Air raids on Frankfurt am Main

About 75 air strikes on Frankfurt were in the Second World War in June 1940 by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and in October 1943 by the United States Army Air Forces flew (USAAF) to March 1945th Over 26,000 tons of bombs fell on the city area. Several attacks from October 1943, especially two so-called thousand bomber attacks on March 18 and 22, 1944, changed the face of the city forever.

According to official statistics, a total of 5,559 people were killed in Frankfurt am Main in the aerial warfare of the Second World War , including 4,822 residents, but also prisoners of war and forced laborers . In the firestorm of the March attacks in 1944, almost all of the important cultural monuments and the entire medieval old and new town with its 1,800 half-timbered houses burned down . Other districts such as Bockenheim , Rödelheim , Ostend and Oberradwere destroyed to over 70%. In total, around 90,000 of the 177,600 apartments in the city as well as almost all public buildings, schools, churches and hospitals were destroyed.

At the end of the war in 1945, Frankfurt's population had fallen from over 553,000 (1939) to around 230,000, half of whom were homeless. About 17 million cubic meters of rubble covered the city.

Preparation for the air war

Shortly after the seizure of Nazi propagandist preparation of the Frankfurt population began an air war. On May 5, 1933, a Frankfurt district group of the Reich Air Protection Association was founded . In March 1934 an instruction in practical air protection took place in the Mühlbergschule in Sachsenhausen , in which one hundred teachers took part. An air defense exhibition in May 1935 drew 120,000 interested Frankfurters to the festival hall . Air raid protection groups were formed in companies and house communities, and from 1936 air raid protection and blackout exercises took place all over Frankfurt. In 1936 Frankfurt , which had previously been demilitarized according to the Versailles Treaty, became a garrison town again as a result of the occupation of the Rhineland . In November 1938, the city published a list of cinemas, gyms and parks that were to serve as places of escape and gathering in the event of air raids.

With the beginning of the war on September 1, 1939, the prepared regulations for air protection came into force. The city of Frankfurt was classified in the top protection category because of its numerous war-important operations. On the night of September 10-11, 1939, British planes flew over the city for the first time and dropped leaflets . By the end of 1939, over 200 public air raid shelters had been completed. Extinguishing water basins were created throughout the city. In February 1940, all house owners in Frankfurt were required to prepare air raid shelters and, above all, to make openings to the neighboring cellars in the old town in order to have escape routes in the event of a fire.

First air raids from June 1940 to December 1942

After several test alarms and overflights without bombing, Frankfurt experienced the first air raid on the evening of June 4, 1940. Around 40 high-explosive bombs , dropped by half a dozen Royal Air Force Handley Page Hampden bombers , struck the Gallus district and hit houses on Schloßborner and Rebstöcker Strasse. Seven residents died and ten were injured. There were twelve more attacks by the end of 1940. The anti-aircraft guns of the air defense could only damage or shoot a fraction of the aircraft.

With the " immediate Führer program " of October 10, 1940, Adolf Hitler ordered the construction of air raid shelters in 60 German cities . In December 1940, construction of the first bunkers began on Glauburgplatz and on Schäfflestrasse, Germaniastrasse and Rendeler Strasse.

From December 23, 1940 to May 6, 1941, the RAF did not fly any air raids, presumably because they were bound over their own territory in the Battle of Britain . During this time, despite the very cold winter of 1940/41, a total of 38 bunkers were built in the city area. Frankfurt was one of the first cities to have a dense network of bunker systems. In addition, there were 24 rescue centers that could provide hospital-independent emergency care.

From May 6th to the beginning of September 1941, the RAF flew 11 attacks with an average of 15 to 20 bombers, which in addition to explosive bombs now also increasingly dropped incendiary bombs . Furthermore, the bombs fell mainly in the outskirts of the city and caused rather isolated damage.

The hitherto heaviest attack took place in the night of September 12th to 13th, 1941. 50 to 60 aircraft in multiple waves dropped 75 explosive and 600 incendiary bombs and, for the first time, 50 phosphor canisters . There were 8 dead and 17 injured; around 200 people were left homeless in 74 damaged homes.

As early as May 1941, Gauleiter Jakob Sprenger had ordered the “utilization of Jewish apartments for German national comrades”. This was intended to legitimize the confiscation of Jewish property in order to compensate bomb victims. The deportation of Jews from Frankfurt began on October 19, 1941 . At that time, around 10,800 Jews were still living in the city. More than 1,100 people were picked up from their apartments, mainly in the Westend , and transported to the Litzmannstadt ghetto via a collection point in the wholesale market hall . Only three of them survived until they were liberated in 1945. The deportees had to draw up a declaration about their property and their household effects, which would later enable them to be confiscated. With the Regulation November 25, 1941 to the Reich Citizenship Law the assets of the deportees fell flat rate to the Treasury .

The 14th and last air raid of 1941 followed on October 24th. It hit the Frankfurt city forest and caused only minor damage to the fields around the Maunzenweiher . Another six months followed without attacks. During this time, the air war situation worsened for National Socialist Germany : The air force, which had already been weakened after the lost Battle of Britain , was increasingly worn out in the war against the Soviet Union . After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 , Germany declared war on the USA on December 11, 1941 . As a result, the American Air Force set up the 8th Air Force , which intervened in the European theater of war from the summer of 1942.

On 14 February 1942, the British gave the Air Ministry , the area bombing directive ( "statement to carpet bombing " ) out with the aim of bombing of apartment buildings instead of military equipment and armament factories the fighting spirit of the civilian population to weaken. The " Dehousing Paper " passed by the British cabinet in May 1942 declared the destruction of eight million houses and 60 million apartments in German industrial cities a strategic goal. The initiators reckoned with 900,000 dead and one million seriously injured among the population. With the air raid on Lübeck on March 29, 1942 , the air war began according to the directive. Attacks on Essen and other cities in the Ruhr area were followed by attacks of unprecedented strength on Rostock (end of April) and Cologne ( Operation Millennium , May 30/31, 1942), which largely destroyed these cities.

Frankfurt experienced only six attacks in 1942 between May 5 and September 9, 1942, the most severe on August 25, 1942, when 50 aircraft around 100 high explosive and 8,000 incendiary bombs hit the northern part of the city and the one that burned out on December 18, 1940 Throwing off the festival hall . In this attack, four-engine bombers and so-called scouts were used for the first time , which marked the intended target area with red and green lights ("Christmas trees"). The procedure was still imprecise, which is why a large part of the bombs destined for Frankfurt fell on locations in the vicinity or in open terrain. An attack of similar strength hit Eschersheim and Höchst on September 9 ; again only a few dozen were injured and some killed. Then another seven months without bombing followed.

In October 1942, 20 air raid shelters with a total of 10,300 places were completed. Two further bunkers in the main train station offered protection for up to 3,000 travelers. 15 urban bunkers and the Reichsbahn bunker at Frankfurt-Höchst station were under construction. Numerous prisoners of war and slave labor were used in the construction work.

