Kinderland delivery

Before the Second World War, the term Kinderlandverschickung (KLV) was used exclusively for the recreational deportation of children. Today, this keyword is mostly used to refer to the extended Kinderlandverschickung , in which, from October 1940, schoolchildren and mothers with small children from German cities threatened by the air war were placed in less endangered areas for a longer period of time. The "Reichsdienststelle KLV" evacuated a total of probably more than 2,000,000 children by the end of the war and probably looked after 850,000 schoolchildren between the ages of 10 and 14, as well as older ones in KLV camps. There are numerous and detailed reports from contemporary witnesses about life in "KLV camps". Reports of “mother and child deportation”, of being placed in foster families or with relatives in “air-safe areas” are rare. The research literature on evacuation measures with the designation "Extended Kinderlandverschickung" was still incomplete in 2004, particularly with regard to the psychological consequences of the war.

Kinderland sending as social welfare

As early as the end of the 19th century, needy and health-endangered city children were sent to the countryside for recreational stays in foster homes. Even then, the term "Kinderlandverschickung" appeared in some regions. From 1916 onwards, a “Reich Central Office for Urban Children” coordinated holiday stays lasting several weeks. In 1923 488,000 children were sent. By the aid agency Mother and children of the National Socialist People's Welfare (NSV) such Kinderlandverschickungen were, for example, from 1933 in Würzburg carried out, especially children from the premises Dusseldorf, Cologne and Saarland came to Lower Franconia. From 1934 onwards, around 650,000 children up to the age of 14 took part in what is now generally known as the “Kinderlandverschickung”. Such recovery expeditions, which usually lasted no longer than three weeks, continued to be offered to a lesser extent during the Second World War . As of May 1933, the NSV, as a newly founded association, acted as a state organ alongside some remaining welfare organizations in welfare and youth welfare as well as public health. From 1940, she organized the Kinderlandverschickung for children under ten years.

Extended children's area dispatch

When preparations were made to evacuate school children from "air-endangered areas", they fell back on the experiences they had made during the recovery deportation. The sources do not provide any information about who developed and promoted the plans for an evacuation operation. It can be proven that Adolf Hitler himself intervened and triggered the action. At this point it became clear that the British government was not ready to surrender and - as a first heavy air raid on September 24, 1940 showed - even Berlin was reached by Royal Air Force bombers .

For the most part, when the keyword “Extended Kinderlandverschickung” is used, the evacuation of ten to fourteen year old schoolchildren is thought of. The Hitler Youth (HJ) was responsible for this in terms of organization and personnel . The students lived - often together with their classmates - separated from their families for several months and spent an important phase of their development in a KLV camp.

However, three other evacuation campaigns that covered a larger group of people were also carried out under the same name. The National Socialist People's Welfare Association (NSV) was responsible for a "mother-and-child deportation", in which mothers with small children and older siblings were taken in with host families in safe areas. Also organized by the NSV and financed by the state was an action in which a large number of primary school children up to the age of ten were placed in “foster families”. Long-term private “sending to relatives” was also encouraged for children of all ages; The NSV provided transportation and paid the travel expenses.

Introduction of the extended KLV

On September 27, 1940, Reichsleiter Martin Bormann wrote in a confidential circular:

“By order of the Führer , children from areas that repeatedly have nocturnal air alarms , initially especially from Hamburg and Berlin, are sent to the other areas of the Reich on the basis of the free resolution of their parents or guardians . The Fiihrer has commissioned Reichsleiter Baldur von Schirach to carry out these measures [...] The NSV is responsible for the deportation of the children who are not yet of school age and the children of the first four school years; the HJ takes over the accommodation from the 5th school year on. The placement campaign begins on Thursday, October 3, 1940. "

The term " evacuation " was avoided; The only euphemisms that were spoken of was “accommodation campaign” and later “extended children's area dispatch”. The population, however, saw through this veiled language regulation. The secret situation reports of the security service of the SS , the so-called reports from the Reich , stated in summary that there was talk in the population of the "evacuation of large cities threatened by air" and a "camouflaged forced evacuation". The leadership expects "apparently still very heavy blows". Overall, the rumors would have produced an "extremely detrimental psychosis ". Martin Bormann then stated on behalf of Hitler that no more violent air attacks were to be expected. Children from arboreal colonies who would have to seek protection at night in unheated air raid shelters or distant bunkers should be sent on a voluntary basis .

A little later cities such as Dortmund, Essen, Cologne and Düsseldorf were included in the program, and children from Schleswig-Holstein, Lower Saxony and Westphalia were also brought to safety in Bavaria, Saxony and East Prussia . It is estimated that up to 300,000 children had been evacuated by early 1941; more than half of them were in one of around 2,000 KLV camps.

Organization and reception areas

The "Reichsdienststelle Kinderlandverschickung", an office of the Reich Youth Leadership in Berlin , had the highest responsibility . Baldur von Schirach appointed Helmut Möckel as director, who held office until 1943. The presentations “Leadership” and (political) “Orientation” were given by Gerhard Dabel , who in 1981 published an annotated documentation on the KLV camps and thus established a lasting positive point of view.

