Second Italo-Libyan War

| date | January 26, 1922 to January 24, 1932 |

|---|---|

| location | Libya |

| exit | Italian victory, first full occupation of Libya by Italian troops. |

| conflict parties | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| commander | |

|

|

|

Second Italo-Libyan War (or Second Libyan-Italian War ) is a summary term for the wars of conquest waged by the first liberal and then fascist Kingdom of Italy against what it claimed as colonies in what is now Libya : Tripolitania and Cyrenaica . The conflict lasted almost ten years from January 26, 1922 to January 24, 1932.

The fighting began under Italy's liberal government in Tripolitania and continued from October 1922 by Benito Mussolini 's coalition government . In 1923, this extended the military actions to Cyrenaica. Some of the North African territories had already been occupied by Italy from 1911 to 1914, but largely slipped out of Italy's control during the course of the First World War . The reconquest of northern Tripolitania was completed in 1924, but the Italian troops were only able to subjugate Fessan to the south in 1930. Finally, until 1932, the resistance movement of Sheikh Omar Mukhtar in Cyrenaica was suppressed.

The liberal as well as the fascist campaigns pursued two goals: on the one hand the conquest of all claimed areas, on the other hand the conversion of Libya into a settlement colony for Italian immigrants. Accordingly, the Italian colonial power operated an expropriation and - after the enforcement of the fascist dictatorship in the mid-1920s - systematic expulsion of the Berber and Arab population from the fertile regions of the country. Some historians already see this in the context of the fascist idea of conquering new “living space” ( spazio vitale ) . Italy's warfare became increasingly brutal and used carpet bombing , poison gas and mass executions as military weapons in both contested areas. Most devastating was the genocide in Cyrenaica from 1929 to 1934 , which killed between a quarter and a third of the total population of Cyrenean in death marches , deportations and the first concentration camps set up by a fascist regime . In total, about 100,000 of the approximately 800,000 Libyans fell victim to the war.

In research, the Italian colonial war and genocide are considered evidence against the myth of a “moderate” Italian fascism and colonialism and as an important part of the history leading up to the Abyssinian War that began in 1935 . A possible model function of this Libya policy for later National Socialist settlement plans in Eastern Europe is also discussed . The failure to deal with the conflict strained diplomatic relations between Libya and Italy for decades. In 2008, both countries finally agreed on a friendship agreement in which Italy apologized for the colonial period and committed to financial compensation.

designation

In the literature, the term "reconquest" or "reconquest" (riconquista) of Libya is often used for the conflict. However, this designation is criticized by some historians because it reflects the fascist view of the events: The term riconquista has a certain basis in relation to Tripolitania, since it had already been occupied by Italian troops between 1913 and 1914 until Fezzan. However, the name is not appropriate for Cyrenaica, since its hinterland had previously always been under the control of the Senussi movement . We must therefore speak of a conquest here. Aram Mattioli (2005) therefore advises using the term “reconquest of Libya” sparingly and always in quotation marks. Other historians, on the other hand, continue to use the term reconquest for both areas. The colonial wars in Italy in the 1920s over the North African territories also went down in military history as the “pacification wars”.

In German-speaking history, the colonial war in Libya from 1922 to 1932 is also known as the "Second Italo-Libyan War" or "Second Libyan-Italian War", which is distinguished from the earlier First Italo-Libyan War of 1911 to 1917. In English-language historiography, "Second Italo-Sanussi War" is also common as an alternative name in relation to the war in Cyrenaica from 1923 to 1932. The Arabic name isإخماد الثورة الليبية/ iḫmād aṯ-ṯaura al-lībīya / 'Crushing the Libyan Revolution' orالحرب الإيطالية السنوسية الثانية/ al-ḥarb al-īṭālīya as-sanūsīya aṯ-ṯāniya / 'Second Italo-Senussi War'. The genocide committed by fascist Italy in Cyrenaica is described by the Libyans asالشر/ aš-Šarr (evil) denoted.

prehistory

Italian Colonialism and First Libyan War

Italian colonialism began in 1882 in East African Eritrea , after the first private acquisition of territory had already taken place in 1869. Under Prime Minister Francesco Crispi , it expanded into a colonial campaign against Eritrea and the Abyssinian Empire , which ended in 1896 with the victory of the Abyssinian army over Italian troops at the Battle of Adua . As a result of this defeat, the interest of Italian politics was increasingly directed towards today's Libya. This had been under Ottoman rule since 1551 as the province of "Tripolitania" and was now their last possession in North Africa. The local foundations for colonial conquest had been laid since the 1890s, when Italian banks, schools and newspapers began to flourish in the province , especially in Tripoli . In addition, trade relations were established with influential Jewish and Muslim traders. Eventually opened in 1907, the "Bank of Rome" gained a key position in the purchase of land, commercial investment and the recruitment of employees for the Italian cause. Italy 's imperialist strategy also included the revival of the historical term " Libya " to justify colonial claims by reference to the earlier rule of the Roman Empire in the region.

On September 28, 1911, the Kingdom of Italy , under Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti , asked the Ottoman Empire for a free hand in occupying Libya. Sultan Mehmed V rejected this ultimatum . The Italian-Turkish war over Libya began the next day with Italy's declaration of war , and on September 30 Italian troops began shelling the Tripoli fort. Based on the assumption that the Libyan population hated “Ottoman tyranny and backwardness”, the Italian leadership expected to be able to achieve a speedy occupation of the country with limited military operations. In reality, the Italians soon faced one of the strongest and most militant anti-colonial resistance movements in Africa. The Libyan population clung to the Ottoman sultan as their spiritual and political leader, so that the Ottomans and Libyans put up fierce resistance to the Italian expeditionary force. Even liberal Italy relied on excessive acts of violence: as a result of their defeat at Shar al-Shatt (Sciara Sciat) on October 23, 1911, the Italian invading army had thousands of Arabs shot and hanged. Still, Italy managed little more than conquering a few enclaves along the Mediterranean coast into the following year. In October 1912, with the Ottoman Empire weakened as a result of the First Balkan War and Italy becoming an increasing threat with the attack on the Dodecanese archipelago and the Dardanelles , the Ottomans and Italians concluded the Treaty of Ouchy . The unclear and ambiguous agreement led to the withdrawal of Ottoman troops from Libya, however, the Ottoman Empire did not completely relinquish its sovereignty over the North African country. Italy, on the other hand, insisted on its own claims to sovereignty. The final renunciation in favor of Italy was made by the Turks later in the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923.

On January 9, 1913, the new colonies "Italian Tripolitania" (Tripolitania italiana) and "Italian Cyrenaica" (Cirenaica italiana) were formed. Nevertheless, the resistance of the local population continued. In addition, even after the Ottoman army had officially withdrawn, a group of Turkish officers remained in the country and continued their fight against the Italians. The Italians succeeded in conquering North Tripolitania in 1913 and Fezzan in 1914 , also because Arabs and Berbers as well as the individual Arab tribes could not agree on a uniform resistance among themselves. In Cyrenaica, on the other hand, where the resistance was concentrated around the Islamic - Sufist Senussi Brotherhood (Sanusiya) of Ahmad al-Sharif , Italy's troops still did not get beyond the coastal strip. The beginning of the First World War required the transfer of large numbers of troops and reduced the forces of the Italian occupying power, whereupon a rebellion began in Fezzan in November 1914, which also spread to northern Tripolitania. The combined troops from North Tripolitania, Fessan and Cyrenaica managed to defeat the Italian army, after which it withdrew to the coast - in the summer of 1915 Italian rule was limited to the port cities of Tripoli , Derna , Homs and Benghazi . This situation, humiliating for Italy's great power ambitions, persisted until after the First World War.

