Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross

The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross (also known as the Knight's Cross to the Iron Cross ) is a step of the Iron Cross , which was newly donated by Adolf Hitler on September 1, 1939, on the occasion of the attack on Poland . The Knight's Cross was awarded over 7,000 times, and additional levels were introduced in the course of the war. During the time of National Socialism , the owners of the Knight's Cross, so-called “Knight's Cross bearers”, were considered “ heroes ” and enjoyed the highest degree of reputation and popularity generated by the Nazi propaganda , often they had their own autograph cards. They visited schools and gave lectures at events organized by the Hitler Youth , and their public appearances were always accompanied by major honors. In addition to flying races and submarine drivers, the propaganda primarily served adolescents with “knight's cross bearers” as heroic role models.

The image of the "Knight Cross Bearers" was determined until the 1990s by the relevant publications from the environment of the Order Community of Knight Cross Bearers (OdR), which also had good contacts to the armed forces and politics.

General

The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross is probably the most popular National Socialist war medal. Its owners, the so-called "Knight's Cross bearers", enjoyed a high reputation inside and outside the Wehrmacht , which is primarily due to Nazi propaganda. Young people were presented with the knight's cross bearers as role models and leading figures. During the war, numerous lists of knight's cross bearers and biographies, postcards and other devotional items appeared . Knight cross bearers were adored as stars , autograph cards and knight cross postcards were coveted collector's items.

The aim of this hero cult was the spiritual mobilization of the nation, especially the male youth. The trivial writer Ursula Colell described these expectations as follows: “The youth of the Third Reich sees you [note: the“ heroes ”[…]] as their role model and tries to do justice to your life and death, later as whole German men to defend the fatherland. ”The Wehrmacht High Command sent knight's cross bearers to schools and HJ events so that they could report on their experiences at the front, for example Wolfgang Lüth gave a lecture on April 10, 1941 in Herford, which ended with the words:“ Get on the enemy - until England is on the ground, that is the slogan for us submarine drivers too. ”On the one hand, they cultivated a spirit of war on the“ home front ”, and on the other hand they were supposed to be a role model for those in the last days of the lost war be recruited youth. The historian Reinhart Koselleck attested to his generation that they “certainly had a certain ambition to perhaps prove themselves as a hero”. In the last year of the war, schoolchildren drove “to the front with the idea that I will now die a hero's death”; even in the last days of the war people still trusted in the aura of the “heroes”.

However, the heroic image of the knight's cross bearers also had disadvantages. Lower ranks of the Knight's Cross had an above-average mortality rate, as the expectations attached to them meant that they were obliged to be particularly brave and daring . The Stalingrad veteran Günter K. Koschorrek described the fate of his comrade Gustav, who was promoted to non-commissioned officer because of his knight's cross and from then on was assigned to every suicide mission until he fell a few months later:

“Simple compatriots have a particularly difficult time with this award. Everyone does not see them as the random hero, but as the dashing daredevil who is fearless in every combat situation and who rushes forward courageously. Poor Gustav! If they passed you around as a role model for a heroic compatriot, you will be sent back to the front as tough as a rock. But your chances of survival will be far less this time than before. Because all your superiors will use you as a particularly bold hero wherever it is particularly tricky and where they expect the greatest benefit from a hero. This is probably the reason why only a few simple soldiers survived their knight's cross. "

In the memorial literature it is often pointed out that risky ventures to win medals cost many soldiers their lives. An officer who wanted to decorate his bare neck with a knight's cross at the expense of the troops he led suffered from a "sore throat" in soldiers' jargon .

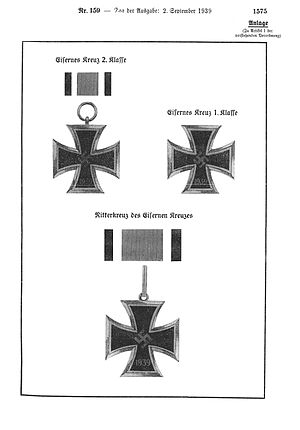

Appearance and wearing style

The design of the knight's cross , like the previous iron crosses of other foundation years (see Iron Cross ), was based on the Balkenkreuz - a black paw cross with typical, widening bar ends on a white coat, as the German knights wore since the 14th century. The original design came from Karl Friedrich Schinkel . The appearance of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross corresponds to the Iron Cross 1st Class (1939). The width was around 48–49 mm and the height with the small eyelet 54–55 mm. It had a weight (without jump ring) of about 27.8-34.5 grams, with weights and dimensions varying due to the large number of manufacturers. On its front, a swastika standing on top was embossed in the middle on a black background. The foundation year is on the lower bar 1939. The back of the cross is black and empty. Only on the lower bar is the year 1813embossed, which symbolizes the first year of the foundation of the Iron Cross in 1813. The black (mostly magnetic) iron core is surrounded by a galvanized silver frame. A gold border was dispensed with because Hitler had reservations about a gold-framed cross that would have meant a departure from Prussian tradition. Although large crosses with a gold rim were known from previous years (manufacturer Juncker Berlin), they were replaced by silver ones again.

The Knight's Cross is often confused with the Iron Cross 2nd class because of its similarity. In addition to the size, you can easily differentiate between the two medals. In the Knight's Cross, an oval jump ring was attached to the small, round eyelet, while in the EK II, a large round ring is attached to the small, differently arranged eyelet.

The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross was worn as an order of collar on a black, white and red ribbon and, if already awarded, over the Pour le Mérite and over the other medals awarded.

Bearers of the Knight's Cross always had to be greeted first, regardless of their rank - contrary to the other rule, "lower rank greets higher rank first".