According to the usual polycratic organizational structure of National Socialist institutions, the areas of competence overlapped: In addition to the Hitler Youth with the Reich Youth Leadership, the Reich Ministry for Science, Education and National Education with Bernhard Rust at the head, the National Socialist People's Welfare (NSV) under Erich Hilgenfeldt and, until 1943, the National Socialist Teachers' association with Fritz Wächtler .

For the year 1941, the Bavarian Ostmark , Salzburg , Styria , West Prussia , Pomerania , Silesia as well as the Sudetenland , Slovakia and the Wartheland are listed as receiving areas . Safe countries such as Hungary , the protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia at the time, and Denmark were also destinations for “a selection of young people who were impeccable in terms of posture and performance, so that they would represent the German reputation abroad in a worthy way.” Rural accommodation in the vicinity of endangered large cities was also increasingly used; For 1943, the Mark Brandenburg , Schleswig-Holstein and the Harz for students from Braunschweig are also named as reception areas . This apparently met the wishes of the parents, who preferred to have their children within reach.

KLV warehouse

Selection of participants

Only children who did not suffer from infectious diseases should be admitted to a KLV camp. Epileptics , chronic bed-wetting and "difficult to educate asocial adolescents" were rejected. From 1941 onwards, a school medical examination and a questioning of the teachers took place before departure .

“ Second degree Jewish half-breeds ”, who, according to the implementing provisions of the Nuremberg Laws, were often treated as “ Germans ” and were even able to join the Hitler Youth, were not permitted. This regulation was not repealed until November 1943.

Number of participants

The statistical documents of the Berlin Reichsdienststelle KLV have been destroyed. Numbers up to 1942 can be read from other sources, further numbers of participants can only be reconstructed indirectly using information from the Reich Ministry of Finance or the school authorities. The estimates given in the literature for the number of children housed in KLV camps vary widely and range from 850,000 to 2,800,000. There are many arguments in favor of the lowest value.

The evaluation shows a steep increase in the number of children sent to KLV camps up to the peak in July 1941. In that month, 171,079 pupils were in a camp. By the end of 1941 this number had almost halved. In 1942 there were hardly more than 50,000 children in KLV camps. For the year 1943 an increase in the number of deportations can be assumed, since schools with all classes should now be relocated. For the last two years of the war, regional figures consistently show a downward trend. As a result of his research, Gerhard Kock points out:

"Contrary to the obvious assumption that the parents wanted their children to be in the physical security of the KLV camps, the willingness to participate in the deportation sank as the war went on."

In the last years of the war, many reception areas that had previously offered security from the bombing raids were now also affected by the air war. Outskirts of large cities and nearby communities offered comparable protection. In these uncertain times, many parents did not want to send their child far away, especially since the restricted transport connections hardly allowed regular contact.

Length of stay

The National Socialist leadership expected a victorious end to the war soon and believed that the evacuation could be ended in a few weeks. In fact, it took six months for the first children to return to their parents from the camp. From mid-1941 onwards, parents were advised of upcoming transports that the shipment would take six to nine months and that early retrieval was generally prohibited. If the parents did not expressly object, another KLV camp stay could follow. Especially in the last years of the war, some children spent more than 18 months in the camp without a break.

Leave of absence was tied to certain events such as a father's leave from the front . Going home for Christmas should be avoided; however, this order was apparently not always followed. Visits from parents were initially not officially allowed. Some parents cited this ban as a reason for deciding not to send their child with them. Therefore, from 1943 onwards, “parent visit days” were set up and special trains made available.

Recording capacities

The individual KLV camps, the number of which, according to estimates, increased to around 5,000 during the war years, were very different. There were KLV main camps for the extended children's area dispatching with over 1000 participants and camps with only 18 students. The admission capacities were based on the respective places of accommodation: A KLV camp could be accommodated in a luxury hotel , in a youth hostel , in a monastery , in an unheatable restaurant or in a remote village school without running water. In rare cases there were “open KLV camps” in which students were housed with families and looked after by the local HJ in their free time.

At first, attention was only paid to grouping pupils of the same age in a KLV camp. Later attempts were made to evacuate entire school communities or at least to send complete classes together with their class leader.

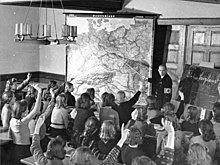

Organization of the camp

The organizational structure of the KLV warehouse was uniform. The camp communities were separated by sex . The camp manager was a teacher who was also responsible for teaching in the camp. For 30 to 45 pupils, the Hitler Youth leadership assigned a warehouse team leader or a warehouse girl leader. These regulated the daily routine from the flag roll call to the tattoo and the Hitler Youth service. As the camp manager, the teacher had the highest authority in all camp matters, but camp life itself was largely determined by the young camp team leader.

