Liberation of Paris

Vehicles of the 2nd French Armored Division after the liberation of Paris on August 26, 1944 on the Champs-Élysées

| date | 19th bis 25. August 1944 |

|---|---|

| place | Paris , France |

| output | allied victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Omar Bradley , |

|

| Troop strength | |

|

2nd French Armored Division , 4th US Infantry Division , Resistance |

City occupation |

| losses | |

|

not exactly known |

not exactly known |

The liberation of Paris (French: Liberation de Paris ) took place during the Second World War during Operation Overlord towards the end of August 1944.

In the French capital, which has been occupied by German troops since June 1940, a general strike began in mid-August 1944 , which was followed by an open uprising by the French resistance fighters on August 19 . Allied associations advanced towards Paris to support it. After the rebels controlled most of the city and the first Allied troops had reached its center, the German city commander Dietrich von Choltitz surrendered on August 25, 1944, in disregard of Hitler's express orders, to French resistance forces under the command of Colonel Rol and the Allied troops the order of General Leclerc de Hauteclocque . The Mémorial Leclerc (closed 2018/2019) commemorates the events.

initial situation

On June 6, 1944, an Allied Expeditionary Force landed in Normandy as part of Operation Overlord under the command of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) led by US General Dwight D. Eisenhower , in order to relieve the Soviet Union in November 1943 to open the Second Front decided at the Tehran Conference . Until then, since 1941 on mainland Europe outside Italy (the Allies landed in Sicily in summer 1943 and in Calabria in September 1943 ), only the Red Army had resisted the Axis powers as a regular force . Then the Allied units were to advance further inland and liberate France. On August 15, 1944, as part of Operation Dragoon, troops also landed in Provence (southern France) and began a pincer movement against the German occupation forces.

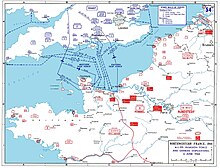

The Allied advance to the Seine

After two German armies were encircled by the Allies near Falaise , the German troops that had escaped there withdrew towards the Seine . On August 19, US General Eisenhower, commander in chief of the Allied forces, discussed the pursuit of the retreating enemy with his army group commanders. During this discussion the Allies resolved to wipe out the German armed forces west of the Seine.

To achieve this goal, General Bernard Montgomery, as commander of the SHAEF ground forces of the Canadian 1st Army and the 12th Army Group , ordered the northern and southern sides of the German-occupied area to be secured, while other units of the 12th Army Group headed north Should advance the estuary to stop the German retreat there. The 21st Army Group should first bring the Falaise pocket under Allied control and liberate the area from German soldiers.

This deployment of Allied units soon afterwards led to considerable confusion in the Allied supplies. Eisenhower announced on August 19: “ Rapid advances and consequent overlapping in attacks on a converging and fluent front. "(German:" Rapid advances and the resulting overlaps in the attacks on an approaching and flowing front. ")

On the German side, the units were regrouped: from the English Channel to Laigle the remains of the 7th Army , from there to Paris-West the remains of the 5th Panzer Army and the 1st Army near Paris and on the upper Seine .

Field Marshal General Walter Model , Commander in Chief in the West from August 16, 1944 to September 3, 1944, received orders on August 19 as follows:

- " 1. Prevention of the passage across the Seine down [south] of Paris, if necessary by bringing 2 SS = P [an] z [er]. = Brigades;

- 2. Prevention of the hostile. Advancing north on the west bank of the Seine, in such a way that, in the worst case, the 7th Army could be led back behind the lower Seine;

- 3. Fighting free of the connection between the barrier belt of Paris and the AOK 1 [Army High Command 1 (= 1st Army)] by tank units, assertion of the area forward Paris and thereby ensuring the return of the 19th Army . "

Parts of the 1st and 3rd US Army advanced northeast on the left bank of the Seine on August 20, whereupon the 3rd US Army built a bridgehead over the Seine at Mantes-Gassicourt on the same day and then with parts the army marched north towards Vernon . Parts of the 1st US Army reached the city of Évreux three days later, on August 23, and another two days later Elbeuf , which is about eleven miles southwest of Rouen . The British 2nd Army began its advance towards the Seine on August 20th and advanced to Louviers by August 26th . The 2nd Corps of the 1st Canadian Army reached the Seine on the same day and met with US units at Elbeuf. General Henry Crerar , commander of the Canadian 1st Army, had the second corps at his disposal advance towards the Seine near the English Channel . Despite heavy fighting at Pont-l'Évêque and Lisieux , the corps reached the Seine on August 27th.

From August 26th, the Allies locked the Germans in new pockets and traps between Elbeuf and Le Havre and attacked the fleeing units from the air with bombers and from the ground with tanks . German generals later stated that they were surprised to be able to transport anything across the Seine at all.

