Battle of Long Tan

| date | August 18, 1966 to August 21, 1966 |

|---|---|

| place | Long Tan, South Vietnam , Long Tân , Phước Tuy Province , South Vietnam |

| output | both opponents claim victory for their own side |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Commander | |

|

Major Harry Smith |

Nguyễn Thanh Hồng |

| Troop strength | |

| 108 men | 1500-2500 men |

| losses | |

Vietnam War

Battle of Tua Hai (1960) - Battle of Ap Bac (1963) - Battle of Nam Dong (1964) - Tonkin Incident (1964) - Operation Flaming Dart (1965) - Operation Rolling Thunder (1965-68) - Battle of Dong Xoai (1965) - Battle of the Ia Drang Valley (1965) - Operation Crimp (1966) - Operation Hastings (1966) - Battle of Long Tan (1966) - Operation Attleboro (1966) - Operation Cedar Falls (1967) - Battle around Hill 881 (1967) - Battle of Dak To (1967) - Battle of Khe Sanh (1968) - Tet Offensive (1968) - Battle of Huế (1968) - Operation Speedy Express (1968/69) - Operation Dewey Canyon ( 1969) - Battle of Hamburger Hill (1969) - Operation MENU (1969/70) - Operation Lam Son 719 (1971) - Battle of FSB Mary Ann (1971) - Battle of Quảng Trị (1972) - Operation Linebacker (1972) - Operation Linebacker II (1972) - Battle of Xuan Loc (1975) - Operation Frequent Wind (1975)

The Battle of Long Tan took place on 18 August 1966 on a rubber plantation in the province Phước Tuy near the city of Long Tan, about 95 kilometers from Saigon , now Ho Chi Minh City , on the south of the Republic of South Vietnam held . This resulted in a major encounter battle between the 1st Australian Task Force (1 ATF) and the combined forces of the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong . The approximately three and a half hour long firefight was considered by the ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) to be one of the most lossy and intense in its military history.

demolition

While the Australians carried out armed reconnaissance missions from their headquarters in Nui Dat shortly after their landing in April to June 1966 , 1,500 to 2,500 men of the 275th Viet Cong Regiment, a North Vietnamese regiment and the D445 battalion moved one to the vicinity of the area of operations Prepare the offensive for Nui Dat. On August 16, 1966, the VC and NVA armed forces were east of the rubber plantation of Long Tan and opened fire on the base in Nui Dat with mortars and light artillery on the night of August 16-17. 24 men were wounded, one of them fatal. The localized VC firing positions were then hit by Australian artillery batteries with counterfire. On August 17th, B Company of the 6th Battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment set out to track down the enemy. Around noon on August 18, the D Company (strength: 108 men) received the order to take part in the operation. In the afternoon the first smaller firefight with a VC rifle group developed. The Australians were shot at in the flank with handguns and anti-tank rifles ( RPG-7 ) and were suddenly confronted with a much stronger enemy. The D Company was held down by heavy fire and requested artillery support. The situation worsened significantly when a heavy monsoon rain set in, which severely reduced visibility and made coordinated combat operations difficult. The 275th VC Regiment and the D445 Battalion tried to enclose and destroy the Australians. After a few hours, the D Company ran out of ammunition and had to be removed from two UH-1B Iroquois helicopters from Squadron No. 9 RAAF are supplied from the air. Far inferior but supported by artillery barrages, the D Company fended off a regimental attack. At the same time, infantry and cavalry forces prepared from Nui Dat Camp as darkness fell to relieve the trapped D Company . The VC was forced to evade and regroup for a final attack. The Australians withdrew into a defensive position during the night in order to prepare a landing zone for their wounded to fly out. The next morning they managed to secure the site. They also found large numbers of dead in the area. The operation ended on August 21 with 18 of its own dead and 24 wounded. The opponent's losses were given as 245. The exact “body count” varied, however, depending on the sources (Australian data, MACV data versus reports from the VC and the NVA). Due to the unexpected severity of the fighting, the ATF long believed it had suffered defeat in the rubber plantation near Long Tan. However, the high number of enemy losses clearly spoke in favor of a victory over the enemy. Here, too, the battle was interpreted from different perspectives. On the one hand, the battle in the rubber plantation halted the advance of the VC / NVA on Nui Dat for an indefinite period of time; on the other hand, the successful ambush was seen as a military and political victory over the occupiers. From the perspective of the 275th Viet Cong Regiment, on the other hand, the Battle of Long Tan was a defeat, since it had not succeeded in destroying a much weaker enemy despite overwhelming superiority. The battle had not weakened the 275th VC Regiment, however, as it was able to attack the 18th ARVN division a short time later. The D445 battalion also had hardly any losses in its combat strength, as it was also involved a little later in skirmishes with the 11th Armored Cavalry Task Force. For a long time, a number of legends and anecdotes grew up about the Battle of Long Tan, its chain of command and its events, but these could not be officially confirmed.

