Air war

Air warfare is a form of warfare in which military operations are carried out primarily by air forces and air warfare from other branches of the armed forces . The bombing of undefended cities, buildings and homes violates international martial law . Warfare can be roughly divided into:

- War in the air: Combat enemy aircraft with our own fighters and ground-based air defense .

-

Airborne war: primarily reconnaissance and combat against ground targets, including enemy air forces on the ground, by reconnaissance aircraft and bombers . This is also known as tactical air warfare . Its three tasks or goals are

- the close air support ,

- attacking enemy ground targets in direct proximity to your own units and

- the battlefield closure (tactical targets in the rear area - such as bridges, roads and supplies - fight behind the opposing war front ).

- the strategic air war with the destruction of enemy military and political command and control facilities, including their remote means of production facilities for military defense equipment (aircraft and tanks), power stations and transmission lines, fuel refineries and other (gas) energy storage, air, land and water transportation routes and facilities (airports, seaports and docks) as well as production capacities for the food industry.

The integration of air warfare into general warfare was, according to Daniel Moran, “the central military challenge of the 20th century”. While the original hope that aerial warfare could have a deterrent effect or that it was militarily omnipotent has not been fulfilled, aerial warfare has established itself as a crucial element of combined arms combat .

Important theorists of the air war were or are Giulio Douhet (1869–1930), Billy Mitchell (1879–1936), John Boyd (1927–1997) and John Warden (* 1943).

The beginning

The first warlike use of the airspace consisted of the use of balloons for reconnaissance purposes (" Feldluftschiffer ") and to direct artillery fire .

The first time hot air balloons were used by revolutionary France in 1793 to observe enemy positions; that year the Aéronautique Militaire was founded. A tethered balloon filled with hydrogen , the " Intrépide ", was captured by the imperial army in the battle of Würzburg on September 3, 1796. It is located in the Army History Museum in Vienna and is considered to be the oldest military aircraft that has survived today.

The first air raid on a city took place in the revolutionary years of 1848 and 1849 : During the siege of Venice, the Austrian Lieutenant Field Marshal , artillery expert , weapons technician and inventor Franz von Uchatius suggested that bombs be dropped on the city using unmanned balloons. Three weeks later this first air raid in world history actually took place with 110 balloon bombs manufactured by Uchatius .

During the American Civil War , balloons were occasionally used for reconnaissance.

The first use of an aircraft for warfare took place during the Italo-Turkish War on October 23, 1911 in the form of a reconnaissance flight through Carlo Maria Piazza in a Blériot XI in Tripolitania . The first bombing raid followed on November 1, 1911, when Giulio Gavotti dropped three 2 kg bombs by hand on a Turkish military camp from an Etrich Taube . On March 4, 1912, with a full moon, the first night flight through Piazza and Gavotti took place and on August 17, 1912, the first pilot in the air was injured by gunfire from the ground. Lieutenant Piero Manzini, who crashed on August 25, 1912 during a reconnaissance flight over enemy territory and was killed in the process, was also the first aviator to be killed during a war.

The Italian general Giulio Douhet subsequently founded his theory of bombing war, according to which aircraft should be built specifically for bombing. He is therefore considered to be the founder of the aerial warfare theory. However, his plans to completely prepare Italy for an air war met with great opposition. When he commissioned the construction of bombers without authorization, he was transferred to the infantry according to disciplinary law . Later he was even arrested; only when Italy entered the First World War in 1915 (details here ) and suffered devastating defeats, was he recalled to his position.

During the Mexican Revolution , the northern units deployed nine planes that were flown by American pilots. Thus, after the Italo-Turkish War, this conflict was the second armed conflict in which aircraft were used.

All great powers built air units, but they were still part of the army or navy. See e.g. B. Royal Flying Corps (RFC), French Air Force , USAF , Air Force of the Russian Empire .

First World War

During the First World War , most of the aerial warfare concepts were developed that determined aerial warfare up to and including the Vietnam War and in some cases beyond.

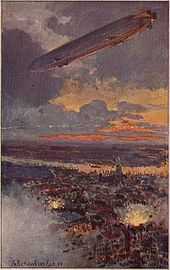

Probably the first air raid of the First World War took place on Liège : on August 6, 1914 at three o'clock in the morning, the German Zeppelin LZ 21 / "Z VI" flew over Liège and dropped bombs that killed nine civilians.

Aerial reconnaissance

At the beginning of the war (1914) the Central Powers and the Entente concentrated mainly on operational long-range reconnaissance. In the course of the war, aerial cameras ("series image devices ") were developed, the photos of which were used by the military for reconnaissance aircraft .

The first decisive success of aerial reconnaissance are the reports from the British Royal Flying Corps ( RFC ), which made it possible to intercept the German advance towards the Marne . This meant that the Schlieffen Plan could no longer be fulfilled and the war on the western front developed into a positional war .

When the trench warfare began, tethered balloons and two-seater radio-equipped aircraft were used to guide artillery fire . The introduction of telegraphic extinguishing spark transmitters from 1915 onwards was synonymous with the actual beginning of aviation radio . Attempts were made especially by the British to drop spies behind enemy lines with balloons and airplanes .

Air superiority

The realization developed that balloons and reconnaissance aircraft had to be attacked directly from the air, as there was a lack of sufficient and practical options for air defense from the ground. The development of real fighters , with which a pilot could fire in the direction of the aircraft's longitudinal axis without the help of an on-board gunner, began with the French pilot Roland Garros . He attached a forward-pointing machine gun to a Morane-Saulnier L and reinforced the rear of the propeller so that he could fire through the propeller circle without damaging the propeller. An interrupter gearbox developed by Fokker for the propeller-synchronized triggering of the machine guns was a useful further development of this method. The Fokker EI equipped with it is considered the first mass-produced fighter aircraft in the world.

On the Allied side, they initially made do with a pusher propeller arrangement , later with rigidly mounted weapons that were aligned over the propeller circle. The structures for leading units in combat were borrowed from the cavalry and continuously developed. The British pilot Lanoe Hawker advocated a disciplined association flight at the RFC early on. On the Allied side you stayed with the division into squadrons (Engl. Squadron ), on the German side it came to the preparation of the seasons , the numbers correspond to the squadrons and squadrons summarizing that several seasons.

In the course of the war, the Allies set up their units as separate armed forces that were allowed to operate independently of the army command. A little later, regular patrol flights were added, through which the French and British could control the entire western front.

The Germans responded by carrying out "restricted flights". With this tactic, the German crews had to be stationed near the front in order to block the airspace through constant surveillance . However, a large number of fighter planes were necessary for such a procedure, which had to operate in a concentrated manner in a narrow area and were therefore not available for other operations.

In October 1916, at the suggestion of the experienced fighter pilot Oswald Boelcke, the German air force was restructured , which was now set up as an independent armed force alongside the army and navy . In addition, Boelcke selected some outstanding pilots in his own ranks, whom he personally trained in aerial combat and deployed in the legendary " Jagdstaffel 2 ". In order to pass on his experiences, he summarized the most important basics of aerial combat in the Dicta Boelcke .

When the Americans intervened in the fighting in 1918, the Allied air forces were able to push the Germans back through their numerical superiority. Despite their armament efforts, they had to limit themselves to achieving air superiority in at least a limited area.

Strategic bombing

Bombs and propaganda material were dropped from planes over enemy cities at the beginning of the war.

Liège and Antwerp were the first cities to be bombed by a German zeppelin on August 6 and 24, 1914 . The first German bombing on British soil was carried out by Lieutenant Hans von Prondzynski on December 24th in Dover . The bomb he dropped missed the envisaged target Dover Castle and landed in the parish garden of St. James. A British machine that ascended afterwards was unable to locate the attacker. On January 19, 1915, the eastern English cities of Great Yarmouth and King's Lynn in Norfolk were bombed by the L3 and L4 zeppelins. The first bombing raid on London was carried out on May 31st.

Almost simultaneously with the "Dorana" and the "Lafay" the first bomb target devices were developed. The hit probability could be significantly improved, although they were very simple.

In 1916 the bombing attacks were intensified. Now, in addition to high- explosive bombs , incendiary bombs were also used, with which great damage was caused, especially in England. The most devastating attacks were carried out by German planes between March 31 and April 6, forcing the British to darken or shut down their workplaces in case of danger.

