Operation Rolling Thunder

| date | March 2, 1965 to November 1, 1968 |

|---|---|

| place | Democratic Republic of Vietnam , Kingdom of Laos |

| output | American strategy failed |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

William Westmoreland |

|

| losses | |

|

|

|

Vietnam War

Battle of Tua Hai (1960) - Battle of Ap Bac (1963) - Battle of Nam Dong (1964) - Tonkin Incident (1964) - Operation Flaming Dart (1965) - Operation Rolling Thunder (1965-68) - Battle of Dong Xoai (1965) - Battle of the Ia Drang Valley (1965) - Operation Crimp (1966) - Operation Hastings (1966) - Battle of Long Tan (1966) - Operation Attleboro (1966) - Operation Cedar Falls (1967) - Battle around Hill 881 (1967) - Battle of Dak To (1967) - Battle of Khe Sanh (1968) - Tet Offensive (1968) - Battle of Huế (1968) - Operation Speedy Express (1968/69) - Operation Dewey Canyon ( 1969) - Battle of Hamburger Hill (1969) - Operation MENU (1969/70) - Operation Lam Son 719 (1971) - Battle of FSB Mary Ann (1971) - Battle of Quảng Trị (1972) - Operation Linebacker (1972) - Operation Linebacker II (1972) - Battle of Xuan Loc (1975) - Operation Frequent Wind (1975)

Operation Rolling Thunder (German: Rollender Donner) was the first major air offensive by the American and South Vietnamese air forces against targets in North Vietnam and Laos . The bombing of selected targets was intended to halt the infiltration of North Vietnamese soldiers into the south, destroy the country's economic and military power, instill confidence in the Saigon regime and force Hanoi to accept American terms.

Initially, the attacks were concentrated on targets in the immediate vicinity of the demilitarized zone, but gradually moved north over the course of 1966. The so-called Hồ Chí Minh path in Laos was also gradually bombed more and more. The military use of the bombing is controversial, as North Vietnam was an agrarian country that had hardly any industry worth mentioning. Although there were practically no relevant targets left in mid-1966, the Americans stuck to the air offensive. However, the Republic of Vietnam managed to limit the damage at home and maintain tactical initiative. After the Tet offensive , the air offensive was canceled. The USA and North Vietnam had meanwhile agreed on negotiations, although there was still no real willingness to compromise on either side.

Previous course of the war

escalation

In the course of 1964, the National People's Liberation Front (NLF) and the North Vietnamese People's Army increasingly succeeded in gaining control over South Vietnam . Despite massive American military and economic aid, the situation for the South Vietnamese regime became increasingly hopeless. During some major battles, such as those at Binh Gia, Dong Xoai and Ba Gia, the insurgents won several victories over units of the ARVN . American military advisors were also increasingly the target of attacks, such as B. during the bomb attacks on the Saigon Capitol or the Hotel Brink, in February 1965 their number was already 23,300. But despite all efforts, the regime was on the brink of collapse militarily. The ground troops of the ARVN were mainly busy protecting innumerable bridges, city entrances, economic objects, villages and roads. Meanwhile, their casualties amounted to almost 12,000 men a month, lost to death, wounding or desertion. Politically, too, the country was almost at an end. After the coup against Ngo Dinh Diem in 1963, Saigon failed to form a stable government recognized by the people. On February 18, 1965, the three young generals Nguyễn Cao Kỳ, Nguyễn Văn Thiệu and Nguyễn Chánh Thi took power without bloodshed. This was the eighth putsch of the officer corps after Diệm's death on November 3, 1963.

Beginning of the air raids

Up to this point in time, the Americans had largely refrained from air strikes against North Vietnam. The actions against the country were mainly limited to a few acts of sabotage by the Americans and South Vietnamese organized by the CIA, leaflets and secret air surveillance. But secretly, detailed plans for the bombing of North Vietnam have already begun. Numerous high-ranking military officials have long been calling for an extensive air campaign in order, according to Air Force General Curtis E. LeMay , to “ bomb North Vietnam back into the Stone Age” and to remove any basis from the alleged invasion hit by the American bombardment in Laos. But the events in the Gulf of Tonkin in early August 1964 provided Washington with a welcome opportunity to demonstrate its resolve in Hanoi. There, on the afternoon of August 2, the American destroyer Maddox was attacked by North Vietnamese torpedo boats ( Tonkin incident ). The ship was on a reconnaissance voyage to observe enemy radar systems. The day before, there were several attacks against plants on the North Vietnamese islands of Hòn Mê and Hòn Ngư . The leaders in Washington were well aware of what prompted the North Vietnamese to attack. Still, President Johnson's incident was publicly classified as a military provocation. Instead of withdrawing the ship, Washington sought the confrontation and ordered the destroyer Turner Joy to the scene. On the night of August 4, both ships reported enemy fire and returned fire. For this reason the American leaders decided to launch the first open air raids on North Vietnam. A few other reports referring to unfavorable weather conditions and possibly incorrect radar reports were simply ignored. On August 5, US 7th Fleet bombers rose to attack North Vietnamese naval bases and fuel depots.

There was a very long discussion about what was going on in the Gulf of Tonkin at that time. But after years of research, it can now be confirmed with certainty that there never was a second North Vietnamese attack. Although the Americans did not prepare for the incident well in advance, it served as an excuse to finally begin the long-planned air strikes. On August 7th, the infamous 'Gulf of Tonkin Resolution', drafted weeks earlier, passed the Congress without a dissenting vote. This resolution authorized President Johnson "to take all necessary measures to repel the attacks and prevent future aggression." The American attacks on the islands that had been carried out shortly before the incidents were wisely kept secret from the representatives of the people. With some senators worried about the vague wording and the sweeping nature of the resolution, Johnson assured him that he would not abuse the political trust placed in him. But very soon the resolution no longer formed a parliamentary sanctioned basis, solely for isolated actions, but served as a justification and justification for American war policy as a whole. With it the dispatch of hundreds of thousands of soldiers and the devastation of North and South Vietnam were justified. Nicholas Katzenbach , who was Undersecretary of State in the State Department , aptly described the resolution as the "functional equivalent of a declaration of war".

