Battle for Khe Sanh

| date | Jan 21 to Apr 8, 1968 (American interpretation) Jan 21 to Jul 9, 1968 (according to North Vietnamese interpretation) |

|---|---|

| place | Khe Sanh, Vietnam |

| output | Both sides claim victory.

|

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 6,000 Marines, U.S. 26th Marine Regiment, 1st Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment, 1st Battalion, U.S. Marine Artillery, 37th ARVN Ranger Battalion, U.S. Special Forces , Air Force, Navy and Marines air support |

20,000 soldiers, 66th regiment of the 304th "Delta" Division, 2nd regiment of the 325C. Gold Star Division, 324B Division, 68th Artillery Regiment , 16th Artillery Regiment, several anti-aircraft companies |

| losses | |

|

A total of 242 dead and 1,014 wounded and two missing United States

199 dead, 830 wounded, South Vietnam

43 dead, 184 wounded

|

A total of between 1,500 and 10,000 dead; According to Vietnamese data, 2,469 dead (from January 20 to July 20, 1968) |

Vietnam War

Battle of Tua Hai (1960) - Battle of Ap Bac (1963) - Battle of Nam Dong (1964) - Tonkin Incident (1964) - Operation Flaming Dart (1965) - Operation Rolling Thunder (1965-68) - Battle of Dong Xoai (1965) - Battle of the Ia Drang Valley (1965) - Operation Crimp (1966) - Operation Hastings (1966) - Battle of Long Tan (1966) - Operation Attleboro (1966) - Operation Cedar Falls (1967) - Battle around Hill 881 (1967) - Battle of Dak To (1967) - Battle of Khe Sanh (1968) - Tet Offensive (1968) - Battle of Huế (1968) - Operation Speedy Express (1968/69) - Operation Dewey Canyon ( 1969) - Battle of Hamburger Hill (1969) - Operation MENU (1969/70) - Operation Lam Son 719 (1971) - Battle of FSB Mary Ann (1971) - Battle of Quảng Trị (1972) - Operation Linebacker (1972) - Operation Linebacker II (1972) - Battle of Xuan Loc (1975) - Operation Frequent Wind (1975)

The Battle of Khe Sanh , also Siege of Khe Sanh , took place between parts of the 26th and 9th Regiments of the United States Marine Corps and the 304th and 325C Divisions during the Vietnam War from January 21 to July 9, 1968 of the Vietnamese People's Army in Khe Sanh, Vietnam . Khe Sanh (official name: Khe Sanh Combat Base ) was a base of the Marines in South Vietnam , not far from the Laotian border in the province of Quảng Trị , south of the demilitarized zone to North Vietnam . In addition to the Tet Offensive and the Battle of Huế , the siege of Khe Sanh is considered to be one of the most important military operations during the Vietnam War. The siege ended without the North Vietnamese taking over the base. Since they also suffered the greater losses, the battle was proclaimed a victory by the USA. However, the military camp was abandoned and dismantled by the Americans after the battle; the US strategic goal of sealing off the border between North and South Vietnam with a series of heavily fortified positions had proven impracticable. In this respect, Khe Sanh was a tactical US victory - but a strategic defeat.

prehistory

Origin of the base

The first troops of the US Special Forces set up their camp in July 1962 not far from the town of Khe Sanh near an abandoned French fort. It was intended and planned as a training facility for CIDG troops. The troops stationed there were reinforced in the course of the year. In September 1962, pioneers in the South Vietnamese army built the base's first almost 400 m long runway . In the period that followed, the base was massively expanded and strengthened. It served as a starting point for explorations against the Ho Chi Minh Trail in the region and beyond the Laotian border. In addition, the base controlled one of the great valleys that lead from the demilitarized zone and from Laos to the southeast into the plains around Quảng Trị and Đà Nẵng .

In March 1964, an O-1 Birddog was shot down on a reconnaissance flight in the Khe Sanh area. The pilot, Captain Richard Whitesides, was killed and the observer, Captain Floyd Thompson, captured. Thompson was one of the first and longest remaining US soldiers in Vietnamese captivity.

In April 1964, the first units of the American Marine Corps arrived in Khe Sanh. During reconnaissance missions around the camp, including across the Laotian border, contact with the enemy was established several times, thus providing evidence that the north was sending troops to South Vietnam.