Location

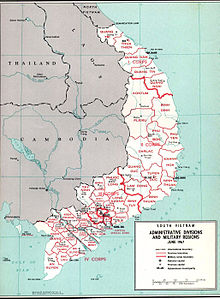

The operations took place in the South Vietnamese Phuoc Tuy Province. Starting from Nui Dat Camp, during Operation Hardihood, reconnaissance patrols were sent out early in the morning or in the evening within a radius of 12 kilometers. The guidance line here was Alpha, which was outside the range of the 4-kilometer radius of the VC mortar. Later they were extended to the 10-kilometer Bravo line, which could be swept by VC artillery. As soon as the Nui Dat military base began operating, residents of Long Phước and Long Hải villages were relocated within the Alpha Line. The aim of this was to establish a security zone and a "free-fire zone" for its own artillery. The VC should be prevented from observing the military camp. In addition, the enemy should be deprived of its base from the supporting population. These measures later proved to be counterproductive, as there was no longer any source of information for possible movements of the VC. In addition, it was now possible to attack Nui Dat without warning. From the Nui Dinh Hills, the enemy was still able to observe Nui Dat. In the first few nights, noises from VC patrols were heard more and more frequently in heavy rain. There were no clashes and the intensity of the enemy intelligence decreased, so that the AFT came to the conclusion that the VC had discontinued its intention to attack Nui Dat. On June 10, 1966, it was announced that a VC regiment would be on the march against Nui Dat and would already be ten kilometers away. In addition, there was occasional mortar fire against the base. During the night, the Australian artillery fired on movements along Route 2 without finding any casualties of the enemy the next day. The 6th Battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment (6th RAR), which had arrived from Vũng Tau on June 14, received a warning that an attack by at least four VC battalions was imminent.

Comparison of forces

1st Australian Task Force on August 18, 1966

- D Company, 6th RAR (6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment) - Major Harry Smith - 108 men

Combat Support:

- 1st Field Regiment, Royal Australian Artillery - Lieutenant Colonel Richmond Cubis

- 103rd Field Battery, RAA - 6 x 105mm L5 Pack Howitzers

- 105th Field Battery, RAA - 6 x 105mm L5 Pack Howitzers

- 161st Battery, Royal New Zealand Artillery - 6 x 105mm L5 Pack Howitzers - Major Harry Honnor

- A. Battery, US 2 / 35th Artillery Battalion - 6 x 155 mm M109 self-propelled howitzers - Captain Glen Eure

- No. 9 Squadron RAAF - 2 x UH-1B Iroquois helicopters

- 3 x US F4 phantoms

Substitute forces:

- A Company, 6th RAR (6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment) - Captain Charles Mollison