Initially, the Germans used airships in particular for bombing. From 1917, large aircraft , later also giant aircraft , were built as strategic bombers in Germany, which were used in bomb squadrons of the Supreme Army Command and giant aviation departments. They replaced the airships as the main means of bombing. The large aircraft reached higher speeds and were therefore more difficult to intercept.

Overall, the bombings had a military and strategic benefit that went far beyond the material damage. Great Britain had to invest considerable resources in building an air defense system and using large numbers of air units for home defense rather than for combat at the front. The production losses caused by bomb alarms were greater than the damage directly caused. In total, around 1,400 people lost their lives as a result of German air raids on England.

A total of 15,471 bombs were dropped over the German Reich, killing 746 people and injuring 1843. The state of Baden was hardest hit, with 678 dead and wounded.

See also: Zeppelins in World War I and Schütte-Lanz

Ground combat support with attack aircraft

During the First World War, fighters were already used to fight infantry and tanks . In order to attack enemy soldiers, the crews not only made use of the on-board machine guns, but also threw long thick nails, so-called aviator arrows (French fléchettes ), from the aircraft. In use against tanks, bombs were used that were initially thrown manually at their target. Later in the war, the bombs were hung from the underside of the aircraft and notched over the target.

In the war year 1917, so-called battle squadrons were set up on the German side, the planes of which were specially designed for use against ground targets. The aircraft of the battle squadrons were armored on their underside and engaged in low-flying ground combat. Due to the technical possibilities of armament and targeting devices at the time, the use of the battle squadrons was limited. On the Allied side, regular fighters were used for such purposes, which also intervened in the land fighting. Admittedly, the latter strategy turned out to be too disadvantageous overall - the fighter pilots were not trained for attacks on ground targets, the armament of the fighter aircraft against ground targets was not very damaging, conversely, the largely unarmored fighter models were extremely sensitive to concentrated defensive fire, even of simple infantry weapons, which led to high losses with such weapons Missions led. As a consequence, in the further development of combat aircraft after the war, the Allies also followed the principle of developing and using specialized attack aircraft or fighter-bombers for attacks against ground targets .

Air defense

Since research on anti-aircraft guns was only carried out in Germany before the war , the soldiers at the front had to improvise until appropriate weapons were available on all sides.

Simple machine guns lacked the ability to aim properly. Enemy balloons in particular were difficult to shoot down, which is why fighting in the air was initially more important. On August 22, 1914, the first British aircraft was hit by gunfire, whereupon it crashed over Belgian territory. Manfred von Richthofen fell victim to machine gun fire from the ground.

In the German cities, special posts were supposed to send reports to central air control stations, which then decided on measures such as air raid alarms or barrages. In addition, passive air defense was intensified , ranging from educating the population to signals from church bells, gunfire or steam and motor sirens .

Naval aviators

During the First World War, the British began to convert several warships into seaplane carriers. However, these were only suitable for seaplanes that took off from the deck and landed near the tender after their mission. Special cranes then lifted them on board. The HMS Ark Royal (II) is widely regarded as the first aircraft carrier, but was only equipped with seaplanes and took part in the Battle of the Dardanelles .

The HMS Furious , a converted British cruiser , launched an attack on the Zeppelin hangar in Tondern on July 19, 1918

In 1910 the training of naval pilots began in Austria-Hungary . In 1911 the first sea flight station was built in the naval port of Pula . At the end of 1915 the k. u. k. Naval Air Force over 65 combat-ready seaplanes. Due to the steadily increasing number of Italian bombings, the use of fighter planes was soon planned. After building our own prototype, the decision was made to purchase German Fokker fighter planes. Liner Lieutenant Gottfried von Banfield (the "Eagle of Trieste") achieved the first night aerial victory in aerial warfare on May 31, 1917. At 10:30 p.m., he used his Lohner flying boat to force an Italian sea flying boat to land near Miramare Castle .

Although the first take-off from a ship in the USA and the first landing on the USS Pennsylvania in 1911 , it was not until 1918 that the first aircraft carrier suitable for take-off and landing was completed, the HMS Argus , a converted passenger ship . This came too late for a war mission in the First World War.

Romantic hero image

During the First World War, French newspapers coined the term as d'aviation ( flying ace ) for pilots who shot down at least five enemy machines. The first flying ace was Adolphe Pégoud , the three leading "aces" of the First World War were Manfred von Richthofen (Germany), René Fonck (France) and Billy Bishop (Great Britain). Newspapers (and later also films) created a romantic image of aviator breeds as "modern knights of the sky".

Air forces involved

- Aviation Militaire (Belgian Air Force)

- Royal Flying Corps / RFC (British Air Force, until 1917)

- Royal Naval Air Service / RNAS (British Naval Air Force , until 1918)

- Royal Air Force / RAF (British Air Force, from 1918)

- German air force

- Aéronautique Militaire (French Air Force)

- Corpo Aeronautico Militare (Italian Air Force)

- Austro-Hungarian Air Force (Austro-Hungarian Air Force)

- Osmanlı Hava Kuvetler (Ottoman Air Force)

- Императорский военно-воздушный флотъ (Russian Air Force)

- Air Service of the US Army (US Air Force)

The aircraft production of the belligerent powers of the First World War

| country | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | Total production |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| German Empire | 1,348 | 4,532 | 8,182 | 19,746 | 14,123 | 47,931 |

| Austria-Hungary | 70 | 238 | 931 | 1,714 | 2,438 | 5,391 |

| United Kingdom | 245 | 1.933 | 6,099 | 14,748 | 32,036 | 55,061 |

| France | 541 | 4,489 | 7,549 | 14,915 | 24,652 | 52,146 |

| United States | - | - | 83 | 1,807 | 11,950 | 13,840 |

| Kingdom of Italy | - | 382 | 1,255 | 3,871 | 6,532 | 12,031 |

| Russian Empire | 535 | 1,305 | 1,870 | 1,897 | - | 5,607 |

Interwar period

The aerial combat tactics developed from 1914 to 1918 formed the cornerstone of the future air warfare. The strategy of the air war was rethought by theorists like Billy Mitchell and Giulio Douhet and saw the implementation of unrestricted bombing as a means to decide the war quickly and without the heavy losses experienced in the First World War in one's own troops. The air forces of several great powers, including the United States, Great Britain and Germany, based the construction of their air fleets on such considerations.

In Morocco, after several defeats in 1923, Spain switched to the use of chemical weapons from the air, which is outlawed under international law, in the Rif War , in order to make large stretches of land uninhabitable. The German Reichswehr supported the Spanish chemical weapons use logistically and conceptually through the chemical weapons specialist Hugo Stoltzenberg in order to benefit from the Spanish experience, since a chemical weapons ban applied to Germany under the Versailles Treaty.

The industrialized countries promoted technical developments, and the implementation of international competitions such as the Schneider Trophy led to a technological head-to-head situation among the former opponents of the World War. The main achievements were liquid-cooled in- line engines , jet engines , rocket drives , radar , retractable landing gears, all-metal construction, on-board radio and pilot academies.

Between the world wars, aircraft were mainly used in the colonies . For example, during the Italo-Ethiopian War of 1935 , the Italians threw poison gas grenades from planes at Ethiopian civilians.

The Soviet Union, Germany and Italy used the Spanish Civil War to test their planes and troops. Germany in particular used the war to provide the pilots with combat experience and, with the Condor Legion , set up a unit in which around 20,000 German soldiers fought through a rotation process by the end of the war. The civilian population was massively bombed. The city of Guernica was destroyed by German bombers , which was the first violation of the German Air Force against international martial law .

Second World War

Europe

German air raids

When the Second World War began, it was a primary goal of the German Air Force to achieve air superiority over Poland in order to support its own troops in their Blitzkrieg campaign. The pilots used the experience of the Condor Legion from the Spanish Civil War .

On the invasion of Poland two German air forces were involved. The first shot down in World War II was achieved by an aircraft from Sturzkampfgeschwader 2 "Immelmann" . On the morning of September 1st, the German air force flew an air raid on Wieluń , in which the small military town was largely destroyed. According to Horst Boog , the former head of the military history research office of the German Armed Forces in Freiburg, the attack was a tactical attack on the Polish 28th Division and a cavalry brigade, which had been discovered in Wielun by a reconnaissance officer on the eve of the attack. Historian Jochen Böhler has a different opinion . In his opinion and others, the German Air Force is said to have razed numerous Polish locations to the ground just to test the effectiveness of the bombings they had planned in 1933.