In the following two years the warehouse was expanded further. The Special Forces moved to nearby Camp Lang Vei in September 1966 and handed control of the Khe Sanh Combat Base to the Marines. These expanded the camp (with the help of the SeaBees ) in the course of 1967, including the extension of the runway from 500 to 1200 meters. However, since the runway was directly on the laterite floor , it became unusable during heavy rainfall, especially in spring. Therefore, the SeaBees removed the runway, built a new substructure made of rock and asphalt and laid new aluminum plates. This runway was then able to carry heavy aircraft like the C-130 Hercules even in bad weather .

At the end of April 1967, Marines patrols in the surrounding hills encountered strong North Vietnamese forces. Heavy fighting broke out by May 11 , during which the Marines succeeded in defeating the Vietnamese and occupying several key hill positions. The Vietnamese lost about 950 men. 155 Marines were killed in the fighting in the hills.

Khe Sanh Combat Base

The Combat Base itself stretched about 1.8 km along the Rao Quan River on a laterite plateau. The central element was a 1200 m long runway, which was fixed with aluminum grid plates and allowed aircraft up to the size of the C-130 Hercules to take off and land. The runway did not have a taxiway, so the aircraft had to turn around on the main runway in order to get to the taxiway and thus to the unloading zone. South of the runway were the accommodations and command posts of the 26th Marines, the ARVN rangers, as well as the command posts of the field artillery and the runway's flight control center. Next to the eastern end of the runway, the base's ammunition was stored in Ammo Dump 1. Another, but much smaller, ammunition store was located south of the runway in the center of the base.

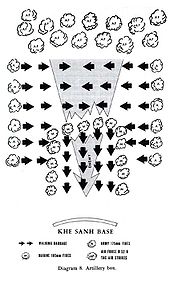

The defenders had 18 105 mm M101 howitzers with a range of 12 km, six 155 mm M114 howitzers with a range of 14.6 km and six 107 mm M30 mortars with a range of 4,020 m. Then there were the long-range 175 mm M107 cannons , which were stationed east of Khe Sanh on the Rockpile and in Camp Carrol and could fire the access routes to the base. For direct base defense, six M48 main battle tanks , ten M50 Ontos , four M42 Duster and several Guntrucks with 12.7 mm quadruple MG Browning M2 were distributed around the base in firing positions and partially buried.

The Marines also occupied Hill 881 South and Hill 861 north of the base , which overlooked the base's plateau, and Hill 558, which blocked off the valley of the Rao Quan River. A radio relay station was located on hill 950 east of the river (see map 3). During the siege, other nearby hills, such as hill 64 in the plateau, were occupied by marines and some of them were converted into fire bases for artillery support.

Preparations for the Siege

As patrols around the base during Operation Scotland and as part of the electronic reconnaissance during Operation Niagara I at the end of 1967 showed, massive units of the North Vietnamese Army under the command of the 304th Division, which had already fought against the French at Điện Biên Phủ , through the demilitarized zone south to the region around Khe Sanh.

General Westmoreland reinforced the troops in Khe Sanh to be able to withstand a possible attack. Similar to the French at Điện Biên Phủ, the American high command was looking for a decision in the conflict with North Vietnam. The Vietnamese were also happy to get involved in this battle. A victory at Khe Sanh would have cleared the way into the flat coastal country, and additionally made it almost impossible for the Americans to control the Ho Chi Minh Trail running through the mountainous region. As a result, the North Vietnamese could have brought their supplies to the south almost undisturbed.

In the following months there were repeated attacks on positions of the Marines around Khe Sanh. However, they did not remain inactive and undertook several attacks on positions of the Vietnamese, who had set up their artillery positions in the hills northwest of the base. The most successful was an attack by a platoon of the 26th Marines on January 20, 1968, the day before the siege began, when the enemy was almost able to displace the enemy from Hill 881 North. However, since a Vietnamese officer defected to the Americans that day and informed them of the imminent attack, the troops were withdrawn and the defenders of the base were put on high alert.