But despite the resolution and the urging of the high military, there were initially no attacks against North Vietnam. Unlike many of his advisors, Johnson did not steer lightly towards war with North Vietnam. But in the months that followed, the situation in South Vietnam became increasingly chaotic and the Allies came under increasing pressure. On February 7, 1965, the NLF attacked an American helicopter base near Plei Cu in the central highlands. At 2:00 a.m., the base suddenly came under mortar fire. In the chaos that followed, some fuel depots exploded and 11 helicopters and airplanes were destroyed by explosive charges. Eight Americans were killed and 128 injured. A few days before the attack, the still undecided President Johnson dispatched his security adviser McGeorge Bundy to Saigon. When the latter found out about the attack, he and General Maxwell Taylor went to General William Westmoreland's headquarters , telephoned the White House and recommended retaliatory attacks on North Vietnam. On the afternoon of February 7, during Operation Flaming Dart , 45 fighter-bombers from the aircraft carriers Hancock , Coral Sea and Ranger flew attacks on North Vietnamese barracks near Dong Hoi, above the DMZ. An A-4C fighter was shot down during the operation and the North Vietnamese Army announced that it was able to recover the body of pilot Edward A. Dickson.

Three days later, 23 American advisors were killed and 21 wounded in an NLF bombing of American accommodation near Quy Nhơn . In the course of these developments, Johnson ordered the start of an unlimited air offensive against North Vietnam. The Operation Rolling Thunder began. As in August last year, the US government avoided fully informing the population about the consequences of the developments. Government spokesmen downplayed the decisions and assured them that the air strikes were only retaliatory acts in response to Hanoi's aggression. The fact that the operation did not involve isolated retaliatory strikes but was an air offensive without a time limit was not admitted.

The aerial war over North Vietnam and Laos

Rolling thunder

The American Commander in Chief in the Pacific, Admiral Ulysses S. Grant Sharp, called for the first large-scale air strikes on February 20. However, due to unrest in Saigon, the attacks were postponed until March 2nd. The delays frustrated Sharp and were the first of countless disagreements to come between the top military in Saigon on the one hand and civilian decision-makers in Washington on the other. From the beginning there were different opinions about how the air campaign should be carried out. President Johnson shrank from the air before the total destruction of North Vietnam. The risk of a possible Chinese or even Soviet intervention was too high. In early April 1965, the Chinese Foreign Minister Zhōu Ēnlái sent a message to President Johnson. It said China did not want to start a war with the United States, but if it did, Beijing would be prepared. The US will not be able to withdraw, and no bombing policy will change that. "We would stand up without hesitation and fight to the end ... Once the war has broken out, there will be no borders."

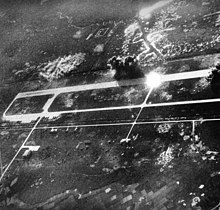

For this reason, the American administration created a sophisticated rating system with the help of which supposedly important military targets in North Vietnam were selected for bombing. Each target list was passed through a complex chain of command once or twice a week to the Department of Defense , State Department , White House, and often the President himself. These could determine the strength, direction and even altitude of the attacks. First and foremost, the air strikes should be of psychological importance. They should break the will of Hanoi and force them to accept the conditions dictated by the Americans. “The nature of the attacks was designed to keep the options open, whether to continue them or not, to escalate or not, to increase the speed or not, depending on how North Vietnam reacts. The carrot of stopping the bombing was as important as the stick of continuation, and bombing kept that balance. ”The military, however, weren't too happy with this type of warfare. The combined Chiefs of Staff and the commanders of the Army , Navy and Air Force wanted to carry out the attacks with great severity. They wanted to bomb North Vietnam continuously and with overwhelming force, destroy its airfields, power plants, military bases and air defenses, shut down its underdeveloped industries and cut the country off from supplies of foreign fuel and supplies. Instead, however, they had to adhere to a large number of restrictions and restrictions. The doctrine of single target selection and gradual escalation took precedence. The pilots and also many generals saw this policy as dangerous and militarily pointless. American fighter pilot Jack Broughton once said, "We have consistently killed our most experienced pilots and lost expensive and irreplaceable aircraft because of the maze of restrictions placed on those who had to fight in this impossible situation." Operation Rolling Thunder was expanded step by step. The attack radius of the air strikes moved further and further north from the 17th parallel. During this time, a number of bridges, ammunition depots, arms factories, power plants, train stations, barracks, fuel depots, naval bases and radar systems fell victim to the air offensive. The number of attacks was gradually increased to 900 per week for a total of 55,000 per year. American fighter bombers rose from their bases in South Vietnam, Okinawa , Guam and the aircraft carriers in the South China Sea to attack, in which they dropped a total of 63,000 tons of bombs on North Vietnam and Laos in 1965. But the larger industrial centers in Hanoi and the port facilities of Hải Phòng were spared the attacks for the time being. The same was true for a strip of territory 25 miles apart along the Chinese border. In late March, the Joint Chiefs of Staff drafted a 12-week plan of attack aimed at bringing North Vietnam to its knees. In this plan it was intended that the rail and road connections south of the 20th parallel should first be systematically shut down. After that, over the course of several weeks, all traffic connections between North Vietnam and China were to be destroyed. In the next step, the port facilities would be made unusable in order to cut off the land from the sea. After all, the plan was to continue attacking factories in sparsely populated areas until the North Vietnamese leadership realized that the next targets would be the industrial centers in Hanoi and Hải Phong. But neither Johnson nor Defense Secretary Robert McNamara were ready to cause a major escalation, they did not want to give up control of the air offensive.