Classification of the knight's cross

The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross was until June 1940 the second highest military award of the “ Third Reich ”. Above it was only the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross , which was only awarded to Hermann Göring on July 19, 1940 during the Second World War , but was revoked from him shortly before the end of the war in April 1945. The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross was ranked between the Iron Cross 1st Class and the Grand Cross. The levels of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross were ascending from left to right:

| The steps of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross (from September 1, 1939) | Oak leaves for the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross (from June 3, 1940) | Oak leaves with swords for the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross (from September 28, 1941) | Oak leaves with swords and diamonds for the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross (from September 28, 1941) | Golden oak leaves with swords and diamonds for the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross (from December 29, 1944) | ||

Award certificates

All award certificates and award books have in common that the name and the rank of the borrower current at the time of the award are mentioned on the inside. The award certificates and award books are characterized as follows:

- Knight's Cross: red cover with gold-embossed imperial eagle on the outside

- Knight's cross with oak leaves: white cover with a gold-embossed imperial eagle on the outside

- Knight's cross with oak leaves and swords: white cover with a wide, golden decorative strip all around and an imperial eagle embossed with gold on the outside

- Knight's cross with oak leaves, swords and diamonds: dark blue or black cover with a wide, surrounding golden decorative strip and a gold-embossed imperial eagle on the outside

- Knight's Cross with golden oak leaves, swords and diamonds: like previous level, but with golden instead of silver (or iron-colored) oak leaves.

Authority to award

September 1, 1939 to April 20, 1945

Clerk / Berlin (preliminary) → Chief Army Personnel Office / Berlin (preliminary) → OKW Adjutantur / Berlin (present) → Hitler (decisive)

(From April 21 to 24, 1945, the Army Personnel Office branch was split off due to the war and relocated to Marktschellenberg .)

April 25, 1945 to April 30, 1945 (Hitler's death)

Clerk / Marktschellenberg (preliminary) → Deputy Chief Army Personnel Office / Marktschellenberg (preliminary) → Chief HPA / Berlin (preliminary) → OKW Adjutantur / Berlin (present) → Hitler (decisive)

From April 30, 1945

After Hitler's death on April 30, 1945, the authority to award the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross became confusing. General Ernst Maisel (1896–1978), Deputy Head of the Army Personnel Office, was authorized by the Presidential Chancellery to award knight's crosses with effect from April 28, 1945 . Maisel did this by awarding 33 knight's crosses with legal effect on April 30, 1945. He rejected 29 proposals, 4 were postponed. Then the awards end. The background to this was that after the news of Hitler's death on May 1, 1945, Maisel no longer saw the "possibility of a later signature [by Hitler]". In theory, the ceremony went right for the Knights Cross of May 1, 1945, that of Hitler " testamentary " named new head of state Karl Doenitz over.

From May 3, 1945

With a telex dated May 3, 1945, an extended “transfer authorization to award the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross” was sent to the relevant commander-in-chief of the units still fighting. Accordingly, the following decision-making chains were possible at this point in time:

- North area

- (Clerk) → Chief Army Personnel Office / Flensburg → Chief OKW / Flensburg → Dönitz / Flensburg

- Commander in Chief North: Ernst Busch

- Commander-in-Chief of Army Group Courland : Carl Hilpert

- Commander in Chief East Prussia: Dietrich von Saucken

- Commander in Chief Norway: Franz Böhme

- Commander in Chief Denmark: Georg Lindemann

- (Commander in Chief Army Group Vistula ): Kurt von Tippelskirch (already deleted from the distribution list on May 3, 1945)

- South room

- Commander in Chief Army Group G : Albert Kesselring

- Commander in Chief Army Group E : Alexander Löhr

- Commander in Chief Ostmark: Lothar Rendulic

- Commander in Chief Army Group Center : Ferdinand Schörner

- Commander in Chief Army Group C : Heinrich von Vietinghoff (deleted from distribution list on May 2, 1945)

From May 7, 1945

- North area

- (Clerk) → Chief Army Personnel Office / Flensburg → Chief OKW / Flensburg → Dönitz / Flensburg

- Commander-in-Chief of Army Group Courland: Carl Hilpert

- Commander in Chief East Prussia: Dietrich von Saucken

- South room

- Commander in Chief Army Group G: Albert Kesselring (theoretically, since this Army Group surrendered on May 5th)

- Commander in Chief Army Group E: Alexander Löhr

- Commander in Chief Army Group Center: Ferdinand Schörner

- Commander in Chief Ostmark: Lothar Rendulic

From May 9, 1945

With the unconditional surrender on May 8, 1945 , all sovereign functions within the Wehrmacht ended, therefore all awards and promotions after this date (i.e. administrative acts) are legally ineffective.

The law on titles, medals and decorations of July 26, 1957 consequently deals in the section Special provisions for previously awarded decorations and decorations only those awards that were awarded up to and including May 8, 1945.

Award Regulations

The person to be loaned had to have both classes of the Iron Cross before being awarded the RK. An EK from the First World War that had already been awarded was not taken into account. In accordance with the " National Socialist attitude of the new Wehrmacht ", all levels were awarded regardless of rank. In some cases, the Knight's Cross was awarded at the same time as EK II and I. Each award was not only preceded by the deed or the deeds, but also by an award proposal (VV). Proposals could be made from company level, in the case of artillery from battery level and in the case of the Air Force from staff level. Commanders, however, were not allowed to propose themselves, but had to be suggested by superiors. Soldiers who were already holders of a knight's cross and were proposed again because of another act did not receive additional knight's crosses, but instead the higher level, for example only the "oak leaves to the knight's cross", "swords to the oak leaves" etc. From the The award was numbered level “with oak leaves”. For example, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel was the 6th holder of the diamonds. The classes "with diamonds" and "with golden Eichenlaub" the Beliehenen were presented in duplicate - so-called A- and B-pieces , wherein the A-class "Real-diamonds" and the B version (the supporting portion ) with simili stones was occupied. The aforementioned A and B pieces differ not only in the materials used, but also in shape and size (see detailed images above, which all show A pieces. Corresponding B pieces can be seen in the photo gallery). In the ordinance on the renewal of the Iron Cross of September 1, 1939 ( RGBl . 1939 IS 1573) it said:

- Article 1

The Iron Cross is awarded in the following grading and order:- Iron Cross 2nd Class,

- Iron Cross 1st Class,

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross,

- Grand Cross of the Iron Cross.

- Article 2

The Iron Cross is awarded exclusively for special bravery in front of the enemy and for outstanding services in the command of the troops. The award of a higher class requires possession of the previous class. - Article 3

I reserve the right to award the Grand Cross [note: Adolf Hitler] for outstanding deeds that have a decisive influence on the course of the fighting.

