Abyssinian War

| date | October 3, 1935 to November 27, 1941 |

|---|---|

| place | Abyssinia ( Ethiopia ) |

| Exit | Victory of Italy in the regular war until 1936/37; Stalemate in the guerrilla war until 1940; Italy was defeated in the East Africa campaign until 1941 |

| consequences | Italian de jure annexation of Abyssinia |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

Supported by: German Reich (1935–1936) United Kingdom (1940–1941) |

|

| Commander | |

|

|

|

| Troop strength | |

|

Maximum strength: approx. 250,000 soldiers |

Maximum strength: 330,000 Italian soldiers, |

| losses | |

|

350,000–760,000 Abyssinians killed (including time of occupation) |

25,000 military and civilian casualties |

The Abyssinian War was a war of aggression and conquest of the fascist Kingdom of Italy against the Empire of Abyssinia ( Ethiopia ) in East Africa, in violation of international law . The armed conflict that began on October 3, 1935 was the last and largest colonial campaign of conquest in history. At the same time it was the first war between sovereign states of the League of Nations , which a fascist regime waged to gain new "living space" ( spazio vitale ). Italy thus triggered the worst international crisis since the end of the First World War .

The Italian attack started with a pincer offensive without a declaration of war : in the north from the colony of Eritrea and in the south from Italian Somaliland . The Abyssinian armed forces offered bitter resistance, but in the end could not stop the advance of the numerically, technologically and organizationally superior Italian invasion army. After the fall of the capital Addis Ababa , Italy declared the war over on May 9, 1936 and formally incorporated Abyssinia into the newly formed colony of Italian East Africa . In fact, the Italians controlled only a third of the Abyssinian territory at that time; Fighting with remnants of the imperial army continued until February 19, 1937. Subsequently, the Abyssinian resistance waged a guerrilla war , which passed into the East Africa campaign on June 10, 1940 with the Italian entry into the Second World War and ended with the complete victory of the Allied- Abyssinian liberation troops on November 27, 1941.

In military history , the Abyssinian War marked the breakthrough of a new, particularly brutal form of warfare . Italy used chemical weapons of mass destruction on a large scale and waged the most massive air war in history to date . In this context, the civilian population and field hospitals of the Red Cross were also targeted . Viceroy Rodolfo Graziani (1936–1937) established a reign of terror in the Italian occupied territory , during which the elites of the old empire were systematically murdered by the fascists. In this context, research also speaks of the “first fascist war of extermination ” and compares the politics of Italy with the initial phase of the later German terrorist occupation in Poland . Graziani's successor Amedeo von Savoyen-Aosta (1937–1941) reduced the repression. At the same time, a racist apartheid regime was developed, and Italy continued to use chemical weapons against "rebels". In total, around 350,000 to 760,000 Abyssinians were killed as a result of the Italian invasion and occupation from 1935 to 1941.

After 1945, Ethiopia tried to set up an international tribunal for Italian war criminals based on the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials , but failed not only because of resistance from Italy, but especially because of that of the western allies. Thus, no Italian perpetrator has ever been prosecuted for war crimes committed in Ethiopia. The Italian government did not officially admit the systematic use of poison gas until 1996, and in 1997 Italian President Oscar Luigi Scalfaro apologized in Ethiopia for the injustice caused from 1935 to 1941. Today's Ethiopia commemorates fascist rule with two national holidays, “Martyrs Day” on February 19th and “Liberation Day” on May 5th.

description

In German-language research, the Italian attack on the Ethiopian Empire from 1935 on is called the "Abyssinian War", while in Italian literature it is treated as the "Second Italian-Ethiopian War". The conflict between Italy and Ethiopia of 1895/96 is considered the " First Italian-Ethiopian War ". In English-language research, the terms “Ethiopian war” or “War in Abyssinia” are used, which are also rendered as “Ethiopian War” in works translated into German.

prehistory

Situation of the Abyssinian Empire

At the time of the Italian invasion, the Abyssinian Empire (Ethiopia) was considered the “oldest genuinely African empire”. Its old heartland in northern Ethiopia had developed from the ancient empire of Aksum , whose inhabitants had converted to Christianity as early as the 4th century . Favored by its seclusion and the tenacious self-assertion of its inhabitants, an archaic social system survived in this mountainous country, shielded from deserts and dry savannas, until the 20th century. The cultural and political supremacy of this Abyssinian high culture were held by the ethnic groups of the Amharen and Tigray who lived in the northern ancestral land and who regarded themselves as the peoples of the country. Ethiopia only received its present-day borders under Emperor Menelik II (1886–1913). The Negus Negesti ( "King of Kings") continued the policy of expansion, begun under his predecessors in his long reign. This brought Menelik II the reputation of a " black imperialist" and let countless peoples and tribes come under Abyssinian rule until the Christian peoples of the northern highlands finally found themselves as a minority in their own state. At the same time, Menelik II established the modern imperial central state with the Amharic as the lingua franca , the capital Addis Ababa , founded in 1886 , the "Bank of Ethiopia" with a national currency and other reforms.

In the age of high imperialism , the historical development of the great Ethiopian empire was also in danger. However, at the Battle of Adua in 1896, Menelik II's army managed to repel the first Italian attempt at conquest. The victory over the Italian expeditionary force secured the independence of the empire and ensured that Abyssinia was the only African state besides Liberia to be spared colonial rule. In addition, the victory of Adua left the fate of the country in the hands of the Amharic and Tigrin upper classes as well as the Ethiopian Orthodox Church . The Kushitic tribes of the south and the Nilotic peoples in the west and south-west were enslaved by the Christian state peoples, in 1914 an estimated one third of the entire population was living as slaves . In summary, the Ethiopia of the early 20th century is considered to be a large, multi-ethnic state with a feudal-like social structure, a backward country with a narrow economic base, a premodern education system, a poor transport system and a military organization based on feudal foot and rider contingents. In addition, there was conflicting coexistence between the dominant north and the rest of the empire, between the central government in Addis Ababa and the peoples in the periphery.

Ras Tafari Makonnen , who has been regent since 1916 , continued the course of authoritarian modernization. He worked nominally under Empress Zauditu , a daughter of Menelik, but rose during his 14-year reign to the strong man of the monarchy. Japan's path to modernity served as a model for his radical reforms. Ras Tafari modernized the administration, created new ministries, brought in a well-trained leadership elite, secularized and renewed the education system, built roads and hospitals, expanded the communication network and, from 1918, resolutely opposed the slave trade. In March 1924, his government officially abolished slavery. With the ban, slavery did not disappear immediately in Ethiopia, but it did defuse a major image problem that had so far badly damaged Abyssinia's reputation in the world. The fluent French-speaking regent pursued a foreign policy based on the Western powers, which aimed to free Abyssinia from its isolation. This course was rewarded in 1923, when the empire was the only African country to be accepted into the League of Nations with full rights and its independence was finally recognized internationally.

After Zauditu's death in 1930 he was crowned the new emperor, Ras Tafari took the throne name Haile Selassie I (“Power of the Trinity”) and from then on ruled Abyssinia alone. He did everything in his power to strengthen the imperial central power against the competing provincial powers. This process was supported by the constitution of July 16, 1931 . Based on Japan's constitution of 1889 , it was the first ever written constitution of the Empire of Abyssinia. In an unprecedented way it strengthened the emperor's decision-making prerogative and concentrated all power in his hands, with which he now resembled an absolutist monarch. The succession to the throne was limited to Haile Selassie's family, thus turning Abyssinia into a hereditary monarchy . The two chambers of the newly created parliament were of no real importance. Although the 1931 constitution strengthened national unity, the empire was finally transformed into an autocracy. In the last three years before the Italian attack, Haile Selassie I continued the modernization policy that had been initiated. Particular attention was paid to the construction of telephone lines and the first Abyssinian radio station was set up in 1931. At the same time, the Abyssinia government opened up to the world market and intensified trade relations with foreign countries.

