Schopenhauerhaus

( rendering from the virtual old town model Frankfurt am Main by Jörg Ott )

( chromolithography , 1904)

The Schopenhauer house with the address Nice view 16 was a classicist house in Fischerfeldstraße quarter of today's city of Frankfurt am Main . To the north it had, interrupted by an inner courtyard, which was spacious by the standards of the old town , a rear building facing the street Hinter der Schöne Aussicht at number 21.

The building was constructed in 1805 for the Jewish banker Wolf Zacharias Wertheimber according to plans by the city architect Johann Georg Christian Hess and is considered the main work of bourgeois classicism in Frankfurt. In addition to its architectural and art-historical significance, it served as the home of important urban and national personalities in the 19th and first half of the 20th century. It was named after the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer , who lived there from 1859 until his death in 1860. It was the last of his many residences .

During the Second World War , the Schopenhauerhaus, after having suffered only minor damage from several heavy bombings , caught fire in the bombing raids of March 22, 1944 and burned down to the ground floor. After the war, a functional building in the style of the 1950s was built on the plot, which is now a corner house due to the breakthrough in Kurt-Schumacher-Straße . Nothing reminds of its famous predecessor building.

history

History and development of the building site

( copper engraving by Matthäus Merian the Elder with addenda by the heirs)

The valley on the Main , east of the cathedral hill , was already known as the fishing field in the Middle Ages . However, a dense development like in the rest of the city area made the weather conditions hardly possible: During the autumn and winter months the swelling river flooded the area and turned it into a swamp, in winter it often froze over. Nevertheless, a small suburb developed there , which became the permanent residence mainly of the fishermen who gave it its name , but also of white tanners .

The Frankfurt chronicler Baldemar von Petterweil described the settlement around 1350 as a single row of houses separated by three small streets. However, the village, with 29 residents in 1354 and 22 in 1365, went under again at the end of the 14th century. Presumably, the reconstruction of the Old Bridge by Madern Gerthener at the time led to narrower arches than before, which made the bridge now act like a barrage and press the water even more into the area. Strategic-military reasons against the background of the Hussite Wars at the time were also considered by research as a reason for the task.

Both the city wall of the Staufer period and that of the second city expansion after 1333 had left the area free. Instead, it was protected by its own walling, which, however, could hardly do anything against the annual floods. It was not until the bastion fortification of the 17th century that it was strengthened and raised towards the Main, and the area was included in the urban area in 1632/33 by means of the Fischerfeld bulwark. However, as it has been since the suburb's decline, the inner area remained largely undeveloped.

( drawing by Johann Kaspar Zehender )

However, the fishing field was used as a shooting range for the shooting club of the Krautschützen , whose shooting range had been one of the few permanent structures since the third quarter of the 15th century; their targets were oversized on the Merian maps of the city. Later there were gardens and the now tall old trees, the only larger recreational area within the protective walls. In the 16th book of Poetry and Truth , Johann Wolfgang von Goethe reported how he liked to skate here in winter. Since the time of the Reformation , prostitution, which was no longer tolerated in the city, has shifted to that remote east of the city , especially during masses .

In Goethe's time, the long peace in the 18th century, the rise of the bourgeoisie , the Enlightenment and the advance of classicism had led to a fundamental change in ideas about life and living in large parts of the population. With palais-like buildings on the Zeil and Roßmarkt , the only extensive streets and squares, as well as garden houses in front of the city walls, the longing of the urban upper class in particular for more generosity in construction was expressed. The most striking feature was the conversion of the bastionary fortifications of the city, which, because of their military insignificance compared to modern firearms, had been planted with trees since 1765 and served as a pleasure avenue for walks.

( old colored copper engraving by Jakob Samuel Walwert based on a model by Johann Hochester )

But even in the Neustadt, today's inner city , there was no building site for the realization of projects according to the new ideals, but with a few exceptions, narrow medieval streets and small parcels , whose merging for many reasons, but primarily because of complicated ownership, hardly dominated was possible. At the end of the 1780s, the city council came up with the idea of expanding the city for the first time since the early 14th century. Perhaps as early as 1788, but certainly in 1792, the city architect Johann Georg Christian Hess , who has been in office since 1787, presented a first development plan for the future quarter. The execution was decided by the council in 1792 and the auction of the land was initiated in April.

The work began in 1793 and progressed systematically from west to east due to the desired closed perimeter block development. On the east side of the Fahrgasse , the Brückhof and a number of the gabled houses that dominate there were demolished in order to create a connection to the new building area. The beginning of the subsequent filling of the fishing field up to the top of the Gothic city wall, now the lining wall for the quay , cannot be clearly dated. It is only clear that in the swampy area, excluding the recessed basement areas, it was sometimes over six meters.

Further engineering details of the enormous undertaking at the time, for example the procurement and logistical management of the 480,000 cubic meters of filler material that resulted from around 400 meters of bank length and 200 meters of depth in the district, are unknown. All that has been handed down is that the embankment dragged on much longer than expected and was only completed well after 1810, probably not until around 1820, which indicates the difficulties. The oldest buildings in the area of the former Brückhof, which followed quickly after the filling, dated to the year 1797, the last were built after an apparently longer interruption in a major final construction phase in the early 1820s. With the inauguration of the Old City Library in 1825, the city expansion was considered complete.

The client and his origin

The Frankfurt Jews , who originally resided south of the cathedral with almost equal rights , were forcibly resettled in a ghetto in front of the Hohenstaufen city wall in 1462 . The Frankfurt Judengasse adjoined the Fischerfeld to the south . Two major fires in 1711 and 1721 destroyed large parts of the Judengasse, but each time they were rebuilt in their old form. This means that around 200 houses with front widths of two to rarely more than four meters squeezed into 330 meters of lane length. More than 3,000 people lived here under these conditions.

In 1769 Zacharias Isaak Wertheimber from Munich married Frummet Speyer , a sister of Isaak Michael Speyer, who was born here in the Judengasse wedding house . Before the rise of the Rothschild banking house, he was by far the wealthiest Frankfurt Jew. Zacharias Isaak, who soon settled in the ghetto with his brother Elias Isaak , where he also did banking, came from an important family. Both were great-grandson of in Vienna as imperial court factor and Chief Rabbi make Samson Wertheimber . An example of his influence may be that after the street fire of 1711, against the will of the Frankfurt Council, he was able to enforce the construction of a luxurious, ten-meter-wide stone house through direct imperial intervention.

The banking business of the brothers under the company name Zacharias & Elias Isaak Wertheimber developed splendidly, as traditional information about their assets shows. When Elias Isaak died in 1794, he left behind a private fortune of 90,000 guilders , Zacharias Isaak succeeded him in 1803. Wolf Zacharias, born in 1782, ran his father's company from his eight children . On December 15, 1803, he married a fifteen-year-old daughter of his late uncle Elias Isaak Wertheimber, Leonore , with whom he had at least 15 children.

(colored aquatint by Christian Georg Schütz the Younger and Regina C. Carey )

In 1796, when the city was occupied by Austrian troops, it was shelled by French besiegers, whereby the Judengasse caught fire again and lost around a third of its houses. The Wertheimbers' headquarters, the Roter Turm house , which had a facade width of only 2.28 meters, burned down.

After the French Revolution and the beginning of the French occupation of the city, the Jews at least temporarily overcame the ghetto obligation and obtained permission to settle in the Christian part of the city. The beginning of emancipation was also evident in the newly built houses in the northern part of Judengasse. Instead of the roughly 60–70 destroyed buildings, around 20 classicist new buildings were built on the same area.

Even before the prince-prince Carl Theodor von Dalberg, who was appointed at the instigation of Napoleon in 1806 , decreed the equality of all denominations and this was enforced by ordinance in 1811 against payment of 440,000 guilders by the Jews, some very wealthy Jewish citizens managed to buy building sites in the Fischerfeld. Presumably they also had to pay high sums for the right to build a house there, but this has not been recorded. Wolf Zacharias Wertheimber bought two parcels on the Schöne Aussicht , in contrast to the majority of his fellow believers, who preferred to settle on Brückhofstrasse and Fischerfeldstrasse .

The architect and the construction work

( copper engraving )

For Johann Georg Christian Hess , the ideals of the 18th century were still decisive when drawing up the development plan, which provided for a regular network of streets running parallel and intersecting at right angles. Deviating from this and more progressive, on the other hand, was the renunciation of a wide thoroughfare in favor of largely equal rights for all roads. The generous cut of the almost equally large parcels, which allowed an average of 15 to 16 meters facade width with almost twice the depth, also pointed to the future.