Article 1 received several expansions in the form of an ordinance amending the ordinance on the renewal of the Iron Cross , in which further classes of the Knight's Cross were introduced.

- June 3, 1940:

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with oak leaves

- September 28, 1941:

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with oak leaves and swords

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with oak leaves, swords and diamonds

- December 29, 1944:

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with golden oak leaves, swords and diamonds . The award should only be given twelve times to “highly proven lone fighters”. In fact, it was only awarded once - to the attack pilot Hans-Ulrich Rudel .

Award practice

Especially in the early years of World War II, but later only in the higher classes, the award was given personally by Adolf Hitler.

Together with the handover of the medal, the recipient of the award also received an award certificate in book form. In the later years of the war the award certificates were no longer issued, but held back at the Fuehrer's headquarters. They should only be distributed after the "final victory". The award was also linked to the state plan to exempt the porters from all taxes after the war. Since the war lasted longer than expected, the Knight's Cross was gradually expanded by three levels. At the end of the war, a fifth tier was added, but it was only awarded once.

Award practice of the Kriegsmarine

When the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross was awarded, especially to the submarine commanders, the following provision applied:

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross after 100,000 GRT sunk ship space

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with oak leaves after 200,000 GRT sunk ship space

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with oak leaves and swords after 300,000 GRT sunk ship space

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with oak leaves, swords and diamonds after 400,000 GRT sunk ship's space

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with golden oak leaves, swords and diamonds after 500,000 GRT sunk ship's space (not reached)

In order to be able to present more successful knight cross bearers to the public, these criteria were "constantly undermined" in the course of the war. In particular towards the end of the war there were "increasingly mysterious decorations of the order". Checks of the figures of the U-boat special reports from the Second World War showed that of the 122 U-boat commanders who were awarded the Knight's Cross, only 31 had sunk over 100,000 GRT of shipping space. (“There were even officers decorated with the Knight's Cross without sinking results”.) It was also in keeping with the naval practice of the time that the commanders extrapolated their sinking figures using estimates.

The reliability of the reports of success had already been questioned by the naval command during the war. According to its own evaluations, the 3rd (news evaluation ) department of the naval war command (Foreign Marines) considered the "absurdly high" reports about sunk tonnage to be "grotesquely exaggerated". Karl Dönitz admitted in the post-war period that the reports of sinking were above the real numbers, but in his opinion "only a little". Even after the war, the tonnage figures on which the awards were based were critically questioned.

Award practice among the fighter pilots of the Luftwaffe

The knight's cross was initially awarded to fighter pilots for shooting down at least 20 enemy aircraft, the "oak leaves" level for 40 kills. However, it was in accordance with the air force practice of the time that the fighter pilots manipulated their shooting figures. That was known in the Wehrmacht leadership. The head of the Wehrmacht Propaganda Department (WPr) of the OKW , which prepared the Wehrmacht report, complained that the Luftwaffe was “using numbers to kill enemy planes” . The numbers were also questioned by Adolf Hitler and by the army . The historian Karl-Heinz Frieser , on the other hand, regards the criteria for confirming a kill by the Luftwaffe as strict, the number of machines reported as lost by the Allies is often far higher than the number of machines reported by the Luftwaffe.

Award practice towards the end of the war

At the beginning of the war, the Knight's Cross was mainly awarded for management tasks, but the requirements changed during the course of the war, which resulted in an increase in the number of awards and more awards to lower ranks. Especially towards the end of the war, knight's crosses were increasingly awarded to strengthen the soldiers' motivation and perseverance. In Hitler's mind the German soldier had to win or die. Captivity was not an option. Accordingly, he decreed on November 27, 1944, "... that war awards may no longer be awarded to missing, prisoner-of-war and interned members of the Wehrmacht" . The fact that they were arrested or interned through no fault of their own does not matter. However, awards after death did occur. Until the beginning of 1945, Hitler generally did not reject any award proposals (VV) for the Knight's Cross. Only in the last five months of the war did his attitude change. From December 1944 to the end of April 1945, a total of 30 awards were rejected (for the army), which corresponded to a quota of 3%.

Shortly before the end of the war, on March 7, 1945, Hitler ordered the Commander-in-Chief of the Replacement Army, Staff IIa, No. 5773/45 (full wording): “Today the Führer ordered that every soldier with a bazooka or makeshift Melee weapons destroyed 6 enemy tanks, received the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross. Kills with a stove pipe ( rocket armored rifle 54 ) are subject to a special rating. This provision must be made known to all soldiers as quickly as possible. It has no retroactive effect. The knight's cross proposals are to be sent by telex from the submitting office directly to the head of the Army Personnel Office (HPA) at the Führer Headquarters with the shortest possible justification, specifying the means of destruction and listing the required personal details. At the same time, a report must be made to the superior departments. "

With the beginning of April 1945, the conditions for awarding the Knight's Cross became increasingly confusing. Many knight's crosses were pronounced arbitrarily by commanders of individual battalions, without these persons having been authorized or the proper application not even being submitted to the presidential chancellery. These awards are all invalid. All awards after the capitulation on May 8, 1945 are also ineffective , since any sovereign act (including promotions and awards) was deprived of its legal basis. The majority of the knight's cross awards known today can be proven beyond doubt.

Revoked awards

Awards could not only be awarded, but also withdrawn under certain circumstances.