Italian colonialism and fascism

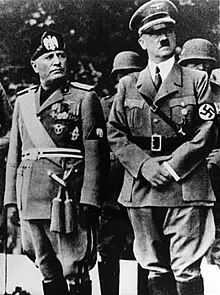

When Benito Mussolini's fascists came to power in 1922, Italian colonialism received an enormous boost. In their agenda, practiced as a political religion , the fascists called for a totalitarian state and advocated a social Darwinist- based racism , pronounced militarism , a glorification of war and the ideal of restoring the power and glory of the ancient Roman Empire . This made the Italian attack on the Ethiopian Empire only a matter of time. Abyssinia militarily humiliated Italy in Adua in 1896 and stood as a symbol of the permanent frustration of Italy's colonial ambitions. In addition, Ethiopia was still independent and was therefore open to conquest. The conquest of Ethiopia was only intended to be a first step in a much larger imperial expansion program. The original fascist goal of Italian supremacy in the Mediterranean ( mare nostrum ) has been increasingly replaced by a planned "advance on the oceans" since the 1930s.

As early as the 1920s, the Italian fascists waged so-called "pacification wars" against the breakaway colonies of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica in North Africa ( Second Italian-Libyan War ) and against Italian Somaliland in East Africa ( colonial war in Italian Somaliland ). The war in Libya in particular became a test field for new war methods and weapons as well as a “school of violence”. In Libya, for example, chemical warfare agents were thrown from the air for the first time in 1923, and arbitrary mass executions were also part of the repression measures. In total, around 100,000 of the around 800,000 Libyans fell victim to the colonial war, around 40,000 of them in Italian concentration camps during the genocide in Cyrenaica . In March 1932, just a few weeks after the completion of the military operations in Libya, Colonial Minister Emilio De Bono undertook a trip to Eritrea agreed with Mussolini to discuss the situation there for a future war against Abyssinia. Despite his critical conclusion that an "armed intervention" would require a long preparation time and devour huge sums of money, De Bono came to the view in the weeks after his return to Italy that Italy had to look for its "colonial future" in East Africa. In the summer of 1932 De Bono commissioned the commander of the Italian troops in Eritrea to work out a military attack plan against Abyssinia. In autumn 1932, on the tenth anniversary of the fascist takeover of power, De Bono had enough illustrative material and strategic preliminary studies to obtain the green light from Mussolini for a comprehensive military strike against the Abyssinian Empire.

War preparations

As the victorious power of the First World War , Italy was able to advance the development of its military clout unhindered in the 1920s. Italy, whose chemical weapons arsenal had been modestly exempted during the First World War, intensified its efforts in this area since the transfer of power to the fascists. On July 10, 1923, a "chemical military service" ( Servizio chimico militare ), subordinate to the Ministry of War, was launched, which controlled and coordinated all, even civilian research and development projects in this area. This organization soon included a staff of around 200 officers and numerous scientists who worked in special research departments. In contrast to the Weimar Republic , where the manufacture and import of chemical warfare agents was strictly forbidden by the Versailles Peace Treaty , chemical armament in Italy was by no means secret. In May 1935, Benito Mussolini took part in large-scale maneuvers at the Centocelle airport near Rome, which were all about chemical warfare. During this exercise, special forces demonstrated the throwing of gas hand grenades, methods of land poisoning, the overcoming of mustard gas barriers by gas-protected troops and the detoxification of contaminated terrain. In the field of chemical warfare agents, the Italian armed forces had reached a remarkably high level within a few years. In the mid-1930s, they were considered to be the first-rate power in this area around the world.

In early 1934, the Italian military planned, contrary to all international treaties signed by Italy, to use chemical warfare agents in a war with Ethiopia. At the end of December 1934 it was Mussolini who prepared the Italian army for a poison gas use in a memorandum. In April 1935 the construction of a total of 18 chemical warfare depots was ordered in the Italian colonies of Eritrea and Somalia. In February, the Italian Air Force General and Undersecretary of State in the Aviation Ministry Giuseppe Valle had given the order to prepare 250 aircraft for the dropping of poison gas bombs. In the summer of 1935, the establishment of a chemical ordnance force for East Africa began. In total, over 1700 men of the Servizio chimico militare under the command of General Aurelio Ricchetti were mobilized for the Abyssinian War .

In the 1930s, Abyssinia also took steps to modernize the army, which in terms of organization and armament had more or less remained at the level of the Battle of Adua. The main thing was that it consisted of a decentrally organized rider and foot contingent commanded by provincial princes. It consisted of traditionally armed warriors who had little in common with the modern equipped soldiers of European land forces. In addition, an Imperial Guard of several thousand men existed as the core of a standing army, the only well-trained and reasonably modern armed unit. In order to professionalize the training of the troops, Belgian instructors were brought into the country and in 1934 a military academy for officer candidates was founded. Of course, Abyssinia did not have its own production facilities for modern military equipment. Therefore, the imperial government acquired rifles, machine guns, anti-aircraft cannons, ammunition and some obsolete combat aircraft on the international arms market. Nevertheless, there could be no question of forced armament. The country's material resources were far too limited for that.

From July 1934 to September 1935, Fascist Italy made diplomatic and economic preparations for war. Mussolini tried to get the approval of Britain and France, and took advantage of every small border incident to create a climate of nationalist excitement in Italy and mobilize more soldiers. The economy was reorganized with a series of measures in view of the war: On July 31, 1935, strategically important raw materials such as coal, copper, tin and nickel were monopolized by the state. The "General Commissariat for War Production" was set up, which now included 876 factories and 580,000 Italian workers. On July 6, 1935, Mussolini told his soldiers in the city of Eboli : “We don't give a damn about all negroes of the present, past and future and their possible defenders. It will not be long before the five continents will have to bow their heads to the fascist will. "

In 1935 the Ethiopian army numbered around 200,000 men, a few hundred machine guns, a few artillery pieces and a handful of aircraft. On the Italian side, the Colonial Minister and Supreme Commander, General Emilio De Bono , were subordinate to a total of 170,000 Italian soldiers, 65,000 African colonial troops ( Askaris ) and around 38,000 workers in the autumn of 1935 . Under his successor, Marshal Pietro Badoglio , around 330,000 Italian soldiers, 87,000 Askaris and around 100,000 Italian workers fought and worked in March 1936. The logistical resources included 90,000 pack animals and 14,000 motorized vehicles of various categories from passenger cars to trucks. The invading army of Fascist Italy also received 250 tanks, 350 aircraft and 1,100 artillery pieces by sea. Italian daily gasoline consumption exceeded Italy's total fuel consumption during World War I. The Italian Navy, which was mainly responsible for the transport of people and construction and war material, carried around 900,000 people and several hundred thousand tons of material during the war.

The "War of the Seven Months" (1935–1936)

Italian advance and trench warfare

Without declaring war, the Italian units passed the Mareb River on the night of October 2 to 3, 1935 , which marked the border between Eritrea and Abyssinia. Also on October 3, the Italian Air Force began bombing the operational targets Adigrat and Adua . Emperor Haile Selassie, who was in the capital Addis Ababa, had tried to create a buffer zone by withdrawing the army by 30 kilometers in order to avoid a military escalation. But after crossing the border, the Negus officially proclaimed general mobilization in the empire. The three Italian army corps of 30,000 each set off at the same time, but from different points of departure. While the 1st Army Corps under General Ruggero Santini was advancing from the Eritrean Senafe to Adigrat, the 2nd Army Corps, commanded by General Alessandro Pirzio Biroli , moved to Adua and the Eritrean Army Corps of General Pietro Maravigna , made up of Askaris and Italian black shirts , moved in Direction Inticho (Enticciò).

On the Abyssinian side, Emperor Haile Selassie transferred the command of the northern troops to Ras Kassa, one of the most important dignitaries of the empire. Under his command, the units of the Rase Immirù, Sejum and Mulughieta fought an initially unsuccessful defensive battle. Almost unhindered by the Abyssinian forces, which were previously largely withdrawn, the Italians achieved successes of high symbolic power in the first few days. On October 5th, General Santini's troops hoisted the Italian tricolor on the Fort of Adigrat, which had been abandoned after its defeat in the First Italo-Ethiopian War in 1896. On October 6th, Adua was taken, the conquest of which was one of the main objectives of the Italian offensive. A week later, Axum , the cradle of Abyssinian culture, fell. The first phase of the war was completed in the north under De Bono on November 8, 1935 with the capture of the village of Mekelle (Macallè). This step was significant in several ways. With Mekelle, the seat of government of East Tigrè had been conquered, and important caravan connections from Dessiè and Lake Asciangi led to the town.

