anniversary of the bombing of October 13, 1984, p. X.

- ↑ a b c d e Eckart Grote: Target Brunswick 1943–1945. Air raid target Braunschweig - documents of destruction. Braunschweig 1994, p. 118.

- ↑ Jörg Friedrich : The fire. Germany in the bombing war 1940–1945 . Munich 2002, p. 236.

- ↑ Fish code names (PDF; 292 kB) British original, German translation (PDF; 214 kB), on: bunkermuseum.de ( Bunkermuseum Emden ), accessed on October 2, 2017

- ↑ a b Eckart Grote: Target Brunswick 1943–1945. Air raid target Braunschweig - documents of destruction. Braunschweig 1994, p. 124.

- ↑ Dieter Diestelmann: The night in which fire fell from the sky , special supplement of the Braunschweiger Zeitung on the 40th anniversary of the bombing of October 13, 1984, p. XI f.

- ↑ Note: The maximum bomb load on a Lancaster was just over six tons. The indication of the bomb load "1 × 1000 MC / GP (1000 pounds corresponds to 453 kg) plus maximum incendiary bombs" means that the bomb hold was filled with incendiary bombs up to the maximum permitted take-off weight , taking into account the required amount of fuel. It can therefore be assumed that the Lancaster's cargo for this attack on Braunschweig consisted of more than 80% incendiary bombs.

- ↑ a b Eckart Grote: Target Brunswick 1943–1945. Air raid target Braunschweig - documents of destruction. Braunschweig 1994, p. 121.

- ↑ a b Eckart Grote: Target Brunswick 1943–1945. Air raid target Braunschweig - documents of destruction. Braunschweig 1994, p. 120.

- ↑ Dieter Diestelmann: The night in which fire fell from the sky , special supplement of the Braunschweiger Zeitung on the 40th anniversary of the bombing of October 13, 1984, p. III.

- ↑ Dieter Diestelmann: The night in which fire fell from the sky , special supplement of the Braunschweiger Zeitung on the 40th anniversary of the bombing of October 13, 1984, SI

- ^ Eckart Grote: Target Brunswick 1943–1945. Air raid target Braunschweig - documents of destruction. Braunschweig 1994, p. 129.

- ↑ Braunschweiger Zeitung (ed.): The bomb night. The air war 60 years ago. Braunschweig 2004, p. 37.

- ↑ a b Rudolf Prescher: “The red rooster over Braunschweig. Air raid protection measures and air war events in the city of Braunschweig 1927 to 1945 ”, Braunschweig 1955, p. 90.

- ↑ a b Eckart Grote: Target Brunswick 1943–1945. Air raid target Braunschweig - documents of destruction. Braunschweig 1994, p. 123.

- ^ Royal Air Force Bomber Command 1942–1945 , photos from the Imperial War Museum , London at iwm.org.uk.

- ↑ a b Braunschweiger Zeitung (ed.): The bomb night. The air war 60 years ago. Braunschweig 2004, p. 39.

- ↑ a b c Braunschweiger Zeitung (ed.): The bomb night. The air war 60 years ago. Braunschweig 2004, p. 42.

- ↑ a b Rudolf Prescher: “The red rooster over Braunschweig. Air raid protection measures and air war events in the city of Braunschweig 1927 to 1945 ”, Braunschweig 1955, p. 92.

- ↑ Braunschweiger Zeitung (ed.): The bomb night. The air war 60 years ago. Braunschweig 2004, p. 30.

- ^ Entry in the war diary of the Royal Air Force Bomber Command for October 15, 1944 ( Memento of May 10, 2005 in the Internet Archive ): Total tonnage of bombs dropped in 24 hours: approximately 10,050 tons. These record totals would never be exceeded in the war. (Total amount of bombs dropped within 24 hours: approx. 10,050 tons. This record amount was not exceeded during the war.)

- ↑ Inauguration of the memorial plaque on August 25, 2012 ( Memento of the original from October 21, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Braunschweiger Zeitung (ed.): The bomb night. The air war 60 years ago. Braunschweig 2004, p. 57.

- ↑ Braunschweiger Zeitung (ed.): The bomb night. The air war 60 years ago. Braunschweig 2004, p. 56 f.