In the days that followed, the Germans were able to gain control of the air. The propaganda even reported the total annihilation of the Polish Air Force, although it was still operational. However, most of their planes were hopelessly out of date. Many of the Polish bombers, such as the Karás machines, were unable to fight the German tank units effectively. Only a few modern aircraft, such as the PZL.37 Łoś bombers , could bomb columns of tanks in a confined space. The losses on the Polish side were extremely high because not enough hunting protection could be provided.

Heinz Guderian wrote after the war's end in his autobiography, the High Command of the Wehrmacht (OKW) had decided that in the Polish capital Warsaw included more than 200 000 men counted Polish military units with an "effective fire" to force to surrender to a loss- house fighting in to avoid a big city. In addition to massive shelling by the artillery, dive bombers (Stuka) were also used to combat “tactical point targets”. Because of the attacks and the military situation that had become hopeless at the time, the Polish units capitulated on September 28, 1939. In these first weeks of the war, Warsaw had already lost around ten percent of its building fabric. According to historian Vogel, the administrative and logistical center of Poland was destroyed by bombing and shelling.

The British pre-war concept of air warfare had long-range bombing raids on enemy targets during the day. The German “Freya” and “Würzburg” radar devices installed in the meantime, however, enabled the Air Force to successfully intercept them, so that the Royal Air Force had to switch to night air raids after high losses.

During the western campaign , the Germans used the Blitzkrieg tactic, i.e. the combination of air and land forces, and thus managed to defeat France . The Netherlands capitulated just four days after downtown Rotterdam was destroyed by a German air raid . Around 800 people died as a result of this air strike and 80,000 Rotterdam residents were left homeless.

As part of a planned bombing by Kampfgeschwader 51 on Dijon , 67 bombs were supposedly dropped on Colmar , but actually on Freiburg im Breisgau . 57 inhabitants died. Adolf Hitler used this bombing as evidence that the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had started terrorist attacks against the civilian population by bombing Freiburg.

After the defeat of France, Britain was to be conquered by a large-scale invasion or brought to its knees by the air force. The ensuing Battle of Britain , however, led to the defeat of the Luftwaffe. There were over 20,000 deaths in London alone (" The Blitz "). The destruction of the structure was enormous; Thousands of buildings were affected in central London alone. On August 15, 1940, the Luftwaffe flew 1786 missions against England. From November 1940 onwards, the attacks were extended to other cities, especially industrial centers: Birmingham, Coventry , Manchester, Sheffield and, in 1941, Clydebank, Liverpool and Plymouth. On the night of December 29-30, 1940, one of the most devastating attacks on the City of London resulted in what has been referred to as the "Second Great Fire of London", alluding to the Great Fire of London in 1666. After the attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, the air raids on England became considerably less frequent.

On April 6 and 7, 1941, 484 (according to other sources 611) German fighter and fighter planes under the code name "Criminal Court" bombed the undefended Belgrade . The civilian population should be hit in the first wave; the second wave was intended to hit military installations and administrative centers. An unknown number of people died. The figures range from 1,500 to 30,000 dead. In addition, the historic city center with the government district was largely destroyed. The destruction of the administrative center of Yugoslavia was the prelude to the subsequent occupation of the country.

After the air force later, in the course of Operation Barbarossa , mostly had the air superiority, it had to accept another defeat in mass air raids on Moscow . The goal of destroying the city or at least important supply hubs such as power and waterworks was only achieved to a limited extent. As momentous miscalculation also needs to Hermann Goering announcement shall, at the Battle of Stalingrad to supply an encircled army over the winter from the air, after the city had been attacked in the offensive with 600 aircraft.

On the night of August 26th to 27th, 1944, 50 German fighter pilots dropped bombs on Paris . That was after the surrender of the German Wehrmacht commander-in-chief of Greater Paris, General Dietrich von Choltitz , on August 25, 1944, 2:45 p.m. (to Colonel Henri Rol-Tanguy, the leader of the Paris Resistance / FFI). The bombing killed 213 people and wounded 914. Almost 593 buildings were damaged or destroyed.

Bombing raids on Germany

After the Wehrmacht had started the campaign in the west on May 10, 1940 , the Royal Air Force flew an attack on Munich-Gladbach (now Mönchengladbach ) with 35 bombers on the night of May 12, 1940 . She later flew several minor attacks on German cities, including eight on Berlin . The German Air Force first attacked London on September 7, 1940 (→ The Blitz ), followed by the " Operation Moonlight Sonate ", the attack on Coventry on 14/15. November 1940. Since military action on the European mainland was no longer possible for the British after the occupation of France by German troops , air strikes were the only way to hit the German Reich.

A special form of passive air defense was the construction of dummy installations . During the Second World War z. B. About a third of the 1.5 square kilometer built-up site of the Krupp cast steel factory, mainly facilities in the outer area, completely destroyed, another third partially. In order to avert and deceive Allied air raids, a mock-up of the cast steel factory was created on the Rottberg near Velbert from 1941 , the so-called Krupp night glow system . Initially, it attracted a few attacks, but lost its effectiveness from 1943 onwards as the aviators were better able to orient themselves, including the introduction of radar . During the first attack on the actual cast steel factory in March 1943, the Allies dropped 30,000 bombs, which also bombed surrounding housing estates and thus civilians.

After it became clear from the Butt Report in August 1941 that the tactical targets had been badly hit, it was considered to launch area attacks on German cities. The civilian population, who were to be spared according to the international martial law , should also be hit in order to break their morale ("moral bombing ") and to strengthen the resistance against the Nazi regime . This corresponded to the decision of Churchill's wartime government , which, after submitting the " dehousing memorandum " by Frederick Lindemann , had decided to extend the air war to civilian targets. The British Air Ministry issued the “ Area Bombing Directive ” as a new leitmotif on February 14, 1942 . Hitler had already tried to do something similar on August 2, 1940 with directive No. 17 .

Precise daytime attacks were still very lossy because of the German air defense at the beginning of the war; therefore the RAF Bomber Command flew the area attacks against German cities at night. A high percentage of incendiary bombs were dropped, which caused devastating damage (sometimes fire storms ) in the residential areas of the cities hit . Such incendiary bombs - such as the electron thermite rod incendiary bomb - had been designed and tested long before the war.

After Arthur Harris was appointed Commander in Chief of the British Bomber Command in February 1942, he developed the plan for a thousand bomber attack . This should maximize the effect in the target and reduce the British casualty rate by overloading the German flak and night fighters.

On the night of May 30th to May 31st, 1942, the RAF flew the first thousand-bomber attack, the " Operation Millennium " on Cologne , with 1,047 planes and 1,455 tons of bombs ; there, over 3,300 houses were completely destroyed and 474 people killed in 90 minutes. The RAF lost 41 machines, significantly fewer in percentage than in previous attacks. The majority of the 602 machines were twin-engine Vickers Wellington . In addition to the twin-engine Hampden , Manchester and Whitley , a total of 292 four-engine Halifax , Stirling and Lancaster were also used against Cologne .

Previously, the air raid on Lübeck on March 29, 1942 had caused great damage there. With this successful attack, the tactics of area bombing were tested for the first time.

In August 1942, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) also entered the air war over Europe. During the day, they flew precision sighting attacks on targets in northern France. In the case of attacks over France, when the cloud cover over the target area was closed, no opportunity targets were selected, but rather the bomb load to the home base was withdrawn, in contrast to attacks on Reich territory. When they started attacking targets in the German Reich in 1943, they suffered heavy losses due to the Luftwaffe's anti-fighter defense due to a lack of escort protection . The attacks on Essen as well as Regensburg and Schweinfurt (1943) in particular resulted in large losses (see also Operation Double Strike , air raids on the Ruhr area ).

The air raid shelter order issued on September 18, 1942 forbade forced and " Eastern workers " as well as prisoners of war , who were mostly used as auxiliary workers in the Reich, from access to the air raid bunkers . This led to a disproportionately high number of aerial warfare deaths among these people, and the Reich government, especially the Ministry of Armaments , endeavored for economic reasons to dissuade the cities from this radical practice. In cities like Berlin or Frankfurt / Main, Jews were also prohibited from entering the air raid shelters.

At the Casablanca Conference in January 1943, the very general Casablanca Directive was agreed. Despite reservations on the part of Winston Churchill , a joint approach by British and American strategic bombers ( Combined Bomber Offensive ) against the German Reich was agreed. The Americans wanted to fly precision attacks by day and the British to intensify their attacks at night. Air strikes should take place around the clock. This is considered the political basis for the procedure until the end of the war.