July 20, 1944

In connection with the assassination attempt on July 20, 1944 , several knight's cross winners were denied military status, which resulted in the loss of all medals and decorations . It was in line with Hitler's express wish not to have the officers involved convicted by the military justice system responsible for military personnel, but to bring them to trial before Freisler 's People's Court. Since the People's Court was not responsible for members of the military, Hitler created a “new military body”, the so-called Ehrenhof , whose sole task was to check “who is somehow involved in the attack and should be expelled from the army” and “who will initially be dismissed as suspicious. ”The officers proposed by the Court of Honor were personally expelled or dismissed from the army on August 4, 1944 by the Commander-in-Chief of the Army, Adolf Hitler, and could thus, since civilians, be transferred to the People's Court, where they were were sentenced to death. At the same time they were deprived of their military worth, which was mandatory under the law of the time. This was a so-called “honor penalty” according to Section 30 of the Military Criminal Code and resulted in “the loss of the position and the associated awards, the permanent loss of medals and decorations” and “the inability to re-join the armed forces”. The following were excluded from the army and sentenced by the People's Court:

- Friedrich Fromm

- Otto Herfurth

- Roland von Hößlin

- Friedrich Gustav Jaeger

- Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel

- Karl Freiherr von Thüngen

- Erwin von Witzleben

- Fritz Lindemann

- Friedrich Olbricht

- Erich Hoepner

- Gustav Heisterman von Ziehlberg

Other disallowed awards

- Hans Graf von Sponeck

- Walther von Seydlitz-Kurzbach (with a judgment of February 18, 1956 by the Verden Regional Court, the withdrawal was lifted again)

- Edgar Feuchtinger

- Hermann Fegelein

Award numbers

| gradation | number | carrier |

|---|---|---|

| Knight's cross | 7,313 | |

| Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves | 863 | |

| Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords | 148 | |

| Knight's cross with oak leaves, swords and diamonds | 27 | |

| Knight's cross with golden oak leaves, swords and diamonds | 1 | Hans-Ulrich Rudel (on December 29, 1944) |

The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross has been awarded 43 times to members of foreign armed forces: 18 Romanians, nine Italians, eight Hungarians, two Slovaks, two Finns, two Spaniards and two Japanese.

The knight's cross in parlance

In the soldier's jargon at the time , the award was also referred to as a "sheet metal tie" or "neck iron". Soldiers who aspired to the Knight's Cross with great ambition were considered "sore throat" or had a "sore throat" in the troops.

In today's soldier language, a "Knight's Cross Order" is often referred to as an order or command that poses a particular challenge to the soldier. This is not always meant very seriously. Typical "Knight's Cross Orders" include, for example, taking the commander's daughter to the location ball as an officer candidate or having lunch with the inspecting general as a basic military service. Günter Grass uses the Knight's Cross in his novella Katz und Maus as an example of how people try to cover up their own weaknesses or physical ailments (here: an oversized Adam's apple) with medals.

Others

According to the law on titles, medals and decorations of July 26, 1957, wearing the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross (with all its levels) in the Federal Republic of Germany is only permitted without National Socialist emblems. The only known Knight's Cross manufacturer in the Federal Republic is the Steinhauer & Lück company in Lüdenscheid . The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with all its levels as well as all other orders and decorations from the period from 1933 to 1945 were neither allowed to be worn nor produced in the German Democratic Republic . This regulation also applied to knight cross bearers who served in the ranks of the NVA .

The Order of the Knight's Cross Bearers (OdR)

The OdR is considered an elite organization among the traditional associations, its members enjoyed a high reputation among conservative politicians and members of the Bundeswehr. 674 Wehrmacht Knight's Cross bearers served in the Bundeswehr, 117 of whom rose to general ranks. Representatives of the Bundeswehr were often represented at federal meetings of the OdR. Characteristic for the OdR is the uncritical glorification of military virtues as well as the denial or relativization of German war guilt. The OdR publishes the magazine "Das Ritterkreuz" , of which Kurt-Gerhard Klietmann was the editor for many years . On March 4, 1999, the Federal Minister of Defense, Rudolf Scharping , prohibited all contacts between the Bundeswehr and the “religious order”, which was classified as revanchist , because the community was close to right-wing radicalism . The religious order is led by people "who are very close to right-wing radicalism, some directly in it," said Scharping.

Independent research on the award of knight crosses has only existed for a few years. Before that, the "Knight's Cross bearers" wrote their story themselves to a large extent. Who is or was a "Knight's Cross bearer" was determined by the so-called Order Commission of the Order Community of Knight Cross Bearers, often based on the association's policy or personal preferences of the respective chairperson. In the publications from their environment, a number of awards are described for which either no evidence exists, which is legally ineffective or so impossible to have taken place.

In 1952, the former fighter pilot and bearer of oak leaves, Adolf Dickfeld, founded the "Association of Knight Cross Bearers" (GdR), in which many of the surviving Knight Cross bearers organized themselves. The "community" was dissolved in 1955 and on November 24 of the same year under Colonel General a. D. Alfred Keller newly founded in Wahn am Rhein in order to dedicate himself to "the reputation and honor of German soldiers, in whose unchangeable virtues the sense of duty, willingness to make sacrifices and camaraderie are preserved". In 1958, Gerhard von Seemen took over the management of the association, which in 1960 was renamed “Ordensgemeinschaft der Ritterkreuzträger e. V. “(OdR). The GdR had tried to achieve an honorary salary for knight cross bearers.

It was also Gerhard von Seemen who, with his book Die Ritterkreuzträger 1939–1945, laid the foundation for all known publications about knight cross bearers in 1955 . Previously, he had compiled a list of Knight's Cross bearers through calls in newspapers, questioning other traditional associations, evaluating daily newspapers, etc. He also used printed sources from the Third Reich, including the Völkischer Beobachter . Access to the documents of the former German armed forces was not yet possible at this time because they were still in the custody of the victorious powers. After the captured documents were returned to the Federal Republic, v. Seemen took this off, revised his manuscript and published a second edition in 1976.

Since the founding of the GdR there have been problems with missing evidence, especially for awards at the end of the war. At the beginning of the 1980s, Walther-Peer Fellgiebel , Walther-Peer Fellgiebel , the long-time 2nd chairman of the OdR and chairman of the association's internal "Order Commission" , began to work on the work of v. To revise Seemen again and to correct errors contained therein. 1986 appeared under the title The Bearers of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross: 1939–1945 a revised new edition, in which over a hundred names were no longer mentioned, but a larger number of unsubstantiated or insufficiently documented awards were added. The supplementary volume published in 1988 contains a further 1160 corrections. Despite its numerous errors and unsubstantiated awards, Die Ritterkreuzträger 1939–1945 was considered a standard work for a long time:

- Setting the tone in answering the question "Who is a Knight's Cross and who is not?" Was always the OdR. The standard work on this and the previous work were written by OdR members and are considered sacred by collectors and interested parties. Anyone named in it is a bearer of the Knight's Cross. From the point of view of current research, von Seemen and Fellgiebel were biased as members of the association and gave association interests priority over historical truth . Personal sympathy or antipathy could also decide whether to be recognized as a “Knight's Cross”.