- ^ Edeltraut Hundertmark: Stadtgeographie von Braunschweig In: Research on regional and folklore. I: nature and economy. Writings of the economic society for the study of Lower Saxony e. V. , New Series, Volume 9, Oldenburg 1941, p. 86.

- ↑ a b c Letter from the Braunschweig Chief Public Prosecutor of January 25, 1945

- ^ Eckart Grote: Braunschweig in the air war. Allied film, image and operational reports of the US Air Force / British Royal Air Force from 1944/1945 as city history documents. Braunschweig 1983, p. 40.

- ↑ Eckart Schimpf: At night when the Christmas trees came. A perfectly normal Braunschweig childhood in the chaos of the war and post-war period , Braunschweig 1998, p. 81.

- ↑ Rudolf Prescher: The red rooster over Braunschweig. Air raid protection measures and aerial warfare in the city of Braunschweig 1927 to 1945 , Braunschweig 1955, p. 95.

- ^ Theodor Müller: Ostfalenland. A local history of the country between Harz, Weser and Aller , Braunschweig 1961, p. 47: The worst attack was the arrival of around 1000 aircraft in the night of October 14th to 15th, 1944. The city center was destroyed in a wild firestorm ...

- ↑ Jörg Friedrich : The fire. Germany in the bombing war 1940–1945 . Munich 2002, p. 375.

- ↑ Braunschweiger Zeitung (ed.): The bomb night. The air war 60 years ago. Braunschweig 2004, p. 14.

- ↑ Gerd Biegel (Ed.): Bomben auf Braunschweig , in: Publications of the Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum , No. 77, Braunschweig 1994, p. 15.

- ↑ Federal Statistical Office (Ed.): Statistical Reports, Work No. VIII / 19/1, "The civil population of the German Reich 1940–1945. Results of consumer group statistics", Wiesbaden 1953; P. 38.

- ↑ Information on the whereabouts of the downed Lancaster bomber No. 61 Squadron Lancaster I ME595 QR-Y on http://aircrewremembered.com (in English)

- ↑ 207 Squadron RAF Association

- ^ Helmut Weihsmann : Building under the swastika. Architecture of doom. Promedia Druck- und Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, Vienna 1998, ISBN 3-85371-113-8 .

- ↑ a b Braunschweiger Zeitung (ed.): The bomb night. The air war 60 years ago. Braunschweig 2004, p. 34.

- ↑ Literature on Braunschweig reinforcement.

- ↑ Jörg Friedrich : The fire. Germany in the bombing war 1940–1945. Munich 2002, p. 392.

- ↑ Braunschweiger Zeitung (ed.): The bomb night. The air war 60 years ago. Braunschweig 2004, p. 36.

- ↑ wiki-de.genealogy.net plan in the address book from 1940

- ↑ wiki-de.genealogy.net plan in the address book from 1940

- ↑ Rudolf Prescher: “The red rooster over Braunschweig. Air raid protection measures and aerial warfare events in the city of Braunschweig 1927 to 1945 ”, Braunschweig 1955, p. 96.

- ↑ Rudolf Prescher: “The red rooster over Braunschweig. Air defense measures and aerial warfare events in the city of Braunschweig 1927 to 1945 ”, Braunschweig 1955, p. 99.

- ^ Eckart Grote: Target Brunswick 1943–1945. Air raid target Braunschweig - documents of destruction. Braunschweig 1994, p. 151.

- ^ Eckart Grote: Target Brunswick 1943–1945. Air raid target Braunschweig - documents of destruction. Braunschweig 1994, p. 125.

- ^ Entry from October 15, 1944 in the RAF Bomber Command war diary ( Memento from May 10, 2005 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Rudolf Prescher: The red cock over Braunschweig. Air raid protection measures and air war incidents in the city of Braunschweig 1927 to 1945 , Braunschweig 1955, p. 114.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Ludewig: Braunschweig in the bombing war. An attempt at a historical classification , in: Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift des Braunschweigisches Landesmuseums , No. 4, Braunschweig 1997, p. 162.

- ↑ Rudolf Prescher: “The red rooster over Braunschweig. Air raid protection measures and air war events in the city of Braunschweig 1927 to 1945 ”, Braunschweig 1955, p. 111.

- ↑ Rudolf Prescher: The red rooster over Braunschweig. Air raid protection measures and aerial warfare events in the city of Braunschweig 1927 to 1945 , Braunschweig 1955, p. 112.