- 3 squads, 1st APC Squadron (Lieutenant Adrian Roberts) - 10 x M113

B Company command post, 6 RARs plus an additional platoon - Major Noel Ford

Operation Smithfield August 19-22, 1966

- 6 RAR Battle Group - Lieutenant Colonel Colin Townsend

- Command post 6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment

- A, B, C and D companies, 6 RAR

- D Company, 5th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment

Combat Support:

- 1st APC Squadron (with dues) - 2 MTW squads

- 161st Reconnaissance Flight - Bell H-13 Sioux light observation helicopter

- No. 9 Squadron RAAF-UH-1B Iroquois helicopters

5th Viet Cong Division

- Command post 5th VC Division - Colonel Nguyen Thanh Hong - 1500 to 2500 men

- 275th Regiment - Captain Nguyen Thoi Bung aka Ut Thoi - 1400 men (three battalions)

- D445 Mobile Provincial Battalion - Bui Quang Chanh aka Sau Chanh - 350 men, at least two companies, including C4 weapons Kp

- a regular battalion of the NVA

- Vo Thi Sau militia company - 80 men, mostly women (combat cleansing and recovery of the fallen / wounded)

D-Company vacancy list (selection)

- Major Harry Smith - Company Commander (born July 25, 1933 in Hobart, Tasmania )

- Captain HI McLean-Williams

- WO2 JW Kirby

- SSgt RR Gildersleeve

- Sgt W. O'Donnell

- Sgt DA Thomson

- Corporal PN Thomson

- LtCpl DA Spencer (†)

Attached Artillery Forward Observer Team / artillery observer

- Capt M. Stanley

- Bdr WG Walker

- LBdr NN Broomhall

10 platoon

- 2Lt GM Kendall

- Cpl TH Lea

- Pte CW Brown (†)

- Pte BD Firth (†)

- Pte BG Hornung (†)

- Pte IJ McGrath (†)

11 platoon

- 2Lt GC Sharp (†)

- LCpl BE Magnussen (†)

- Pte JE Berry (†)

- Pte RC Carne (†)

- Pte RM Eglinton (†)

- Pte DF Fabian (†)

- Pte AJ May (†)

12 platoon

- 2Lt DR Sabben

- Sgt J Todd (†)

- Pte DF Beahan (†)

- Pte GR Davis (†)

- Pte BD Forsyth († = b. Long Tan fallen)

Hostility

The main communist forces in Phước Tuy consisted of regiments 274 and 275 of the 5th VC division. It was under the command of Colonel Nguyen The Truyen and its command post was in the Mây Tào Mountains. Together with the NVA, their area of operation extended to the provinces Phước Tuy, Biên Hòa and Long Khánh. Their mission was to isolate the eastern provinces of Saigon and interrupt supplies on national routes 1 and 15, as well as provincial routes 2 and 23. The 5th NVA Division posed a major challenge for the ARVN armed forces, as its presence prevented the South Vietnamese government from controlling these provinces. In addition, numerous ambushes by the VC had already resulted in major losses at the ARVN. The 274th VC Regiment was the stronger and better equipped of the two formations. It had taken up its disposal space at Hát Dịch in the northwest of the Phước Tuy and consisted of the three battalions D800, D265 and D308 - about 2,000 men. The 275th VC Regiment operated out of the Mây Tào Mountains mainly in the east of the province. It was subordinate to Captain Nguyen Thoi Bung (also called "Ut Thoi") and consisted of the three battalions H421, H422 and H421 - around 1850 men. The VC units were supported by an artillery battalion, which was equipped with 75mm recoilless anti-tank rifles, 82mm mortars and 12.7mm heavy machine guns. In addition, a pioneer battalion, a telecommunications battalion and a pioneer reconnaissance battalion, as well as supplies and medical services. The local forces were combined in the D445 battalion, which normally operated south of Long Khánh. The D445 Btl was subordinate to Bui Quang Chanh (also called "Sau Chanh"), consisted of three rifle companies C1, C2 and C3 and the heavy company C4 and had a total strength of 550 men. The D445 Btl recruited mostly locally and also moved on family grounds, of which the soldiers had excellent local knowledge. The guerrilla forces (about 400 strong) fought in groups of five to 60 men. Two companies operated in the Châu Đốc district, one in Long Dat and a platoon in Xuyên Mộc. Overall, the Viet Cong could muster a team of 4500 men.

