Air raids on Nordhausen

From April 1944 to April 1, 1945 the American Air Force attacked the air base and the city of Nordhausen several times with a total of 296 tons of bombs. On April 3 and 4, 1945, a week before the US Army invaded Nordhausen , the Bomber Command of the British Royal Air Force carried out two devastating air raids with 2,386 tons of bombs. They destroyed over 75% of the district town on the southern Harz and claimed at least 8,800 lives. It was the greatest catastrophe in the thousand-year history of Nordhausen.

Nordhausen before the air raids

The city of Nordhausen, south of the Harz Mountains, had 42,000 inhabitants before the Second World War. As a result of non-residents (evacuated from the air war, refugees, foreign workers, wounded and prisoners of war), their number had risen to 65,000 inhabitants at the beginning of March 1945. The city of Nordhausen and the district were designated as reception rooms, particularly for evacuees from Berlin, Hamburg and West Germany. Nordhausen had no older tradition as a garrison. In the mid-1930s, the large facility of the “Luftnachrichten-Schule 1”, the “ Boelcke Barracks”, with classrooms, accommodation and vehicle hangars, was built in the south of the city . South of the city built the Air Force an air base as a training course and temporarily Flugzeugwerft. Until mid-March 1945 aircraft for mistletoe tow ("piggyback" aircraft) were assembled here and pilots trained for it. Otherwise, in 1945 the air base was used to refuel fighter planes during stopovers. The evacuated "Marineverwaltung West" was in temporary accommodation in the city. There were many military hospitals with a total of around 1,000 wounded in the city and its immediate vicinity . The military hospitals and hospitals had large Red Cross symbols on the roofs that were visible from afar. As part of air raid protection , air raid shelters , with wall breakthroughs to neighboring cellars, public air raid shelters from late summer 1943 (as the actual air raid shelter, only the rock cellar in the enclosure was completed until February 1945), concrete and covered splinter ditches and ponds for fire fighting , were also built in the half-timbered town of Nordhausen . There was an air warning command of the Luftwaffe (FLUKO), but at the beginning of April 1945 there was no more anti-aircraft or fighter defense worth mentioning for the city. As everywhere, factories in Nordhausen had been converted to armaments production.

The Dora concentration camp in Nordhausen produced beginning of April 1945 no V-weapons and other military equipment more. The workers there, including thousands of inmates from the Mittelbau concentration camp and forced laborers , were evacuated. The plant itself or its transport links were never the target of Allied air raids.

The former Luftnachrichtenschule 1 or Boelcke-Kaserne has not been used for military purposes since autumn 1943. Since then it has taken in thousands of workers, and later refugees. In the southern part, Junkers set up an aircraft engine assembly facility called “Nordwerke”, which was mostly operated by “foreign workers”. Since January 8, 1945, there was a soon overcrowded prisoner hospital of the Mittelbau concentration camp in the barracks complex in the northern part. In February, 3,500 prisoners from the Groß Rosen concentration camp in Silesia were added at times .

Previous air strikes

The first air raid alarm in the city was given on September 4, 1940 at night. On August 26, 1940, the airfield was attacked for the first time by two bombers. Other attacks in the vicinity of the city, probably "emergency drops" of bombs, took place from summer 1942 onwards.

On April 11, 1944, an attack with on-board cannons and machine guns resulted in the “first deaths in our city,” noted the Nordhausen aerial warfare writer Johanna Meyer. On August 24, 1944, six Air Force soldiers were killed in one of the increasingly frequent attacks on the air base. The 34 planes attacking with explosive and incendiary bombs also attacked the station. On September 13, 1944, a German fighter plane crashed a flying fortress B-17 near Nordhausen by ramming it. On October 7, 1944, 24 American “flying forts” dropped 57 tons of bombs on the airfield.

From autumn 1944 fighter-bombers began to attack railroad trains in the wider area around Nordhausen. For example, on February 21, 1945, fighter-bombers destroyed a fully occupied express train between Berga-Kelbra and Aumühle by fire from on-board weapons , 40 people were dead on the spot. Attacks by low-level planes resulted in civilian deaths at Nordhausen increasing more frequently.