From July 25 to August 3, 1943, units of the RAF and the 8th US Air Force flew a series of air raids (five by day and two by night) on Hamburg , which became known under its military code name " Operation Gomorrah ". These were the heaviest attacks in the history of the air war to date. The fifth of these attacks resulted in a firestorm ; around 30,000 people died, five districts were badly damaged and three destroyed.

In the attack on July 25, 1943 British bombers dropped for the first time tinfoil from strips to the German "Würzburg" - Radio metering devices disturbing. The reflections of the thrown chaff prevented the exact location of the British aircraft and made effective countermeasures impossible. The decoys were 26.5 cm long and thus corresponded to half the wavelength of 53 cm of the German radio measuring devices. The frequency of 560 MHz ( decimeter waves ) used was determined during the examination of parts of a "Würzburg" device that were captured in February 1942 from the British commando Operation Biting in northern France. Only three percent of British planes were shot down, otherwise it was often more than ten percent.

The second major British attack with 739 bombers on the night of July 27th to 28th 1943, favored by a week-long heat wave and drought, resulted in a firestorm. About 30,000 people died in this attack.

In the fall of 1943, strategic attacks by the Allied bombers on sites in the German armaments industry essentially weakened German efforts. Exact sketches of the location of steelworks, tank, weapon, ball-bearing and especially aircraft factories as well as V-missile production facilities were sent to Allied general staffs via the resistance group around Chaplain Heinrich Maier , so that precise air strikes on armaments factories are possible and residential areas in particular are spared. With this information, the Allies were able to make decisive investments in the war. At the aircraft factory south of Vienna, for example, there was a significant slump in production of single-engine fighters. In the Wiener Neustädter Flugzeugwerke , after the most successful attack on November 2, 1943, the monthly production rate of Messerschmitt Bf (Me) 109 fell from 213 units in October to 50 in November and 37 in December 1943. All of this resulted in a decisive weakening of the German Air Force a moment when the Allies increased their aircraft production significantly or introduced more powerful escort fighters. The Americans and British were able to destroy the German air force through attrition. It was possible to increase German aircraft production by relocating the manufacturing facilities, but the German fighter pilots were increasingly wiped out by the now overwhelming Allied excess weight, which could no longer be made up.

In February 1944, the Americans and British launched the so-called " Big Week " (German: "Große Woche"), a series of Allied air raids on selected targets in the German arms industry . Between February 20 and 25, 1944, around 6000 bombers and 3670 escort fighters were used for this purpose. The Big Week was the beginning of the decisive phase of the Allied strategic air war against Germany.

In the course of 1944, the Allies finally gained through the increased use of long-range escort fighters of the type P-51 Mustang finally the air superiority . The German (armaments) industry was subsequently forced to relocate further parts of its production to caves, tunnels and the like. Nevertheless, the production of war goods could in some cases even be increased through the use of prisoners of war , forced labor and concentration camp prisoners .

The particularly intense air raids on Dresden in February 1945 and the air raids on Kassel , Braunschweig , Magdeburg , Würzburg , Darmstadt , Pforzheim , Hildesheim , Nordhausen , Nuremberg , Koenigsberg , Halberstadt and Swinoujscie achieved notoriety.

The book Der Brand ( ISBN 3-549-07165-5 ) published by Jörg Friedrich in 2002 sparked controversy . Critics accused it of missing the historical context; the Allied attacks on the civilian population were portrayed in emotional terms as war crimes . It was also criticized that Friedrich brought the military actions linguistically close to the crimes of the Nazi regime . Hans-Ulrich Wehler : “The 'Bomber Group 5' mutates into a 'Einsatzgruppe', bomb victims become 'exterminated' and their cellars are declared 'crematoria'. That is the blatant linguistic equality with the horror of the Holocaust . ” In this context, the historian Hans Mommsen has pointed out that the term“ extermination ”was used by Churchill himself. Friedrich himself denied having intended conceptual parallelization; not every crematorium is in an "extermination camp like in Auschwitz"

The British historian Frederick Taylor admits that the case of Dresden, from the Allied perspective, would not have been an “open city”, but a “functioning enemy administrative, industrial and transport center […] close to the front . “( F. Taylor : Dresden, February 13, 1945, page 436).

The British philosopher AC Grayling (Birkbeck College, University of London) summarized the research in his book Among the Dead Cities: The History and Moral Legacy of the WWII Bombing of Civilians in Germany and Japan as follows: area bombing is disproportionate and militarily unnecessary been; it violated “humanitarian principles” and “recognized standards” of Western civilization and was “morally very wrong”. (P. 276 f.)

Even during the war, the Allies grappled intensively with the question of whether their deeds were correct. The United States Strategic Bombing Survey , a commission of over 1,000 experts from the military and the private sector, examined the effects of the bombing. After the end of the war, German executives from government and industry were also interviewed. Around 200 detailed reports were created.

Air landings

During the Second World War, the Germans first used paratroopers to drop troops behind the front, which the Germans used to support their lightning war tactics . After Dombås was captured from the air, the conquest of the Belgian Fort Eben-Emael and the Meuse bridges for the Fall Gelb advance were a major success. Paratrooper missions are often costly because the soldiers are easy to hit in the air, can get caught in obstacles and the soldiers land scattered. It takes a certain amount of time before the landed units are ready for combat. Heavy equipment could not be transported back then.

With the airborne battle for Crete, the Germans undertook a purely operational large-scale deployment of paratroopers. The Germans were able to conquer Crete, but the losses were enormous. The troops tied here by losses were then not available for the campaign against the Soviet Union . After the mission in Crete, Adolf Hitler came to the conclusion that the use of paratroopers for the purpose of conquest had lost its element of surprise. In the course of the further war there were several planned air landings and in 1943 the Leopard company with the capture of the island of Leros after a paratrooper mission. The last major parachute jump was carried out in December 1944 during the Ardennes offensive with the Stößer company by a paratrooper combat group. They jumped in blowing snow and strong winds and were scattered very far.

The Allies drew different conclusions from the Battle of Crete and set up paratroopers themselves. These were used during the landing operations in Sicily with Operation Husky , in Normandy with Operation Overlord and during Operation Market Garden , during Operation Market, the largest airborne operation of the Second World War to create an advance corridor for the ground troops and the Capture of the bridges in it took place. Only in Operation Varsity , which was carried out on March 24, 1945 in the Wesel - Rees area as part of the Rhine crossing, did the number of airborne troops deployed in one place exceed the Market record within one day .

In addition to paratroopers, cargo gliders were also used to transport airborne infantry and vehicles (later also light tanks).

New weapons

During the war from the air , from 1944 Germany first used the Fieseler Fi 103 cruise missile and a little later with the surface-to-surface missile unit 4, the V1 and V2, which were known as " retaliatory weapons " for propaganda . The V1, with its simple rudder control via heading gyro , could hit a large-scale target such as the city of London, while the V2 ballistic missile, controlled by an inertial navigation system, provided more precise targeting. But their use did little to change the course of the war. Since there was little or no defense against the V2 rocket, the attacks spread tremendous horror among the civilian populations of Great Britain and Belgium ( Antwerp ) and claimed around 8,000 victims.

Towards the end of the war, the German Air Force successfully deployed unguided air-to-air missiles ( R4M ) and, on a small scale, the remote-controlled Ruhrstahl X-4 for war in the air . For defense from the ground, the Peenemünde Army Research Institute developed the anti-aircraft missile “ Wasserfall ” from the V2 without being used.

The Reich Aviation Ministry also promoted the development of jet and rocket propelled aircraft with which the Germans wanted to counter the increasing Allied bombing attacks. However, many of these modern aircraft technologies were used too little, too late, or not at all. In particular, the initial technical unreliability and the lack of operating materials as well as trained personnel prevented a noteworthy success.

These were used as miracle weapons by the propaganda in order to maintain the will to persevere in the face of the hopeless situation in all areas.

See also: Messerschmitt Me 262 , Me 163 , Heinkel He 162 and Arado Ar 234

Pacific War

Air War in the Pacific

In the Pacific War , aerial warfare completely changed maritime warfare . The war was mostly fought at sea and consisted of numerous landings. Since much of the fighting took place in impassable rainforest areas and it was difficult to land heavy weapons, air support also became more important.

