Frankfurt city fortifications

The Frankfurt city fortifications were a system of defenses for the city of Frankfurt am Main that existed from the Middle Ages until the 19th century. Around the year 1000 a first city wall was built , which essentially enclosed the area of the Königspfalz Frankfurt . In the 12th century the settlement expanded to the area of today's old town . The so-called Staufen wall was built to protect it . From 1333 the new town was built north of the old town , which was surrounded by an additional wall ring with five city gates. The Frankfurter Landwehr , established in the 15th century, extended around the entire territory of the Free Imperial City . From 1628 the medieval city wall was expanded into a star hill fortress under city architect Johann Wilhelm Dilich .

Frankfurt has consistently stayed out of military conflicts since its defeat in the Kronberg feud in 1389 and relied on a network of diplomatic relations inside and outside the empire. As a result, the city fortifications - as far as has been handed down - had to prove themselves in a siege only once in the almost eight centuries of their existence, namely in July 1552 during the prince uprising .

From the 18th century, the fortifications were militarily useless and stood in the way of the city's development. Not least because they were 1806 to 1818 razed . Today, with the ramparts, they form a green belt around the city center. Seven towers are still preserved, including the Eschenheimer Tower , an approximately 200-meter-long piece of the Staufen wall, remains of the Landwehr and a 90-meter-long piece of a casemate of the baroque Sternschanze fortress that was only uncovered in 2009 .

The first city wall

Königspfalz Frankfurt

Frankfurt's oldest fortifications were built to protect the Carolingian Palatinate, first mentioned in 822 . For a long time their location was not exactly known. Until the 1930s it was considered the predecessor of today's Saalhof . Heinrich Bingemer was able to prove through excavations in 1936 that the Saalhof only came from the Staufer period , and therefore assumed that the Carolingian Palatinate was further to the east. In fact, in 1953, during archaeological excavations in the inner core of the old town, which were made possible after the destruction of the old town by the air raids on Frankfurt am Main in World War II , the remains of the Palatinate were found west of the cathedral in the basement of the former Golden Scales .

The Palatinate was located on the Cathedral Hill , a flood-protected hill in the east of the old town. Originally, it was an island between the Main, which ran south, and the Braubach , to the north, a tributary that silted up in the first Christian millennium and channeled into the Middle Ages . South of the cathedral hill was the ford to which Frankfurt not only owes its name, but also its existence. Between the cathedral hill and the Carmelite hill to the west of it, a swampy depression stretched across today's Römerberg down to the Main.

Until the early 20th century it was undisputed that Carolingian Frankfurt included not only the Cathedral Hill, but also the Carmelite Hill, i.e. the southwestern quarter of today's old town . This assumption was based on the thesis already mentioned that the Palatinate was a predecessor of the Saalhof and would have been located exactly in the middle of the first fortification. Accordingly, it also shows a plan by the geographer Christian Friedrich Ulrich from the first decade of the 19th century, in which the allegedly oldest city limits and at the same time the presumed course of the oldest city wall was entered.

The wall would have run from the bank a little above today's Old Bridge to the north along the Wollgraben to the later Dominican monastery . From there it would have followed the course of today's Braubachstrasse and Bethmannstrasse to the west and, shortly before the western end of today's Weißfrauenstrasse, would have turned back south to the Main , where it would have connected again along the bank to the eastern starting point.

Findings of archeology

History of the excavations

When the supposed remains of the wall came to light during the construction of the Dompfarrhaus on the northern Domplatz, and later in the cellars of several houses in the western old town area, the idea of early medieval fortification given by Ulrich was still confirmed. However, it was only when Braubachstrasse broke through the old town from 1904 to 1906 that extensive scientific excavations could be carried out as planned. The architect Christian Ludwig Thomas , commissioned by the Historical Museum , was able to prove the north and north-west of the wall in over 50 excavation shafts along the new street.

