Operation Lam Son 719

| date | February 8 to March 24, 1971 |

|---|---|

| place | Southeast Laos (Sepone District, Savannakhet Province ) |

| output | Victory of the North Vietnamese People's Army |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Hoàng Xuân Lãm |

|

| Troop strength | |

|

36,000 soldiers, 3 infantry divisions, 3 infantry regiments, 8 artillery regiments, 3 engineer regiments, 3 tank battalions, 6 anti-aircraft battalions , 8 assault pioneer battalions (more than 33 battalions in total) |

20,000 soldiers, 1 infantry division, 1 tank brigade, 2 marine infantry brigades, 3 paratrooper brigades, 3 ranger battalions, 1 engineer battalion, several helicopter squadrons and artillery divisions (a total of 22 battalions) 10,000 soldiers, various support troops , reconnaissance, bomber and helicopter crews - and artillery units |

| losses | |

|

|

|

Vietnam War

Battle of Tua Hai (1960) - Battle of Ap Bac (1963) - Battle of Nam Dong (1964) - Tonkin Incident (1964) - Operation Flaming Dart (1965) - Operation Rolling Thunder (1965-68) - Battle of Dong Xoai (1965) - Battle of the Ia Drang Valley (1965) - Operation Crimp (1966) - Operation Hastings (1966) - Battle of Long Tan (1966) - Operation Attleboro (1966) - Operation Cedar Falls (1967) - Battle around Hill 881 (1967) - Battle of Dak To (1967) - Battle of Khe Sanh (1968) - Tet Offensive (1968) - Battle of Huế (1968) - Operation Speedy Express (1968/69) - Operation Dewey Canyon ( 1969) - Battle of Hamburger Hill (1969) - Operation MENU (1969/70) - Operation Lam Son 719 (1971) - Battle of FSB Mary Ann (1971) - Battle of Quảng Trị (1972) - Operation Linebacker (1972) - Operation Linebacker II (1972) - Battle of Xuan Loc (1975) - Operation Frequent Wind (1975)

Operation Lam Son 719 ( Vietnamese Chiến dịch Lam Sơn 719 ) was an offensive of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) during the Vietnam War in the South Vietnamese - Lao border area . It began on February 8 and ended on March 24, 1971. The military goal was to destroy the supply routes of the North Vietnamese army in southeast Laos via the Ho Chi Minh Trail . The political aim of the advance was to force North Vietnam to the negotiating table, to make the success of the " Vietnamization " of the war clear to the world public and to buy time for the Saigon regime.

To this end, more than 20,000 South Vietnamese soldiers crossed the borders with north-west Laos and captured the small town of Xépôn , about 30 km from the border , which was seen as the main target of the campaign. American ground troops were already banned from entering Laotian territory at that time due to a recently passed law. After initial successes, the troops of the ARVN got more and more distressed by the well-armed divisions of Hanoi . During the retreat, the soldiers were attacked with tanks and heavy artillery in their rear. The military leadership of the ARVN was completely overwhelmed by the surprising situation, only massive bombing by the American air force could prevent panic. The incursion into Laos was the worst defeat the ARVN had to cope with up to this point. The South Vietnamese regime had risked a lot and sent some of the best troops it could possibly have; the loss of these units would continue to have an impact until the Easter offensive of 1972 . In addition, the failure intensified the declining morale of the remaining US soldiers and the widespread questioning of American engagement in Vietnam.

background

planning

By the late 1960s, Truong Son Street (known in the West as Ho Chi Minh Path) had assumed a downright mythological character. Despite the heaviest bombing in human history, the invasions in Laos and Cambodia (early 1969 and May 1970, respectively) and the expenditure of many billions of US dollars , it was not possible to prevent the flow of fighters and material to any significant extent. According to US intelligence agencies, between 1966 and 1971, 630,000 soldiers, 100,000 tons of food, 400,000 weapons and over 50,000 tons of ammunition came south from North Vietnam. In 1970 the complete withdrawal of all US armed forces became increasingly evident. In the face of fewer and fewer soldiers available, the military and political leadership came under pressure. In late 1970, Henry Kissinger , security advisor to President Richard Nixon , came to the conclusion that it was necessary to attack the North Vietnamese supply routes in Laos while there were still enough US troops available. Admiral John McCain , Lt. Gen. James Sutherland, and General Creighton Abrams agreed to this plan and on December 8, along with their staff, began planning for an upcoming invasion.

On December 12, Abrams finally presented his plan, he called it: "[...] a coordinated ground and air attack [...] to destroy the enemy supply lines at Xépôn [...] and give the enemy his logistical connection, which is necessary, to keep the war going. A force comprising several regiments will occupy the area around Xépôn , carry out operations within base camp 604 to destroy the enemy camps and facilities and interrupt the two major routes north and south of Xépôn . "The Supreme Military Command in Vietnam (MACV) reported briefly to Washington thereafter that a major disruption in supply routes during the dry season would reset North Vietnam's offensive power by at least a year, possibly even longer. A high-ranking American officer said after examining some reconnaissance photos: “ Xépôn and the base camps there have everything - cannons, trucks, fuel. If we marched in there and cleared the area, it would set them back a year, maybe two. We'd be crazy not to. "

Preparations

In December 1970, the so-called "Cooper Church Amendment" passed the United States Congress . This law precluded the stationing of American troops in Laos, Cambodia and Thailand and forced US troops to largely cease military aid to their Lao and Cambodian allies. It also followed that the impending invasion of Laos had to be carried out exclusively by ARVN troops. The Americans could only provide assistance with helicopters, bombers and artillery. From December 1970 to the final decision on January 18, 1971, President Nixon tried to counter the possible flare-up of a public protest storm. But this lost valuable planning time, which the ARVN absolutely needed to organize its largest, most important and most complicated mission to date.