Meanwhile, the war in South Vietnam was spiraling out of control. Although the air campaign over North Vietnam had strengthened the morale of the Saigon regime, or so they told the Americans, in spite of all this, the ARVN was on the verge of collapse in the summer of 1965. After General Westmoreland requested marines at the end of February, two battalions of the US Marine Corps equipped with tanks and artillery landed on Da Nang beach on March 8, 1965, and were greeted by some Vietnamese women with wreaths of flowers. By the end of the year there should be 184,000 US soldiers. It became increasingly clear, however, that the bombardment of North Vietnam had no significant impact on the war in the south. At the same time, Johnson's advisors and senior military officials urged the air campaign to be stepped up. President Johnson partially bowed to the pressure. Some previously spared goals such as B. the railway bridges to China have been released for destruction. But the North Vietnamese were prepared for these developments. Until well into 1968, the Americans had little idea of their enemy. Contrary to all predictions and calculations, the North Vietnamese should be able to withstand the attacks and continue the invasion of South Vietnam without any apparent difficulty.

Democratic Republic of Vietnam

North Vietnam was a country at war at the time. By mobilizing the entire population for the resistance struggle and also with Chinese and Soviet support, Hanoi managed to keep the material damage in its own country within limits. The population of the large cities was evacuated, and the first major resettlement campaigns began as early as 1965. In Hanoi and other cities, trenches and fragmentation trenches were dug before the air raids began, and the population was trained in regular air defense exercises. Schools, hospitals, ministries, administrative offices and some armaments and industrial plants were moved to inaccessible areas or underground. As in the south of the country, an extensive and complex tunnel system over 40,000 km long ran through the areas hardest hit by the air raids. The secondary schools were closed and the pupils or students were assigned to air raid units, drafted into the militia or the army, or sent as auxiliary workers in agriculture and the armaments industry. By mid-1966, Hanoi was already deserted by more than 70% of the population. In the beginning the air raids occasionally caused panic among the population, but after a short time the people appeared to be more disciplined. Loudspeaker trucks drove through the streets every day and announced the locations of the incoming American bombers. A secretary of the French delegation in Hanoi reported: “Everything is almost eerily silent. Life dies all of a sudden. Cars are parked on the roadside, shops are closed and people disappear from the sidewalks, and after a few minutes soldiers and air raiders are patrolling the deserted city. Only noisy loudspeakers announce the targets and the number of aircraft shot down. It's a picture like that of George Orwell. "

The entire population was drawn into the government's war effort. More than 100,000 farmers were assigned to build roads to the Laotian border and the Truong Son Road (Ho Chi Minh Trail). Many of them performed porter services for the North Vietnamese People's Army. The country's women had often taken their place; by 1967 they made up two thirds of all those employed in agriculture. 250–300,000 people worked day and night in 'voluntary work units' to clean up the bomb damage. Entire divisions worked, especially between Hanoi and Haiphong and in the region around Vinh, repairing roads, bridges and railways, usually at night, with enormous effort. “We are now living for the next day and do not know when, where and where the next bomb will fall. But we live and as long as we live, we can work and fight, ”said an employee of the North Vietnamese embassy in Vientiane , the Laotian capital.

Foreign support

The massive support of its two powerful allies was also of great importance to the country's stamina. As early as June 1964, Mao Zedong told the North Vietnamese chief of staff, General Văn Tiến Dũng: “Our two parties and countries must work together and fight the enemy together. Your worries are my worries and my worries are your worries ... we must face the enemy together and unconditionally. ”During the next few months, further negotiations between the countries took place. On May 16, 1965, Ho Chi Minh met with Mao Zedong to discuss further plans. The leader of the DRV asked for help in upgrading the road systems in Laos and north of Hanoi. Mao agreed. A month later, General Văn Tiến Dũng met with the Chinese General Staff. They coordinated further actions, including the eventual dispatch of regular troops of the Chinese People's Army to Vietnam. The generals agreed on the deployment of logistics and engineering troops to restore the infrastructure of North Vietnam and enable the country to stand up to the United States.

Shortly afterwards, the 1st Division of the Chinese People's Liberation Army Volunteer Forces entered the country. This unit consisted of 6 regiments, which were supported by 2 more until 1968. First, the Chinese built numerous railway bridges and routes along the Red River valley towards Hanoi. By 1966, the small town of Yen Bay, not far from the Chinese border, had been expanded into a huge logistics complex. Over the next few years, the volunteer army built 14 tunnels, 39 bridges, 20 train stations, 70 miles of new route and countless anti-aircraft positions. On June 6th, the 2nd Division followed, consisting of 3 regiments, a hydrological regiment, a water transport unit, a transport regiment, a communication unit and several air defense units. In total, the Chinese sent around 320,000 soldiers to North Vietnam, who were mainly used in the construction of dykes, bridges, roads and railways and in air defense. In addition, the North Vietnamese received around $ 460 million in economic and military aid by the end of 1964 alone. It mainly comprised uniforms, weapons, ammunition, consumer goods, vehicles and food. In addition, China supplied agricultural machinery, set up light industries, model farms, an iron combine and plants for rice processing. Beijing spent millions of dollars on propaganda campaigns in North Vietnam, including school books and propaganda materials.

The Soviet aid up to this point was also by no means to be underestimated. The Soviet Union built until 1966 more than 10 power stations, 30 light alloy factories and canneries for Hải Phòng, chemical plants for Thái Nguyên , Lâm Thao and Việt Trì and a machine factory for Hanoi. Between 1954 and 1964 it granted the DRV loans totaling approximately $ 500 million. In addition, they primarily supplied North Vietnam with handguns, including from East German production. However, Moscow refused to deliver heavy military equipment as requested by North Vietnam. By the end of 1964, relations between the countries deteriorated noticeably. But then in the winter of 1964/65 a new leadership came to power in Moscow. Concerned about the Chinese dominance in Southeast Asia, a resumption of political relations with the DRV and the Liberation Front in South Vietnam began.

