Battle for Caen

| date | June 6 to August 15, 1944 |

|---|---|

| place | Normandy , France |

| output | allied victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

|

|

| Troop strength | |

|

2nd Army ( I Corps , VIII Corps, XII Corps, XXX Corps , Canadian II Corps) RAF USAAF |

5th Panzer Army ( I. SS Panzer Corps , II. SS Panzer Corps , XXXXVII. Panzer Corps, LXXXVI. Army Corps) |

| losses | |

|

not exactly known |

not exactly known |

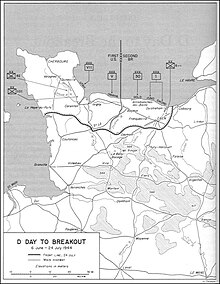

The Battle of Caen was a series of military offensive operations during World War II that occurred in northern France between June and August 1944.

The conquest of the strategically important French city of Caen was originally planned for the first days after the start of the landing in Normandy on June 6, 1944 as part of Operation Neptune . Despite a largely successful landing by the first Allied attack formations, the attempt to conquer Caen at the first attempt failed. The Allied commander Bernard Montgomery was therefore forced to make several attacks in the following months to conquer the city and to control its surrounding area. The area was defended by units of the German Wehrmacht and the Waffen SS .

In addition, the German commanders were to be diverted from the US sector by simulating a main attack on Caen in the British sector, thereby giving the American troops free scope for operations similar to lightning warfare . The following battles for Caen developed into a material battle and a positional war .

On July 9th and 10th the British and Canadians succeeded in conquering the northern and western parts of Caen. Another nine days later, on July 19, 1944, the entire city was under Allied control. The Allies then tried to break through the Caen-Falaise road to Falaise . The following fights are known as the Falaise Cauldron .

The repeated British attacks in the Caen area tied up important German troops. This enabled the American landing forces to expand the western part of the bridgehead and ultimately to achieve the decisive breakthrough in Operation Cobra at Saint-Lô . The battles for Caen were costly, but ultimately helped the Allies to establish a firm base in northern France, from which they first liberated Paris ( surrender on August 26, 1944 ) and later attacked the German Reich .

The medieval city of Caen and the surrounding villages, towns and also the area were largely destroyed by the Allied bombardment, artillery fire and the fighting. The reconstruction of the destroyed Caen lasted from 1948 to 1962.

background

initial situation

Even before the USA entered the war in December 1941, an involvement in the European theater of war was foreseeable. At the Washington Conference (December 22, 1941 to January 14, 1942) Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill agreed that a landing on the European continent via the Mediterranean , from Turkey to the Balkans , or in Western Europe would be required would. A confrontation with the German Wehrmacht was given priority over the Pacific War against Japan .

To relieve the Red Army , Joseph Stalin had urged the Western Allies to open a second front . At the Tehran Conference in November 1943, it was therefore decided to land in northern France ( Operation Overlord ) and southern France ( Operation Dragoon ). In contrast to Churchill, who allegedly wanted to forego Operation Anvil due to a lack of transport , Stalin favored the originally planned pincer movement. The Red Army had used this strategy successfully on several occasions. Meanwhile, the Americans also thought an invasion of southern France would make sense, as the ports of Toulon and Marseille would provide good supplies and supplies for the Allied troops in France. Finally, a simultaneous invasion of southern France was abandoned and began as Operation Dragoon on August 15, 1944.

At the Casablanca Conference , in the absence of Stalin, it was decided to establish a joint headquarters, the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force . Dwight D. Eisenhower took the lead as Supreme Allied Commander . His chief of staff was, under the designation Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander , the Lieutenant-General ( Lieutenant General ) Frederick E. Morgan , who then directed the planning for Operation Overlord. Bernard Montgomery received the command of the landing units . The Naval Forces commanded Admiral Bertram Ramsay and the Air Forces Air Chief Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory . The main objectives were to control the larger cities of Caen , Bayeux , Saint-Lô and Cherbourg .

Operation Neptune - Invasion of Normandy

On June 6, 1944, the so-called D-Day , Allied troops attacked the French Channel coast with a large force in the course of Operation Neptune . It comprised several thousand ships, around 2000 fighters and 1000 bombers . The troops landed over a length of 98 kilometers between Sainte-Mère-Église on the Cotentin peninsula in the west and Ouistreham in the east. The US 1st Army landed on the western beach sections of Utah and Omaha on June 6, the British-Canadian 2nd Army landed on the eastern ( Gold , Juno and Sword ) , a total of around 170,000 men. The fighting on Omaha Beach in particular turned out to be extremely bloody and costly for both sides.

On the evening of the day of the invasion, the Allies secured five landing heads with the support of paratroopers who had been dropped behind the landing front with heavy losses the night before. During Operation Tonga , British and Canadian paratroopers and commandos jumped from behind the Sword stretch of beach or were dropped off with gliders . They could surgically important bridges such as the Pegasus and Horsa Bridge and the artillery battery at Merville take, then keep it and thus cut off the supply of German associations and the approach performing amplification. With this they created a beachhead north of Caen, which was of advantage to the Allied troops in the battle for Caen.

In order to build a secured bridgehead, the nearest cities had to be captured and the landing forces had to join forces. Caen and the surrounding area offered good terrain for creating airfields . Caen also had a port that could be used to transport supplies to Normandy.

course

The capture of Caen had already been the target of the British 2nd Army on D-Day . The control of Caen and the surrounding area would have enabled the Allies to build runways for supply aircraft and to use the airfield at Carpiquet . In addition, the crossing of the River Orne would have been made easier by the capture of the city and its bridges.

However, since the British and Canadians did not succeed in bringing the city under their control in the first days of the invasion due to the strong German resistance, Montgomery ordered several attacks on Caen and its surroundings. These operations were also intended to serve the purpose of distracting the German Wehrmacht from the US sector and, accordingly, to simulate a main attack in the British sector.

Meanwhile, the French Resistance sabotaged strategically important key points of the German defense such as railroad lines or roads during the Allied operations.

The combat area consisted partly of a bocage landscape with many fields, small paths, rivers and streams that offered good defensive positions. Surviving Allied soldiers reported that every single field had to be conquered in fierce fighting. In addition, the terrain was very accessible for tanks, which was of great importance for the Allies as well as for the Germans.