The siege

Beginning of the siege

Shortly after midnight, on the early morning of January 21, 1968, hill 861 was shelled by North Vietnamese mortars . Shortly afterwards, sappers tried to blow up the barbed wire barriers that were built around the positions on the summit, thus creating a way for the infantry into the positions of the marines. The attackers were repulsed, among other things, because they ignored Hill 881 South and were therefore under fire from the higher positions of the Marines the entire time during the attack. At around 5:30 am, the artillery and mortar fire from the surrounding mountains began to hit the base itself. One of the first shells hit the main ammunition depot, which contained over 1,500 tons of ammunition, more than 90% of the base's inventory. In the massive explosions that followed, which lasted over 48 hours, 18 US soldiers died and 43 were injured, some seriously. At the same time, NVA troops attacked the village of Khe Sanh, which was held by Marines and South Vietnamese rangers. The first attack broke through the defense, but was successfully repulsed. After a second attack on the same day, the defenders withdrew to the Khe Sanh Combat Base and left the village to the North Vietnamese without a fight. In the course of the following days there were repeated armed reconnaissance of the Vietnamese against the defense lines of the Marines, but the expected major attack did not materialize. Instead, the gunners of the North Vietnamese artillery shot themselves at the base, which fell on average around 300 shells per day.

Khe Sanh under constant fire

Continuous fire from North Vietnamese guns became a daily practice for the marines at the beleaguered base for the next two and a half months. The Marines countered the danger posed by the falling artillery and mortar shells by expanding and strengthening the accommodations and bunkers so that they could withstand at least mortar shells and light artillery hits, and by building a network of barrel and fragmentation trenches within the base.

The air supply to the base turned out to be very difficult in parts in the following two and a half months. On some days the soldiers' food rations had to be restricted. Despite the fortifications, there were repeated wounds and deaths from artillery hits. In addition, there was a plague of rats in the bunkers and accommodations, as, due to the rainy weather in spring, these were the only reasonably dry places within the base. Otherwise, the laterite soil quickly turned into a mud landscape.

In addition to these external circumstances, there was the psychological pressure that weighed on the besieged, because in the mountains around the base a three-fold superior force of the North Vietnamese army was waiting to attack them. There were repeated long fire duels between the artillery of the base and the guns of the North Vietnamese in the hills.

The psychological pressure reached up to the White House , where President Johnson was informed daily about the current situation using a model of the Khe Sanh Combat Base. At the beginning of the siege, Johnson had obtained assurance from his chief of staff that the base was to be held. The White House crisis center was also manned around the clock for the first time during the Vietnam War.

Battle for Lang Vei

Camp Lang Vei was created when the Special Forces withdrew from Khe Sanh in 1966. The camp was about 9 kilometers from the USMC base, on Highway 9 to Laos . In the two years up to 1968 a small but well-developed and fortified camp was built. It consisted of a central area in which the command center was located in a heavy concrete bunker, as well as 4 x-shaped defensive positions, which secured the base in all directions. The base was surrounded by a chain link fence, in front of which Claymore mines lay 50 m apart . The defensive positions were constructed from thick wooden beams and sandbags and had a very good fire field. Mutual fire protection was also possible.

The camp was defended by around 200 Green Berets and Mike Force soldiers, who had two 106 mm recoilless and four 57 mm guns, two M2 machine guns and, as of January 24, about 100 LAW anti-tank weapons . These had been brought to the camp after both aerial reconnaissance and reports from Laotian volunteers whose camp had recently been overrun, reported tank movements. In addition, there were around 290 CIDG irregulars who were stationed in the old Camp Lang Vei, a few hundred meters from the SF camp.

The Vietnamese attack on the camp began on February 6 at 12:42 am, supported by eleven PT-76 tanks made by the Soviet Union. Under cover of the tanks, enemy engineers advanced to cut holes in the wire fence around the camp. When the first flares rose from the "flare traps", the defenders became aware of the situation and opened fire on the attackers. Two tanks were destroyed by the 106 mm guns, another received a direct hit with a bazooka and remained lying. However, many of the LAWs failed when fired or did not detonate on impact on the target.

Accordingly, the attackers still had tanks available; these maneuvered around the wreckage and broke through the outer defenses of the camp. The PT-76 now took the positions of the Green Berets with their main guns under fire. Within a short time, the defenders were encircled in a few pockets of resistance from which they fiercely defended themselves and hoped for relief from Khe Sanh and Da Nang. Since the Vietnamese had meanwhile occupied all night landing zones around and in the base, reinforcement by troops flown in with helicopters was impossible. The "Highway 9" could not be used as an access route for reinforcements, as the village of Khe Sanh, which is controlled by the North Vietnamese, would have had to be crossed. The defenders received support from the air alone, a forward air controller of the Air Force, who circled over Lang Vei with his observation aircraft, directed several light bombers and fighter-bombers , which could take out two more tanks with bombs and missiles. Since the enemy was now between the American defenders, the use of napalm or cluster bombs was out of the question.

