Oromo (ethnic group)

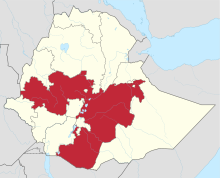

The Oromo (own name Oromoo ) are an ethnic group that lives in Ethiopia and northern Kenya . In Ethiopia they are according to official figures with around 25.5 million - corresponding to 34.5% of the total population - numerically the largest people and have their own state of Oromia . More than 200,000 Oromo live in Kenya, mainly from the Borana and Tana Orma subgroups , mainly in the eastern region . The Oromo language , called Afaan Oromoo or Oromiffa , is one of the East Cushitic languages .

Historically, the Oromo were also called Galla by the Habesha and Somali . This designation, the origins of which are unclear, was sometimes used disparagingly, but at times it was also used in scientific language. Today it is rejected by the Oromo and is considered out of date.

history

The Oromo region of origin is probably in the southern Ethiopian highlands, from where other lowland East Cushite-speaking groups such as the Afar - Saho and the Somali moved to their present-day areas. However, its exact location remains controversial.

Expansion in the 16th and 17th centuries

In the 16th century the Oromo began a great expansion movement, which led north and west to large parts of Ethiopia and south to what is now Kenya and southern Somalia . The driving force behind this expansion is likely to have been a reorganization of the Gadaa age class system , within the framework of which warriors were regularly sent out. The fact that the Oromo region of origin was rather inhospitable may have contributed to the spread. In addition, the costly wars between Ethiopia and the Muslim sultanate of Adal under Ahmed Graññ had weakened both sides, so that they could do little to counter the advance of the Oromo. In the course of the 16th and 17th centuries, Oromo reached as far as Arsi , Shewa , Wollega , Gojjam , Hararghe , Wollo and the east of Tigray and there oppressed the Amhars as well as the Sidama and the Afar . In the east they penetrated as far as the area around Harar and thus contributed to the complete collapse of the Sultanate of Adal. In these very different areas, some Oromo kept their traditional way of life as nomadic ranchers , while others became sedentary farmers. Parts of the Oromo became Muslims or Christians, others kept their traditional religion.

The earliest known written mention of the Oromo comes from the Ethiopian monk Bahrey , who wrote a detailed "History of the Galla" at the end of the 16th century. According to him, the Oromo originally belonged to two subgroups ( Moieties ), the Baraytuma or Barentuma and the Borana .

The Borana, who moved south, displaced or assimilated somaloid groups (such as the Gabbra and Sakuye ) and eventually controlled a vast area between the Tana and Juba rivers in what is now Kenya and Somalia.

Conquest by Ethiopia and incorporation

Under Sissinios the integration and assimilation of parts of the Oromo into the state and society of the remaining Ethiopia began. Oromo adopted the language, religion, culture and economy of Christian Ethiopian farmers in those areas, and today there are millions of Christian Oromo, most of whom speak Amharic , especially in Wollega, Wollo and southern Shewa . Oromo were also accepted into the Ethiopian nobility as allies of Sissinios. In Shewa, a large part of the linguistically and culturally Amharic population consists of amharized Oromo, so that the Amhars living further north regarded the Amhars of Shewa as "Galla" (Oromo). In the Gibe area , meanwhile, agricultural developments began at the end of the 17th century, which led to the formation of the Oromo and Sidama states in the 19th century . These centralized, monarchical states differed from the traditional, egalitarian form of society of the Oromo.

Oromo were captured by Ethiopians as well as by the Gibe states and sold as slaves. Onesimos Nesib , who translated the Bible into Oromo, and the young woman Machbuba were known freed Oromo slaves. The kingdom of Jimma had many slave markets until the mid-19th century. The largest slave market was Hirmata, held every Tuesday near the palace.