Caen was extremely important for the coordination of the German 7th Army and 15th Army in the Pas-de-Calais department . If the Allies took Caen, it would be inevitable that German troops would withdraw from the Channel coast in order to maintain a connection between them. A retreat, however, was by no means in line with the ideas of Adolf Hitler , who had ordered every meter of land to be defended and held. For this reason, the Germans concentrated their forces in the area around Caen. They moved 150 heavy and 250 medium tanks to the Caen area, but only 50 medium tanks and 26 Panzerkampfwagen V Panther in the area of the American units.

The battle of Tilly-sur-Seulles (June 8th to 19th)

From June 8th to 19th, 1944, a battle broke out near Tilly-sur-Seulles between parts of the British XXX Corps and the German Panzer-Lehr Division , commonly known as the Battle of Tilly-sur-Seulles. Both parties fought fierce battles for the place and the front line. It was only when British units penetrated the largely destroyed place on the evening of June 18 and stayed there despite isolated German counter-attacks that Major General Fritz Bayerlein , commander of the tank training division, ordered his troops to withdraw from Tilly-sur-Seulles.

After the area had changed hands about 23 times, the British 50th Infantry Division managed to completely conquer the area on June 19. 76 villagers also lost their lives in the fighting, around 10% of the population.

The Panzer Lehrdivision had 190 tanks before the battle; thereafter only over 66. In addition to the tanks, the Germans also lost 5,500 men. Tilly-sur-Seulles has since been home to a British military cemetery and a museum commemorating the battle. A little further away is another military cemetery, the Jerusalem War Cemetery , the smallest military cemetery in Normandy.

Operation Perch (June 9-14)

The original plan for Operation Perch was that the British XXX. Corps should advance southeast of Caen. The intake of Caen should already be finished by this time. Since the Allied schedule was not adhered to, the plan of operations was changed. The 1st Corps was now to attack west of Caen, from the Orne bridgehead, two days later. Now Caen should be taken with the help of a forceps attack.

Both the attack of the XXX. Corps as well as that of the 1st Corps were slow. The I. Corps, which fought primarily against the German 21st Panzer Division , broke off its attack on June 12th without much success. In order to support the British attacks, Canadian troops now also attacked. Parts of the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division attacked positions of the 12th SS Panzer Division "Hitler Youth" . The destination was the city of Le Mesnil-Patry. The Canadian advance failed with heavy losses and was canceled. West of Caen, meanwhile, a favorable opportunity arose for the British associations. The 1st US Infantry Division pushed back the badly battered 352nd Infantry Division , thereby exposing the western flank of the German Panzer Lehr Division . Montgomery then changed the plan of Operation Perch to attack the Panzer Lehr Division and take the town of Villers-Bocage and other nearby locations. For this, the British 7th Panzer Division was withdrawn from the fighting at Tilly-sur-Seulles and used in the direction of the gap that had arisen. This would have made the position of the Panzer Lehr Division untenable.

In the early hours of June 13th, British units of the 22nd Panzer Brigade took the town of Villers-Bocage. Parts of the nearby heavy SS Panzer Division 101 under the command of Michael Wittmann , which was on the way to secure the road N 175 south of Caen near Villers-Bocage, attacked the British units. In the ensuing battle, known as the " Battle of Villers-Bocage ", the British lost 20 Cromwell tanks , four Sherman Fireflys , a number of Stuarts and over 30 half-tracks and Bren Gun Carriers .

After this incident, other German tank units advanced on Villers-Bocage, but lost some of their Tiger tanks to the now better prepared Allies. On the German side ten of 25 tanks were lost during this battle, on the Allies 30 tanks and more than 30 lightly armored vehicles out of a total of 200. Without any military necessity and despite the successfully repulsed counter-attacks, the British commanders now ordered the withdrawal of the 7th Panzer Division, which resulted in the opportunity to flank German units being wasted.

On June 14th, after withdrawing from Villers-Bocage, the 7th Panzer Division took up defensive positions near Amayé-sur-Seulles. In the meantime, the British 50th Infantry Division renewed its attack on the positions of the Panzer-Lehr Division, which now saw itself threatened from several directions. However, a breakthrough through the German lines did not succeed. Thereupon it was decided to withdraw the 7th Panzer Division completely and to straighten the front line. Operation Perch was over.

The failure of Operation Perch put an end to "mobile" warfare in the Caen area. This was followed by a series of Allied advances in pieces to secure space, which was urgently needed in order to be able to bring more troops and material into the bridgehead. The fighting in the eastern area of Normandy now turned into a kind of attrition battle. For the failure of the operation on the Allied side, the commander of the 7th Panzer Division George Erskine and the commanding general of the XXX. Corps Gerard Bucknall blamed.

Michael Wittmann was celebrated by German propaganda for his work at Villers-Bocage as a war hero and suggested by Josef Dietrich for the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords . On June 25th, the order was conferred by Adolf Hitler in Berchtesgaden .

On June 14th and 15th, 337 Royal Air Force aircraft attacked German troops and vehicles at Aunay-sur-Odon and Évrecy near Caen. The background to this quickly carried out attack was a detailed report by the Allied reconnaissance of German units and their positions. Clear weather enabled the RAF to successfully bomb both targets without losses of its own.

Operation Epsom (June 25-30)

Eleven days after Operation Perch, the Allies began Operation Epsom after they had gathered and formed, but were held up by a storm between June 19 and 22.

The VIII. Corps under Lieutenant General Richard O'Connor , consisting of Canadian and Scottish units, was supposed to cross the River Odon west of Caen and form a bridgehead, with the help of which the encirclement of the city should be made possible. O'Connor were made available for the operation 60,000 soldiers, over 700 guns and about 600 tanks, most of whom, however, had little combat experience. Preparatory attacks by units of the I. Corps and the XXX. Corps should support the main attack. East of the main thrust, the British 51st (Highland) Division attacked the positions of the 21st Panzer Division. The attack aimed to tie the German units there. West of the planned main thrust attacked the 49th Infantry Division and the 8th Panzer Brigade in order to take the heights there. This was intended to cover the flank of the attack.

Bad weather conditions and failed preparatory attacks made the Allied attack more difficult. The Allied artillery supported the advance with a fire roller . On June 26th, the Allied bomber fleet in England was prevented from air support due to bad weather. The Allied attacks were mostly stopped by SS and Wehrmacht units. Most of the towns occupied by the Allies could not be held. After heavy fighting, the Allies took and secured Hill 112.