It was not until after the Second World War, between 1953 and 1955, that archaeologists again dealt with the city wall in the area of the former main customs office (today Haus am Dom ). Evidence of parts of the southern (i.e. along the Main) and a small piece of the western course under the Saalgasse could be provided in the course of Otto Stamm's investigations in the area of the Saalhof between 1958 and 1961. The last excavation to date on the wall took place again in 1976 on the property of the cathedral parish house. Investigations to prove the southeastern and eastern course have not yet been carried out. Also, the stratigraphy , which was probably severely disturbed by the construction activity of the Middle Ages in the area of the Römerberg and finally destroyed by the construction of the underground car park in the 1970s, only allowed very few conclusions to be drawn about the course at this point.

Findings and current state of research

The clearest picture is drawn from the findings on the appearance and composition of the wall. On average, it was about two meters thick and high, on the southern side facing the Main the thickness - probably for purely psychological reasons - was even three meters, which is why it is often listed here as a "three-meter wall" in the findings catalogs. The defense work consisted of rubble, roughly hewn quarry stones , but also partly better-made work pieces made of basalt and Vilbel sandstone , which probably came from the demolition of Roman buildings. The material was quite clumsy and only layered on top of one another according to plan in a herringbone-like composite on the front sides , the mortar of extremely poor quality, basically only clay mixed with plant fibers and animal hair . According to Thomas, the foundations were so inadequate that the wall tilted up to 30 centimeters from the plumb line when it was not covered by civilization rubble. In places he also uncovered later repairs with better mortar, which documents the importance of the wall, apparently they wanted to preserve it despite its serious structural defects.

With regard to the dating, the findings alone give a less clear picture. Thomas dated the wall to the 9th century due to the remains of civilization found in the immediate vicinity, but above all so-called Pingsdorf ceramics , which were considered Carolingian at that time, and attributed the building owner status to Ludwig the German . During the excavation in 1976, a beaker tile made of coarse mica was found in a pit under the wall. Beaker tiles appear towards the end of the 10th century, and the already mentioned Pingsdorf ceramics tend to be set in the period from 900, so that at least the archaeological findings made so far speak more for a city wall from the late Ottonian than the Carolingian era. In addition, however, there is also a document from the year 994, which describes the city for the first time as "castello" , i.e. a castle, which suggests the existence of a city wall at that time and which corresponds perfectly with the results of the archaeological investigations.

The course of the wall is best documented in the northwest due to the numerous excavations at the turn of the century and the still luxurious situation for archaeological conditions at that time of being able to dig in completely undisturbed cultural layers. The defense system stretched in an almost straight line from the Hainer Hof north of Kannengießergasse to a 1.10 meter wide gate that Thomas discovered in the Borngasse area . From here it extended straight ahead to the stone house and then, contrary to expectations, turned sharply towards Römerberg.

The findings of a wall running in an east-west direction on the northern Saturday mountain suggest the existence of another gate system, where one still leaves the Römerberg and enters the old market in the direction of the cathedral. If one draws a connection from here with the finds in the area of the Saalhof, the wall running in east-west direction must have described an almost right-angled turn and looked as a straight line to connect to the thicker wall on the banks of the Main. The strong disturbance of the soil under the Römerberg, noted by Thomas, makes it just as possible that the east-west section mentioned belonged to a later period, and the wall directly in a quarter circle connection from its north-westerly course, the south-westerly section of which is under Otto Stamm found the Saalgasse, looked for the southern piece. The latter has only been proven archaeologically up to the level of the ghost gate . Their simultaneity with the Ottonian city wall is also controversial.

Presumably, the "three-meter wall" also followed the natural course of the river east of the little ghost gate, the bank of which at that time was roughly level with the southern Saalgasse, and ran east of the cathedral, roughly at the middle of the Kannengießergasse, again at a reduced width in north-south Direction to join the occupied route on today's Braubachstraße.