- The fighting terrain of Abyssinia

In relation to the available forces of 110,000 men, De Bono had opened up a fairly extensive front line on the northern front with three widely spaced attack wedges. After the great land gains of the first weeks of the war, he saw the most urgent task in fortifying the conquered positions, securing the connections between the attack wedges, wiping out pockets of resistance and bringing in supplies. Fearing that another advance would provoke dangerous evasion attacks in the rear of his own units, he slowed the pace of the attack at the beginning of November and stopped it completely at Mekelle in mid-November. This militarily considered approach aroused the displeasure of Mussolini, who viewed it as an unauthorized and unauthorized departure from the strategy of offensive war. On November 11, the dictator ordered De Bono's units to advance a further 50 kilometers to the Amba Alagi , that is, to extend the front to a total of 500 kilometers. The old general, who considered further extension of the line of operations to be a military "mistake", resisted. It is true that Mussolini finally agreed with his fascist companion in terms of content and approved the temporary standstill on Mekelle's line. De Bono's defiant demeanor, however, found Mussolini unacceptable, and so he replaced him - still promoted to Marshal - on November 14th by the incumbent Chief of Staff Pietro Badoglio.

The second phase of the war lasted from mid-November to mid-December 1935. It was dominated by a positional war . The new Commander-in-Chief Badoglio had been informed of his appointment on November 15 in the Palazzo Venezia . Accompanied by his two sons, who served as air force pilots, Badoglio arrived in Massaua from the port of Naples on November 26th. From there he went to Adigrat, where the seat of the Italian high command was. After an inspection tour which he had undertaken at the beginning of the hostilities in the theater of war, the Chief of Staff was already informed about the situation in East Africa. He did not judge her much differently than his predecessor. For the time being, he did not order any new offensives either. After the first weeks of the war had led the invading army on the northern front 200 kilometers into enemy territory and the deployment of the Abyssinian army had meanwhile been completed, Pietro Badoglio did everything in his power to secure the conquered areas against all eventualities and to keep the advanced line of operations at Makalle. The fighting force should no longer hover in the air, he justified his measures against the dictator.

In the context of the two-front war, the units operating on the southern front were assigned the task of binding enemy forces and thus improving the chances of success for the main thrust in the north in the operational plans. Nevertheless, General Rodolfo Graziani, experienced in the desert war, put everything on the offensive from the start. The ambitious officer did not want to resign himself to the fact that he had been chosen as the commander of a secondary theater of war. That is why his units attacked across the entire front width of 1,100 kilometers. In the first few days they occupied Dolo and Oddo. Gorrahei was captured on November 5th. Then they met the resistance of the Abyssinian Southern Army. Supported by heavy rainfall, which softened the dirt roads and made them impassable for heavy military equipment, the troops of Ras Desta Damtù and Degiac Nasibù managed to stop the advance of the enemy units into the desert highlands of the Ogaden.

Abyssinian Christmas Offensive and Badoglio's "Unbounded War Violence"

Badoglio had taken over the command of De Bono in a strategically difficult situation. His armed forces were split in two, one at Adua and one at Mekelle. Although only 100 kilometers apart, there was no direct communication between the two units. The units at Adua had to be supplied via two mule tracks that could be cut off by the Ethiopians, and the flanks of the troops at Mekelle were wide open. While Badoglio concentrated on flank security, he had the center guarded by only four Black Shirt divisions. In this situation, the third phase of the war began in mid-December and lasted well into January 1936. In the midst of the war of positions, which was preparing a major offensive that would make the difference in the war, troops of the Imperial Northern Army under the command of Ras Kassa unexpectedly launched relief attacks. In the center, the black shirts were pushed back, and Badoglio had to call in additional Eritrean units for reinforcement.

The Italian armed forces had to evacuate some of their outposts, give up passports they controlled and withdraw from towns that were already occupied. In particular, the units commanded by Ras Immirù , with up to 40,000 Abyssinian soldiers on the right flank of the Italians, advanced far into territory in the province of Tigray that had already been believed to be lost and came as far as the vicinity of Axum. The "Gran Sasso" division had to withdraw as far as Axum, while the units from Ras Immirù near Dembeguinà even managed a small victory in a field battle. It became increasingly clear that the Italians had overstretched the lines of operations during their rapid advance and that they were by no means controlling the rear of the army. With the onset of the Abyssinian counter-offensive, partisan activity behind the Italian lines also increased. Ambushes loomed everywhere. On the right-hand sector of the front, the Italian soldiers often did not know from which direction the Abyssinians would attack. These were able to achieve considerable success at times and brought the invaders on various sections of the front in dire straits, which aroused memories of the defeat of Adua among the invaders.

In this decisive phase, the “war became unbounded”. To stop the Ethiopian advance, Commander-in-Chief Pietro Badoglio decided to wage a chemical war on a large scale. As units from Ras Immirù were about to cross the Takazze River , fighter planes dropped Yperite bombs on human targets for the first time on December 22nd. This mission took place without official authorization from Rome. It was not until December 28 that Mussolini officially authorized Badoglio to order the dumping of all kinds of poisonous gas “also on a large scale” ( anche su larga scala ). A few days earlier, the dictator had authorized General Rodolfo Graziani on the southern front to use highly toxic substances. There, on December 24th, three Caproni bombers flew the first poison gas attack. A large herd of cattle and camels grazing near the village of Areri was bombed. From now on the chemical weapon of mass destruction was integrated into most of the Italian operations. Until the fall of Addis Ababa, there was massive and systematic use of poison gas on both fronts. Although they ultimately did not resolve the conflict, the Yperit attacks by the Air Force ushered in the turn of the war. They brought the Abyssinian Christmas offensive to a standstill and helped to bomb the way south.

After the Abyssinian Christmas offensive had been stopped with the most brutal means, the fourth phase of the war began in mid-January 1936; it lasted until the capture of Addis Ababa on May 5th. A severely brutalized warfare, which in addition to the deployment of chemical warfare agents also included the burning of entire areas, the slaughter of the herds of cattle and numerous massacres, now shaped the conflict. After securing his supplies and receiving three additional divisions from Mussolini, Badoglio was ready for his offensive. Opposite him were three Ethiopian armies. On the right flank at Adua stood Ras Immirù with 40,000 men, in the center Ras Kassa and Ras Sejum with 30,000 men and on the left flank Ras Mulughieta with 80,000 men. Between January and May 1936 there were massive clashes between the war opponents. The First Tembi Battle, the Battle of Endertà (Inderta), the Second Tembi Battle, the Battle of Scirè and the decisive battle on Lake Asciangi at Mai Ceu (Maychew) took place on the northern front. In the latter case, the Imperial Guard was wiped out.

Although the war was decided on the northern front, heavy fighting also broke out in the south and southeast. In contrast to the Abyssinian commanders in the north, who belonged to the traditional ruling class of the empire, General Graziani faced commanders of the younger generation here: Ras Desta Damtu in the south and Dejazmach Nasibu Za-Emanuel as governor of Harrar in the southeast. After the capture of Neghelli, Graziani's Italian troops launched the great offensive in the Ogaden area and captured the city of Harrar. In all of these battles and maneuvers, an interaction of the air force with the motorized ground troops and the light infantry proved its worth on the Italian side. The Italians also benefited from the relatively good organization and logistics. A large part of the replenishment was carried out via the repaired connecting routes, which were hastily created in day and night work, as well as via air bridges.