The camp team leaders were often high school students aged 17 or 18 who were seconded from their home school for three to four months and prepared for their task in a two-week course. After six weeks of deployment, a two-day follow-up training was planned. The KLV camps were monitored by inspectors, site officers and ban officers from the Hitler Youth leadership.

daily routine

The "Reichsdienststelle KLV" provided the framework for the daily routine. After that, the day began in the summer at 6.30 a.m. with waking, washing, airing the bed, room service and a health roll call. Welcome speech and breakfast followed at 7.30 a.m. Four hours were provided for the lessons. On Sundays a flag roll call and a morning party were on the agenda. After lunch and an hour of rest, a tightly organized program began, which was only interrupted by dinner. Depending on the age group, you should go to sleep between 9:00 p.m. and 9:30 p.m.

The quality of the lessons depended on the number of subject teachers sent along and thus on the size of the camp. At the end of the several months' stay, the teachers issued “certificates of achievement” in which a transfer could be advocated. Instead of vacation and a trip home to the parents, there was a three-week period in the camp without lessons.

The camp as a form of education

The aim of the entire evacuation operation was to dispel the population's concerns about air raids and to protect children and young people from being sent from bombs. As a side effect, mothers who remained behind could now be released for work that was important to the war effort. The camp education, which was supposed to replace an individual education by parents and half-day school , also matched the ideological concept of the National Socialists .

The Reich Minister for Science, Education and Public Education Bernhard Rust declared in 1934 that one would become a National Socialist through “camps and columns”. Rudolf Benze , Ministerialrat in the same ministry, named in 1936 the essential goal of national political “formation education” as the emotionally internalized commandment to subordinate individual needs in favor of a national community . In addition to the communal experience at mass events, torchlight parades and rallies, the training camps of the various NS branches served this goal. The large number of camps was barely manageable: Reich labor service camps , regional year camps , teacher training camps , military training camps , camps for court trainees and university teachers, camps for the resettler youth and community camps for the Hitler Youth. A strictly regulated daily routine, uniforms, pronounced command structures and submission rituals, sport as physical exercise, field exercises, marching columns and symbolic celebrations were important elements of this National Socialist education .

In the official organ of the youth leader of the German Reich in 1943 it was openly stated which possibilities of influence opened up: “The establishment of the KLV camp offers the opportunity to fully educate young people on a large scale and for a longer period of time. School work, Hitler Youth service and leisure time can be equally influenced educationally here. "

Only fragments of the training material for KLV leaders have been preserved as a source. After that, camp education was to be based on order and discipline , command and obedience ; Military jargon was used as a linguistic model. With the aim of inspiring young people and shaping them into unconditional National Socialists, flag roll calls, solemn celebrations, the singing of National Socialist battle songs and group visits to cinema newsreels were instrumentalized. Hardness training, martial arts, field games, marching and shooting served in boys' camps for military training .

Church resistance

As early as February 1941, the secret SD reports spoke of “church counter-propaganda” and rumors: With the free “Extended Kinderland Dispatch,” the state was not concerned with bringing the children to safety, but rather alienating them from their parents and in the camp to create an education without religion. The warning pastoral letter from Bishop Clemens August Graf von Galen that the children in the camps remained without any ecclesiastical or religious care had resulted in a significant decrease in the number of reports about the extended deportation to Kinderland.

Formally, participants in the KLV camp had the opportunity to attend a service on Sundays . Religious instruction was also permitted in some grades according to the current timetable . A National Socialist who was hostile to the Church could easily circumvent these provisions: no teacher was forced to give religious instruction; On Sunday morning, the camp team leader was able to offer an attractive leisure activity.

Resistance from parents

The propaganda emphasized the recreational value, the good nutrition, the undisturbed night sleep, an undisturbed teaching and the community education in the camp as advantages of the KLV . Accommodation was free and relieved the parents' household budget. Nevertheless, sending them to KLV camps met with reservations and even remained “an unpopular measure until the end of the war”. In an SD report from October 25, 1943, i.e. after the devastating air raids on Hamburg , it was stated:

“Despite all the advertising campaigns [...], the overwhelming majority of parents have a strong rejection of being sent to Kinderland when they are separated from their parents. [...] Of the z. About 70,000 schoolchildren present in Hamburg at the moment have agreed to be sent only 1,400. [...] There is a strong tendency to bring the children back to their hometowns everywhere. "

The parents justified their negative attitude with fears that the children would be alienated from them , that years of separation were now expected, that visiting distant areas would be difficult, and that they had also heard of inadequate catering, poor accommodation and treatment.

The principle of voluntariness was not formally restricted. However, this was incompatible with a decree by Schirach of June 15, 1943, which ordered the closed relocation of schools in order not to have to distribute any remaining students to other classes or to teach in collective schools. Parents were increasingly under pressure to explain when they didn't want to send their child along. Local authorities falsely claimed that local schooling was not planned or threatened to withdraw from secondary schools.