Because of the strong German resistance, the Allies succeeded in taking local targets by the evening of June 30, 1944, but the bridgehead over the Odon had to be cleared again. The VIII Corps lost an estimated 4020 soldiers in the fighting. General Foulkes of Canada's 2nd Infantry Division wrote: “ When we went into action at Caen and Falaise, we found that when we encountered battle-tested German troops, we were no match for them. Without our air and artillery support, we would not have been able to prevail. "

A Royal Air Force bomber formation comprising 266 aircraft was ordered on June 30, 1944 to bomb an intersection in Villers-Bocage in order to prevent an attack by two German armored divisions of the II SS, which had just arrived in Normandy, which was predicted for the night of July 1 -Panzerkorps to prevent the seam of the Allied armies. The commander of the bomber association instructed his pilots to go down to 1200 meters to see markings in the smoke and in the turbulent earth. 1,100 tons of bombs were dropped, two planes were lost and the German attack was prevented.

Operation Windsor (July 4-5)

Operation Windsor was originally scheduled for June 30th. The operation was planned in combination with Operation Epsom. Since this did not go according to plan, “Windsor” was postponed for a few days. Finally, Canadian units, namely the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division under Rod Keller , received the order on July 4, 1944, to capture the airfield at Carpiquet, a few kilometers west of Caen . The airfield should have been captured on D-Day, but this failed.

The village and the airfield were defended by grenadiers from the 12th SS Panzer Division "Hitler Youth" . Due to the importance of the airfield, the defensive positions were well developed. The airfield was fortified by reinforced concrete bunkers, machine gun towers and underground passages, 7.5 cm anti-tank guns and 20 mm anti-aircraft guns. Furthermore, the area was surrounded by minefields and barbed wire entrenchments. The Canadian troops were informed of the defenses by the Resistance before the attack.

On the German side, there was a weakened infantry battalion in action, supported by 15 tanks and six 8.8 cm guns . Four infantry battalions fought on the Canadian side, supported by armored forces of two battalions, plus more than 700 pipes and ships as artillery support. A Hawker Typhoon squadron was also available as support.

The attack began at 5 a.m. with artillery raids from both sides. The Allied artillery bombed Carpiquet , while the German responded and took the presumed advance directions of the Canadian soldiers under fire. The first companies of the Canadian attack were hit by German fire. It took the North Shore and Chaudière regiments on Carpiquet several hours to clear the defenders of the village. An understaffed grenadier company of around 50 men offered bitter resistance in house-to-house fighting and was only overpowered by the use of tanks. Further troop movements were severely hampered by the 8.8 cm anti-aircraft guns that were positioned east of Carpiquet. The attacks of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles from the west, which led over open terrain, were similarly severe when German troops from the southern hangars opened fire. German tanks prevented the Allied tanks from advancing, so the Canadian infantry were left on their own. After some Shermans had been eliminated, the soldiers of the Royal Winnipeg Regiment withdrew.

For the second phase of the attack, the Queen's Own Rifles were deployed . They took up position northwest of the airfield. The Winnipegs were now ordered to attack again in the direction of the airfield, supported by artillery and armored vehicles. This time they reached the outer hangars but were unable to capture them. Since this failure prevented the use of the Queen's Own Rifles , Blackadder ordered the attack to cease at 9 p.m.

The Canadian troops were able to take Carpiquet and occupy the undefended hangars in the north of the airfield. The remaining hangars and the control tower remained in German hands. As a result, Operation Windsor was an operational failure. The Canadian associations lost 377 men that day, the North Shore and Winnipeg had the largest losses with 132 dead each. Tank losses are only known from the 10th Armored Regiment and are given as 17. The units of the 12th SS Division suffered 155 losses.

Operation Charnwood (July 7-9)

The Allied plan envisaged attacking the German positions north of Caen with area bombing in order to demoralize the defenders and raise the morale of their own troops.

Meanwhile, on July 7, 1944, the Wehrmacht command staff issued the following order (note: the 12th SS Panzer Division was under the direct command of Adolf Hitler up to this point):

- "1. Holding the current front, […] clearing the 12th SS-P [an] z [er] div [ision] and replacing the worn-out inf [anterie] divisions with fresh ones; "[...]

- "9. Deployment of the entire Org [anisation] Todt "(construction organization for military installations) [...]

The commander of the division SS-Oberführer Kurt Meyer commented that it was the order to die in Caen.

After the Allies took some time to rearrange themselves and meet logistical requirements, Operation Charnwood began on July 7, 1944.

The Canadian 1st and British 2nd Armies with about 115,000 men were stuck near villages north of Caen held by German units, which is why the RAF initially planned to fly their attack on the villages, but then because of the dangerous proximity to their own Ground troops failed. The area to be bombed was then moved further towards Caen. Around 450 RAF Lancaster and Halifax bombers flew to the target area on July 7 at around 10 p.m. on a clear day, dropping around 2,300 tons of bombs. The bombardment did little damage to the German units, but all the more to the northern suburbs of the city, which were largely destroyed, and the French civilians, of whom around 3,000 died. After the Germans succeeded in shooting down an Allied aircraft with an anti- aircraft gun , three others later crashed over Allied airspace. In addition to the bombardment, ship artillery fired on the city from the beaches.

The author Alexander McKee said the following about the bombing on July 7th: “ The 2,500 tons bombs did not distinguish in any way between friend and foe. If the British commanders believed that they had intimidated the Germans by killing the French, they were very much mistaken. "

The intended demoralizing effect was small, as the ground attack did not take place immediately after the bombing, but rather the next morning, July 8th, at 4:30 a.m. The resulting mountains of rubble also made the use of tanks difficult. Later, when the city was captured, it was found that there were neither German artillery nor tanks nor dead people in the target area.

At the end of July 8th, the Allied troops had fought their way forward only one kilometer. After the German troops had largely withdrawn from the north and west as well as the center of the city on the morning of July 9th, Allied troops moved into the northern end of Caen, but were stopped by snipers as they advanced . At 6 p.m. on July 9th, the first units reached the river Orne in Caen. On the evening of July 9th and 10th, the Allies then moved into the city center. Pioneers were tasked with repairing the bridges over the Orne and clearing debris out of the way. The pioneer Arthur Wilkes described the state of the city as follows: “ Mountains of rubble, [about] 20 or 30 feet [≈ 6 or 9 m] high [...] the dead lay everywhere. “In the war diary of the 1st Battalion King's Own Scottish Borderers , an entry for July 9th says: Life slowly stirred in the houses that had stood still when the [French] civilians realized that we had conquered the city. They came out running with glasses and bottles of wine [from their houses]. Many residents of Caen were dead or homeless after the operation ended.