In order to prevent the plans from falling into the hands of enemy agents, the entire planning was kept strictly confidential. Only a very limited number of officers knew about the operation. A press embargo was even imposed to prevent reporters from reporting on troop movements. But despite their best efforts, agents of the Liberation Front managed to get hold of the plans. A CIA report suggested that enemy informants infiltrated the translation and copying facilities at the Vietnamese headquarters and were thus able to obtain all of the operational plans. The result was that the North Vietnamese Army began to prepare for a defensive battle in mid-January. The press embargo was lifted on February 4th.

At the ARVN, however, the situation was completely different. The units involved did not receive any detailed orders until January 17th. In fact, the airborne division that was supposed to lead the attack wasn't notified until February 2, less than a week before the operation officially began. As a result, the ARVN troops did not have enough time to plan and prepare, and the ARVN staff did not work together to coordinate the attacks. The management staff of the ARVN itself also posed serious problems. Lieutenant General Hoàng Xuân Lãm, who was also the commander of the I. Corps (the five northernmost provinces of Vietnam), was chosen as the supreme commander of the South Vietnamese troops . General Lãm had a great deal of administrative and political influence, and he also knew how to influence people for his own purposes. But he did not have leadership skills. The main reason Lieutenant General Lãm was still chief of the I. Corps and even became the operation commander was President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu . Since Lãm was a close confidante of Thiệus, he hoped to make him a hero, to give him prestige and experience and thereby to be promoted to chief of staff . He was to replace General Cao Văn Viên, who had asked to resign.

Despite clear signs of inadequate planning and leadership, US and ARVN commanders became increasingly confident. Airborne Division advisor Colonel Arthur W. Pence reported during a meeting at XXIV Corps headquarters: “American intelligence has come to believe that the troops will encounter only slight resistance during the operation and that air strikes will take two days to prepare sufficient to effectively shut down the enemy anti-aircraft systems, since the enemy probably only has 170 to 200 anti-aircraft guns of various caliber in the area of operations. The danger posed by armored troops is minimal and support troops are only available about two divisions north of the DMZ (Demilitarized Zone) within 14 days. ”However, these intelligence information turned out to be largely incorrect. As it turned out, the only correct prediction concerned the support troops of the North Vietnamese People's Army (NVA). Even if they didn't have to march across the DMZ first, but were already stationed further south in the A Shau valley . Bad weather also prevented preparatory air strikes so that the enemy air defense positions were never attacked.

The South Vietnamese and American troops

To attack the enemy supply routes in Laos, the ARVN dispatched some of the best units it still had. The 1st Armored Brigade , the 1st Infantry Division (generally regarded as the best combat unit of the ARVN), the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Brigades of Paratroopers , the 147th and 258th Brigade of the Marines , the 39th, 37th and 21st Ranger Battalions, the 101st Combat Engineer Battalion and other helicopter troops. Each infantry regiment also had an artillery division . The troop strength totaled 20,000 men, about 22 battalions . However, the use of these elite units also involved a great deal of risk. The naval and paratrooper battalions were primarily battle-tested soldiers, many of whom were also involved in the invasion of Cambodia. Better paid, equipped and trained than almost all other ARVN associations, they supported regular units during important operations. At the same time, they formed the strategic reserve of the South Vietnamese Army, so it was necessary to keep their losses as low as possible. Their crucial importance was shown, among other things, in the fact that they did not receive their orders from commanders in the field, as usually, but only from the joint general staff and the President from Saigon . So far they had only fought as individual battalions or brigades and had little experience of working with other units.

Since no American ground troops were allowed to enter Laos, their support was mainly limited to transport, reconnaissance, security, logistics and air strikes against Laotian territory. The tactical commander of the US forces was Brigadier General John H. Hill. He served under General Sutherland, the commander of the XXIV Corps. He was subordinate to many different units, including two armored brigades, four infantry battalions, several artillery battalions and a ranger company. In addition, the experienced pilots of the 101st Airborne Division and some transport and engineering units of the Marines participated in the operation. Ultimately, reconnaissance, bomber and fighter aircraft of the Navy and Marines also made an important contribution to the implementation of the operation. Thus, the XXIV Corps commanded a total of around 10,000 soldiers.

Start of the operation

Dewey Canyon II

A week before the invasion of Laos, the Americans began the first part of their plan. At the beginning of Operation "Dewey Canyon II", the Khe Sanh Combat Base , which had been abandoned in mid-1968, was put back into operation. At this point, not a single American had set foot in the Khe Sanh area for months . American officers and soldiers expected a tough battle for the landing zones. In fact, however, there was no significant fighting; the American losses were very small. Preparatory air strikes on the surrounding area began at 8:30 a.m. and ended around noon. A complete battalion landed shortly afterwards in Khe Sanh and secured the orphaned airfield of the old base. Captain Doug McLeod was a doctor in 1st Battalion / 11th. Regiment. He was one of the first to enter the premises. He later told a journalist, "We thought we would have some kind of enemy contact - mortar fire or an assault by storm pioneers ('sapper')." But not a single North Vietnamese soldier showed up throughout the day. Only two bases at Mai Loc and the Fuller Fire Support Base were under fire. It wasn't until four days later that patrols came across a system of 40 to 50 abandoned bunkers near Lang Vei .

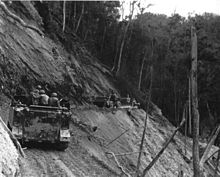

Another important task was the repair of road 9, which led towards Laos. Soldiers of the 7th, 14th and 27th Combat Engineer Battalions built several bridges and even a second path that ran north of Road 9. He enormously improved the accessibility and supply capacity of Khe Sanh and the other support bases. Equally important was the repair of the airfield in Khe Sanh, which enabled even heavy transport machines to land. But here too the first problems arose. Due to the delayed opening of the airfield and the insufficient carrying capacity of the transport helicopters, the fuel supply became more and more problematic. Americans' worries worsened when a convoy of numerous tank trucks was ambushed on Road 9 on February 8. In the attack at 2 a.m., six large tank trucks, each carrying 1200 gallons of fuel, were destroyed or severely damaged.