By the end of 1942, 67 Frankfurters died in air raids and only individual buildings were destroyed. There had not yet been any significant outsourcing of cultural goods. The former member of the Reichstag, Johanna Tesch, recorded 45 air alarms in her notebook for 1941. For the citizens, urban life was still largely unaffected by the aerial warfare. In other respects the events of the war were already clearly more visible: around 25,000 forced laborers and prisoners of war had been permanently deployed in Frankfurt since 1940. The deportations of Jewish citizens also continued as planned throughout the year. By the end of 1942 almost 10,000 Jews had been deported in a total of 9 transports, of which fewer than 600 saw the end of the war. The responsible tax office had confiscated furniture and other household items stored and auctioned.

The first heavy air raids in 1943

( ruins model from the Historical Museum )

At the end of 1942, Wehrmacht troops were involved in fighting with the US Army for the first time in the Africa campaign ; January 1943 brought defeat at the Battle of Stalingrad . On February 18, 1943, Joseph Goebbels announced the total war in his Sportpalast speech . A little later, the British and US air forces agreed on the Combined Bomber Offensive , which was to strategically bundle the air strikes on Germany. While the Royal Air Force continued its nightly area bombing of densely populated cities, the US Air Force was supposed to attack industrial plants and infrastructures during the day.

The city budget and ultimately the citizens of Frankfurt increasingly felt the increasing burden of the war. At the same time, the psychological stress on the population increased as a result of the reports of the considerable destruction of other major German cities and threats that were spread by means of leaflets dropped in large numbers . One of the leaflets read: “What you experienced that night were only the first drops that heralded the coming storm. But it will rain down on you more and more powerfully, more and more destructively, until you can no longer withstand the elemental force of the hurricane. "

Nevertheless, the year 1943 remained calm until the nocturnal attack by a squadron consisting of 15 to 20 aircraft on April 11th. The approach was imprecise; the around 50 high-explosive bombs and 4,500 incendiary bombs distributed over the entire city area and Offenbach only caused sporadic destruction and damage, including on the Sachsenhausen mountain.

In July 1943, 35,000 people died in a firestorm in heavy air raids on Hamburg ( Operation Gomorrah ) . Many Frankfurters feared the same in densely built-up Frankfurt. On August 12, 1943, the first extensive evacuations of school children began. The prerequisite for this was created by a decree by the Reich Youth Leader Baldur von Schirach on June 15, 1943. He ordered the expanded Kinderlandverschickung , that is, the closed relocation of entire schools, so that no students who were left behind did not have to be distributed to other classes or to teach in collective schools.

The attack of October 4, 1943

On October 4, 1943, the city experienced the first major attack: in the morning the Heddernheim copper works were deliberately bombed (which also caused damage in Heddernheim itself as well as Bonames and the Roman city ).

In the late evening hours, an area attack on the urban area followed, in which 402 British bombers - 162 Lancaster , 170 Halifax and 70 Stirling - and 3 US B-17s took part. Before the attack, the target area was marked by 4 Mosquito high-speed bombers. This was monitored by a master bomber flying at high altitude, which was in radio contact with the marker pilots. After this was finished, the master bomber checked the Frankfurt target area again on a lower flight path, determined the exact approach heights and cleared the attack. At 9 p.m. the sirens wailed in the city.

The attack that followed lasted two hours. His goal was to kindle a firestorm like the one in Hamburg. In preparation for such air strikes, a precise selection of the parts of the city to be bombed was made on the basis of aerial photographs, population density maps and fire insurance cadastre maps. Before the war, German fire insurance companies deposited the cadastral maps with British reinsurance companies . The historic Frankfurt old town was selected as the core area of the attack, as the proportion of wood in the total building mass was highest here.

First, 4,000 high-explosive bombs and 650 air mines were dropped. The pressure waves from the explosions were supposed to tear open the roofs and cover the roof tiles. Then 217,000 stick bombs and 16,000 phosphorus canisters fell on the target area, which now struck the roof trusses of the houses and set them on fire very quickly. Within an hour, thousands of smaller building fires spread to major fires in several parts of the city, which were only completely extinguished after several days. The dreaded firestorm did not materialize. Nevertheless, severe damage was caused, especially in the east of Frankfurt. In the Alte Gasse, the Große Friedberger Straße, the Friedberger and the Obermainanlage , in the zoological garden , at the Ostbahnhof , around the Ostpark , on the Hanauer Landstraße , in the eastern Sachsenhausen and in Oberrad whole streets burned down due to the effects of fire bombs. Kleinmarkthalle and Großmarkthalle were badly damaged. In the old town, the area between Neue Kräme , Liebfrauenberg , Tönges- , Trier- and Hasengasse, built after the Great Christian Fire in 1719 , suffered severe damage.

529 people died, many more were injured , some seriously . 108 people died in Oberrad. With a direct hit on died shelter of (the former Israelite Hospital furnished) Children's Hospital at the Gagernstrasse in Ostend 90 children and 16 employees, which by -Nazi propaganda via the same switched denounced press as cruelty of the Allies or as "Frankfurt Children's murder." A total of 835 buildings were destroyed or badly damaged by the attack, and almost ten thousand Frankfurters were made homeless by the attack. The attackers lost 11 machines.

Important architectural monuments, including the historic churches, were largely undestroyed during this attack. In the Paulskirche five fire bombs broke through the slate roof and got stuck in the roof structure. The fire watch in the church managed to find the burning bombs and remove them before the fire could spread. Part of the roof structure burned down on the Liebfrauenkirche . The Teutonic Order Church in Sachsenhausen was badly damaged and the neighboring Teutonic Order House destroyed. Of the public buildings, the Roman was hardest hit when many roofs also burned down here from the effects of incendiary bombs and destroyed the precious rooms below. The former patrician residences Haus Lichtenstein on the Römerberg as well as the houses Grimmvogel and the Große Braunfels on the Neue Kräme were also badly damaged by the monuments . Both churches in Oberrad, the Protestant Church of the Redeemer and the Catholic Church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus , burned down .

The psychological consequences of the first major attack were considerable. The recovery of the dead took several days. Many Frankfurters left the city for fear of further attacks or spent the night in the open. The synchronized press criticized this behavior as "cowardly" and "undignified". At the same time, she tried to stir up hatred of the attackers. The victims of the bombs were celebrated as dead, the emergency services engaged in fire-fighting and clean-up work as heroes. On October 10, the NSDAP held a large funeral service on Opernplatz . Most of the victims were buried in the Oberrad forest cemetery.

Allied prisoners of war in the West End

In the summer of 1943, the construction of a prison camp began in Grüneburgpark . It was designed as a transit camp Dulag Luft and replaced a smaller camp in Oberursel . Russian prisoners of war were used as slave labor during the construction. From September onwards, all Allied air force soldiers who had been shot down and captured over Germany were brought here and, after they were recorded, distributed to one of the main camps with collective transports . In September 1943, 868 prisoners were registered, in October 1502.

