Combined bomber offensive

The term Combined Bomber Offensive ( CBO ; German Combined Bomber Offensive ) describes the strategic aerial warfare of the Anglo-American Allies against the German Reich in World War II from 1943 to 1945. The Combined Bomber Offensive originally arose from the Allies' efforts to maintain military pressure on Germany , while Operation Overlord was being prepared, and directed against the 'German military, industrial and economic system' and the perseverance of the civilian population.

The campaign combined two initially very different strategies - the night attacks of the RAF Bomber Command against area targets and the daytime attacks of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) against point targets - into an overall strategy that resulted in the extensive destruction of almost all major German cities and numerous means by the end of the war - and led small towns.

prehistory

Air war doctrines of the participating air forces

Both the British and the Americans brought their own ideas about the strategic bombing war in Europe with them when they decided on the Combined Bomber Offensive in 1943.

The British air war doctrine, which emerged in the period after the " Blitz " and was laid down in the Area Bombing Directive of 1942, placed the emphasis on demoralizing the civilian population by bombing German cities. After several loss-making attempts with daytime attacks, the British Bomber Command switched to an almost exclusive night attack strategy early in the war.

The American Air War Doctrine, laid down in Directives AWPD-1 of 1941 and AWPD-42 of 1942, provided for daytime attacks on specific key industrial targets. Collateral damage among the civilian population should be avoided as much as possible. With the heavily armed Boeing B-17 and the Norden bomb sighting device , USAAF felt that it could meet these demands. An escort by fighter planes was initially not considered necessary, the bombers flying at high altitudes were supposed to defend each other in dense formations.

Air war theorists of both allies assumed that if not decided the war by air raids alone, then at least significantly contributing to the outcome. The effort to demonstrate the raison d'être of independent air forces also played a role.

The strategic air war until 1943

The Royal Air Force opened the strategic aerial warfare against the German Reich in May 1940 as part of the western campaign . After the bombing of Rotterdam by the German air force on May 14th, the strategic air war against German cities was authorized. Put on the defensive by the German successes (→ Battle of Britain ), air strikes became the means of choice to take the war to the enemy. However, the effectiveness of these early attacks remained poor, as disclosed in the 1941 Butt Report .

Inextricably linked with the air war of the Bomber Command against Germany is its Commander in Chief since February 1942, Air Marshal Arthur Harris . Under his leadership, the Bomber Command went over to a strategy of area bombing , as provided for in the Area Bombing Directive and the Dehousing Paper . The primary aim of these attacks was the morale of the civilian population, the disruption of which was considered an essential condition for a successful outcome to the war.

The United States Army Air Forces appeared in Europe in 1942 as the Eighth Air Force stationed in the United Kingdom . This carried out its first operations against the European continent in August 1942. Due, among other things, to charges for Operation Torch in North Africa at the end of 1942, their participation in the air war against “Fortress Europe” was initially manageable. It was not until January 27, 1943 that the Eighth Air Force flew its first attack on targets in Germany (55 bombers - Wilhelmshaven and Emden ).

The Casablanca Directive

The foundation stone for the Combined Bomber Offensive was laid at the Casablanca Conference in January 1943, at which the Allies' war plans for 1943 were discussed. In the directive CCS 166/1 / D of the Combined Chiefs of Staff of January 21, 1943, which was largely drafted by the British Air Vice Marshal John Slessor , the goal was set:

“(...) Your primary object will be the progressive destruction and dislocation of the German military, industrial, and economic system, and the undermining of the morale of the German people to a point where their capacity for armed resistance is fatally weakened. (...) ”

"Their primary goal will be the increasing destruction and disruption of the German military, industrial and economic system and the undermining of the morale of the German people to the point where their ability to armed resistance is decisively weakened."

The primary goals were defined:

- Submarine yards

- the aircraft industry

- Transport destinations

- Oil extraction and processing

- further goals of the war industry

The chief of the British air staff , Air Chief Marshal Charles Portal , was charged with coordinating the air offensive between the British and the Americans . The very general directive gave both sides the opportunity to pursue their respective strategic concepts largely independently of one another.