On February 7, 1965, a fateful event occurred in North Vietnam. At that time, a Soviet delegation visited Hanoi, including Prime Minister Alexei Kosygin. The delegation was on its way to Beijing to start new talks with Mao Zedong and was warmly welcomed by the North Vietnamese. Then, while the Soviet delegation was in Hanoi, the NLF suddenly attacked the helicopter base at Pleiku. Before President Johnson could understand the consequences of his decisions, he ordered the first air strikes on Hanoi. Moscow outraged that the very first air strikes on Hanoi were carried out while high-ranking Soviet officials were there. The Soviet Ambassador to Washington, Anatoly Dobrynin, said: “Kosygin was very angry about the fact that the bombing took place while he was in Vietnam and turned against Johnson, although he had generally been positive about him in previous meetings in the Kremlin Shortly after the air strikes, Dean Rusk rushed to Dobrynin and assured him that the attacks only targeted Hanoi and not the Soviet Union. However, these words fell on deaf ears. On the same day in Hanoi an aid agreement was signed between the two countries that provided for the delivery of modern Soviet weapons technology and support from military advisers. But despite the enormous importance of military and economic aid, the two allies were unable to gain any significant political influence over Hanoi. The North Vietnamese managed to successfully play off Moscow and Beijing against each other. In contrast to most of the other Eastern Bloc countries, the DRV retained its full independence. It is not without reason that the North Vietnamese were characterized by the Soviet Union as alien and “narrow-minded national”.

The air defense of the country

Foreign aid was particularly important in relation to the anti-aircraft systems in North Vietnam. In early 1965, there were very few guns there that could do anything against the attackers. This led to the notorious movement 'Rifles against Airplanes' among the population, in which the civilian population was trained with simple rifles in the fight against bombers. It was not until August and September 1965 that the movement, which at times assumed hysterical proportions, was disbanded. Between April and June 1965 the military situation changed dramatically. General Phùng Thế Tài was appointed commander in chief of the anti-aircraft troops . In April, the first Soviet surface-to-air missile positions were established near Hanoi. On July 24th, the first American airplane was destroyed by rocket fire. From that day on, a secret war between the Soviet Union and the United States was fought in Vietnam. The People's Army had no soldiers who could cope with the technical complexity of anti-aircraft missiles . Therefore, it took a while for the North Vietnamese crews to be trained. During this time, Soviet soldiers took over the operation of the anti-aircraft missile positions. One of the commanders of the Soviet anti-aircraft troops in the DRV was Colonel G. Lubinitzki. He himself shot down 3 American planes and a drone. In addition, his battalion was able to record 23 hits with a consumption of 45 missiles. “The most impressive moment,” recalled Sergeant Kolesnik, “was when the planes went down. All of a sudden, an object that you could not even see before was transformed into a glow of burning debris in the middle of the darkness. The American commanders pressed At first Johnson hesitated, but when the first plane was shot down, he authorized air strikes to focus on the missile positions. The Americans used electronic means to trick the missile radar. The Soviets Forces, in turn, built fake missile missiles to mislead the Americans.

The Chinese also made up a large proportion of all anti-aircraft troops in the DRV. Following inquiries from the NVA General Staff, the 61st and 63rd anti-aircraft divisions of the Chinese People's Army entered North Vietnam on August 1, 1965. In the same month, both divisions began fighting at Yên Bái and Kep, a base of the North Vietnamese Air Force. Even if the air defense systems of the NVA were often the target of various other air campaigns, they were never able to eliminate a really large proportion of the cannon and missile positions. Over time, the effectiveness of air defense increased more and more. Soviet radars, computerized anti-aircraft guns, surface-to-air missiles and interceptor squadrons resulted in heavy losses on the part of the American armed forces. While the Americans only lost 171 aircraft in 1965, there were already 318 in 1966. 161,000 tons of bombs were dropped on North Vietnam alone during this time without any significant effect. In the meantime, the American commanders became more and more nervous because none of the goals set could be achieved. It was not possible to break the will of Hanoi, nor could the flow of soldiers and supplies over the so-called Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos be interrupted. Because while North Vietnam was being bombed more and more, Laos had become the scene of a war of its own.

War over Laos

Countless attempts had been made by mid-1966 to effectively disrupt Truong Son Road (known in the west as the Ho Chi Minh Path). The first actions against the trail were taken in late 1963, when Lao Air Force fighter jets began bombing North Vietnamese camps in Laos. The first targets were the cities of Mường Phìn, Xépôn and Muang Nong, which were occupied by units of the North Vietnamese People's Army and Pathet Lao . The air strikes were gradually expanded, but had no noticeable effect. In order to get a better picture of what was going on in the Laotian border area, armed reconnaissance patrols were sent out for the first time in mid-1964. The first of these operations was code-named 'Leaping Lena'. Originally there should be two Americans and four Vietnamese in a team, but in the end they consisted of 8 exclusively Vietnamese soldiers. The Leaping Lena teams were given the task of monitoring the assigned area for more than a month, but that never happened. One team disappeared and was never seen again. Contact was temporarily maintained with the other teams. But numerous other soldiers were captured or disappeared without a trace. In total, only 5 men returned. 'Leaping Lena' is a good example of many upcoming missions by American or South Vietnamese special forces, which often enough ended in the loss of entire command trains.

The command of the path in Laos was Colonel (later General) Võ Bẩm, a supply specialist from the Ministry of Defense. As early as May 1959 he was given the task of "creating a military communication line to send supplies for the revolution to the south and to expand them if possible." After initially only a few rifles and some personnel were transported to the south, they were impassable After a few years, paths should be expanded to truck width and paved. In May 1959, Group 559 was also formed, an initially secret unit that was responsible for the logistical work and the repair of the path. After the Americans began bombarding the transport system on a large scale, command was transferred to General Phan Trọng Tuệ on the orders of General Võ Nguyên Giáp . He was also responsible for the anti-aircraft troops in Laos. They were supported by units of the Pathet Lao, the Laotian equivalent of the Liberation Front in South Vietnam.