The location in the Westend was in the middle of the city, in the core area most threatened by air raids. According to Gauleiter Sprenger, the prisoners should serve as human shields . The construction of the camp thus violated Article 9 of the Geneva Convention “On the Treatment of Prisoners of War”.

The camp remained unscathed in the heavy attack on October 4, 1943. In December the British government protested against the relocation of the Oberursel camp. As a result, the camp received air raid shelter in the form of fragmentation trenches , bunkers and extinguishing water ponds.

The Dulag Luft was only in operation for six months until the air raid on March 22, 1944.

Further attacks in 1943

After a relatively small night attack on October 22 with 50 aircraft, which caused damage mainly in the Riederwald, a large night attack with 262 aircraft (236 Halifax and 26 Lancaster) followed on November 25. For a long time, the German anti-aircraft defense system was based on Mannheim as the target and only recognized the actual target late, so that only 12 aircraft were shot down. 247 high-explosive bombs and around 150,000 incendiary bombs caused damage, especially in the old town, without igniting a firestorm. The next big attack with 650 bombers - 390 Lancaster, 257 Halifax, led by 3 Mosquitos - followed on December 20, 1943. This time the German air defense recognized the target early and already disrupted the approach. 41 bombers were shot down. In addition, the target marking was imprecise and visibility was very poor, so that many bombers did not reach their target. Nevertheless, the city of Frankfurt, especially the old town and the industrial areas East and West, Fechenheim and Sachsenhausen, were bombed by around 200 aircraft. The attack with 970 high-explosive bombs and 450,000 incendiary bombs lasted over an hour and triggered 164 major fires, as well as numerous smaller fires. The old city library and the Rödelheimer Schloss were hit, among others . 175 people died, 23,000 were left homeless, and 104 industrial companies were badly hit. On December 22, 1943, a small attack with 9 mosquito bombers followed, which caused minor damage in Höchst.

The destruction of Frankfurt in March 1944

The daytime raid on January 29, 1944

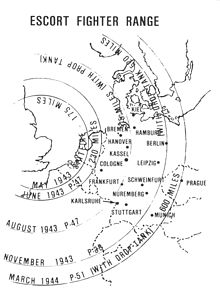

The next major attack occurred on Saturday, January 29, 1944. The new American Mustang long-range fighters were now able to accompany the bomber units to their targets and also during the attacks, so that the German air force was less and less able to do anything against the incoming units. The H2X radar enabled the American associations to fly even in the worst weather, which was also dangerous for the single-engine German fighter planes.

Of 863 heavy bombers launched by the US 8th Air Fleet, over 800 dropped around 5,000 high-explosive bombs and 120,000 incendiary bombs over the entire city area at lunchtime under the protection of 630 fighters. 34 attacking bombers and 15 escort fighters were shot down by the German air defense, which however lost 47 fighters itself. The attack claimed over 900 lives. Many were buried in their houses because a particularly large number of high- explosive bombs had been dropped with delay detonators during this attack , which often penetrated several floors and only detonated on the ground floor or in the basement. In the basement of a print shop in Grosse Bockenheimer Gasse alone , 40 people were killed by falling machine parts. 120 people were locked in the house of the Diesterweg publishing house in the Großer Hirschgraben . Even days later, individual bombs exploded during the rescue work and triggered individual fires.

The attack destroyed nearly 3,000 homes, leaving around 25,000 people homeless. In addition to the playhouse , numerous public buildings were hit. Six direct hits by high-explosive bombs almost completely destroyed the neo-Gothic city archive on the Weckmarkt. Numerous irreplaceable files were lost because the city archives had long hesitated with the decision to outsource cultural assets, which had already been decided in 1942. The cathedral was also hit by two high-explosive bombs. For the first time, the city's public life was also affected. The south wing of the main station was in ruins, plus many houses and hotels at the main station and in Kaiserstrasse . Roads were torn open by bomb craters, the overhead lines of trams were destroyed and the supply of gas, electricity and water in the affected districts was interrupted for a long time. This also had consequences for future attacks, as in some cases only surface water was available for fire fighting , which had to be taken from extinguishing water ponds or the Main and transported with hose lines from the fire brigade.

After the attack on January 29, 1944, life in the city changed. In the next two months, tens of thousands left the city to seek refuge in the countryside. Whole school classes were gradually moved to the countryside with their teachers. But still more than 36,000 people lived in the narrow streets of the old town. Cinemas and theaters continued to operate, but there were no more performances in the evenings.

February 1944

In February 1944, the American Air Force carried out several daytime raids. On February 4th, industrial areas in the north were the target, but the bombs fell mostly in open terrain. On February 8, 1944, 81 B-17 bombers of the 8th Air Force attacked again during the day. Actually, the attack should be directed against the Teves plant in the Gallusviertel . Instead, the bombs fell in two waves on the main plant of Hartmann & Braun in Bockenheim. The neighboring factories of Pokorny & Wittekind and the Bauersche Gießerei as well as the Sophien and Falkschule are damaged, and the Markus Hospital in Falkstrasse is completely destroyed. The attack left 348 dead, including 165 in the air-raid shelter at Hartmann & Braun, and around 200 seriously injured. Journalist Alfons Paquet died of a heart attack during the attack in the basement of his house on the banks of the Main .

On February 11, the US Air Force launched an attack on the United German Metal Works (VDM) in Frankfurt-Heddernheim , where variable-pitch propellers were manufactured for the Air Force aircraft. About 150 bombs fell in the open area.

The heavy US daytime attacks represented a new quality of threat for many Frankfurters because there were a lack of protective equipment in many large companies and it was forbidden to leave the companies in the event of an alarm. Many broke the ban. The bad mood also preoccupied the National Socialist leadership. In a “rumor collection report” of the NSDAP of February 12, 1944 it says: “The daytime attacks made the population very nervous. Gradually one had come to terms with the dangers of the night. Those who seriously speak of retribution - jokes about it are popular - encounter little understanding and belief. The vast majority are aware that we have nothing to expect in the event of defeat. "

In the following four weeks, the Frankfurters were spared further serious attacks. During Big Week from February 20-25, 1944, the Allied air raids concentrated on the final assembly plants for German aircraft production. It was not until March 2, 1944 that the next day's attack by strong formations followed. However, due to heavy snowfall, visibility was obstructed, and the radars did not allow safe navigation. The attackers missed their target and dropped their bombs on the neighboring communities of Bad Vilbel and Bergen-Enkheim as well as on Seckbach , Riederwald and Fechenheim . The attack claimed 94 lives and damaged the main water line from the Vogelsberg . After that there was an almost daily alarm about enemy attacks in the Rhine-Main area , but without further air strikes.

Saturday March 18, 1944

On the night of March 18-19, 1944, 846 British bombers - 620 Lancaster, 209 Halifax, 17 Mosquito - launched a major attack on Frankfurt. The association came from the Channel coast and took the route via Liège-Trier in the direction of the Rhine-Main area. Because of a parallel mine-laying operation by the Royal Air Force in the North Sea north of Heligoland , the German air defense had split its hunting units. The German night fighters were only able to attack the stream of bombers shortly before the target. The poor visibility made the search difficult for the fighters. Only 22 bombers were shot down this time.