State foundations in Cyrenaica and Tripolitania

The period from 1915 to 1922 is considered the second phase of colonization. Weakened by the entry into the world war and beset by the Libyan resistance, Italy had to make several concessions to the Arabs and Berbers from 1915 onwards. In addition, two indigenous states formed on Libyan soil during this phase, the Senussi Emirate in Cyrenaica and the Tripolitan Republic. As early as late 1912, the Senussi leader Ahmad al-Sharif moved his camp from southern Kufra to the more northern oasis of al-Jaghbub and proclaimed his independent emirate , based on the Arab tribes of Cyrenaica. During World War I, the Ottomans pushed the militantly pan-Islamic Senussi leader into attacks against British Egypt , discrediting al-Sharif with the British. In order to enable an anti-Italian alliance between Great Britain and the Senussi Emirate, he resigned in 1916 in favor of his cousin Idris as Senussi leader. This resulted in diplomatic de facto recognition by the British of the Senussi Brotherhood as the representative of Cyrenaica. In the same year, Idris opened negotiations with the Italians, mediated by Britain, which resulted in the Treaty of Acroma (Akramah) in April 1917. In it, Cyrenaica was divided into two spheres of interest, the Italian-dominated coastal strip and the entire remaining area under the administration of the Senussi. As early as 1915, however, the Italians had been promised rule over all of Libya in the Treaty of London by Great Britain, France and Russia. Nevertheless, in the Regima Accords on October 25, 1920, Italy recognized Idris' hereditary sovereign title of Emir over his territory with Ajdabiya as the administrative center. The Italians paid him and his family monthly allowances, shared his general expenses, and subsidized his army and police forces.

In Tripolitania, on the other hand, the retreat of the Italians from the interior of the country in 1914/1915 had led to a chaotic power vacuum that a number of rival tribal leaders tried to fill. It came to tribal wars and a splitting up into many small dominions. By 1916, two main fighting factions, the Senussi order active in the Syrte Desert, and Ramadan al-Shutaywi (also al-Suwayhili or al-Shitawi ) established themselves as rulers of north-eastern Tripolitania. As the Senussi attempted to expand their influence over the rest of Tripolitania, war ensued with al-Shutaywi, who defeated them in a battle at Bani Walid (Beni Ulid). As a result, the influence of the Senussi outside of Cyrenaica was reduced to parts of Fezzan.

After the Turks finally withdrew from Tripolitania in 1918, the tribes there found themselves without strong allies - in contrast to the British support for the Senussi order in Cyrenaica. Therefore, the tribal leaders agreed on an all-Tripolitan government and in November 1918 in Msallata (Al Qasabat) proclaimed the "Tripolitan Republic" with the capital Misrata - the first formally democratic government in an Arab country. The republic was founded on a pan-Islamic ideology and was administered collectively by four prominent tribal leaders - the so-called "Council of the Republic" - as the Tripolitan tribes could not agree on a leader. In addition, Egyptian pan -Arab nationalist Abdel Rahman Azzam served as government adviser. After the Senussi Emirate in Cyrenaica, the Tripolitan Republic became the second indigenous state on Libyan soil.

As early as 1917, Italy granted the Tripolitans self-government rights . In 1919 they succeeded in negotiating a peace treaty with the colonial authorities, which granted Tripolitania a parliament , freedom of the press and citizenship for the Muslim population. In the spring of 1920, the Tripolitan government tried to assert its authority over all tribes of Tripolitania with a military campaign, which again led to a civil war. This could only be settled in November 1920 with the Gharyan Accords , in which the old Council of the Republic was replaced by a reform committee as the new government. Any notions of Rome of Italian sovereignty over Tripolitania were rejected. Outside the coastal cities ruled by Italy, and sometimes even within them, the Reform Committee of the Tripolitan Republic issued edicts and collected taxes and other levies of its own. In addition, German and Turkish officers were smuggled into Tripolitania and helped set up the republican administration, train a small regular army and build a weapons and ammunition factory. However, since the Italians had already secured their colonial claims to Tripolitania in treaties with Great Britain and France, the new republic was not recognized by any other state. Unable to put up a strong front against the Italians, the leaders of Tripolitania also offered rulership of Tripolitania in December 1921 to the Senussi chief Idris, now recognized by the Italians as Emir of Cyrenaica.

course

Campaign of Liberal Italy (1922)

In response to the Tripolitanians' attempt to create an anti-Italian alliance with Cyrenaica led by the Senussi, Governor Giuseppe Volpi launched the campaign to retake Tripolitania on January 26, 1922. By sea, a 1,500-strong Italian force landed near the port of Misrata. The port, held by around 200 defenders, could only be taken by the Italians after seventeen days. Within a week of the fighting beginning, the Tripolitan Reform Committee called for an attack on all Italian posts and proclaimed jihad . The railway connection to Tripoli was interrupted and the Eritrean Askari unit of the Italians in al-ʿAzīzīya was besieged - many other smaller combat actions followed. After a government crisis in Rome and the appointment of the new Colonial Minister Giovanni Amendola , a ceasefire was agreed at the end of February because the leadership in Rome was still undecided about how to proceed.

Developments in neighboring Egypt, which declared its independence from Great Britain as a kingdom in March 1922, had a motivating effect on the Tripolitans . Since Tripolitania depended on the support of the Senussi leadership of Cyrenaica, Tripolitan envoys attended the gathering of Cyrenean tribal leaders in Ajdabiya, where they offered rulership of Tripolitania to Idris as-Senussi. On June 22, Idris was also officially proclaimed Emir by the Tripolitan representation, but did not accept the title until September 22. After the end of the armistice on April 10, 1922, Governor Volpi, now enjoying the full support of the Italian government in Rome, was ready for a "restoration of normalcy," as the pre-fascist term for the reconquest was. His 15,000 soldiers faced about 7,000 "rebels" who attacked the Italians at az-Zawiya . The young Colonel Rodolfo Graziani , whom Volpi had gathered around him together with other competent officers, now managed in ten days to occupy the coastal strip from Tripoli to Zuwara .

Graziani modernized the methods of desert warfare, relying on fast-moving formations of armored vehicles supported by air and unbridled brutality. Under the supervision of General Pietro Badoglio , a hero of the First World War who had just arrived in Tripoli, Graziani marched on April 30 into the city of al-ʿAzīzīya, which was besieged by the Tripolitan resistance. By mid-May, the Italians gained control of the plains of al-Jifara and inflicted heavy losses of 6,000 men on the Tripolitans. At the end of May, Graziani began the "pacification" of the western mountains of Jabal Nafusa, with the city of Nalut falling on June 5 . Governor Volpi, who was no longer willing to negotiate with the Tripolitan representatives, had meanwhile imposed martial law on Tripolitania, which corresponded to a formal declaration of war. Mussolini 's March on Rome in October 1922 initially had little effect on the war. On October 31, Graziani announced the capture of the city of Yafran , followed in November by the conquest of the mountainous region from Nalut to Gharyan .

Continuity and reorientation of colonial policy under Mussolini

Fascist Italy could already look back on a long colonial tradition from the previous liberal government. At the same time, under the Mussolini government, colonialism was transformed: similar to imperialist Japan , and in sharp contrast to traditional nineteenth-century colonialism, the fascist dictatorship sought to implement a form of settler -colonialism that was “totally controlled from above, and which provided for the resettlement of millions of colonists". Also, Italian colonial fascism was based to a much higher degree on racist ideology, and used unprecedented violence against the native population. When and to what extent Mussolini's assumption of office as Prime Minister ushered in a new (third) phase of the colonization of Libya is a matter of debate among historians. According to Hans Woller (2010), Mussolini's government immediately gave the campaign "a new quality after 1922", which was expressed above all in the large-scale expropriation of the local population. This pressure on the Libyans then increased after the establishment of the fascist dictatorship in 1925. Other historians place the beginning of the Fascist phase in 1923, when Italy also renounced the treaties of autonomy and self-government with the Senussi and began conquering Cyrenaica. The Italian historian Luigi Goglia (1988) cites April 15, 1926 as the key date for the change from liberal to fascist colonialism. On this day, Mussolini celebrated the previous conquests in Libya in Tripoli and gave a famous keynote speech on Italian colonial policy.

The fascists were not only concerned with subjugating the rebellious tribes. The aim of imperial policy was to provide the Italian people with the "living space" they needed to fulfill their "historical mission". From the fascist point of view, the "pacification of the country" was merely the basic requirement for the further development of the two North African territories. They considered the possession of colonies to be both necessary and legitimate, since an overpopulated nation without natural resources – such as Italy was from their point of view – had a “natural right” to seek compensation overseas. A thriving colony of settlements was to develop around the Great Syrte , based on the model of the ancient Roman Empire with its cities of Sabratha , Oea , Leptis Magna and Cyrene .