Operation Charnwood missed its goal of conquering Caen. The north and west of the city were occupied, but the eastern part of the city and the suburbs to the east, where the Colombelles steel works (with high observation posts) were located, remained in German hands. It took about nine more days before the southern and eastern districts, as well as the area and suburbs south and east of the city, were conquered by the British and Canadians on July 19. Strategically, however, the operation was a success, because the Germans now suspected that the main Allied attack would take place in the British sector of the front, which was not the case (see Operation Cobra ). Ultimately, this deception of the German defenders helped the Allies win in Normandy.

Operation Jupiter (July 10-11)

The 8th British Corps under Richard O'Connor tried again to expand the bridgehead at Caen. The 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division under Major General Ivor Thomas was then supposed to recapture "Hill 112" from the Germans on July 10 during Operation Jupiter, which had already been held for a short time during Operation Epsom. The elevation around this point, located between the Orne and Odon rivers , was viewed by both sides as crucial. In the first phase, the Allies should conquer Hill 112, Fontaine-Étoupefour and Éterville , and in the second defensive position should also move Hill 112 and conquer the town of Maltot . Later, the units were to advance eastwards towards Orne.

The 43rd Division was reinforced by several additional brigades for this operation. In total, Major General Thomas had 13 infantry battalions and 5 tank battalions available. In addition, several artillery units were provided by other divisions for the attack, a total of over 300 pipes. On the German side, several parts of various Waffen SS units were involved. The northeast of the hill in the Maltot area was covered by some units of the 1st SS Panzer Division "Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler" ; these were supported by 30 tanks from the 12th SS Panzer Division "Hitler Youth" . Securing the ridge and the areas north of it was the task of the 10th SS Panzer Division “Frundsberg” . Parts of the 9th SS Panzer Division "Hohenstaufen" acted as reserves during the operation.

At 4:55 a.m., the British artillery opened fire on German positions. The British infantry, along with supporting Churchill tanks, began their advance towards the ridge. For their part, the German units responded with artillery fire, including 8.8 cm cannons and smoke launchers. The British troops made slow progress towards Hill 112. Meanwhile, 20 Tigers of the heavy SS Panzer Division 102 were preparing for a counterattack southeast of the ridge . Some Panzer IV and Sturmgeschütz III of the "Frundsberg" division were also preparing for a counterattack between hills 112 and 113. Most of the British tanks were destroyed in these counter attacks. The British attempts to secure the southern side of the hill were thus repulsed; the German troops did not succeed in retaking the north side of the hill. The British then renewed their attack with fresh forces and artillery support. The Germans again responded with counter-attacks. The fighting over the hill was now fierce on both sides. There was a stalemate on the evening of July 10th. Associations on both sides were only a few hundred meters apart and buried.

In addition to the advance on the ridge itself, the British units launched attacks further north. In the morning hours they took both the Château de Fontaine-Henry and, a few hours later, Éterville further west. Around 10 a.m., Maltot was also in British hands. Half an hour later, British troops in Maltot reported that twelve of their Churchill tanks had been knocked out. Some Tiger tanks, supported by grenadiers from the SS “Leibstandarte” division, attacked the village and finally took it again. Another British battalion was sent to Maltot in the late afternoon. This advance failed with high losses; the rest of the attackers were wiped out by another German attack late in the evening. By nightfall, the British troops had been pushed back to Éterville.

The first day of Operation Jupiter ended for the 43rd Wessex Division with just over 1,000 casualties and 43 lost tanks. The attack on the ridge brought terrain gains, but German troops were still buried in the area. Fontaine-Étoupefour and Éterville about three kilometers north of the ridge were in British hands. Maltot east of the ridge was lost again to German counterattacks. The front line on the night of July 11th ran roughly from Éterville to Fontaine-Étoupefour and then south towards Hill 112.

On the evening of July 10th, Colonel Sylvester Stadler of the 9th SS Division undertook reconnaissance missions to prepare a major counterattack. The aim of the counter-attacks planned for July 11th was the recapture of Éterville and Fontaine-Étoupefour by forces of the 1st SS Division and the pushing back of the British forces from the ridge by parts of the 9th and 10th SS Division.

During the night there were constant minor skirmishes between German and British troops. Two German battalions attacked again in the direction of Éterville during the night. The place was now fiercely contested and changed hands several times. Scottish associations took up positions there in the early hours of the morning. Around noon on July 11th, soldiers of the Leibstandarte with assault gun support took Éterville, and around 2 p.m. they lost it again. By the end of the day, the outskirts were taken again by German troops. The front line of the Leibstandarte was restored by evening and ran from Maltot north to Louvigny near Caen. The night of July 11th was marked by artillery fire on both sides at Hill 112. The British battalion at the top of the hill was reinforced by 15 Sherman tanks that night. At around 6 a.m., German grenadiers, supported by a few tigers, attacked the hill from the south. The defenders were forced to withdraw north towards the Odontal valley. The summit of the hill 112 remained no man's land for the time being. The British forces were reorganized and made another attempt to take the hill, but were thrown back by another German counterattack. Operation Jupiter was now over.

Operation Jupiter ended with very little gain in space. The attackers' losses are estimated at just over 2,000 men. On the first day of the operation, 43 tanks were reported lost. The tank losses for the second day are uncertain. In addition to the small gain in space, the fact that it tied up German forces can be positively credited to the operation. The 9th SS Division, for example, was about to break away from the front in order to form an operational reserve. This was delayed by the British attacks. Since the Wehrmacht, unlike the Allies, lacked armored forces, this can be viewed as a strategic advantage. Operationally, Jupiter was a costly failure.

Operation Goodwood (July 18-20)

preparation

At a meeting with Field Marshal Montgomery on July 10, 1944, the commander of the 2nd Army, General Miles Dempsey , proposed the plan for Operation Goodwood . On the same day, Montgomery also approved Operation Cobra .

By mid-July 1944 the British had brought 2,250 medium and 400 light tanks in three tank divisions and numerous independent tank brigades to Normandy. Since the 2nd Army could afford to lose tanks, but not soldiers, a plan was drawn up to break through the German positions east of Caen with several tank divisions and advance into the southern hinterland of Caen. The Canadian II Corps was supposed to take the part of Caen still held by the Germans. This part of the operation was codenamed Operation Atlantic . Operation Goodwood was scheduled to begin on July 18, two days before the US Operation Cobra was scheduled to begin. Operation Cobra, however, didn't begin until July 25th.

Although it was expected to be a costly operation, Dempsey believed the British had a good chance of breakthrough. The main armed forces were to be the armored divisions of the British VIII Corps under General O'Connor. Around 700 guns were supposed to facilitate the attack beforehand with around 250,000 rounds. Furthermore, RAF bomber formations were planned for three targets - Colombelles-Mondeville, Toufreville-Emiéville and Cagny.