- If one approached the chairman in a fitting manner, a lot was evidently possible. One of v. Seemen unrecognized SS-Obersturmbannführer a for lack of evidence. D. tried it again at Fellgiebel. He wrote in the summer of 1974: “... I would like to simply submit to your decision as the Chairman of the Order Commission and its members at the Knight's Cross. The fact that I would immediately apply for membership in the religious community in the event of a positive result does not need to be discussed ”. A short time later the OdR had a new member.

Fellgiebel justified his decisions in a letter to the non-fiction author Manfred Dörr : “... we as OdR can say, just like any rabbit club, we recognize them and we don't. “In response to Dörr's accusation that the book was not an official reference work, but only an expanded list of members of the OdR, Fellgiebel replied:“ I - or the OdR - have never claimed that this book is an 'official or official' reference work. It is of course a reference work, but as I said without 'officially u. officially '“The best-known example of the association's policy is the case of the right-wing extremist and former OdR member Otto Riehs . After he is said to have passed on addresses of OdR members to the Stasi and then fell out with the "religious order", his name disappeared in the early 1990s from numerous directories of Knight's Cross bearers.

The "Dönitz Decree"

The so-called “Dönitz Decree” describes an oral instruction that is rumored in the relevant literature and that the former Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz claims to have made. According to her, all recruitment proposals in the personnel offices at the end of the war were approved as a blanket if they met certain conditions. The only indication that such an order could actually have been issued is a letter from the honorary member of the OdR Dönitz to the order community of knight cross bearers dated September 20, 1970.

This letter was first published in 1976 in the second edition by v. Seemens The knight's cross bearers 1939–1945 . In the foreword mentioned by v. Seemen the "Statement of the last Reich President, Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz", and describes it there as the "Dönitz Declaration".

|

The "Dönitz Declaration"

"Shortly before the capitulation came into force, probably on May 7, 1945, I verbally issued the following order: All proposals for the award of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross and its higher ranks received by the High Command of the Wehrmacht / Wehrmacht Command Staff before the capitulation came into force are approved by me, provided that the proposals are duly approved by those authorized to make proposals from the Wehrmacht parts, the army including the Waffen SS and the navy and Luftwaffe up to the level of the Army and Army Group Leader. With friendly greetings Dönitz " |

It is neither clear to whom this statement was made against Dönitz, nor was such an order announced, for example, in the army bulletin. There is no reference or evidence for such an “order”, apart from the aforementioned letter from Dönitz himself. Nevertheless, this oral instruction, often referred to as the “Dönitz Decree”, is used again and again in the relevant literature, if the award cannot be proven, the letter can be found as a copy or copy in the publications, for example by Fellgiebel, v. Seemen and Krätschmer.

The misleading and legally incorrect term “decree” appeared for the first time in 1986 in Fellgiebel's “The Bearers of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross: 1939–1945”.

Even if one assumes that the “order” was actually issued, it raises a number of problems that make awards about the “Dönitz Decree” appear questionable. First there is the area of validity that Dönitz specifies as the "Wehrmacht-Wehrmacht Execution Staff".

The command staffs "A" and "B" were formed from the merged parts of the Wehrmacht command staff and the general staff of the army. The command staff "A" was merged on April 22nd with the entire staff OKW and from then on was the only staff to be called "Wehrmacht / Wehrmacht execution staff". Most of the "B" staff was captured by US troops on May 3, 1945 between Berchtesgaden and Reichenhall; by May 7, the rest of the prisoners were also taken into custody.

"Wehrmacht / Wehrmachts execution staff" therefore exclusively referred to the command authority in Flensburg, which means that all award proposals (VV) received by the Army Personnel Office (HPA) in the southern area would not be affected by the dubious "Dönitz Decree" anyway. Doenitz's order, if it was actually issued, covered at most those proposals that had already passed all departments and personnel offices, were supported by everyone and were ready for signature by the time the surrender came into force on May 8, 1945. In total, only eleven knight's crosses and two oak leaves would have been awarded by the arrangement. Only these would be approved by the supposed “Dönitz Decree”.

More serious than the restricted area of validity is the fact that, in the opinion of a number of experts, such an order would be legally ineffective. In 1988 Manfred Dörr commissioned the Wehrmacht Information Center (WASt) for an expert opinion on the legal validity of awards after May 8, 1945. In it, the WASt comes to the conclusion that a “Dönitz order” has no legal basis because the award was established by an ordinance. An order given orally is at best an order and as such is bound by the law applicable at the time, i.e. the Foundation Ordinance:

- “An order in this form can only be a military order. A military order is subject to applicable legal norms, it cannot change any existing law. [...] Even under the law of the time, the existing ordinance could only have been changed by an equal (ordinance) or higher-ranking (law) legal norm. "

However, the Foundation Ordinance did not provide for a general decision, but for an individual examination. In the opinion of the expert, Dönitz should have either checked or signed each award proposal (VV) individually or issued an amending ordinance. Since this did not happen, even the thirteen awards mentioned above are ineffective.

Fellgiebel, the then managing director of OdR, protested against the report and wrote a letter to WASt on December 22, 1989, in which he questioned the expertise of the expert:

- “... What right does your department have to issue such an opinion without reservation? [...] Is Mr. Gericke really authorized [sic!] For such a historically significant assessment signed “on behalf” d. H. to give away for your office and thereby 'turn things upside down'? "

On January 25, 1990, the then head of WASt, Urs Veit, answered the request:

- "... I would like to say that Mr. Gericke, as head of the naval department of the German Office (WASt), is competent and responsible for issuing such expert opinions."

The “Dönitz Decree” was always applied by the OdR when an award could not be proven (in a number of cases it was even legally rejected!), But the person in question was to be accommodated . An OdR member, for example, who proposed four new cases in 1985, although there was no official evidence of their awards, wrote the chairman of the OdR's “Order Commission”, Walter-Peer Fellgiebel: “Undoubtedly, some gentlemen could fall under the Dönitz Decree 'accommodate “.