Mussolini first wanted to be the master of his own possessions and consolidate them before he could start further imperial actions from there. His plans envisaged the advance from North Africa through the Sahara via Cameroon to the Atlantic and from there a connection to the Horn of Africa , so that eventually the entire northern half of Africa would have been part of his empire. Italy was too weak militarily and economically and too dependent on international financial and commodity markets to openly challenge the Western powers . The new government's urge to expand was therefore initially directed towards its own colonies in North Africa (Tripolitania and Cyrenaica) and on the Horn of Africa ( Colony of Eritrea and Italian Somaliland ). According to the German historian Hans Woller (2010), the reconquest of the colonies cannot therefore be seen as an act of domestic politics, but "it formed the prelude to a gigantic program of conquest, in the realization of which Mussolini resorted to the most radical means possible". Under the slogan La Riconquista Fascista della Libia ("The Fascist Reconquest of Libya"), the government began a broad-based military offensive to subdue all parts of Libya. The aim of this military operation was, on the one hand, a complete "pacification" of the country and, on the other hand, the extensive expulsion of the local population in order to smooth the way for the colonization of Libya by Italian settlers.

"Reconquest" of North Tripolitania (1923–1924)

The Fascist government initially focused on conquering Tripolitania, which held four-fifths of the fertile soil. The general offensive there began on January 29, 1923, and already on February 5 the Italians took the city of Tarhuna . An advance via Zliten to Misrata followed , which was occupied on February 26, 1923. As a result, the Italian Air Force also bombed Arab refugee treks with over 2,000 people from Zliten. With the occupation of the hill country of Jabal Nafusa and the coastal city of Misrata in February 1923, the taking of so-called "useful Tripolitania" was complete. Difficulties initially arose when military action was extended to eastern and southern Tripolitania. However, conflicts between the Tripolitan tribal leaders over collaboration with the Senussi movement weakened the resistance: while Ahmad Sayf al-Nasr collaborated with the Senussi, other insurgency leaders such as Abbot al-Nabi Bilkhayr and Ramadan al-Shutaywi opposed the presence of the Senussi Senussi in Tripolitania. From the spring of 1923, the "reconquest" of Tripolitania became increasingly brutal towards the rebellious tribes. Some escaped to the Syrte Desert, some tribal leaders fled to Tunisia and Egypt . In December 1923 Bani Walid fell into Italian hands, in February 1924 Ghadames was conquered. With the capture of Mizda in May 1924, the "pacification" of North Tripolitania was complete. Rodolfo Graziani was promoted to general as the "hero" of the campaign.

At its core, the fascist policy of conquest aimed at a redistribution of arable land and the destruction of traditional tribal societies . Part of this program was the expulsion of the indigenous population, who now had to move from the fertile coastal regions to the dry areas if they did not want to work for the colonial power for starvation wages to build representative buildings and roads. Even under Governor Volpi, there was a wave of land expropriations that undermined Tripolitania's traditional economic and social system. In 1923, Volpi issued a decree that provided for the confiscation of all lands belonging to people supporting the Libyan resistance. As a rule, the country was not handed over to small colonists, but rather to agrarian societies, latifundists or deserving fascists. Governor Volpi alone was given two million hectares of land for his "merits" and thus became a large North African landowner before he was appointed finance minister in Mussolini's cabinet in the summer of 1925 . The Swiss historian Aram Mattioli summarizes this part of Italian colonial policy as "a gigantic land grab", as tens of thousands of hectares of fertile soil have changed hands every year since 1923. The southern region of Fessan now became the place of refuge for the majority of the Tripolitan tribes who offered resistance. Together with the Fesanian tribe of the Awlad Sulayman, they henceforth waged guerrilla warfare . They fought the Italians in small groups, avoiding pitched battles and engaging only in short skirmishes and skirmishes. Especially at night they committed acts of sabotage and attacked convoys and military stations.

Due to the slowly progressing expansion to the south, in July 1925 Mussolini appointed the 59-year-old General Emilio De Bono as Volpi's successor as Governor-General of Tripolitania. Under De Bono, a highly decorated World War II general and fascist leader at the March on Rome, the Italians reacted to the mujahideen 's guerrilla tactics with an increasingly brutal small-scale war: numerous executions and the use of poison gas ensued . Italy outnumbered the “God Warriors” both numerically and technologically.

Guerrilla warfare in Cyrenaica (1923–1927)

Senussi movement and Italian initial offensive

Unlike Tripolitania, where old rivalries and tribal conflicts had prevented the formation of a unified front of resistance, in Cyrenaica the insurgents were united. Here the resistance was based entirely on the Senussi movement, a brotherhood founded in Mecca in 1833 , which campaigned for the renewal of Islam and the liberation of Arab countries from European influence. The Senussi Brotherhood maintained a finely woven network of Islamic cultural centers and was thus socially anchored in Cyrenaica. These so-called "mixed camps" (zǎwiyas) were places of residence and gatherings that served both faith and important functions in social life. In addition to mosques and Koran schools, they often included hospitals, shops and accommodation for travelers and played an important role in trade and exchange. The zǎwiyas were led by sheikhs of the Senussi.

The Bedouins of Cyrenaica rejected any form of colonial heteronomy that threatened their traditional way of life as pastoral nomads. Islam and above all the orthodox Sufi teachings of the Senussi movement were the ideological and cultural basis of the resistance movement. The religious regulations of their founder Mohammed Ali as-Senussi (1787–1859) formed the core of an independent national culture from which the anti-colonial struggle drew its motivation and legitimacy. Since the flight of its emir Idris as-Senussi to Egypt (1922), the Senussi order has been under the deputy leadership of his brother Mohammad al-Rida. Idris handed supreme command of the military resistance to Omar Mukhtar , a Senussi sheikh in his 60s.

In early 1923, General Luigi Bongiovanni became the first fascist governor of Cyrenaica and received a personal “strike hard” order from Mussolini. In March, Bongiovanni demanded that Senussi deputy chief Mohammad al-Rida shut down the Islamic zǎwiya centers and other military installations. Al-Rida retorted that he had no negotiating powers, after which the Italians began the war by occupying southern areas of Benghazi that same month. The Cyrenean Parliament was also dissolved in March 1923. In April, Al-Rida's administrative center , Ajdabiyah , was taken and all agreements with the Senussi up to that point were annulled. For the offensive, Governor Bongiovanni had four Italian, five Eritrean, and two Libyan battalions at his disposal, with a total of up to 8,500 infantry. There were also smaller cavalry, mountain and engineer units. The Senussi could draw on about 2,000 regular soldiers in the zǎwiya centers and up to 4,000 irregular warriors among the tribes of the Jabal Akhdar mountains .

In 1923, the Italians focused only on "pacifying" the area between the coastal cities of Qaminis and Ajdabiyah. Between May and September, 800 nomads were killed in Italian surprise attacks with armored vehicles and motorized infantry on the resistance camps. About 12,000 sheep also died or were confiscated. Bongiovanni's offensive saw some early successes, but these were hardly decisive. This included the dissolution of local zǎwiya centers and the temporary occupation of Ajdabiya. In June, the Italian troops managed the first mass subjugation (about 20,000 people) in the mountainous region near Barke , at the same time they suffered a heavy defeat in the fight with the Mogarba tribe, native to the Syrte desert, in which they lost 13 officers, 40 Italian soldiers and 279 Askari lost.

In 1924, Omar Mukhtar established a unified military council as well as numerous adwar . These were combat units of the individual tribes, each with a few hundred men. Each tribe volunteered with a certain number of fighters, weapons and food. In the event of their death, the tribes promised to replace them. The desert warriors were far inferior to the Italian colonial troops in number, speed and firepower. They therefore avoided decisive battles and repeatedly dealt sensitive blows to the colonial power in small combat groups before retreating to their hiding places under cover of darkness. Over the years there have been hundreds of skirmishes and acts of sabotage. The holy warriors made up for their numerical and technological inferiority with their guerrilla tactics, their knowledge of the terrain and their social roots.