Creation of the CBO plan and point blank directive

The Commander-in-Chief of the United States Army Air Forces, General Henry H. Arnold , had formed his own Committee of Operations Analysts (COA) in the run-up to the Casablanca Conference in December 1942 to identify weak points in the German industrial system. The experts submitted their final report on March 8, 1943, which proposed nineteen sectors of the German economy for destruction. According to the "industrial web theory", the elimination of individual key sectors of the German economy would be enough to decisively paralyze German war production. On the basis of this report, taking into account the recommendations of the British Ministry of Economic Warfare , the British Air Staff and the Eighth Air Force, a list of 76 primary targets was compiled in six categories, which were prioritized as follows:

- Submarine yards and bases

- Aircraft industry

- Ball bearings

- synthetic oil

- Rubber and tires

- military transport vehicles

On this basis, an Anglo-American committee headed by Haywood S. Hansell worked the "plan for the combined bomber offensive from the United Kingdom" ("CBO plan", also "Eaker plan", after Ira C. Eaker , the commander in chief of the Eighth Air Force). In this a sequence of attacks was determined and the number of bombers required was determined. According to the plan, the American bomber forces in the United Kingdom were to be brought to a strength of over 2,700 heavy bombers by the end of March 1944. The reduction of the German day-hunting forces was named as the intermediate objective with the highest priority. On April 29, the plan was presented by Eaker to the Joint Chiefs of Staff and, with minor modifications, approved by the Combined Chiefs of Staff on May 14 at the Washington Trident Conference . On June 10, the Pointblank Directive , as the plan was now called, was issued to the relevant commanders. A Combined Operational Planning Committee chaired by Brigadier General Orvil A. Anderson was set up to coordinate the point blank offensive .

course

1943

When the Combined Bomber Offensive officially began on June 10, 1943, the Bomber Command had been involved in the Battle of the Ruhr for three months , which continued until the end of July. Harris had opened the “Battle for the Ruhr Area” when the oboe navigation aid was ready, the range of which just covered the Ruhr area. Aircraft of the Pathfinder Force , which was set up in the summer of 1942, used the system to mark the target with flares for the following bomber formations . The H2S ground penetrating radar was used when visibility was poor .

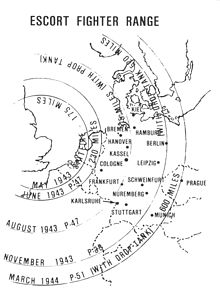

In the absence of an escort fighter capable of reaching targets deep in Germany, the Eighth Air Force was mainly engaged in attacks on German submarine yards and bases on the coasts of France, the Netherlands and Germany until the summer of 1943. On June 11, the "Eighth" flew an attack on Germany with more than 200 four-engine bombers for the first time. On June 22nd, the USAAF launched its first large daytime attack on the Ruhr area. The destination was the Hüls chemical works . The Eighth Air Force had begun attempts in May 1943 to convert the Boeing B-17 into a heavily armed escort gunship ( Boeing YB-40 ). This was little more than an embarrassing solution after the decision to move the twin-engined P-38 long-range fighters to the Mediterranean area had already been decided in January . This left only the P-47 for escort duties, whose range was not yet sufficient for missions over Germany. It was not until July 1943 that the first drop tanks for the Eighth Air Force P-47s became available.

The first truly combined use of both air forces took place during Operation Gomorrah at the end of July, when US bombers attacked Hamburg , which had already been badly hit by a previous British night attack, on July 25th . This was the prelude to “Blitz Week” of the Eighth Air Force, during which targets deep in Germany were attacked for the first time, including the Focke-Wulf works in Oschersleben . The “Battle of Hamburg” was the first occasion on which the British used Düppel , called by them “Window”, whereby the German radar early warning system of the Kammhuber Line suddenly became ineffective.