League of Nations and International Reactions

The Abyssinian War triggered the worst international crisis since the end of the First World War and presented the League of Nations with the greatest test since it was founded. Two member states faced each other in the military conflict. For the first time since the Japanese occupation of Manchuria in 1931, the League of Nations was confronted with a lawbreaker who defied the principles of the “civilized world” and fundamentally called the system of collective security into question. According to Article 16 of its statutes, aggression constituted an act of war against the international community as a whole. The Ethiopian government left no stone unturned to report the Italian acts of violence to the League of Nations and to have them condemned. This approach was the only promising strategy for the militarily defeated country. Just a few weeks after Ual-Ual, Ethiopia asked the League of Nations for mediation and for several months tried to achieve a non-violent settlement of the conflict, in which Italy never showed any real interest.

As early as October 7, 1935, the League of Nations Assembly condemned Italy as an aggressor and thereby blamed the country for the outbreak of hostilities. A few days later, it also imposed economic and financial sanctions by 50 votes in favor, with three abstentions from Italy's neighbors Austria, Hungary and Albania. They came into force on November 18, but were so mild compared to the possible punitive measures that they did not hinder Italy in its warfare. Neither the embargo on arms, ammunition and military equipment nor the credit freeze had a strong effect, and the trade embargo exempted goods essential to the war effort such as oil, iron, steel and coal. In addition, Italy could easily acquire all the raw materials and goods it needed from states that did not belong to the League of Nations. No one in Geneva seriously considered closing the Suez Canal to Italian warships or a military intervention.

Throughout the hostilities there were several initiatives by Abyssia before the League of Nations. In his telegram of December 30, 1935, Emperor Haile Selassie I protested sharply against the Italian use of poison gas for the first time. The emperor branded them as “inhumane practices” and charged that they, in conjunction with other war crimes, aimed at the “systematic extermination of the civilian population”. This set the tone that ran through almost all diplomatic interventions by the imperial government like a red thread. At the Geneva headquarters of the League of Nations, the Abyssinian government made two specific demands for weeks: First, it asked for financial support in order to be able to buy arms and armaments on the world market. Second, she called for the sanctions to be extended to include essential items such as oil, iron and steel.

The position of National Socialist Germany stood in sharp contrast to the position of the British and French democracies . Hitler had adopted an ideology related to fascist Italy. Mussolini, however, was not prepared to tolerate a German annexation of Austria, which would have made Nazi Germany a direct neighbor of Italy on the Brenner Pass . The German dictator, determined to expand into southern Austria, concluded that, should Mussolini be victorious in Abyssinia, he would be in a strong enough position to counter Germany's ambitions. At the same time, Mussolini would not be able to do so as long as his army was involved in an African war. The German Führer was therefore anxious to strengthen the Abyssinian resistance and responded benevolently to Abyssinian requests for help to the Germans. This made the German Reich practically the only country that supported Abyssinia. Without Mussolini's knowledge, Haile Selassie's army was supplied with three aircraft, over sixty cannons, 10,000 Mauser rifles and 10 million cartridges from the German side.

Course of the war after the proclamation of the empire

The proclamation of the Italian Empire on May 9, 1936, with which the Italian King Victor Emmanuel III. assumed the title of "Emperor of Abyssinia" was a diplomatic expediency to announce the de jure conquest of Abyssinia before the world . In fact, at that time, the Italians controlled only a third of the Abyssinian territory, which included most of the large cities and some important transport axes. Furthermore, huge areas in central, western and southern Ethiopia were completely under Abyssinian control. The Abyssinian troops remaining in these zones did not surrender, and the local population did not recognize the authority of the occupying power either. In the following five years Italy tried to conquer the remaining areas, in which around 25,000 resistance fighters were constantly under arms. Large parts of north and north-west Abyssinia, however, were permanently beyond Italian control. In 1936, 1937 and 1938/39, Italy had 446,000, 237,000 and 280,000 soldiers, respectively, available to conquer and control the Abyssinian territories. The Ethiopian resistance after May 1936, whose supporters called themselves “patriots” (Amharic arbagnoch ), can be divided into two phases: The first lasted until February 1937 and was essentially a continuation of the war. A few high commanders of the imperial army were dominant, namely Ras Immirù, Ras Desta Damtù and the Kassa brothers, the three sons of the former commander-in-chief on the northern front. The subsequent second phase was marked by a transition from the resistance movement to guerrilla warfare, which was mostly led by members of the lower Abyssinian nobility.

Continuation of the regular war (1936–1937)

After Haile Selassie I fled into exile in Britain, an Abyssinian counter-government was formed in the western Ethiopian city of Gore. This was in loose connection with the emperor and had two main tasks: On the one hand, it was supposed to create a political counter-body that would delegitimize the Italian occupation. On the other hand, she was entrusted with the organization and coordination of the ongoing Abyssinian resistance. The government in Gore was officially headed by Bitwoded Wolde Tzadek. The most important figure in authority, however, was Ras Immiru, who was considered the most capable general of the Abyssinian army and who had appointed the Emperor Haile Selassie as his viceroy in Abyssinia before he went into exile. In Gore, the Ras received particular support from the Black Lions Organization - a resistance group made up of military and civilian intellectuals. The actions of the "patriots" showed a considerable degree of efficiency, despite the fact that central coordination never succeeded.

On May 12, while Badoglio was holding the Victory Parade in Addis Ababa, a column of trucks belonging to the Italian Air Force was attacked by "patriots" and almost completely destroyed. A similar action by the resistance took place two days later. Badoglio responded by sending six Eritrean battalions to the rural outskirts of the capital to carry out “retaliatory measures”. Military operations of this kind were supported by Mussolini, who told Badoglio, in relation to the policy of retaliation, that "we must sin by excess, not by lack". In June 1936, Graziani, as the new viceroy, received the order from Mussolini to occupy southwestern Ethiopia in one fell swoop in order to accelerate the recognition of the Italian empire. The territory called "Gouvernement Galla-Sidama" by the Italians was the most fertile agricultural area and had significant mineral resources. In addition, Great Britain was interested in maintaining a zone of influence in this region. Due to a lack of troops and the onset of the rainy season, Graziani opposed a quick offensive. He argued that Addis Ababa did not have enough troops to defend itself, and because the roads were damaged by the rain, the incoming reinforcements were not on the ground quickly enough. The offensive against southwest Abyssinia was therefore postponed to October after the end of the rainy season.

The Abyssinian resistance made several ambitious attempts to retake Addis Ababa during the 1936 rainy season. This was intended to halt the Italian advance into western Ethiopia and to strengthen the government of Gore. Ras Immiru and Wolde Tzadek made the first attempt, advancing from the cities of Ambo and Waliso to the capital in June. However, the company failed due to resistance from the local Oromo population, who refused to allow the Abyssinian troops to march through. Due to the previous repression in the Empire, the Oromo were hostile to the Gore government. Ras Immiru had to withdraw with his soldiers to southwest Ethiopia, where he finally surrendered to the Italians in Kaffa and was deported to Italy. On July 28 and 29, 1936, the second Abyssinian attack on Addis Ababa took place, this time from the northwest: the two Kassa brothers Aberra (Abarra) and Asfa Wassen, the sons of Ras Kassa, who had over 10,000 soldiers in their headquarters in the city of Fiche decreed, around 5,000 "patriots" besieged the capital. Their units penetrated into the city center, where they encountered fierce resistance from the entrenched occupiers, and were finally pushed back with the help of the Italian air force. A month later, on August 26, another Abyssinian commander, Dejazmach Balcha, led the third unsuccessful offensive from the southwest. But the struggle for Addis Ababa had made it clear how insecure Italian rule still was.

In order to make attacks of this kind impossible in the future, Viceroy Graziani had a barbed wire fence secured by machine gun nests around the capital, the gates of which were only opened during the day for security reasons. After the failure of a direct capture of Addis Ababa, the "patriots" tried to cut off the capital from supplies via the railway line to Djibouti. During the rainy season, this was the only and therefore vital supply route. Under Dejazmach Fikre Mariam, 2,000 Abyssinian fighters attacked the railway line with automatic firearms . The most daring action of this kind by the resistance took place on October 11, 1936, when an armored train carrying Colonial Minister Alessandro Lessona was fired at by "patriots" for half a day in the village of Akaki, despite the strictest secrecy. The Italians used tanks and over a hundred aircraft to secure the supply line, and guards were set up every 50 meters along the entire railway line. This made it clear again that the Italian occupying power did not have Abyssinia under control.