Battle for the Jabal Achdar and al-Jaghbub

The natural bulwark of the Jabal-Ahdar Mountains became the main area of the Cyrenean guerrillas from 1924. The limestone plateau in northern Cyrenaica, with its thickets and forests dotted with ravines and caves, presented ideal terrain for guerrilla warfare which they obviously acted more against the civilian population than against the adwar units of the resistance. Although the Italian armed forces killed hundreds of local men and tens of thousands of livestock, they were only able to secure a few dozen rifles. By 1924/1925 the Italians were at odds with most of the Cyrenean nomads. The residents of the towns and villages took little part in the fighting, but provided material support to the rebellion. The greatest resistance came from the people of the hill country, where there had been no central power since Roman times, and the desert dwellers, who had always ruled themselves. Altogether the tribes of Jabal Achdar lost 1,500 men and 90,000 to 100,000 domesticated animals between 1923 and 1926, according to Italian estimates, but still maintained control over most of the plateau and the semi-desert inland.

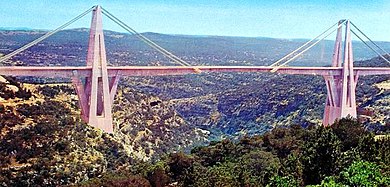

- The battlefield of Jabal Achdar

The current bridge over the Wadi al-Kuf (1970)

Ernesto Mombelli, who had succeeded Bongiovanni as governor in May 1924, now favored the conquest of al-Dschaghbub , the ancient capital of the Senussi order. By taking them, Mombelli thought he was undermining the prestige of the Senussi and perhaps bringing an end to the rebellion. An attack on al-Jaghbub had been contemplated several times since colonization began in 1911, but it was not until 1925 that Egypt recognized the city and an adjacent strip of territory as Italian territory. In January 1926, a motorized column of 2,500 men started its march against the small-walled city. On February 5, Italian airmen dropped leaflets on al-Jaghbub calling on residents to surrender and promising respect for the Senussi sacred site. Two Italian columns then cautiously entered the city without encountering any resistance. On February 7th the city was taken. The operation was a logistical triumph and demonstrated the Italians' increasing mastery of desert warfare, as 2,500 men had to be supplied across some 200 kilometers of desert. However, the victory had little effect on the course of the war. The Senussi fighters had left the place in time and their resistance remained unbroken.

The failure of the Italian military offensives in Cyrenaica stood in stark contrast to the concurrent successes that Italy was able to achieve in the campaign in Tripolitania. Therefore Mombelli was ordered back to Rome at the end of 1926 and replaced by General Attilio Teruzzi. Teruzzi - a high-ranking member of the fascist state party PNF - promised on arrival in Cyrenaica to enforce the "full power of Roman law" over the resistance fighters. General Ottorino Mezzetti, who was one of the commanders-in-chief in Tripolitania along with Rodolfo Graziani, was assigned to support him. The first objective of the two was to gain control of the Jabal Achdar. A large force was made available for this purpose: nine Eritrean and two Libyan Askari battalions, a Libyan cavalry squadron (Spahies) and other units - a total of about 10,000 men, to which were added local occupation forces consisting of Italian soldiers. The troops could also be coordinated more effectively through greater use of radio and air force.

The adwar troops were only able to counter this superiority with around 1,850 fighters. While the Italian armed forces only suffered minor losses in the fighting from July to September 1927, a total of 1,200 dead men and 250 women and children were taken hostage on the Cyrenean side. There were also thousands of livestock killed or confiscated by the Italians. The fact that the Italians were again able to confiscate comparatively few weapons (269 rifles) repeatedly indicates that the non-combatant population was more affected and that the majority of the rebels escaped. Nevertheless, the offensive marked a military turning point: the adwar units had to reduce their battle groups and avoid larger concentrations of troops. However, their support from the population remained unbroken.

Conquest of Fezzan (1928–1930)

As military governor for southern Tripolitania from 1926 to 1927, General Graziani concentrated on strengthening relations with individual tribes. Using a strategy of divide et impera , he sought to have individual tribal leaders collaborate with the Italians in order to gain them as an instrument for further advances south. The Berbers and some Arab tribes became Italian allies. The tribes of Awlad Sulayman, Warfalla , Guededfa , Zintan, Awlad Busayf and later also the Mashashiya offered resistance .

From the autumn of 1927, the Italian army was preparing to establish a land connection between Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, which was to be achieved by conquering all southern territories up to the 29th parallel. On the one hand, this was intended to eliminate the danger posed by the rebellious tribes of the Mogarba and the Awlad Sulaiman from the Syrte desert. On the other hand, General Graziani intends to drive a wedge between the Fesanian and Cyrenean resistance groups in order to have a clear back for conquest of southern Fessan. On January 1, 1928, his Tripolitan column started 50 kilometers west of Syrte, while the Cyrenean column marched from Ajdabiyah. Both units met on the Mediterranean coast at the village of Ras Lanuf . The Libyan resistance fighters withdrew, avoiding direct confrontation. The offensive achieved its first success on the second day, when Mohammad al-Rida, who was coordinating the resistance from his headquarters in Jalu, offered his unconditional submission to the Italians in Ajdabiyah. After al-Rida's surrender, his position as deputy head of the Senussi passed to Omar Mukhtar.

At the beginning of February, the Fesanian oasis of al-Jufra and the two Cyrenean oases of Jalu (Yalu) and Audjila were occupied by Italian troops. By March 1928 the coast and oases had been conquered by the Italians. The Arab resistance was defeated in two battles, in January at Bu Ella in Cyrenaica and in February north of the oasis of Zalla at Tagrift (Bir Tigrift) in Tripolitania. Here, on February 25, a seven-hour battle broke out between Italian forces and around 1,500 tribal warriors. The defenders finally had to admit defeat after 250 men were killed and hundreds wounded. The Italian Air Force played a key role in these operations. By the fall of 1928, the Italians were able to gain some control over the conquered territories, but their rule was still uncertain. Thus, between October 29 and 31, 1928, a resistance group attacked the Italian forces at the oasis al-Jufra, with the Arabs withdrawing to their base in Fezzan after heavy fighting and about a hundred dead.

The conquest of Fessan now proceeded in three phases and began at the end of November 1929: The first Italian objective was the capture of the valley of Wadi al-Shati' , where the settlements of the rebellious Zintan tribe were located. After that, the Italians advanced to Wadi al-Adzhal - here the warriors of the Warfalla tribe gathered. The last phase was the Italian occupation of Murzuk, where the Libyan resistance was led by Ahmad Sajf an-Nasr. On December 5, the city of Brak fell into Italian hands, nine days later Sabha followed, and in mid-January 1930 the Italians captured Murzuk. Finally, on February 15, 1930, the Italian tricolor was hoisted over the occupied Ghat. The remnant of the defeated tribes fled towards Tunisia, Niger , Chad or Egypt, General Graziani having them bombed by the Italian Air Force along the way.

warfare and war crimes

Three quarters of the Italian units, commanded by battle-hardened officers, consisted – in addition to soldiers from Italy – of Eritrean Askaris, who were feared for their particular cruelty. The vast majority of them were Christians who had been mobilized to fight the Libyan Muslims. The Arabs named them Massuā after the Eritrean port city of Massawa . Altogether, Eritrea, as Italy's first colony, provided between 60,000 and 150,000 colonial soldiers for the conquest and occupation of Libya between 1911 and 1943. At the same time, around 1929, the Italian colonial power had also found collaborators among the Libyans who served as military tour guides, security guards, spies, advisers or soldiers. These collaborators were referred to by the Libyan resistance as banda (Italian for military bands ) or mutalinin ('the ones who became Italian').

Like the other colonial powers, Italy also used the most modern warfare techniques. These include telephone and radio to coordinate the actions; fast, lightly armored units and, above all, aircraft, which the mounted or foot-fighting Mujahideen had no equivalent to counter. For the Regia Aeronautica , the Italian Air Force, which had only existed as an independent branch alongside the Army and Navy since 1923, the colonial campaign of conquest in North Africa developed into the first emergency ever. In addition to reconnaissance and supply tasks, it naturally also intervened in combat operations. Not only fighters, but also the camps of the tribes were bombed by it or taken under automatic fire. The low-flying aircraft did not spare the treks of refugees with their cattle trying to make their way to Egypt or Algeria. The Italian Air Force also used carpet bombing , the so-called "flying courts".