The archaeological findings, which were still surprising at the beginning of the 20th century, were only able to explain the excavations carried out in the post-war period. The Palatinate with the associated farm buildings and the predecessor building of the cathedral, the Salvator Church, consecrated in 852, was located exactly in the middle of the area enclosed by the wall. The Carolingian Frankfurt was therefore significantly smaller than had previously been assumed and, according to today's knowledge, was only fortified by the following Ottonian dynasty around the year 1000.

The Staufen Wall

At the beginning of the 11th century, the Carolingian royal palace had already become dilapidated. Probably between 1018 and 1045 it fell victim to a fire, the area was quickly built over. It was not until 1138 that Konrad III was elected king . had a royal castle built on the Main with the Saalhof. The settlement around the castle gradually developed into a small town after the middle of the 12th century. With the later so-called First City Expansion , the settlement boundaries reached beyond the northern Main Arm, which had meanwhile silted up or filled up. At the end of the 12th or beginning of the 13th century, the enlarged settlement was surrounded by a new city wall, the Staufen wall . It enclosed an area of about 0.5 square kilometers, today's Frankfurt old town.

The new city wall started on the banks of the Main just above the bridge, stretched north along the Wollgraben to the later Dominican monastery and from there in a wide arc northwest to the Bornheimer Pforte on the Fahrgasse . From here it ran in a westerly direction along today's Holzgraben to the Katharinenpforte , from there in an arch over the Kleiner and Großer Hirschgraben to the southwest and shortly before the western end of today's Weißfrauenstrasse bend south to the Main. The Main Wall ran along the bank .

The expansion coincided roughly with the introduction of the crossbow in the wake of the Crusades , which is why the fortification grew in height. A battlements ran along the roughly seven-meter-high and two to three-meter-thick wall of rubble stones , with a dry trench facing the outside. The city wall had three main gates, from west to east the Guldenpforte , at the western end of the Weissadlergasse ; the Bockenheimer Pforte (later called Katharinenpforte ) between Holz- and Hirschgraben; and the Bornheimer Pforte at the northernmost point of the tramline.

The appearance of the Guldenpforte was only handed down through the siege plan of 1552 as a round, unadorned tower with a conical roof. The Katharinenpforte consisted of two simple buildings, the outer gate and a stronger, square inner tower with a high slate roof , roof bay window and lantern . This tower stood at the southern end of the street known today as Katharinenpforte, which got its name from the Katharinenkirche founded by Wicker Frosch in 1354 . In older depictions, the Romanesque architectural style of the gate can be recognized by the size and shape of the windows and on the ground floor by the round arched passage with its typical, unplastered arching.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Katharinenpforte was extensively renovated several times in order to be able to continue using a prison located there. Apparently the building with its extremely massive walls was particularly suitable for this purpose. From today's perspective, the most prominent prisoner is likely to have been Susanna Margaretha Brandt , the historical role model for Goethe's Gretchen . She lived here from her arrest on August 2, 1771 to her execution on January 14, 1772.

The Bornheimer Pforte was a double gate: the eastern archway was larger and intended for wagons, the western one, about half the width, for pedestrians. It had a simple square tower with a high slate roof. Like its western counterpart, it has served as a prison since 1433. In 1719 it was badly damaged in the Great Christian Fire.

Besides the aforementioned main gates there were seven smaller ports: the Mainzer Gate at the Alte Mainzer Gasse , the Fischerfeldstraße gate east of the bridge on Main, west of the bridge, the fishermen gate at the Great Fischergasse that Metzgertor south of the screen house , the Holy Spirit Gate on medium length Saalgasse, the driving gate in the late Fahrtor , the wooden gate at the southern end of Karpfengasse (north-south roughly between today's roads Fahrtor and on Leonhardstor abandoned after the Second world war) and Leonhard gate at the 1219 donated Leonhard Church . Because of their small size, the secondary gates were often belittled as little wickets in the vernacular. Their appearance has not been passed down, as they underwent major structural changes as early as the middle of the 15th century, almost a century before the first complete pictorial representations of the city.