Operation Double Strike against Schweinfurt and Regensburg on August 17th formed the preliminary climax of the US bomber operations . The high losses suffered in the process, as well as those during a second attack on Schweinfurt in October, signaled that, contrary to predictions, missions deep in enemy territory could not be carried out successfully without escort. The attacks on ball bearing plants had been included in the CBO plan. From the American point of view, possibly decisive for the war, Harris dismissed these attacks against " panacea targets" from the start. The German arms industry was not affected. In September 1943 the first mission took place in which the US bombers deliberately “blindly” dropped their bomb load: during an attack on Emden , the H2S radar adopted by the British was used to bomb the target through a layer of cloud. Such attacks were used with increasing frequency in the autumn and winter of 1943/44 so that the bombers could still be used actively in bad weather conditions. The Americans developed the system further independently and called their version "H2X".

A turning point in the bombing war was initiated by the appearance of the long-range escort fighter P-51 on the European theater of war in December 1943. With this began the actual attainment of air supremacy over Germany by day. While the German night fighters were still able to inflict heavy losses on the British bomber units, for example during the “Battle of Berlin” from November 1943 to March 1944, the percentage losses suffered by the Americans after the setbacks of the past few months fell back to a tolerable level. At the same time, the number of USAAF bomber formations in the United Kingdom rose steadily, although, according to the calculations of the British Chief of the Air Staff Portal, which he presented to the Combined Chiefs of Staff at the Cairo conference in December, it was still three months behind Plan lagged behind. At this conference the Americans announced the formation of their own United States Strategic Air Forces in Europe (USSAFE, later USSTAF) headquarters to control their strategic bomber fleets in Europe. This took account of the fact that a new American air fleet, the Fifteenth Air Force , had started operations from Italy after the Allies had gained a foothold there. The former commander of the Eighth Air Force, General Carl A. Spaatz , received the supreme command of USSTAF .

1944

The beginning of 1944 was marked by rivalries related to the planned Operation Overlord . For the duration of this operation, the strategic bomber fleets were to be under the control of SHAEF's Commander-in-Chief , Dwight D. Eisenhower . The Allied Expeditionary Air Forces headquarters under the British Trafford Leigh-Mallory , which had meanwhile been formed , intervened in the target planning for Overlord and presented its transportation plan at the end of January . This met resistance, especially Spaatz ', who wanted to implement his Oil Plan . In essence, it was less about target priorities than about the question of how control over the heavy bomber fleets should be exercised in the future. Ultimately, both plans were implemented and proved critical to the success of the respective missions.

The most successful operation of the Combined Bomber Offensive to date was Operation Argument , better known as " Big Week " , which took place in February 1944 . The success consisted less in the intended reduction in German emissions of fighter planes (this peaked in 1944) than in forcing the Luftwaffe to defend. Due to a new tactic introduced by the Americans, General James H. Doolittle , new Commander in Chief of the Eighth Air Force, in January and which gave the escort fighters a free hand to fight the German fighters, the German losses of fighter pilots rose steadily. This bloodletting was hard to cope with for the Air Force. In search of a target that would be defended by the German day fighters, the Eighth Air Force participated in Harris' "Battle for Berlin" with several attacks in March 1944.

Another bottleneck on the German side was the supply of oil products, which Spaatz thought should be exploited. After the first air raids on Ploieşti in 1942 and 1943, Spaatz believed that a real "oil offensive" should begin against hydrogenation plants and refineries in the German sphere of influence. However, he was initially unable to assert himself. In April 1944, the management of the operations of the strategic bomber fleets came under the control of the Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Expeditionary Force, General Eisenhower, who had it carried out by his deputy Arthur Tedder . According to the Transportation Plan, there were attacks on transport targets in the occupied countries of Western Europe as well as on V-weapon facilities ( Operation Crossbow ), radar systems, coastal fortifications and airfields (see aerial warfare during Operation Overlord ). Through ultra information, Eisenhower (and the British) succeeded in convincing Eisenhower (and the British) in May of the point in an oil campaign that was officially announced by SHAEF in early June.