The goal was to conquer Bras , Hubert-Folie , Verrières , Fontenay , Garcelles-Secqueville , Cagny and Vimont . Another goal was to push the Germans back from the Bourgebus ridge. Canadian units were to secure the eastern flank and British infantry the western flank.

Meanwhile, the commander-in-chief of German Army Group B , Erwin Rommel , was wounded by Allied low-flyers on July 17 and brought to Germany to recover. He was then replaced on July 19 by General Field Marshal Günther von Kluge .

execution

On July 18, 1944, an Allied force of 942 aircraft, consisting of bombers and fighters, was tasked with attacking five villages in the area east of Caen to facilitate Operation Goodwood. The attacks took place at dusk in the morning of the day and in good weather conditions. Four of the targets were sufficiently marked by scout planes, with the fifth target the bomber crews had to find the target by another route. Supported by American bombers and fighters, the British planes dropped around 6,800 tons of bombs over the villages and the surrounding area. Two German units 16 Luftwaffe Field Division of the Air Force and the 21st Panzer Division , met the bombardment compared to the remaining German units very hard. A total of six Allied aircraft were shot down by German anti-aircraft guns and other ground troops.

A Welsh soldier described the air operation:

“The entire northern sky, as far as the eye could see, was filled with them [the bombers] - wave upon wave, one upon the other, expanding east and west, so that one thought it would go no further. Everyone had now left their vehicle and stared in amazement [into the sky] until the last wave of bombers had dropped their bombs and started the return flight. After that, the guns began to complete the work of the bombers with increasingly louder gunfire. "

The three Allied armored divisions had to overcome water hazards and a minefield to get to their starting position. The river Orne and the Caen canal ran behind the British front, and thus presented obstacles is to get ahead. Six small bridges were present for the 8000 vehicles, including tanks, the artillery , motorized infantry, the pioneers and the supply vehicles on the Bring rivers. It was obvious that traffic chaos would follow. Dempsey's proposed solution was disastrous - he instructed his corps commander O'Connor to pull the tanks up and leave everything else, including infantry, engineers, and artillery on the other side until all the tanks had crossed the river.

After the bridges were crossed, a British minefield that had been laid just days before by the 51st (Highland) Division had to be overcome. The minefield consisted of a mixture of tank and anti-personnel mines . This obstacle could have been cleared with massive engineer support before the battle. However, since the Germans were able to observe the minefield from the steelworks in the German-occupied Caen suburb of Colombelles, a large-scale mine clearing would have made them aware of the impending attack.

One of the Allies' mistakes was that they forgave the surprise effect. The many tanks were slowed down by the narrow bridges and the minefield. By deciphering Allied messages, the Germans had also been well informed about the time and place of the attack since July 15, so they reinforced their defenses. In addition, the fire support was poor. The artillery units remained west of the Orne, so that the German main defense positions at the Bourgebus ridge were not in their range of fire. There was also insufficient coordination between the field artillery and the tanks. In addition, the site was badly chosen. There were many small villages in the area, each with a small German garrison stationed and connected by tunnels. There were also many observation posts in the attack area, which could monitor the Allied progress. The ridge was also equipped with numerous German resistance nests , who had heavy weapons such as machine guns at their disposal, which had a clear field of fire.

The German artillery on the Bourgebus ridge at Cagny and at Emieville was not weakened by air or artillery support. From these places the Germans had a clear field of fire on the Allied units. The Germans had positioned the 16th Air Force Field Division and the 346th Infantry Division in front of the ridge. Behind it were anti-tank guns of the 21st Panzer Division on the sloping slope in massive stone houses, whose fields of fire overlapped and which were supported by infantry. 78 8.8 cm anti-aircraft guns were posted on the ridge that could destroy a Sherman with one shot. On the rear slope there were three combat groups, each consisting of 40 tanks and an armored infantry regiment, and further back artillery reserves were ready. The engineers of the 51st (Highland) Division cleared the minefield two nights before the attack, leaving 17 corridors the width of a tank cleared.

Another reason for the Allied defeat was the excessive demands of the British 11th Armored Division: Although she was the unit that led the attack, the division also the task of the villages had to clean on the front lines, namely Cuverville and Démouville . These should then be secured by the following units. The division's armored units eventually attacked the ridge while the infantry battalions cleared the villages. This slowed down the process and prevented meaningful cooperation.

The majority of the Allied formations gained territory only slowly. The 29th Panzer Brigade of the 11th Panzer Division - the most active unit of the Allies that day - had, however, already conquered almost eleven kilometers by noon.

When the Caen-Vimont railway was reached around 9:30 a.m. on July 18, the Germans had recovered from the bombing. Twelve Allied tanks were destroyed when an 8.8 cm anti-aircraft gun fired at them multiple times. The Allies advanced slowly and crossed the railway line to approach the Bourgebus ridge, where they encountered formations of the 21st Panzer Division, the 1st SS Panzer Division and numerous artillery pieces. For most of the day only the 29th Panzer Brigade attacked the German positions without artillery support. The infantry brigade was busy cleaning up two villages behind the tank brigade. The remaining two armored divisions were still passing the bridges or the minefield. At dusk, only one tank battalion of the British 7th Panzer Division fought , while most of the remaining tank formations had to remain at the Orne until 10 p.m. on July 18.

Individual tank battalions fought unsupported and one by one instead of fighting together. Most of the land gain was made on the morning of July 18th. Until July 19, the city of Caen was also largely under Allied control.

The Germans began a counterattack on the afternoon of July 18th, which lasted until July 20th. Montgomery broke off the operation on July 20, as 6,000 soldiers had already dropped out and around 400 tanks had been lost.

Effects

The operation ended to the detriment of the Allies. They lost an estimated 400 tanks and around 5,500 British and Canadian soldiers. The Germans held their most important positions with a loss of 109 tanks, which, in contrast to the Allies, was high for them, as they could hardly replace the losses. Tactically , the operation was a defeat for the Allies, but strategically the operation managed to make the Germans suspect the main Allied attack was now even more in the British sector.

This deception made it easier for the Americans to succeed in Operation Cobra. The Germans concentrated in the British sector and also expected a second, even larger invasion on the Strait of Calais due to Operation Fortitude .

Operation Spring (July 25-27)

At a conference on July 22, 1944, Operation Spring was decided, which should begin on July 25, under the orders of the Canadian General Guy Simonds . The aim of the operation was, among other things, the conquest of the high plateau at Cramesnil and La Bruyers , about five kilometers south of Bourgebous , by the II. Canadian Corps. The operation was to be carried out simultaneously with the American offensive further west.