This time, however, the British scouts succeeded in precisely marking their target area in the inner city of Frankfurt. At 9:13 p.m. the sirens wailed in the city, and shortly after 9:30 p.m. the first bombs fell. The attack lasted about an hour and hit the eastern old town in several waves. A wide swath of devastation stretched from the old bridge to the Konstablerwache . All the houses in the Fahrgasse and at the Garkarkplatz were destroyed, including the Fürsteneck house and the flour scales . The Fischerfeldviertel and the Hospital of the Holy Spirit were badly hit. The Carmelite Monastery and Paulskirche were also hit by several bombs and burned out completely. At the beginning of the attack, an air raid force of around 30 people had gathered in the Paulskirche. Towards the end of the air raid, a few incendiary bombs broke through the slate roof and set fire to the framework of the roof ridge. The four hydrants around the church gave no water because of the pressure drop in the water pipes. The existing hoses were not sufficient to bring water from the extinguishing water ponds on the Römerberg, and there was a lack of pumps. The professional fire brigade had orders to use the existing equipment primarily to protect industrial plants. So the fire ate its way through the beams. It took more than an hour to bring a small, portable fire engine into position, but the small amount of water was not enough to bring the fire under control.

“And then suddenly a thud, never heard before, devouring every other sound. It's like the earth is bursting. The still burning parts of the roof fall into the church, as if blown off above, knock down the gallery resting on pillars with its 1200 seats, the seething, glowing mass buries the nave under itself, presses the asbestos walls to the tower like cardboard covers, and now also sets the interior of the tower on fire. As in an enormous cauldron, it cracks and bursts and screeches in the ears of the crew of the protection troops, silent with horror, who are squeezing themselves outside in nooks and crannies of the town hall walls. The fire stands like a giant torch over the city and reaches up into the blood-red sky. "

Towards the end of the attack, the stream of bombers dispersed. Some of the bombs also fell in western parts of the city, for example on Rödelheim, Niederrad , the Gutleutviertel and the Hoechst paintworks . According to the Royal Air Force's war diary, it was usually more difficult for the rear waves in large formations to hold their formation, especially since inexperienced crews were usually assigned to the last wave of attack.

That night, 421 people died in the city and 55,000 were left homeless. 7000 residential buildings were destroyed. Although the fire brigades and other volunteers from Darmstadt, Wetzlar, Hofheim, Großauheim and other places in the Rhine-Main area rushed to help, they were unable to do anything against the major fires.

Wednesday March 22, 1944

Four days later came the next blow, which brought down old Frankfurt. The attack involved 816 aircraft - 620 Lancaster, 184 Halifax and 12 Mosquito - of which 33 were lost. The German air defense had been deceived by a mock attack on Kassel and did not trigger a pre-alarm. The radio reported only a single jamming aircraft over the city.

When the sirens wailed at 9:45 p.m., the attack had already begun. In three waves, the planes dropped 500 air mines , 3,000 heavy explosive bombs and 1.2 million incendiary bombs on the city center. Within a short time, the entire western old town was in flames. The firestorm particularly raged on the Großer Kornmarkt , in the Weißadlergasse and on the Großer Hirschgraben . The Goethe House burned to the ground. More than 150 dead were later found in the overcrowded cellar of the Großer Kornmarkt 20 house alone . They had suffocated because they could not leave the basement in time after the bombs before the subsequent firestorm. Many victims were also buried on Schäfergasse and in the basement of the regional court .

In the quarter between the cathedral and the Römer, too, all the houses burned down, but many people were able to save themselves here. Most of the medieval Frankfurt houses had very solid vaulted cellars, which were relatively well protected against explosive bombs and which had been connected to one another since 1940. In this way they formed an underground network. Many survivors were able to save themselves from the firestorm in the direction of the banks of the Main or the large squares in the old town. Around 800 people sought refuge from the bombs in the Roman cellar and in a cellar in the neighboring Alte Mainzer Gasse. A fire brigade officer had the cellars cleared during the attack against the resistance of the responsible air raid protection station. The people got through the underground passages to an emergency exit next to the extinguishing water basin at the justice fountain .

People also fled from the firestorm from numerous other old town cellars to get an emergency exit. From here the Frankfurt fire brigade had kept an escape route open from the old town to the bank of the Main at the Fahrtor with water veils . Therefore, of the more than 1000 half-timbered houses in the old town, only the Wertheim house , located directly at the Fahrtor, remained undamaged. It was spared from the high-explosive bombs, and even the firestorm could not harm it because of the water veil.

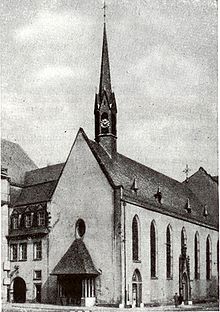

The stone monuments, including the canvas house and the stone house , were also lost. With the exception of the Leonhard Church on the banks of the Main and the - albeit heavily damaged - Old Nikolaikirche , all inner-city churches were destroyed: Katharinenkirche , Liebfrauenkirche , Peterskirche , Dominikanerkloster , German Reformed Church , French Reformed Church and Weißfrauenkirche . The imperial cathedral St. Bartholomäus burned down, even if the tower was only slightly damaged. The tower clock of the Katharinenkirche had stopped exactly at 9:43 p.m. For 10 years, the hands on the burned-out ruin reminded of the time it went down.

The art historian Fried Lübbecke witnessed the attack and destruction of the Schopenhauerhaus at the Schöne Aussicht . In his Farewell to the Schopenhauer House , written in Bad Homburg in April 1944 , he wrote:

“My wife is just pouring the first cup when the few sirens that survived Saturday howl, rather pitifully, the pre-alarm. A view from the balcony shows many spotlights against a bright, hazy night sky. A cascade of green and white sparks floats down, apparently on a straight path towards our roof. At the same moment the first bombs crash without being heard whistling. […] Bomb after bomb rushes down, probably for ten minutes. The huge house sways like a drunkard, through the window holes comes suffocating smoke with the dust, also flickering light. The Secret Annex is on fire. [...]

We hurry down the courtyard stairs to the air raid shelter! A look up: the dwelling is also on fire - the high studio with the three light arched windows, [...] Already there is a crack. The second wave is coming. Again bomb after bomb in close proximity. […]

I stand high up at the corridor window and look north, west and east over the city. Everything is on fire! The rafters of many houses on the Zeil , on Eschenheimer Straße , the Palais Thurn und Taxis, glow like glowing dinosaur skeletons ! The spire of St. Catherine's, the roof of St. Peter's Church, flames! Old Frankfurt is dying! [...]