In the meantime Graziani had begun what was known as the “great colonial police operation” against the remaining Abyssinian military leaders. Again, massive aerial bombardments and poison gas were used. Initially, the Italians turned against the three Kassa brothers in the central Ethiopian region of Shewa : Wonde Wassen Kassa set out on September 6, 1936 with 1,500 armed warriors from the city of Lalibela to unite with his two brothers against the Italians in the city of Fiche . His unit was intercepted by Italian troops, and on December 11, 1936, Wonde Wassen Kassa was executed. His two brothers, Aberra and Asfa Wassen, were promised a pardon in the event of surrender. However, they were arrested by General Tracchia, who occupied Fiche with 14,000 soldiers, and executed on December 21, 1936. After the military operations against the "patriots" in the Shewa region, Graziani's focus turned to Ras Desta Damtu, who delayed the Italian conquest of southern Ethiopia with an army of over 10,000 men. After an expired ultimatum, the Italians attacked Desta Damtus units with three military columns and over 50 aircraft in the Arbegona region (Arbagoma) on January 18, 1937. Both the air force and ground troops were given a free hand to completely destroy the Abyssinian army. At the Battle of Jebano on February 2, the Abyssinians suffered heavy losses and Desta Damtu lost one of his generals. From February 18 to 19, 1937, the last open field battle of the war took place near the town of Goggeti (Gojetti). The Ethiopian units were wiped out by the Italians. Ras Desta Damtu himself managed to escape, but was arrested on February 24 by a unit collaborating with the Italians and then shot.

Guerrilla War in Italian East Africa (1937–1940)

With the death of Ras Desta Damtu, the Italians had eliminated all the great Abyssinian military leaders by the spring of 1937. In the meantime they had also taken the city of Gore and driven out the provisional Abyssinian government. The prospect of a control of Abyssia was however thwarted with the terrorist wave of the fascists in the pogrom of Addis Ababa that broke out at the same time . On February 19, 1937, two young members of the Abyssinian resistance, Abraha Daboch and Mogas Asgadom, attempted an assassination attempt on Viceroy Graziani in Addis Ababa. After its failure, the Italian occupying power, and especially the fascist party militia of the Black Shirts, reacted with days of mass murders against the black population of the capital. This Italian act of violence initiated the transition to the second phase of the Abyssinian resistance: the nationwide guerrilla war , with a focus on the Amhara governorate.

The security situation was so tense in 1937 that Viceroy Graziani was unable to consent to the rapid and massive withdrawal of troops requested by Rome because of military necessity. Since August 15, 1937, Italian troops in the Amharic regions of Gojjam and Begemeder were attacked, besieged, destroyed or captured by "patriots". The most famous guerrilla leaders were Abebe Aregai, Haile Mariam Mammo, Dejazmach Tashoma Shankut and Fitawrari Auraris. In the Amharic unrest regions of Shewa, Begemder and especially Gojjam they successfully attacked Italian units and convoys, besieged enemy fortifications and carried out acts of sabotage. On the high plateau, which was ideally suited for guerrilla tactics, it was teeming with small and large herds of resistance. In September 1937, a popular uprising against the Italian occupation forces finally began in Gojjam. This resulted on the one hand from the massive repression in the previous months, on the other hand in the devastation of the land and forced disarmament of the population by the Italians. The agrarian Ethiopian society regarded the possession of land and weapons as inalienable rights, the abolition of which could not be tolerated. At the end of 1937 the resistance of the "patriots" of the Gojjam region had isolated the Italians in their fortifications. In his last report as Viceroy, Graziani had to admit to Mussolini on December 21, 1937 that more than 13,000 soldiers had died on the Italian side since the capture of Addis Ababa - many thousands more than in the "War of the Seven Months" itself.

The new viceroy of Italian East Africa, Amadeus von Aosta, tried to soften the brutality of his predecessor and to rely on a colonial policy based more on cooperation with the local elite. In contrast, the new commander in chief of the Italian armed forces in East Africa, General Ugo Cavallero, continued the use of poison gas in the governorates of Amhara and Shewa. In view of the open rebellion in these parts of the country with around 15,000 armed men, as well as several thousand in the Oroma-Sidama governorate, Cavallero set out on a campaign of reconquest against the Gojjam region in Amhara. To this end, he developed a network of roads running through the area and set up 73 military camps along the district boundaries to cut off Gojjam from the outside world. The military action that began in the spring of 1938 claimed around 2,500 to 5,000 deaths among the resistance fighters, but did not result in the population being subjugated. A second campaign was launched northwest of Shewa Province, killing around 2,000 rebels, but the leader of the local revolt escaped. In the following year, 1939, a military stalemate finally set in, which led to a decline in actions by the Abyssinian resistance. The Italians had failed in the suppression of the Abyssinian guerrilla war, but the latter were unable to take the well-fortified Italian positions. On the eve of the Second World War, on the outbreak of which the resistance movement relied, the Italians lost around 10,000 men and around 140,000 wounded.

Internationalization of the war and liberation (1940-1941)

The conflict reached its final and decisive stage in the course of its internationalization after fascist Italy entered World War II at the beginning of June 1940 on the side of the German Reich. In July 1940, Italian troops advanced from Italian East Africa against the British colony of Kenya and the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan , capturing some towns and cities near the border. After France's military collapse, an armistice was concluded with its colony Djibouti , which granted Italy extensive powers for the duration of the war, including the use of the port facilities in French territory. In August 1940 , Italian troops captured British Somaliland . Italy controlled the whole of the Horn of Africa for a short time. On September 13, an army of 150,000 men commanded by Marshal Rodolfo Graziani attacked British units in Egypt from Libya . However, the Italian offensive stopped after a few days. The British counterattacked in December and crossed the border with Libya on January 2nd. The failure of the Italian "parallel war" forced National Socialist Germany to provide aid. Since February 1941, the " German Africa Corps " was established in Libya under Lieutenant General Erwin Rommel . All of this heralded the end of sovereign Italy, which, in the wake of its military defeats, increasingly declined to a subordinate brother-in-arms of Germany, which Berlin no longer took seriously.

The Italian offensives in Africa forced Great Britain, which had favored the Italian conquest of Ethiopia through its appeasement policy and officially recognized the conditions created by armed violence in East Africa in 1938, to radically change its policy. The Italians not only threatened some British possessions and areas of influence in Africa (Sudan, Kenya, Somaliland, Egypt), but also the sea route to India, the Achilles' heel of the Empire. It was only because of this threat that Prime Minister Winston Churchill decided to provide military support to the Ethiopian resistance. British arms aid proved crucial to the liberation. In January 1941, the British unleashed three attacks on Italian East Africa almost simultaneously. The first attack was carried out by Anglo-Indian troops under General William Platt from Sudan. They penetrated into Eritrea and fought their way into the Tigray. The second offensive, also from Sudan, was started 500 kilometers south and targeted the province of Gojjam. Emperor Haile Selassie I, who had returned from exile and had waited for further developments in Khartoum in Sudan, also took part in it. Together with the British commanders Daniel A. Sandford and Orde Wingate , he was at the head of the Gideon Force , a small brigade of British and Ethiopian troops. Together with the "patriots" of the Gojjam province, the Gideon Force advanced against the Blue Nile and Addis Ababa. The third attack was carried out by soldiers of General Alan Cunningham , who marched into Somalia from Kenya, captured the capital Mogadishu and from there slowly fought their way through Harrar against Addis Ababa.

With combined forces, the British and Abyssinian troops succeeded in bringing the Italian occupiers from Ethiopia into severe distress. The Ethiopian "patriots" played an important role during the liberation campaign. In their previous four-year struggle, they had done a great deal to tire the enemy occupying forces. Now, having received military support from the British, they went on the offensive. With British air support they marched through the Gojjam region and played an important role in the conquest of the city of Bure (Buryé). The army of the "Patriots" was advancing so quickly that the British command posts feared that the Abyssinians would reach the capital before their armed forces and endanger the European inhabitants living there. Therefore, the air support for the "Patriots" was ended again. In the Shewa region, Ras Abebe Aragai , whose resistance continued throughout the occupation, surrounded the capital Addis Ababa with his troops. Cunningham's troops reached the capital on April 6, 1941.