On February 22, 1945, 30 heavy American B-24 Liberator bombers , whose target is said to have been the marshalling yard, wreaked havoc in the eastern Lower City, on residential buildings and on company premises. The attack took place as part of the Anglo-American Operation Clarion against traffic targets in Germany. For 48 of the 51 dead, a public memorial service took place in the New Cemetery on Schlageter-Ring.

On April 1, 1945, Easter Sunday, a US fighter-bomber hit the "Hessischer Hof" hotel and a neighboring house. He killed 30 civilians and naval officers.

The number of air alarms in Nordhausen had risen to 861 by the beginning of April 1945, 174 of them in March alone, 5 to 6 daily. A main route of the increasing Allied bomber streams led via Nordhausen to Berlin and the central German industrial area. This explains most of the many airborne alarms that kept the population unsteady day and night.

Preparations for the "double strike" and order to attack

As early as the end of 1944, British long-range reconnaissance aircraft carefully photographed the city and its surroundings from the air under daylight illumination from magnesium bombs. At the end of March 1945, the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) gave the decision to destroy Nordhausen to the Bomber Command of the Royal Air Force . This, led by Air Marshal Arthur Harris , issued the immediate order on April 2 for a double strike over two days. 3,466 British soldiers were to take part in the attacks as flight personnel. The target of the attack was declared to them: “ To kill military and Nazi personnel evacuated from Berlin to these barracks ” (meaning the area of the Boelcke barracks and the city of Nordhausen).

The major attack on April 3, 1945

256 bombers of the No. 1 and No. 8 RAF Group , including 247 heavy, four-engine Avro Lancasters (carrying capacity 6 tons of bombs each) and 9 high-speed Mosquito light bombers (each one ton bomb load) took off from England on April 3, 1945. A Polish squadron with 14 machines was also involved. The bombers were accompanied by 17 escort fighter squadrons. 220 bombers reached their destination Nordhausen, casting 16:15 to 16:25 2,690 bombs from. The planes were flying relatively low, the north houses could see the opening of the bomb shafts. This was preceded by the setting of target markings above the Boelcke barracks with illuminated magnesium signs ( "Christmas trees" ) by guiding machines. The main strike was a bunch of 191 Lancaster bombers, which flew in from Kyffhäuser . After many false throws in the area between Bielen and Nordhausen, they particularly destroyed the entire south-eastern quadrant of the city. The main goal was the Boelcke barracks (which were mainly occupied by sick prisoners). The war diary of the British Bomber Command writes: "... to attack what were believed to be military barracks near Nordhausen. Unfortunately, the barracks housed a large number of concentration camp prisoners and forced workers ... The bombing was accurate and many people in the camp were killed; the exact number is not known. " Some of the survivors fled into the area. Due to the destruction of the infrastructure, the city was without electricity, without sirens, and without tap water. The roofs were covered, the windows splintered. “The city was badly hit, but it was still an organized community.” The injured were collected and taken to Neustadt and Sülzhayn ; those who had been bombed out were given emergency quarters in the city itself and its surroundings. Many northern houses fled the city. Two tunnels in the subterranean facilities of Mittelbau Dora in Kohnstein already took in refugees on April 3, later it increased to 10,000. The city hospital was damaged, the patients were taken to emergency hospitals in the neighboring Petersdorf , especially in the Harzrigi excursion restaurant. Bombs also fell on several neighboring villages and their corridors, Bielen was particularly affected. Two bombers were lost on return flights.