Japan and the United States maintained large fleets of aircraft carriers that made it possible to quickly show up in front of a target, fly a major air strike, and then disappear. This tactic surprised the Americans during the Japanese air strike on Pearl Harbor that triggered the war . The naval battles also changed; the battleships and cruisers lost more and more importance, since the battles were now fought by torpedo bombers at distances that were too great for the ship artillery .

In May 1942, the Battle of the Coral Sea was the first sea battle fought exclusively by carrier aircraft. Most of the Japanese and US carrier fleets met a month later at the Battle of Midway . Both sides had recognized the value of the carrier units, and the Japanese tried in battle to crush the US carrier fleet in addition to conquering Midway . One US American aircraft carrier and all four Japanese aircraft carriers were sunk, leaving the Japanese fleet with only two large carriers and losing strategic weight in the Pacific.

Bombing raids on Japan

As early as 1942, the Americans carried out a surprise attack from aircraft carriers on the Japanese motherland, which would later go down in history under the name " Doolittle Raid ". As the Allies were able to conquer more and more islands near Japan, it was also possible to attack directly with heavy B-29 bombers.

The air raids on Tokyo in February and March 1945 were the heaviest bombings in the entire war.

- On February 25, 1945, 174 B-29 Superfortress bombers dropped napalm bombs on Tokyo . The napalm bombs caused enormous casualties among the civilian population. Around 3 km² of urban area were destroyed in the process. The AN-M69 Napalm bombs were used for the first time in the attack . The M69 bombs weighed 2.3 kg and was added to each 38 pieces in the 227 kg heavy M19 -Streubombe n packed.

- During a night attack on the night of 9/10 March 1945, the 21st US Air Force flew another air raid against Tokyo. 334 B-29 bombers dropped around 1,500 tons of napalm bombs on the Japanese capital. 41 km² of urban area was completely destroyed.

According to Japanese figures, 267,171 houses were victims of the flames. 1,008,000 people were left homeless. Officially, the losses are given as 83,793 dead and 40,918 injured. Many buildings in Tokyo were built according to the old timber construction and therefore caught fire quickly.

Within three weeks, "9,365 tons" of M69 Napalm bombs were dropped on the cities of Tokyo, Osaka , Kobe and Nagoya , which reduced more than 82 km² of urban area to rubble. With that the first supply of napalm bombs was used up.

The United States developed the atomic bomb during the war . Their effects put everything previously known in the shade; it shaped the following decades ( Cold War ) like no other weapon (see balance of terror , arms race ). In nuclear bombs by nuclear fission (or in the hydrogen bomb , the nuclear fusion ) Explosion energy is released, in contrast to a chemical reaction in conventional weapons.

Atomic bombs

In August 1945, the US used two atomic bombs on Japanese cities. The Little Boy atomic bomb was detonated over Hiroshima and the Fat Man atomic bomb over Nagasaki . The effects were devastating.

- In Hiroshima, 70,000 to 80,000 people died instantly. A total of 90,000 to 166,000 people died in the drop, including the long-term consequences, according to different estimates up to 1946. The bomb killed 90 percent of people within a 0.5 kilometer radius of the center of the explosion and 59 percent within 0.5 to 1 kilometer. The residents of Hiroshima at that time are still dying of cancer as a long-term consequence of radiation.

- When the atom bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, 22,000 people died immediately and, according to various estimates, 39,000 to 80,000 people died in the following months. The survivors of the atomic bombs are known as Hibakusha in Japan .

Cold War

After the Second World War, the Cold War broke out , in which the USA and the Soviet Union faced each other. This ensured massive funding for weapons and military technology on both sides. The results of research in the German Reich were used on both sides and researchers were recruited ( Operation Overcast ). Nuclear weapons in particular played an important role in this conflict. Initially, the use of bombers was planned. Thus, bomber formations were the strategic support. In order to avoid the destruction of the bombers on the ground and the consequent loss of recoil ability, strategic bomber fleets were kept in the air for 24 hours by air refueling . The importance of the bombers changed only when the development of intercontinental ballistic missile ( Inter-Continental Ballistic Missile ICBM progress). Initially, ICBMs required long refueling and launch phases, so that an attack would have been discovered by the enemy days in advance. But in further development the weapons became more and more effective and had the advantage over bombers that they could reach any point on earth within minutes. Once started, they were practically unstoppable.

Air reconnaissance therefore became more and more important. The American Lockheed U-2 , which, thanks to its extreme flight performance, initially allowed the USA to fly safely over the USSR, became particularly famous . On May 1, 1960, however, the Soviet air surveillance managed to shoot down a U-2 and arrest the pilot Francis Gary Powers . After that, the importance of aerial reconnaissance with airplanes continued to decline, as the continuously improved satellite technology made unmanned reconnaissance possible directly from space. The importance of aerial reconnaissance became apparent in the Cuban Missile Crisis .

In numerous proxy wars , both sides used their technology against each other.

Korean War

The Korean War of 1950 offered the USA and the Soviet Union the opportunity to test their new aircraft technologies and compare them to one another. The United States supported South Korea , while the Soviet Union unofficially made aircraft, trainers and pilots available to the North Korean troops .

Propeller machines were increasingly replaced by jets during the war. On November 10, 1950, the first jet-versus-jet fight occurred in which an F-80 Shooting Star shot down a MiG-15 .

The Soviet MiG-15 were superior to the aircraft of the US troops. Although the US troops were able to improve the situation with the introduction of the F-86 , this was not superior to the MiG-15 either. In order to be able to thoroughly examine a MiG-15, the US offered every opposing pilot who would land with an intact machine on a US base $ 100,000 and asylum. Only after the end of the war did a North Korean pilot fled to the south. Its MiG-15 can still be admired in a USAF museum today. The area that the MiG-15 could reach was called " MiG Alley " by American pilots . The countermeasures of the US pilots were hampered by political restrictions. For example, the bases of the MiGs in China were not allowed to be attacked, and flying over the Chinese border was also generally prohibited. For example, because of the MiGs, the USAF was forced to conduct its B-29 attacks at night. It was only with the introduction of the F-86E that the balance in the fighters was restored. The majority of the ground attacks, however, were with propeller-driven planes such as the North American P-51D "Mustang", the Douglas B-26 "Invader", the Fairey "Firefly" FB.5, the Hawker Sea Fury FB.11, the Douglas AD-1 Flown “Skyraider” or the Vought AU-1 “Corsair”. Jet aircraft used for ground attacks were, for example, the F-84 “Thunderjet”, Gloster “Meteor”, Grumman F9F “Panther” or the McDonnell F2H “Banshee”.

Since the Soviet Union did not want and was not allowed to officially interfere in the conflict, the Soviet pilots were required to fly very defensively and behind the front. Due to this fact and the larger number of aircraft, the USA was able to achieve air supremacy at the end of the war. According to recent research from the USA, the shooting rate was last at 4.4: 1 for the USA. The American loss account only counts the own losses that were shot down directly over the combat area. Aircraft that go down over their own territory or that have to be scrapped are not included in the statistics as kills.

In order to weaken the north, the USAF carried out numerous area bombings , as were later carried out in Vietnam. In fact, more napalm was dropped in the Korean War than in the Vietnam War; in the second half of 1950 alone it was more than 1 million gallons (3,785,400 liters). Irrigation systems and power plants were also targeted; the destruction of numerous dams resulted in floods.

When China was massively supporting North Korea with troops, American commander-in-chief Douglas MacArthur called for the air war to be extended to the People's Republic, which was one of the reasons for his dismissal by President Truman .

Vietnam

In Vietnam in 1965, the US began one of the most devastating bomb wars in history. Defoliant ( Agent Orange ) and napalm were used, among other things . The civilian population was particularly hard hit by the bombing. The napalm bombs, generating up to 1200 degrees Celsius, inflicted severe burns on those who did not die immediately.

More bombs were dropped on Vietnam than in all theaters of war combined during the Second World War. In North Vietnam, aerial warfare was used primarily as a political tool. In Washington it was decided what to attack when and where. In 1964, North Vietnamese ports were bombed in "retaliation" for an attack by speedboats. From 1965, Operation Rolling Thunder was supposed to bring the North Vietnamese to an armistice. At the same time, however, the US armed forces were forbidden from bombing the major ports, airfields or cities, as it was feared that they would meet Soviet "advisers". It was not until 1972 that the supply of North Vietnam was stopped by mining the ports and the massive bombing of the cities during Operation Linebacker . Then there was a ceasefire between the United States and North Vietnam.