- ^ Wolfgang Eilers, Dietmar Falk: Narrow-gauge steam in Braunschweig. The history of the rubble railway , In: Small series of the Braunschweiger Verkehrsfreunde e. V. , No. 3, Braunschweig 1985, p. 66.

- ^ Chronicle of the city of Braunschweig for 1959.

- ↑ Braunschweiger Zeitung of June 9, 2005: 14 hours and 37 minutes - Chronicle of the bomb discovery ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ This is how the largest evacuation in the city went. In: Braunschweiger Zeitung of July 21, 2015.

- ^ Air bomb defused in Braunschweig . (with photos and videos) on NDR.de

- ↑ Map of the evacuation area of the bomb disposal from April 11, 2018 ( Memento of the original from April 12, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Thunderstorm warning for the Braunschweig area on 11/12. April 2018

- ^ Bomb disposal on 11/12. April 2018 ( Memento of the original from April 12, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Video recordings on NDR from April 12, 2018.

- ↑ George Kennedy Allen Bell: The Church and Humanity (1939-1946), Green Longmans 1946, p. 140.

- ↑ a b Braunschweig City Museum and University of Fine Arts (ed.): German Art 1933–1945 in Braunschweig. Art under National Socialism. Catalog of the exhibition from April 16, 2000–2. July 2000. Braunschweig 2000, p. 170.

- ↑ Braunschweig Municipal Museum and University of Fine Arts (ed.): German Art 1933–1945 in Braunschweig. Art under National Socialism. Catalog of the exhibition from April 16, 2000–2. July 2000. Braunschweig 2000, p. 271.

- ^ Letter from Jürgen Weber quoted from Jürgen Weber: Letters to the Editor . In: Der Spiegel . No. 46 , 1966, pp. 20–21 ( online - spiegel.de (PDF)).

- ^ Garzmann, Schuegraf, Pingel: Braunschweiger Stadtlexikon - supplementary volume . Braunschweig 1996, p. 140.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Ludewig: Braunschweig in the bombing war. An attempt at a historical classification , in: Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift des Braunschweigisches Landesmuseums , No. 4, Braunschweig 1997, p. 153.

- ^ Page of the city of Braunschweig on the events on the occasion of the 60th anniversary on October 15, 2004 ( Memento of March 12, 2008 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Florian Arnold: Impressive pictures of the destruction of Braunschweig. In: Braunschweiger Zeitung from August 31, 2019.

- ↑ The destruction of the city of Braunschweig on Braunschweig.de

- ↑ Städtisches Museum Braunschweig , Prüsse Foundation (Ed.): October 15. The destruction of the city of Braunschweig in 1944. Hinz und Kunst, Braunschweig 2019, ISBN 978-3-922618-34-8 .

- ↑ Flyer for the exhibition on braunschweig.de (pdf)

Remarks

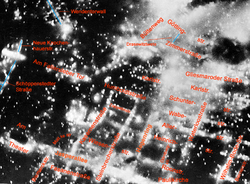

- ↑ In raking light (sun is in the West) easily recognizable: The (bright, wide) road from the bottom, obliquely running right is the Fallersleber road , which in the Hagenmarkt flows. The badly damaged Katharinenkirche is clearly visible . Following the Hagenmarkt to the right, completely destroyed areas of the city center . The three streets branching off from Fallersleber Strasse (with large-scale bombs) in the direction of Steinweg are v. l. To the right : Mauernstrasse , Schöppenstedter Strasse and Wilhelmstrasse . The Steinweg runs towards Burgplatz . The State Ministry can be seen here in Dankwardstrasse, opposite the City Hall . Dankwarderode Castle and the cathedral are visible on Burgplatz . The heavily damaged Braunschweig Castle on Bohlweg is slightly above the center of the picture . Behind it, to the south, destroyed streets around the Aegidienkirche , including Aegidienmarkt , Kuhstraße , Stobenstraße and Auguststraße . The old train station can be seen in the upper right corner. On the left edge of the picture, the State Theater is visible in the middle , and a little above the Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum . In the upper left corner is the Magniviertel with numerous destroyed and damaged buildings. For example: the badly damaged Magni Church and large areas of destroyed streets around the Ackerhof . The municipal museum , the Löwenwall and the Gauss School can also be seen .