shrapnel

A shrapnel , also called a grenade rake , is an artillery shell that is filled with metal balls. Shortly before the target, these are ejected forward by a propellant charge and thrown towards the target.

The predecessor of shrapnel was the grapple , in which small bullets or other metal parts were only packaged in a thin shell without an additional explosive charge, so that they fanned out wide at the cannon muzzle. The effective range was therefore limited to approx. 600 m.

Fragments that are created when ordinary grenades or aerial bombs explode are sometimes incorrectly referred to as shrapnel .

overview

Muzzle loading ammunition

The German piece masters of the 16th century were already familiar with the garnet handle in a less perfect form .

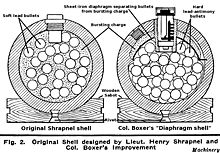

It is also known from the siege of Gibraltar (1779–1783) that a Captain Mercier temporarily used such ammunition. Nevertheless, the British officer Henry Shrapnel (1761–1842) is considered to be the inventor of this ammunition, as he consistently developed the previous solutions in 1784. The ammunition should not replace the grapple, but rather have the same effect at longer distances. The shrapnel was originally a thin hollow ball filled with explosives in which musket balls were embedded. The amount of explosives was rather small; it was enough to burst the hollow ball, but not to widely scatter the musket balls. The little bullets moved more or less in the direction in which they were fired by the gun. This was a new principle and made ammunition so deadly. Officially, the proposal did not reach the Artillery Committee until 1792 and was recommended for use in the British Army in 1803 after a demonstration by Major Shrapnel. The first operation took place in April 1804 during the fight against the Dutch around Fort Nieuw-Amsterdam . The British government decided in 1852 to name the ammunition after its inventor Henry Shrapnel.

The construction of Shrapnel was not entirely convincing. About a fifth of the ammunition used ignited prematurely. Various attempts have been made to counter the problem. The British officer Edward Mounier Boxer succeeded in doing this in 1852 by separating the explosive charge and bullets. It turned out that when the metal balls were fired, friction and thus heat could develop, which ignited the surrounding explosive charge. The shrapnel, improved by Boxer, was approved by the British Army on a trial basis in 1854 and, after minor changes, was finally adopted in 1864.

Breech-loading ammunition

A few years after the establishment of the shrapnel, the gun technology changed fundamentally. The hitherto prevailing smooth muzzle loaders were drawn Hinterlader replaced. Accordingly, the shrapnel was given the shape of a long bullet .

Shrapnel are hollow iron projectiles filled with lead balls weighing 13 to 17 g. In order not to change their position when the bullet rotates during flight, these are fixed by pouring sulfur or rosin . In this way, disturbances in the regularity of the flight path are to be avoided. There were also mixed charge shrapnel grenades in which the bullets were embedded in the explosive ( unitary bullet ). With these standard projectiles, however, the explosives were not detonated in the shrapnel position and only burned.

A central cavity in the head or bottom of the grenade contains the explosive charge ( chamber charge ) or ejection charge of black powder , which is ignited in the air by the detonator (time or powder flame detonator) before reaching the target. If the powder charge is on the floor of the projectile, it is called a floor chamber shrapnel. As with a short-barreled shotgun, the bullets are ejected forward from the body of the projectile, but the rotation of the projectile disperses them. This scatter cone hits the ground in an elongated ellipse. The charge with black powder creates a noticeable white cloud of smoke in the air, which makes it easier to observe the detonation point and to correct the individual shots. The empty shrapnel shells that hit after the spherical clouds are also called hollow blowers . Since shrapnel must detonate before they reach the surface of the earth, not impact detonators but time detonators are used.

The distance of the detonation point from the target is about 50 m in order to allow the bullets to spread as widely as possible. The distance of the shrapnel from the ground at this point in time is between 3 and 10 m, depending on the range and type of fire.

They were used against soft targets , i.e. against mounted and unmounted troops and unarmored vehicles. The effect against upright, uncovered targets was devastating if the location of the detonation point in relation to the target could be precisely observed, at that time up to about 5000 meters. During the First World War , the shrapnel was gradually replaced by the high-explosive grenade , after the transition to trench warfare meant that unsecured targets could hardly be grasped. In the final phase of the First World War this would have been possible again, but there were hardly any artillerymen who mastered the complex procedure.

The principle of shrapnel is currently being used again in the form of AHEAD ammunition against soft targets and as a distance-active protective measure for close defense against missiles such as missiles.

literature

- Alfred Geibig: Explosive and scattering devices, cutting and debris projectiles . In: The power of fire - serious fireworks of the 15th – 17th centuries Century in the mirror of its neuter tradition . Art collections of the Veste Coburg, Coburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-87472-089-2 , p. 177–226 (On early projectiles of the 15th – 17th centuries).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ludwig Darmstaedter : Handbook on the history of natural sciences and technology , Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg , 1908, p. 285 [1]

- ↑ a b c Oliver FG Hogg: Artillery: its Origin, Heyday and Decline , Archon Books, 1970, SBN 208 01040 8, pp. 179-182