Fellgiebel knew exactly what he was doing; based on the "Dönitz Decree" he determined:

- "If documents are available in the OKW / OKH PA or equivalent offices and approved by all offices, but no real award has been made - i.e. the Dönitz decree can be applied - we will list the person in question under 8.5.1945. If no official proposal documents are available, but submission through other evidence is known or similar circumstances, then date 9.5.1945, so that at least we [note. The OdR] can distinguish what is as good as real and which names are at least allowed to be doubted! [...] because on 8.5. or 9.5. there was no longer any real award [...] "

In total, with over 7300 awards recognized by the OdR, an official award certificate is missing in 200 cases.

literature

- Veit Scherzer : Knight's Cross bearer 1939–1945. The holders of the Iron Cross of the Army, Air Force, Navy, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm and armed forces allied with Germany according to the documents of the Federal Archives. 2nd Edition. Scherzers Militaer-Verlag, Ranis / Jena 2007, ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2 .

- Veit Scherzer: Knight's Cross bearer 1939–1945. The holders of the Iron Cross of the Army, Air Force, Navy, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm and armed forces allied with Germany according to the documents of the Federal Archives. Volume: Documents. Scherzers Militaer-Verlag, Ranis / Jena 2006, ISBN 3-938845-09-0 .

- Werner Otto Hütte: The history of the Iron Cross and its significance for the Prussian and German labeling system from 1813 to the present. Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn , 1967, DNB 482182385

- Ralph Winkle: Thanks from the fatherland. A history of symbols of the Iron Cross 1914 to 1936. Klartext, Essen 2007, ISBN 978-3-89861-610-2 .

- Jörg Nimmergut : German medals and decorations until 1945. Volume 4: Württemberg II - German Empire. Zentralstelle für Wissenschaftliche Ordenskunde, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-00-001396-2 , pp. 2108-2131.

From the authors of the OdR:

- Walther-Peer Fellgiebel : The bearers of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross: 1939–1945. Podzun-Pallas, ISBN 3-7909-0284-5 .

- Gerhard von Seemen: The knight's cross bearers, 1939–1945: The knight's cross bearers of all Wehrmacht parts, diamond, sword and oak leaf bearers in the order in which they were awarded. Podzun-Verlag, 1955, ISBN 3-7909-0051-6 .

- Franz Thomas and Günter Wegmann (eds.): The knight's cross bearers of the German Wehrmacht 1939–1945. Biblio-Verlag, multi-volume series.

Web links

- Crime under the oak leaves: the knight's cross bearers. A fine company , critical article of the Holocaust Reference

- Dieter Pohl : Order for Mass Murder , in Die Zeit No. 24, June 5, 2008

- Foundation Ordinance : Ordinance on the renewal of the Iron Cross in the Reich Law Gazette of September 1, 1939

Individual evidence

- ↑ See Veit Scherzer (2005), p. 7 ff.

- ^ Paul Schäfer: Bundeswehr and right-wing extremism . In: Science & Peace. Dossier 28, 2/98, ISSN 0947-3971

- ↑ Rolf Schörken: "Student soldiers" - coinage of a generation. In: Rolf-Dieter Müller, Hans-Erich Volkmann (Hrsg.): The Wehrmacht. Myth and Reality. Oldenbourg, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-486-56383-1 , p. 466.

- ↑ René Schilling: The "Heroes of the Wehrmacht" - Construction and Reception. In: Rolf-Dieter Müller, Hans-Erich Volkmann (Hrsg.): The Wehrmacht. Myth and Reality. Oldenbourg, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-486-56383-1 , p. 570 ff.

- ^ Andreas Jordan: Student soldiers, Gelsenzentrum, portal for the city and contemporary history.

- ↑ Cf. Christian Hartmann: Von Feldherren und Gefritt. On the biographical dimension of the Second World War. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-486-58144-7 , p. 53.

- ^ Gudrun Wilcke: The children's and youth literature of the National Socialism as an instrument of ideological influence: song texts, stories and novels, school books, magazines, stage works. Lang, 2005, ISBN 3-631-54163-5 , p. 43 f.

- ↑ Otto May: Staging of seduction: the postcard as a witness of an authoritarian upbringing in the III. Rich. Brücke-Verlag Kurt Schmersow, Hildesheim 2003, ISBN 3-87105-033-4 , pp. 455-461, cf. P. 71ff. and p. 380 f.

- ↑ Katrin Blum: The Eye of the Third Reich: Hitler's cameraman and photographer Walter Frentz. Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2006, ISBN 3-422-06618-7 , p. 151 f.

- ↑ Sascha Feuchert , Erwin Leibfried, Jörg Riecke : Last days. Wallstein Verlag, 2004, ISBN 3-89244-801-9 .

- ↑ Quoted by René Schilling: The "Heroes of the Wehrmacht" - construction and reception. In: Rolf-Dieter Müller, Hans-Erich Volkmann (Hrsg.): The Wehrmacht. Myth and Reality. Oldenbourg, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-486-56383-1 , p. 570, Schilling added brackets.

- ^ Gudrun Wilcke: The children's and youth literature of the National Socialism as an instrument of ideological influence: song texts, stories and novels, school books, magazines, stage works. Lang, 2005, ISBN 3-631-54163-5 , p. 43 f.

- ↑ René Schilling: The "Heroes of the Wehrmacht" - Construction and Reception. In: Rolf-Dieter Müller, Hans-Erich Volkmann (Hrsg.): The Wehrmacht. Myth and Reality. Oldenbourg, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-486-56383-1 , p. 570 ff.

- ^ Bertrand Michael Buchmann: Austrians in the German Wehrmacht: Soldiers' everyday life in World War II. Böhlau Verlag, Vienna 2009, ISBN 978-3-205-78444-9 , p. 27.

- ↑ Two examples among many are: Wilhelm Müller: Möbius; 2009. 1984; Korbinian Viechter: As an infantryman to the Knight's Cross. Möbius, 2009, ISBN 978-3-00-019264-7 .