An absolute novelty and a complete break with the previous building policy was the prerequisite for designating the "new facility" as a purely quiet residential area; the settlement of handicraft businesses was forbidden, as was the posting of signs on the houses to be built. It was no less revolutionary to only build apartment buildings of the same shape and height there that were to be rented out. Hess was probably able to deal extensively with the model for this concept during his studies in Paris 1774–1776.

( old colored copper engraving by Johann Conrad Felsing based on a template by Christian Friedrich Ulrich )

Wolf Zacharias Wertheimber had acquired two parcels because he wanted to build a house with a facade width of 40 meters. If you consider the large number of children in the family and the dimensions of the previous house in the Judengasse, this generosity was understandable. Nevertheless, his intentions, which were contrary to the ideals of the quarter, could in principle be considered a risk; In addition, Hess, who as head of the building department had complete control of the urban construction industry of the time, had the reputation of a dogmatist . He subjected even the smallest details of his buildings to the teachings of great models of the Classical period such as Vitruvius or Palladio .

But the client probably knew the other side of the city builder, which has only reappeared in recent research. Hess himself took part in the property speculation so intensively that he had to be called to reason several times by his own office . In order to maximize profit, he often violated the building regulations he had issued himself when, as is not uncommon, he acted as a private building contractor. As an architect of a classical school he was so overwhelmed with the urban planning task that from 1802 he was assigned the geometer and mint master Johann Georg Bunsen . This should probably also play the role of a monitoring authority.

In Wertheimber's case, perhaps the most striking example of this, Hess defied his own standards and had master mason Kayser erect an extra-wide building in 1805 using one and a half parcels. Despite the compromise, it was the widest, tallest and deepest in the whole of Fischerfeld and could even compete with the buildings of the high nobility on the Zeil . The cost estimate for the later Schopenhauerhaus was 180,000 guilders, an enormous sum for the time, but which, as a millionaire in guilder, should hardly have caused difficulties for the client.

From the beautiful view 16 to the Schopenhauerhaus

( old colored copper engraving based on a template by Johann Friedrich Morgenstern )

In the period after 1800, the exchange and exchange business was affected by the coalition wars and the continental blockade. Anyone who wanted to earn money as they did in the past soon had to take high risks. Probably because of this, Wolf Zacharias Wertheimber also acted as the private financier of Napoleon Bonaparte , whose rise initially lifted him up. Shortly before the Russian campaign , he is said to have visited him personally at the Schöne Aussicht and adored his wife a marquise ring.

But with Napoleon's defeat in the East and the fall in Paris , Wertheimber lost his entire fortune practically overnight, his wife never overcame the trauma. Until old age, she was said to have stood at a window on the ground floor every day, waiting for a courier from the French capital with her husband's news that Napoleon had won. But after the belated return from Paris Wertheimber managed to save the house and the company from bankruptcy . He himself moved back to the tiny house JQ 131 in Judengasse , where he lived until his death in 1844 and, according to tradition, regularly swept the street to calm his nerves.

The family's residence at Schönen Aussicht was thus retained. At the time of the Free City of Frankfurt , Wertheimber's wife lived there, his son Zacharias Wolf , born in 1809 , who worked as a stockbroker , daughter Sara born in 1811 , the youngest son named Leopold, born in 1827, and a few servants. The remaining rooms in the house had probably been divided into rental apartments due to financial needs. In 1856 the most important - since she was the only one who wrote her memoirs in writing besides Fried Lübbecke - moved in here - the then seven-year-old Lucia Franz . She was the fifth child of her parents, who came from Frankfurt, and her father was a trader. It was there that she saw the move in and death of the man who later gave the building Schöne Aussicht 16 its name.

Arthur Schopenhauer first visited Frankfurt am Main when a cholera epidemic broke out in Berlin in 1831, which was considered healthy and "cholera-proof". His first apartment was at Alte Schlesingergasse 16/18, today in the middle of the banking district . When he fell ill in the winter of 1831/32, despite the good reputation of the city, he moved to Mannheim in July 1832 and returned to Frankfurt again in July 1833, this time for good .

After moving numerous apartments, Schopenhauer finally found himself in March 1843 at Schönen Aussicht 17, that is, in the neighboring house to the west of the magnificent Wertheimberber building. Narrated is his special because of his deafness description of residence for visitors - " parterre , ring right, glass door, strong." . In the years that followed, this was not only where his last major work, Parerga and Paralipomena , was created, but he also witnessed the September unrest in Frankfurt in 1848, in which almost 100 people died.

In the summer of 1859 there was a dispute with his landlord - allegedly because of his poodle, Atman - as a result of which he and his housekeeper Margarete Schnepp moved one house number further and rented a room with the Wertheimbers, also on the right-hand floor. Although Schopenhauer as misanthrope and eccentric was disreputable, to Lucia Franz became friends with him and especially his dog quickly. In this way, she was able to draw a true picture of his meticulously planned daily routine, probably following the example of Immanuel Kant , and his poor to chaotic living conditions on the other.

First she described the high level of dressage that Schopenhauer Atman had given. With a basket in his mouth, in which his master put money, he went shopping for him on orders in two shops in the nearby Fahrgasse and in a bakery in the neighboring Große Fischergasse . Otherwise he was treated like a servant, the housekeeper cooked for him and dined with him at a lunch table. She regularly sheared the poodle and knitted clothes and stockings from its wool.

Schopenhauer's day-to-day business always included a visit to the Englischer Hof at Roßmarkt - the building built in 1797 by Nicolas Alexandre Salins de Montfort was one of the most important inns in the city at the time - from which he returned at three o'clock sharp in the afternoon. There Schopenhauer had just as few friends there because of his mocking manner, which was the source of countless anecdotes that were not always correctly passed down , as he did among the servants, who locked him up at least once in the only toilet at Schöne Aussicht.

Franz described Schopenhauer's apartment as follows:

“Schopenhauer's apartment consisted of four rooms and a kitchen. The middle room at the front was his living room, on the left was his bedroom, on the right the single-window was his library. In the kitchen, which he never used, there were boxes of books and papers. In the back the housekeeper had her room and a small ship's stove on which she cooked meals for herself and the poodle. […] Its establishment was very simple, almost poor to call it. There was almost no seat at his place, as there were books and notebooks on the sofa and chairs, on the table and desk. […] In his library it always looked quite mixed up. Often times, when he couldn't find a book, he would tear everything off the shelves and throw it on the ground. [...] In the corner there was a camp bed with a gray blanket, behind it was a green curtain. "

After a cough that started in autumn 1860, for which Franz bought him “ Schillertränen ” (lollipops) on Mainkai , he soon became bedridden and died on September 21, 1860, according to the obituary of September 23, of paralysis . The funeral procession from the house where he died via Fahrgasse to the main cemetery was very small, in line with its low popularity, even if Franz repeatedly emphasized in her memoirs how her father and her teachers at the grammar school had repeatedly emphasized that only subsequent generations would understand and understand his work would appreciate.

After Fried Lübbecke, Schöne Aussicht 16 has been called Schopenhauerhaus since then . However, the lack of attention given to the Fischerfeldviertel , which like the old town sank to a poor quarter in the second half of the 19th century, makes this appear doubtful, also because of the lack of literary tradition. In the Frankfurt address book from 1916, the previous house, i.e. Schöne Aussicht 17, is referred to as the Schopenhauerhaus. So there is some evidence that Lübbecke coined the term for the number 16, which is still common today.

From Schopenhauerhaus to wine shop with famous tenants

(photography by Carl Friedrich Mylius )

The spacious cellars of the houses in the Fischerfeldviertel, which were already planned as modern engineering structures , have been ideal wine storage facilities since they were built . When Lucia Franz 's father died in 1865, the Koblenz wine merchant Moritz Sachs senior acquired Schöne Aussicht 16 from the Wertheimbers . In 1868, the son Moritz Sachs junior , who had just reached the age of majority, opened the Sachs & Höchheimer wine store there with a business partner . The approximately 2.50 meter high cellar of the house, which extended under the entire parcel, had a capacity of around eighty barrels with a total of around 70,000 to 80,000 liters of wine , liqueur and brandy .

After the house was sold, the remaining family members, except for the widow Leonore Wertheimber, apparently no longer kept it in the city. The latter died very old at the age of 83 in the Schopenhauerhaus , as indicated by an inscription carved into a window on the third floor until it was destroyed:

"Tonight my dearly beloved mother Leonore Wertheimber, née Wertheimber, died in this room on February 20, 1872."