In the middle of the bridge we stand, under the cross of the bridge cock . […] The heat is so intense that I take off my coat. [...] A sky-high cloud of fire drifts over the roofs towards the Main, driven by the firestorm. It sounds like a deep, rustling organ tone. It howls, cracks, bangs, crackles, whistles, rattles, cracks. In between, the explosions of the time fuses shake . It is exactly ten thirty. The tall houses on the Mainkai , between Fahrgasse and Kleiner Fischergasse, collapse, disappear like backdrops. The roaring noise all around is so monstrous that you can't even hear their fall. Now the cathedral stands tall and free over the Main, over the old bridge. [...] Nobody has seen him like this before. [...] The tip disappears in billowing smoke. [...] Where did the people go? Are you still waiting in the cellars for the all-clear, which the destroyed sirens can no longer give? "

After the attack

A total of 1001 people died in the attack and 120,000 were left homeless. Around 9,000 fires were counted throughout the city. Compared to other German cities badly hit by the air war, the number of victims in Frankfurt remained relatively low. Many victims had suffocated as a result of high-explosive bombs spilling the escape routes from the basements or were killed by the pressure waves of nearby explosions. Even the day after the attack, there were fire in many parts of the city. The fire brigades from all over the surrounding area continued to extinguish the fire for days while the technical emergency aid tried to free those who had been buried and to rescue the dead.

The Dulag Luft prisoner-of-war camp in the Westend was destroyed in the attack, killing two people from flying debris. The next day the surviving Allied prisoners marched to Heddernheim , from where they were transferred by train to the new Dulag Luft in Wetzlar . During the march, the guards had to protect their prisoners from attacks by bombed-out Frankfurt citizens. The camp in Wetzlar existed until American troops marched in on March 27, 1945.

Two days after the major attack of March 22nd, another daytime attack by the 8th Air Force followed. An association of 262 bombers was supposed to attack the ball bearing works in Schweinfurt. Around 175 of them could not find their destination due to poor visibility and instead flew to the alternative destination Frankfurt. The alarm went off at 9 a.m. The attack hit the already badly damaged city center again, where numerous coffins with the victims of March 22nd were waiting to be removed. The victims included rescue teams, but also bombed out people who were waiting at the main train station to be evacuated.

Gauleiter Sprenger declared Frankfurt a “front city” on March 26th and the Rhein-Mainische Zeitung wrote: “We stand man by man and woman by woman on our defense section in the great home front and swear full of hatred and anger against the bestial enemy us and ours People: Front city Frankfurt will be held! ”In the entire city area, a total of 11,000 residential buildings were badly damaged or destroyed in the March attacks, plus 136 public buildings, including schools, hospitals, museums, university buildings, train stations, tram depots and opera houses . More than 180,000 people were left homeless, of whom around 150,000 left the city. Evacuations were strictly regulated and residents were asked to properly re-register. Many survivors were traumatized. Roads were littered with rubble and in some cases impassable, canals and gas pipes were destroyed.

But as early as April 1, 1944, the power grid could be started up again. Individual cinemas and theaters that had not been completely destroyed began to play again in the course of April. The popular Café Rumpelmayer in the Gallusanlage and the restaurant in the Palmengarten also reopened in May, and individual tram lines resumed operations. But the mood in the population did not recover, especially since the war situation on the fronts deteriorated dramatically in the summer of 1944 with the invasion of Normandy and in the east with the destruction of Army Group Center . After a two-month break, the air raids began again, initially with smaller units on individual targets, including the East Freight Station and the Rödelheim industrial area. In addition, there were more and more frequent low-flying attacks.

Further attacks and end of the war

The last major attack on Frankfurt occurred on September 12, 1944. After the destruction of the inner city, it was directed against the north-western parts of the city. Bockenheim in particular was affected. Of the 378 Lancaster bombers and 9 Mosquitos, 17 were lost. The planes dropped 2,000 high explosive bombs and around 240,000 incendiary bombs. The attack caused great damage in the affected districts, especially since a large part of the Frankfurt fire brigade had been assigned to clean up there after the air raid on Darmstadt that had taken place the day before .

An air mine the size of an advertising pillar , weighing 1,800 kilograms , hit the air raid shelter in Bockenheimer Mühlgasse and smashed through the two meter thick rammed concrete wall next to the entrance door. Due to the scarcity of raw materials, the usual iron reinforcement was dispensed with when the bunker was built . The explosion killed 172 people and seriously injured 90. By the end of 1944, nine more day and night attacks on different targets in the city followed. A daytime attack with around 200 aircraft hit the already destroyed city center on September 25th. At Goetheplatz , an aerial mine threw the exactly 100-year-old Goethe monument by Ludwig Schwanthaler from its pedestal, with the head and one arm torn off. The remains of the monument were later buried for fear of metal thieves and finally restored in 1951.

The air raids on Frankfurt continued in 1945 as well, which now mainly took place during the day due to the unrestricted Allied air control and were mainly directed against facilities of the Reichsbahn , transport facilities and industrial areas. The list shows 11 attacks between January 5th and March 13th. The most severe was a daytime attack with around 300 aircraft on March 9, 1945, during which bomb carpets fell on Heddernheim and the industrial area on Mainzer Landstrasse . Two weeks later the hostilities in Frankfurt ended with the occupation of the city by the 7th US Army from March 26 to 28, 1945.

Balance sheet and consequences

Bombing

British aircraft dropped a total of 14,017 tons of bombs on Frankfurt during the war, and American bombers from October 1943 to March 1945 12,197 tons. This puts Frankfurt in eighth place among the most heavily attacked targets of the 8th Air Force and ninth place of the RAF Bomber Command .

Air War Victims

According to official statistics, a total of 5559 people were killed in the air raids on Frankfurt, including 4822 Frankfurters, but also prisoners of war and forced laborers. In comparison, over 18,000 Frankfurter died as soldiers at the front or died in the hospital during the war; over 11,000 Frankfurt Jews were deported and murdered. The exact number of forced laborers deployed and killed in Frankfurt is not known.

Destruction

In the firestorm of the March attacks in 1944, almost all important cultural monuments and the entire medieval old and new town with its around 1250 half-timbered houses burned . 90% of the buildings within the system ring were destroyed or damaged, only five buildings remained undamaged.

Other districts such as Bockenheim , Rödelheim and the districts of Gallus , Bahnhofsviertel , Westend , Nordend , Ostend and Oberrad around the plant ring were also heavily destroyed, in some cases by more than 70%. In other parts of the city the damage was less, some like Eckenheim and Bonames remained almost undamaged.

In total, around 90,000 of the 177,600 apartments in the city as well as almost all public buildings, schools, churches and hospitals were destroyed. At the end of the war in March 1945, the population had fallen from 550,000 (1939) to 230,000, half of whom were homeless. Over 17 million cubic meters of rubble covered the city.