In the rest of the air war, however, the USA did not succeed in decisively hitting the armed forces of North Vietnam and the Viet Cong. B. to cut off the supply on the Ho Chi Minh Trail through Laos .

The massive use of guided missiles was new in the Vietnam War. As early as 1965, North Vietnam used the "SA-2" for air defense, and in 1972 the portable "SA-7" as well. The US used anti-radar guided missiles, remote-controlled or television-controlled bombs. From the beginning of the 1970s, laser-guided bombs were used.

In Vietnam, the relationship between air and ground operations changed. The aerial warfare became more and more important, and operations of the army became less and less and more strongly combined with air strikes. On the one hand, the aerial warfare demands fewer of its own victims and runs “cleaner” for the soldiers, since there is no direct contact with the enemy. The herbicide Agent Orange was also sprayed from the air to defoliate the forests that protected the Viet Cong and deprive them of food sources. A total of 90 million liters of herbicides were sprayed during the war, and because of their toxicity, they still cause cancer and mutations many years after they were used .

The development of the helicopter was particularly advanced during the Vietnam War. Troops could be easily transported by helicopter and dropped off in rough terrain. This made tactics possible in which first bombing was carried out from the air and then infantry could be released to fight the remaining resistance on the ground and to hold the position. In addition, the troops could easily be evacuated and withdraw. This also made dangerous parachute landings superfluous. At the same time, the helicopter reduced the time it took an injured US soldier to get to the hospital to seven minutes.

The best known was the Bell UH-1 "Huey", which is part of every background noise of the Vietnam War because of its popping rotor noise (nickname in the Bundeswehr is "carpet beater"). Here also helicopters were armed and used for combat missions. While the previous armament was intended more for self-defense, it now developed an offensive character. Although the Bell UH-1 is not an attack helicopter as it is today, it was able to transport additional machine weapons or rocket pods on pylons and thus became an improvised attack helicopter. With the Bell AH-1 , the first pure combat helicopter in the world was put into service by the USA, taking into account the first experiences in the Vietnam War. Combat helicopters are now highly mobile anti-tank means and are able to effectively provide close infantry support and carry out reconnaissance.

Second Gulf War

The Second Gulf War of 1991 was a military operation that, based on a UN resolution, aimed to liberate Iraq-occupied Kuwait. The war was decided largely by air operations carried out by the United States and its allies. More than 1,000 attacks were flown per day, and a greater load of weapons was dropped from the fighter planes during the course of the war than during the Second World War. The development continued that ground troops are only deployed when all targets that can be reached from the air have been destroyed.

The war was determined by the first use of satellite and computer-aided weapons systems, such as precision-guided bombs , stealth bombers and cruise missiles . Because of the heavy media coverage, the air war was presented by the Pentagon as a "cleaner" solution after the napalm bombing during the Vietnam War sparked fierce national and international criticism. The term “ surgical warfare ” was coined, but it turned out to be propaganda , as civilian casualties nonetheless occurred. B. in the attacks on the Iraqi positions by B-52 bombers, also numerous conventional weapons were used. The use of uranium ammunition in particular is proving to be devastating for the civilian population (see also: Gulf War Syndrome ).

Although the course of the war underscored the technological superiority of the USA and its allies , fatal errors had to be admitted in the area of friend-foe recognition , especially in the area of close support to the advancing ground forces.

21st century

In modern warfare, air sovereignty is achieved at the beginning of an operation to guarantee freedom of action over the area of operation, in order to then support one's own ground forces with targeted attacks on the enemy, enable airborne operations and attack strategic targets (infrastructure, industry).

The aerial warfare of the dawning 21st century is characterized by a strong transformation process . Many air forces, particularly those of the United States, the United Kingdom, and Israel, have learned over the course of several wars that the primacy of air superiority and initiative against asymmetrically acting opponents is of limited use.

The war in Kosovo , the war in Afghanistan , the Iraq war and the Lebanon war in 2006 made it clear that essential war goals such as ending alleged genocide , apprehending terrorists , finding weapons of mass destruction or freeing soldiers from enemy control cannot be achieved by air strikes alone . Although war aircraft can reach any place on earth through aerial refueling and aircraft carriers and prepare for the deployment of ground troops, they cannot replace them.

While Enthauptungsschläge ( "decapitation strikes", attacking the leadership structures of the opponent) rarely reach their destination, numerous collateral damage bring the war from the air at the edge of their Legitimierbarkeit. Although the central planning of an air war is retained, the implementation is increasingly decentralized. This takes place within the framework of networked combat management , with the help of which the communication channels are greatly shortened.

See also

- Aerial combat maneuvers

- Air surveillance

- Military aviation

- Single-jet aircraft (with classification according to area of application, dimensions and production)

- Twin-engine aircraft (with classification according to area of application, dimensions and production)

- Three-jet aircraft (with classification according to area of application, dimensions and production)

- Four-engine aircraft (with classification according to area of application, dimensions and production)

- Six-engine aircraft (with classification according to area of application, dimensions and production)

- Eight-engine aircraft (with classification according to area of application, dimensions and production)

literature

- Gebhard Aders : Bomb War. Strategies of Destruction 1939–1945. LiCo, Bergisch Gladbach 2004, ISBN 3-937490-90-6 .

- Martin Albrecht, Helga Radau: Stalag Luft I in Barth. British and American prisoners of war in Pomerania 1940 to 1945. Thomas Helms Verlag Schwerin 2012. ISBN 978-3-940207-70-8 .

- Jörg Arnold / Dietmar Süß / Malte Thiessen (eds.): Air war. Memories in Germany and Europe. Wallstein, Göttingen 2009, ISBN 978-3-8353-0541-0 (Contributions to the history of the 20th century 10).

- Eberhard Birk , Heiner Möllers (eds.): Luftwaffe und Luftwaffe (= writings on the history of the German Air Force. Volume 3) Hartmann, Miles-Verlag, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-937885-93-3 .

- Ralf Blank : Battle of the Ruhr. The Ruhr area in the war year 1943. Klartext, Essen 2013, ISBN 978-3-8375-0078-3 .

- Ralf Blank: Hagen in the Second World War. Bomb warfare, everyday war life and armaments in a Westphalian city. Essen 2008, ISBN 978-3-8375-0009-7 .

- Ralf Blank: Everyday life in the war and aerial warfare on the “home front”. In: The German Reich and the Second World War . Volume 9/1: The German War Society 1939–1945. Half Volume 1: Politicization, Annihilation, Survival. Ed .: Military History Research Office , Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt , Munich 2004, ISBN 3-421-06236-6 , pp. 357-461.

- Ralf Blank: The end of the war on the Rhine and Ruhr 1944/1945. In: Bernd-A. Rusinek (Ed.): End of the war 1945. Crimes, catastrophes, liberations from a national and international perspective. Wallstein-Verlag, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-89244-793-4 .

- Ralf Blank: Strategic aerial warfare against Germany 1914–1918. In: Clio-Online (Topic Portal First World War), 2004 ( PDF ).

- Hans-Joachim Blankenburg / Günther Sinncker: Air War over Central Thuringia 1944–1945. Rockstuhl, Bad Langensalza 2007, ISBN 978-3-938997-52-9 .

- Horst Boog (ed.): Air warfare in the Second World War. An international comparison. Mittler, Herford / Bonn 1993, ISBN 3-8132-0340-9 .

- Horst Boog: Strategic Air War in Europe 1943–1944 / 45. In: The German Reich and the Second World War. Volume 7: The German Reich on the defensive. Strategic Air War in Europe, War in the West and East Asia 1943–1944 / 45. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-421-05507-6 .

- Friedhelm Brack: When fire fell from the sky. On the trail of the air war from 1939 to 1945 in the Bergisches Land and Rhineland. Books On Demand GmbH, Norderstedt 2000, ISBN 3-8311-2718-2 .

- Federal Minister for Expellees, Refugees and War Victims: The Air War over Germany 1939–1945. German reports and press comments from neutral foreign countries. dtv documents, Munich 1964.

- Stephan Burgdorff, Christian Habbe (ed.): When fire fell from the sky. The bombing war in Germany. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-421-05755-9 .

- Alan Cooper: Air Battle of the Ruhr. Airlife Publishing, 1992, ISBN 1-85310-201-6 .