The major attack on April 4, 1945

252 bombers of No. 5 Bomber Group took off from England that morning, 243 Lancasters and 9 Mosquitos. 236 machines reached their destination in Nordhausen and carried out the attack. From 09:08 to 09:24 (other information: 09:15 to 09:21), a section of 93 Lancasters targeted 1,039 explosive bombs again on the “Boelcke barracks” region and the main unit dropped 2,784 explosive bombs in rows on the city off, plus incendiary bombs and phosphor containers. The targets had been shown exactly by four marker bombs with light cascades visible from afar. The bomb carpets hit the region of the Boelcke barracks again and destroyed almost the entire old town; only the northern, western and southern peripheral districts remained. The mine bombs also destroyed public air raid shelters, for example one bomb broke through the vaults of the basement of the bowling club house, killing 78 people there. Churches also offered no protection: many parishioners who had fled to the Petrikirche died from the bombs. The bombs almost exclusively hit civilian targets, including all hospitals and military hospitals. The railway systems were preserved, the Halle - Nordhausen - Kassel line was still passable, and military installations were hardly hit, not even a gasoline store filled with 5 million liters. On the other hand, the fires ignited by thrown incendiary material quickly spread to a devastating conflagration that led to a firestorm in the shattered city center, consisting mainly of half-timbered buildings , with its roofs covered since the day before . According to Walter Geiger, it was not a firestorm in the true sense of the word, but rather “a major fire that was not entirely closed in itself”, which, however, played its intended role and contributed to an increase in human losses. Low-flying aircraft disabled attempted fire-fighting and rescue operations. The local fire brigade, if still available, was completely overwhelmed by the situation. Panic reigned among the surviving population, tens of thousands of them fled the inferno of the city. It was also shot at by fighter bombers outside of Nordhausen. Many wounded were brought to Petersdorf, Buchholz and Neustadt using ambulances from the area . Whenever possible, courageous people saved parts of the city. That was the case in the less affected cathedral district northwest of the center and in Altendorf. In this way, the Nordhausen Cathedral , the roof of which was on fire, could be saved from complete destruction. The Kassel fire brigade helped out here, and Wehrmacht pioneers blew up a fire alley. A district was preserved, bounded by the western and northern city walls, the Barfüßerkirche, Kalte Gasse and Königshof and the Altendorf district. In the evening and at night, the city was a sea of flames that shone terribly from afar. In the middle of it, the church tower of St. Petri showed itself as a huge torch, which collapsed around midnight and fell on the nave. RAF pilots who returned from a mission near Merseburg reported at 11 p.m. of “ good fires at Nordhausen ”. The air base was not bombed.

A Lancaster was lost in this attack. The bomb-laden heavy bomber exploded in formation over the city, killing the seven-man crew.

During the two attacks on April 3 and 4, 1945, the RAF dropped a total of 2,386 tons of bombs over Nordhausen.

The situation after the two attacks

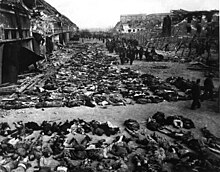

The British Bomber Command reported, as a result of the two major attacks, that "the city was almost completely destroyed, including the barracks blocks". The situation for the population after the attacks can only be described with the term “inferno”. The city center could not be entered for days. Numerous fires were still raging, and the heaps of rubble radiated unbearable heat. Bombs with time fuses went off. The smell of corpses soon lay over the rubble fields, especially in the area of the Boelcke barracks. On the nights of April 6th and 7th, the sick and wounded from Nordhausen and the surrounding area were brought to safety in the Kohnstein by all available vehicles, especially with farmers' carts . According to estimates, the Nordhausen population was distributed as follows on April 7th: 6,000 (8,800) victims dead under the rubble, 6,000 survivors still in the city, 10,000 in the Kohnstein and 20,000 in the surrounding villages, especially northeast of the city.

Together with the air raid on Sondershausen , eleven bombers of the 9th US Air Force launched an attack on Nordhausen on April 8, 1945 at around 6:00 p.m. Due to the heavy smoke development over Sondershausen, they had not been able to locate their actual target due to previous bombs.

On April 10, US tanks approached the south of the city of Nordhausen from the direction of Hain and took it under fire, including the rubble of the Boelcke barracks.