Like Spain in the Rif War in Morocco, the Italian Air Force used poison gas in Libya, albeit sporadically . The main proponent of this type of warfare was the fascist governor Emilio De Bono; the warfare agents used were yperite and phosgene . It is estimated that between 1922 and 1930 a total of 50 chemical-filled bombs of various calibers were dropped in Libya. According to rough estimates, at least a hundred men and women and around 2,000 animals fell victim to these attacks. In 1925, for example, the Tripolitan tribe of the Zintan was bombed with poison gas at their main camp in al-Tabunia. In January 1928, four Caproni Ca.73 aircraft dropped poison gas bombs on around 400 tents south of Nufilia, and in February 1928 the Fesanian tribe of the Mogarba er Raedat was covered with yperite. On July 31, 1930, the Italian Air Force bombed the Cyrenaica oasis of Tazerbo , where "rebels" were suspected, with 24 Yperite bombs, each weighing 21 kilograms. In Cyrenaica, Kufra, the "sacred city" of the Senussi, was also a target of poison gas attacks. With these actions, Mussolini and his generals violated the 1925 Geneva Protocol prohibiting the use of asphyxiating, poisonous or similar gases, to which Italy was unreservedly co-signatory.

Conventional repressive measures such as arbitrary mass shootings and public executions claimed far more lives than the use of poison gas. Their purpose was to discourage civilians from collaborating with the resistance groups. There are hardly any archives available today about these massacres and the countless death sentences that were pronounced and carried out by military tribunals, which makes it very difficult to reconstruct the events. The destruction of villages and the annihilation of livestock as a means of war against the Libyan civilian population has only been documented in writing in isolated cases.

Reorganization of the colonial administration (1928–1929)

In December 1928, Mussolini personally took over the colonial ministry and on December 18 appointed Marshal Pietro Badoglio as the first joint governor general of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, which remained administratively independent until 1934. Badoglio took up his new post on January 24, 1929. Instead, Emilio De Bono first became Mussolini's undersecretary of state and in September 1929 himself the new colonial minister, with Mussolini continuing to participate in all major decisions concerning Cyrenaica. In contrast to De Bono, Badoglio was not a veteran fascist, but a national conservative loyal to the royal family. Nevertheless, it was precisely under him that Italian warfare took on a genocidal dimension.

Genocide in Cyrenaica (1929–1934)

Faced with dual pressure from the Cyrenean Senussi fighters and the expectations of the Italian government, Badoglio resorted to a dual strategy of threats and negotiations. On the one hand, Badoglio proclaimed in his first proclamation of February 9, 1929: “No rebel will have peace anymore, neither he nor his family, neither his flocks nor his heirs. I will destroy everything, people and things.” With this declaration of war, genocidal warfare became vaguely apparent for the first time, since it was not only aimed at the resistance fighters, but also threatened penalties for their relatives and even their cattle for the first time according to the principle of collective guilt . On the other hand, Badoglio initially relied on an appeasement policy – against the repressive tendencies of previous years. In the proclamation, Badoglio promised a full pardon for anyone who submitted to the following three conditions: surrender their arms, respect the law and sever contact with the mujahideen. In June 1929, a two-month truce was agreed between Italy and the rebels. However, this policy of appeasement remained purely formal and served to shift the responsibility for further suffering of the population onto the rebels. After the negotiations had not led to the disarmament of the population and the dissolution of the adwar combat units by August , they were broken off by the Italians.

Focus of repression on the non-combatant population

After the failed negotiations with Omar Mukhtar, the Italian occupying power renewed its repressive policy towards the Cyrenian resistance in November 1929 with arrests and shootings. Since Badoglio had not been able to get the guerrillas in Cyrenaica under control by 1930, Mussolini appointed General Rodolfo Graziani as the new vice-governor of Cyrenaica at the suggestion of Colonial Minister De Bono. Graziani, notorious for his fascist firmness in principle, had just completed the conquest of Fezzan and made a name for himself as a “butcher” in the years of guerrilla warfare among the Libyans. Interpreting the regime's slogans literally, he understood the pacification of the country as a subjugation of "barbarians" by "Romans". On March 27, 1930, Graziani moved into Benghazi 's governor's palace . Colonial Minister De Bono regarded an escalation of violence as inevitable for the "pacification" of the region and suggested the establishment of concentration camps (campi di concentramento) for the first time in a telegram to Badoglio on January 10, 1930 . Badoglio had also come to the conclusion that the "rebels" could not be permanently subjugated with the counter-guerrilla methods used up to now. From now on, both appeared in the framework of action defined by Mussolini as masterminds and strategists of genocidal warfare, while Graziani fulfilled the role of the executor.

The Italians originally divided the Libyan population into two groups, the armed resisting "rebels" and the non-combatant, subjugated population (sottomessi) who, in the eyes of the colonial administration, had capitulated. They wanted to undermine the unity of the people and act more efficiently against the armed fighters. Now, after the failure of the military offensive against the resistance movement, the Italians changed their minds. It became clear that a clear distinction between the two groups was not possible, since the resistance movement was supported materially and morally by the "subdued population". The civilians paid taxes, donated weapons, clothing or food to Omar Mukhtar's desert warriors or provided them with horses. Since the non-combatants thus ensured the reproductive conditions of the adwar system and formed the social basis of the resistance movement, they were now classified as dangerous potential by the colonial administration.

During the spring and summer of 1930, Graziani systematically targeted the social environment of the guerrillas. As a first measure, he had the Islamic cultural centers (zâwiyas) closed. Their superior Koran scholars were captured and deported to the Italian prison island of Ustica . Their lands were expropriated; hundreds of houses and 70,000 hectares of prime land, including the cattle on them, changed hands. In addition, Graziani ordered the complete disarmament of non-combatants and draconian penalties for civilians collaborating with Omar Mukhtar 's adwar combat groups. Anyone who owned a weapon or provided support to the Senussi order faced execution. In the colonial administration, Graziani began a purge of Arab employees accused of treason. He had the battalions of Libyan colonial troops, which had often indirectly supported Omar Mukhtar's resistance in the past, dissolved. All forms of trade with Egypt were banned in order to control the smuggling of goods to the insurgents. Last but not least, Graziani began to develop a road network in the Jabal-Akhdar Mountains - a project not previously realized by any of his predecessors. Simultaneously with these measures, the Cyrenean population began a mass flight to the surrounding countries.

In order to smash Omar Mukhtar's adwar units, General Graziani decided to reorganize the troops under his command. In the summer of 1930 he had 13,000 men (1,000 officers, 3,000 Italian soldiers and 9,000 Askaris) at his disposal, which he now divided into eight Eritrean battalions, three squadrons with armored vehicles, a special transport company with trucks, two Saharan groups, four Libyan cavalry squadron and two mobile units of artillery . In addition, he had a legion of fascist militia , an occupation duties battalion, a motorized unit with 500 vehicles and up to 35 reconnaissance aircraft and light bombers. From June 16, 1930, Graziani tried to encircle and destroy Omar Mukhtar's units in a carefully prepared and coordinated operation with ten columns of different composition. However , the Senussi adwar combat units were once again informed in good time by the local population and by deserters from Italian colonial troops. By dividing into smaller groups, they were able to escape the Italian columns with slight losses.

death marches and deportations

At this point, Badoglio again took the initiative and strongly proposed a new dimension of repressive measures: by deporting the people of the Jabal-Akhdar Mountains, he wanted to literally create an empty space around the adwar combat units . On June 20, 1930, he stated in a letter to Graziani:

“First of all, it is necessary to create a wide and precise territorial separation between the rebel formations and the subjugated population. I am aware of the scope and gravity of this measure, which must lead to the annihilation of the so-called subject population. But now the way has been shown to us and we must go it to the end, even if the entire population of Cyrenaica should perish in the process.”

After a discussion with Graziani, Marshal Badoglio ordered the total evacuation of Jabal Akhdar on June 25, 1930. Three days later, the Italian army, together with Eritrean colonial troops and Libyan collaborators, began rounding up the population and their livestock. Italian archive documents date the start of the action to summer 1930. However, the vast majority of Libyan contemporary witnesses agree that the first such arrests had already taken place in autumn 1929. Specifically, Badolgio's order amounted to the forced displacement of 100,000 to 110,000 people and their internment in concentration camps - about half of the total population of Cyrenaica. While only an account of the deportation of a single tribe is available in Italian archives, the oral history of the victims gives a detailed account of the extent of the action, which covered the entire area from the Marmarica region on the Egyptian borders in the east to the Syrte Desert in the West concerned. However, the urban population on the coast and residents of the inland oases were not affected. From the assembly points, those who had been herded together had to set off in columns on foot or by camel; some were also deported from the coast by ship. Such deportation had few precedents in Africa's colonial history and eclipsed even Graziani's rabid counter-guerrilla methods.