At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, Ethiopia annexed large areas in the south and west under Menelik II - King of Shewa and from 1889 Emperor of Ethiopia. These included areas that Ethiopia had to give up in the 17th century. Oromo assimilated in the Ethiopian ruling class also took part in these conquests, which brought most of the Oromo under Ethiopian rule. The fact that their various subgroups and states did not unite against their common enemy contributed to the Oromo defeats. Rather, the Borana , Arsi, and Guji viewed each other as enemies well into the 20th century.

The peasants in the conquered areas became taxable subordinates ( gäbbar ) who were subordinated to Amharic soldiers and other settlers ( neftegna or näftäñña ).

From the east, Somali, especially from the Darod clan, had been advancing into the interior of the country since the 18th century and displacing the Oromo in parts of eastern Ethiopia. Some eastern Oromo groups have been Islamized and Somaliized, and mixed groups have emerged that consider themselves both Oromo and Somali. In the 19th century, the expanding Somali also reached southern Somalia and Kenya, where they almost completely displaced the Borana from Jubaland and what is now the northeast region of Kenya. The British colonial power in Kenya tried with moderate success to hold back the Somali advance at the expense of the Oromo. At the same time, it stopped any further expansion of Ethiopian rule to the south.

Situation in the 20th century

From the beginning of the 20th century, a feeling of togetherness and nationalism ( Oromumma , "Oromo-being") gradually began to develop among the Oromo, which were heterogeneous in religion, economic practices and political structures .

The occupation of Ethiopia by fascist Italy 1935–1941 was connected with the abolition of the gäbbar system and was therefore welcomed by some Oromo. Oromo leaders in the western Illubabor and Wellega regions initiated a movement for the separation of Ethiopia and in 1936 petitioned the British government to become a British protectorate. After the reinstatement of Haile Selassie , there was various resistance to the reintroduction of the old taxation and land ownership system in the 1940s and 1950s. In Tigray , the Rayya and Azebo orromos took part in the Woyane revolt.

In the 1960s in particular, various cultural, social and political movements emerged. At this time, numerous African states gained their independence from the European colonial powers, and many educated Oromo saw parallels with their own efforts to "free" themselves from the Ethiopian conquest - which they viewed as colonialism - and from the hegemony of the Amharen within Ethiopia. In the highlands of Bale province , the Bale revolt began in 1962 , which could not be put down until 1970, and in the highlands of Hararghe , the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) led a guerrilla fight in the mid-1960s. The "Macha and Tulama Self-Help Association" founded in 1962, which initially dealt with self-help development projects, but soon also demanded political and cultural freedoms for all Oromo, was banned in 1966 by the government of Haile Selassie.

After the fall of Haile Selassie and the coming to power of the communist Derg military government in 1974, the public use of the Oromo language was allowed, the name Galla was officially abolished, and in particular the land reform of 1975 met with approval from the Oromo, as it contained elements of Neftegna -System eliminated. However, food requisitions for the army and the cities and the "cleansing" of farmers' associations and the All-Ethiopian Socialist Movement (MEISON) caused displeasure. In addition, Amharic farmers were resettled in Oromo areas, and the Ethiopian alphabet was established to spell the Oromo in the state literacy campaign , although the Latin alphabet had been used since the 19th century. Parts of the Oromo joined the armed resistance against the Derg regime as early as 1974. That year a new Oromo Liberation Front was established. At the beginning of 1977 she controlled the Chercher area in the highlands of Hararghe and was also active in Bale, Arsi and Sidamo .

Somalia under Siad Barre founded the Somali Abo Liberation Front (SALF) in 1976 to mobilize Muslim Oromo to fight for Greater Somalia ; In its claim to "West Somalia" ( Ogaden ), Somalia also included areas predominantly inhabited by Oromo and assumed that it would be able to Somaliize the Oromo in question. Just like the Ethiopian (Amharic) elites, it viewed an independent Oromo nationalism as a threat to its interests. In contrast to the Western Somali Liberation Front with the Ethiopian Somali, however, the SALF only met with moderate support from the Oromo population. Somali troops that penetrated into Oromo areas in the 1977/78 Ogaden War treated Oromo civilians much worse than Somali civilians.