Repatriation at the end of the war

Contemporary witnesses report the delayed and hastily carried out liquidations of their KLV camp. Sometimes an orderly repatriation was no longer possible because there was a lack of transport, and sometimes fighting prevented the journey home. In several cases, students had to make their way to their parents on their own or in small groups. The generalizing claim that the organization had completely collapsed by the end of the war and millions of children were trapped in the camps is contested by other historians. In the research literature, this part has so far not been adequately processed. Regional historical sources have only been evaluated in exceptional cases and cannot be easily transferred.

In Hamburg , which was affected by Operation Gomorrah , sharp disputes broke out between those in charge of the school authorities and representatives of the Hitler Youth, who refused to be returned. At least the fourteen-year-olds should march on to other camps when the enemy approached. In this conflict, the school authorities finally prevailed and were able to bring almost all students home from the KLV camps in Schleswig-Holstein and Mecklenburg in good time before the city was handed over without a fight. The orderly repatriation of schoolchildren from 26 KLV camps in the Czech border area and in the Bayreuth district was no longer possible. On May 3, 1945, the administration of the Hamburg KLV was transferred to the youth welfare office, but was soon taken over by the school administration. This was faced with allegations, threats and outbursts of desperation from parents. An early inspection trip resulted in:

“On the whole, the situation was satisfactory except for the Czech border area in the Bohemian Forest , where some of the camps had been expelled or had fled and embarked on the trek . [...] Many closed camps had been loosened up by distributing the children among farmers. […] Unfortunately, some boys had escaped from the camps on their own initiative before or after the enemy occupation and set out on the trampoline route to Hamburg. "

In total, the KLV service center in the school authorities - which was reinstated after a short interlude - brought an estimated 4,000 Hamburg pupils back with their teachers from July to December 1945. The majority of the younger children who were still housed in family care centers stayed with the host families until spring 1946.

Accommodation in families

The National Socialist People's Welfare Association (NSV) was responsible for all children under ten years of age as part of the children's area .

Reliable figures are available up to mid-1942. According to this, around 202,000 mothers with 347,000 children were transported in special trains from the "air-endangered areas". It is estimated that by the end of the war, a total of around 850,000 primary school children had been evacuated. With this figure, however, double counting cannot be ruled out, possibly including children who were housed with relatives for a long time and who used a special NSV train for the journey.

Mother and child deportation

The "mother and child dispatch" was aimed at mothers with small children up to three years of age. This age limit was later raised to six years; older siblings could be taken along. Most of the mothers were housed with host families, who received a state residence allowance and increased food allocation. The offer of mother-and-child deportation was gladly taken up, so the organizers considered a time limit of six months. However, it soon seemed absurd to send the evacuees back to the areas that were increasingly affected by air strikes.

The different lifestyles of townspeople and rural host families made it difficult to live together. There were complaints about insufficient help in the household or in agriculture . The big city dwellers were perceived as too demanding and could supposedly afford everything financially. A contribution to the costs was only required from 1943 onwards from the mothers who were hosted. Such difficulties did not arise in NSV-owned homes, which, however, did not have nearly the necessary places and were reserved for expectant mothers and mothers with babies.

The mother-and-child deportation not only ensured that the children were unaffected by night air raids and that the fathers who were at war could be reassured. The urban living space vacated by the sent families was increasingly being used by war-important companies as alternative quarters for bombed-out skilled workers.

Dispatch to foster families

School-age children between the ages of six and ten were placed in family care centers by the NSV. From 1943 onwards, older students were occasionally taken into foster families . The duration of the dispatch was planned for half a year, but could be extended several times after a home leave. In addition to the ration cards, the host families received a daily contribution of two Reichsmarks from the NSV.

Many parents viewed the sending to foster families as an extended recovery period. The offer was willingly used, especially since initially the belief in a quick " final victory " seemed to hold out the prospect of a short separation period.

The pupils attended the public school at the location where they were taken. If there was not enough capacity, separate classes were set up and instruction was given in shifts; Teachers from the sending area were then seconded there. Difficulties arose when a country school was only run in one or two classes, i.e. children of different grades were taught in one room. There was often resistance from parents who feared that their child would not be able to learn enough there. Therefore, the organizers tried to send children of the same age together to one place so that they could form their own class.

Sent to relatives

Large numbers of children have been privately sent to live with relatives. Often mothers went with them. The NSV put together special trains that did not incur travel costs.

The accommodation with relatives was evidently used actively in the last years of the war. Parents did not have to be opponents of the regime or loyal churchgoers who rejected the ideological influence in the KLV camp to see it as an advantage to know that their child was in good hands with relatives. You could visit your child at will or bring them back at short notice if the situation changed. Apparently, relatives were often only faked to the authorities in order to keep the children with them. Carsten Kressel interprets the bringing together of families with simultaneous rejection of state evacuation offers as an "emancipation process of the population", which should be particularly emphasized in view of the traditional religious belief and power of the party.

So far, there is no reliable information about the extent of these private evacuation measures. The NSV was only able to record those children and adolescents in their statistics for whom they made places available in special transports.