Guarded primarily by Eritrean colonial troops, the entire population, along with their belongings and livestock, was forced on death marches that sometimes stretched hundreds of kilometers for 20 weeks. Anyone caught on the Jabal Akhdar after the forced evacuation faced immediate execution. In the summer heat, a significant number of the deportees did not survive the hardships of the marches, especially children and the elderly. Anyone who fell to the ground exhausted and unable to go any further was shot by the guards. The high death rate was an intended result of the marches, and the land that was freed was again in the hands of the colonists. Of the 600,000 camels, horses, sheep, goats and cattle that were taken along, only about 100,000 arrived. The survivors refer to the deportation as al-Rihlan ('path of tears') in Arabic.

concentration camp

The destination of the deportations was the Syrte Desert, the hinterland along the east bank of the Great Syrte . The climate there was harsh, with little natural protection from the sun and little water. The Italian occupying power had set up 16 concentration camps here for 13 million lire within a few months, in which around 90,000 prisoners were interned in tents. About 70% of the deported people were interned in the five major "penal camps" Agaila (Agheila), Braiga (Marsa el-Brega), Magrun (Magroon), Soluch (Slug) and Swani al-Tariya (Suani el-Terria), with camp Agaila is considered the most notorious among them. It served primarily to detain and "punish" family members of resistance fighters under the command of Omar Mukhtar. The camp guards consisted of Eritrean and Libyan colonial troops (Askaris).

The concentration camps were surrounded by double barbed wire fences and were organized as tent cities with hundreds of densely populated quarters. They were equipped with latrines, wells and a Carabinieri surveillance department, but they had no health service (in 1931 two doctors were in charge of a total of 60,000 prisoners in four camps) and food shortages prevailed. The camp inmates had to secure their survival mainly with their few provisions and their wages as underpaid forced labourers . Their livestock-based livelihood was all but wiped out because the concentration camps did not have adequate water and grazing land. The Italian authorities intervened only makeshiftly with rationed meals, which is why starvation and disease claimed tens of thousands of victims. According to survivor accounts, the inmates also ate grass, mice, insects, or scavenged animal droppings for grains to stay alive. General Graziani pointed out in 1930: "The government is calmly determined to starve people to the most miserable death if they do not obey orders completely."

With no money for clothing, thousands of inmates were forced to spend three years without shoes and in the same clothes they wore when they arrived at the concentration camps. Because many of the inmates could not wash once while incarcerated, fleas and infections were rampant, leaving inmates vulnerable to smallpox , typhoid , and blindness . In addition to malnutrition and epidemics, the inmates of the concentration camps were also exposed to violence, heat and extreme heteronomy. The able-bodied men and boys were obligated to work as forced laborers to build roads, buildings and wells. There were also regular rapes of women and public executions after failed escape attempts. Sterilizations were also carried out on the prisoners to a limited extent . The orphans of the internees were drafted into the Italian army and later used as colonial troops in the Abyssinian War.

The inmates were not released from the camps until late 1933 and early 1934, as the colonial power needed cheap labor for infrastructure work in the Jabal-Akhdar Mountains that would serve the military and future colonization by Italian settlers. Under the strict control of the colonial police, the camp survivors were resettled in the poorest part of their traditional tribal area. Unable to establish a decent livelihood, the men were forced to work in road construction, where their salary was a third less than that of Italian workers. Meanwhile, their sons were educated in the "boys' camps" (campi ragazzi) for future assignments as colonial soldiers in the Italian army.

Crushing the Resistance Movement (1931–1932)

The fascists managed to completely isolate the freedom fighters socially and economically by internment of the population in the concentration camps. As a result, the resistance movement was deprived of its social basis, weapons, money and food were missing and the adwar system collapsed. The Italian armed forces had thus created the conditions for smashing the resistance. Now Badoglio and Graziani decided to take the last independent bastion of the Senussi in Libya, the Kufra oases , 800 kilometers deep in the desert . Their conquest was not so much a military necessity, but primarily served prestige. The approximately 600 defenders of Kufra relied on their location, cut off from the outside world by the sandy desert, which had previously made them inaccessible to the Italian army. A few hundred resistance fighters who had fled Tripolitania and Fessan also gathered here under the Senussi flag. For the Italians, as in the campaigns against the city of Jaghbub (Jaghbub) and Fezzan, the logistics represented a greater enemy than the defenders, but they now dominated the desert with their technical and organizational superiority.

The Italian offensive against Kufra began in July 1930 with air raids lasting over four months. In December, the main column led by Graziani set out from Ajdabiyah, which had over 3,000 men - half of them on camels - and 300 motorized vehicles. In January 1931, the main units joined up with other motorized columns from Zalla and Waw al-Kabir outside of Kufra. Graziani monitored the advance from the air. On January 19, the defenders were defeated by Italian troops 20 kilometers from Kufra near the village of al-Hawari and suffered a complete defeat as a result of the Italian occupation of al-Tag (al-Taj) on January 20. The population of the Kufra oases reacted in panic to the events: a mass exodus to Egypt, the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan or the southern Tibesti mountains began. The fleeing residents were bombed by the Italian air force without military necessity. Others died in the desert of thirst , starvation, or exhaustion.

The occupation of Kufra extended Italian control to the southern frontier of Cyrenaica. In the northern Jabal-Akhdar mountains, armed resistance under Omar Mukhtar continued, while the non-combatant, subjugated population – destitute and frightened – recoiled from the Italian reign of terror. In order to finally break the resistance, Deputy Governor Graziani, in consultation with Badoglio and De Bono, had the Libyan border fence built along the border with the Kingdom of Egypt . It was a 270 to 300 km long and four meter wide barbed wire enclosure with fortified checkpoints. As early as the late 1920s, the resistance movement began smuggling much-needed weapons and food from Egypt to Libya. From April to September 1931, 2,500 locals built this border fortification, the so-called "Fascist Limes ". Monitored by aircraft and motorized patrols, this stretched from Bardia on the Mediterranean far into the Libyan desert. Such border fortifications were previously unknown in Africa. It cut off cross-border trade and fighter infiltration, cut off supplies of ammunition and weapons to the insurgents, and blocked their escape routes. This finally destroyed the possibility of continuing the resistance.

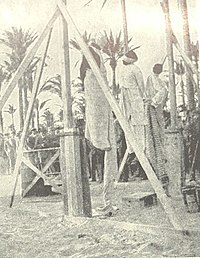

Gradually, Italy's genocidal warfare dealt blows to the resistance from which it never recovered. He was decisively hit in September 1931. During a skirmish, Omar Mukhtar's horse stumbled and threw the 70-year-old guerrilla leader off. An Italian unit managed to capture the injured. The guerrilla leader was chained and taken to Benghazi aboard the destroyer Orsini . There, a summary military court sentenced him to death by hanging in a show trial. Governor-General Badoglio had demanded the death penalty from the judges for high treason . On September 16, 1931, Omar Mukhtar was executed as a "bandit" in Soluch concentration camp in front of 20,000 prisoners. The death sentence had a dubious legal basis as, according to some lawyers, the leader of the Senussi fighters should have been treated as a prisoner of war. Even France, also known for its repressive colonial policy, refrained from executing celebrated insurgent leaders such as Abd el-Kader in Algeria or Abd al-Karim in Morocco. The fascist leadership's insistence on their "act of revenge" made seventy-year-old Omar Mukhtar a martyr for Arab independence and the Islamic faith. However, the already weakened guerrilla never recovered from this blow. Struck to the core by the loss of its charismatic leader, the resistance collapsed within weeks. On January 24, 1932, Governor General Badoglio reported to Rome that the overseas territory was completely occupied and "pacified" for the first time in over 20 years. The war was officially over with that.