- ^ Christian Hartmann: Wehrmacht in the Eastern War: Front and Military Hinterland 1941/42. 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-486-70225-5 , pp. 178-180.

- ↑ Detlev Niemann: Evaluation Catalog Germany 3. ISBN 3-934001-00-9 , p. 527.

- ↑ Detlev Niemann: Evaluation Catalog Germany 3. ISBN 3-934001-00-9 , p. 527.

- ↑ Distinguishing features between Knight's Cross and EK II

- ↑ Uniform-Markt magazine . No. 16, year 1940, p. 126, appendix technical notes.

- ↑ Veit Scherzer: Knight's Cross bearers 1933-1945. Militaer-Verlag, Ranis / Jena, p. 62.

- ↑ Veit Scherzer: Knight's Cross bearers 1933-1945. Militaer-Verlag, Ranis / Jena, p. 64.

- ↑ Special regulations for medals and decorations previously awarded

- ↑ Walther-Peer Fellgiebel : The bearers of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross: 1939–1945. Podzun-Pallas, Friedberg / H. 1993, ISBN 3-7909-0284-5 , p. 6.

- ↑ RGBl. I 1939, p. 1573 : Ordinance on the renewal of the Iron Cross.

- ↑ after: Walther-Peer Fellgiebel: The bearers of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross: 1939–1945. Podzun-Pallas, Friedberg / H. 1993, ISBN 3-7909-0284-5 , p. 7.

- ↑ RGBl. I 1940, p. 849 : Ordinance amending the ordinance on the renewal of the Iron Cross.

- ↑ RGBl. I 1941, p. 613 : Second ordinance amending the ordinance on the renewal of the Iron Cross.

- ↑ RGBl. I 1945, p. 11 : Leader's decree on the foundation of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with the Golden Oak Leaves with Swords and Diamonds. and Third Ordinance amending the Ordinance on the Renewal of the Iron Cross.

- ^ Piper Verlag: Diaries Joseph Goebbels. Volume 4, 4th edition. 2008, p. 1383.

- ↑ a b Bodo Herzog: Provocative findings on the German submarine weapon. In: Historische Mitteilungen der Ranke-Gesellschaft 11 (1998), pp. 101–124, here pp. 105 f.

- ↑ Bodo Herzog: Knight's Cross and submarine weapon. Comments on award practice. In: Deutsches Schiffahrtsarchiv ISSN 0343-3668 10 (1987), pp. 245–260, here p. 254.

- ↑ Erich Murawski : The German Wehrmacht Report 1939-1945. A contribution to the study of intellectual warfare. Boppard am Rhein 1962, ( Writings of the Federal Archives. Volume 9), p. 43.

- ↑ Karl Dönitz: Ten years and twenty days. 4th edition Frankfurt a. M. 1967, p. 221.

- ↑ The military historian Jürgen Rohwer published for the first time in 1957 on the commander's successes and continued his investigations in the following years. Irrespective of these research results, authors such as Franz Kurowski (Bodo Herzog: Knight's Cross and U-Boat Weapon , p. 260, with reference to: Franz Kurowski: The bearers of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross of the U- Boat Weapon 1939-1945. The owners of the highest Award of the Second World War of the U-Bootwaffe. Podzun-Pallas, Friedberg / Hessen 1987, ISBN 3-7909-0321-3 ), Harald Busch (Bodo Herzog: Knight's Cross and U-Boot-Weapon , p. 257, with reference to: Harald Busch: This is how the U-boat war was. 4th edition, Schütz , Preussisch Oldendorf 1983, ISBN 3-87725-105-6 ), Wolfgang Frank (Bodo Herzog: Knight's Cross and U-Boat Weapon , p. 257, with reference to: Wolfgang Frank: The wolves and the admiral. U-boats in combat, triumph and tragedy. Bastei-Verlag Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1981, ISBN 3-404-65025-5 ) and Jochen Brennecke (Bodo Herzog: Ritterkreuz and U-Boot-Waffen , p. 259, with reference to: Jochen Brennecke: Jäger - Gejelte. German U-Boats 1939–1945. Koehler, Herford 1982, ISBN 3-7 822-0262-7 ) to the numbers of the Nazi propaganda.

- ↑ s. Die deutsche Luftfahrt , Jahrbuch 1941, Frankfurt / Main 1941, pp. 231, 234, 236; Jochen Prien: The fighter pilot associations of the German Air Force 1934 to 1945. Part 3. Eutin [2001], p. 347.

- ↑ Erich Murawski : The German Wehrmacht Report 1939-1945. A contribution to the study of intellectual warfare. Boppard am Rhein 1962, ( Writings of the Federal Archives. Volume 9), p. 73.

- ↑ Hildegard von Kotze (ed.): Heeresadjutant bei Hitler 1938–1943. Major Angel's Records. Stuttgart 1974, pp. 89f. (Hitler on November 4, 1940); Adolf Heusinger : Orders in conflict. Tübingen 1957, p. 98; s. a. Horst Boog: The German Air Force Command 1935 to 1945. Stuttgart 1982, p. 524.

- ↑ Karl Heinz Frieser: The battle in the Kursker Bogen , The German Empire and the Second World War , Volume 8, pp. 83–211, here p. 203.

- ^ Veit Scherzer: Knight's Cross bearers 1933-1945. Militaer-Verlag, Ranis / Jena, p. 30.

- ↑ Veit Scherzer: Knight's Cross bearers 1939-1945. Militaer-Verlag, Ranis / Jena 2005, ISBN 3-938845-00-7 , p. 22.

- ↑ Veit Scherzer: Knight's Cross bearers 1939-1945. Militaer-Verlag, Ranis / Jena 2005, ISBN 3-938845-00-7 , p. 103 ff.

- ↑ Veit Scherzer: Knight's Cross bearers 1939-1945. Militaer-Verlag, Ranis / Jena 2005, ISBN 3-938845-00-7 , p. 105 ff.

- ↑ after Walter-Peer Fellgiebel: The bearers of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939–1945. Friedberg 1993, ISBN 3-7909-0284-5 ; the OdR also follows this. Other sources speak of 7,175 (Scherzer), 7,318 and up to 7,361; including 73 foreigners.