Since Leopold died in Berlin in 1872 - when exactly he left the city cannot be found out - only Zacharias Wolf is actually the only person who could write the message . Only after his mother's death on October 4, 1871, at the age of 62, did he marry Judith Dusmus , who was only 27 years old , in Leeuwarden , where the male line of Wolf Zacharias Wertheimber also died out on October 13, 1883 . Another great-grandchildren, Samson Wertheimbers , who immigrated to Frankfurt am Main in the 19th century - the details are unknown - did not survive the National Socialist era .

Although its new owners kept the rental apartments at least on the upper floors, the former family residence remained the main building of the Sachs family throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. The company's founder set up his office in Schopenhauer's former apartment on the ground floor, and they lived on the second floor Parents. After her death, he moved into their apartment with his wife, from whom he apparently adopted the name Fuld . From this marriage a daughter, Rosie , was born. She lived there since 1912 with her husband, the architect Ernst Hiller . However, the remaining, generously proportioned rooms were still rented according to the Wertheimbers' model.

( drawing by Peter Becker )

The first of the illustrious guests and tenants of the Schopenhauerhaus in this epoch was the commanding general of the Austrian garrison of the Free City of Frankfurt , Bayer , from 1860 , whose daughter Anna Lucia Franz still met. Until the takeover of Prussia in 1866 he held every day at noon in the main floor of the first floor open panel. After 1866, the consul Hartmann-Coustol followed . The philologist and grammar school director Tycho Mommsen , brother of the historian Theodor Mommsen , moved into the third floor . From 1864 to 1886 he was director of the municipal grammar school , which since 1839 had its seat in the nearby Arnsburger Hof on Predigergasse .

( wood engraving )

In the 1870s, the Catholic historian Johannes Janssen moved into Mommsen's apartment; from 1854 to 1891 he taught history and the Catholic religion at the town high school. In his apartment he completed his major eight-volume work, The History of the German People Since the End of the Middle Ages , which sparked a controversial debate from the 1880s onwards. Under the influence of the Kulturkampf, Janssen had become a representative of ultramontane historiography and a resolute opponent of the Reformation . In his work he tried to prove that she was responsible for negative social, political and denominational developments in the 16th and 17th centuries. Protestant critics, in particular, turned against this , mostly overlooking the fact that his holistic social history, despite its tendentious evaluation, made significant contributions to the previously very one-sided reception of Luther .

The criticism that was brought to him by the wash basin in the Schopenhauerhaus and to which he devoted a large part of his energy was seen by contemporaries as the cause of his relatively early and sudden death on Christmas Eve of 1891. The Frankfurt painter Fritz Boehle captured the funeral procession that led him on December 27th from the house where he died at the Schöne Aussicht across the Fahrgasse to the main cemetery .

Shortly after Schopenhauer's death, the family of the customs officer Schadenlich lived in the former apartment of Schopenhauer . It is anecdotal that his wife turned 100 there and in 1917, after a tenancy of more than fifty years, asked the landlord to have the apartment re-wallpapered when the well-wishers were received. However, this refused, allegedly with reference to the fact that the previous wallpapers should be sufficient for the rest of her days, whereupon the very old woman terminated the tenancy and moved a few houses up the Main, where she died that same year.

The era of Fried Lübbecke

Also in 1917, the Frankfurt art historian Fried Lübbecke and his wife moved into the apartment on the third floor. At around the same time, the food chemists Reiss and Fritzmann rented a workshop in the former Schopenhauer apartment on the ground floor and the sculptor Richard Petraschke in the attic apartment. The latter was well lit by the huge dwarf house , which also had a counterpart on the back, and was ideal for a studio . Nevertheless, according to Lübbecke, the rents were extremely modest as the building was on the edge of the then insignificant and unrenovated old town . This went hand in hand with its reputation as a haven for crime and prostitution .

Lübbecke recognized in the old town an independent complex with a high historical and art historical value, largely preserved from the rest of the urban development. In 1922 he founded the Association of Active Old Town Friends , which set itself the task of maintaining and repairing Frankfurt's old town. From the middle of the decade, the federal government restored numerous houses in the old town, mostly only externally, and brought the medieval ensemble in the heart of Frankfurt back into the general awareness through numerous publications, for which Lübbecke was able to win over Leica photographer Paul Wolff .

As early as 1923 the association had acquired the important Gothic patrician house Fürsteneck on Fahrgasse and had it renovated, which from 1934 also served as the association's headquarters. For Lübbecke himself, this was a stroke of luck, as the house was only a few steps away from the beautiful view . He wrote:

“Wasn't the contrast unbearable? How can you work in a Gothic castle and live in a classicist house without judging one or the other! They were only different on the outside, but on the inside they were one. [...] Just as furniture from different epochs can get along very well in an apartment if it is in good shape and craftsmanship, so on Fahrgasse Gothic and Classicist houses stood opposite each other without hostility, indeed complemented each other. If the stranger was tired of the frizzy wandering through the alleys around the Goethehaus, he relaxed on the quiet, wide streets around the Schopenhauerhaus, enjoyed the white fronts of the Schöne Aussicht or the Brückhofplatz around the Egyptian fountain. No intrusive noise, no advertising! Truly, this quarter was full of noble simplicity and quiet grandeur. "

Shortly after the First World War , Ernst Hiller's proposals to convert the Schopenhauerhaus and divide it into small apartments were allegedly rejected by the owner Moritz Sachs-Fuld on the grounds that one should not disturb the spirits of music living in it. In fact, according to Lübbecke's memoirs, numerous musicians, especially the composer Paul Hindemith , who lives in the Kuhhirtenturm on the other side of the Main and who is his friend , regularly visited the Schopenhauerhaus. With him came artists, patrons and intellectuals such as Alfredo Casella , Darius Milhaud , Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge , Ludwig Rottenberg , Hermann Scherchen , Julius Meier-Graefe , Edwin Redslob , Cornelius Gurlitt , Georg Swarzenski , Benno Elkan and Reinhard Piper .

This era came to an end with the penetration of National Socialism into the public and thus also the intellectual and cultural life of the city. In 1935, when Ernst Hiller also died six years after the death of his wife in the Schopenhauerhaus, an open confrontation broke out between the National Socialist People's Welfare Association (NSV) and Fried Lübbecke. The point of contention was the old town children's home of the Association of Active Old Town Friends , which had been in existence since 1924 and was located on the meadows in southern Main East of the Sachsenhausen old town , today the site of the Deutschherrnviertel . For four weeks all year round, it served 40 children from the poorest households in the old town free of charge as a playground, food and health care. Now it was supposed to be separated from the association and integrated into the National Socialist organizational structures.

Although Fried Lübbecke was able to rely on the sympathy of the National Socialist Lord Mayor Friedrich Krebs , he was apparently powerless or unwilling to offer resistance in the matter. When the chairman of the Altstadtbund refused to hand it over, on the evening of May 7, 1935, SA men in civilian clothes moved out, stood in front of the Schopenhauerhaus and asked the “traitor Lübbecke” to come out in a chorus . However, he and his wife managed to escape through the narrow streets of the old town and, with the help of some friends, leave the city. The SA men then let out their anger at the Schopenhauerhaus and the Fürsteneck club headquarters, which were smeared with slogans and ransacked. Almost all of the Frankfurt daily newspapers reported on the next day in inflammatory articles about the "unsocial union" with the "enemy of the people" at its head.

After a few days in “exile” in Bonn, Lübbecke and his wife received a telegram from the Lord Mayor with the content: “Please return. Everything well done. Cancer. ” However, the second chairman of the Old Town Association, Max Fleischer , in Lübbecke's absence felt compelled to rent the children's home to the NSV for the symbolic amount of five Reichsmarks per year. When the contract expired after a year, the home was, according to Lübbecke, completely looted and neglected. So he agreed to the SS proposal to demolish the home and rebuild it on the other bank of the Main as a "comradeship home". Even that didn't happen, as the building materials piled up there disappeared within a few days and were probably used as firewood.

After the Nuremberg Laws came into force, both the permanent guests and the residents of the Schopenhauerhaus disappeared more and more. The majority went into exile overseas, others, such as the Social Democratic deputies and editor at the Frankfurter Volkszeitung , Stephan Heise , came to the extermination camps , he as well over 10,000 predominantly Jewish citizens of the city did not survive. Richard Petraschke died a natural but unexpected death in 1937 after having had his studio in the attic for over two decades. The sculptor Herbert Garbe moved into his workplace .