Follow

casualty numbers

Estimates of the exact number of casualties in the Second Italo-Libyan War vary considerably. After taking power, the Gaddafi regime routinely said that half of the entire Libyan population perished during Italian colonialism; Gaddafi himself once mentioned up to 750,000 Libyans killed. Critical historiography rejects this information as exaggerated. Angelo Del Boca (2005) estimates that from 1922 to 1932 at least 100,000 of the approximately 800,000 Libyans fell victim to the war. Aram Mattioli (2005) and Hans Woller (2010) give the same figures for victims and the total population. However, Mattioli focuses on the period from 1923 to 1933, while Woller refers to the entire conquest process from 1911 to 1932. According to Del Boca (2005), the Libyan mine victims during the Second World War must also be added to these figures. Dirk Vandevalle (2012) and Ali Abdullatif Ahmida (2006) give casualty figures for the entire colonial period up to 1943. Vandevalle estimates that 250,000 to 300,000 Libyans died, mostly during the fascist era, out of a total population of 800,000 to 1,000,000. Ahmida cites 500,000 Libyans killed, but puts the total population at 1.5 million, significantly higher. According to the official account, the Italian troops lost 2,582 men.

An exact number of victims of the genocide cannot be determined because the Italian archives keep only a few documents about the death marches or concentration camps. In any case, the deportations to the camps and the living conditions there claimed far more victims among the Cyrenean population than the fighting between the Italian military and the resistance fighters. In the 1920s, the various tribes of Cyrenaica numbered around 225,000 people. In the 1931 census, that number dropped abruptly by 83,000 to just 142,000, and remained at that level until the 1936 census, which showed 142,500 people. The population of Tripolitania increased from 512,000 to 600,000 in the same period.

Part of the Cyrenean population loss can be attributed to the approximately 20,000 people who fled to Egypt in 1930/1931. Historians agree that at least 40,000 people died in the Italian camps from starvation, disease, shootings and hangings . Based on the previous death marches and deportations to the camps, estimates put the number of dead between 10,000 and 15,000. The maximum estimates of the total victims of the genocide are between 60,000 and 70,000 dead. Thus, within a few years, a quarter to a third of the total population of Cyrenaica had perished through forced resettlement and camp imprisonment, adding to that the 6,500 Senussi fighters who, according to Italian records, were killed in field battles between 1923 and 1931.

The herds, the economic basis of the semi-nomadic population, shrank continuously in the course of the colonial conquest. An Ottoman census from 1910, before the start of the Italian invasion, put Cyrenaica at 1,260,000 sheep and goats, 83,300 camels, 27,000 horses and 23,600 cattle. During Italian military operations from 1923 to 1928, an estimated 170,000 livestock were killed or confiscated as booty by the colonial power; however, livestock numbers for 1928 are still estimated at around one million. During their mass deportation in 1930, the residents of the Jabal Akhdar who were forcibly resettled were able to take around 600,000 farm animals with them. There is only incomplete, approximate and sometimes contradictory information on the systematic destruction of livestock that followed. Nevertheless, the following approximate values can be determined, which show a decline in sheep, goats and horses by 90-95% and losses of up to 80% in cattle and camels. Only after the completed "pacification" of Libya in 1932 did the Italian authorities deal with the partial restoration of the Cyrenian livestock.

| 1910 | 1926/1928 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sheep and goats | 1,260,000 | 800,000-1,100,000 | 270,000 | 67,000 | 105,000 | 123,000-222,000 |

| camels | 83,000 | 40,000-75,000 | 39,000 | 16,000 | 11,000 | 2,600-11,500 |

| horses | 27,000 | 14,000 | k. A | k. A | k. A | 1,000 |

| Bovine | 24,000 | 10,000-15,000 | 4,700 | 1,800 | 2,000 | 3,000-8,700 |

Libya under fascist rule

Under Fascist administration, Libya was less an African colony and more a colony of Europeans in Africa, where Italian immigrants received state assistance in appropriating and managing land: a settlement colony . The domination of the mother country primarily served the interests of these settlers. The mass extinctions in North Africa met the ultimate goal of the fascist colonization process, which was to gain new spazio vitale (“ living space ”). By 1939, around 100,000 Italian settlers had settled in Libya, which was almost exactly the number of casualties that the establishment of the colonial regime had cost the local population. The settlement plan provided for a total of 500,000 Italians to settle in the terra promessa (the "promised land") by the middle of the 20th century.

The Libyan possessions were to become a piece of Italy in North Africa: Libya's colony status was abolished in 1939 and the four northern provinces, excluding the Sahara region, were fully incorporated into the Kingdom of Italy. Since the cultivable soil played a central role in colonization, its confiscation was a priority. With land confiscation, local people were driven into barren areas unsuitable for agriculture, leading to the destruction of Libya's centuries-old socio-economic system.

This released masses of workers who either worked for the Italian settlers at starvation wages or were used by the colonial administration to expand the infrastructure. The extensive construction measures as part of the mass immigration included the construction of roads, houses, the approx. 310 km long railway and the ports of Tripoli, Benghazi, Darna and Tobruk, as well as the improvement of the soil. For these works, the Libyan labor force was a major force in the late 1930s. Thus, a socio-economic change took place, namely the formation of the Libyan workforce , albeit at an early stage. However, the expansion of infrastructure and agricultural development only benefited the Italian settlers. Unlike those in neighboring Egypt, Algeria and Tunisia, Libya's colonial economy did not create a native wealthy class. In the school system, the Italian colonial administration focused on state primary schools and the development of private Koran schools (katatib) , while opportunities for Libyans to attend secondary school and higher education were restricted. In 1939 there were only two Arabic secondary schools in Tripoli for the whole of Tripolitania, and only one secondary school in Benghazi in Cyrenaica.

In addition, the policy of racial segregation applied equally to rural areas and cities , with which Italian settler-colonialism manifested itself in an apartheid system from 1938 onwards. Since the 1920s, the fascist regime had gradually restricted the freedoms of the Libyan people. The right to free practice in Italy and the legal equality of Italians and Libyans in the colony itself were suspended, as were freedom of the press and freedom of expression. The originally privileged position of the Libyans compared to the inhabitants of the Italian colonies in East Africa, which the fascists had justified with a higher level of civilization, was increasingly equalized in the late 1930s. The 1938 Racial Laws classified "interracial marriages" between Italians and Africans as "damaging the Italian race" and prohibited them; in the following year, the second colonial racial law extended this ban to “marriage-like relationships” and supplemented it with numerous other provisions. Thus Libyans could only hold positions in military and civil administration where they were unable to command an Italian. The right to be elected mayor of a municipality only existed as long as there were no Italians resident in that municipality.

During the Second World War , after being briefly liberated by British troops as part of the North Africa campaign of 1940/41, the Libyan population dared to revolt several times against the hated Italian colonial power. The Italians responded with brutal repression, as a result of which it is estimated that several thousand Arabs, Berbers and Jews were killed. After the German-Italian troops surrendered in the Tunisian campaign , Libya was placed under British and French military administration in May 1943. In 1951 it became independent as the Kingdom of Libya and the first Saharan state.

Negotiations for reparations and war criminals

As a result of its independence in 1951, the issue of war damage and expropriations arose in the Kingdom of Libya, and the Libyan government asked Italy for equivalent compensation. The Italian government, on the other hand, took the position during the 1953-55 negotiations that it could not be held responsible for war damage in Libya during World War II because Libya had been an integral part of the Italian state during that time. The damage caused during the colonial occupation of Libya was not discussed because no other former European colonial power had made payments of this magnitude. Eventually, in October 1956, the very modest sum of 2.75 billion Libyan pounds, or 4.8 billion Italian lire , was settled . At Italy's request, the text of the agreement made no mention of the damage caused during the World War or during the colonial period; the funds flowed under the heading "Contributions to the economic recovery of Libya". With this formulation, democratic Italy tried to distance itself from the crimes of the colonial era, but precisely this unspecific wording made renewed Libyan demands for reparations possible .

The Kingdom of Libya also demanded the extradition of Generals Pietro Badoglio and Rodolfo Graziani . This was ignored by Italy - with the consent of the US and Britain - and not a single Italian accused of war crimes was ever extradited. Pietro Badoglio became Prime Minister of Italy after Mussolini was overthrown in 1943 and negotiated an armistice with the Allies, who in return prevented his prosecution. Rodolfo Graziani was tried after World War II, not for the mass murders in Libya and Ethiopia, but for his collaboration with Nazi Germany as defense minister of the fascist puppet state of Salò between 1943 and 1945. He was sentenced to 19 years in prison , but released again after four months. After his pardon, Graziani defended his actions and crimes in three books and became involved in the neo-fascist Movimento Sociale Italiano . For Graziani's 130th birthday in 2012, a memorial including a museum was erected in Affile , where he spent his final years.