On January 29th, Lieutenant General Hoàng Xuân Lãm set up a previously presented headquarters in Dong Ha . At the same time the command post of the XXIV Corps was relocated to Quang Tri . The 1st Armored Brigade and 1st Infantry Division began to approach the Lao border via Road 9. To the west and northwest of Khe Sanh some fire support bases were set up to cover the attack. But even at this early stage, communication and organization should prove very difficult. For example, on the evening of February 6, there was a serious misunderstanding. At dusk, a naval pilot mistook an advanced ARVN post at the border for enemy troops. The plane dropped several cluster bombs. Six soldiers were killed, 51 others injured and an armored troop transport destroyed. Commenting on the incident, Lt. Col. Bui The Dung, one of the commanders, said: "It is tragic to lose men this way."

The incursion into Laos

On February 8, 1971 at 7:12 am, the South Vietnamese soldiers set foot on Laotian soil for the first time. The 4,000-strong column ahead consisted of the 1st Armored Brigade and units from the 1st and 8th Airborne Battalions. At the same time, the three ranger battalions and the 1st Infantry Division were deployed by helicopter north and south of Road 9. American artillery and B-52 bombers had already wreaked havoc in the area. At this point the soldiers were in a good mood. A paratrooper who had already participated in the invasion of Cambodia said mockingly, “Hey, this is the second time that we have gone to a foreign country without our passport.” But not all soldiers were so confident. One of the rangers said, "I've already fought in Cambodia and now I'm going to Laos ... I guess it will be tougher than Cambodia." A large red and white painted sign that reads "Warning - No US troops beyond this point." ! ”Confirmed this opinion.

The order of the large motorcade was to secure a 20 km long stretch to Ban Dong and then, with support, the remaining 20 km to Xépôn . But this task turned out to be more difficult than expected. The fear of ambushes in the thick rainforest on either side of the road slowed the convoy's progress, as did large bomb craters hidden from the reconnaissance planes by head-high grass and bamboo. Therefore the troops only advanced 9 km on the first day. The artillery behind the force gave support fire and moved with it at the same time. The 101st Combat Engineer Battalion of the ARVN cleared some parts of the road and built crossings at the places that were completely destroyed. But despite all the efforts of the engineers, the route remained impassable over long distances for trucks and off-road vehicles. This in turn made the units along Route 9 completely dependent on the American helicopters.

On the second day it began to rain, which finally brought the movement of the convoy to a complete standstill. On the third day it went on again. The first destination along the road was the small town of Ban Dong , which had also been a camp for North Vietnamese workers and soldiers. The plan provided that the paratroopers jumped over the city by helicopter and occupied the place together with armored troops. But due to the bad weather, it could only be implemented on February 10th. At 5 p.m., the 9th Airborne Battalion and the 1st Armored Brigade attacked and captured the city. But there was no trace of the enemy to be found. The workers in charge of the path (called Binh Trams ) and all the soldiers had withdrawn in perfect order with all their supplies. Up to this point the invading army had had practically no contact with the enemy, apart from sporadic sniper fire . At the same time as the attack on Ban Dong , the ARVN soldiers began to build bases on Laotian territory. Numerous landing zones were established north and south of Road 9, the 3rd Airborne Battalion and the headquarters of the 3rd Airborne Brigade occupied landing zone 31 without any contact with the enemy. There they set up the FSB (Fire Support Base) 31, with a battery of six 105 mm howitzers . Meanwhile, the 2nd Airborne Battalion set up FSB 30 with two batteries of 105 mm and 155 mm guns. In the next few days, more bases were built, including FSB Hotel, A Loui, Alpha, Delta, Delta I and others. On February 11th, all units of the 1st Armored Brigade were in position at Ban Dong and were waiting for further orders from General Lãm. But for more than three weeks nothing happened and the schedule got more and more out of hand. General Abrams urged to attack Xépôn as soon as possible. However, General Sutherland and General Viên and Lãm decided to build more FSBs south of Strait 9 to cover the advance of the airborne troops.

While the units were waiting for orders, they sent patrols to scout the area. In doing so, they encountered not only enemy troops, but also NVA supply stores. An FSB Ranger Nord patrol succeeded in confiscating two enemy 37 mm guns. During reconnaissance missions, units of the 1st Infantry Division encountered larger supply depots that housed weapons, ammunition, fuel, food and some corpses. The 3rd Airborne Battalion under Lieutenant Colonel Phat managed to capture six enemy trucks loaded with ammunition.

But despite these apparent successes, the military situation had already changed and began to turn against the ARVN troops. On a reconnaissance mission, Captain Frank Wickersham spotted enemy units near Xépôn and even south of Road 9. He was amazed at the amount of war material - tanks, trucks, artillery - almost too many to count. Obviously, this was just the prelude to a massive battle to come in Laos.

Counterattack

Reactions from North Vietnam

The North Vietnamese army was informed early on that the enemy was planning an offensive in Laos. It is not known exactly when their agents found out about this. In any case, General Lê Trọng Tấn, commander of the 70B Corps, began preparing his soldiers for a major battle as early as January. Fighters of the 24B Regiment of the 304th Division guarded Road 9 northeast of Ban Dong , while the 64th Regiment of the 320th Division lay ready south of the road. In Ban Dong itself, the local transport unit, the Binh Tram 33 , was alerted and was able to withdraw in good time. The 1st regiment of the 2nd Infantry Division was already on the way to Xépôn when the headquarters of the 70B Corps were moved to the combat area. On February 6th, the 1st regiment took up position near Ban Dong , while the 812th regiment of the 324B division was approaching from the south. On the day of the invasion, the NVA had already stationed 22,000 men nearby and more were to follow.