Three and a half years after the riots around the old town children's home, the Schopenhauerhaus was again devastated during the Reichspogromnacht . The mob used crowbars to smash the precious furnishings on the ground floor with the bust of Schopenhauer, which had been there since 1930, as well as the bottle store in the cellar, where the French cognac was standing knee-high the next day . In addition to the inventory books that have been kept in full since the establishment of the wine store in the house, the pictures of the children of the Weiß family who died in World War I and who have been running the business of Sachs & Höchheimer under their own name since the beginning of the 20th century were burned or torn to shreds .

At the beginning of 1939 the elderly Moritz Sachs-Fuld offered the house to the city for use as a Schopenhauer Museum. There were already plans for this before the First World War. The late offer by the owner is likely to be seen in connection with the fact that the only male heir in question, the grandson Hans Sachs-Hiller , had committed suicide in 1938. The National Socialist city administration, however, no longer responded: With a contract dated April 3 of the same year - admittedly only under the repressive climate of the time - they acquired all of the city's Jewish property for 1.8 million Reichsmarks . This also included the Schopenhauerhaus. As a result, without further correspondence , she sent craftsmen to set up the museum in the house. Sachs-Fuld, who did not allow for any further quarrel, died there in 1940 at the age of over 90.

Downfall, Post War and Present

In the same year, Frankfurt am Main experienced the first air raids, which initially caused hardly any damage and spared the city center, which is so rich in cultural monuments. After the attacks on Lübeck , but above all on Cologne , it was clear that the largest city in what was then Hesse-Nassau could be the target of devastating attacks at any time, which is why from now on more facade developments of the entire old city center were created in the course of the so-called old town survey . The interior of certain buildings such as the Schopenhauerhaus was even documented in floor plans and sectional drawings, and as late as 1943 Paul Wolff captured a large part of the city's classicist building heritage, including almost the entire Fischerfeldviertel , in photographs.

In October of this year, the first heavy air raid hit the old town, causing severe devastation , especially in the northern part around Töngesgasse , but also causing irreversible damage to outstanding individual buildings such as the Großer Braunfels on the Liebfrauenberg or the Römer . An air mine exploding at the height of the cowherd's tower destroyed the windows of all the houses on the Schöne Aussicht , including the Schopenhauerhaus , but otherwise the classicist urban expansion remained largely undamaged.

The most serious attack to date occurred on January 29, 1944, which destroyed the Frankfurt city archives at the cathedral next to the screen house , one of the richest in Germany up to then. It lost large parts of its inventory. The Willemer-Dötschesche Haus (No. 9), the second largest building after the Schopenhauerhaus , was hit by three high-explosive bombs , which penetrated the cellar and completely destroyed it. All the people in the basement who thought they were safe in the massive vaults also lost their lives.

Another high-explosive bomb hit the Hochkai directly in front of the Schopenhauerhaus, tore a six-meter-deep hole and threw the almost two-meter-thick lining wall - actually the former Gothic city wall facing the Main - onto the Tiefkai. The cobblestones of the street broke through the roof like shrapnel , the pressure destroyed all the doors and the windows, which had only just been restored, but the substance of the house was once again intact. The building was saved again during the first of the three March attacks that destroyed the entire old town when it was possible to extinguish over twenty sources of fire in the roof and third floor caused by fire bombs .

What was overlooked, however, was that a smoldering fire spread through the breakthroughs in the fire walls of the neighboring house in the west, which had already burned down, and spread to the items of equipment stored in the basement. But the fire brigade was also able to bring this fire under control as one of the few of those days by pumping the basement full of Main water, which also destroyed the last remnants of the inventory located there. However, the long smoldering had burned the firewall in the foot so much that it slowly deviated from the perpendicular to the west and threatened to fall, which is why the proper evacuation of the building - that is, with the household being secured - was ordered.

The moving van came twelve hours late, however, because on the evening of March 22, 1944, the city was hit by the heaviest air raid of World War II . Fried Lübbecke wrote down the memories of the attack in Bad Homburg in April 1944 in his text Farewell to the Schopenhauer House, which is considered one of the most important contemporary documents about the destruction of the city. It is reproduced here in excerpts:

“On the detour over the Main Quay, we then hurried home and covered our dinner table for the last time by a candle. My wife is just pouring the first cup when the few sirens that have survived Saturday start to howl a rather pitiful pre-alarm. A view from the balcony shows many spotlights against a bright hazy night sky. A cascade of green and white sparks floats down, apparently straight towards our roof. At the same moment the first bombs crash without being heard whistling. We race down the stairs and just reach their hall on the first floor. A terrible explosion tears us down, throws windows and doors at us, buries us under rubble, mortar and dust as thick as a sandstorm. Bomb after bomb rushes down, probably for ten minutes. The huge house sways like a drunkard, through the window holes suffocating smoke comes with the dust, also flickering light. The Secret Annex is on fire. We hurry down the courtyard stairs to the air raid shelter! A look up: the dwelling is also on fire - the high studio with the three light arched windows [...] Already there is a crack. The second wave is coming. Again bomb after bomb in close proximity. The house bumps like a truck on a frozen country lane; the thick wall between the cellars collapses; Thousands of incendiary stick bombs rattle down, [...]

The second wave is over. I race up the stairs. Above me in the roof the fire is already howling - indelible even for a fire brigade. In other rooms too, the wall is already eating its way through the ceiling. I stand high up at the corridor window and look north, west and east over the city. Everything is on fire! [...]

The third wave is approaching. I calmly go down the stairs. The courtyard is full of rubble, the half-timbered gable, eaten up to the beam scaffolding, threatens to fall down at any moment and spill the last exit of the cellar. We all climb it, although bombs are still falling, […] We walk through the hallway. […]

In the middle of the [Old] bridge we stand under the cross of the bridge cock. We live. The fire is visibly eating its way through our apartment, from window to window, now descends the stairs, appears on the left at the first window of the second floor - quickly, quickly through, all windows are lit, throw long tongues of fire over the Main, whirl pillows, books, Carpets burning out. The heat is so intense that I take off my coat. A sky-high cloud of fire drifts over the roofs towards the Main, driven by the firestorm. Now the cathedral stands tall and free over the Main, over the old bridge. Nobody has seen him like this before. The tip disappears in billowing smoke. A sofa and a chair are next to us. Jahn and Diel dragged them out of Schopenhauer's apartment on the ground floor - Schopenhauer's death bed, Schopenhauer's desk chair - Parerga - Paralipomena. "

Despite the degree of destruction described and the amount of bombs dropped that evening, a few buildings on the Schöne Aussicht survived the Second World War unscathed. This was the case with house numbers 12 and 15, the direct eastern neighbor of the Schopenhauerhaus. Almost the entire facade of the rear building remained standing on the street Hinter der Schöne Aussicht .

When the Fischerfeldviertel was rebuilt, a little more consideration was given to the traditional city layout than in the rest of the old town. However, this can hardly be attributed to historical awareness, but rather to the fact that the quarter and the structure of the parcels largely met the requirements of the 1950s.

At least on the blocks facing the Main, the old block perimeter development was largely resumed while maintaining the street widths and even including the majority of the old basements. In the second row, however, in comparison to the historical existing buildings, immense large buildings such as the current building of the city planning office or the museum Judengasse characterize the picture. In addition, there is an increasing dissolution of the old structure in favor of open spaces used as parking lots, for example .

Also on the site of the former Schopenhauerhaus, a functional building typical of the time was built as a corner house in the early 1950s, as house numbers 17 and 18, which were once adjoining to the west, fell victim to the breakthrough in Kurt-Schumacher-Strasse . The undamaged house number 15 was, as can be seen from a comparison of photographs, demolished by around 1970 at the latest. A last remnant in the form of a window axis on the facade of the ground floor was evidence of it until 2010.

In February 2010 it became known that the FRANbesitz- & Verwaltungs-GmbH from Weiterstadt had received the building permit for a 54-room hotel on the parcels of the former buildings Schöne Aussicht 13-15. The architectural office commissioned with the development was SpaBau from Modautal . The hotel, which was originally to be named Schopenhauer-Hotel , opened as Hotel My Main in spring 2019 .