Exactly five years after Marshal Pietro Badoglio took Addis Ababa, Emperor Haile Selassie moved into the liberated center of his empire on May 5, 1941. Abyssinian armed forces of the "Patriots" were also involved in the conquest of many other cities in Ethiopia in the following months. After some bitter resistance, the Italian occupation forces surrendered unconditionally on May 19. Viceroy Amadeus of Savoy, who had holed up with his remaining troops at Mount Amba Alagi, went into British captivity. The last battle of the war took place in Gondar on November 27, 1941. On this day the garrison of General Guglielmo Nasi also had to surrender. Ethiopia, which was the first sovereign nation to fall victim to fascist aggression in the 1930s, was thus also the first fascist-occupied country to be liberated with Allied help in 1941.

Warfare and war crimes

The air war

The Abyssinian War saw the most massive and brutal air force deployment the world had seen up to that point, marking a crucial stage in the history of modern air warfare . In the theater of war in the Horn of Africa, far more people were killed in air bombardment in 1935/36 than in all previous conflicts combined. While the Luftwaffe was still at an experimental stage during World War I and was only used as an "auxiliary weapon", the air forces of all European countries then rose to become independent armed forces alongside the army and navy. The ever greater ranges and attack speeds, but also the extremely increased weapon effect of the bomber plane fundamentally changed the nature of the war. The bomber plane was a symbol and product of the dawning high-tech age.

The bombing of the Adua and Adigrat settlements on October 3, 1935 marked the beginning of the military air force deployment in East Africa. Based on the air raids on villages and provincial towns, a variant of the action was pursued in the first months of the war that was already foreseen in the tangible war plans against the Ethiopian Empire from 1932/33. The deliberate destruction of the villages did not correspond to an ad hoc decision by the High Commissioner Emilio De Bono, but was planned well in advance. This strategy was later retained in principle under the command of Pietro Badoglio. Although Badoglio in mid-February 1936 did not consider the use of bacteriological weapons to be necessary in the further course of the war, the general pleaded until February 29, 1936 for a “decisive terrorist operation from the air on all centers in the Shewa region , including the capital to carry out ". The question of the bombing of the capital or the railway line between Addis Ababa and Djibouti proved to be of great relevance throughout the war and preoccupied not only those in charge of the military in East Africa, but also Mussolini and international diplomacy. Ultimately, it is mainly due to political reasons that Addis Ababa and the railway line were largely spared during the war, although in both cases the destruction was planned first.

Nowhere else was the military imbalance between Italy and Abyssinia more apparent than in the air force. In total, an armada of 450 combat aircraft was deployed in the Horn of Africa - around half of the total number of the Italian Air Force. Three quarters of the air fleet moved to East Africa consisted of bombers. The aviation forces, commanded by General Mario Ajmone Cat , flew hundreds of attacks during which they dropped tens of thousands of fragmentation, incendiary and gas bombs on enemy targets. From the beginning of the war, the Italian Regia Aeronautica completely dominated the airspace over Abyssinia. The few aviators on the Abyssinian side were either not operational or were destroyed on the ground shortly after the start of hostilities.

The heavy air raid on Dessiè , the provincial capital of Wollo , became a symbol of this new warfare . It was carried out on December 16, 1935 by 18 aircraft in two waves of attack. They destroyed numerous buildings and civil facilities as well as a hospital run by American Adventists . Most of the 50 people killed in the attack were civilians. The provincial cities of Neghelli, Jijiga and Harrar were also relatively heavily devastated by Italian aircraft . Adigrat , Adua, Quoram, Gorahei, Debre Markos , Sassa Baneh, Degeh Bur and others were hit a little more easily . Not least because of the violent international reactions after the heavy air strikes on the provincial cities, Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa (Dire Daua), the most militarily profitable bomb targets, were not attacked from the air. At Mussolini's instructions, the capital was to be excluded from terrorist attacks because of the foreigners residing there. The strategic bombings of Abyssinian population centers were among the first in history. Although they cost a few hundred deaths in the worst case, according to Aram Mattioli (2005), as systematically carried out acts of war, they already pointed to “the area bombing of the Second World War that devoured people”.

Attacks on the Red Cross

The Italian air strikes against field hospitals of the Red Cross are also considered unprecedented acts of violence. Recent research has shown a total of 15 attacks on Red Cross facilities, mainly on field hospitals, in the four months between December 6, 1935 and March 29, 1936. Seven of these were deliberately carried out, and eight more were side effects of air strikes aimed at other targets. The Swedish mission was hardest hit at Melka Dida on the southern front. The purely medical facility was 25 kilometers behind the front and 7 kilometers from the headquarters of Ras Desta Damtù. On December 30, 1935, the well-marked camp was attacked in several waves by ten fighter planes. Yperite grenades were also used. As a result of the bombing rain, 42 people were killed, most of them patients.

Fascist Italy accused Abyssinia of systematically abusing the Red Cross symbol for civil and military purposes. Both allegations were widely spread through fascist diplomacy, press and propaganda. The Italian allegations, however, had little substance. Individual cases were often misinterpreted, exaggerated or inadmissibly generalized by the fascist propaganda. According to Rainer Baudendistel (2006), the Italians fell victim to their own strategy. Since for them the Abyssinian War was a war between unequal, between a civilized nation and a people of barbarians, there could and should not be any communication between the two. As a result, the Italian high command accepted bombing the Red Cross rather than clarifying exactly whether the possible target was a regular field hospital or not.

In total, the Italian air strikes caused 47 fatalities, several dozen wounded and great material damage such as the destruction of the only Red Cross aircraft that was in service on the Abyssinian side. The Air Force dropped more than 10 tons of bombs, including 252 kilograms of mustard gas bombs, over the Red Cross. The fact that there were no more victims to complain about is considered a stroke of luck for the Red Cross helpers. The Italian air strikes against the Red Cross were based on a pattern. The further the field hospitals advanced towards the Abyssinian front and the more they got in the way of Italian operations, the greater the risk of being bombed. Practically all foreign and Abyssinian field hospitals that came into such a situation had to experience this. The hospitals, on the other hand, which were at a safe distance from the front, remained unscathed, although they were regularly overflown by Italian war planes. This refutes the Abyssinian allegation that the Red Cross was systematically bombed by the Italians.

The poison gas war

Warfare agents, technology, areas of application

Italy used three chemical warfare agents in Abyssinia: arsenic , phosgene and yperite , which - filled in gas bombs - were dropped by fighter planes. In addition, poison gas grenades were used to an unknown extent, which were prepared on site and whose use, in contrast to the gas bombs dropped by the Air Force, was largely not documented. One of the few documented exceptions was the heavy artillery bombardment of the Amba Aradam with arsenic shells in February 1936 . The Italian Air Force used explosive devices of various sizes and designs. The main role was played by yperite, known as "mustard gas", which was the most toxic known warfare agent in the mid-1930s. Even fatal in the smallest concentrations, yperite, as an oily and pungent smelling skin poison , leads to an agonizing death or severe injuries within several hours.

The heavy, torpedo-shaped bomb C.500.T. became the symbol of the brutal Italian Yperit mission. With a total weight of 280 kilograms, it contained a total of 212 kilograms of mustard gas. This large-caliber explosive device was specially developed for the conditions in East Africa and was used there in particular on the northern front. After being dropped by fighter planes, the almost head-high bomb was detonated using a time fuse at a height of 250 meters above the ground. Depending on the wind strength, a fine rain of warfare agents with a length of 500 to 800 meters and a diameter of 100 to 200 meters came down. In accordance with the military successes, the air force took on the central role in the gas war. The aircraft types Caproni Ca.111, Caproni Ca.133 and Savoia-Marchetti SM.81 had already been equipped with suitable suspension devices for gas bombs in the workshop. The powerful bombers had been developed in 1932 and 1935, had a range between 980 and 2,275 kilometers, had several machine guns on board and had a cargo capacity of 800 kilograms to two tons. Both the Caproni bomber and the Siai-Marchetti S. 81 were later used in the Spanish Civil War and World War II.