American occupation

On April 11, troops from the 3rd US Armored Division , coming from the south and west, occupied the city without a fight until late afternoon . Buildings that were still habitable had to be cleared by the German population and were occupied by the Americans. Brigadier General Truman E. Boudinot made a series of orders under the impression of the gruesome pictures in the bombed-out Boelcke barracks littered with prisoner corpses. No food shipments have been allowed into the city for the time being. Nordhausen was released for one week for looting by former prisoners and “members of the nations fighting against Germany”. The looters often set fires, which resulted in further losses of habitable buildings. The male population had to transport the surviving, wounded and sick prisoners from the Boelcke barracks to auxiliary hospitals and the almost 1,300 dead from this facility to a special cemetery on Schlageter-Ring. There, on May 13th, with a speech by Mayor Flagmeyer, a memorial service for the dead prisoners took place, to which the occupying forces ordered all male 16- to 65-year-old Nordhäuser. They then received their personal identification on the spot, which entitles them to purchase food cards. In the next few days, the female population of Nordhausen had to come to the graves with bouquets of flowers and then received their personal identification. The looting in the city, in which Germans also participated, went on for weeks. On May 8, the mayor threatened by order of the military government: "I point out that the death penalty can be imposed for looting." The attacks were carried out in German and Polish.

Sacrifice numbers and burial places

On June 17, 1945, the Nordhausen Antifa Committee estimated that over 10,000 people had died in the bombing raids. In 1948, the Nordhausen magistrate put the number of people lost as a result of the bombing raids (in what was then the urban area, excluding the villages that were later incorporated, including Salza ) as follows: 8,800 deaths in total, 6,000 of them from the permanent residents of Nordhausen, 1,500 from the non-permanent population (air war evacuees, Refugees, soldiers, prisoners of war and foreign workers) and 1,300 prisoners from the former Boelcke barracks. Of the 6,000 dead from the permanent population of Nordhausen, 4,000 were women and children, including 4,500 women and children, including the non-permanent residents. Even years later, the remains of hundreds of people were found in the rubble fields of the city. The firestorm has also left its victims without a trace, ashes and shriveled corpses. “It can be safely assumed that the actual number of victims was far greater [than the official 8,800]. Nobody counted them. "

In the first few days, the Americans had bodies lying in the streets taken to the special cemetery on Schlageter-Ring. Others were buried on the spot in bomb craters or fragmentation trenches. A considerable number of civilian victims and German soldiers were then buried in mass graves in the higher part of today's Ehrenfriedhof , not far from the killed prisoners from the Boelcke barracks. Mass graves were laid in the front part of the old main cemetery on Leimbacher Strasse for the victims who were later found without an attachment. Today there is an apartment block at this point. In the first few weeks and months, 920 bomb victims were buried in the new main cemetery on the Ring, in the eastern part near the present red granite monument.

Material and cultural losses

Three quarters of the fortified old town, the new town and the area around the Frauenbergkirche were destroyed. Of 14,300 apartments in 1944, 6,200 were completely destroyed after the attacks, 4,600 were badly damaged and 1,200 were slightly damaged. Only 2,300 apartments were undamaged. The degree of destruction was 74%. 64% of the structural industrial capacity had been destroyed. The urban infrastructure (tram, power grid, gas and water supply) was no longer available or was in a catastrophic condition.

The important cultural buildings and public buildings were irretrievably lost in the hail of bombs and firestorms: the giant house on Lutherplatz, the Rosenthalhaus on the market, the Töpfertor school on Töpferstraße, the Mathilden-Mittelschule in Predigerstraße, the secondary school on Taschenberg, the commercial vocational school the promenade, the city hospital on Taschenberg, the Frauenbergkloster in Martinstraße, the Ilfelder Hof on horse market / Hagen, the old Latin school on Jacobikirchplatz, the Jacobi rectory and the club house in Baltzerstraße. The old town hall , the town hall and the theater were destroyed but rebuilt. Most of the bourgeois half-timbered houses from the 13th to 19th centuries, which are so typical for Nordhausen, have been lost, buildings from Gothic to early Classicism.

None of the seven church buildings in the north remained intact. Four were completely destroyed: the St. Jacobi Church in the Neustadt, the St. Nicolai Church on the market, the St. Petri Church and the Frauenberg Church . Two churches were badly damaged: St. Blasii Church and the Cathedral of the Holy Cross . The Altendorf church of St. Maria im Tale was less affected . K. Bornträger drew the destroyed churches in Nordhausen.

Many of the rescued buildings in the old town were more severely damaged. For many years there was a lack of strength and resources for proper repair and maintenance of value. So what was still worth preserving was lost: entire parts of the medieval city fortifications, the Jewish towers, baroque town houses in the Bäcker- and Pfaffengasse.