- ↑ Michael Officer: From heroic leader to lonely deserter: On the change in the motives of masculinity in German war literature . Diplomica Verlag 2012, ISBN 3-8428-8495-8 , p. 51.

- ↑ Peter von Polenz: German language history from the late Middle Ages to the present . Volume 2, 17th and 18th centuries. Volume 3, 19th and 20th centuries, Verlag Walter de Gruyter, 1999, ISBN 3-11-014344-5 , p. 466.

- ^ Paul Schäfer: Bundeswehr and right-wing extremism . In: Science & Peace. Dossier 28, 2/98, ISSN 0947-3971

- ^ Jörg Nimmergut: Bibliography on German Phaleristics. (PDF; 549 kB)

- ↑ Information for the troops on dealing with the order community of knight cross bearers (OdR); Federal Ministry of Defense, Bonn on March 5, 1999: Quotation subject : Ban on contact with the Order of the Knight's Cross (OdR). The Federal Minister of Defense decided on March 4, 1999 that the Federal Armed Forces will no longer maintain official contacts with the OdR and its regional sub-organizations with immediate effect. The behavior and statements of the board of directors of the OdR towards the Bundeswehr are no longer acceptable. OdR events are no longer to be supported. This includes troop visits and the provision of rooms for events in facilities and properties of the Bundeswehr; Visits that have already been promised are to be canceled. Official representatives of the OdR are no longer invited to Bundeswehr events. The participation of active and retired soldiers in uniform in events of the OdR is prohibited. Requests by the OdR to support the commemoration of the dead can be granted after a case-by-case examination. The support is then limited to the provision of two honorary posts, a trumpeter and a drummer. The provisions of ZDv 10/8 (note outside the quotation: successor is the central guideline A2-2630 / 0-0-3 "Military forms and celebrations of the Bundeswehr"), according to which the funeral ceremonies for bearers of the Knight's Cross with the approval of the Federal Minister of Defense A small or large escort of honor can be made remain unaffected by this instruction. By order (signature)

- ^ Tabular curriculum vitae of Rudolf Scharping in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- ↑ Bundestag printed matter printed matter 14/1485 (PDF; 128 kB)

- ↑ Only brave soldiers? In: young world. October 13, 2004.

- ↑ The Knight's Cross bearers of Hameln. on: Spiegel online. 4th October 2004.

- ↑ Honor salary for knight cross bearers? The time of October 23, 1952.

- ↑ a b c Veit Scherzer: The knight cross bearers. Main volume, 2nd revised edition. Militaer-Verlag, Ranis / Jena 2007, ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2 , p. 9.

- ↑ Underlining in the original by Dörr. Veit Scherzer: The knight's cross bearers. Main volume, 2nd revised edition. Militaer-Verlag, Ranis / Jena 2007, ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2 , p. 8.

- ↑ Apabiz: Otto Riehs. A life for a lie

- ↑ Order of the Knight's Cross Bearers of the Iron Cross (ed.): Directory of members. Ordensgemeinschaft der Ritterkreuzträger des Eiserner Kreuz eV and Order of the Military Merit Cross 1914–18 eV Freiburg 1980, p. 3 and p. 49.

- ↑ To find u. A. in Walther-Peer Fellgiebel: The bearers of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross: 1939–1945. Podzun-Pallas, ISBN 3-7909-0284-5 , last page in the appendix.

- ↑ Veit Scherzer: The knight's cross bearers. Main volume, 2nd revised edition. Militaer-Verlag, Ranis / Jena 2007, ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2 , p. 54.

- ↑ Veit Scherzer: The knight's cross bearers. Main volume, 2nd revised edition. Militaer-Verlag, Ranis / Jena 2007, ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2 , p. 55, footnote 164.

- ↑ Walther-Peer Fellgiebel: The bearers of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross: 1939–1945. Podzun-Pallas, ISBN 3-7909-0284-5 , p. 18.

- ↑ To: August Berzen, Heinz Fiebig , Ernst Hollmann, Nikodemus Kliemann, Heinz Lotze, Herbert Schnocks, Gustav Schiemann, Johann Stützle, Hans Turnwald, Gustav Walle as well as Heinz-Oskar Laebe and Hermann Plocher. Cf. Veit Scherzer: The knight's cross bearers. Main volume, 2nd revised edition. Militaer-Verlag, Ranis / Jena 2007, ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2 , p. 55.

- ↑ Veit Scherzer: The knight's cross bearers. Main volume, 2nd revised edition. Militaer-Verlag, Ranis / Jena 2007, ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2 , p. 55f and appendix.

- ↑ Regardless of the WASt, other experts hold the same view with regard to the “Dönitz order”: “Because even at that time and under the law at that time, military orders could be issued through oral pronouncements (to whom?), But current legal norms could not be changed; the right then in force but looked - as it is in the nature of a religious ceremony - a decision of the will of the ceremony entitled in individual cases before "Off: Heinz Kirchner, Hermann Wilhelm Thiemann, Birgit Laitenberger, Dorothea Bickenbach, Maria Bassier. German medals and decorations. 6th edition. Carl Heymanns Verlag, Cologne 2005, ISBN 3-452-25954-4 , p. 134.

- ↑ a b Veit Scherzer: The knight's cross bearers. Main volume, 2nd revised edition. Militaer-Verlag, Ranis / Jena 2007, ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2 , p. 55f, footnote 167.

- ↑ Veit Scherzer: The knight's cross bearers. Main volume, 2nd revised edition. Militaer-Verlag, Ranis / Jena 2007, ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2 , p. 54, footnote 158.

- ^ Letter from Fellgiebel to Manfred Dörr, In: Veit Scherzer: Die Ritterkreuzträger. Main volume, 2nd revised edition. Militaer-Verlag, Ranis / Jena 2007, ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2 , p. 55, footnote 163.

- ↑ Veit Scherzer: Knight's Cross bearers 1939-1945. The holders of the Iron Cross of the Army, Air Force, Navy, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm and armed forces allied with Germany according to the documents of the Federal Archives. 2nd Edition. Scherzers Militaer-Verlag, Ranis / Jena 2007, ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2 .