The use of chemical warfare agents, which had an offensive character from the start, brought a new dimension to the Abyssinian War. In the course of the war, however, the arsenic shells used by the artillery proved to be less effective than the poison gas bombs of various calibres dropped from the air. At the tactical and strategic level, the effects of the use of poison gas were enormous. As the Italian armed forces were informed, thanks to the intelligence service, about which routes the Abyssinian armies were choosing, when they would move and where the headquarters were set up, it was possible, for example, to set up “chemical blockades” on passes or at river crossings. After being dropped, the closed areas proved to be impassable for the Italians for three to five days, which could have serious consequences depending on the time pressure of the maneuvers. Especially on the southern front, where Graziani urged to advance as quickly as possible, this "side effect" of the tactical use of poison gas was problematic. The resolutions formulated at the beginning of the war not to hit the civilian population or to keep the gas bombs for large targets were given up after just a few weeks. Pilots bombed even the smallest gatherings of people, caravans and herds of cattle with explosives, incendiary bombs and poison gas, especially on the southern front.

The chemical warfare agents were supposed to terrorize the enemy, limit his operational planning and break the morale of the enemy units and the civilian population. On March 2, 1936, Mussolini released all the cities of Ethiopia for bombing, with the exception of Addis Ababa and the Dire Dawa railway junction. This decision was made after Badoglio had called for “terrorist action by the air force over the Ethiopian centers, including the capital” a few days earlier. Regarding the gas war, Mussolini admitted his generals "to use any poison in any quantity given the enemy's war methods", but with regard to the city bombing he repeated his protective directive against Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa several times, but only towards the end of the campaign still had a formal character.

Abyssinia had little to oppose the chemical warfare of the Italian armed forces. The Ethiopian army also expected the gas war, but without being able to assess the dimensions of the new warfare. The Ethiopian government gave the commanders instructions on how to behave in the event of a plane attack or suspected poison gas. In order to instruct the soldiers, who are often ignorant of reading, German manuals on the gas war were translated into the Amharic language and provided with many hand-drawn sketches. The Ethiopian army had hardly any means at its disposal against the use of poison gas. Most of the soldiers in the imperial army went into battle barefoot and had neither protective suits nor special shoes or gas masks that would have kept the fine rain of warfare agents away, including through hard rubber , or allowed them to cross contaminated terrain. Only the imperial guard had a few thousand gas masks, which proved to be of very little use against mustard gas. There was no medical service in the imperial army that could have alleviated the suffering of the poison gas victims. The civilian population was defenselessly exposed to the devastation from the air. As in all of Africa, there were no shelters in Ethiopia, nor did the people possess rudimentary protective knowledge, not to mention gas masks. There was no detox.

Extent of the use of poisonous gas

It is difficult to say exactly how many poison gas bombs have been used in Ethiopia. It is also difficult to determine which bombs were filled with which weapons. On the northern front, the Luftwaffe dropped around 1,020 C.500.T bombs from December 22, 1935 to March 29, 1936, which corresponds to a total of around 300 tons of yperite. In addition, Badoglio had 1,367 artillery shells filled with arsenic fired at the Abyssinian soldiers during the Battle of the Amba Aradam (February 11-15, 1936). On the southern front, between December 24, 1935 and April 27, 1936, the Luftwaffe dropped 95 C.500.T bombs, 172 to 186 21 kilogram yperite bombs and 302 to 325 phosgene bombs, totaling around 44 tons Poison gas corresponds. For the period from December 22, 1935 to April 27, 1936, this results in a total of around 350 tons of poison gas. From 1936 to 1939 about 500 more poison gas bombs were dropped on the Abyssinian resistance. Therefore, during the entire period of the Italian war of aggression and the occupation from 1935 to 1941, according to conservative estimates, the Ethiopians suffered 2,100 poison gas bombs or around 500 tons of poison gas. As a consequence, historians speak of a “massive gas war”.

Most of the C.500.T bombs were dropped on the northern front until the First Tembi Battle. In the battle itself, around three times fewer yperite bombs were dropped than in the previous period. In the period up to the next battle, that of Endertà, the number of bombs dropped increased massively and in the battle itself was roughly the same as in the First Tembi Battle. In the interval between the next battle, the number of bombs dropped increased again. In the Second Tembi Battle, the Italian Air Force used relatively few C.500.T bombs and possibly did without them at the Battle of Scirè. The gas war on the southern front looked different than on the northern front. In contrast to the northern front, several different types of yperite bombs and also phosgene bombs were used in the south. In addition, there were many skirmishes on the southern front, but only two major military confrontations: when taking the town of Neghelli and during the Harrar offensive. The operations from the air always preceded those on the ground. The tendency not to limit the bombings with the C.500.T bombs to the period of the battles thus existed on both the northern and southern fronts. The gas war also proved to be a constant in the south.

After the proclamation of the empire, Mussolini gave Viceroy Graziani again on June 8, 1936 the use of poison gas to extinguish armed revolts. Until the end of November 1936, months after the official proclamation of Italian East Africa, not a month passed without the Italian Air Force deploying 7 to 38 C.500.T explosive devices over Abyssinia. Until Viceroy Graziani was replaced in December 1937, poison gas continued to be used regularly in all regions of Ethiopia. Under Graziani's successor, Duke Amadeus of Aosta, poison gas bombs were mainly used in the governors of Amhara and Shewa. The commander in chief of the Italian troops in Italian East Africa, General Ugo Cavallero , who was a supporter of Graziani's approach to eradicating the Ethiopian resistance, was in charge. Yperite and arsenic shells were also used on Cavallero's orders in the Zeret massacre in April 1939. In late autumn 1940, an Italian plane released poison gas over a rebel camp, killing five resistance fighters and seriously injuring many more.

Contrary to rumors that quickly found their way into the international press, the Italian troops did not use chemical warfare agents from the start in the Abyssinian War. The first missions were flown shortly before Christmas 1935 as a result of the Abyssinian counter-offensive. It was only this threatening situation that led the Italian high command to drop its previous considerations. The Italian Air Force also did not allow Yperit to be randomly spread over villages, towns and crowds, and moreover did not use spray planes to contaminate large areas of agricultural land. Mussolini assumed that this final delimitation of the war would have caused more political damage than military benefit internationally. Although the gas attacks were mostly directed against armed units in contested areas, they were carried out without any consideration for the civilian population. By the end of 1936 alone, several thousand, perhaps even tens of thousands, Abyssinians were killed by poison gas, and countless others were mutilated or blinded.

Biological weapons

According to the current state of research, no biological weapons were used in the Abyssinian War. However, their use was originally intended as an integral part of Italian warfare. Although until then no country in the world had used such, Mussolini thought openly of the use of bacterial cultures in February 1936. Ras Kassa's Abyssinian troops had previously put pressure on Badoglio's army on the northern front. Badoglio, however, pleaded against the use of bacteriological agents, because less the opposing combat units than the civilian population would have been affected by these measures. In addition, if bacteria were used, the Italians' offensive would have come to a standstill because entire areas would have been contaminated. As a final reason for not further radicalizing warfare, the general stated that the use of bacteria would provoke violent protests in the world and that further-reaching sanctions by the League of Nations, such as the oil embargo, could not be ruled out. Mussolini agreed with Badoglio's remarks. According to Giulia Brogini Künzi (2006), one can ultimately only speculate how bacteriological warfare in East Africa would have looked in practice. What is certain is that the Italian medical services had the armed forces and the population in the already conquered areas vaccinated against typhus and cholera . However, this measure could also have served as a general preventive measure in isolation from military considerations.

