Cushitic languages

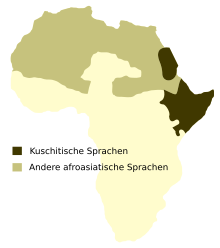

The Cushitic languages are a primary branch of the Afro-Asian language family and are spoken in northeastern Africa , especially in the Horn of Africa .

The most important individual languages are Oromo, spoken by around 30 million people, and Somali , the national language of Somalia, spoken by at least 12 million . Other Cushitic languages, each with over a million speakers, are Sidama , Hadiyya , Bedscha and Afar .

classification

The Cushitic languages comprise eight smaller units that are generally recognized, but their relationships with one another are controversial.

The Bedscha spoken in Egypt, Eritrea and Sudan is mostly classified as North Cushitic, but sometimes it is separated from Cushitic as a separate primary branch of Afro-Asian. The Dullay languages , Yaaku , the Highland East Cushitic languages and the Lowland East Cushitic languages are mostly combined to form East Cushitic , which thus forms the largest group within Cushitic. The togetherness of the group is, however, doubted by some scientists. For Südkuschitischen expects Ehret 1980, spoken in Kenya and Tanzania Rift languages that Dahalo and Mbugu Language , a kuschitisch- Bantu - mixed language . The Dahalo is also included in East Cushite; some researchers count the Rift languages as lowland East Kushitic, so that South Kushitic would be omitted. The Agaw or Central Cushitic comprises several languages in the Ethiopian highlands , including Bilen and Awngi .

This gives the following classification (Agaw according to Appleyard 2006, Südkuschitisch according to Ehret 1980. The controversial groups are in italics):

- North Cushi: Bedscha

- Agaw (Central Shushite Table )

- East Kushite

-

South Kushite

- Dahalo

- Mbugu

- Rift languages : Iraqw u. a.

Traditionally, the omotic languages were also counted as West Cushitic to Cushitic; However, most scientists today consider this to be a separate primary branch of Afro-Asian. The Ongota is also occasionally counted as Cushitic.

Research and classification history

The first scientific studies on Cushitic languages go back to Job Ludolf (1624–1704), who dealt with the Ethiosemitic as well as the Cushitic Oromo . The first larger representations of Cushitic languages, again of Oromo, were published by Karl Tuschtek and Johann Ludwig Krapf between 1840 and 1845. At the same time, other languages of East Africa became known in Europe, which turned out to be related to Oromo. The expanded knowledge of Cushitic soon made it possible to recognize these languages as related to Semitic and some North African languages. Richard Lepsius for the first time summarized East Cushitic languages and the Bedscha under the designation “Cushitic” as a sub-unit of “ Hamitic ”, a forerunner of today's Afro-Asian. At the end of the 19th century, the Austrian Leo Reinisch presented more precise descriptions of a further eight Cushitic and one Omotic languages . He also tried for the first time a subclassification of the Cushitic, but this turned out to be incorrect. In the first half of the 20th century, Italian researchers in particular made outstanding contributions to the description of new languages and comparative language research. Among them, Martino Mario Moreno deserves particular mention, who proposed a new classification in 1940, the main features of which are still valid today:

- ani-ati languages

- North Cushi: Bedscha

- Central Shushite Table

- East Kushite

- Low Kuschitisch

- Burji Sadamo

- Other groups

- ta-ne languages

- West Kushite

- Yamna

- Ometo

- Himira

- Gonga

- West Kushite

The subdivision into ani-ati and ta-ne languages was based on the different forms of the personal pronouns of the 1st and 2nd person, which are just one of the numerous serious differences between "West Cushit" and the rest. In the course of his reclassification of the languages of Africa, Joseph Greenberg also assigned a number of languages spoken in Kenya and Tanzania as "South Cushite"; In 1969 Harold Fleming separated “West Kushitic” from Cushitic and classified it under the name “ Omotic ” as a separate primary branch of Afro-Asian. In the second half of the 20th century, advances were made in the subclassification of East Kushitic, which was still very roughly outlined in Moreno's classification.

Phonology

Consonants

In 1987 Ehret reconstructed a proto-Kushitic consonant inventory. Like the pharyngeal fricatives are also available for the Cushitic glottalized sounds for the Afro-Asiatic generally [ ʕ ] and [ ħ ] and characteristic only in Südkuschitischen to-find lateral fricatives. In addition, larger parts of the Kushitic also have labiovelars.