In late 1964, the war finally escalated and the Americans began bombing targets in Laos. On December 14th, 15 aircraft of the American Air Force flew their first missions, three days later the Navy carried out further attacks. The same targets were bombed in these air strikes as almost two years earlier. The city of Xépôn, as an important replenishment base and transit station, was one of the main targets of the air campaign from the start. For the first time, American scouts spotted larger truck convoys - a naval pilot saw 8 to 10 vehicles in one convoy, the next 16 to 20. In the period that followed, there were numerous different campaigns to finally bring traffic to a standstill, many of which failed. For example, 'Project Hardnose', a CIA company to better monitor traffic. The project had to be canceled after a short time after the two commanding CIA officers were killed in a helicopter crash. Operation Steel Tiger was a major aerial campaign that began in late 1964. Despite the ongoing bombing, there was no noticeable effect on the transport along the path. Inadequate information from the secret service led to some misunderstandings and misguided attacks, in which some Laotian soldiers and civilians were killed in May 1965. As a result of protests by Laotian government officials, Operation Steel Tiger had to be temporarily suspended. In the next few months, the Americans focused on some bottlenecks and mountain trails such as B. those at Mụ Giạ and Napé. But despite the initial use of B-52 bombers and cluster bombs, no breakthrough could be achieved here either.

During the last three months of 1965 more than 4,000 attacks were carried out as part of the Steel Tiger. During January and February 1966 there were already 12,000 and another 5,000 in the following month. Even so, according to official figures, only 100 trucks were destroyed and 115 more damaged. After 'Steel Tiger' did not bring the hoped-for success, 'Operation Tiger Hound' was initiated. The aim of this operation was to combine the missions of reconnaissance and combat aircraft in order to enable a faster deployment. Light machines such as the Q-1 Cessna delivered the information directly to the combat aircraft, which enabled them to maneuver much faster. In fact, some successes were achieved, so the stakes were expanded. However, Operation Tiger Hound also suffered a major setback when, on March 15, Lt. Col. David H. Holmes, one of the leading officers in the operation, was shot down over Laos.

According to American sources, the US air campaign in 1966 was extremely successful. About 58,000 sorties were flown over Laos, plus 129,000 over North Vietnam. A total of 52,000 tons of explosives were thrown over Laos and 123,000 tons on the DRV. Statistics say that 2,067 vehicles were destroyed (2,017 damaged), 1,095 railways and freight cars (1,219 damaged) and 3,690 boats (5,810 damaged) in that year alone. 489 American planes were lost over Laos and North Vietnam by the end of 1966. Nevertheless, the unimaginable for everyone involved happened. North Vietnam was still on the rise. Because although almost 200,000 sorties have now been flown, not even 20% of the North Vietnamese military and economic power had been destroyed. In view of the facts, there was nothing for President Johnson to do but accept a further escalation of the war.

The POL campaign

At the beginning of 1966, most of the military were still convinced that the lack of results was mainly due to the fragmentation of American clout and the many restrictions. Pacific Commander Admiral Ulysses Sharp spoke to many officers when he said in late 1965: "The United States Armed Forces should not be required to wage this war with one arm tied behind their back." Following the recommendations of the military, Johnson had to consider the reports of the CIA. These emphasized that North Vietnam was primarily an agricultural country, with a primitive transport system and little industry. Almost all of the equipment came from China or the Soviet Union. The fighters of the Liberation Front and the NVA in the south only needed a very small amount of supplies from the north, about 100 tons per day. Seen in this light, North Vietnam was hardly a worthwhile target for air strikes; there were simply not enough bomb targets.

Then, in the spring of 1966, there were calls for a new aerial campaign that would finally bring noticeable success. An attack on the oil and fuel reserves of the north (petrolium, oil and lubricants- POL). The joint chiefs of staff declared that an attack on the oil depots would be "a more devastating blow against the transport of war material within the People's Republic of Vietnam and via the supply routes to South Vietnam than an attack on any other target group". 79% of all fuels were concentrated in only 13 cities, 60% were needed for the military alone each year. The trucks and motorized boats that hauled supplies south would not run without fuel. The security advisor of President Walt W. Rostow was very optimistic. Defense Secretary McNamara was reluctant to agree, as reports from the CIA weeks before had questioned the success of such air strikes. Nevertheless, the strikes could be carried out without causing massive damage to the port facilities or causing great civilian casualties. Despite some concerns, President Johnson agreed on June 22nd. The attacks were to be carried out with great effort and only the most experienced teams were allowed to participate. All aircraft were also supported by other machines to suppress anti-aircraft missiles and avoid target acquisition by surface-to-air missiles. Clear and sunny weather was necessary, so the military command in Vietnam McNamara sent weather reports every few hours from June 24th. On June 29th the time had come. From Washington the order to carry out was sent to Admiral Sharp. Hundreds of planes took off for North Vietnam from Thailand , South Vietnam and the aircraft carriers in the South China Sea. The fuel depots in Hanoi and Hải Phong were attacked simultaneously, and by the end of the day the sky over both cities was covered with smoke and fire. The tremors of the explosions could still be felt hundreds of kilometers away. By the end of the month, nearly 80% of all fuel reserves in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam had been destroyed. Thanks to extensive evacuation measures, the number of civilian victims was very low, and only one man is said to have died in the attack on the fuel depot in Hải Phong. The 7th American Air Force in Saigon described the operation as "the most significant and important blow of the war". The international criticism of the attacks was limited; McNamara also described the attacks as “excellent work” and congratulated those involved. It was statistically the most successful aerial campaign of the war.