The first attempted attacks on oil installations in May had already caused panic among the German air force command. On May 30th, Edmund Geilenberg was appointed "General Commissioner for Immediate Measures at the Reich Minister for Armaments and War Production". His mineral oil security plan included the relocation of refineries underground . Underground relocation was also the means of choice to keep other war industries alive, such as production facilities for retaliatory weapons and jet aircraft.

The V-Waffen offensive against the United Kingdom ("Operation Lumber Room") that began on June 12th took its own toll on the Combined Bomber Offensive. The Americans could hardly ignore British demands for countermeasures, so that a considerable part of the available flight days in the summer of 1944 had to be invested in neutralizing the V-weapons threat. It also seemed necessary to have the heavy bombers set in motion the halting advance of the ground troops in Normandy. However, both meant only a temporary interruption of the air offensive against the German Reich. At the Second Québec Conference in September it was decided to return the bomber fleets to the Combined Chiefs of Staff. Portal and Henry H. Arnold , the commander in chief of the USAAF, were to lead the bombing war, on whose behalf the Deputy Chief of the Air Staff Norman Bottomley and Spaatz acted as chiefs of USSTAF.

After the rapid advance through France, US ground troops reached the border of the German Reich on September 10, and a little later Operation Market Garden to cross the Lower Rhine failed. The advance of the Allies came to a halt at the Siegfried Line and natural obstacles. This presumably prevented Operation Thunderclap , a planned massive air raid on Berlin with all available aircraft that was supposed to kill over 100,000 civilians and bring the German Reich to surrender.

At the end of September, Bottomley and Spaatz agreed on the “Strategic Bombing Directive No. 1". In it, oil targets were given the highest priority, followed by arms targets. Bad weather destinations should be industrial cities that could be found with the available navigation aids. To select the most suitable targets, the Combined Strategic Targets Committee was formed in October , chaired by Sydney Bufton . At the end of October, a second directive followed with slightly different priorities: The Allies had recognized that transport targets had a potential similar to oil targets to paralyze the German military-industrial system. The reduced transport of coal from the Ruhr area had already led to bottlenecks in energy generation and, together with the destruction of important railway lines, posed ever greater problems for the Reichsbahn . As a consequence, attacks on armaments targets were rejected unless they were expressly requested by the commanders of the ground forces.

In the fall and winter of 1944, bad weather made radar operations the norm instead of the exception. In the last quarter of 1944, they made up between 70 and 80 percent of all missions in the USAAF. The attacks on targets such as marshalling yards were effective but very imprecise and led to massive destruction of the surrounding cities. The Battle of the Bulge , which began on December 16, forced the Allied bomber fleets to undertake a large number of operations to support the ground troops until January 1945.

1945

On January 12th, Directive No. 3 for the Strategic Air Forces in Europe , which responded to fears within the Air Forces about German jet jets, but also about the Navy about new German submarine types. This was changed at the Malta Conference at the end of January so that traffic centers in eastern Germany such as Berlin, Leipzig and Dresden were added to the target list with the second highest priority after oil. This was intended to signal to the Soviets their readiness to support their winter offensive . The endeavor to exploit and increase the chaos caused by the mass evacuations from the east also played a role. The traffic situation in Germany was also to be aggravated by a large-scale wave of attacks on small towns that had not been bombed so far. It was hoped that this would also be a demonstration of the power of the Allied bomber fleets in the countryside that had so far been little affected by the bombing. The consequences of these plans included the devastating air raids on Dresden and Operation Clarion in February. The latter was supposed to support the offensive of the ground troops to the Rhine and was flown by all available aircraft including fighters - a total of over 9,000 machines.