Tombs in the lower part of the main cemetery were also hit by bombs.

Pictures of destruction

Impressive photos can be found on Google by entering "Nordhausen Pictures of Destruction" . Below the extensive photo gallery are also illustrated online newspaper articles: "Pictures of the horror" (nnz-online), "Nordhausen after the destruction" (nnz-online), "The hell of Nordhausen" (Thuringian general web reports), "Hail of bombs on Nordhausen "(TLZ).

Licensing difficulties explain why no photos of the destruction are shown in this Wikipedia article.

Explosive contaminated sites

A total of 2,386 tons were dropped by the British Bomber Command and 296 tons by the American Eighth Air Force on Nordhausen. One of the longest lasting effects of the air strikes on the citizens of the city remained hundreds of duds of all sizes: between the rubble of the city and in the soil of the streets, gardens and fields. In the first few years the fireworkers Jochen Nebel and Albin Diebler made a great contribution to defusing found bombs, and from 1962 onwards Helmut Zinke - therefore made an honorary citizen . In the city area, around 100 bombs were defused from 1948 to 1953, then 248 duds were detonated and cleared from 1954 to 1999.

In 1996 a 250-kilogram dud had to be blown up . In 2008 a £ 500 bomb was found in the old town, near the town hall. In 2010 a five-hundredweight bomb was discovered on Taschenberg and 4,500 people were evacuated . These two bombs could be defused. On June 8, 2016, two incorporated villages with a total of 1,080 inhabitants had to be completely evacuated for the controlled detonation of a 1-tonne bomb: Leimbach and Steigerthal . On Sunday, November 4, 2018, 5,300 northern houses were evacuated, including residents of old people's and nursing homes: two "World War II bombs" each containing 227 kg of explosives had to be defused. More than 350 firefighters and other personnel were on duty. Only 3 weeks earlier, two duds had been rendered harmless, also with evacuations. On November 6, 2019, 15,000 people had to be evacuated from the city center (one kilometer radius) overnight after a five-hundredweight explosive bomb was found next to the city theater. It was the largest evacuation operation in Nordhausen after the Second World War.

Experts estimate (in 2020) that around 600 duds are still undetected in the Nordhausen soil

There is a regulation in Nordhausen, according to which every citizen who wants to build must ensure that there are no dangerous goods under their land.

Tombs and monuments

"To a certain extent, the entire city area represents the authentic location of the memory of the air war in Nordhausen."

- Memorial for the victims of the bombing in front of the old town hall : In 1950 a large memorial with a flame bowl was erected on the base of the former Luther memorial at the town hall. It bore the inscription: “4.4. 1945. Destruction of Nordhausen by American bombers - 8,800 victims accuse “( American bombers were wrong, the 3rd April was missing). In 1969 this monument was replaced by a column that still exists today. Jürgen von Woyski's stele, made of light sandstone, depicts childlike bodies stretching upwards, surrounded by flames, and above a dove of peace. The base plate bears the inscription: “Us as a reminder. In memory of the 8,800 victims of the British air raids on 3rd and 4th April 1945 ”. In 1969 the inscription read: “… of the Anglo-American attack on April 3rd and 4th. 1945 ", 2003 then" ... the British air raid "and from 2004 historically correct" ... the British air raids on 3rd and 4th April 1945 ". The annual official commemorative events of the city of Nordhausen take place at this memorial on April 4th.

- In the cemetery of honor west of the Stresemann-Ring there is a memorial, redesigned in 1999, in memory of the more than 1,600 concentration camp prisoners buried here in mass graves, most of them victims of the air raids on the Boelcke barracks on April 3rd and 4th, 1945. Many too Nordhausen civilian bomb victims and soldiers were buried in mass graves in the northern part of the special cemetery, the current cemetery of honor, above the monument. At the time of the Soviet occupation zone and the GDR, the facility was initially called the "Cemetery of Honor for the Victims of Fascism", then in 1979 it was given the addition "... (air raid 1945)" in the official monument declaration. A redesign of the facility planned for 1995, which would also have included the Nordhausen bomb victims and Wehrmacht soldiers under two high crosses, was prevented by an objection by the former prisoners' Euro Committee.