Danger from duds

Duds continue to pose a significant risk, especially in undeveloped areas and in urban forests. According to estimates by the ordnance disposal service , hundreds or thousands can still lie in the ground in the Frankfurt metropolitan area. Experience has shown that around 10 to 20% of the bombs dropped did not detonate on impact. In May 2013, during construction work in Bockenheim, three duds were found within a short period of time, and each time a larger part of the city had to be evacuated for hours during the defusing process. On January 8, 2017, the ordnance disposal service recovered a 50 kilogram American bomb from the Main in the immediate vicinity of the Holbeinsteg . Around 900 residents and hotel guests had to temporarily leave their quarters for this.

During construction work on the campus Westend a column filled with 1.4 tons of explosives British was on 27 August 2017 aerial mine type HC 4000 found. Their defusing required the evacuation on Sunday, September 3rd in a restricted zone of 1.5 km around the site. During the largest evacuation in Germany since the Second World War, over 60,000 residents had to temporarily leave the restricted area.

On December 6, 2020, the defusing of a 500 kilogram bomb in the Gallus , which was found during construction work on December 3, required the evacuation of 12,800 residents. In the evacuation area, among other things, there were data centers with Internet nodes as well as the track apron of Frankfurt Central Station. The evacuation was made more difficult by the strict hygiene requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany .

On May 19, 2021, the discovery of a 500-kilogram bomb in the Nordend led to the evacuation of around 25,000 residents within a radius of 700 meters from the site. The citizens' hospital , the university of applied sciences , the German National Library and several schools were affected by the evacuation . The bomb was discovered during construction work under a children's playground next to a former air raid shelter at a depth of two meters. Due to the design of its detonator, it was not possible to defuse it, only to detonate it in a controlled manner.

Debris removal

Shortly after the American invasion, work began to organize a functioning administration and to repair the infrastructure. The first trams were running as early as April 1945, and theaters and cinemas began to play again in partially provisional conditions. Around 60,000 Frankfurters returned to the destroyed city in the first post-war months. In order to accommodate them, destroyed apartments were poorly repaired. In October 1945 the public gas supply was put back into operation, and the Trümmerverwertungsgesellschaft (TVG) was founded in the same month . With the rubble confiscation ordinance on December 20, 1945, house and landowners were prohibited from rebuilding their destroyed buildings on their own responsibility; Instead, the city confiscated all rubble in the city area, plus all houses that were more than 70% destroyed.

In the summer of 1946, TVG began clearing the rubble plots in the city center with the personal participation of the newly elected Lord Mayor Walter Kolb . Initially with a shovel and pick, later with military equipment from American military stocks, rubble and scrap metal were brought to the Scheffeleck , from where a field train transported them to the rubble recycling facility at Ostpark . By the end of 1947, 26 kilometers of roads had been cleared of rubble. The TVG was able to transport 1500 to 2000, at times even over 3000, cubic meters of rubble away every day. In total, the TVG removed almost 10 million cubic meters of rubble by 1955.

In 1949 the processing and recycling plant for rubble went into operation on the Bornheimer slope . Every year, over 20 million new stones and bricks were created from the rubble that were used in the reconstruction. Around 100,000 apartments and commercial buildings could be built with their help. The rubble recycling plant was in operation until 1964.

reconstruction

In April 1946, before the first local elections, the mayor Kurt Blaum , who was still appointed by the military government, announced the reconstruction of St. Paul's Church. Blaum brought it up as a parliament building for a future German republic. However, the reconstruction of the Paulskirche still faced enormous hurdles: an architectural competition was announced. He found that the reconstruction would cost 2.7 million Reichsmarks. There was also a lack of building materials, machines and labor. In January 1947 Kolb called for donations for the reconstruction of the Paulskirche:

“The democracy that we are now reestablishing also needs your father's house. All German cities and communities should rebuild the Paulskirche, from the outside and from the inside, in stone as in spirit. The Paulskirche should again form the venerable space in whose ascending circle the German people gathers again and again for discussion and celebration. "

With support from all over Germany, it was possible to rebuild the Paulskirche as the first major reconstruction project in Frankfurt by the centenary of the Frankfurt National Assembly on May 18, 1948.

While the reconstruction of the Paulskirche was still largely undisputed, there were disputes over the reconstruction of the Goethe House, which ultimately became characteristic of similar conflicts over other reconstruction projects. In the case of the Goethe House, the proponents of a reconstruction prevailed. In 1951 the rebuilt building was opened.

Overall, however, the city council decided on May 29, 1947, on the recommendation of City Planning Director Werner Hebebrand , that a comprehensive restoration of the destroyed city center was out of the question. The reconstruction should be limited to a few striking monuments, namely the Roman, cathedral, Carmelite monastery, Dominican monastery, Paulskirche and the main front with Saalhof and rent tower . Reconstruction in the old town finally began in 1952. In addition to those mentioned, other architectural monuments were created, including the Dotation Churches and the Stone House , mostly in historical form, while the interior was designed in a modern way. Most of the reconstruction, however, took place without considering the old street and property locations. The formerly narrow old town was rebuilt according to the principle of the car-friendly city and numerous preserved remains of reconstructable buildings were removed, including the Weißfrauenkirche and the German Reformed Church .

In the mid-1960s, the reconstruction was largely complete, with the exception of the area between the cathedral and the Römer in the old town. In the 1970s there were still some prominent ruins: the Christ Church near the university was rebuilt in 1978, the old opera , long known as the most beautiful ruin in Germany , from 1976 to 1981. Its reconstruction was largely carried out by a citizens' initiative. It was not until the early 1980s that the canvas house and the Carmelite monastery were rebuilt and have been used as museum buildings ever since.

In 1983 the half-timbered houses on the east side of the Römerberg were rebuilt and have since been one of Frankfurt's main tourist attractions. Since the beginning of the 21st century, more and more reconstructions of war-torn buildings have been carried out, for example the old city library in 2004 . In 2007 the Dom-Römer project was decided, in which the historic streets Markt , Hühnermarkt and Hinter dem Lämmchen between the cathedral and the Römer were partially rebuilt from 2012 to 2018 ; Among the 35 buildings erected are 15 reconstructed old town houses, including the Haus zur Goldenen Waage , the New Red House and the Rebstock and Goldenes Lammchen courtyards . At the end of September 2018, the "New Frankfurt Old Town" was opened with a three-day festival.

In Holzgraben , a southern parallel street to the Zeil , the two houses Holzgraben 9 and 11 are the last remaining war ruins in the city center. Only the ground floor is left of both houses. They are located exactly opposite the former Wronker department store (Holzgraben 6-10), of which remains of the rear facade are still preserved.