In fact, however, it could have absolutely no influence on the course of the war. Despite the destruction of most of their reserves, North Vietnam was never short of fuel. The population and the military did not need these large amounts anyway. Their needs could be satisfied by a system of smaller fuel stores that were hidden along the path, in underground hiding places or in the dense rainforest. The bombing devastated the port of Hải Phong, but the tankers simply docked in front of the coast and filled the fuel in tons. The infiltration of people and material via the path in Laos continued unabated. In addition, the NVA was prepared for the attacks. They moved some of their anti-aircraft systems close to the fuel reserves and inflicted considerable losses on the American reconnaissance squadrons, only one fighter-bomber was shot down during the actual attacks. In late September, the CIA and DIA concluded that there was "no evidence of any shortage of fuel in North Vietnam ... no evidence of significant transportation difficulties ... no economic shift and no weakening of public morale." further American aerial campaign proved a failure.

Contradiction, opposition and failure

US peace initiatives

While the American military puzzled over how North Vietnam could finally be brought to its knees, dissatisfaction with the war grew. The spectacle of the world's most powerful military machine waging war against one of the poorest countries on earth caused a huge storm of protest. In every peace initiative and every attempt at mediation by the Americans, public opinion in the United States and the Western world should be positively influenced and reassured. Johnson campaigned for a negotiated peace three months before regular associations were sent to Vietnam. Between 1965 and the end of 1967 there were a total of 2,000 mediation attempts by diplomats, private individuals and politicians. But the president still hoped for a promising turn in the war, so he had no real interest in a war that did not end with the total subjugation of the north.

In January 1966 the American administration published the so-called "Fourteen Point Program" with which the government wanted to show its willingness to negotiate. But this initiative also reflected the tactical considerations of the Americans: the USA declared itself ready to end the air campaign after the North Vietnamese engagement in South Vietnam. In addition, the Americans would withdraw from the country if a satisfactory political solution was found. The interests of the NLF wanted to be taken into account, but a coalition government was out of the question. Johnson also offered the North reparations for all damage caused and still to be caused by the bombing. The offer was received with scorn and ridicule by the North Vietnamese. Critics rightly described the offer of talks as a barely veiled ultimatum. Less than a year later, Johnson ordered particularly violent attacks on targets in the DRV, thus undoing preliminary talks that a Polish diplomat was trying to thread. A few months later, in February 1967, he snubbed America's closest ally, Great Britain , when he undermined attempts at mediation initiated by British and Soviet Prime Ministers Harold Wilson and Alexei Kosygin . North Vietnam was not to be forced into confessions through negotiations, but solely through bombs.

During 1967, however, public pressure on Johnson increased. Given the dwindling support for his policies and the ongoing fighting in South Vietnam, the president changed his previously adamant stance. In the 'San Antonio Formula' published in September 1967, he declared that the US would be ready to end the air war if Hanoi agreed to constructive negotiations. Beyond that, there should be no further infiltration into the south. He approved of the liberation front a political role in South Vietnam after the war. In reality, however, Johnson was still hoping to defeat North Vietnam or the NLF. Hanoi didn't even respond to the 'San Antonio Formula'. Because there was just as little a serious will to compromise on the North Vietnamese side. Despite significant victories on the battlefield, there had been two defeats at the negotiating table in the past - in 1946, between the end of World War II and the beginning of the First Indochina War, and 1954, when Mao Zedong took the Việt Minh to accept the American Conditions had urged. There shouldn't be another political defeat. The North Vietnamese motto could only be: negotiate and keep fighting. The two sides faced each other irreconcilably at the end of 1967. North Vietnamese and American ideas were still mutually exclusive.

Cessation of air attacks

The failure of the POL campaign convinced many Americans that the bombardment of North Vietnam could never have any significant impact on the war in the south. Most far-reaching, however, was Robert McNamara's increasing disenchantment and disillusionment. Deeply disappointed with the failure of the campaign, he drew the attention of Navy and Air Force commanders to the deep gulf that existed between the hopeful predictions of success and reports prior to the start of the attacks and the fact that the attacks had had no discernible effect. It gradually became clear to him that the aerial warfare was not a suitable means of stopping the infiltration, of breaking the will of Hanoi, or even of achieving an end to the war that was favorable to the USA. He also increasingly realized that the predictions of the CIA were correct in every respect and that the military, contrary to all announcements, saw no way to end the war. In October of the same year he reported to the President: “In order to bomb the north effectively, in order to bring about a radical cut in Hanoi's political, economic and social structure, we would have to make an effort that would be entirely possible, but which was neither our own nor ours would be put up with by the world's people and would put us at serious risk of engaging in war with China ... I guess it is best to keep the bombardment at this level ... and when the time comes, we should consider pull to stop the air strikes completely or at least in the north-eastern border areas, in connection with further steps towards peace. ”Many Americans, including those still hoping for a victory, had come to realize that the air campaign was probably more one An obstacle than an aid to achieve an acceptable end to the war. Harrison Salisbury, a renowned correspondent for the New York Times , visited North Vietnam around the turn of 1966/67. His reports barely matched the United States Department of Defense statements that all targets attacked were military installations. He reported on the suffering of the population and how numerous cities were literally razed to the ground. Meanwhile, McNamara had become an opponent of American war policy. In May 1967 he realized: "The image of the greatest superpower in the world, killing or seriously wounding 1,000 civilians a week to force a small, backward country to give way to a highly controversial goal, is not a beautiful one." But none of the military leaders was ready to even consider discontinuing the air campaign. In her opinion, the only wrong thing about the attacks was that they were too gradual and too limited. The Senate Armed Forces Committee , which represented the faction willing to escalate, was of the same opinion . Members were the experienced political leader Senator John C. Stennis and other senators who had always advocated a military escalation. The members of the Stennis Committee, as well as the generals and officers of the armed forces, knew very little about Vietnam, but they did know something about the possibilities of air war and how it could influence armed conflict. They had seen with their own eyes the destruction this had brought over Japanese and German cities, remembered how the two largest Japanese bases in the Pacific had been isolated and destroyed by air strikes alone, and how the Wehrmacht's transport system in France was in front of the D. -Day had been smashed by air strikes. In disbelief, they listened to McNamara's arguments that the bombardment had destroyed practically all militarily and economically relevant targets in North Vietnam, but was still unable to stop the flow of fighters and material to the south. The opposite had happened: since the start of the attacks, the Communists had doubled their troops in the south. The chiefs of staff have already been given permission to bomb 85% of all targets. The limited importance of the 57 remaining targets, which were mainly in densely populated and heavily defended areas, does not justify the risk of further American casualties or a direct confrontation with the Soviet Union or China. Concerning Hanoi, McNamara remarked: "Their concerns for the well-being or the lives of their people are not high enough to force them to admit under the threat of further attacks."