When the construction pit was excavated, the last remaining part of the former neighbor of the Schopenhauerhaus had also disappeared. Later, not only the remains of the classicist cellar came to light, but also the openings, now bricked up, described by Fried Lübbecke to the apparently preserved cellars of the neighboring houses, i.e. also to the cellar of the former Schopenhauerhaus adjoining to the west. After clearing the basement remains are encountered far older remains of walls that the monument of the City of built around 1200 Staufenmauer associates. A parallel wall that was also uncovered could be that of the second city expansion from 1333 . From the point of view of the office, “maintaining the walls and integrating them into the new building [...] was hardly possible and also not sensible” ; meanwhile they have been destroyed by further foundation work.

architecture

General

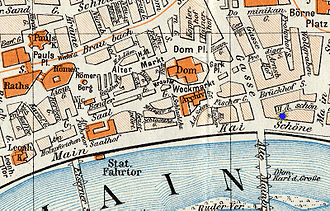

( chromolithography by Friedrich August Ravenstein )

As can be seen from the planning by Johann Georg Christian Hess (cf. story ), the Schöne Aussicht and the streets connecting to the north should run parallel and the cross streets at right angles to the bank of the Main . At the same time, however, the old town to the west, especially the Fahrgasse, had to be connected, which curved slightly to the west in relation to the new district. The transition was created by the fact that the westernmost parts of the streets parallel to the Main, namely Brückhofstrasse and Hinter der Schönen Aussicht (as a dead end), bend to the south and thus meet the tramline at almost right angles.

Any other route would have destroyed far more buildings, especially on the east side of the Fahrgasse and probably also the Arnsburger Hof on Predigerstrasse . This consideration of the old buildings, which was remarkable for the spirit of the time, even if it was primarily concerned with the expected resistance of the residents, however, resulted not in the desired rectangular , but rather trapezoidal plots. This was the case for the buildings Schöne Aussicht 15–18 and Hinter der Schöne Aussicht 18 , 19 , 21 and 23 . For the corner semi-detached house Schöne Aussicht 17/18 / Fahrgasse 2 / Behind the Schöne Aussicht 23, there was even a pentagonal cut.

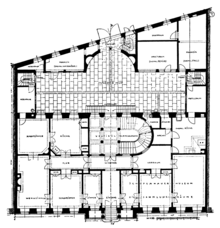

The neighboring house Schöne Aussicht 16 / Hinter der Schöne Aussicht 21, the Schopenhauerhaus , also stood on a trapezoidal plot, as the rear building was on the section of the street Hinter der Schöne Aussicht where it did not run parallel to the bank of the Main. As already mentioned in the historical part, it was actually built on one and a half plots. The property was around 30 at the Schöne Aussicht, at the lowest point, the eastern flank, around 32.40 meters wide and a total of around 830 square meters.

Exterior

Located on the beautiful views around 23 meters high, four-storey building was vertically divided into eleven axes and was of a flat, single-storey pitched roof with bilateral large Zwerchhäusern and four flanking dormers completed. The rear courtyard was in the shape of a lying, not very deep rectangle . The rear façade of the front building facing there was of an analogous design; The inner courtyard was bordered by equally high wings. The north side of the back yard was closed off by a three-part, two-story back building with a flat gable roof and a facade facing the street Hinter der Schöne Aussicht .

In terms of material, it was plastered brick buildings with wooden roofs and wooden beam ceilings , the roofs were covered with natural slate except for small parts of the dwelling houses . Stylistically, the entire complex represented a representative of high-classical architecture, which was completely free from the influences of the Empire style , which was well received elsewhere in the city around the time of construction. The only decorative elements were based on the Doric column order of antiquity .

Beautiful view

Due to the high cellar, the ground level of the ground floor at Schönen Aussicht was 1.25 meters above street level and was visually separated from it on the facade by a 0.15 meter cornice . Lockable, rectangular openings 1.30 meters wide and 0.25 meters high in the horizontal structure as the bottom element of each axis made it possible to illuminate the basement rooms.

This was followed in the horizontal structure by an undesigned plastered area about one meter high, which again separated a 0.30 meter high cornice from the next element and at the same time formed the window sills by protruding. Between the 1.30 meter wide and 2.50 meter high arched windows, the plaster was enlivened by joint cuts . At the level of the fighter between the rectangle and the arch of the window, another 0.15 meter cornice ran through the entire floor. The narrow roofing of the windows that followed the round arch and rested on the cornice gave the impression of a pilaster structure .

The design mentioned applied to the four westernmost and easternmost axes. The three central axes, on the other hand, formed a portico protruding 1.85 meters from the facade on the ground floor . Like the flanking windows, this opened in arched openings to the street. The latter were, however, significantly larger at 1.85 meters wide and 2.65 meters high. The simply profiled arches were supported in the middle by two columns with a diameter of 0.50 meters, in the corners by equally large pilasters with Doric capitals . The two lateral axes that had on the wall the same window as the rest of the ground floor, closed to the road with a simple Attica from that tops out with the window parapets was on one level.

In the central axis of the portico, a 1.35 meter high staircase with ten steps, lockable with a simple wrought iron grille, bridged the height difference to the beautiful view. Behind it was the arched, closed opening of the entrance door, 1.70 meters wide and 3.75 meters high. It was flanked by two square pillars with an edge length of 0.5 meters, which together with the columns of the porch served as supports for the three barrel vaults of the portico.

The horizontal structure was followed by a further 1.80 meters and two cornices, of which the upper one again made up the window sills, the rectangular windows of the first floor, 1.30 meters wide and 2.50 meters high. Their only decoration consisted of a slight protrusion of the walls against the facade and a simple console roofing . Except for the straight end, the windows with a set wood, fighters in the upper third and two longitudinal bars were identical to those on the ground floor.

The three central axes were also specially structured on the first floor. The portico was covered by a balcony with a simple parapet reaching up to about the level of the window sills on the floor. The middle axis, designed as a door, enabled entry from the first floor. Instead of a console roof, the window and door of the balcony were flanked by a total of four pilasters with Doric capitals. This carried a little higher than the lying Hood Mold flanking window beams with disc Fries , dentil and abschließendem Geison .

The windows on the second floor, 1.40 meters above the console canopy on the first floor and a windowsill cornice, were 2.25 meters high and 1.30 meters wide. On the floor above, they were 1.85 meters high with the same width. Profiling of the walls or roofing was completely missing, the structure of the window area corresponded to the lower floors. On the third floor, simple bars were placed in front of the third below the lowest longitudinal rung.

The third floor also had a balcony in the three central axes, but there only protruded 0.8 meters. It rested on six console stones, the underside of which described a slight S-curve. In each case two were combined to form a group flanking the central axis, one further each closed off the balcony east and west with one axis distance. At 1.30 meters wide, it was somewhat narrower than the balcony or portico below.

In order to move the balcony on the same level as the joists on the third floor, the corbels were only about 0.40 meters above the windows on the second floor. This was 0.2 meters below the cornice that formed the window sills on the third floor. There, too, the central axis opened as a door to the balcony, and a total of four Doric pilasters flanked the windows, but they had no roof.

Across the entire width of the house, after a meter above the windows, enlivened by simple profiles, the eaves followed . After another meter of roof height, simple gable dormer windows half a meter wide and one meter high decided the horizontal structure. The vertical one ended in the middle three axes with a capital dwelling 9.15 meters wide and 5.5 meters high up to its gable end. In its design, it largely took up elements of the ground floor.

There were arched windows 1.25 meters wide and 2.50 meters high between two strong cornices. The lower cornice ran about 0.5 meters above the eaves line and formed the window sills, the upper one was at the height of the transom between the rectangle and arch of the window. The latter, as well as the corners, were again accompanied by pilasters with Doric capitals within the cornice borders. To the sides was a short cranked the entire facade, a massive stone wall to pretend to a typical for the rest of the roof Ver foliation followed.

Inner courtyard and behind the beautiful view

In contrast to the front building, the rear facade of the main house to the back yard had only nine axes. In terms of dimensions and number, the individual windows on the different floors were identical. Only the basement only had openings in the three outermost axes. However, the facade there was flat and completely undesigned.

On the ground floor of the central axis, a door 1.70 meters wide and 3.20 meters high opened to an intermediate landing. From there a two-flight staircase led into the inner courtyard. As a trick by the builder, the floor level of the inner courtyard was significantly lower than the beautiful view . The courtyard enabled level access to the basement of the front building below the landing between the stairs.

Side wings adjoining the rear building, each with two window axes of 1.25 meters wide and 1.80 meters high, formed the boundaries of the courtyard. They led to a two-story courtyard building with a gable roof , which closed off the plot of land from the street Hinter der Schöne Aussicht . Because of the unusual shape of the parcel, the courtyard side of this building was designed parallel to the front building, but the street facade parallel to the street, so that when viewed from above , the shape of a compressed trapezoid emerged .