D445 battalion

For several weeks, the Australian signal reconnaissance SIGINT had cleared up the activity of a radio transmitter in the command post of the 275th VC Regiment and thus registered troop movements of the enemy to the west into the region north of Long Tân. Although deception could not be ruled out, several reconnaissance patrols were dispatched to locate the signal on the ground. On August 15, several patrols took place on the grounds of the rubber plantation. Although it was certain that stronger VC associations could be located, the search was unsuccessful. The patrols were then extended to the Nui Dinh area. There was evidence that Colonel Nguyen Thanh Hong planned and directed the operations of the 5th VC Division. It was reckoned with three battalions of the 275th NVA regiment (about 1400 men) and said D445 battalion. There was also evidence that the 274th NVA regiment had set up an ambush on Route 2 in order to attack the 11th Armored Cavallry Regiment "Blackhorse", which had received the order to support the Australians .

Australian operations

At the end of July 1966, SAS patrols had cleared up a larger VC formation east of Nui Dat, near the abandoned town of Long Tân. As a result, the Australians began a series of search and destroy operations in the area. On July 25, a fire fight developed between the C Company and the D445 battalion. In the course of an evasive maneuver by the B Company, the D445 Btl came to a deadlock and was driven out with heavy losses. In the days that followed, there were further clashes around Long Tân in which 13 Viet Cong soldiers were killed and 19 wounded. Three dead and 19 wounded among the Australians. Due to the expulsion of the civilian population and the fortress character of the surrounding villages, the area was considered secure by the 6th RAR. This turned out to be a misjudgment of the situation. In truth, regiments 274 and 275 were still very active and continued to destabilize this zone. There were increasing reports that the VC had returned to Long Tân, which was seen as an occasion for further search and destroy operations from July 29, 1966. When a large enemy force was reported approaching the Nui Dat base, Brigadier General Oliver David Jackson's Search and Destroy squads were immediately ordered back. An attack on Nui Dat was initially not confirmed and his request for support from the Second US Field Force was viewed as an overreaction. On August 5, 1966, the 6th RAR resumed operations along Route 2. This included the village of Binh Ba, which was a key tactical position for the movements of the VC in the north of Long Khánh Province. This also included Bà Rịa and Xuân Lộc. These were already dominated by the VC and with a population of 2100 men, taking it through the 6th RAR was seen as too complex and expensive. On August 9, 1966, Binh Ba was trapped by the Australians in the first light of day. In this operation also were armored M113 APCs, pioneers and artillery involved. Together with the South Vietnamese police, this area was systematically combed while the civilian population was supplied with medicine and food. The operation was extended to the villages of Dục Mỹ and Dục Trung. On August 10, the Binh Ba area was cleared and the operation was extended to the areas to the right and left of Route 2. On August 14, 1966, there was a firefight with a smaller VC squad, in which an Australian was killed, and on August 18, 1966, Route 2 was reopened for civilian traffic. As part of the overall operation, 17 Viet Cong were arrested and 77 other suspects. As the end result, a platoon of the Binh Ba guerrillas was completely crushed, the main VC forces weakened, the enemy infrastructure was permanently damaged and a number of villages were brought back under government control. By stationing an ARVN ranger company, permanent control should be exercised. This was an important step for the pacification of the Phước Tuy Province. However, as operations expanded to the Núi Dinh Hills, there were serious clashes with the D445 battalion. The continued need to secure Nui Dat increasingly weakened the fighting power of the Australians, as they had only two battalions instead of three. In addition, there were logistical problems that were exacerbated by the difficult sand dune terrain of Vũng Tau. In mid-August 1966, the Australian troops were already overworked by the heavy patrol activity during the day and night and a two-day rest and recreation program was ordered in Vũng Tau to restore combat strength and morale. At the same time, the 275th VC Regiment received orders from the 5th VC Division to march against Nui Dat.