In March 1945 the strategic aerial warfare reached its climax after the bombs had been dropped, which - despite the jet fighter - was due to the fact that there was hardly any resistance from the Luftwaffe. For reasons unknown today, on March 28, after the Allied armies had successfully crossed the Rhine , the British Prime Minister Churchill demanded in a note to Portal that the area attacks against cities be stopped:

“The moment has come when the question of bombing German cities simply for the sake of increasing the terror, though under other pretexts, should be reviewed. Otherwise, we shall come into control of an utterly ruined land. The destruction of Dresden remains a serious query against the conduct of Allied bombing. I am of the opinion that military objectives must henceforward be more strictly studied in our own interests rather than that of the enemy. The Foreign Secretary has spoken to me on this subject, and I feel the need for more precise concentration upon military objectives such as oil and communications behind the immediate battle zone, rather than on mere acts of terror and wanton destruction, however impressive. "

“The time has now come when the question of bombing Germany should only be reconsidered for the sake of increasing terrorism, albeit under other pretexts. Otherwise we would occupy a completely destroyed country. The destruction of Dresden remains a serious point of criticism against the conduct of the Allied bombings. I am of the opinion that, in the future, military objectives must be examined more closely in relation to our own interests than those of the enemy. The State Department has spoken to me about this issue and I think there needs to be a closer focus on military targets like oil and communications beyond the immediate war zone, as opposed to mere acts of terrorism and wanton destruction, however impressive these may be. "

On April 6, the strategy of area bombing by the Bomber Command was officially ended, with the exception of military operations. On April 12, Spaatz and Bottomley ordered in their last strategic directive (No. 4) that from now on the bomber fleets should only support the operations of the ground forces. This also included the “riot bombs” of cities.

The last attacks of the war by the four-engine bomber fleets operating from England took place on 25/26. April, including an attack on Hitler's Berghof . The Bomber Command then used its planes for the repatriation of British prisoners of war ( Operation Exodus ), as well as with the Eighth Air Force for the dropping of food over the still occupied Netherlands ( Operations Manna and Chowhound ). The last strategic mission of the Fifteenth Air Force in Europe was flown against Salzburg on May 1st , followed by the last bombing raid of the Bomber Command against Kiel on May 2nd .

Balance sheet

The results of the Combined Bomber Offensive were evaluated after the war by the United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS) and the British Bombing Survey Unit (BBSU). Both came to the conclusion that the campaign had been largely ineffective until early 1944, but had been a decisive factor in the victory over Germany thereafter. The campaigns against oil and transport targets were rated as crucial campaigns. According to the USSBS, the crushing of the air force by US escort fighters was a necessary prerequisite. The apparent paradox of the increase in German armaments production with simultaneous intensification of the bombing war (see armaments miracle ) was recognized by the Allied experts, but a decisive influence on the outcome of the war was prevented by other factors.

The consequences of the CBO for the German civilian population were grave. The human losses cannot be clearly quantified. In a publication by the Federal Statistical Office from the 1950s, the number of bomb deaths on the territory of the German Reich within the borders of 1942 was estimated at 635,000. Today it is assumed that during the entire Second World War between 360,000 and 465,000 people in the German Reich within the borders of 1937 (including foreigners - forced laborers, prisoners of war, etc. - and Wehrmacht soldiers) lost their lives, the vast majority of them in the years of CBO (1943 to 1945). About 40% of the German residential substance in cities with over 20,000 inhabitants was destroyed, with corresponding effects such as extensive evacuations. In large cities this rate could reach 70%, in some medium-sized and small towns it could reach 80 to 100%. The USSBS estimates that over 7.5 million Germans have been left homeless. Around 400 million cubic meters of rubble had to be removed.

The damage to cultural assets was also immense. The cityscape of many cities changed permanently due to the loss of historical building fabric. Many medieval city centers with culturally significant buildings such as churches and city castles were irretrievably lost. Museums, art collections and event buildings were also badly hit. According to estimates, the German libraries lost at least a third of their 75 million volumes despite extensive outsourcing.

See also

literature

- Horst Boog , Gerhard Krebs , Detlef Vogel: The German Reich and the Second World War . Volume 7: The German Reich on the Defensive - Strategic Air War in Europe, War in the West and in East Asia 1943 to 1944/45. Edited by the Military History Research Office , Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 978-3-421-05507-1 .

- Richard G. Davis: Bombing the European Axis Powers: A Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive, 1939-1945. Air University Press, Maxwell AFB 2006 ( online ).

- Robert Ehlers: Targeting the Third Reich: Air Intelligence and the Allied Bombing Campaigns. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence KS 2009, ISBN 978-0-7006-1682-4 .