- In the main cemetery (east of the crematorium, almost on the edge of the cemetery) there has been a memorial made of dark red marble since the early 1990s (comes from a memorial for Emperor Friedrich III), the bronze plate of which bears the summary inscription: “In memory of the fallen and Missing people from both world wars, the dead in the bombing raids, the victims of all tyranny. The citizens of the city of Nordhausen ”. To the left of the memorial, in front of the border fence, a large number of bomb victims were buried in communal graves. There are still some simple, large crosses that probably indicate this. On a large area in front of the marble monument, there are grave fields with mostly stone crosses marked by name with Wehrmacht (air force) and civilian war victims from Nordhausen. But there are also inscriptions such as: "Unknown women, unknown child, 26 unknown bomb victims". The annual commemoration of the German War Graves Commission takes place in front of the marble monument .

- Community graves (no longer recognizable) in the south-western part of the old cemetery (on Leimbacher Straße), above a natural stone with a metal plaque and text: “In memory of over 600 victims of the bombing of the city of Nordhausen on 3rd / 4th. April 1945, who were buried in this place ”(historically correct it should read“ the bombing raids ”and“ on April 3rd and 4th ”). During the GDR era, a block of flats was built on Leimbacher Strasse on part of the cemetery.

- The St. Petri Tower on the Petersberg burned down in the bombing, lost its top and its nave. Until 1987 it was widely recognizable as a blunt aerial warfare ruin, then it was given a tower helmet again. The tower has been designed as an aerial war memorial since 1990. A “room of calm” calls to mind the more than 100 people who sought refuge here and were buried under the rubble of the nave. The bones found were reburied in the main cemetery. The location of the earlier nave has been marked.

- Another memorial (from 2005) on the Petersberg, not far from the tower: A seated stone sculpture of a man who has bowed his head in mourning. Inscription: “In memory of the dead in the bombing raids of April 3rd and 4th 1945 on Petersberg”.

- The Frauenberg church , of which only a rebuilt transept and choir exist after the bombing, is also an aerial war memorial. At the end of a crossroad in 1995 on the 50th anniversary of the destruction, a seven meter high wooden cross was placed on the facade of the church, later on the window attached to the former nave. It bears the inscription: “Blessed are those who make peace - 3./4. April 1945 Destruction of Nordhausen - Erected by the town's parishes on April 2, 1995 as a symbol of Christian hope ”.

literature

- Manfred Bornemann: Fateful days in the Harz. What happened in April 1945 . Piepersche Druckerei und Verlag, 14th edition 2002, OCLC 722983936 .

- Fred Dittmann: Nordhausen Air Base and Air Communication School 1935–1945 . Rockstuhl Verlag, Bad Langensalza 2006, ISBN 3-938997-42-7 .

- Walter Geiger: Nordhausen in the bomb sight - On the air war fate of a central German city 1940–1945 . Neukirchner Verlag, Nordhausen 2000, ISBN 3-929767-43-0 .

- Olaf Groehler : bombing war against Germany . Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-05-000612-9 .

- Peter Kuhlbrodt , Nordhausen City Archives (ed.): Fateful year 1945 - Inferno Nordhausen. Chronicle, documents, experience report . Archive of the city of Nordhausen, 1995. ISBN 3-929767-09-0 .

- Martin Middlebrook and Chris Everitt: The Bomber Command War Diary. An Operational Reference Book 1939-1945 . Midland. 2011. ISBN 978-1-85780-335-8

- Jürgen Möller: The fight for the Harz. April 1945 . Rockstuhl-Verlag, Bad Langensalza, 2nd edition 2013, ISBN 978-3-86777-257-0 .

- Manfred Schröter: The destruction of Nordhausen and the end of the war in the Grafschaft Hohenstein district in 1945 . Contributions to local history from the city and district of Nordhausen, Meyenburg-Museum Nordhausen, 1988, OCLC 165647954 .

- Martin Clemens Winter: Public memories of the aerial warfare in Nordhausen, 1945–2005 . Tectum Verlag, Marburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-8288-2221-4 .