Vowels

In Bedscha, East Kushitic, South Kushitic and perhaps also in Proto-Cushitic there is a five-level system with an opposition long - short: a - e - i - o - u - aa - ee - ii - oo - uu. In the Agaw, the vowels æ, ə can also be found, there is no distinctive meaning for the vowel quantity. It should be noted, however, that these correspondences are mainly typological in nature and the genetic correspondences between the individual language systems are more complex and less known.

volume

In almost all Cushitic languages, the tone has a distinctive meaning; most systems include a tweeter and a neutral tone; sometimes there are also contour tones. Often the tone only marks grammatical distinctions, as in Bedscha kítaab "book" - kitáb "books", but it can also have a lexical meaning, as minimal pairs like Somali béer "liver" - beér "garden" show.

morphology

Nominal morphology

In nominal morphology, there is a great diversity in Cushitic, but there are still commonalities that it shares with other primary branches of Afro-Asian.

In general, Cushitic has the two genera masculine and feminine , the numbers singular and plural, and sometimes several cases . The feminine is marked with an element t in the majority of languages , compare Bedscha ʾoor "son" - ʾoor-t "daughter", Somali wiil-ka "boy" (masculine) - beer-ta "garden" (feminine), Oromo thrush-essa "rich" (masculine) - thrush-ettii "rich" (feminine). In contrast to the mostly unmarked singular, there are various means of forming the plural: However, secondary singulatives can also be formed from the meaning after plural nouns through suffixes , see for example Awnji bún "coffee" - búna "coffee bean".

In Proto-Cushitic there were two or three cases, which were marked at least in masculine by the suffixes - a in the absolute and - u / i in the nominative . The existence of a genitive on - i is less likely.

Verbal morphology

Prefix conjugation

In Bedscha and East Kushitic there is a conjugation by means of prefixed person markers . That this is an archaism is shown by the fact that this prefix conjugation is restricted to certain verbs, but can also be found in Berber and Semitic. Several aspects / modes are distinguished by ablaut and infixes . The Bedscha has a very complex system with temporal, modal and aspectual distinctions, which must be seen to a large extent as an innovation. In the East Cushitic languages, on the other hand, only a perfect / past tense and a present / past tense, sometimes also a subjunctive / jussive, are formed. The conjugation of the verb "devour" is in the Afar:

| Perfect | Past tense | Subjunctive | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1. | unḍuʿ-e | anḍuʿ-e | anḍaʿ-u | |

| 2. | t-unḍuʿ-e | t-anḍuʿ-e | t-anḍaʿ-u | ||

| 3. | m. | y-unḍuʿ-e | y-anḍuʿ-e | y-anḍaʿ-u | |

| f. | t-unḍuʿ-e | t-anḍuʿ-e | t-anḍaʿ-u | ||

| Plural | 1. | n-unḍuʿ-e | n-anḍuʿ-e | n-anḍaʿ-u | |

| 2. | t-unḍuʿ-en | t-anḍuʿ-en | t-anḍaʿ-un | ||

| 3. | y-unḍuʿ-en | y-anḍuʿ-en | y-anḍaʿ-un | ||

Suffix conjugation

The prefix conjugation was pushed back in all Kushitic languages by a Kushitic innovation: the Kushitic suffix conjugation, in which the conjugation takes place with suffixed personal endings . Despite the outward similarity, it is generally believed not to be genetically related to Afro-Asian suffix conjugation. According to a theory proposed by Franz Prätorius at the end of the 19th century , their personal endings go back to a prefix-conjugated copula . There are major differences between the various languages with regard to the suffix-conjugated tenses, modes and aspects. While Somali, for example, can form a multitude of differentiated forms, the system of Oromo, which is also Eastern Cushit, is very simple and also has similarities with the ablaut relationships of the prefix conjugation (perfect e , imperfect a , subjunctive u ), which is why it could be particularly archaic ( déem "go"):

| Perfect | Past tense | Subjunctive | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1. | déem-e | déem-a | déem-u | |

| 2. | déem-te | déem-ta | déem-tu | ||

| 3. | m. | déem-e | déem-a | déem-u | |

| f. | déem-te | déem-ti | déem-tu | ||

| Plural | 1. | déem-ne | déem-na | déem-nu | |

| 2. | déem-tan | déem-tani | déem-tani | ||

| 3. | déem-an | déem-ani | déem-ani | ||

Derivation

Using affixes, derived verbs can be formed, whereby the affixes s for causative , m for passive and reflexive verbs and t for the medium can be found, see the following examples from Somali:

- for "open"> for-am "to be opened"

- for "open"> fur-at "open for yourself"

- cun "eat"> cun-sii "let eat"

literature

overview

- Gene B. Gragg: Cushitic languages . In: Burkhart Kienast: Historical Semitic Linguistics . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2001, pp. 574-617

- Hans-Jürgen Sasse: The Cushitic Languages . In: Bernd Heine, Thilo C. Schadeberg and Ekkehard Wolff: The languages of Africa. Buske, Hamburg 1981, pp. 189-215

- Mauro Tosco: Cushitic overview . In: Journal of Ethiopian Studies . tape 33 , no. 2 , 2000, pp. 87-121 .

- Andrzej Zaborski: The Verb in Cushitic. Krakow 1975

Internal and external classification

- David A. Appleyard: Beja as a Cushitic Language . In: Gábor Takács (Ed.): Egyptian and Semito-Hamitic (Afro-Asiatic) studies. In memoriam W. Vycichl . Brill, Leiden 2004, ISBN 90-04-13245-7 , pp. 175-194 .

- David A. Appleyard: Semitic-Cushitic / Omotic Relations. In: Stefan Weninger et al. (Ed.): The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. DeGruyter - Mouton, Berlin 2011, pp. 38–53.

- Robert Hetzron: The limits of cushitic . In: Language and History in Africa . tape 2 , 1980, p. 7-126 .

reconstruction

- David L. Appleyard: A comparative dictionary of the Agaw languages. Köppe, Cologne 2006. ISBN 3-89645-481-1

- Christopher Ehret: The historical reconstruction of Southern Cushitic phonology and vocabulary . Reimer, Berlin 1980, ISBN 3-496-00104-6

- Christopher Ehret: Proto-Cushitic Reconstruction. In: Language and History in Africa , Volume 8, 1987, pp. 7-180

- Christopher Ehret: Revising the Consonant Inventory of Proto-Eastern Cushitic . In: Studies in African Linguistics . tape 22 , no. 3 , 1991, pp. 211-275 .

- Roland Kießling and Maarten Mous: The Lexical Reconstruction of West-Rift Southern Cushitic (= Cushitic language studies . Volume 21 ). Köppe, Cologne 2003, ISBN 3-89645-068-9 .

- Hans-Jürgen Sasse: The Consonant Phonemes of Proto-East-Cushitic (PEC): A First Approximation. Afroasiatic Linguistics, Volume 7, Issue 1 (October 1979). Undena Publications, Malibu 1979 ISBN 0-89003-001-4

- Andrzej Zaborski: Insights into Proto-Cushitic Morphology . In: Hans G. Mukarovsky (Ed.): Proceedings of the Fifth International Hamito-Semitic Congress . tape 2 . AFRO-PUB, Vienna 1991, ISBN 3-85043-057-X , p. 75-81 .

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Robert Hetzron: The limits of cushitic . In: Language and History in Africa . tape 2 , 1980, p. 7-126 .

- ^ Richard Hayward: Afroasiatic. In: Bernd Heine, Derek Nurse (Ed.): African Languages. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2000, ISBN 0-521-66629-5 .; Rainer Voigt: On the structure of the Cushitic: The prefix conjugations . In: Catherine Griefenow-Mewis, Rainer M. Voigt (Eds.): Cushitic and Omotic languages: Proceedings of the Third International Symposium, Berlin, March 17-19, 1994 . Köppe, Cologne 1996, p. 101-131 .

- ↑ Christopher Ehret: Reconstructing Proto-Afroasiatic (Proto-Afrasian), Vowels, Tone, Consonants, and Vocabulary . University of California Press, Berkeley 1995, ISBN 0-520-09799-8 ( University of California Publications in Linguistics , Volume 126).

- ↑ Kießling and Mous 2003, Tosco 2000 (see bibliography)

- ↑ Graziano Sava, Mauro Tosco: The classification of Ongota language . In: Lionel Bender u. a. (Ed.): Selected comparative-historical Afrasian linguistic studies. LINCOM Europe, Munich 2003.