Interpretations

Most of the time witnesses who spent part of their childhood in a KLV camp describe this time as a cheerful and carefree coexistence in a community of peers, only overshadowed by " homesickness ". An intensely experienced comradeship , greater personal responsibility and close ties to the teachers are praised. They would not have felt any political indoctrination , and even in retrospect, this perception, felt at the time, usually condenses into a firmly established judgment.

On the other hand, contemporary witnesses rarely report humiliation and harassment to which they or others were exposed as unsportsmanlike “weaklings”, as churchgoers or inhibited outsiders. Jost Hermand complains of strenuous military sports exercises, constant drill , permanent intrusive indoctrination and the "brutalization in the horde" with a pecking order in which the weaker were ruthlessly put down.

Former functionaries, participating teachers and camp team leaders praise the "extended Kinderlandverschickung" mainly as an "extensive humanitarian and social work", attest to self-sacrifice and a great educational commitment and deny any ideological influence on the young people entrusted to them.

Many former participants in KLV camps confirm this claim and assert that there was no ideological influence in their camp:

“There was almost no political training at all. The main things that were cultivated were: camaraderie and the feeling of togetherness, being there for someone. "

“I don't remember being deliberately trimmed into politics. Maybe it was done so skillfully that we didn't notice it that quickly. [...] We have never known anything else. "

Such judgments will be correct in individual cases, but as a generalization they contradict the declared intentions of the rulers and portray the Hitler Youth leaders, who were enthusiastic about National Socialism, as having no influence. Eva Gehrken points out that contemporary witnesses did not reflect on attitudes, values and norms that conformed to the system even before their camp life would have taken over. Therefore, most of them did not notice an ideological orientation as something extraordinary and only reflected “a subjective view of reality”.

The widespread opinion on Kinderlandverschickung puts the humanitarian aspects in the foreground, emphasizes the care for the lives of the children as well as the willingness of parents and carers to make sacrifices and leads to the judgment: "The KLV was a good deed". It is noted that an estimated 74,000 children were killed in bomb attacks. Surviving children who did not take part in the deportation to Kinderland, which was less affected by the war , are more heavily burdened by the traumatic experiences with long-term effects than KLV children.

However, this positive assessment ignores the fact that the students in the KLV camp were shielded from a Nazi-specific education during a formative phase of life. Kock judges that the KLV did not achieve its goal as an air raid protection measure because those responsible did not manage to win all parents over. If the “Extended Kinderland Dispatch” had had a similar character to the “Relatives Dispatch,” which was only installed in 1943, the action would have brought more children from the cities to safe parts of the Reich and thus been protected from enemy bombs.

Child evacuation in other countries

The other countries hit by the bombing also ran state evacuation programs for children.

United Kingdom

Evacuation measures had already started during the Sudeten crisis in 1938; but the children were immediately brought back. Two days before the outbreak of war, a large-scale evacuation of school children began in the UK . They were sent with their teachers. The government admitted that the air defense measures did not offer reliable protection - unlike in Germany, where it was announced that its own air defense was impenetrable. The quickly organized evacuation also served the unspoken purpose of counteracting an uncontrolled escape movement that would have severely hampered national defense in the event of a feared invasion.

An early demand estimate by the administration amounted to places for four million evacuees; in fact, the number of people evacuated at the same time never exceeded two million. In September 1939, 827,000 schoolchildren and 525,000 mothers and small children were evacuated from threatened cities. If no relatives could offer a place of refuge, they were housed with host families in the countryside. The numbers fluctuated strongly and depended on the actual course of the air war as well as on the general assessment of the risk situation. In August 1940 the number of evacuees had fallen to 438,000 and 64,000 respectively, then rose in February 1941 to 492,000 and 586,000 and, after a significant decrease, reached a high point again in June 1944 when the V2 attacks began.

Unlike in Germany, evacuation in the UK was seen as a temporary protective measure. The possibility of escape offered reassurance and was a voluntary option that was not designed for a longer period and was used flexibly. The host families received compensation, the amount of which was set by the state. Compulsory admissions were possible, but rarely had to be enforced.

Evacuating children overseas was considered and initiated as the Children's Overseas Reception Board . This operation was canceled after a German submarine sank the transport ship City of Benares on September 18, 1940 .

Several welfare state reform projects were developed in England during the war and implemented after the war by the Labor government under Clement Attlee . Until the 1980s, the prevailing thesis was that the first wave of evacuations triggered these plans because it made the social misery of the children from the big city slums drastically visible.

Japan

Due to the increasingly massive American air raids, the government of the Japanese Empire decided in June 1944 to evacuate third to sixth grade students from the big cities. Those who had no relatives in the country were taken to accommodations set up by the state in temples, country inns, and similar places at the request of their legal guardians. In the first phase of the evacuation program, around 360,000 children and their teachers from the 13 urban areas of Tokyo , Yokohama , Kawasaki , Yokosuka , Osaka , Kobe , Amagasaki , Nagoya , Moji , Kokura , Tobata , Wakamatsu and Yahata (the latter five nowadays Kitakyushu ) were in spent over 7000 accommodations. In March 1945 the program was expanded to include younger children.