- Rudolf Zießler : Nordhausen , district of Erfurt, in: Fates of German Monuments in World War II , Volume 2. Ed. Götz Eckardt, Henschel-Verlag, Berlin 1978, OCLC 313412676 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Olaf Groehler: Bomb war against Germany . Berlin 1990. p. 449

- ↑ Peter Kuhlbrodt (Ed.): Fateful year 1945. Inferno Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1995. pp. 20, 33

- ↑ Manfred Schröter: The Destruction of Nordhausen . Meyenburg-Museum Nordhausen, 1988, pp. 6-8

- ^ Walter Geiger: Nordhausen in the bomber sight . Verlag Neukirchner, Nordhausen 2000. p. 258

- ^ Walter Geiger: Nordhausen in the bomber sight . Nordhausen 2000, p. 220

- ↑ Fred Dittmann: Air Base and Air News School 1 Nordhausen 1935-1945 . Bad Langensalza, 2006, p. 141

- ↑ Peter Kuhlbrodt: Fateful year 1945. Inferno Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1995, pp. 17-18

- ^ Walter Geiger: Nordhausen in the bomber sight . Nordhausen, 2000, p. 100

- ↑ Manfred Schröter: The Destruction of Nordhausen . Meyenburg-Museum Nordhausen, 1988, pp. 8-17

- ^ Walter Geiger: Nordhausen in the bomber sight . Nordhausen, 2000, p. 57

- ↑ Manfred Schröter: The Destruction of Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1988, p. 55

- ↑ Manfred Schröter: The Destruction of Nordhausen . Meyenburg-Museum Nordhausen, 1988, pp. 54-55

- ^ Walter Geiger: Nordhausen in the bomber sight . Nordhausen 2000, pp. 108-109

- ^ Walter Geiger: Nordhausen in the bomb sight . Nordhausen 2000, p. 121

- ^ Walter Geiger: Nordhausen in the bomber sight . Nordhausen 2000, p. 121

- ^ Walter Geiger: Nordhausen in the bomber sight . Nordhausen, 2000. p. 149

- ↑ Manfred Schröter: The Destruction of Nordhausen . Meyenburg-Museum Nordhausen, 1988, pp. 49, 54

- ↑ Martin Middlebrook and Chris Everitt: The Bomber Command War Diaries . Midland. 2011. pp. 691/692

- ↑ Manfred Schröter: The Destruction of Nordhausen . Meyenburg-Museum Nordhausen, 1988, p. 22 f.

- ↑ Martin Middlebrook and Chris Everitt: The Bomber Command War Diaries . Midland. 2011. p. 691

- ^ Walter Geiger: Nordhausen in the bomber sight. Nordhausen 2000, pp. 147, 149

- ↑ Peter Kuhlbrodt: Fateful year 1945. Inferno Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1995, p. 23

- ↑ Manfred Schröter: The Destruction of Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1988, p. 61

- ^ Walter Geiger: Nordhausen in the bomb sight . Nordhausen 2000, pp. 169, 179-181

- ↑ Manfred Schröter: The Destruction of Nordhausen . Meyenburg-Museum Nordhausen, 1988, p. 26

- ↑ Peter Kuhlbrodt: Fateful year 1945. Inferno Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1995. Eyewitness reports

- ^ Rudolf Zießler: Nordhausen , district of Erfurt. In: Fate of German Monuments in the Second World War . Edited by Götz Eckardt. Henschel-Verlag, Berlin 1978. Volume 2, pp. 488-489

- ↑ Peter Kuhlbrodt: Fateful year 1945. Inferno Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1995, p. 23

- ^ Walter Geiger: Nordhausen in the bomber sight . Nordhausen 2000, p. 180 f.

- ↑ Fred Dittmann: Air Base and Air Communication School 1 Nordhausen 1935-1945 . Bad Langensalza 2006, p.?