Since the entrance of the front building was already on the beautiful view over the rear exit in a line of sight with that courtyard building, the builder had used another trick here. A wide semicircular apse with the courtyard entrance was cut in the middle of the backyard building . Two niches flanking the entrance in the courtyard with barred arched ends further improved the appearance. The noble impression was reinforced by a pillar walkway above an attic cornice in the upper area of the attic.

The parts of the courtyard building on the sides of the apse were designed to be extremely functional. The largest rooms on the ground floor each had two openings, which were coupled via a central column, almost four meters high and closed with arches . To the east and west, almost in the corners of the courtyard, there were small doors to the adjoining rooms.

Above the apex of each arch, after a further 1.75 meters, the upper floor of the courtyard building was illuminated through a small, almost square window. It was repeated at the same height above the small doors. At the level of the pillar walkway, horizontally exactly between the two square windows above the apex, there was a semicircular window serving the upper and the attic storey.

The facade of the courtyard building facing the street Hinter der Schöne Aussicht was structured in a similarly functional manner. Two strips of cornice divided the facade horizontally into three equal parts. The center formed the 4.20 meter high entrance portal on the ground floor. There were four flanking windows from the lower cornice, but for the most part they only consisted of the upper round arch. Only on the east side was there a small entrance in the axis right next to the gate. From the overlying cornice, small square windows developed in the axis row. The facade was completed by semicircular windows above the middle and in the penultimate axis, which almost corresponded to those of the courtyard facade.

Interior

Only the main house can be described here, as little is known about the interior of the rear building, apart from the fact that it had a cellar like the inner courtyard.

According to the only published floor plan that allows a particularly detailed description of the ground floor, it was formerly used as a stable for the horses , a shed for the carriage, as well as a laundry room and most recently as a storage room . According to Fried Lübbecke , the former coachman's apartment on the upper floors was the last of the caretaker’s apartment , the roof was used to store hay and straw for the horses.

In the entire main house, double doors connected all rooms. Only kitchens and toilets had single-wing entrances. In the right post of all the doors there were mezuzahs installed by the former builder and mostly preserved until the end, i.e. boxes with a parchment roll with the Jewish creed . Almost all floors including the roof had ceiling heights of 5 meters, only the third floor was 3.5 meters high. The floor plan was mirror-symmetrical along an imaginary vertical central axis; often almost a symmetry developed on a fictitious horizontal central axis.

Basement and ground floor

The arched , 2.25-meter-high basement of the main building, which was supported by six low square central pillars, was reached via the inner courtyard . The main entrance at the Schöne Aussicht led to an entrance room with a rectangular floor plan, spanned by a barrel vault. This was followed by a rectangular porch , which led to an anteroom to the east and a hallway to the west. To the north, from the vestibule, one entered the atrium supported by four Corinthian columns with the staircase or the two-flight staircase behind it down to the inner courtyard.

To the west and east of the entrance room were similar vestibules three meters wide and six meters deep, each with a window facing the portico on the street. The one in the east wing was Schopenhauer's former library. It was joined by flanking, six meters wide by six meters deep, finally as, in the case of the philosopher , living room, on the other side as a bedroom, each with two window axes and doors facing north to the corridor. The largest rooms on the first floor were six meters wide and eight meters deep. Schopenhauer used the one on the east side as a bedroom, the one on the west side last served as a living room. They too each had two windows and were so deep because they included the space occupied by the hallway in the other rooms.

They opened to the corridor through doors in the north-west and north-east corner, as well as to back rooms to the north, which were almost the size of the bedrooms on the street side. On the east side it was the former kitchen of Schopenhauer, on the west side a room last used as a bedroom. They each had a window facing the courtyard; Interrupted by a small adjoining room, the side wings with their own stairwells also connected to the north. On the east side, a small adjoining room, probably hardly more than three meters wide and three meters deep, served as the apartment of Schopenhauer's housekeeper .

The only asymmetry in the floor plan was found only in the rooms that flanked the back rooms to the east and west, as the stair spindle on the east side took up around a third of the floor plan, which was not the case on the west side. On the first-mentioned side, the architect managed to divide it into three small rooms, each with a courtyard window and by enlarging the adjoining hallway to the aforementioned anteroom. The former could only be reached via the kitchen and ultimately served as an archive, chamber and meter room. On the west side, on the other hand, another kitchen could be accommodated in a large room with two windows facing the courtyard, which opened up to the south.

The atrium of the staircase was followed by a two-meter-wide flight of stairs made of oak with a step height of only 0.15 meters. From there, the stairs swung up in semicircles around a shaft, which was always illuminated by two window axes in the rear wall, to the platforms on the floors, each of which could be entered through a wide double door. On the first floor there was a chamber with a toilet under the stairs behind a blind door.

Upper floors

The influence of the baroque architecture, especially of the French hotel of the time, can also be clearly seen in the floor plan of the upper floors . Towards the Main , as in the enfilade of castle complexes, there were five living rooms each connected by wing doors, with the doors being close to the outer wall so as not to cut the rooms up.

The middle one, the salon , with three windows each, on the first and third floors with a balcony, was the largest at nine by six meters. The flanking rooms were six by six, the corner rooms eight by six meters. Behind these five front rooms was a two-meter-wide, 20-meter-long corridor that was glazed towards the stairwell. To the north in the short side wings connected to the corridor, earlier bathrooms and girls' rooms with their own stairs.

From the top floor, which housed sculptors' studios for decades, nothing has survived, apart from the very good exposure through the large dwelling houses on both sides.

Archives and literature

Archival material

Historical Museum Frankfurt

Institute for City History

- Existing account before 1816, signature 752.

literature

Major works

- Lucia Franz-Schneider: Memories of the Schopenhauerhaus Schöne Aussicht No. 16 in Frankfurt am Main. Written down by Lucia Franz-Schneider in 1911. With an afterword by Fried Lübbecke. 2nd Edition. Waldemar Kramer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1987, ISBN 3-7829-0347-1 .

- Georg Hartmann , Fried Lübbecke : Old Frankfurt. A legacy. Verlag Sauer and Auvermann KG, Glashütten / Taunus 1971, pp. 226, 227 u. 321-330.

- Wolfgang Klötzer (Hrsg.): Frankfurter Biographie . Personal history lexicon . Second volume. M – Z (= publications of the Frankfurt Historical Commission . Volume XIX , no. 2 ). Waldemar Kramer, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-7829-0459-1 . , Pp. 329-334.

- Günther Vogt: Frankfurt town houses of the nineteenth century. A cityscape of classicism. New edition. Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 3-7973-0189-8 , pp. 17-29, 52-60, 123-129 u. 275.

Further works used

- Address book for Frankfurt am Main and the surrounding area 1916. Using official sources. With the addition: Large plan of Frankfurt a. M. and surroundings. Verlag August-Scherl Deutsche Adreßbuch-Gesellschaft mb H., Frankfurt am Main 1916.

- Bernd Baehring: Stock market times. Frankfurt in four centuries between Antwerp, Vienna, New York and Berlin. Self-published by the Frankfurt Stock Exchange, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-925483-00-4 .

- Wolfgang Bangert : Building Policy and Urban Design in Frankfurt am Main. A contribution to the development history of German urban planning over the past 100 years. Konrad Triltsch Publishing House, Würzburg 1937.

- Johann Georg Battonn : Local description of the city of Frankfurt am Main - Volume I. Association for history and antiquity to Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main 1861 ( online ).

- Johann Georg Battonn: Local description of the city of Frankfurt am Main - Volume II. Association for history and antiquity in Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main 1863.

- Johann Conradin Beyerbach: Collection of the ordinances of the imperial city of Frankfurt. Fifth part. Regulations which have communication in trade and change as their ultimate purpose. Herrmannische Buchhandlung, Frankfurt am Mayn 1798.

- Johann Friedrich Boehmer, Friedrich Lau: Document book of the imperial city Frankfurt. Second volume 1314-1340. J. Baer & Co, Frankfurt am Main 1905.

- Gerhard Bott: The pleasant location of the city of Frankfurt am Main. Waldemar Kramer publishing house, Frankfurt am Main 1954.

- Alexander Dietz : Frankfurter Handelsgeschichte - Volume IV, 2. Herman Minjon Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1925.