From the old Lang Vei camp a few hundred meters away, SFC Eugene Ashley organized a counterattack with the Lao and local troops, but got stuck in enemy fire and was fatally wounded when attempting to reach the camp later. The surviving US soldiers holed up in the command bunker and continued to defend themselves until late afternoon, when they managed to escape under the protection of massive air raids. Of the 24 Special Forces soldiers, four were killed, nine captured, and the rest escaped. Of the other defense lawyers (CIDG, Mike Force, LLDB), the Irregulars suffered the highest losses with 165 men. The defenders lost a total of 217 men. According to estimates by the Americans, the attackers lost around 250 to 500 men.

With the conquest of Lang Vei, the North Vietnamese now had the opportunity to obtain material for the besiegers along Highway 9 undisturbed by the Americans. In addition, the threat to the attackers' southwest flank was averted. Historians also see this as the reason why General Giap used tanks during the conquest. On the other hand, most of the tanks used were destroyed in the attack on Lang Vei (seven confirmed, two others not certain), so that a massive tank attack on Khe Sanh himself, which would also have caused some problems for the defenders of the base, was no longer to be feared .

Supply from the air

Since the base was now completely enclosed by the enemy, but around 120 tons of material were required daily for the supply of around 6,000 soldiers stationed there and the defense of the camp, the supply had to be entirely from the air. This was not without risk, as the North Vietnamese had set up several air defense positions with machine guns and light anti-aircraft guns in the hills around Khe Sanh and from there they took the slowly approaching supply aircraft under fire. In addition, there was mortar and artillery fire that started immediately when the aircraft touched down and taxied to the unloading point.

To supply the base were C-130 Hercules with 20 tons of cargo capacity, C-123 provider with 7 tons capacity and C-7 Caribou with 3 tons of capacity.

At the beginning of the siege, the planes landed, albeit at high risk, and unloaded their cargo on the tarmac. On February 11, however, a KC-130 of the Marine Corps, loaded with 10 tons of fuel for helicopters, was hit by a mortar shell after landing and burned out. Six crew members and passengers were killed. In response to the incident, the airfield was closed and the Americans were feverishly looking for a new way to supply the trapped troops. A few days later, air traffic was reopened for smaller machines such as the Provider and the Caribou, as they did not have to use the entire runway. Since these machines had too little cargo capacity to handle the supply alone, other, less dangerous ways had to be found for the Hercules to get their cargo to the Marines.

One of these possibilities was the so-called Low Altitude Parachute Extraction System , in which the aircraft flew at a height of about one to two meters over the runway and the cargo stowed on pallets was pulled out of the aircraft's rear hatch on a parachute (see picture). The pallets then slid a few meters further and then stayed where they were. However, there were several spectacular incidents in Khe Sanh when the pallets shot over the end of the runway and crashed into the bunkers at the east end of the runway.

In another procedure, also carried out at low altitude, a rope was stretched across the runway and the pallets were pulled out of the loading bay on a hook (similar to landing on an aircraft carrier ).

Most supplies were dropped by parachute. The base's drop zone was just outside the eastern boundary of the base and was approximately 300 meters long and 100 meters wide. This required the most precise timing; a delay of one second would have meant that the entire load would have missed the drop zone. The exact coordination was carried out with the help of the radar of the base and precise planning and timing by the navigator of the aircraft being dropped.

In the 77 days, over 8,000 tons of supplies were dropped by parachute in over 600 missions, and a further 4,000 tons were unloaded on the ground in a total of 460 approaches. Three C-123s were lost to enemy fire during the missions.

The battle for the hill outposts

The positions of the Marines on the hills surrounding the base were essential for the defense - a loss of one or more positions would have meant the quick end of the siege. For these reasons, up to 20% of the troops (about 1200 men) were posted on the hills.