- ↑ Manfred Schröter: The Destruction of Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1988, p. 57

- ^ Olaf Groehler: Bomb war against Germany . Berlin 1990, p. 449

- ^ Walter Geiger: Nordhausen in the bomber sight . Nordhausen 2000, p. 154

- ↑ Peter Kulhlbrodt: fateful year 1945. Inferno Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1995, p. 24

- ↑ Manfred Schröter: The Destruction of Nordhausen . Meyenburg-Museum Nordhausen, 1988, p. 30

- ↑ Thomas Blumenthal: Anatomy of an attack. The bombing of the city of Sondershausen on April 8, 1945 . Diploma thesis, University of the Federal Armed Forces, Munich 2002, pp. 82, 84

- ↑ Manfred Schröter: The Destruction of Nordhausen . Meyenburg-Museum Nordhausen, 1988, p. 37

- ↑ Manfred Schröter: The Destruction of Nordhausen . Meyenburg-Museum Nordhausen, 1988, p. 49

- ↑ Peter Kuhlbrodt: Fateful year 1945. Inferno Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1995, p. 177

- ↑ Manfred Schröter: The Destruction of Nordhausen . Meyenburg-Museum Nordhausen, 1988, p. 50

- ↑ Peter Kuhlbrodt: Fateful year 1945. Inferno Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1995, pp. 48, 63

- ↑ Peter Kuhlbrodt: Fateful year 1945. Inferno Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1995, p. 62

- ↑ Peter Kuhlbrodt: Fateful year 1945. Inferno Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1995, p. 115

- ↑ Peter Kuhlbrodt: Fateful year 1945. Inferno Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1995, p. 126

- ^ Walter Geiger: Nordhausen in the bomber sight . Nordhausen, 2000. p. 187

- ↑ Manfred Schröter: The Destruction of Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1988, p. 59

- ↑ Manfred Schröter: The Destruction of Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1988, pp. 59-60

- ↑ Manfred Schröter: The Destruction of Nordhausen . Meyenburg-Museum Nordhausen, 1988, p. 60

- ↑ Manfred Schröter: The Destruction of Nordhausen . Meyenburg-Museum Nordhausen, pp. 60–62

- ^ Rudolf Zießler: Nordhausen . In: Fate of German Monuments in the Second World War . Edited by Götz Eckardt. Henschel-Verlag, Berlin 1978, Volume 2, pp. 494-495

- ^ Walter Geiger: Nordhausen in the bomber sight . Nordhausen 2000, pp. 303-305

- ↑ Nordhausen. Counselor for bereavement. Nordhausen 2008

- ^ Olaf Groehler: Bomb war against Germany . Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1990, p. 449

- ^ Walter Geiger: Nordhausen in the bomber sight . Nordhausen 2000, p. 263 f.

- ↑ Silvana Tismer and Hans-Peter Blum: Bomb explosion successfully completed with a delay . Thüringische Landeszeitung, June 9, 2016. P. 9

- ↑ Bombs successfully defused. Thousands of people evacuated in Nordhausen . Thuringian State Newspaper, November 5, 2018

- ↑ 15,000 people evacuated after a bomb was found . Thuringian newspaper, November 7, 2019

- ↑ MDR November 8, 2019

- ↑ Gerald Müller: Precision work. Andreas West has been the responsible demolition manager in Thuringia for 15 years . Thuringian newspaper, June 27, 2020

- ↑ Katja Dörn: The danger is rusting in the Thuringian soil . Thuringian newspaper, December 12, 2014

- ↑ Martin Clemens Winter: Public memories of the aerial warfare in Nordhausen 1945-2005 . Tectum Verlag, Marburg 2010, p. 111

- ^ Martin Clemens Winter: Public memories of the aerial warfare in Nordhausen 1945-2005 . Marburg 2010, pp. 115-118

- ↑ Manfred Schröter: The Destruction of Nordhausen . Meyenburg-Museum Nordhausen, 1988, p. 59

- ^ Martin Clemens Winter: Public memories of the aerial warfare in Nordhausen 1945-2005 . Marburg 2010, p. 114

- ↑ Manfred Schröter: The Destruction of Nordhausen . Meyenburg-Museum Nordhausen, 1988, pp. 59-60

- ↑ Manfred Schröter: The Destruction of Nordhausen . Nordhausen 1988, p. 59

- ↑ Martin Clemens Winter: Public memories of the aerial warfare in Nordhausen 1945-2005 . Marburg 2010, p. 125