- Alexander Dietz: Register of the Frankfurt Jews. Historical information about the Frankfurt Jewish families from 1349–1849, together with a plan of the Judengasse. Published by J. St. Goar, Frankfurt am Main 1907.

- Friedrich Siegmund Feyerlein: Views, supplements and corrections to A. Kirchner's history of the city of Frankfurt am Mayn. Frankfurt and Leipzig 1810 ( online ).

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Goethe's works. Complete edition last hand. Volume eight and forty. JG Cotta'sche Buchhandlung, Stuttgart and Tübingen 1833 ( online ).

- Evelyn Hils: Johann Friedrich Christian Hess. City architect of classicism in Frankfurt am Main from 1816–1845. Waldemar Kramer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-7829-0364-1 ( Studies on Frankfurt History 24).

- Heinrich Sebastian Hüsgen: HS Hüsgen's loyal guide to Frankfurt am Main and its areas for locals and foreigners, along with an exact map of the city and an accurate map of its areas. Behrenssche Buchhandlung, Frankfurt am Main 1802 ( online ).

- Anton Kirchner : Views of Frankfurt am Main, the surrounding area and the neighboring medicinal springs. First part. Publishing house of the Wilmans brothers, Frankfurt am Main 1818.

- Heinz Ulrich Krauß: Frankfurt am Main: data, highlights, construction work. Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1997, ISBN 3-7973-0626-1 .

- Georg Ludwig Kriegk : German bourgeoisie in the Middle Ages. New episode. Rütten and Löning, Frankfurt am Main 1871.

- Georg Ludwig Kriegk: Frankfurt civil dispute and conditions in the Middle Ages. A contribution to the history of the German bourgeoisie based on documentary research. JD Sauerländer's Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1862 ( online ).

- Friedrich Krug: The house numbers in Frankfurt am Main, compiled in a comparative overview of the new with the old, and vice versa. Georg Friedrich Krug's publishing house bookshop, Frankfurt am Main 1850.

- Fried Lübbecke: The face of the city. Based on Frankfurt plans by Faber, Merian and Delkeskamp 1552–1864. Waldemar Kramer publishing house, Frankfurt am Main 1952.

- Fried Lübbecke: The Shell Hall. Waldemar Kramer publishing house, Frankfurt am Main 1960.

- Fried Lübbecke: late harvest from the old town father Fried Lübbecke. Association of active friends of the old town in Frankfurt am Main EV, Frankfurt am Main 1964.

- Christoph Mohr: Urban development and housing policy in Frankfurt am Main in the 19th century. Habelt, Bonn 1992, ISBN 3-7749-2549-6 ( contributions to monument protection in Frankfurt am Main 6).

- Karl Nahrgang : The Frankfurt old town. A historical-geographical study. Waldemar Kramer publishing house, Frankfurt am Main 1949.

- Heinrich von Nathusius-Neinstedt: Baldemars von Peterweil description of Frankfurt. In: Association for history and antiquity to Frankfurt am Main (Ed.): Archive for Frankfurt's history and art. Third episode, fifth volume, K. Th. Völcker's Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1896.

- Tobias Picard: Living, living and working on the river. The banks of the Main in the 19th and 20th centuries in pictures and photographs. In: Dieter Rebentisch and Evelyn Hils-Brockhoff on behalf of the Gesellschaft für Frankfurter Geschichte e. V. in connection with the Institute for City History (Ed.): Archive for Frankfurt's History and Art. Volume 70, Verlag Waldemar Kramer, Frankfurt am Main 2004.

- Ludwig Schemann: Schopenhauer letters. Collection of mostly unprinted or difficult to access letters from, to and about Schopenhauer. With notes and biographical analysts. Along with two portraits of Schopenhauer von Ruhl and Lenbach. Brockhaus, Leipzig 1893.

- Hermann Karl Zimmermann: The work of art of a city. Frankfurt am Main as an example. Waldemar Kramer publishing house, Frankfurt am Main 1963.

Images (as far as bibliographically verifiable)

- Peter Becker: Pictures from old Frankfurt. Prestel, Frankfurt am Main around 1880.

- Bibliographisches Institut (Ed.): Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon. A reference book of general knowledge. Sixth, completely revised and enlarged edition. Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig and Vienna 1902-10.

- Jakob Fürchtegott Dielmann: Frankfurt am Main. Album of the most interesting and beautiful views of old and new times. 2nd Edition. Published by Carl Jügel, Frankfurt am Main 1848.

- Carl Friedrich Fay, Carl Friedrich Mylius, Franz Rittweger, Fritz Rupp : Pictures from the old Frankfurt am Main. According to nature. Published by Carl Friedrich Fay, Frankfurt am Main 1896–1911.

- Johann Hochester, Jakob Samuel Walwert: Plan of the Roemisch kayserlichen freyen Reichs choice and trade city Franckfurth am Mayn and area. Jaegerische Buchhandlung, Frankfurt am Main 1792.

- Max Junghändel: Frankfurt am Main. Photography from nature by Max Junghändel. In collotype done by the publishing house for art and science formerly Friedrich Bruckmann in Munich. Published by Heinrich Keller, Frankfurt am Main 1898.

- Wolfgang Klötzer (Ed.): Frankfurt Archive. Archiv-Verlag Braunschweig, Braunschweig 1982–88.

- Adolf Koch: From Frankfurt's past. Architectural studies drawn and described from nature. Published by Heinrich Keller, Frankfurt am Main 1894.

- Eberhard Mayer-Wegelin: Early photography in Frankfurt am Main: 1839-1870. Schirmer / Mosel Verlag GmbH, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-921375-87-8 .

- Matthäus Merian the Elder & Heirs: Francofurti ad moenum, urbis imperialis, electioni rom.regum atque imperatorum consecratae, emporiique tam germaniae. Quam totius europae celeberrimi, accuratio declinatio. Jäger'sche Buchhandlung, Frankfurt am Main around 1770.

- Johann Friedrich Morgenstern: Small views of Frankfurt am Main in 36 engraved and illuminated souvenir sheets. Facsimile of the edition by Friedrich Wilmans, Frankfurt am Main 1825 in color collotype. F. Lehmann am Römerberg 3, Frankfurt am Main 1913.

- Friedrich August Ravenstein: August Ravenstein's geometric plan of Frankfurt am Main. Publishing house of the geographical institute in Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main 1862.

- Christian Friedrich Ulrich: Geometric floor plan of Frankfurt am Mayn. Published by Carl Christian Jügel, Frankfurt am Main 1811.

- Christian Friedrich Ulrich: Geometric ground plan of the Freyen city of Frankfurt and Sachsenhausen with their fertile surroundings up to a quarter of an hour away in 1819. Publishing house by Carl Christian Jügel, Frankfurt am Main 1819.

Web links

References and comments

Individual evidence

- ↑ Boehmer, Lau 1905, pp. 224–226, Certificate No. 293; the oldest document mentioned in the literature in which the name is mentioned in Middle High German. This also coincides with the statements in Battonn 1861, pp. 196-198, which provide no earlier evidence and only the Latin name campus piscatorum .

- ↑ a b c Hartmann, Lübbecke 1971, p. 321.

- ↑ Battonn 1861, p. 188; Reference to a (undated) fee regulation handed down by the Frankfurt chronicler Achilles Augustus von Lersner, which differentiates between old town, new town, Sachsenhausen and Fischerfeld in terms of amount.

- ↑ Battonn 1864, p. 196 and 197; According to the vicariate books of the Bartholomäusstift from the 14th and 15th centuries, in which church interest payments from fish ponds in the area were entered.

- ↑ Battonn 1864, p. 197; according to a mention by Baldemar von Petterweil around the middle of the 14th century and a council decree from 1457 in favor of the riflemen working on the site, whereby the white tanners are mentioned in a subordinate clause.

- ↑ Battonn 1864, p. 189; Quote: "It was by his account [that of Baldemar of Petterweil] only one row houses that were divided by three notches or narrow streets from noon to midnight." .

- ↑ Kriegk 1862, p. 255 and 256; Population numbers according to the Bedebuch , no longer mentioned in the Bedebuch of the 15th century, the last mention in the Bedebuch in 1397 already reveals no more houses, but gardens and fields.

- ↑ Franz-Schneider 1987, p. 51; to Lübbecke.

- ↑ Battonn 1864, p. 190; Quote: "But it can be assumed that it [the suburb] was torn down at the same time as new trenches were dug around the city for fear of the Hussites, and where the arithmetic trench probably took its place, [...]" .

- ↑ Bott 1954, p. 58.

- ↑ Kriegk 1862, p. 256.