To distract the North Vietnamese from the invasion, units of the 9th Marine Brigade simulated a landing operation not far from the port city of Vinh . For five weeks they practiced the same maneuvers as would be necessary for an invasion of North Vietnam. Aircraft fired support for troops who were supposed to be landing, and helicopters took up positions as if they were picking up soldiers. The possibility of a landing at Vinh seemed real enough for Hanoi, some troops were moved from the DMZ to the area around Vinh .

The fall of the South Vietnamese bases

Real warfare could meanwhile be found in Laos. Little by little, the soldiers of the People's Army began to harass the enemy. First of all, the air defense systems were massively strengthened, making supplying the encircled bases more and more difficult. In the next step, the enemy fire support bases were covered with massive artillery, mortar and rocket fire , which caused the morale of the besieged soldiers to deteriorate. The North Vietnamese were able to play a trump card, because their 130 mm and 122 mm guns had a greater range than those of the ARVN. Since the soldiers of the NVA were often able to get very close to the enemy positions, supporting the FSBs with bombers and fighter planes was extremely risky. For example, B-52 bombers could only be used if allied troops were outside a 3 km wide security area. Even experienced commanders shied away from calling for tactical air support and artillery fire not far from their own units.

The first target of the North Vietnamese were the bases of the paratroopers and the rangers, north of the road 9. On February 18, the two bases Ranger North and Ranger South came under massive artillery fire, followed by infantry attacks. After a few attempts, the North Vietnamese soldiers from Ranger South left Ranger South for the time being and concentrated on Ranger North. With the help of fighter planes and artillery, they were able to hold the NVA troops there for two days. Several helicopters tried again and again to get to the trapped rangers, but heavy anti-aircraft fire prevented this. An American pilot described the devastated base: “The way it must have looked in Ranger Nord during World War II ... We flew a napalm attack less than 100 m from the ARVN troops. That was very close, we could see them in their trenches. ”On the afternoon of February 20, the remaining 300 rangers were surrounded by almost 2,000 soldiers from the 102nd regiment. With certain defeat in mind, the battalion commander decided to retreat towards Ranger South. The remaining soldiers had to carry their wounded comrades 6 km through the dense rainforest. From the initial 430 men, only 109 survivors reached the rescue base. The 39th Ranger Battalion was completely exhausted. Allegedly more than 600 NVA soldiers are said to have died in the fighting for Ranger Nord. Four days later, the FSB Ranger Süd also had to be abandoned. The effort to supply the warehouse was out of proportion to the strategic value. The 21st Ranger Battalion stationed there withdrew 5 km south to FSB 30, from where it was evacuated.

The rangers' defeat had far-reaching consequences in many ways. During the battle for Ranger Nord, some soldiers lost their nerve in the face of the hopeless situation. Many wanted to get out of Laos with the last helicopter, some clung to the helicopter's landing skids and escaped this way. When the machines reached Khe Sanh, they were photographed by television cameras and journalists. The sight of ARVN soldiers clinging to helicopter landing skids to escape the enemy became a lasting memory for many involved.

But of even greater significance was an event that took place hundreds of kilometers away. With the loss of the two ranger bases and the poor organization of the operation, President Thiệu became all too aware of General Lãm's ineptitude. In order to be able to give the operation a positive turnaround, Lãm should be relieved of his command and replaced by Lieutenant General Đỗ Cao Trí. General Trí was possibly the best commander the ARVN ever had. He had already proven himself in many battles and had now become something of a hero. After receiving his orders from Thiệu, he planned to go to the battlefield in his helicopter on February 23rd. Shortly after leaving the Bien Hoa airport, the plane suddenly lost power and crashed. The death of General Đỗ Cao Trí was an extremely severe blow to the ARVN, which already lacked experienced personnel.

The next target of the victorious NVA was the fire support base 31, which housed the 3rd Airborne Battalion and the headquarters of the 3rd Airborne Brigade. This base was practically the last obstacle that lay between the North Vietnamese and the column in the valley. After the camp was encircled and heavily bombed, Colonel Nguyen Van Tho, commander of the 3rd Brigade, sent the 6th Airborne Battalion to clear the encirclement. These soldiers were already Colonel Tho's last reserve. But the soldiers of the People's Army counted on this train. When the machines started to land to unload the men, the North Vietnamese opened fire with numerous guns at the same time. The helicopters were unable to maneuver so quickly and suffered catastrophic losses. Before even one man could go into battle, the battalion had more than 100 dead and wounded. The airborne division commander, Lieutenant General Dư Quốc Đống, was dissatisfied with his men having to occupy defensive positions. General Lam's plan limited their aggressiveness. Helicopter support to the base became impossible due to persistent anti-aircraft fire. To end the siege, General Đống requested tanks, but these never reached their destination.

Why could never be clarified. Probably conflicting orders and poor communication were the cause. After four days of continuous fire, the North Vietnamese, equipped with new rapid-fire rifles, finally launched a general attack. First advances could be repelled with the help of bombers and artillery. As a result of the heavy bombardment, however, FSB 31 was enveloped by a huge cloud of smoke and dust that blocked the view of what was happening. Just as the NVA was preparing for the next attack, an F-4 Phantom bomber was shot down nearby. The air traffic control officer, who coordinated all air strikes, then left his post to coordinate the search for the pilot. But this sealed the fate of the base. With the help of heavy T-54 tanks, the attackers managed to break through the defenses and capture the base within 40 minutes. Brigade commander Tho and his staff were trapped in a collapsed bunker. The North Vietnamese soldiers were already on the bunker and tried to break into it. The officers asked for artillery fire at their own position, and this came, but without any effect. During the battle for FSB 31, the NVA succeeded in killing 155 enemies and taking more than 100 prisoners, losing around 250 of their own men and 11 light tanks. The 3rd Paratrooper Brigade had lost almost the entire 3rd Airborne Battalion including the battalion commander Lieutenant Colonel Phat, its commander and officers' staff, and its battery of 105 mm guns. Only a few survivors managed to escape.