The state budget for the evacuation program was 100 million yen in 1944 and increased to 140 million in 1945. However, these amounts were insufficient to support and shelter so many children. Parents were expected to support their children financially or with food. In addition, many of the children had to work for their hosts.

literature

- Renate Bandur: Meine KLV-Lagerzeit In: Documents and reports on the extended Kinderlandverschickung 1940-1945 , volume 3, project, Bochum 2004, ISBN 3-89733-120-9 .

- Heinz Boberach : Youth under Hitler . Droste, Düsseldorf 1982, ISBN 3-8112-0660-5 (a report objectified from archive documents, including about the KLV), further edition: Gondrom, 1993.

- Georg Braumann: Evangelical Church and Extended Kinderlandverschickung In: Documents and reports on Extended Kinderlandverschickung 1940-1945 , Volume 2, Project, Bochum 2004, ISBN 3-89733-119-5 .

- Gerhard Dabel (Hrsg.): KLV - The expanded children's country dispatch. KLV camp 1940–1945. Documentation about the "greatest sociological experiment of all time". Schillinger, Freiburg 1981, ISBN 3-921340-60-8 (on reliability Kock, p. 19 ff. / Gehrken, p. 149 ff.)

- Eva Gehrken: National Socialist upbringing in the camps of the extended Kinderlandverschickung 1940–1945. Research center for school history and regional school development, Gifhorn 1997 (also dissertation at the Technical University of Braunschweig , 1996).

- Markus Holzweber: "Recreation in the midst of the war in 1941" - memories of a city child from Hanover of the stay in Langschlag as part of the Kinderlandverschickung (KLV). In the Waldviertel. Journal for local and regional studies of the Waldviertel and the Wachau. No. 1 (2009) pp. 29-40.

- Markus Holzweber: Research project: Kinderlandverschickung in Lower Austria. In: The Waldviertel. Journal for local and regional studies of the Waldviertel and the Wachau. No. 1 (2010) pp. 283-286.

- Markus Holzweber: "May we send your children?" - The Extended Kinderlandverschickung (KLV) in Lower Austria Presentation, reception and echo in the Nazi era and the Second Republic. In: Yearbook for regional studies of Lower Austria. 79, St. Pölten 2013, pp. 178-425.

- Markus Holzweber: “You wouldn't have dreamed that I am now in the Niederdonau Gau?” The (extended) Kinderlandverschickung in Lower Austria. In: Studies and Research. In: 1945 - Childhood in transition. The lectures at the 35th Symposium of the Lower Austrian Institute for Regional Studies, Laa an der Thaya, July 6th to 8th, 2015 (2019) pp. 149–174.

- Jost Hermand : As a punk in Poland. Extended deportation to Kinderland 1940–1945 . Fischer-Taschenbuch fiTb 11321, Frankfurt am Main 1993, ISBN 3-596-11321-0 .

- Klaus Johann: Limit and stop: The individual in the “House of Rules”. To German-language boarding school literature. In: Contributions to the recent history of literature , 201. Winter, Heidelberg 2003, ISBN 3-8253-1599-1 , pp. 510-560 (chapter “Boarding school literature and Nazism”, including literary and autobiographical treatment of the topic).

- Gerhard Kock: “The Führer takes care of our children” - the children's country deportation during World War II. Schöningh, Paderborn / Munich 1997, ISBN 3-506-74663-4 (At the same time dissertation at the University of Cologne under the title: "The extended Kinderlandverschickung", 1996)

- Carsten Kressel: A comparison of evacuations and extended deportation to Kinderland. The example of the cities of Liverpool and Hamburg. In: Europäische Hochschulschriften , Series III, History and its auxiliary sciences , Volume 715, Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1996, ISBN 3-631-30532-X (also dissertation at the University of Hamburg , 1996).

- Claus Larass: The Children's Train . KLV - The evacuation of 5 million German children in World War II. Ullstein , Frankfurt am Main 1992, ISBN 3-548-33165-3 .

- Erich Maylahn: List of KLV camps , In: Documents and reports on the extended children's country dispatch 1940–1945 , Volume 1, project, Bochum 2004, ISBN 978-3-89733-116-7 (6000 KLV camps according to storage locations, camp names, reception areas and warehouse numbers).

- Thomas Naumann: From Bremen and Herne to Walldürn. Kinderlandverschickungen in National Socialist Germany, In: Dorf unterm Hakenkreuz. Rural dictatorship in southwest Germany 1933–1945, ed. from the State Office for Museum Care Baden-Württemberg and the working group of the seven regional rural open-air museums in Baden-Württemberg, Thorbecke, Ulm 2009, pp. 105–117, ISBN 978-3-7995-8044-1 .