Two Canadian infantry divisions were to attack, following which advancing armored divisions were to break through the gap created by the infantry and advance further to capture more distant targets. The Canadian 2nd Infantry Division under Major General Foulkes was to advance on the right and the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division under General Keller on the left. The operation should consist of three interconnected parts. First the line May-sur-Orne - Verrières - Tilly-la-Campagne , then the line Fontenay-le-Marmion - Roquancourt and the high plateau should be conquered. If the breakthrough through the German lines were successful, armored forces should advance on the Caen- Falaise road.

As the German commanders suspected further major attacks in the British sector, additional troops were brought into the Caen-Falaise area. According to the OKW report , the bringing in of the forces was essentially complete on June 25th . Therefore, the Germans had five armored divisions and various infantry units stationed in the area. This large concentration of formations with high combat value made an Allied breakthrough at this point very unlikely.

On the evening before the attack, 60 medium bombers flew a preparatory attack on German positions, which was severely hindered by German flak fire. The Canadian attack began at 3:30 a.m. on the morning of July 25th with the advance of the North Nova Scotia Highlanders of Canada's 3rd Infantry Division. The attack was to be supported by artificial moonlight: spotlights illuminated the cloud cover in order to illuminate the positions of the defenders with the reflected light. Since the attacking infantry could also be seen better at the same time, the usefulness of this action is questionable.

The operation did not achieve the goals set beforehand, but it managed to capture and hold Verrières , which was a good tactical position. The location at a high point made it possible to overlook a large area. It was also Tilly-la-Campagne conquered. The operation was one of the Canadians' most casualties in World War II; they lost around 1,500 men.

At the same time as the advances of the other allies, the US troops attempted to break out of their bridgehead at Saint-Lô on July 25 , which in the following days advanced in the west to cut off the Cotentin peninsula as far as Avranches . With Operation Cobra, the US units in the west of Normandy, after an initial delay, quickly broke through the German front and then swung to the east, which finally led to the Falaise pocket with the help of the British and Canadians fighting north . The unforeseen great success of the operation led to a change of plan by Montgomery on August 4th, which broke off a further advance west to the Atlantic ports in favor of a rapid advance to the east. Operation Cobra clearly marks the transition from positional warfare to war of movement and was the beginning of the Allied forwards rapid advance eastwards through northern France.

Operation Bluecoat (July 30th to August 7th)

Montgomery instructed the Commander in Chief of the British 2nd Army Dempsey, in the course of Operation Bluecoat with Canadian support, to drive the German troops south or southwest of Caen in order to keep them away from the American sector. The reason was a German action aimed at creating supplies and support for their troops in front of the American sector.

The operation began on July 29, 1944 south of Caumont . Despite the previous artillery fire, the British and Canadians did not succeed in achieving a breakthrough, as the Germans had placed their minefields well and otherwise offered strong resistance. The area was well suited for defense because of the many hedges and other coverings, which made the advance even more difficult for the Allies.

It was only when parts of the British 11th Panzer Division found a gap in the German defense lines that the Allied units were able to break through and advance to the city of Vire, which is important for the German defense . They soon had the city completely in their hands, which had burned to the ground because of the Allied bombing and German explosions. The British also captured Mont Pinçon , driving a six-mile-wide wedge between the German 7th Army and the 5th Panzer Army .

Despite some defeats and failures, Operation Bluecoat, which ended on August 7th, achieved its main objective, namely to keep German troops out of the US sector. The German troops had also been thrown back further inland.

The German counterattack - Operation Liège (August 6th to 8th)

Late in the evening of August 6, 1944, the Germans began a counterattack with the 7th Army, led by Field Marshal Günther von Kluge - the Liège company - in order to repel the Allies.

The German plan provided for 7th Army to break through the Allied line in the southern area of the Cotentin Peninsula and to cut off and rub off American units. Hitler's instructions to do so reached Commander-in-Chief West Kluge on August 2nd.

After initial successes against the American units, especially the 6th US Armored Division, the attack came to a halt due to strong Allied air strikes. Increased Allied resistance forced von Kluge to suspend the attack around midnight on August 8th.

Operation Totalize (August 7-10)

Operation Totalize was carried out on August 7, 1944 by British, Canadian and Polish units. The aim was to break out of the Normandy bridgehead along the Caen – Falaise road.

Because of the withdrawal of the tank units for the Liege company, the Germans had several infantry units take over the front at Caen. The main burden of defense against the further Allied advance lay on the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitler Youth. Field Marshal Montgomery deployed the Canadian II Corps, the 51st (Highland) Division and the Polish 1st Armored Division to support the advance towards Falaise .

The plan was for a night attack without prior artillery fire. Bomber squadrons should attack the flanks first. At the time when the Allied units crossed the starting line, the artillery should fire. After that, two Allied infantry divisions were to attack in the night of August 7th to 8th. Shortly after noon on August 8, USAAF heavy bombers were to attack the German defense positions, whereupon two tank divisions were to break through in the course of the second phase.

1019 Allied aircraft bombed five strong German defensive positions in the night of August 7th to 8th, which were in the path of the Allied units. The bomber squadrons hit the German positions and the streets around them largely precisely. However, as a result of signal errors, around 200 British bombers accidentally dropped their bomb load on parts of the 1st Polish Armored Division north of Caen . The division lost 55 vehicles as a result of the misguided attack, and 497 were killed and wounded. Ten bombers, all Avro Lancaster , were damaged, seven by German fighters , two by FlaK, and one for an unknown reason.

Ian Hamington, commander of a company of mine clearance tanks, reported that the tank crews had almost no field of vision when advancing at night and sometimes could not even see the taillights of the front tanks because it was so dark and there was so much smoke and dust Difficulty seeing. According to him, there was also confusion from the Allied radio communications. Despite these difficulties, the first phase went well for the Allies and was carried out quickly. The second went less well, however, because the Allies were only able to record terrain gains of two kilometers.

In Operation Totalize, tactical innovations and changes were used. Night attacks were always more difficult than day attacks, but they had the advantage of surprise. General Guy Simonds achieved that for Operation M7 Priest Kangaroo tanks , which had been converted for special purposes, for example as medical tanks , were successfully used.