A few days earlier, the first tank battle of the Vietnam War occurred north of Straße 9. The tanks of the 17th Armored Battalion, together with units of the 8th Airborne Battalion, were able to hold their own against the North Vietnamese in a total of three battles. With the help of American air strikes, they managed to destroy 17 PT-76 and 6 T-54 tanks. The ARVN lost 25 troop transports and three of their five M41 tanks , as well as more than 200 soldiers. It is said that more than 1,100 North Vietnamese were killed, but recent findings show that this information was less likely to correspond to reality. In a battle that followed shortly afterwards, another 400 enemies are said to have been killed with the help of air strikes. Although the ARVN succeeded in temporarily stopping the advance of the North Vietnamese, it was unable to prevent the fall of the fire support bases. The 1st Armored Brigade had dug in north of the FSB A Loui and was the last obstacle that lay between the NVA and Road 9.

The occupation of Xépôn

After these dramatic events, there was no more serious fighting for the time being. Both sides prepared for their next steps. The NVA had meanwhile received support. General Văn Tiến Dũng had traveled to the front from Hanoi to oversee the progress of the battle. There were also changes on the South Vietnamese side. President Thiệu suggested to the General Staff that they should send the marines to the front instead of the paratroopers. General Lãm, however, recognized the difficulties and risks of deploying marines instead of paratroopers. So he flew to Saigon on February 28th to offer Thiệu an alternative. According to Lãm's plan, the units of the 1st Infantry Division would expand their bases towards Xépôn , while the Marines behind them would take control of the individual FSBs. Additional armored units would provide more firepower and fill up any losses. President Thiệu finally agreed. This plan kept the losses as small as possible, but the conquest of Xépôn was only delayed further.

Xépôn itself had long since been abandoned by this time. Heavy bombing had destroyed more than 6,500 houses, which was practically the entire city, and all residents had fled. The surrounding forests and hills housed large quantities of supplies and the NVA supply lines also ran outside the city. Xépôn itself therefore had no strategic or military value. The conquest of the city was of more political and psychological importance, because if Saigon's forces could at least manage to occupy the city, Thiệu would have an excuse to declare the operation a success. The journalist Henry Kamm once wrote: "Xépôn became to US troops and Saigon what Moby Dick became to Captain Ahab - the object of a deluded, destructive obsession."

Under these conditions, Thiệu and Lãm decided to attack Xépôn. Instead of the battered airborne troops, they sent the 1st Infantry Division to conquer the city. Two marine infantry brigades took over the fire bases Delta and Hotel, which replaced the units of the 1st Division. This, however, reduced the strength of the National Reserve to only one brigade of Marines. On March 3, the troops began to be deployed. During the transport by helicopter, another NVA trap snapped shut. When a battalion was brought into the FSB Lolo, eleven helicopters were lost to anti-aircraft fire, and 44 others were damaged. On March 6th, an armada consisting of 276 combat and transport helicopters soared into the sky and brought the entire 2nd and 3rd Battalion of the 3rd Regiment from Khe Sanh to Xépôn . Only one helicopter was lost to ground fire and the troops were dropped off at the Hope landing zone, 4 km northeast of the city. On March 8, the 2nd Battalion, under the command of Major Hue Ngoc Tran, entered the cremated site. Major Tran, called "Harry" by his American friends, was one of the best officers in the ARVN and was wounded four times during several skirmishes. During the occupation of Xépôn , he was appointed lieutenant colonel . His units searched the area and Xépôn himself for two days , but found disappointingly few enemy supplies. Only a single larger store of 122 mm rockets, as well as a few corpses and burned-out vehicles, were found. On March 9, the units began to march back to the FSB Sophia. Always on the lookout for ambushes, they had to switch to FSB Delta I after all. The North Vietnamese response to the occupation was increased shelling of the nearby bases.

retreat

Moon, Lolo, Sophia, Liz, Brown, Delta I

After the "conquest" of Xépôn , ARVN officers reported to reporters the alleged successes and further attacks on the enemy supply depot at Muong Phine. In fact, however, the defenses south of Road 9 began to increasingly crumble. As the ARVN troops had achieved their goals in Laos, Thiệu and General Lãm ordered their retreat, which began on March 9th. The retreating armed forces should destroy all storage areas and as much enemy supplies as possible. General Abrams suggested that Thiệu send the 2nd Infantry Division as reinforcements. She should stay in Laos and cut off the enemy supply routes until the start of the rainy season. If this had succeeded, major troop movements and a possible offensive would have had to wait several months later until the end of the rainy season. But Thiệu could not be convinced, the retreat continued as planned.

Meanwhile, the situation for the ARVN became more and more threatening. In order to meet the demands of such a large operation even halfway, the Americans pulled together helicopters from all over Vietnam, even from the Special Forces . But as the number of machines increased, the losses became more and more dramatic. By this time, hundreds of combat and transport helicopters had already been destroyed or damaged. Because despite the continuing heavy bombardment, the air defense systems of the NVA were hardly weakened. Additional anti-aircraft missiles were even positioned west of the Ban Raving Pass, which posed an additional threat to high-flying machines. The North Vietnamese became increasingly confident and attacked the enemy army aggressively and openly. In the past the NVA had to accept defeats several times, but this time they had more leverage. They had no problem with replenishing their troops and had greater reserves than their enemies. The armored forces, which were criminally underestimated before the battle, were very effective and well managed. One month after the operation began, the NVA was finally able to muster almost twice as many combat troops as their enemies. The morale of the soldiers was very high, because this time they too had tanks and artillery, and it was the ARVN that was on the defensive.