While the Allies settled accounts with the regimes of Germany and Japan in numerous lawsuits after 1945, Italy's war crimes went unpunished. The Republic of Italy has shown little willingness to cooperate, particularly in the criminal prosecution of former military leaders. After the amnesty decreed by the communist Minister of Justice Palmiro Togliatti on June 22, 1946, the Italian governments did everything they could to prevent trials of their own war criminals – whether in Abyssinia, Libya or the Balkans. The impression was to be given that the Italian army itself, as an ally of Nazi Germany, was waging a clean war and was not guilty of anything in the occupied territories. The first post-war governments also showed no willingness to relinquish claims to the colonies. For years the coalition of the Christian Democratic head of government , Alcide De Gasperi , hoped to at least get back the pre-fascist overseas possessions. Significantly, the Africa Ministry in Rome continued to exist until 1953, although the Treaty of Paris in 1946 had officially drawn a line under Italy's 60-year colonial rule.

Italian-Libyan relations since the rise of the Gaddafi regime

After the Libyan King Idris was deposed by Muammar al-Gaddafi in 1969, Libya's demands for reparations were re-emphasized. When Italy rejected the renewed demands, Gaddafi used the anti-Italian resentment of the Libyan population to consolidate his power. In the first year of his reign, he expelled the remaining 20,000 Italians and had their property expropriated without compensation. In the 30 years that followed, Italian-Libyan relations made little progress. Gaddafi continued to regularly demand financial compensation from Italy, while the Italian government insisted that Italy had fulfilled all its obligations under the 1956 agreement. From the 1980s, support for international terrorism by the Gaddafi regime also stood in the way of reconciliation. At the same time, Gaddafi tried not to completely sever economic relations between the two countries and deliberately remained silent on particularly sensitive diplomatic issues such as the Italian concentration camps.

Italian-Libyan relations only improved following the gradual lifting of UN sanctions, which took place from 1998 to 2003. In a joint statement in 1998, the Italian government admitted responsibility for colonial crimes in Libya for the first time in a short and general text. Italy promised Libya technical assistance in clearing WWII mines, but not reparations. In 1999, Italy's left-wing prime minister, Massimo D'Alema , paid a state visit to Tripoli. As the first Italian Prime Minister, D'Alema publicly commemorated the victims of Italian oppressive politics during his state visit in front of the Shara Shiat monument. However, the reconciliation process also experienced setbacks, particularly as a result of revisionist statements by Italian politicians. In 2003 Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi declared that Italian fascism had been "far more benign" than the regime of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein , who had just been ousted . According to Berlusconi, Mussolini "didn't kill anyone" but "sent people on forced leave".

In the summer of 2008, during Berlusconi's state visit, Italy and Libya surprisingly concluded a "friendship and cooperation agreement" in which Italy officially apologized for the colonial period from 1911 to 1943. At the signing of the contract, in the presence of 300 relatives of those Libyans who had been deported to Italy during the war, Berlusconi said: "On behalf of the Italian people, I feel obliged to apologize and to show our pain for what has happened and what has happened marked many of your families.” In addition to close cooperation between the countries in economic terms and migration policy, the contract also provided for 5 billion US dollars (3.4 billion euros) in reparations from Italy. During a return visit by Gaddafi in 2009, both heads of state emphasized the good friendly relations between their countries. The Swiss historian Aram Mattioli (2010) praised the Italian-Libyan reconciliation policy of both heads of state as "historic", but at the same time criticized it as "modern selling indulgences" because of the political calculations practiced in it.

Reception in society and historiography

Contemporary interpretations

Perception in Italy and the international public

Reporting on the "reconquest" of Libya in Italy was dominated by ultra-nationalist propaganda . Behind this was a group of journalists that had become influential in the cities as a result of the First World War and the rise of fascism. General Graziani was hailed in the Italian press as a genuine "Fascist hero" and hailed as the avenger of "Romanism". Information about the atrocities committed by colonial troops in North Africa was withheld from the general Italian public due to prevailing censorship . The emergence of a critical counter-public was thus made impossible from the outset. Despite the fact that large-scale military actions were being carried out in Libya, the press often presented the campaigns to the Italians only as "police actions" or "restoring order". Only an inside circle of officers knew of the extent of the genocidal act in Cyrenaica.

At the same time, General Graziani published several books on his campaigns in Libya, such as Verso il Fezzan (“Against Fezzan”, 1929), Cirenaica pacificata (“Pacific Cyrenaica”, 1932) and La riconquista del Fezzan (“The Reconquest of Fezzan”, 1934). These works were subsequently summarized in Graziani's Pace romana in Libia ('Roman Peace in Libya', 1937). In the work on Cyrenaica and the summary that follows, Graziani speaks clearly of concentration camps for tens of thousands of people in the summer of 1931, with the publications also containing numerous photographs of the camps. Both books were widely circulated in the 1930s. In it, Graziani cultivates an apologetic narrative , defending the internment of the Cyrenean population as an act of “civilization” and “legal” punishment for a recalcitrant and dangerous nomadic population . He compared his “fascist Limes” – the hundreds of kilometers long barbed wire fence on the border with Egypt – to the Great Wall of China . General Attilio Teruzzi also wrote a book called Cirenaica verde (“The green Cyrenaica”, 1931), in which he recorded the war in Cyrenaica from 1926 to 1929. In his foreword to Teruzzi's book, Mussolini also commented on the situation in Cyrenaica: According to the dictator, it was now "green with plants" and "red in blood".

The press in the Arab world took up the topic, which was censored in Italy, with outrage. The contemporary Libyan historian Tahir al-Zawi described the deportation of the people from Cyrenaica as the “ Judgment Day ”: the internees looked like the human skeletons dressed in rags that, according to the Koran , were removed from their graves by God on Judgment Day be resurrected. In Europe, however, indifference prevailed.

The Dane Knud Holmboe delivered a highly critical description of Italian warfare in the travelogue Ørkenen Brænder (1931). On his car trip from Morocco to Darna in Libya in 1930, he experienced the Italian use of poison gas, the conditions in a concentration camp near the town of Barke and mass executions before he was arrested. "The country was swimming in blood," is how Holmboe sums it up. Holmboe also reported that the Italians had thrown arrested resistance fighters out of planes or had them run over by tanks as punishment. However, John Wright (2012) rates this information as "greatly exaggerated" and Giorgio Rochat (1981) also states that this "widespread rumor" cannot be confirmed with documents. In his book Italy in the World , published in 1937, the Austrian journalist and contemporary witness Anton Zischka described the deportations in Cyrenaica, which he classified as "one of the greatest migrations of peoples of our time".

Libyan folk poetry

The majority of people interned in the concentration camps were illiterate semi-nomads. Therefore, their ancient tradition of oral tradition and a strong folk poetry (Arabic al-Shiʿr al-Shaʿbi ) provided the most reliable methods for recording their traumatic experiences. In this form, their memories served as a cultural source for emotional purification and creative expression. Each concentration camp thus had its own poets who incorporated and recorded aspects of the genocide in their works. The most famous poem among Libyans is Mabi-Marad ghair dar-al-Agaila ('I am not sick except for Agaila') by Rajab Buhwaish al-Minifi. Al-Minifi, a Koran scholar from the tribe of guerrilla chief Omar Mukhtar, was interned in the Agaila concentration camp from 1930 to 1934 and wrote the poem while he was in prison. After Libya's declaration of independence on December 24, 1951, it was broadcast regularly on the newly founded Libyan radio and printed in numerous publications. Generations of Libyans became familiar with the poem in this way and at least vague memories of the concentration camps were kept alive.

The second poem that became prominent in the memory of the concentration camps was Ghaith al-Saghir ("Little Ghaith") by later Libyan national poet Ahmad Rafiq al-Mahdawi (1898-1961). Al-Mahdawi came from a respected, educated, urban middle-class family who had been involved in anti-colonial resistance since 1911, and was exiled three times. In 1934 he was able to visit the Magrun camp and the orphan school, where infants and starving children were enrolled, and worked this experience into the hundred-line epic Ghiath al-Saghir . Unlike al-Manifi, who composed his poem Madi-Marad in the local Libyan Arabic dialect, al-Mahdawi composed Ghaith al-Saghir in standard Arabic. After independence in 1951, al-Mahdawi's poem became compulsory reading for all sixth graders in Libyan schools.