- Helmuth Euler : When Germany's dams broke. The truth about the bombing of the Möhne-Eder-Sorpe dams in 1943. Motorbuch, Stuttgart 1975, ISBN 3-87943-367-4 .

- Georg W. Feuchter: History of the air war. Development and future. Athenaeum, Bonn 1954; 3rd edition under the title Der Luftkrieg. Athenaeum, Frankfurt / Bonn 1964.

- Roger A. Freeman: The Mighty Eighth War Diary. Jane's Publishing, London 1981, ISBN 0-7106-0038-0 .

- Holger Frerichs: The bombing war in Friesland 1939 to 1945. A documentation of the damage and victims in the area of the Friesland district. 3rd edition, Lührs, Jever 2002, ISBN 3-00-002189-2 .

- Jörg Friedrich : The fire. Germany in the bombing war 1940–1945. Propylaea, Berlin, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-549-07165-5 . ( Review notes on Perlentaucher )

- Lothar Fritze: The moral of bomb terror. Allied area bombing in World War II. Olzog, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-7892-8191-4 . ( Klaus Hildebrand : Adolfs Fear and Winstons Rage. Review. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . August 4, 2007)

- Werner Girbig: 1000 days over Germany. The 8th American Air Force in World War II. Lehmann, Munich 1964.

-

AC Grayling : Among the Dead Cities . The History and Moral Legacy of the WWII Bombing of Civilians in Germany and Japan. London 2006, ISBN 0-7475-7671-8 .

- German edition: The dead cities. Were the Allied bombing war crimes? Bertelsmann, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-570-00845-4 .

- Otmar Gotterbarm: When the enemies fell from the sky. 1944 between Federsee and Alb. Zeitgut, Berlin, ISBN 3-933336-50-3 .

- Siegfried Gräff : Death in an air attack Results of pathological-anatomical investigations on the occasion of the attacks on Hamburg in the years 1943 - 1945 , HH Nölke Verlag, Hamburg 1948, http://d-nb.info/451634675 .

- Olaf Groehler : History of the Air War. 1910 to 1980. Military publishing house of the German Democratic Republic, Berlin 1975 (8th edition 1990, ISBN 3-327-00218-5 ).

- Nina Grontzki, Gerd Niewerth, Rolf Potthoff (eds.): When the stones caught fire. The bombing war in the Ruhr area. Memories. Klartext, Essen 2003, ISBN 3-89861-208-2 .

- Eckart Grote: Target Brunswick 1943-1945. Air raid target Braunschweig, documents of destruction. Heitefuss, Braunschweig 1994, ISBN 3-9803243-2-X .

- Frank Güth, Axel Paul, Horst Schuh: Not returned from the enemy flight. The fate of aviators in the Eifel, Rhine and Moselle regions. A documentation. Ed. AG Luftkriegsgeschichte Rheinland. Helios, Aachen 2001, ISBN 3-933608-33-3 .

- Frank Güth, Axel Paul: Objective: Survive! The fate of German and Allied aviators between 1914–1945 in the Eifel, Rhine and Moselle regions and other regions. Helios, Aachen 2003, ISBN 3-933608-75-9 .

- Ian L. Hawkins: The Munster Raid. Before and After. 3rd edition, Food & Nutrition, 1999, ISBN 0-917678-49-4 .

- German partial edition: Münster, October 10, 1943. Allied and German fighter pilots and those affected in the city describe the terrible events during the air raid. Aschendorff, Münster 1983, ISBN 3-402-05200-8 .

- Peter Hinchliffe: The other battle. Air Force night aces versus Bomber Command. Airlife, 1996, ISBN 1-85310-547-3 .

- German edition: Aerial warfare at night 1939–1945. Motorbuch, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-613-01861-6 .

- Thomas Hippler, translated by Daniel Fastner: The Government of Heaven. Global history of aerial warfare . Matthes & Sitz, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-95757-336-0 .

- Bernd Kasten: April 7, 1943. Bombs on Schwerin. Thomas Helms Verlag Schwerin 2013, ISBN 978-3-940207-93-7 .

- Norbert Krüger: The air raids on Essen 1940-1945. A documentation. In: Essen contributions. Volume 113. Klartext, Essen 2001, ISBN 3-89861-068-3 .

- Heinz Meyer: Air raids between the North Sea, Harz and Heide. A documentation of the bombing and deep attacks in words and pictures 1939-1945. Sünteltal, Hameln 1983, ISBN 3-9800912-0-1 .

- Martin Middlebrook: The Nuremberg raid. 30-31 March 1944. Fontana / Collins, 1974, ISBN 0-00-633625-6 .

- German edition: The night the bombers died. The attack on Nuremberg and its consequences for the aerial warfare. Ullstein, Frankfurt / Berlin / Vienna 1975, ISBN 3-550-07315-1 .

- Martin Middlebrook, Chris Everitt: The Bomber Command war diaries. An operational reference book, 1939-1945. Midland, Leicester 1996, ISBN 1-85780-033-8 .

- Christian Möller: The operations of night battle groups 1, 2 and 20 on the Western Front from September 1944 to May 1945. With an overview of the formation and use of the disturbance and night battle groups of the German Air Force from 1942 to 1944. Helios, Aachen 2008, ISBN 978- 3-938208-67-0 .

- Rolf-Dieter Müller: The bombing war 1939-1945. Links, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-86153-317-0 .

-

Williamson Murray : Was in the air 1914-1945. Cassell, London 1999, ISBN 0-304-35223-3 .

- German edition: The Air War from 1914–1945. Brandenburgisches Verlags-Haus, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-89488-131-3 .

- Robin Neillands: The bomber was. Arthur Harris and the Allied bomber offensive, 1939-1945. Emphasis. Murray, London 2001, ISBN 0-7195-5637-6 .

- German edition: The war of the bombers. Arthur Harris and the Allied bomber offensive 1939–1945. Edition q, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-86124-547-7 .

-

Richard Overy : The Bombing War. Europe 1939-1945. Allen Lane, London 2013, ISBN 978-0-7139-9561-9 .

- German edition: The bombing war. Europe 1939–1945. Rowohlt, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-87134-782-5 .

- Gerald Penz: The Austro-Hungarian Air Force on the Carnic Front 1915–1917. Lecture at the symposium of Arbos - Society for Music and Theater. Nötsch-Arnoldstein 2007.

- Gerald Penz: Kuk airfields in and near Villach. Lecture at the symposium of Arbos - Society for Music and Theater, Villach 2008.

- Janusz Piekalkiewicz: Air War. 1939-1945. Südwest, Munich 1978, ISBN 3-517-00605-X . (New edition: Heyne, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-453-01502-9 )

- Rudolf Prescher : The red rooster over Braunschweig. Air raid protection measures and aerial warfare events in the city of Braunschweig 1927 to 1945. Orphanage printing house, Braunschweig 1955. 2nd edition: Pfankuch, Braunschweig 1994.

- Alfred Price: Battle Over The Reich. Ian Allan Publishing, 1973. New edition in two volumes: Battle Over The Reich. The Strategic Bomber Offensive Against Germany 1939-1945. Volume 1: August 1939-October 1943. 2006, ISBN 1-903223-47-4 ; Volume 2: November 1943-May 1945. 2006, ISBN 1-903223-48-2 .

- German edition: Air battle over Germany. Motorbuch, Stuttgart 1973, ISBN 3-87943-354-2 .

- Peter Schneider: Spies in the sky. Allied aerial photos in the Wittgenstein area during and after the Second World War. Thiele & Schwarz, 1996, ISBN 3-87816-092-5 .

- Ewald Schoof: The attack by American associations on Diepholz Air Base. A documentation of the deployment order No. 228. Heldt, Twistringen 2002.

- Ernst Stilla: The Air Force in the fight for air supremacy. Dissertation. University of Bonn 2005 ( online , PDF).

- Ralf Steckert: Exciting suffering. On the media staging of the “brand” and its historical and political impact in the run-up to the Second Iraq War, publication series “Culture - Education - Society”, edited by T. Köhler u. Lutz Hieber, Stuttgart: ibidem, 2008, ISBN 978-3-89821-910-5 .

- Dietmar Süß : Death from the air. War society and aerial warfare in Germany and England. Siedler, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-88680-932-5 .

- Matthias Thömmes: Death in the Eifel sky - aerial warfare over the Eifel 1939–1945. 4th edition, Helios, Aachen 2004, ISBN 3-933608-04-X .