Starting with FSB Lolo, there was soon no stopping the NVA. The heaviest fighting so far during Operation Lam Son 719 would take place there. After March 8, supplying the FSB became increasingly difficult. On March 11th, the 1st and 2nd Regiments began to withdraw from the northwesternmost bases Sophia, Liz and Lolo. After the 2nd Regiment had left the FSB Sophia, American bombers had to destroy the eight 105 mm howitzers that had been left behind so that they would not fall into the hands of the NVA. At FSB Lolo, however, the situation became more and more hopeless. After all escape routes had been cut off, the soldiers had no choice but to attempt an escape. The 4th Battalion defended the flanks while the rest of the regiment withdrew. Most of them managed to escape, but the 4th Battalion was on the run for four more days from the approaching enemy. The North Vietnamese overtook the ARVN troops near the Sepon River . In a short battle, the unit was completely destroyed. The battalion commander and almost all officers were killed, a total of only 82 mostly wounded soldiers could be saved.

But things were going to get much worse for the ARVN. Delta Fire Support Base was held by the 147th Marine Brigade. The NVA was aware that it had the opportunity to wipe out one of the best units of the ARVN. Therefore, FSB Delta was completely surrounded by two elite regiments, the 29th and 803rd of the 324th Infantry Division. With the help of countless air strikes, the base could be held for a while. But then the ammunition supplies ran out. On March 22nd, with the help of ten flame throwing tanks, the NVA launched a major attack. Since the men were no longer able to stop the seemingly endless onslaught of the enemy, the brigade made a desperate attempt to break out. One survivor reported, “The last attack came at 8:00 pm. They first shot at us and then moved towards our position with tanks. The entire brigade ran down the hill like ants. We jumped over each other to get out of the base. No man had time to look after his officer. It just said quick, quick, quick, or we would die… When I was far from the hill there were about 20 Marines left, one lieutenant with us. We moved like ghosts, in constant fear of invasion by the North Vietnamese. Many times we stopped when we heard gunshots - and held our breath ... Our group came across a North Vietnamese unit and we ran like ants again. The lieutenant whispered, 'Spread out, don't stay together, or we'll all die.' After every firefight we became fewer and fewer. ”On the run, the battalions of the 147th Brigade NVA troops lay in wait, which completely dispersed their units. Most of the soldiers managed to flee, but the unit's losses were devastating. While the 258th Marine Brigade was able to leave relatively undisturbed, the 147th had more than 400 dead and missing as well as 650 wounded, which represented more than half of its crew strength. How many NVA soldiers were killed or injured is difficult to say. The Allies spoke of an allegedly 3,000 enemies killed, with an original crew of 4,200. These figures are, however, most likely greatly exaggerated.

Like the 147th Brigade, some other units fared. All the remaining FSBs became the scene of fierce and bloody battles. The worst hit was the elite battalion of war hero Lieutenant Colonel "Harry" Hue Ngoc Tran. The 2nd Infantry Battalion, called the "Black Wolves", was able to withdraw in an orderly manner at first. However, supplying the unit became impossible as it made its way through the dense rainforest. Again and again they came across North Vietnamese fighters who gradually decimated the battalion. After a while, they were forced to drink their own urine in order not to die of thirst. On March 21, the unit was ambushed by North Vietnamese and all but one man was wiped out. Lieutenant Colonel Tran was seriously injured and captured.

Fight on Street 9

In view of these dramatic events, concerns in the General Staff of the ARVN increased. General Phạm Văn Phú, commander of the 1st Infantry Division, recommended General Lãm to withdraw the troops from Laos as soon as possible. The other generals were amazed at Phú's nervousness, as they had never seen him in such a mood before. Not only the South Vietnamese, but also the American commanders in Saigon and Washington were very surprised by the course of the battle. They realized that a crushing defeat for the ARVN had to be prevented. Soldiers' morale continued to deteriorate, because when even men like Phạm Văn Phú were shaken and war heroes like Hue Ngoc Tran and Nguyen Van Tho were captured, normal soldiers had little reason to be optimistic.

After the defeats of the rangers, paratroopers and marines, the situation turned against the armored troops. The column around the 1st Armored Brigade had remained in Ban Dong for more than three weeks . Road 9 was in poor shape from the start, but the heavy bombing by the Americans only made the situation worse, as many vehicles got stuck in the myriad bomb craters caused by the US Air Force. Colonel Luat had meanwhile arrived in Ban Dong and had the place converted into a fortress. He had converted his tanks for static defense positions. On March 17th, the NVA began to encircle the troops, and enemy patrols were ambushed again and again. The ARVN was closely watched and on March 19 the brigade began preparations for a retreat. Therefore, the People's Army decided to attack. The 675B artillery regiment exposed the enemy with a two-hour artillery fire. A large concentration of firepower by North Vietnamese standards. Meanwhile, the 2nd Division was moving along Street 9 towards the ARVN's positions. Elements of the 308th and 324B Divisions approached from the north, and the tanks of the 202nd Armored Regiment supported numerous other units. After two days of bitter fighting, the NVA managed to break through the defenses of the South Vietnamese. In order to cover the withdrawal of the remaining armored troops, the airborne division had to make great sacrifices. More than 1000 paratroopers were killed and several hundred captured, the 1st Airborne Brigade ceased to exist as a functioning unit. Ban Dong itself was literally razed to the ground. With the help of American air strikes, the NVA was held up long enough to enable the 1st Armored Brigade to retreat. But then, at Ban Houei Sane, the force was again ambushed by North Vietnamese. Four M41 tanks and several vehicles were destroyed and almost 100 men were injured or killed.