In 1979 an offensive began against the OLF in the eastern highlands (Hararghe, Bale, Sidamo, Arsi) and at the same time against the WSLF in the lowlands. This phase of the conflict had more serious consequences for the population than the actual Ogaden war. The number of war displaced persons within Ethiopia, which had stood at half a million in 1978, rose to over 1.5 million by 1981. Regions that the Ogaden War had never reached were also affected. In mid-1978, 80,000 to 85,000 refugees from Ethiopian territory lived in Somalia, at the end of 1979 there were 440,000–470,000 and at the end of 1980 around 800,000 Ethiopian Somali and, above all, Oromo. Especially in the highland areas (Bale 1979–1982, Hararghe from 1984) millions were forced to resettle in villages under government control in order to cut off the rebels from their base of support. From 1981 the OLF expanded its military activities to the Wollega region in the west.

Political situation

After the fall of the Derg regime in 1991, under the victorious People's Liberation Front in Tigray (as part of the EPRDF political coalition ), the administrative structure of Ethiopia was reorganized according to the principle of “ethnic federalism”. The Oromo also received their own state of Oromia for the first time , which includes most, but not all, of the Oromo areas. The EPRDF founded the Oromo People's Democratic Organization (OPDO) as its partner among the Oromo, while marginalizing the OLF. First the state capital Addis Ababa (called by the Oromo Finfinnee or Shaggar ), where 19.51% of the population is Oromo, also became the capital of Oromia. In 2000, however, she was replaced by Adama , which caused controversy. The disputed between Oromia and the Somali region Harar with 56.4% Oromo became an independent region with the Aderi as the titular nation, Dire Dawa with 46% Oromo, 24% Somali and 20% Amharen became an independent city. The border areas between Oromia and Somali also remain controversial. Oromo also live as a minority on the eastern edge of the Ethiopian highlands in the Amhara region - where an Oromia zone exists - and in the woreda Raya Azebo in the Tigray region , where the Rayya and Azabo live as the northernmost subgroups.

The introduction of the regional division based on ethnicity has strengthened the feeling of togetherness within the various subgroups (e.g. Arsi , Borana , Guji , Macha , Ittu , Anniyya ). At the same time, relations with neighboring ethnic groups changed in some places, which were earlier in some Oromo groups than relations with other Oromo (for example, the Gabbra and Garre on the border with the Somali or between the Guji and Sidama ).

Oromo also complain about repression by the Ethiopian central government. The Oromo Liberation Front campaigns for an independent Oromo state by force, but largely unsuccessfully. The central government and the OPDO-led regional government of Oromia, which forms a coalition with it, therefore see any expressions of Oromo culture, Oromo nationalism and political criticism outside the OPDO as a potential threat. Oromos who support or are accused of supporting independence are being persecuted.

Between the EPRDF-loyal OPDO and the militant OLF, further parties have formed under the Oromo, such as the Federal Democratic Oromo Movement (OFDM or WAFIDO) and the Oromo People's Congress (OPC). The opposition coalition of parties, the United Ethiopian Democratic Forces (UEDF), is particularly popular with Oromo with its advocacy of stronger federalism. But also the Coalition for Unity and Democracy (Qinijit), which as the second major opposition coalition, on the contrary, again advocates more centralism, was elected by Oromo in the 2005 parliamentary elections in protest against the EPRDF. Wolbert GC Smidt writes about those elections: "(...) the result can be so pointed that the Oromo were the first people of Ethiopia to achieve party pluralism."