Although the Allies could not reach Falaise, they advanced 13 kilometers and inflicted heavy losses on the Germans - 560 dead and 1,600 wounded. The operation was unsuccessful, but the overall situation in Normandy had changed. American forces were only 25 miles from Simonds' beachhead. If the two units in the Falaise – Argentan area could join forces, they would include the German 7th Army. Simonds then started Operation Tractable to get closer to Falaise. On August 9, the German tank commander Michael Wittmann fell in the course of the fighting during Operation Totalize between Caen and Falaise.

Operation Tractable (August 14th to 15th)

The plan for Operation Tractable was the same as for Operation Totalize. It again envisaged heavy bombardment and a two-phase attack. The operation began on August 14th.

805 aircraft attacked seven German troop positions in support of Canada's 3rd Infantry Division advance on Falaise on August 14, killing two Allied aircraft. A detailed plan was worked out that included the use of luminous markers. Most of the bombing was accurate and effective, but some planes also bombed terrain where parts of Canada's 12th Field Regiment were staying. About 70 bombers fired the wrong area for 70 minutes. The Canadians suffered only minor losses as a result: 13 soldiers were killed, 53 wounded and many vehicles and artillery destroyed. This incident was not the first during the Battle of Normandy, when Allied aircraft formations attacked their own troops. A day later, the Canadian artillery regiment was attacked again by the machine guns of Spitfires of the Royal Air Force and Mustangs of the USAAF .

On the first day, the Allies advanced 8 km, crossing the Laison River, which proved to be a harder obstacle for the tanks to overcome than the Allies had anticipated.

At the end of the second day, August 15, 1944, a large part of the target area was still in German hands.

The Falaise Cauldron (August 16-20)

The attack of the German 5th Panzer Army in a westerly direction, ordered by Hitler, gave the Allies the chance to enclose the Germans between Falaise and Argentan in the so-called Falaise pocket.

On August 8, Patton's 5th US Armored Division reached Le Mans , where it merged with the French 2nd Armored Division under Jacques-Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque . US General Omar Bradley spoke to Bernard Montgomery on the same day and explained his plan to enclose the German army west of the Seine . To do this, Patton's two tank divisions had to turn north from Le Mans in order to merge with Montgomery's divisions, which turned from Caen in a south-westerly direction.

Bradley ordered Patton's XV. Stop Corps north of Argentan. This created a 25 km wide gap through which the German troops tried to escape. Parts of the 12th SS Panzer Division and the Canadian 1st Army then fought hard battles that dragged on for several days. Between August 18 and 21, the basin shrank to form an eight-kilometer-wide street that was shot at by up to 80,000 shells a day and subjected to many air raids. On September 1st the fight was over with the withdrawal of the last German soldiers.

Falaise is to be seen as a victory for the Allies, since the German units lost around 50,000 soldiers (including prisoners of war) and almost all of their heavy weapons between August 7 and 21; However, between 20,000 and 30,000 German soldiers were able to escape from the cauldron, which Antony Beevor attributes to Montgomery's lack of tactical skills.

War crimes

War crimes against German prisoners of war

Kurt Meyer reports on the treatment of German prisoners of war by Canadian troops as follows :

“On June 7th, I was given a notepad from a Canadian captain. In addition to handwritten orders, the notes instructed: 'no prisoners were to be taken'. Some Canadian prisoners were asked [then] if the instructions were true [...] and they said that if the prisoners were obstructing progress, they were ordered not to capture them. "

Meyer is said to have ordered: “What should we do with these prisoners? They just eat our rations. No more prisoners will be taken in the future. "

The Canadian company commander and Major Jacques D. Dextraze said, confirming Meyer's accusations, so to speak :

“We passed the river - the bridge had been blown up. […] We took 85 prisoners of war. I picked an officer and said, 'bring them back to the PW cage.' He went back and ordered them to run to the bridge [...]. These men had run a few miles. They arrived at the bridge exhausted [but the officer said:] No no, you don't take the bridge, you swim. Now the men fell into the water. Most drowned. [...] Then they were taken out of the water by the pioneers who repaired the bridge. I felt very bad seeing them all piled up next to the bridge. [...]. "

War crimes against Canadian prisoners of war

More than 156 Canadian prisoners were reportedly killed near Caen by the 12th SS Panzer Division in the days and weeks after D-Day.

20 Canadians were executed in the massacre in the Abbaye d'Ardenne , near Villons-les-Buissons, northeast of Caen. The commander of the 25th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment of the 12th SS Panzer Division, Kurt Meyer, had moved into his headquarters in the medieval abbey of Abbaye d'Ardenne and, with a high degree of probability, had commissioned the executions.

On June 7, Canadian troops fought near Authie , after which many were held captive at the abbey. Ten were then selected and executed in front of the abbey. The rest were taken to Bretteville-sur-Odon . On the evening of the same day, eleven prisoners were taken into the garden of a country palace and shot.

On the evening of June 8th, seven other prisoners of war who had fought at Authie and Buron were brought to the abbey, questioned and then shot one after the other. The seven Canadians shook hands again before the execution, were then taken into the garden and executed with machine pistol shots in the back of the head. After ten minutes all seven were dead. Polish private Jan Jesionek, who served in the 12th SS Panzer Division, later reported on the events. The last bodies were not found until autumn 1945.

The Abbaye d'Ardenne was conquered by the Regina Rifles at midnight on July 8, 1944.

Kurt Meyer was tried because of the executions in December 1945. However, he denied having known about it. He was sentenced to death anyway, which was later commuted to life imprisonment. He was released from prison on September 7, 1954.

In memory of the Canadian soldiers, a small chapel was set up near the abbey. The chapel consists of a wooden cross above which there is a niche in which a statue of the Virgin Mary was placed. A Canadian steel helmet is attached to the cross. Every year flowers from the children of Authie are deposited at the chapel. In 1984 a bronze plaque was placed at the abbey, on which it reads:

- "On the night of June 7/8, 1944, 18 Canadian soldiers were murdered in this garden while being held here as prisoners of war. Two more prisoners died here or nearby on June 17. They are dead but not forgotten. "

- (German: "On the night of June 7th to 8th, 1944, 18 Canadian prisoners of war were murdered in this garden. Two other prisoners died there or nearby on June 17th. They are dead but not forgotten." )

Aftermath and commemoration

Through Operation Overlord and the battles in Normandy, the Allies managed to gain a foothold and create a solid base in France for the liberation of Europe . On August 25, the Allies ended the Battle of Paris with the capture of the French capital.

Caen and the surrounding villages and towns were largely destroyed. The abbey churches in Caen and the University of Caen , founded in 1432, were also destroyed. The buildings were rebuilt after the war and some were expanded. Because of this, the current symbol of the University of Caen is the phoenix . Around 35,000 residents of Caen were left homeless after the heavy fighting.