By this time the force had already lost countless vehicles, the American pilot Lt. Col. Robert Darron reported: "Street 9 was littered with rubble, tanks and trucks and all sorts of things ... more than a mile long." They learned that even more from a prisoner Ambushes ahead were waiting for them. Colonel Luat decided to leave the road so as not to be completely destroyed. On March 21st, in the middle of the night, the column made its way through dense rainforest. On the afternoon of the 23rd, they crossed the Sepon River and returned to Vietnam. Colonel Nguyen Trong Luat still had 20 tanks and around 50 armored personnel carriers, but 71 tanks and more than 100 other vehicles were left in Laos. Many ran out of fuel and were destroyed by US bombers.

Meanwhile, Khe Sanh and the other bases behind the Vietnamese border came under artillery fire. Units of the 19th, 25th, 31st and 33rd Storm Pioneer Battalions, as well as the 15th Engineer Regiment of the People's Army launched several successful attacks on FSB Vandegrift and the Khe Sanh Combat Base. Between March 8 and 23, a total of six helicopters, three main ammunition dumps and numerous bunkers and fuel depots were blown up. In Vandegrift alone, 36,000 gallons (approx. 136,000 liters) of fuel and 8,600 rounds of 20 mm ammunition were destroyed. In Khe Sanh, the storm pioneers killed three Americans and wounded fourteen, while they themselves lost only fifteen men.

The last units of the ARVN left Laos on March 24th. Weeks ahead of the schedule that was supposed to be a longer stay in the country. Khe Sanh was also to be held until May, but pressure from enemy troops also accelerated the withdrawal of US troops. On April 6, the Khe Sanh Combat Base was blown up for the second time (after 1968) by the Americans. Units of the 4th ARVN armored cavalry led the march back. It was almost indicative of the whole mission that this large convoy did not move for more than two hours due to only one broken down truck.

Losses and consequences

Army of the Republic of Vietnam

On March 24, after the last ARVN troops fled Laos, President Nixon interviewed ABC's Howard K. Smith . This was to avoid the impression that the invasion of Laos was a failure. During the interview, he presented numbers and statistics on alleged enemy losses, captured supplies, the performance of the ARVN and so on. But most of these statistics were unfounded. For example, it was claimed that of a total of 22 ARVN battalions, only four fought less well, while all the others had proven their worth. In fact, however, these four battalions were not judged effective because they were almost completely wiped out, not because they fought poorly. The 1st Armored Brigade, in turn, was rated effective even though it had lost 50 percent of its men and far more than half of its vehicles. At least six other battalions had to be completely rebuilt after the end of the operation. The marines, paratroopers and the 1st Division had lost about a third of their manpower in Laos, the three ranger battalions and the 1st armored brigade more than half. These were certainly not the numbers of a victorious army.

According to President Nixon, the NVA lost 3,754 small arms, 1,123 machine guns, anti-aircraft and artillery pieces, 110 tanks and 13,630 tons of ammunition, the figures presented by the ARVN were much higher. However, these details were all highly imprecise, and some were deliberately exaggerated in retrospect. So is z. For example, there was always talk of 110 enemy tanks destroyed, even though the Americans could only count 88 in reality. There was particularly great controversy over the information provided by the NVA soldiers killed. After the end of the operation, the ARVN spoke of 13,345 dead and the XXIV. Corps of more than 14,000, and later even of 19,000 dead. However, new research showed that the actual numbers were much lower. In reality, the NVA had 2,163 dead and 6,176 wounded.

However, the ARVN's losses are still not exactly known. First there was talk of 1,147 dead, 246 missing and 4,237 injured, later a general reported 1,529 dead and 5,483 injured. But even then these reports were questioned. However, it is known that the ARVN lost a total of 2500 small arms, 96 artillery pieces, about 400 machine guns , 71 tanks, well over 100 vehicles and 1517 radios. Hanoi, in turn, spoke of 16,400 wounded, fallen and captured ARVN soldiers and 200 dead Americans. Often they too had published figures that did not correspond to reality. This time, however, it is very difficult to refute them. Thiệu had done everything possible to prevent a realistic estimate of the losses. The American newspapers Time and Newsweek, as well as other newspapers whose reports did not correspond to Thiệu's version of the matter, were banned. The severely ailing marine and airborne troops of the ARVN stayed in the north of the country instead of returning to their bases near Saigon. This was to prevent their bloodcurdling reports from reaching the public. In fact, the North Vietnamese reports of around 5,500 dead, 10,000 wounded and almost 1,000 prisoners are quite realistic and irrefutable figures.

The loss of some experienced officers was also of great significance. The ARVN was an army in the early 1970s that increasingly lacked professional leaders. In 1970, for example, 60% of all battalions were commanded by captains who were actually only allowed to command companies of a maximum of 150 men. It didn't look much better at the higher ranks either. In addition to the war heroes Lieutenant Colonel Hue Ngoc Tran, Colonel Nguyen Van Tho and General Đỗ Cao Trí, several other battle-hardened officers were killed or captured, while General Lãm retained his post even after this defeat. The ARVN could not make up for the loss of these men; it would prove to be a great disadvantage in future battles.

The American

Even if you would think that the American numbers should be fairly accurate, this is not the whole truth either. The number of dead and wounded is known, the Americans had to mourn 253 dead and missing and 1,149 wounded. But the official number of lost helicopters was glossed over afterwards.