The Staufen wall was maintained after the second city expansion in 1333. The best evidence of this were two round towers erected on the wall in the middle of the 14th century, at a time when the city was already being fortified. The Fronhofturm , named after a farm yard of the Bartholomäusstift located here, stood at the end of Predigergasse (east-west connection roughly between today's eastern Domplatz and Kurt-Schumacher-Straße, abandoned after the Second World War), the Mönchsturm, named after the neighboring Dominicans, was on the In the middle of an imaginary line between the choir of the Dominican Church and the Stone House in Judengasse . In all likelihood, the towers should serve as a defense for the endangered corner of the wall at the Fischerfeld.

It was not until the end of the 16th century that larger pieces were torn off, as can be seen on the bird's eye view plan by Matthäus Merian from 1628: in 1583 a large piece fell southwest of the Katharinenpforte, in 1589 there was a breakthrough at the northern end of the Fahrgasse and in 1590 just like that at the opening of the Hasengasse towards the Zeil . In the same year the Guldenpforte was demolished, shortly after 1765 the Bornheimer Pforte, 1790 the Katharinenpforte, 1793 the Fronhofturm and in 1795 large parts of the Mönchsturm. The latter, used as a powder tower, almost led to a catastrophe in the Great Jewish Fire in 1711, but the flames could just be prevented from spreading, and as a result the tower remained unused from then on. The Bornheimer Pforte clock, which the neighborhood had requested as early as 1603, was placed on the tower of the nearby armory at the Konstablerwache , which was demolished in 1886 . The bell was 1776 burned the same year St. John's Church in Bornheim as a makeshift.

After it was softened in the early 19th century, an approximately 600 meter long piece of the Staufen wall on the western rear side of the Judengasse up to the Fahrgasse was still connected until around 1880. Within a few years, more than 500 meters of it fell when the Battonnstrasse breached and a school building was built at the Dominican monastery. The foundations of the monk's tower were archaeologically excavated in 2011 and should now be made visible in the pavement of the street.

The late medieval city expansion

On July 17, 1333, Emperor Ludwig IV permitted the second city expansion , which tripled the previous city area. It would take another four centuries until the city's population of 9,000 at that time had grown so much that the Neustadt in front of the Staufen wall was completely built up. Nevertheless, shortly after the city expansion, the construction of a new city wall around the sparsely populated suburb began, which stretched over more than 100 years in several sections.

The work started in 1343 from two sides: in the west at the Weißfrauenkloster and at the Bockenheimer Tor , in the east at the Allerheiligentor . At first the construction proceeded slowly and, as far as can be understood from the medieval master builder and arithmetic master books, hardly according to an overall concept. Something like a program can only be pursued with the reinforcement of the main front in the 1940s and 50s of the 15th century. The introduction and rapid development of firearms apparently accelerated the work from this point onwards, so that the entire fortification line was completed at the beginning of the 16th century.

Like its predecessor, the fortification began above the old bridge, stretched to the Dominican monastery to the north, then to the east, and from here it continued to follow the line of today's installation ring . From east to west these are Lange Straße , Seilerstraße , Bleichstraße , Hochstraße and finally Neue Mainzer Straße down to Schneidwall . Nothing changed in the course of the Main Wall. For the first time, the suburb of Sachsenhausen, south of the Main, was included in the protection of the wall.

The wall was six to eight meters high and about 2.5 to three meters thick at the top of the wall. To save material, blind arches about one meter deep were laid in the inside of the wall - like the Staufen wall . A continuous battlement with a parapet about two meters high , which was interrupted by battlements and loopholes , ran along the wall . It can be reached either through narrow and steep wooden stairs, or through stone spiral stairs, so-called snails .