- Martin Rüther, Eva Maria Martinsdorf (ed.): KLV - Extended Kinderlandverschickung 1940 to 1945. Documentation on two CD-ROMs. SH-Verlag, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-89498-091-5 In addition to this, reviews: Fritz Bauer Institute / Critique p. 77 ( Memento of September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 538 kB) as well as a review of hsozkult 2003

- Doris Tillmann; Johannes Rosenplänter: Air War and "Home Front". War experience in the Nazi society in Kiel 1929-1945 . Solivagus-Verlag, Kiel 2020, ISBN 978-3-947064-09-0 .

further reading

- Oliver Kersten: The (extended) Kinderlandverschickung (KLV) . In: Ders .: The National Socialist People's Welfare, especially in the Second World War . Master's thesis at the Friedrich Meinecke Institute of the Free University of Berlin 1993. 160 sheets, p. 49–54. Locations: SAPMO Federal Archives Library Berlin and Friedrich Meinecke Institute of the Free University of Berlin

Web links

- Youth in Germany 1918 to 1945: Kinderlandverschickung NS Documentation Center of the City of Cologne

- Kinderlandverschickung (KLV) LeMO (DHM)

- Circular letter from Reichsleiter M. Bormann dated September 27, 1940 . ( Memento from August 5, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) LeMO (DHM)

- Shoa: deportation to the children's area

- From the bombing war in the Kinderlandverschickung The extended Kinderlandverschickung (KLV) in the Ruhr area during the Second World War ( Memento from July 19, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Research project Uni-Dortmund:

- Children of War: Light in Dark Days . ( Memento from July 19, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 1.32 MB; 4 pages) The Second World War, Duisburg, Bohemia and Tuttlingen ...

- Sources about life during the KLV and further information

- Research project on the children's area in Lower Austria

- Markus Holzweber, lecture about KLV in Niederdonau, held at the symposium of the Lower Austrian Institute for Regional Studies on July 7, 2015 in Laa / Thaya

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gerhard Kock: "The Führer cares for our children" - The Kinderlandverschickung in the Second World War. Paderborn 1997, ISBN 3-506-74663-4 , p. 143. / For the numerical problem, see also: Carsten Kressel: Evacuations and Extended Kinderland Dispatch in Comparison. Frankfurt am Main u. a. 1996, ISBN 3-631-30532-X , pp. 102-111.

- ↑ Hartmut Radebold : Absent Fathers and War Childhood. Persistent consequences in psychoanalysis. Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 2004. / Childhoods in the Second World War. War experiences and their consequences from a psychohistorical perspective. Juventa-Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 2006.

- ^ Wolfgang Keim: Education under the Nazi dictatorship. Vol. 2, Darmstadt 1997, ISBN 3-89678-036-0 , p. 394.

- ↑ Eva Gehrken: National Socialist education in the camps of the extended Kinderlandverschickung 1940–1945. Research Center for School History and Regional School Development, Gifhorn 1997, pp. 139, 166 Note 1.

- ↑ Peter Weidisch: Würzburg in the "Third Reich". In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes, Volume I-III / 2, Theiss, Stuttgart 2001-2007; III / 1–2: From the transition to Bavaria to the 21st century. 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1478-9 , pp. 196-289 and 1271-1290; here: p. 267.

- ↑ Cornelia Schmitz-Berning: Vocabulary of National Socialism. Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-11-013379-2 , p. 352 / Wolfgang Keim: Der Führer ... p. 71.

- ↑ Gerhard Kock: Der Führer ... , p. 76.

- ↑ Gerhard Kock: Der Führer ... , p. 82.

- ^ Gerhard Kock: Der Führer ... , P. 69/70.

- ^ Heinz Boberach: Reports from the Reich. dtv 477, Munich 1968, pp. 117 / 7th October 1940.

- ↑ Gerhard Kock: Der Führer ... , p. 74.

- ^ Eva Gehrken: National Socialist Education ... p. 16.

- ↑ See literature: Gerhard Dabel (Ed.): KLV… ISBN 3-921340-60-8 .

- ^ Gerhard Kock: Der Führer ... p. 14.

- ↑ Volker Böge, Jutta Deide-Lüchow: Bunker life and children’s country dispatch: Eimsbüttler youth in war. Hamburg 1992, ISBN 3-926174-46-3 , p. 172. / List of other countries by Hans-Jürgen Feuerhake: The extended Kinderlandverschickung in Hanover 1940–1945. Bochum 2006, ISBN 3-89733-139-X , p. 21.

- ↑ List by Gerhard Kock: Der Führer ... , p. 97.

- ↑ Böge, both forms of volatile-Lüchow: Bunker life ... , p 171st

- ^ Eva Gehrken: National Socialist Education ... S. 188.

- ↑ Carsten Kressel: A comparison of evacuations and expanded childcare facilities: the example of the cities of Liverpool and Hamburg. Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-631-30532-X , p. 190.

- ↑ Gerhard Kock: Der Führer… , p. 138. Carsten Kressel also comes to these results: Evacuations… , p. 102–111.

- ↑ Gerhard Kock: Der Führer ..., p. 140.