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ Central Statistical Agency : Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census Results ( Memento of March 5, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 4.7 MB), p. 16

- ↑ Estimates of the numbers of the Borana and the Orma

- ^ Paul TW Baxter: Galla , in: Siegbert Uhlig (Ed.): Encyclopaedia Aethiopica , Volume 2, 2005, ISBN 978-3-447-05238-2

- ↑ Harold G. Marcus: A History of Ethiopia , University of California Press, new edition 2002, ISBN 0-520-22479-5 (pp. 34–38)

- ↑ Oromo Migrations and Their Impact , in: Ethiopia: A Country Study , 1991

- ^ Bahrey: History of the Galla , 1593. Translated by CF Beckingham and GWB Huntingford. In: Some Records of Ethiopia 1593-1646. The Hakluyt Society , London 1954.

- ^ Günther Schlee : Identities on the move: clanship and pastoralism in northern Kenya . Manchester University Press 1989, ISBN 978-0-7190-3010-9 , pp. 25, 35, 38

- ^ Marcus 2002 (pp. Xvi, 43)

- ↑ Gerry Salole: Who are the Shoans? , in: Horn of Africa 2, 1978, pp. 20-29.

- ↑ Marcus 2002 (pp. 45, 56)

- ↑ Seid A. Mohammed: A social institution of slavery and slave trade in Ethiopia. nazret.com, March 6, 2015

- ↑ Marcus 2002 (pp. Xvii, 65, 79)

- ↑ Tadesse Berisso: Changing Alliances of Guji-Oromo and their Neigbors: State Policies and Local Factors , in: Günther Schlee, Elizabeth Watson (Ed.): Changing Identifications and Alliances in Northeast Africa: Ethiopia and Kenya , 2009, ISBN 978-1 -84545-603-0 (pp. 191–199)

- ↑ a b c d e f Alex de Waal, Africa Watch: Evil Days. 30 Years of War and Famine in Ethiopia , 1991 (PDF; 3.3 MB), pp. 23f., 66-70, 75, 80-91, 229-331, 316-319, 323-329, 350-353

- ^ Ulrich Braukämper: Islamic History and Culture in Southern Ethiopia. Collected Essays , Göttinger Studien zur Ethnologie 9, 2003, ISBN 978-3-8258-5671-7 (p. 15, 136 f.)

- ^ Mohammed Hassen: The Development of Oromo Nationalism , in: Being and Becoming , p. 67

- ^ Gebru Tareke: The Ethiopia-Somalia War of 1977 Revisited , in: International Journal of African Historical Studies 33, 2002

- ^ Human Rights Watch: Suppressing Dissent. Human Rights Abuses and Political Repression in Ethiopia's Oromia Region , 2005 (PDF; 318 kB)

- ↑ Abdulkader Saleh, Nicole Hirt, Wolbert GC Smidt, Rainer Tetzlaff (eds.): Peace spaces in Eritrea and Tigray under pressure: Identity construction, social cohesion and political stability , LIT Verlag, Münster 2008, ISBN 978-3-8258-1858-6 (Pp. 224, 349)

literature

- Paul TW Baxter, Jan Hultin, Alessandro Triulzi: Being and Becoming Oromo. Historical and Anthropological Inquiries. Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, Uppsala 1996, ISBN 91-7106-379-X .

- Eike Haberland : Galla of southern Ethiopia. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart 1963 ( publication by the Frobenius Institute at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main: Völker Süd-Ethiopiens 2).

- Ioan Myrddin Lewis: The Galla in Northern Somaliland . In: Rassegna Di Studi Etiopici, Vol. 15, 1959, pp. 21-38, JSTOR 41299539

- Thomas Zitelmann: Nation of the Oromo. Collective identities, national conflicts, we-groups. The construction of collective identity in the process of refugee movements in the Horn of Africa. A social anthropological study using the example of the saba oromoo (Oromo nation). Das Arabisches Buch, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-86093-036-2 (also: Berlin, Freie Univ., Diss., 1991).

Web links

- Oromo Studies Association: Journal of Oromo Studies (English)