The fight for Paris

Originally, the Allied plans provided for bypassing the city and only conquering it later. However, the Parisian population as well as the Allied soldiers expected that the city would soon be liberated.

After the Parisian population could no longer pay for most of the food on the black market in 1944 , the number of starving people rose. The Parisians then joined the Resistance in increasing numbers . As an exception, three Germans did this, the soldiers of the Kriegsmarine Kurt Hälker and Hans Heisel as well as the employee of the foreign service Karl-Heinz Gerstner . They also informed their new comrades about intended arrests and Hitler's orders to destroy Parisian industry.

French resistance

After the rapid Allied advance towards Paris, the Paris underground, the gendarmerie and the police went on strike on August 10 (partly under pressure from the Resistance, partly voluntarily); from August 16, the postmen also went on strike. The Germans responded by shooting 35 young French people on the night of August 16 at the Carrefour des Cascades in the Bois de Boulogne . When more workers joined the strike movement, a general strike broke out on August 18, the day when all the resists were called upon to mobilize .

On the morning of August 19, resistance fighters spontaneously attacked German columns of cars driving on the Champs-Élysées. Disorganized and inadequately armed, they occupied police stations, ministries, newspaper offices and the Hôtel de Ville (town hall) . They used hunting rifles, old, captured or makeshift weapons such as Molotov cocktails .

On the evening of August 19, von Choltitz asked for a ceasefire in order to investigate the situation. He and representatives of the Resistance agreed a ceasefire until noon on August 23, so that German troops could be withdrawn west of Paris to the east without having to fight their way back. Some Resistance fighters took advantage of the situation to take the Ministry of the Interior (headquarters of the Gestapo ), the town hall and other public buildings.

Allied forces intervene

General de Gaulle, who has now come to France from Algiers, told General Eisenhower on August 21 that he was concerned that the extreme food shortage could lead to riot in Paris. He considered it necessary to liberate Paris with French and Allied troops as quickly as possible, even if there were some fighting and destruction in Paris.

De Gaulle nominated General Marie-Pierre Kœnig as military commander of Paris and instructed him to discuss the question of the liberation of Paris with Eisenhower. Eisenhower said after the conversation with Kœnig: “It looks now as if we'd be compelled to go into Paris. Bradley and his G-2 think we can and must walk in. "

On the evening of August 22nd, Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered General Omar Bradley to take Paris. After increasingly fierce fighting between resistance fighters and Germans, about three-quarters of Paris was in the hands of the Resistance on August 24th, but the center was still held by the Germans. The Allies gave the French 2nd Panzer Division under Major General Leclerc the order to advance into Paris. This division had been chosen at the request of the British and the United States because it was largely made up of soldiers from metropolitan France, while a large part of the Free French troops consisted of North and Black Africans. The division's three mechanized infantry battalions, made up of Tirailleurs sénégalais , were exchanged for French and Spanish volunteers. Leclerc's troops encountered isolated resistance during their advance from the southwest and lost around 300 men, 40 tanks and self-propelled howitzers, as well as more than 100 other vehicles. On the evening of August 24, Leclerc had a small column of tanks drive into town and advance to the town hall , which was under French control. This was "La Nueve" (Spanish: "The Ninth"), a unit of the free French armed forces consisting mainly of Spanish soldiers. Under the French commander Raymond Dronne, "La Nueve" was the first military unit to advance there; Since 2004 a plaque near the Hôtel de Ville has been commemorating these previously largely forgotten soldiers. On the morning of August 25th, Leclerc's division and the 4th US Infantry Division were in the center of Paris.

German surrender

Contrary to the express “ Führer order ”, according to which Paris should be defended and destroyed to the last man before it fell “into the hands of the enemy” (the order of August 23, 1944 ends with the sentence “Paris must not be allowed in or only as a field of rubble in the hand of the enemy will fall. ”), von Choltitz capitulated after initial resistance against the advancing resistance fighters and the Allies with the French 2nd Panzer Division at the head. He handed Paris almost unscathed on August 25, 1944 at around 2:45 p.m. to Henri Rol-Tanguy , the Paris leader of the Resistance units, and shortly afterwards to the French Major General Leclerc and General Bradley. On August 25th around 12:20 p.m. the tricolor was hoisted on the Eiffel Tower and a little later on the Arc de Triomphe .

On August 26, Charles de Gaulle , leader of the Armée française de la Liberation and the Comité français de la Liberation nationale (French Committee for National Liberation) , moved into the Ministry of War on Rue Saint-Dominique . Then de Gaulle gave a speech to the Parisians from the balcony of the town hall. He irritated many members of the Resistance when he thanked the gendarmerie for their support , not first to the fighters of the Forces françaises de l'intérieur , which had only changed sides on the last day. On the same day, a victory parade followed on the Avenue des Champs-Élysées , which was risky due to snipers still fighting in the city and possible German air raids.