Combat operations on the rubber plantation

The D Company began on August 18, 1966 to comb the area around the rubber plantation. At 3:40 p.m., a small group of Viet Cong came into contact with the enemy for the first time in a difficult section of terrain. Fire was opened on them at once. The Australians were still convinced that this would only be a fleeting contact. However, fire support was requested from the artillery. During a break in the fight, the opponent's first fallen were rescued. They did not wear black suits, carbines or repeating rifles, as is usual with the Viet Cong, but rather khaki uniforms and semi-automatic assault rifles, which they identified as members of the North Vietnamese army. The Australians did not draw any conclusions from their discovery and followed the fleeing troops. After the radio messages from D Company were evaluated at headquarters, the assumption was finally made that the main forces of the enemy had actually been encountered here. The D Company platoons had meanwhile moved further and further away from the company command post and were standing in front of them in isolation. The distances had increased continuously and the flanking sections were increasingly lost from sight. In addition, visual contact was lost in the thick vegetation.

At 4:08 p.m. the left flank of an Australian platoon was taken under heavy fire by the enemy with machine gun fire. This is where the first losses occurred. As soon as the platoon was in position, a second machine gun shot at it. When the platoon tried to shift its positions, grenade fire hit its flanks. As a result, the Australians were encircled, kept on the ground by enemy fire and in danger of being overrun. The exact position of the enemy could not yet be determined.

At this moment heavy monsoon rains set in, which made the battle extremely difficult for both sides and further reduced visibility. The 161st Battery of the Royal New Zealand Artillery provided fire support for the isolated train, but had great difficulty in determining the exact positions of the enemy due to a lack of fire control and target recognition. Gradually it became clear that the opponent was opposed not in terms of strength, as initially assumed, but in at least several company strengths. Despite heavy rain and artillery fire, the isolated train 11 managed to keep the Viet Cong from overruning them in the storm and burglary. At 4:22 p.m. another firing from the New Zealand artillery was requested. 20 minutes after the first contact with the enemy, 1/3 of platoon 11 was killed or wounded. Among them, platoon leader Second Lieutenant Gordon Sharp. Despite heavy resistance, train 11 was completely enclosed by the enemy. As a result of the intense fire fighting, e.g. Sometimes for up to four hours, the Australians gradually ran out of ammunition. The D-Company requested armed Chinook CH-47 helicopters to at least switch off the enemy mortar fire. Only heavy 155mm howitzers from the Americans silenced this. Train 10 was ordered to catch up with train 11 and come to the aid of the trapped comrades. The enemy tightened their grip with wave-like attacks, particularly on the two flanks to the north and south. An air strike with napalm was rejected again due to the bad weather and the artillery fire continued to relieve the trapped forces.

Its own artillery barrage prevented platoon 11 from being completely destroyed by the strongly superior enemy forces. When it got dark, Iroquois helicopters dropped ammunition so the trapped Australians could survive the night. The flights took place at treetop height under difficult combat conditions. At the same time, MTWs made their way from the headquarters in Nui Dat over muddy jungle slopes that had meanwhile been heavily softened by the rain to their own enclosed parts. With the help of their heavy machine guns, they were able to considerably reduce enemy pressure.

At midnight, the first helicopters (US Medical Chopper) landed to evacuate the trapped train from the air. The wounded were immediately taken to the Vung Tau military hospital.

On August 19, 1966, the heavily decimated D Company returned to the battlefield together with the A, B and C companies of the 6th RAR and the D company of the 5th RAR to rescue the wounded and fallen. However, it took until August 21, 1966 to completely secure the area and to clear it of any remaining enemy forces. The enemy was not pursued any further and all formations returned to the Nui Dat base. Operation Smithfield ended at 5:00 a.m. on August 21, 1966.