Commemoration

In 1955, Mayor Kolb ordered an annual mourning flag from March 20 to 23 to commemorate the destruction of Frankfurt. On May 28, 1973 the magistrate decided:

“On the occasion of the 30th return of the destruction of Frankfurt's old town in 1974, a commemorative plaque is to be created, which is to be placed in the ground in the area between the cathedral and the Römerberg. At the same time, an exhibition is to be held in the Historical Museum on the development of Frankfurt's old town up to its destruction and then its reconstruction and the destruction of Frankfurt in the last war. The order to flag the mourning on the occasion of the destruction of Frankfurt's old town in the period from March 20 to 22 each year is canceled. "

The reason for this stated that “another worthy form of commemoration should be sought, because a memory should not be lost due to the growing up of a new generation, but what happened at that time should be illustrated differently than it has been up to now. In view of the general foreign policy aimed at maintaining peace, it no longer seems sensible to us, almost three decades after the end of the Second World War, to still point out the - surely useless - destruction of Frankfurt's old town by an annual mourning flag [...] This in the pavement A commemorative plaque, unlike a flag, would only permanently and permanently remind the citizens and many tourists of the destruction of Frankfurt's old town and the destruction of large parts of Frankfurt in the last world war for only a few days. "

On March 22, 1978, Mayor Walter Wallmann unveiled the memorial plaque, a bronze plate set into the floor, in the pedestrian zone in front of the Technical City Hall . It was designed by the Frankfurt sculptor and lecturer at the Städelschule Willi Schmidt and bears the label

“1939 In memory of 1945. Between June 4, 1940 and March 24, 1945, Frankfurt was hit by 33 air raids, countless disruptive flights and low-level aircraft attacks. Thousands of tons of high explosive and incendiary bombs destroyed or damaged four fifths of all structures. On March 22, 1944, a major attack completely wiped out the old town. At the end of the war, 17 million m³ of rubble covered the city, which mourned 14,701 dead and 5,559 bomb victims. "

Above the inscription you can see a sketched row of houses, in the middle of which the Frankfurt Cathedral Tower rises up, surrounded by stylized flames.

The commemorative plaque was put into storage when the Technical City Hall was torn down. After completion of the Dom-Römer project, it is to be relocated in front of the reconstructed Golden Scales by 2020 as part of the redesign of the Domplatz . The intended place can already be seen in the pavement.

From 2010 to 2014, by resolution of the city council, every year on March 22nd at 8:45 p.m., almost all inner-city churches were ringed to invite people to an ecumenical memorial service at 9 p.m. in the Katharinenkirche.

From October 4, 2013, the 70th anniversary of the first heavy bombing of Frankfurt, to March 23, 2014, the exhibition Heimat / Front was on view at the Institute for Urban History .

Further memories of the destruction can be seen in several places in the urban area. In the rebuilt Katharinenkirche, a glass window created by Charles Crodel in 1954 shows Job's story of suffering , including the dial of the clock that had stopped at the time of the attack. On the north facade of the salt house, which was rebuilt in 1952, there is a three-story glass mosaic by Wilhelm Geißler facing Braubachstrasse . It shows a phoenix rising from the ashes , but can also be interpreted as a Frankfurt eagle rising from the ruins.

literature

- Hartwig Beseler, Niels Gutschow: The Fate of German Architecture at War - Loss, Damage, Reconstruction. Volume 2: South . Karl Wachholtz Verlag, Neumünster 1988, ISBN 3-529-02685-9 , pp. 799-831.

- Evelyn Hils-Brockhoff , Tobias Picard: Frankfurt am Main in the bombing war - March 1944. Wartberg Verlag, Gudensberg-Gleichen 2004, ISBN 3-8313-1338-5 .

- Michael Fleiter (Ed.): Heimat / Front. Frankfurt am Main in the air war. Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2013, ISBN 978-3-95542-062-8 . Catalog of the exhibition of the same name in 2013 at the Institute for Urban History , Frankfurt am Main.

- Karl Krämer, Gerhard Beier: Christmas trees over Frankfurt 1943 . Gutenberg Book Guild, Frankfurt am Main 1983, ISBN 3-7632-2842-X .

- Armin Schmid: Frankfurt in a firestorm. The history of the city in World War II . Verlag Frankfurter Bücher, Frankfurt am Main 1965.

- How Frankfurt was destroyed in the air war . Town Frankfurt am Main. Information from the press and information office. Frankfurt, March 1992.

Web links

- Air raids on Frankfurt am Main. altfrankfurt.com

- frankfurt1933-1945.de - Documentation on the air raids on Frankfurt am Main under Articles → War and Destruction

- Tobias Picard: Frankfurt am Main in the air war , in: historicum.net

- aufbau-ffm.de - Documentation on the post-war period in Frankfurt am Main ( Memento from December 26, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ^ Jürgen Steen, Historisches Museum Frankfurt : List of air raids on Frankfurt am Main in World War II. Institute for Urban History , September 30, 2003, accessed on May 22, 2019 . This list was compiled by the Frankfurt Police Headquarters in July 1945 at the request of the American military government . In addition, there were 18 low-flying attacks between August 10, 1944 and March 24, 1945. See also bombing raids on Frankfurt 1940–1945. Destruction. January 24, 2005, archived from the original on December 16, 2013 ; Retrieved July 29, 2014 .

- ^ A b Tobias Picard: Frankfurt am Main in the air war. March 28, 2006, accessed December 10, 2018 .

- ^ Frolinde Balser : From rubble to a European center: History of the city of Frankfurt am Main 1945–1989 . Ed .: Frankfurter Historical Commission (= publications of the Frankfurt Historical Commission . Volume XX ). Jan Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1995, ISBN 3-7995-1210-1 , p. 56 .

- ^ Frankfurter Neue Presse: Air raids on Frankfurt: 75 years ago: When the bombing war began | Frankfurter Neue Presse . ( fnp.de [accessed on September 8, 2017]).

- ^ Jürgen Steen, Historisches Museum Frankfurt : Air war damage as a sensation. Institute for Urban History , September 30, 2003, accessed on May 22, 2019 .

- ↑ Lutz Becht: “Judenwohnungen” - Racist Crisis Management in Air Warfare , in: Michael Fleiter (Ed.): Heimat / Front. Frankfurt am Main in the air war. Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2013, ISBN 978-3-95542-062-8 . P. 175

- ^ A b Monica Kingreen: Forcibly abducted from Frankfurt. The deportations of the Jews in 1941–1945. In this. (Ed.): After the Kristallnacht. Jewish life and anti-Jewish politics in Frankfurt am Main 1938–1945. (Series of publications by the Fritz Bauer Institute, Vol. 17). Frankfurt am Main 1999, pp. 357-402.

- ^ Ernst Karpf, Jewish Museum Frankfurt : Deportations of Jews from October 1941 to June 1942. Institute for City History , October 15, 2015, accessed on May 22, 2019 .

- ↑ Jürgen Steen, Historisches Museum Frankfurt : Luftalarme im Riederwald 1941. Institute for Urban History , September 30, 2003, accessed on May 22, 2019 .

- ↑ Andreas Hansert: "Jewish furniture" for bombed out , in: Michael Fleiter (Ed.): Heimat / Front. Frankfurt am Main in the air war. Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2013, ISBN 978-3-95542-062-8 . P. 164

- ^ Evelyn Hils-Brockhoff, Tobias Picard: Frankfurt am Main in the bombing war. March 1944 , Wartburg-Verlag, Gudensberg-Gleichen 2004, ISBN 3-8313-1338-5 , p. 27.