The Marines turned the hill positions into firebases in order to fight the North Vietnamese, who, as with Hill 881, had partially fortified their positions only a few meters away in the months before the siege began. In direct firefights with machine guns and in repeated advances and explorations, both sides suffered high losses, the failure rate of the Americans was sometimes 50%. In addition to the risk of a direct attack, there was also the constant threat of artillery and snipers, which the Americans countered with the massive use of fighter-bombers and artillery.

Each hill post had its own Forward Air Controller (Air Force forward observer) who instructed the fighter-bombers on their attack missions. For this purpose, white smoke was used to mark the target during the day and flares at night, which were fired by mortars in the positions. The corrections and deviations were then transmitted by radio to the pilots, some of whom dropped their weapons loads less than 200 meters away from the American positions. "We could feel the heat of the burning napalm on our faces" (We felt the heat of the burning napalm on our faces) wrote a marine in his memories. The fight was carried out around the clock, at night the marines used the lighter-burning Russian gunpowder to locate enemy positions and to fight them with artillery or recoilless guns.

The supply of these outposts was only possible via helicopter - every shot of ammunition, every ration, fuel, soldiers, everything had to be flown in. This turned out to be more and more difficult over time, as the North Vietnamese took the helicopters under fire on the approach routes. As soon as these arrived in the landing zones, they came under mortar and rocket fire. This led to high losses and the supply situation for the troops on the hills deteriorated.

"Supergaggle"

Since the supply of individually approaching helicopters required too high losses and the location of the outposts quickly became critical, the Marine Corps developed an elaborate but effective tactic to supply the hills.

From now on, the helicopters no longer flew individually, but in groups of up to 16 machines and under the cover of combat helicopters and aircraft. Since this was an enormous time and logistical challenge, an Airborne Command and Control Aircraft, a flying command post, was available for every attempt.

At the beginning of the operation, four A-4 Skyhawks bombed well-known anti -aircraft, missile and mortar positions of the North Vietnamese with bombs and napalm . Two more Skyhawks first laid a tear gas curtain and then a smoke curtain along the approach corridor to block the view of the North Vietnamese shooters. Thirty seconds later, the CH-46 SeaKnights flew under cover from UH-1 Gunships , while four more Skyhawks flew close-range support. Some of the transport helicopters flew at just 10 seconds apart and dropped their loads (mostly loop loads) without stopping. If new reinforcements were flown in or the wounded were flown out, the helicopters only touched down for as long as was absolutely necessary. "We were literally thrown out of that chopper" writes Dave Powell in his memoirs. The closely approaching helicopters looked like a flock of geese, according to the marines, which is why the whole process quickly got its nickname “Supergaggle”. The whole operation lasted a maximum of five minutes and ensured supplies to the outposts. In the period that followed, only two helicopters were shot down while supplying the hill outposts, which is why the effort for this type of supply was worthwhile.

Defense from the air

Since a long-term defense of a base completely enclosed by the enemy had already proven impossible at the battle of Điện Biên Phủ, the Americans did everything in their power to avoid a similar fall. General Westmoreland therefore started Operation Niagara, a joint operation of the Air Force and the Navy . The name was chosen by Westmoreland himself, "because I Visualized your bombs falling like water over the famous case there in northern New York state" (I saw that your bombs fell down on them like water on that famous waterfall in upstate New York ).

Operation Niagara I

In the months before the start of the siege, when the large movements of the North Vietnamese troops were discovered, plans began for a large-scale reconnaissance operation in the region around the Khe Sanh Combat Base.

Patrols of the Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol , a special unit of the 101st Airborne Division , reconnaissance aircraft and, for the first time, electronic sensors were used for this purpose. These were dropped from airplanes and helicopters onto the suspected and known approach routes and operational areas and reported enemy movements to a situation control center, from where the information was passed on to the attacking units of the air force and navy during the subsequent attack operations. The information gathered enabled the air forces to react specifically to the movements of the North Vietnamese and to attack troop concentrations.

Operation Niagara II

The air strikes on the targets won by the reconnaissance during Niagara I were then carried out jointly by the Air Force and the Navy. The navy mainly provided carrier-supported fighter - bombers , which attacked enemy positions in close support missions. If the weather was and no fog or clouds made an approach impossible were the Marines around the clock fighter-bomber and ground attack aircraft available that enemy positions to a previously determined schedule or after instruction by the forward air control attacked in the base. In some cases several dozen operations per day, around 50,000 tons of bombs and 10,000 tons of napalm were dropped on the region around the base during the 77-day siege.