- ↑ Battonn 1864, p. 200 and 201; the term Krautschützen served to distinguish it from the society of bow and crossbowmen, Kraut and Loth was a contemporary term for powder and lead in this context . According to the tradition of the Frankfurt chronicler Achilles Augustus von Lersner , the Schützenhaus was first built out of wood in 1472 with a grant from the council and probably replaced by a stone building in 1679, which, according to Battonn's eyewitness report, existed until 1805.

- ↑ Goethe 1833, pp. 19-22.

- ↑ Kriegk 1871, 290 ff .; Kriegk's depiction of prostitution in Frankfurt am Main from the late Middle Ages to the early modern period has lost none of its validity due to the lack of modern depictions.

- ↑ Battonn 1861, p. 189; Quotation: "[...] the common women [an old term for prostitutes] who came here during Mass times and stayed in the wine houses in Fischerfelde [...]" , according to the tradition of the Frankfurt chronicler Achilles Augustus von Lersner.

- ↑ Bott 1954, p. 36.

- ↑ Battonn 1863, pp. 49, 50, 54, 56, 58, 59 and 108-110; numerous demolitions and new buildings between Predigerstrasse and Alter Brücke in the 1790s and 1800s were mentioned.

- ↑ Lübbecke 1952, p. 128.

- ↑ Feyerlein 1809, p. 150 and 151; According to Feyerlein's description, the quay of the beautiful view and the houses there were only completed up to the corner of Mainstrasse in 1808, behind which the area fell straight down to the old level. The year 1820 results from the assumption of a building line that directly followed the embankment.

- ↑ Vogt 1989, pp. 123, 124, 274 and 275; The statement made here at least for the entire course without individual evidence, which is based more on the dating sequence of individual houses, is underpinned by the comparison of Ulrich 1811 and Ulrich 1819, according to which only two new houses were built at the Schöne Aussicht in almost ten years.

- ↑ Hils 1988, p. 76 and 77; From the minutes of the Legislative Assembly of March 29, 1825, printed here in extracts, it emerges that the paving of the Schöne Aussicht was only missing in front of the grounds of the Old City Library.

- ↑ The establishment of the Judengasse. In: judengasse.de. Retrieved September 1, 2010 .

- ^ The fire of 1711. In: judengasse.de. Retrieved September 1, 2010 .

- ^ The fire of 1721. In: judengasse.de. Retrieved September 1, 2010 .

- ^ Judengasse / Wall / Gates. In: judengasse.de. Retrieved September 1, 2010 .

- ↑ a b Dietz 1907, p. 321.

- ↑ Dietz 1925, p. 711.

- ↑ Dietz 1925, p. 717.

- ↑ Stone house. In: judengasse.de. Retrieved September 1, 2010 .

- ↑ Dietz 1907, p. 321, and Dietz 1925, p. 718, give 1809 as the year of death, in Franz-Schneider 1987, p. 37 u. 47, is given in 1803. Since Lübbecke provides information in the following that is not mentioned by Dietz and owes its data to the "notification from the Frankfurt registry office [...]", preference should be given to this information.

- ↑ Dietz 1907, p. 322.

- ↑ Dietz 1907, p. 322 shows only 14 children (six of them in detail), here too the much more extensive information from Lübbecke in Franz-Schneider 1987, p. 37 and 49, to be preferred.

- ↑ a b The street fire of 1796. In: judengasse.de. Retrieved September 1, 2010 .

- ↑ Red Tower. In: judengasse.de. Retrieved September 1, 2010 .

- ↑ Vogt 1989, p. 126 and 127.

- ↑ Vogt 1989, p. 17 and 18; In particular, the comparison to the third city expansion in Darmstadt (planning from 1790, execution from 1791) is used, which provided for a Magistrale according to baroque ideas, to which the other streets had to be subordinate.

- ↑ Zimmermann 1963, p. 103 and 104; In addition to information on the parcel dimensions, it is pointed out that the road widths in the execution then fluctuated between a maximum of 16 meters (Fischerfeldstrasse and Rechneigrabenstrasse) and a minimum of 9 meters (Wollgraben), which, however, was chosen deliberately to liven up the street scene.

- ↑ Beyerbach 1798, p. 1102; Quote: "But II. In the district of the Brückhof and in the kennel no construction sites for fire - or rioting craftsmen can be given, [...]" . A supplement with regard to the signs can be found in the concept of the conditions of sale from 1806 in the Institute for City History Frankfurt am Main, inventory of the invoice before 1816, signature 752.

- ↑ Hils 1988, p. 28.

- ↑ a b Franz-Schneider 1987, p. 52; to Lübbecke.

- ↑ Vogt 1989, p. 54 and 55; the example of the corrections made by Hess to the plans for the Paulskirche, which his predecessor Johann Andreas Liebhardt had worked out. He changed the height of the tower from 80 Schuh to 116 Schuh, since according to Vitruvius the height should be taken as half of the addition of the width. He went on to explain that even after Andrea Palladio's calculation, who used the square root of the product of length and width, the same result was obtained.

- ↑ Mohr 1992, pp. 12, 13, 117 and 134; the references to Hess because of multiple violations of the regulations are unequivocally proven by excerpts from numerous Senate minutes from the early 19th century. With reference to the sources, without naming them in detail, Mohr also doubts Hess's authorship of the individual building plans, and at least after 1802 ascribes them mainly to Bunsen; Hess was therefore primarily responsible for the development plan.

- ↑ Vogt 1989, p. 129; without individual evidence and also the only known mention of the amount in the literature, therefore probably based on archival documents or excerpts that are no longer available.

- ↑ Baehring 1985, pp. 70-75.

- ↑ Franz-Schneider 1987, pp. 27, 29 and 48; based on the memoirs of Franz-Schneider. Lübbecke added that in the Frankfurt address book of 1844 there was actually evidence of a trader Wolf Zacharias Wertheimber in the house mentioned in Judengasse.

- ↑ Franz-Schneider 1987, pp. 25, 37 and 49; according to the memoirs of Franz-Schneider as well as the information given by Lübbecke after "Communication from the Frankfurt registry office [...]". Regarding Sara, who is only mentioned by Franz-Schneider as a divorced "Baroness Hirsch" , the family tree in Dietz 1907, p. 322 shows that she married the banker Joel Jakob von Hirsch in Würzburg and probably his name wore.

- ↑ Franz-Schneider 1987, p. 25 u. 37; Here the memoirs of Franz-Schneider and the statements of Lübbecke contradict each other, whereby the former is given preference. Franz-Schneider remembers that “we moved to the Schöne Aussicht in 1856” , Lübbecke mentions May 11, 1852 as the date of birth, but then mentions that when she moved into the house she would be “seven years old, just as old as in her description “ .

- ↑ Klötzer 1996, p. 329; Klötzer should be added here with regard to the address of Schopenhauer's first apartment, which is determined there at Alte Schlesingergasse 32. Until 1847, the district order from the Seven Years' War still existed in Frankfurt am Main, but after the conversion the Alte Schlesingergasse only had 20 house numbers. In the source used by Klötzer, according to Krug 1850, p. 67, 31 can only mean the designation E32 (common in 1831), which after 1847 corresponded to house numbers 16/18.

- ↑ Schemann 1893, p. 406; Schopenhauer wrote this description down after moving to the neighboring house, literal quote: “You know, I now live in Wertheimber's house no. 16, ground floor, right, glass door, ring hard. ".

- ↑ Klötzer 1996, p. 330 u. 332.

- ↑ a b Franz-Schneider 1987, p. 55; to Lübbecke.

- ↑ Klötzer 1996, p. 332.

- ↑ Franz-Schneider 1987, p. 12 u. 13; based on the memoirs of Franz-Schneider.

- ↑ Klötzer 1996, p. 330.

- ↑ Franz-Schneider 1987, p. 12; based on the memoirs of Franz-Schneider.

- ↑ Franz-Schneider 1987, pp. 14, 16 and 17; based on the memoirs of Franz-Schneider.

- ↑ Franz-Schneider 1987, p. 12 u. 14; based on the memoirs of Franz-Schneider.

- ↑ Franz-Schneider 1987, p. 17 and 19; based on the memoirs of Franz-Schneider.

- ↑ Franz-Schneider 1987, p. 14 and 15; based on the memoirs of Franz-Schneider.

- ↑ Franz-Schneider 1987, p. 18 u. 19; based on the memoirs of Franz-Schneider.

- ↑ Klötzer 1996, p. 333.