A bookseller from Paris, Jean Galtier-Boissière, described scenes in Paris on August 25, 1944 as follows:

“An excited crowd huddles around the French tanks, which are decorated with flags and flowers. On every tank, on every armored vehicle, girls, women, boys and Fifis stand right next to the men in khaki overalls and kepi . The people lined the street, threw kisses, raised their clenched fists, and showed their enthusiasm for the liberators. "

On the night of August 26th to 27th, 111 aircraft of the Air Fleet dropped 3 bombs over the south of Paris. 593 buildings were destroyed or damaged; 213 people were killed and 914 wounded.

Eisenhower and Bradley arrived in Paris on August 27; on August 29, the 28th US Infantry Division - also on the Avenue des Champs-Élysées - held another victory parade. After the parade, the division went to Le Bourget Airport , 13 km northeast of Paris, and then drove on to Compiègne to fend off German counter-attacks.

For further information see: The advance to the Siegfried Line

Casualty numbers

In 1946 Adrien Dansette cites numbers or estimates of the victims of the liberation of the capital. 130 soldiers of the French 2nd Division Blindée , 532 French resistance fighters and around 2,800 civilians killed. Of the 177 police officers killed, 15 were executed by the Germans in Fort de Vincennes . The German casualties amounted to 3200 dead and about 12800 prisoners.

literature

- Martin Blumenson : United States Army in World War II - European Theater of Operations: Breakout and Pursuit. Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington DC 1961 ( Online )

- Victor Brooks: The Normandy Campaign: From D-Day to the Liberation of Paris . Da Capo Press, Cambridge, Mass. 2002, ISBN 0-306-81149-9 .

- Walther Flekl: Article Liberation . In: France Lexicon . Erich Schmidt, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-503-06184-3 , pp. 560-565 study edition, ibid. 2006.

- Joachim Ludewig: The German withdrawal from France 1944 (= individual publications on military history, Volume 39), published by the Military History Research Office , Rombach Verlag, 2nd edition 1994, ISBN 978-3-7930-0696-1 .

- Klaus-Jürgen Müller : The Liberation of Paris . In: Michael Salewski, Guntram Schulze-Wegener (ed.): War year 1944: In the large and in the small . Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-515-06674-8 .

- Allan Mitchell : Nazi Paris: The History of an Occupation, 1940-1944 . 2008, ISBN 978-1-84545-451-7 (Paperback 2010: 978-1845457860).

- Steven Zaloga Liberation of Paris 1944 - Patton's race for the Seine , Osprey, Oxford 2008 ISBN 978-1-84603-246-2 .

Web links

- The Liberation of Paris - France's official website

- De Gaulle's speech from the balcony of the Hôtel de Ville (English)

- Information (English)

- Chronicle of the Liberation of the City ( Memento of February 17, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ) (French)

- Information about the Battle of Paris on the side of World War II Database on Liberation of Paris (English)

- Original color film footage (10 min.): Www.winstonchurchill.org (the last two minutes)

- United States Army in World War II. European Theater of Operations. The Supreme Command: Contents (TOC)

- Chapter 13: Relations With the French, June-September 1944

Individual evidence

- ^ Forrest C. Pogue: United States Army in World War II - European Theater of Operations: The Supreme Command , p. 216; Retrieved July 31, 2006.

- ↑ Percy E. Schramm (Ed.): War Diary of the High Command of the Wehrmacht 1944–1945 , Part 1, ISBN 3-7637-5933-6 , p. 358.

- ^ Forrest C. Pogue: United States Army in World War II - European Theater of Operations: The Supreme Command . Cape. XI: The Breakout and Pursuit to the Seine (p. 217; see footnote 68)

- ↑ Between Collaboration and Resistance ( Memento of February 2, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF)

- ^ Forrest C. Pogue: The Supreme Command , p. 240.

- ^ Forrest C. Pogue: The Supreme Command , pp. 240 f.

- ^ Mike Thomson: Paris liberation made 'whites only'. BBC News, April 6, 2009, accessed August 17, 2014 .

- ↑ Zaloga, p. 32.

- ^ The Daily Beast online : Who Liberated Paris in August 1944?

- ^ Photo of the command

- ^ Hedley Paul Willmott, Robin Cross, Charles Messenger: The Second World War , ISBN 3-8067-2561-6 , p. 231.

- ↑ Ulf Balke: Der Luftkrieg 1941 - 1945 in Europa , Volume 2, P. 364.Bernard & Graefe Verlag 1990.

- ↑ Adrien Dansette, Histoire de la liberation de Paris, Paris, Fayard, 1946, ISBN 2-2620-1060-9 , pp. 301-302. (on-line)