As was to be expected, McNamara failed to convince the committee. Instead of listening to him, the members prepared a message to Johnson advising him to escalate again: “The fact that the air campaign did not meet its objectives as expected cannot be attributed to the incompetence of the air force. Rather, it is evidence that the fragmentation of our armed forces, the limitations and the doctrine of 'gradual escalation' imposed on our reconnaissance forces have prevented us from carrying out the campaign in the manner that might produce the best results. “Johnson eventually bowed to pressure from the military and the Stennis Committee and authorized attacks on 52 of the 57 remaining targets. By the end of 1967 nearly 99% of all targets in North Vietnam had been destroyed and yet there was no sign that the country would give in to American pressure.

Then, however, on January 31, 1968, the Tet Offensive took place , which was to shake the foundations of South Vietnam and America. In the morning, at 2:45 a.m. sharp, 80,000 guerrillas suddenly appeared openly and attacked 5 of the 6 large cities, 36 of the 44 provincial capitals, 64 local administrative offices and numerous localities. After weeks of fighting, the US troops and the ARVN succeeded in repelling the attacks and conquering areas in which no American had set foot for a long time. Militarily, the Allies had won a great victory. But the Vietnam War was far from just a conventional war. Politically speaking, the offensive was a slap in the face for Washington. Two months earlier, General Westmoreland had given a speech to both Houses of Congress that the progress was irreversible and that the enemy would soon be defeated. The Tet Offensive had overnight exposed these arguments as wishful thinking.

In February 1968, McNamara resigned and accepted his appointment as head of the World Bank. Given the ongoing fighting in Vietnam and the massive demonstrations in cities around the world, Johnson looked for a way out. On March 20 and 22, he met with his advisers to discuss the possibility of a bomb stop. But while some advocated the suspension of the air campaign, the chiefs of staff defended Westmoreland's plan to send an additional 206,000 men to Vietnam. Ultimately, the parties involved could not agree on any uniform measures. In order to finally be able to come to a decision, Johnson convened a meeting of the so-called 'wise men' on March 26, 1968. It was an informal circle of respected civil servants who, although they had no real power, had a lot of prestige and immense influence. Members included former Undersecretary George Ball, Secretary of Defense Cyrus Vance, Secretary of State Dean Acheson and three former Joint Chiefs of Staff. Johnson still hoped to get approval for his policy there. But this time numerous reasons spoke against an unchanged course: the surprising Tet Offensive, the pressure of the anti-war movement, the deep rift within the Democratic Party, the growing resistance of Congress, the dwindling support of the government in its own and the world public and concern influential circles on Wall Street about America's position in the world economic system. The message of the 'wise men' was to show the public that the US was not sinking deeper and deeper into war.

At 9 p.m. on Saturday, March 31, 1968, the President made a dramatic televised address to the American nation. “Good evening America. Tonight I want to talk to you about peace in Vietnam ... "After repeating the 'San Antonio formula', he said," I will take the first step to de-escalate the conflict. We are prepared to move immediately towards peace talks ... We will reduce the current level of hostilities - drastically reduce them. And we will do it without reservation and immediately. Tonight I gave orders to our air and naval forces not to launch any further attacks on North Vietnam, except in the areas immediately above the demarcation line, where the continued build-up of enemy troops is directly endangering the advanced Allied positions and where their movements are directly related to that threat. As in the past, the United States stands ready to send its representatives anytime, anywhere in the world to discuss measures to bring this ugly war to an end. I have chosen one of the most experienced Americans, Ambassador Averell Harriman, to be my personal representative for the talks. I appeal to President Ho Chi Minh to follow this new step towards peace ... With America's sons on battlefields far away, with the challenges of Americans here at home, with our hopes and the world's hopes for peace, I believe not that I should spend even an hour of my time doing any unimportant business or other duty unrelated to the enormous duties of this post - the presidency of your country. Therefore, I will not request or accept any further nominations from my party for the office of president. "

Three days later the unexpected happened for everyone, the North Vietnamese reacted positively to Johnson's speech. On April 3, Radio Hanoi announced that North Vietnam was ready "to send its representatives to contact the American representatives and to achieve an unconditional cessation of the bombing and all acts of war against the DRV, so that the peace talks can begin." On November 30th, Johnson finally announced, after discussions with his advisors, that all air, sea and artillery fire would cease and that peace talks could begin a week later. But despite the negotiations, withdrawal was out of the question for the American administration. Since the areas north of the 20th parallel were already covered with mist and fog during the months of the monsoon, the cessation of the air attacks was of no military importance. Instead, operations against areas under NLF control tripled during the year. The air campaign was only resumed on April 4, 1972, as part of the Easter offensive.