- ↑ Jürgen Steen: Rescue of people buried after the attack on April 11, 1943. Institute for City History , September 30, 2003, accessed on May 22, 2019 .

- ^ A b Royal Air Force Bomber Command, Campaign Diary October 1943. In: Official RAF Website. April 6, 2005, archived from the original on May 10, 2005 ; Retrieved December 18, 2013 .

- ^ Lutz Becht, Institute for City History ; Ernst Karpf, Monica Kingreen, Fritz Bauer Institute ; Michael Lenarz, Jewish Museum Frankfurt : An air mine hits the air raid shelter of the children's hospital in Gagernstrasse. Institute for Urban History , October 5, 2006, accessed on May 22, 2019 .

- ↑ Jürgen Steen, Institute for Urban History : The first major attack on Frankfurt am Main on October 4, 1943. Institute for Urban History , September 30, 2003, accessed on May 22, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Georg Struckmeier: On the dying of the Paulskirche. In: Frankfurter Kirchliches Jahrbuch 1955 , p. 136ff.

- ^ Stefan Geck: Dulag Luft / Evaluation Point West. Air Force interrogation camp for Western Allied prisoners of war in World War II. (European university publications series III: History and its auxiliary sciences, Vol. 1057). Frankfurt am Main 2008.

- ↑ a b Stefan Geck: The Frankfurt Dulag air in the bombing war: prisoners of war as human shields. Institute for Urban History , February 1, 2010, accessed on October 27, 2019 .

- ^ Royal Air Force Bomber Command, Campaign Diary December 1943. In: Official RAF Website. April 6, 2005, archived from the original on May 10, 2005 ; Retrieved December 18, 2013 .

- ↑ James S. Corum, The American bomb offensive against Frankfurt am Main 1943–1945 , in: Michael Fleiter (Ed.): Heimat / Front. Frankfurt am Main in the air war. Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2013, ISBN 978-3-95542-062-8 . Pp. 289-303

- ^ Richard G. Davis, Bombing the European Axis Powers. A Histocial Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive, 1939–1945 , Air University Press, Maxwell AFB, April 2006, p. 270 ( digitized version )

- ^ Armin Schmid: Frankfurt in the firestorm. The history of the city in World War II . Verlag Frankfurter Bücher, Frankfurt am Main 1965, pp. 84–86.

- ↑ Franz-Josef Sehr : 75 years ago in Obertiefenbach: The arrival of the expellees after the Second World War . In: The district committee of the Limburg-Weilburg district (ed.): Yearbook for the Limburg-Weilburg district 2021 . Limburg 2020, ISBN 3-927006-58-0 , p. 125-129 .

- ^ Jürgen Steen, Historisches Museum Frankfurt : The air raid on the main factory of Hartmann & Braun. Institute for Urban History , October 5, 2006, accessed on May 22, 2019 .

- ^ E. Hils-Brockhoff, T. Picard: Frankfurt am Main in the bombing war - March 1944. 2004, p. 37.

- ^ A b Royal Air Force Bomber Command, Campaign Diary March 1944. In: Official RAF Website. April 6, 2005, archived from the original on May 10, 2005 ; Retrieved December 18, 2013 .

- ^ AC Grayling: The Dead Cities: Were Allied Bombing War Crimes? P. 373. Munich 2009.

- ^ E. Hils-Brockhoff, T. Picard: Frankfurt am Main in the bombing war - March 1944. 2004, p. 40.

- ^ E. Hils-Brockhoff, T. Picard: Frankfurt am Main in the bombing war - March 1944. 2004, p. 41.

- ^ Georg Hartmann , Fried Lübbecke : Alt-Frankfurt. A legacy. Verlag Sauer and Auvermann KG, Glashütten / Taunus 1971, p. 330.

- ^ AC Grayling: The Dead Cities: Were Allied Bombing War Crimes? P. 374. Munich 2009.

- ^ Jürgen Steen, Historical Museum Frankfurt : Dying in the Bockenheimer Bunker. Institute for Urban History , August 29, 2005, accessed on May 22, 2019 .

- ^ RG Davis, Bombing the European Axis Powers, pp. 562 and 570.

- ↑ Manfred Gerner , half-timbered in Frankfurt am Main . Frankfurter Sparkasse from 1822 (Polytechnische Gesellschaft) (Ed.), Verlag Waldemar Kramer, Frankfurt am Main 1979, ISBN 3-7829-0217-3

- ^ Stefan Schlagenhaufer: 1st dud atlas for Frankfurt. There are still bombs everywhere here. November 9, 2009, accessed December 18, 2013 .

- ↑ Katharina Iskandar: Third find in four weeks. World War Bomb will be defused Monday. May 23, 2013. Retrieved December 18, 2013 .

- ↑ Air bomb turns out to be a dud. January 8, 2017. Retrieved January 23, 2017 .

- ↑ The largest evacuation of the post-war period comes to an end. Zeit Online, September 3, 2017, accessed September 4, 2017

- ↑ What to do with those infected with corona during the bomb disposal? In: FAZ.net. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, December 5, 2020, accessed on December 5, 2020 .

- ^ Matthias Trautsch: World War Bomb will be blown on Wednesday. In: FAZ.net. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, May 19, 2021, accessed on May 19, 2021 .

- ^ Fritz Lerner: Frankfurt am Main and his economy , Ammelburg-Verlag 1958. See also Trümmer-Verwertungs GmbH. In: Frankfurt is building. Archived from the original on September 6, 2013 ; Retrieved July 29, 2014 .

- ↑ Hans Riebsamen: Goethe House. The world was in pieces . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . August 27, 2009 ( online [accessed December 16, 2013]).

- ↑ F. Balser: From rubble to a European center. 1995, p. 62f.

- ↑ Over 250,000 visitors: Everyone wanted to go to the Altstadtfest at par.frankfurt.de , the former website of the City of Frankfurt am Main, accessed on October 3, 2018.

- ^ Frank Berger, Christian Setzepfandt : 101 non-locations in Frankfurt . Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISBN 978-3-7973-1248-8 , p. 86.

- ↑ Verbatim minutes of the 31st plenary session of the city council on Thursday, February 26, 2004, item 5 (28th question time). (PDF) The Lord Mayor's answer to question no. 879. March 22, 2004, p. 14 , accessed on December 18, 2013 .

- ↑ F. Balser: From rubble to a European center. 1995, p. 56.

- ↑ Photo of the memorial plaque

- ^ Minutes of the 7th meeting of the Dom-Römer Committee. (PDF) Item 4.3. October 5, 2017, p. 4 , accessed December 10, 2018 .

- ↑ Remembering the night of the bombing. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung No. 68 of March 22, 2010, p. 34.

- ↑ Accompanying volume: Michael Fleiter: HEIMAT / FRONT. Frankfurt am Main in the air war . Societäts-Verlag 2013, ISBN 978-3-95542-062-8 .

- ^ Reprint of the two volumes at Panorama Wiesbaden, 2000, ISBN 978-3-926642-22-6 .