Destruction of livestock and the ecosystem

Since the Ethiopian troops could not fight in the long term without the support of the population because they were dependent on the information and local resources, the Italian warfare aimed at the destruction of all militarily useful elements such as the herds of cattle . With the extermination of tens of thousands of herd animals , the Italian military pursued the double goal of cutting off the food supply to the Ethiopian army and disciplining the civilian population or forcing them to leave the contested territory. A real hunt for livestock has begun on both fronts, as meat has traditionally been the basic foodstuff for most of the residents. The sheep, goats, camels and cattle were not only the food source, but also the capital of the nomads in the south of the country. On the southern front, the herds of cattle were systematically attacked from aircraft with explosives and poison gas bombs. Graziani abandoned his original plans to attack only "big targets" in favor of a blanket scorched earth strategy. From December 1935, small and very small groups of people and animals were also hit, unless it could be ruled out that they were of importance to the enemy.

A comparable way of gaining an advantage through direct intervention in the living space was the targeted burning of landscapes. Forests, steppe areas or rivers were set on fire with incendiary bombs and petrol so that Abyssinian riflemen could no longer hide in the shade of the trees. For the Swiss historian Giulia Brogini Künzi (2006), this procedure can almost be viewed as a forerunner of the chemical defoliants that were used later in the Vietnam War . In addition, the Italian generals contaminated rivers and water points with poison gas. Countless farmers and animals perished when they drank contaminated water. General Graziani in particular used this type of warfare on the southern front. On January 24, 1936, he instructed a squadron to cremate a forest in which enemy units had hidden after a battle with gas and incendiary bombs: “Set on fire and destroy what is flammable and destructible. Clean up everything that can be cleaned up. ”The damage to the ecosystem and the destruction of communities has reached a dimension, especially in the south, which justifies speaking of deliberate action by the Italians.

Exploitation of ethnic and religious conflicts

The Italians systematically capitalized on the ethnic and religious tensions between the conquered peoples. As early as the Second Italo-Libyan War from 1922 to 1932, Fascist Italy deployed Christian Askari colonial troops from Eritrea against the Muslim resistance. In the Abyssinian War, the "Libia" division commanded by General Guglielmo Nasi, which consisted of North African Muslims, was deployed. It went into action on April 15, 1936 and took part in Graziani's final offensive in Ogaden . By relocating Libyan mercenaries to the southern front, the fascist regime enabled them to avenge themselves for years of past acts of violence perpetrated on their families by Askaris from Eritrea during the fascist "reconquest of Libya". Muslim units of the "Libia" division were instrumental in conquering the cave-rich area of Wadi Corràc on the southern front, cutting off their opponents' escape route and then killing 3,000 Ethiopians. Graziani commented: “Few prisoners, in line with the custom of the Libyan troops.” The murder of prisoners continued at the watering holes in Bircùt, Sagàg, Dagamedò and in Dagahbùr. In view of the cruelty of the Askari, General Nasi, who was less radical than Graziani, promised his Libyan units a bounty of 100 lire for every prisoner alive. The “Libia” division ultimately made 500 Ethiopian prisoners who were then interned in the Danane concentration camp.

During the occupation, members of the Oromo ethnic group were incited against other ethnic groups by the Italians . As a result, the Oromo, who collaborated with the occupying forces, killed and mutilated many peasants of other ethnicities, cutting off women's breasts and men's genitals.

Execution of prisoners of war

Already during the "war of the seven months" the vehemently advancing Italians took hardly any prisoners. In large numbers, these would have put additional strain on the company's logistics, which were already heavily burdened. Deployed Abyssinian soldiers were often shot on the spot or executed after disclosing military information. Even fighters who surrendered voluntarily could not count on leniency or hope for compliance with the 1929 Geneva Convention on the Treatment of Prisoners of War . The annexation of Ethiopia by Italy had the effect that from then on Rome could regard all resistance fighters as "rebels" against the legitimate order and punish them harshly. On June 5, 1936, Mussolini ordered all “rebels” captured immediately to be shot. According to Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano, Achille Starace , commander-in-chief in the Abyssinian region of Gondar, not only had prisoners shot but also used them as targets for heart shots: “He shot them first in the genitals and then in the chest. Eyewitnesses reported these details. "

Crimes of occupation of Italy

Recent research has confirmed and expanded the picture of Italian occupation crimes drawn by pioneers such as Angelo Del Boca and Giorgio Rochat on the basis of a great deal of new information. Some massacres were forgotten for a long time, while the number of victims had to be revised upwards significantly for others. Already during the "War of the Seven Months" in 1935/36, especially since the change of command to Pietro Badoglio, there were regular serious attacks against the local population in the areas occupied by the Italian armed forces. These included rape, massacre, looting, the desecration of Ethiopian Orthodox churches and the burning of entire villages. The violence against the civilian population on some sections of the front became so widespread that Commander-in-Chief Pietro Badoglio felt compelled to intervene against these practices. In January and February 1936, for example, he called on General Alessandro Pirzio Biroli to keep the troops listening to his command in check: "If we continue like this, the whole population will rebel against us."

Nevertheless, a few days after the capture of Addis Ababa, Badoglio also subjected the capital to an initial "cleansing", which resulted in a wave of executions with around 1,500 deaths. At Mussolini's orders, members of the young educated class (“Young Ethiopians”), whom the dictator described as “conceited and cruel barbarians”, were to be liquidated. On July 30, 1936, Abuna Petros, one of the highest dignitaries of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, was shot dead by Italian Carabinieri in a public square in Addis Ababa . After the proclamation of the empire, Rodolfo Graziani was appointed viceroy to Badoglio and established a reign of terror in the Italian occupied territory with the approval of Rome. On July 8, 1936, Mussolini authorized the viceroy to carry out targeted mass murder of civilians as well: “I authorize Your Excellency again to systematically begin and lead a policy of terror and extermination against the rebels and the complicit population. Without the law on retribution 1 to 10, the plague cannot be mastered in the necessary time. ”In a similar way, Colonial Minister Alessandro Lessona of Graziani called for the“ use of extreme means ”. The most common forms of execution were hangings and shootings, other methods also included burning entire families in their homes with flamethrowers or beheading them. The display of chopped-off heads impaled on long lances on streets was intended to act as a deterrent.

In Italian East Africa, the terror of occupation emanated not only from regular members of the army, but also from the fascist militia ( black shirts ), from police units of the Carabinieri and from African colonial troops ( Askaris ). Members of the Abyssinian resistance and dissidents were mostly not imprisoned, but were often executed immediately after their capture. Only a few hundred high-ranking members of the Ethiopian aristocracy were given a chance of survival in prison. 400 of them were deported to Italy on Mussolini's orders and sentenced to exile there. In addition, the Italian oppressive apparatus in East Africa also used concentration camps , although this camp system was much more pronounced than previously assumed by research. Up until now, the literature has spoken almost exclusively of two concentration camps: The Danane camp was established in Italian Somaliland in 1935, and the Nocra camp in Eritrea in 1936 . Up to 1941, up to 10,000 prisoners, including women and children, were interned in the two penal camps . Because of the catastrophic conditions prevailing in both institutions and the very high death rates, historians also classify them as death camps . As part of a more recent research project, a total of 57 camps were documented in Italian East Africa, 35 of them in Ethiopia, 14 in Eritrea and 8 in Somalia. With the two camps in Ethiopia, Shano and Ambo, the existence of two camps was also documented which "served the sole purpose of eliminating the prisoners".

The most serious occupation crimes occurred in the period after the bomb attack on Viceroy Graziani, which provided the pretext for summary executions and massacres. During a ceremony in front of the viceroy's official residence in Addis Ababa on February 19, 1937, hand grenades shot Graziani, the Italian occupation elite, seriously injured. Some soldiers died. As a result, the local fascist party leader Guido Cortese began the three-day pogrom in Addis Ababa , in which, according to the first comprehensive account by Ian Campbell (2017), mainly fascist black shirts murdered around 19,200 people. Within a very short time, the capital lost up to 20% of its inhabitants, with fascist death squads also taking targeted action against the Abyssinian intelligentsia. After the failed attack on the viceroy, repression made a qualitative and quantitative leap. Graziani now extended the terror of the occupation to entire sections of the population whom he considered "dangerous" and accused of anti-Italian attitudes.