- Doris Tillmann; Johannes Rosenplänter: Air War and "Home Front". War experience in the Nazi society in Kiel 1929-1945 . Solivagus-Verlag, Kiel 2020, ISBN 978-3-947064-09-0 .

- Walter Waiss: From the Boelcke archive. Volume 4: Chronicle of Kampfgeschwader No. 27 Boelcke, Part 3: 1.1.42–31.12.42. Helios, Aachen 2005, ISBN 3-938208-07-4 .

Web links

- The allied bombing war 1939–1945 on historicum.net , portal with many individual articles

- Battle of the Ruhr 1939–1945 , detailed documentation on the website of the Historisches Centrum Hagen

- Terror against terror? , from GEO Magazin , No. 02/03 ( Crimes against the Germans? )

- The paradigm shift in aerial warfare by Friedrich Korkisch, Austrian Military Journal , issue 5/2002

- Dietmar Süß: "Home Front" and "People's War": New literature on the history of the aerial warfare (review essay on current research trends on aerial warfare at the Institute for Contemporary History Munich-Berlin)

-

The Air Campaigns (overview / list of links, English)

- Office of Air Force History - United States Air Force (Ed.): 1986: The Strategic Air War Against Germany and Japan: A Memoir (295 pages)

- History of the Air War: (When the plane lost its innocence - the first years of the Air War 1914-1918)

- Online video: Berlin in November 1943 after a night bomb attack (13 min.)

- Sven Lindquist: "Fire freely on the wild!" In Le Monde diplomatique, edition of March 15, 2002

- Death from the Air Spiegel Online Einestages, May 8, 2015 edition

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hague Land Warfare Regulations : Article 25, Geneva Agreement : Article 51 of Additional Protocol I: (Additional Protocol to the Geneva Agreement of August 12, 1949 on the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflict), original , accessed on August 19, 2016

- ↑ Equipping tomorrow's military and civilian leaders to tackle emerging security challenges at nps.edu.

- ^ Daniel Moran: Geography and Strategy. In: John Baylis et al. a .: Contemporary Strategy. 2nd edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2007, p. 133.

- ↑ Harenberg compact dictionary. Volume 2. Harenberg, ISBN 3-611-00542-8 , p. 1843.

- ^ Manfried Rauchsteiner , Manfred Litscher (Ed.): The Army History Museum in Vienna. Vienna, 2000, p. 43.

- ^ Christian Ortner : The Austro-Hungarian Artillery from 1867 to 1918. Technology, organization and combat methods. Vienna 2007, p. 73.

- ↑ 20 minutes from 13./14. May 2011: The very first bomb fell on Libya

- ↑ Il primo utilizzo bellico della forza aerea. In: aeronautica.difesa.it. Retrieved May 4, 2019 (Italian).

- ^ Gerhard Wiechmann: The Prussian-German Navy in Latin America 1866 - 1914: a study of German gunboat policy. Dissertation, University of Oldenburg, 2000. Pages 366–367. ( online ).

- ↑ See Holger H. Herwig: The Marne, 1914. The Opening of World War I and the Battle That Changed the World. New York 2011, p. 110; Reichsarchiv (ed.): The border battles in the west (The World War 1914 to 1918, Volume 1). Berlin 1925, p. 115.

- ↑ http://www.luftfahrtarchiv-koeln.de/ , entry '5. August 1914 '

- ^ Name from list of casualties in the Air Force 1914–1918. queried on December 23, 2009.

- ^ Dover in World War 1 Bombing and Shelling. ( Memento of June 3, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) accessed on December 23, 2009.

- ^ New York Times of December 25, 1914: German air raider drops bomb in Dover. ( Memento of December 27, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Retrieved June 16, 2019.

- ^ RJ Wyatt: Death from the Skies. The Zeppelin Raids over Norfolk 19 January 1915. Gliddon Books, Norwich 1990, ISBN 0-947893-17-2 .

- ↑ www.zeppelin-museum.dk ( Memento from June 8, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ see also Norman LR Franks, Frank W. Bailey: Over the front: a complete record of the fighter aces and units of the United States and French Air Services, 1914-1918. Grub Street, 1992. ISBN 978-0-948817-54-0 .

- ^ Neugebauer, Ostertag: Fundamentals of German military history. Volume 2: Work and source book. Rombach, Freiburg 1993, p. 209.

- ↑ Rudibert Kunz: The gas war against the Rif-Kabylen in Spanish-Morocco 1922-1927. In: Genocide and War Crimes in the First Half of the 20th Century. Edited by Fritz Bauer Institute, Campus-Verlag, 2004, ISBN 3-593-37282-7 .

- ^ Klaus A. Maier: The destruction of Gernika on April 26, 1937. In: Military history. Historical Education Journal. Issue 1/2007, pp. 18-22, ISSN 0940-4163 , Online PDF 2,180 kB (entire issue), here p. 22.

- ^ Marian Zgorniak Europa am Abgrund , 2002, p. 57, ISBN 3-8258-6062-0 digitalisat

- ↑ Der Spiegel, April 1, 2003

- ↑ Heinz Guderian: memories of a soldier. 18th edition, Motorbuch, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-87943-693-2 .

- ↑ a b Detlef Vogel: Operation criminal court. The ruthless bombing of Belgrade by the German air force on April 6, 1941. In: Gerd R. Ueberschär , Wolfram Wette (Ed.): War crimes in the 20th century. Primus, Darmstadt 2001, ISBN 3-89678-417-X .

- ↑ Transcript of the speech under the heading We are equipped for every case in: Freiburger Zeitung of December 11, 1940 , p. 9, bottom, middle

- ↑ 1786 Air Force operations against England in one day - documentary film Minute 19:10

- ↑ BBC article 70 years later on the firestorm in the City of London in 1940 (English)

- ^ Rolf-Dieter Müller : The bombing war 1939-1945. Links Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-86153-317-0 , p. 86.

- ^ Documentary film Stalingrad; Minute 6:20 to the air raids before the storm on the city ( page no longer available , search in web archives )

- ↑ 60 Years End of the War - Topics ( Memento from June 4, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ www.raf.mod.uk - Thousand Bomber raids ( Memento from August 27, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (English)

- ↑ Original film of the United States Army Air Forces about the use of four squadrons of the 8th Air Fleet; Minute 25:30

- ↑ Michael Foedrowitz: Bunker Worlds: Air Defense Systems in Northern Germany. Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-89555-062-0 , p. 115 ff.

- ↑ Exhibition commemorates the year 70 after the bombs. www.welt.de, October 3, 2013.

- ↑ Katharina Stegelmann: Bombing war in Berlin: Death from heaven. www.spiegel.de, October 10, 2012.

- ↑ Markus Scholz: Development of radio measurement technology

- ↑ This is considered to be the third firestorm of World War II; previously, London in 1940 and Lübeck in 1942 were affected.

- ^ Siegfried Gräff: Death in an air raid , HH Nölke Verlag Hamburg 1948 [1]

- ^ Hansjakob Stehle: "The spies from the rectory" , Zeit.de, January 5, 1996, accessed on October 10, 2018

- ↑ Peter Broucek: The Austrian Identity in the Resistance 1938-1945. In: Military resistance: studies on the Austrian state sentiment and Nazi defense. Böhlau Verlag , 2008, p. 163 , accessed on August 3, 2017 .

- ↑ Andrea Hurton, Hans Schafranek: In the network of traitors. In: derStandard.at . June 4, 2010. Retrieved August 3, 2017 . ; Peter Pirker "Subversion of German rule. The British secret service SOE and Austria" (2012), p. 252 ff.

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler in a review in the program The political book on Deutschlandradio. ( Memento from March 6, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Hans Mommsen: Moral, Strategic, Destructive. In: Lothar Kettenacker (Ed.): A people of victims? The new debate about the bombing war 1940-1945. Berlin 2003, p. 147.

- ↑ "Allies wanted this blood toll." Merkur-online , February 10, 2005.

- ^ Office of Air Force History - United States Air Force (ed.): The Strategic Air War Against Germany and Japan: A Memoir. 1986, p. 115 f.

- ^ BH Liddell Hart: History of the Second World War. Perigree Books, New York 1982, p. 691.

- ^ Janusz Piekałkiewicz : The Second World War. ECON Verlag, 1985, ISBN 3-89350-544-X .

- ↑ Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star. In: aviation-history.com. Retrieved February 28, 2015 .

- ^ Napalm over North Korea. In: taz.de . December 10, 2004, accessed February 28, 2015 .