Losses and numbers

Operation Rolling Thunder was one of the largest aerial campaigns ever carried out. From March 1965 to December 1967, more than 864,000 tons of explosives were dropped on North Vietnam and Laos, far more than twice as much as over the entire Pacific during World War II. According to American sources, by October 22, 1968, 99% of the targets proposed by the chiefs of staff had been destroyed. This includes 77% of all ammunition stores, 65% of all fuel stores, 59% of all power plants, 55% of all bridges and 39% of all train stations in North Vietnam. The country had only one large cement, iron, and explosives factory at a time, and all of them were destroyed. In addition, 12,521 large and small ships, 9,821 vehicles and 1,966 railways and freight wagons were destroyed and thousands more damaged. However, it must be taken into account that these figures are US data and many of them did not correspond to reality. There is no precise information about the victims in North Vietnam in the course of the air campaign. Hanoi itself never published exact figures and the American figures were very vague. It speaks of around 52,000 civilian and 20,000 military victims. However, since there have been countless reports of civilians killed and injured by both Americans and North Vietnamese, there were probably tens of thousands of victims.

Regardless of how many casualties the air war actually claimed, it definitely had not achieved its goals. After initial difficulties, Hanoi managed to mobilize almost the entire population for the war. Despite the great destruction, the air raids did not seriously affect North Vietnam's ability to continue the war. The transport of people and material on the Ho Chi Minh Trail increased continuously despite many disabilities. Thanks to foreign aid, the air defense systems have been massively strengthened and modernized. By the end of 1968, the Americans had lost 938 aircraft valued at over $ 6 billion, but in return the damage was the equivalent of $ 600 million. The efficiency analyzes ordered by McNamara also came to the conclusion that a total of 9.6 dollars was used to cause property damage of just one dollar in North Vietnam. 835 pilots were either killed, captured, or missing. The prisoners were to prove to be an important bargaining chip for Hanoi in later negotiations. The fact that the North Vietnamese had American prisoners was a particular thorn in the side of the Washington administration. The air war sparked the protests of the opponents of the war, who accused the government of crimes against humanity and made it increasingly difficult to explain. The terror from the air welded the people of North Vietnam together. Instead of weakening the country, he strengthened the cohesion of North Vietnamese society.

literature

- Kuno Knöbl: Victor Charlie: Viet Cong - The uncanny enemy . 4th edition. Heyne Verlag , Munich 1968.

- Ronald Spector: After Tet: The Bloodiest Year in Vietnam . 1st edition. The Free Press, New York 1993, ISBN 978-0-02-930380-1 .

- Marc Frey : History of the Vietnam War . The tragedy in Asia and the end of the American dream. 9th edition. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-61035-6 .

- John Prados: The Blood Road . The Ho Chi Minh Trail and the Vietnam War. 1st edition. Wiley, New York 2000, ISBN 978-0-471-37945-4 .

- Guenter Lewy: America in Vietnam . Oxford University Press, New York 1980, ISBN 978-0-19-502732-7 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Lewy: America in Vietnam. 1980, p. 405

- ↑ Frey: History of the Vietnam War. 2010, p. 118

- ↑ Frey: History of the Vietnam War. 2010, p. 115

- ↑ Frey: History of the Vietnam War. 2010, p. 104

- ↑ Frey: History of the Vietnam War. 2010, p. 105

- ↑ Frey: History of the Vietnam War. 2010, p. 117

- ^ Prados: The Blood Road. 2000, p. 95

- ↑ Frey: History of the Vietnam War. 2010, p. 105

- ^ Prados: The Blood Road. 2000, p. 96

- ^ Prados: The Blood Road. 2000, p. 124

- ↑ Spector: After Tet: The Bloodiest Year in Vietnam. 1993, p. 12

- ↑ Spector: After Tet: The Bloodiest Year in Vietnam. 1993, pp. 12-13

- ↑ Spector: After Tet: The Bloodiest Year in Vietnam. 1993, p. 13

- ↑ Frey: History of the Vietnam War. 2010, p. 127

- ↑ Sheehen: The Pentagon Papers , pp 394

- ^ Lewy: America in Vietnam. 1980, p. 379

- ↑ Knöbl: Victor Charlie: Viet Cong - The uncanny enemy. 1968, p. 255

- ↑ Knöbl: Victor Charlie: Viet Cong - The uncanny enemy. 1968, p. 256

- ↑ Frey: History of the Vietnam War. 2010, p. 128

- ↑ Knöbl: Victor Charlie: Viet Cong - The uncanny enemy. 1968, p. 257

- ^ Prados: The Blood Road. 2000, p. 124

- ^ Prados: The Blood Road. 2000, p. 125

- ↑ Frey: History of the Vietnam War. 2010, p. 105

- ↑ Knöbl: Victor Charlie: Viet Cong - The uncanny enemy. 1968, p. 251

- ^ Prados: The Blood Road. 2000, pp. 131-132

- ↑ Frey: History of the Vietnam War. 2010, p. 114

- ↑ Knöbl: Victor Charlie: Viet Cong - The uncanny enemy. 1968, p. 256

- ^ Prados: The Blood Road. 2000, p. 133

- ^ Prados: The Blood Road. 2000, p. 88

- ^ Prados: The Blood Road. 2000, p. 83

- ^ Prados: The Blood Road. 2000, p. 9

- ^ Prados: The Blood Road. 2000, p. 156

- ^ Prados: The Blood Road. 2000, p. 163

- ↑ Spector: After Tet: The Bloodiest Year in Vietnam. 1993, p. 16

- ↑ Frey: History of the Vietnam War. 2010, p. 148

- ↑ Frey: History of the Vietnam War. 2010, p. 122

- ↑ Spector: After Tet: The Bloodiest Year in Vietnam. 1993, p. 17

- ↑ Frey: History of the Vietnam War. 2010, p. 127

- ^ Lewy: America in Vietnam. 1980, p. 384

- ↑ Frey: History of the Vietnam War. 2010, p. 172

- ↑ Spector: After Tet: The Bloodiest Year in Vietnam. 1993, p. 22

- ↑ Spector: After Tet: The Bloodiest Year in Vietnam. 1993, pp. 22-23

- ^ Lewy: America in Vietnam. 1980, p. 387

- ^ Lewy: America in Vietnam. 1980, p. 390