- Jörg Friedrich : The fire. Germany in the bombing war 1940–1945. Propylaea, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-549-07165-5 .

- Olaf Groehler : bombing war against Germany. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-05-000612-9 .

- Randall Hansen : Fire and Fury: The Allied Bombing of Germany, 1942-1945. NAL Caliber, New York 2009, ISBN 978-0-451-22759-1 .

- Alan J. Levine: The Strategic Bombing of Germany, 1940-1945. Praeger, 1992, ISBN 0-275-94319-4 .

- Robin Neillands : The War of the Bombers: Arthur Harris and the Allied Bomber Offensive 1939–1945. Translated from the English by Kurt Baudisch, Edition q, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-86124-547-7 .

- Richard Overy : The Bomb War. Europe 1939–1945. Translated from the English by Hainer Kober, Rowohlt, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-87134-782-5 .

- Ronald Schaffer: Wings of Judgment: American Bombing in World War II. Oxford University Press, 1985, ISBN 0-19-503629-8 .

- Charles Webster, Noble Frankland : The Strategic Air Offensive against Germany, 1939-1945. 4 vols., HMSO , London 1961.

Footnotes

- ↑ Mark Clodfelter: Pinpointing Devastation: American Air Campaign Planning before Pearl Harbor. In: The Journal of Military History , Vol. 58, No. 1 (Jan. 1994), pp. 75-101.

- ^ United States Department of State: Foreign relations of the United States. The Conferences at Washington, 1941-1942, and Casablanca, 1943. pp. 781 f.

- ↑ Overy: The Bomb War. Rowohlt 2014, p. 441.

- ↑ Wesley Frank Craven, James Lea Cate: The Army Air Forces in World War II, Vol. II - Europe: Torch to Pointblank, August 1942 to December 1943. P. 364 f.

- ↑ See John F. Kreis (Ed.): Piercing the Fog: Intelligence and Army Air Forces Operations in World War II. Air Force History and Museums Program, Washington DC 1996, ISBN 0-16-048187-2 , p. 237 ff. and Francis Hinsley (ed.): British Intelligence in the Second World War: Its Influence on Strategy and Operations. Vol. 3, Part 2. HMSO, London 1988. ISBN 0-11-630940-7 , p. 500 ff.

- ↑ Wesley Frank Craven, James Lea Cate: The Army Air Forces in World War II, Vol. III - Europe: Argument to VE Day, January 1944 to May 1945. P. 179.

- ↑ Wesley Frank Craven, James Lea Cate: The Army Air Forces in World War II, Vol. III - Europe: Argument to VE Day, January 1944 to May 1945. P. 667.

- ^ Charles Webster, Noble Frankland: The Strategic Air Offensive against Germany, 1939-1945. Vol. 3, HMSO, London 1961., p. 112.

- ↑ United States Strategic Bombing Survey: The United States Strategic Bombing Survey. A collection of the 31 most important reports printed in 10 volumes. With an introduction by David MacIsaac. Garland, New York 1976, ISBN 0-8240-2026-X .

- ^ British Bombing Survey Unit: The Strategic Air War Against Germany, 1939-1945: Report of the British Bombing Survey Unit. With forewords by Michael Beetham and John W. Huston and introductory material by Sebastian Cox. Cass, London 1998, ISBN 0-7146-4722-5 .

- ↑ Hans Sperling: The air war losses during the Second World War in Germany , in: Economy and Statistics , October 1956, ed. from the Federal Statistical Office, pp. 498–500.

- ↑ Ralf Blank u. a .: The German Reich and the Second World War, Volume 9/1: The German War Society 1939 to 1945 - First half volume: Politicization, Destruction, Survival. On behalf of the MGFA ed. by Jörg Echternkamp , Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 2004, XIV, 993 pp. ISBN 978-3-421-06236-9 , pp. 459 ff.

- ^ Hermann Glaser : 1945: Beginning of a future. Report and documentation. Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, 2005, ISBN 3-596-16649-7 , p. 135