The reconstruction of the destroyed Caen officially lasted from 1948 to 1962. On June 6, 2004, Gerhard Schröder, a German Chancellor, was invited to the anniversary celebration of the invasion for the first time.

To commemorate the Battle of Caen and Operation Overlord, many memorials were erected, for example on the road to the Odon Bridge, at Tourmauville a memorial for the 15th Scottish Division or on Hill 112 a monument for the 53rd Welsh Division and one for the 43rd Wessex Division. Furthermore, a new forest was planted near the hill 112, which today serves as a memorial park.

The Mémorial de Caen is a central reminder of the landings in Normandy, the Battle of Caen and the Second World War . It was built on the initiative of the city of Caen over the former command bunker of General Wilhelm Richter , commander of the 716th Infantry Division . On June 6, 1988, it was inaugurated by the then French President François Mitterrand and by twelve ambassadors from the states involved in the struggle in Normandy. The museum is pacifist and borders on the Parc international pour la Liberation de l'Europe , a garden that commemorates the Allied participants in the invasion.

The Allied fallen are buried in Brouay War Cemetery , Banneville-la-Campagne War Cemetery (2,170 graves) and Bretteville-sur-Laize Canadian War Cemetery (2,957 graves).

reception

Movies

- The documentary feature film D-Day 6/6/44 - Decision in Normandy by the British television broadcaster BBC documents the events as they advance towards Caen. Producer: Tim Bradley ; Directed by Richard Dale , Kim Bour , Pamela Gordon , Sally Weale . ( FSK : 16)

- The American black and white documentary "Crusade in Europe" from 1949, which is based on Eisenhower's book, documents Operation Overlord and the Battle of Caen. (FSK: oA)

- The Norman Summer : Canadian documentary from 1962 about the battles for Caen or Normandy. (FSK: oA)

- In the Canadian television film In Desperate Battle: Normandy 1944 from 1992, the battle for Caen is re-enacted.

- Road to Ortona , Turn of the Tide and V Was for Victory and Crisis on the Hill (all 1962): Canadian documentaries on the events.

Games

- Company of Heroes Opposing Fronts : In this real-time strategy game, a campaign is about the battles for Caen. (USK: 16)

- Call of Duty 2 : Computer game by the US game developer Infinity Ward , which was published by Activision on November 3, 2005, in which the British Sergeant John Davis reenacts the attack on Caen. ( USK : 18)

- D-Day : In this real-time tactical computer game, the player can re-enact some of the battle for Caen operations. There is also information and levels etc. on other events around D-Day and the subsequent actions, i.e. the breakout from Normandy. (USK: 16)

- Hidden & Dangerous 2 : You play a British SAS soldier who is supposed to free a town near Caen from the Germans. (USK: 16)

- Day of Defeat : Themultiplayer game basedon the well-known Half-Life offers a world that is based on Caen in its card assortment, which consists of theaters of war from the Second World War. (USK: 16)

literature

- Stephen Badsey: Normandy 1944 - Allied Landings and Breakout . 2nd Edition. Osprey Publishing, London 1991, ISBN 0-85045-921-4 .

- Antony Beevor : D-Day - The Battle of Normandy . Pantheon Verlag, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-570-55146-2 , Chapter 12 - Failure at Caen; 17 - Caen and the Calvary; 19 - “Operation Goodwood” (British English: D-Day - The Battle for Normandy . Translated by Helmut Ettinger).

- Ian Daglish: Goodwood: The British Offensive in Normandy, July 1944 . Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg 2009, ISBN 978-0-8117-3538-4 .

- Ken Ford: Caen 1944 - Montgomery's Break-out Attempt . Osprey Publishing, London 2004, ISBN 1-84176-625-9 .

- Henry Maule: Caen - The Brutal Battle and the Break-out from Normandy After the D-Day Landings . 3. Edition. David & Charles, Newton Abbot 1988, ISBN 0-7153-7283-1 .

- Simon Threw, Stephen Badsey: Battle for Caen (= Battle Zone Normandy . Volume 11 ). Sutton Publishing, Stroud 2004, ISBN 0-7509-3010-1 .

- Horst Mayer: The struggle for Caen . In: Soldier Fates . Pabel-Moewig, Rastatt 2002, ISBN 3-8118-5590-5 .

Web links

- Mémorial de Caen, Normandy Museum. Arromanches 360 tourisme. Histoire débarquement. Le mémorial de Caen, accessed on November 19, 2012 (French, English).

- Info (english)

- Operation Bluecoat at BBC (English)

- Information about the massacre (English)

- Summary of the Battle for Caen (English)

- Information on Operation Charnwood ( Memento dated February 4, 2009 on the Internet Archive )

- Information on the Battle of Hill 112 ( Memento from July 12, 2004 in the Internet Archive )

- Information at valourandhorror.com (English)

- Maps (english)

- Diary of the Royal Air Force (English)

- Information ( Memento from September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ornebridgehead.org (English)

- junobeach.org (English)

- Information on the battlefield (English)

- Operation Charnwood (PDF)

Notes and individual references

- ↑ a b Explanation of symbols see military symbols

- ↑ Tony Hall (Ed.): Operation "Overlord". The landing of the Allies in Normandy in 1944. Motorbuch, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-613-02407-1 , p. 160.

- ↑ Percy E. Schramm: War Diary of the High Command of the Wehrmacht. Volume 7 (= TBd 4.1). January 1, 1944 - May 22, 1945. Bernard & Graefe, Bonn 1961, ISBN 3-7637-5933-6 , p. 325.

- ↑ a b c d British Ministry of Defense: Drive on Caen ( Memento of January 26, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF).

- ↑ Yves Lecouturier: Discovery Paths - The Beaches of the Allied Landing. Éditions Ouest-France Entreprises 35. Morstadt, Kehl / Rhein 2003, ISBN 3-88571-287-3 , p. 102.

- ^ Piekałkiewicz, Janusz: The Invasion. France 1944 . FA Herbig Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH, Munich 1994, p. 204.

- ↑ Tony Hall (Ed.): Operation "Overlord". The landing of the Allies in Normandy in 1944. Motorbuch, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-613-02407-1 , p. 187.

- ^ Antony Beevor: D-Day. The battle for Normandy. Munich 2010, p. 507 f.

- ↑ a b POWs ( Memento from January 16, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) on valourandhorror.com.

- ^ Report by a Polish corporal from the 12th SS Panzer Division , waramps approx.