The Americans encountered anti-aircraft defenses in Laos that they had never seen before. The nature of warfare had changed completely, a helicopter pilot reported: "We are fighting a conventional war out there, helicopters ... are not built to counter such defenses." The NVA had a wide range of anti-aircraft guns in Laos, 12 were observed , 7mm, 23mm, 37mm and 57mm guns and even surface-to-air missiles (SAM). However, the 12.7 mm machine gun turned out to be the most effective. Machine-gun positions with an overlapping field of fire were always no more than a kilometer from any potential landing zone. Helicopter pilot Major Burt reported: “I've been flying for 6 months, got my first hit yesterday and since then I've got 13. We had a 100 percent hit rate, 7 out of 7 helicopters were hit. ”In Vietnam, the liberation fighters mostly let enemy machines fly by so as not to reveal their position. In Laos, however, they shot practically every target. The bad weather also increasingly restricted the maneuverability of the helicopters. In addition to machine-gun fire, mortar fire during landing was also a constant problem, which many machines fell victim to.

The large number of helicopter losses shocked many Americans and led to the fundamental doctrine of air support being challenged . According to the XXIV Corps, 108 helicopters were destroyed and 618 damaged. However, these figures are rather misleading. Helicopters were not considered destroyed if they could be recovered and machines were considered damaged, only a small part of which could be recovered. An American reconnaissance colonel once said: "If you could get the tail number out of the wreck and stick it on a new helicopter, you would never admit that the machine was lost." Therefore the official figures are still an understatement, the proportion of " damaged “helicopters that were actually destroyed was much higher than stated.

Road 9 South Laos Victory

For the North Vietnamese side, the “Road 9 South Laos Victory” was a resounding success. They had managed to decimate some of the best units the enemy could muster and to throw them out of Laos. The People's Army has certainly suffered some heavy losses. But these were nowhere near as heavy as those of the ARVN. This could not achieve any of its goals, the invasion had not brought lasting success. Traffic on the Ho Chi Minh Trail was briefly interrupted, but reconnaissance photos only a week later showed a large increase in transports along the trail. The offensive power of the NVA was only marginally reduced, but in return the defense capabilities of the ARVN were severely affected. The air defense was massively reinforced following the operation, from 600 to 700 guns to over 1500 a few months later. The effect sought by Operation Lam Son 719 did the opposite. After the ARVN withdrew and the bombing ceased, the door and gate to North Vietnamese agitation were open.

literature

- Marc Frey : History of the Vietnam War. The tragedy in Asia and the end of the American dream . Beck-Verlag, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-45978-1 .

- John Prados: The Blood Road: The Ho Chi Minh Trail and the Vietnam War . John Wiley & Sons, New York 1998, ISBN 0-471-25465-7 .

- David Fulghum, Terrence Maitland: South Vietnam On Trial: Mid-1970 to 1972 . Boston Publishing Company, Boston 1984, ISBN 0-939526-10-7 .

- Bernd Greiner: War without fronts - The USA in Vietnam . 1st edition. Verlag Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-86854-207-3 .

- Keith William Nolan: Into Laos: The story of Dewey Canyon II / Lam Son 719, Vietnam 1971 . Presidio Press, Novato, California 1986, ISBN 0-89141-247-6 .

Web link

- Propaganda film: Rebuilding a destroyed village (US Department of Defense, 1967)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Fulghum: South Vietnam on Trial . 1984, p. 76 .

- ^ A b c Fulghum: South Vietnam on Trial . 1984, p. 70-71 .

- ↑ Nolan: Into Cambodia . 1986, p. 358 .

- ↑ a b c d Fulghum: South Vietnam on Trial . 1984, p. 90 .

- ↑ Frey: History of the Vietnam War . 2004, p. 201 .

- ^ Greiner: War without fronts . 2009, p. 167 .

- ^ Fulghum: South Vietnam on Trial . 1984, p. 65 .

- ↑ Prados: The Blood Road . 1998, p. 317 .

- ^ Fulghum: South Vietnam on Trial . 1984, p. 66 .

- ^ Fulghum: South Vietnam on Trial . 1984, p. 9 .

- ^ Fulghum: South Vietnam on Trial . 1984, p. 72 .

- ^ A b Prados: The Blood Road . 1998, p. 330 .

- ^ A b Prados: The Blood Road . 1998, p. 336 .

- ↑ Prados: The Blood Road . 1998, p. 335 .

- ↑ Prados: The Blood Road . 1998, p. 333 .

- ^ Fulghum: South Vietnam on Trial . 1984, p. 78-79 .

- ^ A b Prados: The Blood Road . 1998, p. 341 .

- ↑ Prados: The Blood Road . 1998, p. 311 .

- ^ Fulghum: South Vietnam on Trial . 1984, p. 85 .

- ^ A b Fulghum: South Vietnam on Trial . 1984, p. 86-87 .

- ↑ Prados: The Blood Road . 1998, p. 344 .

- ^ A b c Fulghum: South Vietnam on Trial . 1984, p. 88-89 .

- ^ A b Prados: The Blood Road . 1998, p. 352-353 .

- ^ A b Prados: The Blood Road . 1998, p. 353-354 .

- ^ A b Prados: The Blood Road . 1998, p. 355 .

- ↑ Prados: The Blood Road . 1998, p. 358 .

- ^ Fulghum: South Vietnam on Trial . 1984, p. 96 .

- ↑ Prados: The Blood Road . 1998, p. 360 .

- ^ Fulghum: South Vietnam on Trial . 1984, p. 91 .

- ↑ Indochina: The Invasion Ends. In: Time.com. Time Magazine, April 5, 1971, accessed February 23, 2011 .

- ↑ Lam Son 719 Operation. In: Vnaf Mamn, Untold Stories. Retrieved February 23, 2011 .

- ^ Fulghum: South Vietnam on Trial . 1984, p. 57 .

- ↑ Prados: The Blood Road . 1998, p. 368-369 .