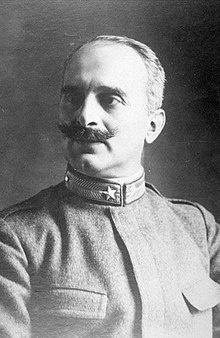

Giulio Douhet

Giulio Douhet (born May 30, 1869 in Caserta near Naples , † February 15, 1930 in Rome ) was an Italian general and theoretician of air warfare .

Live and act

Douhet, a contemporary of air war theorists William Mitchell and Hugh Trenchard , attended the Modena Military Academy and became a career officer in the artillery of the Italian Army . Later he studied engineering at the Polytechnic Institute in Turin.

As a general staff officer, he published textbooks on the motorization of the military around 1900 . With the introduction of airships and later airplanes in Italy, he quickly recognized the military potential of the new technology. Douhet viewed the connection of the air force to the army as a mistake and advocated the formation of an independent air force .

When the war for Libya broke out between Italy and Turkey in 1911 , aircraft were used for reconnaissance, target reconnaissance, transport and bombing for the first time. Douhet was commissioned to write a report on the aviation experience. He suggested that high-altitude bombing should be the aircraft's primary role. From 1912, while in command of the Italian Aviation Battalion in Turin, Douhet wrote a set of rules for the use of aircraft in war , one of the first of its kind.

In 1913 he took over command of the Battaglione Aviatori , which had been founded a year earlier and was one of the nucleus of the Italian Air Force. In the same year he met the young aircraft engineer Gianni Caproni , with whom he subsequently worked closely on expanding the air force

Douhet's insistence on air power marked him as a radical . In some ways he was reminiscent of another Italian thought leader, his contemporary Marinetti , the author of the Futurist Manifesto . After it became known that Douhet Caproni had commissioned the construction of bombers without authorization, he was transferred to the infantry.

When the First World War broke out , he called on Italy to start a massive armament program, primarily with aircraft. In order to achieve air sovereignty, the enemy would have to be made "harmless". He proposed a fleet of 500 bombers that could drop 125 tons a day, but was ignored.

When Italy entered the war in 1915, Douhet was shocked by the incompetence and poor preparation of the army. He criticized the conduct of the war with superiors and members of the government and was vehemently in favor of conducting an air war. An insulting letter eventually earned him an arrest and a military tribunal charge for spreading hoax and agitation. He was sentenced to one year in military prison.

Douhet continued to write about air power in his cell and sent messages to ministers suggesting a huge fleet of aircraft. Shortly after the disastrous Battle of Good Friday in 1917, he was released from prison and returned to service. As the bad news piled up, he was soon appointed head of the General Commissariat of Aviation, where he worked on improving Italy's air force.

Angered by his superiors, he left the army in 1918. After the war, his conviction was revoked by a court martial and Douhet was promoted to general. But instead of returning to service, he continued to publish his theories. In 1921 he completed a very influential treatise with the title Luftherrschaft ("Il Dominio dell'Aria").

The sentence “The bomber always gets through!” Is awarded to Douhet. Stanley Baldwin pronounced it in the British Parliament in 1932. Even if the sentence should not come from Douhet himself, it still aptly expresses his seminal views on modern air warfare. Douhet was the mastermind of the strategic bombing war and is counted among the leading early exponents of geopolitics. His influence was particularly great on the theory of aerial warfare in Great Britain and the USA , which was already evident in their air armament programs before and fully with the warfare of the two main Western powers during the Second World War .

Giulio Douhet died in February 1930 after a heart attack. He is buried with his wife Teresa (Gina) Casalis in the monumental cemetery Campo Verano in Rome.

See also

Web links

- Michael Eula: Giulio Douhet and Strategic Air Force Operations , in: Air University Review, September-October 1986

- Entry on Giulio Douhet in the personal lexicon of international relations virtual (PIBv), edited by Ulrich Menzel , Institute for Social Sciences at the Technical University of Braunschweig

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ulrich Menzel : Between idealism and realism. The doctrine of international relations. Frankfurt / M. 2001, p. 60.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Douhet, Giulio |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian general and air power strategist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 30, 1869 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Caserta near Naples |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 15, 1930 |

| Place of death | Rome |