Chronology of events on August 18, 1966

- 16:08 p.m. Platoon 11 had enemy contact with at least two enemy machine guns. Two soldiers fell immediately on first contact and the left flank came under pressure immediately.

- 4:09 p.m. Platoon leader Sharp ordered his platoon to regroup in an L-shape in order to relieve the pressure on the left flank.

- 4:10 p.m. Sharp requested direct fire support from the artillery.

- 16:10 B Company was given the command to, grid square ready for further orders to keep 458,665th

- 4:10 p.m. Artillery observer Stanley alerted his own battery to be ready for the fire.

- At 4:15 p.m., a regimental fire mission was requested from all 24 guns in the regiment. At 4:20 p.m. Company Commander Harry Smith requested the same fire again with great force. Brigadier Jackson (ATF) was informed at the same time. At 4:22 p.m. the first impact of its own artillery took place.

- At 4:25 p.m. D Company reported enemy mortar fire and received permission from Major Smith to move its position up to 200 meters further northeast.

- 4:30 p.m. Train 11 was attacked from three sides.

- 16:33 clock driver Gordon Sharp († 22 years) fell, Sergeant Buick took over.

- 4:35 p.m. Communication to train 11 interrupted.

- 4:40 p.m. Train 10, which Train 11 was to come to the rescue, was taken under fire by the enemy itself.

- 4:50 p.m. onset of monsoon rain.

- 5:02 p.m. Smith called for an air strike and ammunition replenishment.

- 5:05 p.m. Train 10 was ordered back to the company positions, as it was not possible to reach Train 11 without suffering heavy losses.

- 5:05 pm The first MTWs arrived at Company A in Nui Dat. The riflemen mounted and waited for further orders.

- 5:09 p.m. Buick marked the enemy's positions with smoke grenades to enable the F4 Phantoms to recognize their target for the air strike. Due to the poor visibility, the air attack was canceled.

- 17:17 p.m. train 12 under Lt. Sabben left the company command room with only 20 men to relieve platoon 11.

- 5:17 pm Situation Report (SitRep) from Sgt Buick: The situation of train 11 is desperate. They would be trapped, suffer heavy losses and run out of ammunition.

- 5:25 p.m. Enemy forces of around 200 men appeared in front of the positions of train 10.

- 5:30 p.m. After a heated discussion between Jackson and Townsend, Company A and the MTWs are released for the relief of train 11. It was feared that A Company could also be ambushed.

- 5:35 p.m. Buick requested an artillery strike on its own position in dire straits. They only had ten men capable of fighting and hardly any ammunition of their own.

- 5:40 p.m. Lightning strikes from the monsoon weather led to gun failures.

- 5:50 p.m. Artillery cease fire so that the chopper ammunition could fly in

Conclusion

Vietcong and NVA

- 245 casualties (probably much higher, own casualties were rescued directly from the battlefield in accordance with Vietnamese custom, among other things to leave the enemy in the dark about the height of the "body count")

- 3 prisoners

- 350 wounded (according to estimates by the military intelligence service)

ANZAC

- 18 dead, 17 of them from D-Company (KIA - killed in action)

- 24 wounded (WIA - wounded in action)

Later investigations showed that the Australians had presumably faced an enemy superior force consisting of mixed troops of the Viet Cong and the regular North Vietnamese army in strength of 2500 men, which would correspond to an enemy ratio of 1:25.

aftermath

Radio Hanoi announced the aftermath of the Battle of Long Tan with war propaganda:

" The Australian mercenaries, who are no less husky and beefy than their allies, the US aggressors, have proved as good fresh targets for the South Vietnam Liberation Fighters. According to LPA [Liberation Press Agency], in two days ending August 18, the LAF [Liberation Armed Forces] wiped out over 500 Australian mercenaries in Baria Province. LPA reported: On August 18 in the coastal province of Baria, east of Saigon, the LAF wiped out almost completely one Battalion of Australian mercenaries in an ambush in Long Tan village. At 1500 hours that day, an Australian mercenary Battalion and a column of Armored cars fell into an ambush. Within the first few minutes the LAF fiercely attacked the enemy and made short work of two companies, set fire to three M113 armored cars, and drove the remnants into a corner of the battlefield. The LAF then concentrated their fire on them and heavily decimated the remaining company. 'The LAF shot down one of the US aircraft which went to the rescue of the battered Australians. "

The Battle of Long Tan had a profound effect on the war experience of Australians during the Vietnam War. For the Australians and New Zealanders, it was their bloodiest and most formative battle of the entire war.

" They were just walking toward us like zombies and everyone you knocked down there were two to take his place. It was like shooting ducks in a bloody shooting gallery. I would have killed at least 40 blokes that day. "

On May 28, 1968, the D-Company of the 6th RAR was praised by US President Lyndon Johnson for its bravery. Further honors took place when the company returned home.

Trivia

The Australian feature film “ Danger Close: The Battle of Long Tan ” from Red Dunes Studios, directed by Kriv Stenders , which was released in 2019, is about the dramatic processing of the Battle of Long Tan. The main characters are Travis Fimmel as Major Harry Smith, Luke Bracey as Sergeant Bob Buick, Richard Roxburgh as Brigadier David Jackson and Nicholas Hamilton as Private Noel Grimes.

Bibliography

- Terry Burstall: The Soldiers' Story: The Battle at Xa Long Tan Vietnam, August 18, 1966 . University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Queensland 1987, ISBN 0-7022-2002-7 .

- Terry Burstall: A Soldier Returns: A Long Tan Veteran Discovers the Other Side of Vietnam. University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Queensland 1990, ISBN 0-7022-2252-6 .

- David Cameron: The Battle of Long Tan: Australia's Four Hours of Hell in Vietnam . Penguin Random House, Melbourne 2016, ISBN 978-0-14-378639-9 .

- Robert Grandin: The Battle of Long Tan: As Told by the Commanders . Allen & Unwin, 2005, ISBN 1-74114-199-0 .

Web links

- "As it happened: Australia marks 50th anniversary of Long Tan battle". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. August 17, 2016 (en.)

- "Fitting Recognition for Long Tan Sacrifice". Army: The Soldiers' Newspaper. Canberra: Department of Defense. November 17, 2016, pp. 6–7 (en.)

- Battle of Long Tan, official homepage ; Battle of Long Tan (en.)

- Battle of Long Tan on ANZAC Portal (en.)

- The Battle of Long Tan: How 100 Australian soldiers held off 2,000 Viet Cong. ABC news. 18th August 2016

- Sam Worthington: Battle of Long Tan Documentation

Individual evidence

- ^ The battle over Long Tan's memory - a perspective from Viet Nam

- ↑ Viet Cong

- ^ North Vietnamese Army

- ↑ probably meant Air Cavallry

- ^ Army of Republic of Vietnam

- ^ Manning Details for August 18, 1966

- ↑ a b c Battle of Long Tan Timeline in The Morning Bulletin

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Death in the Rain - Battle of Long Tan. History Channel

- ^ Long Tan - Facts and Figures. Australia Great War

- ^ Long Tan Battlefield Aftermath

- ↑ The battle of Long Tan: Australia's four hours of hell in Vietnam by David W. Cameron - Book review

- ^ Long Tan Battlefield Aftermath

- ↑ Battle of Long Tan: Five defining characteristics of Australia's costliest Vietnam War battle. ABC News. 18th August 2016

- ↑ "Danger Close", official homepage of the film

- ↑ "Danger Close" on www.moviepilot.de

- ^ "Danger Close" - The Battle of Long Tan Movie

- ^ Battle of Long Tan. Penguin Publishing House