- ↑ confirmed by Reiner Lehberger: Kinderlandverschickung: “Caring action” or “formation education”. In: Reiner Lehberger , Hans-Peter de Lorent (ed.): "The flag high". School politics and everyday school life in Hamburg under the swastika. Hamburg 1986. ISBN 3-925622-18-7 ; P. 371.

- ↑ Gerhard Kock: Der Führer ... , p. 172.

- ↑ Sylvelin Wissmann: It was just our school days. Bremen 1993, ISBN 3-925729-15-1 , p. 303.

- ^ Eva Gehrken: National Socialist Education ... , p. 170 f.

- ↑ Gerhard Kock: Der Führer ... , p. 158.

- ↑ Daily duty roster as an original document.

- ↑ Harald Scholtz: Education and instruction under the swastika. Göttingen 1985, ISBN 3-525-33512-1 , p. 119.

- ↑ Gerhard Kock: Der Führer ... , p. 56. (with reference to Rudolf Benze: National-political education in the Third Reich. Berlin 1936).

- ^ Wolfgang Keim: Education under the Nazi dictatorship. Vol. 2, 2nd edition Darmstadt 2005, ISBN 3-534-18802-0 , p. 56ff. / "Probably almost every German ... had to take part in a camp at least once" - p. 58.

- ↑ quoted from Cornelia Schmitz-Berning: Vokabular des Nationalozialismus , 2nd revised. Ed., Berlin / New York 2007, ISBN 978-3-11-019549-1 , p. 352.

- ^ Eva Gehrken: National Socialist Education ... , p. 172.

- ^ Heinz Boberach: Reports from the Reich. Vol. 9, p. 2154.

- ^ Heinz Boberach: Reports from the Reich. dtv, Munich 1968, pp. 215/216. (March 12, 1942).

- ↑ so the judgment of Gerhard Kock: Der Führer ... , p. 75.

- ↑ Heinz Boberach (Ed.): Reports from the Reich 1938–1945. SD reports on domestic issues. Herrsching 1984, Vol. 14, pp. 5917f. (October 25, 1943).

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Feuerhake: Die Extended Kinderlandverschickung ... , p. 53. / Sylvelin Wissmann: It was just our school days ... , p. 277.

- ↑ so Wolfgang Benz, Ute Benz: Socialization and Traumatization. Children in the time of National Socialism. Frankfurt 1992, p. 22.

- ↑ Gerhard Kock: Der Führer ... , p. 18.

- ↑ Volker Böge, Jutta Deide-Lüchow: Bunkerleben and Kinderlandverschickung ... , p. 212.

- ↑ Volker Böge, Jutta Deide-Lüchow: Bunkerleben and Kinderlandverschickung ... , p. 214.

- ↑ Volker Böge, Jutta Deide-Lüchow: Bunkerleben and Kinderlandverschickung ..., p. 218.

- ↑ Gerhard Kock: Der Führer ... , pp. 138, 143.

- ↑ Gerhard Kock: Der Führer ... , p. 111.

- ↑ Gerhard Kock: Der Führer ... , p. 108.

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Feuerhake: The extended Kinderlandverschickung ... , p. 16.

- ↑ Carsten Kressel: Evacuations , pp. 225/226.

- ↑ Wolfgang Keim: Education under the Nazi dictatorship , p. 154.

- ↑ Jost Hermand: As a Pimpf in Poland. FiTb 11321, Frankfurt am Main 1993, ISBN 3-596-11321-0 , p. 13.

- ^ Gerhard Dabel: KLV. The extended Kinder-Land-Versand. KLV camp 1940–1945. Documentation about the "greatest sociological experiment of all time". Freiburg 1981, ISBN 3-921340-60-8 / more critical in Wolfgang Keim: Education under the Nazi dictatorship , Vol. 2, Darmstadt 1997, ISBN 3-89678-036-0 , quotation p. 154.

- ↑ Bruno Schonig: Crisis experience and educational commitment. Life and work history experiences of Berlin teachers. Frankfurt / M. 1994, ISBN 3-631-42842-1 , p. 132.

- ^ Gerhard Dabel: KLV ... , p. 172.

- ↑ Volker Böge, Jutta Deide-Lüchow: Bunker life and children’s country dispatch: Eimsbüttler youth in war. Hamburg 1992, ISBN 3-926174-46-3 , pp. 213/214.

- ^ Eva Gehrken: National Socialist Education ... , p. 82 f.

- ↑ Gerhard Dabel (Ed.): KLV ..., p. 297.

- ↑ Hilke Lorenz: Children of War. The fate of a generation. List Verlag, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-471-78095-5 .

- ↑ Childhoods . ( Memento from January 29, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Research group Second World War

- ↑ Gerhard Kock: Der Führer ..., p. 340.

- ↑ Carsten Kressel: Evacuations ... , p. 43.

- ↑ Gerhard Kock: Der Führer ... , p. 13, note 5 and p. 343.

- ↑ Carsten Kressel: Evacuations ... , p. 187.

- ↑ Evacuation in Japan ( Memento from February 20, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) - Accessed on March 27, 2007, English-language information from MEXT .