The sheer mass of bombs was dropped by B-52 Stratofortresses during ongoing Operation Arc Light , which were incorporated into the Niagara II attacks. The bombers approaching from Guam or Thailand dropped 23 tons of high-explosive bombs every 90 minutes around the clock in groups of three on the enemy positions around the Marines camp. Until February 18, they kept a distance of at least three kilometers from the base so as not to endanger their own soldiers. However, as the Vietnamese drove their tunnel and trench system closer and closer to the lines of the Marines, attempts were made to bring the bombers closer to the base and to drop the bombs about a kilometer away under the guidance of the base's ground penetrating radar. When the success of this attempt became apparent, the security zone around the base was reduced to one kilometer and the outlying "enemy territory" was almost "plowed up" during the weeks that followed. In total, the B-52 dropped around 60,000 tons of bombs on the region around the Khe Sanh Combat Base during 2548 missions. On some days this was three times more than what was used on an average day in World War II .

The end of the battle

Direct attack

The attacks on the base itself, throughout the duration of the siege, had mostly been limited to minor, violent explorations, mostly aimed at finding weaknesses in the defense. On February 29, however, the North Vietnamese Army's 66th Battalion attacked the base's western line of defense, which was occupied by units from the South Vietnamese 37th ARVN Ranger Battalion. Now the base's own defense plan came into effect. The artillery pieces stationed in the base cut off the attacking Vietnamese and covered them with a roller of fire that wandered up and down the section. At the same time, the Vietnamese flanks were taken under fire by the heavy American support artillery on the Rockpile and in Camp Carrol, while the Vietnamese units remaining behind were almost completely destroyed by massive air strikes. The surviving attackers were then wiped out in the direct fire of the defenders, the attack came to a standstill.

The attack subsides

After the North Vietnamese guns had almost become a habit for the Marines, the electronic sensors registered an increased increase in movements around the base in the penultimate week of March, which was accompanied by an increase in artillery fire. On March 23, over a hundred shells per hour fell on the base, a total of over 1,000 on that day. The defenders expected a massive enemy attack after this massive artillery preparation, but exactly the opposite happened: the enemy withdrew the majority of their troops from the region, only about 5000 North Vietnamese remained.

After moving little more than a few hundred meters from the base in the months to avoid the attacks of the B-52 bombers, the Marines undertook even small but aggressive attacks in the surrounding hills and captured some Positions that had previously been in North Vietnamese hands.

Relief by the 1st Cavalry Division

On March 31, the 2nd Battalion of the 1st Cavalry Division, along with units from the 1st and 26th Marine Regiments and the South Vietnamese 3rd Airborne Task Force, began a relief attack along Highway 9 to the west. The starting point for the attack called Operation Pegasus was the Stud landing zone, which had been expanded into a fire support base.

The US Marines and the South Vietnamese advanced along the road, while the 1st Cavalry Division secured the flanks in several airborne operations in landing zones north and south of the highway and drove the Vietnamese from positions in the hills. In the early afternoon of April 6, the first units reached the enclosed Khe Sanh Combat Base, which was reinforced at the same time with other units of the ARVN rangers. Two days later the road to the base was clear and drivable again after pioneers had restored Highway 9, which had been partially destroyed. The 1st Cavalry Division replaced the marines in the base, thus ending the 77-day siege of Khe Sanh. The operation Pegasus was officially completed on 14 April after units of the South Vietnamese Army and the 1st Cavalry Division further parts of the plateau had brought back under US control, while partly the impact of the bombings during Operation Niagara discovered - hundreds killed North Vietnamese, sometimes only sparsely buried, for the most part still where they fell.

Demolition of the military camp

The 26th Marines, who had been under fire most of the time in Khe Sanh, were dispatched to Dong Ha and Camp Carrol on April 18. On May 23, they received the Presidential Unit Citation from President Johnson in honor of their successful service in Khe Sanh.

In the following years, the Khe Sanh Combat Base was dismantled and largely abandoned, only a few artillery positions remained for a while to support further operations in the western Quảng Tr Provinz province. When it finally became apparent that President Johnson would not allow the conflict to spread to neighboring Laos due to the changed political situation in America, the base was finally evacuated on June 23 and the last units relocated eastwards. Mobile, rapidly moving units were now available in Ca Lu and LZ Stud for operations in the border area. The camp was no longer needed as a starting point for attacks on the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Result and analysis

Military

Although the battle ended successfully for the Americans, they could not gain any advantage from this situation because the political situation prevented it from expanding and thus preventing possible success. Nevertheless, it was made clear that a base completely enclosed by the enemy could be defended and supplied from the air.

In contrast, the US Department of Defense's plan to seal off the border between North and South Vietnam with a series of heavily fortified positions proved impracticable because, despite the massive deployment of troops and materials, supplies from the north could not be cut off.

For the North Vietnamese, however, the siege, like the Tet Offensive , was a heavy defeat. The goal of creating a free route to the south of Vietnam was not achieved; on the contrary, large parts of the troops deployed were killed or injured. The number of North Vietnamese killed varies, depending on the source, between 1800 (official North Vietnamese data) and 14,000 (highest American estimate). There are no exact numbers of the dead, the situation is also difficult because the massive bombing during Operation Niagara II “plowed up” the entire region and many corpses could no longer be found.

However, with the attack on Khe Sanh, the North Vietnamese had succeeded in tying up the forces of the Americans and distracting them from the preparations for the Tet offensive, which is why this came as a more surprise to the Americans than would otherwise have been the case. In this context, some experts are also considering the possibility that the North Vietnamese never really planned to take the Khe Sanh Combat Base, but only to tie up the largest possible number of American troops there.

Media and culture

In the American media, the coverage of the Battle of Khe Sanh took up about 25% of the total time of the coverage of the Vietnam War, on the television station CBS even more than 50%. The battle had a major impact on the image of war in the United States, but also in Europe. The media have often compared it with the Battle of Điện Biên Ph wurde. Khe Sanh was also listed by Barack Obama in his 2009 inaugural address.

Also on the art of the battle had some impact: In the song Born in the USA by Bruce Springsteen , the line "I had a brother at Khe Sanh" in the battle for the military base refers. The Australian rock band Cold Chisel also wrote a song about the battle, although very few Australian Defense Forces soldiers were directly involved. The battle for Khe Sanh is a symbol of the futile effort in Vietnam, because although the camp was successfully defended, it was abandoned a little later.

literature

- Gordon L. Rottman : Khe Sanh 1967-1968: Marines Battle for Vietnam's Vital Hilltop Base (Campaign). Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2005, ISBN 1-84176-863-4 .

- Robert Pisor: The End of the Line: The Siege of Khe Sanh. WW Norton & Co Inc, New York 1982, ISBN 0-393-01580-7 .

- Bernard C. Nalty: Air Power and the Fight for Khe Sanh. Government Reprints Press, Washington 2001, ISBN 1-931641-84-6 Air Power and the Fight for Khe Sanh ( Memento June 27, 2004 in the Internet Archive ) (online, PDF).

- Moyers S. Shore: The Battle for Khe Sanh. Government Reprints Press, Washington 2001, ISBN 1-931641-87-0 .

Web links

- The Battle of vietnam-war.info (Engl.)

- Khe Sanh Veterans Association (Engl.)

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Peter Brush: The Withdrawal from Khe Sanh . In: historynet.com . June 12, 2006. (English)

- ^ A b Peter Brush: Battle of Khe Sanh: Recounting the Battle's Casualties . In: historynet.com . June 26, 2007.

- ↑ a b Khe Sanh Chronology 1962–1972 ( Memento from January 15, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Khe Sanh Chronology 1962–1972 (engl.)

- ↑ Lang Vei at gruntonline.com (Engl.)

- ^ A b c Bernard C. Nalty: Air Power and the Fight for Khe Sanh. ISBN 978-1-410-22258-9 .

- ↑ Dave Powell's Hill 881S Collection . In: hmm-364.org . (English)

- ^ Operation Pegasus ( Memento of March 10, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Moyers S. Shore: The Battle for Khe Sanh. ISBN 978-1-780-39630-9 .

- ^ Barack Obama's Inaugural Address . In: Wikisource . January 20, 2009. (English)

Coordinates: 16 ° 39 ′ 19.6 ″ N , 106 ° 43 ′ 42.9 ″ E