The parapet walkway, which was paved with slabs, was partly covered with a slated gable roof, the rest without a roof was occupied in various places with small houses that were used by defenders and guards to stay. The most famous of these buildings was the Salmensteinsche House , built around 1350 in the area of today's Rechneigrabenstrasse . It inspired the architects of the new town hall building in the 19th century, so that the smaller town hall tower Kleiner Cohn in the roof area is an exact copy of the house. However, after being damaged in World War II, it has only had a flat emergency roof to this day.

In front of and behind the wall were two kennels , each three to four meters wide , and in front of the outer kennel there was an eight to 10 meter wide wet ditch with another low wall in front of it. In addition to the Main, various smaller bodies of water fed the ditch with water. The Frankfurt fishermen's guild also managed the fishing in the ditch. The Rechneigrabenweiher in the Obermainanlage and the Bethmannweiher in the Bethmannpark are still existing remnants of the trench.

A total of 55 towers were used to strengthen the wall, 40 of them on the north side of the Main and 15 in Sachsenhausen. Most of them did not emerge until the 15th century. Most of these towers were round and protruded little beyond the wall. The battlements of the city wall either went through the towers or was led around them.

Gates

Only a few gates led through the land wall: in the west the Galgentor , in the northwest the Bockenheimer Tor , in the north the Eschenheimer Tor , in the northeast the Friedberger Tor and in the east the Allerheiligentor . On the Sachsenhausen side, however, there was only one gate, the Affentor in the south ; the Mühlpforte in the east and the Oppenheimer Pforte in the south-west were closed again before 1552, as can be seen on the siege plan.

The gate structures consisted of two somewhat stronger gate towers on both sides of the moat and a kennel in between. In order to be able to defend the gates better, in most cases they were staggered, only the Bockenheimer and the Eschenheimer Tor had straight passages. In an emergency, earth and stones could be poured into the passage through an opening in the arched gate, making the gate impassable.

Despite its chilling name, the Galgentor was the most important, as traffic to and from Mainz passed through it. The emperors also used to move into the city through the Galgentor when they were elected. Its square gate tower, built between 1381 and 1392, was therefore particularly representative: on the outside, under Gothic canopies, were the statues of Saint Bartholomew and Charlemagne next to an imperial eagle standing on a lion . In 1808 the entire complex with the tower and the bridge in front was demolished.

As one of the first completed fortifications of the new city wall, the tower of the Bockenheimer Tor was built between 1343 and 1346. Initially referred to as Rödelheimer Pforte , the later name was only transferred from the Katharinenpforte to it in the course of the 15th century. After the gate was badly damaged by lightning in 1480 and 1494, it was rebuilt in 1496 and decorated by the painter Hans Fyoll . In 1529 it was secured by a roundabout , in 1605 the old gate was closed and a new one was built next to it. The demolition took place in 1808, after the city architect at the time had already pointed out the great dilapidation in 1763.

The most important tower was the Eschenheim Tower, which was built between 1400 and 1428 and is still preserved today, behind the city gate of the same name. It was already the second tower at this point. The foundation stone for its predecessor was laid in 1346. The Vorwerk with the two-arched stone bridge was demolished in 1806. In contrast, despite several attempts to tear it down in the 19th century as an obstacle to traffic and an insult to the aesthetic feeling of the Biedermeier period , the tower repeatedly found prominent advocates, including the Grand Duke Karl Theodor von Dalberg , in whose honor the tower was named in the 19th century Karlstor wore.

According to official records, the Friedberger Tor already existed in 1346, but its tower was not built until 1380. It was rectangular and crowned with a high, hipped gable roof with a lantern. Its porch already fell victim to the improved fortification of the 17th century, the stand-alone tower, which was inhabited by a tower keeper until 1812.

In the beginning, the Allerheiligentor was named Rieder Pforte after the Riederhöfe, about half an hour's walk away . In historical documents it is sometimes mentioned as the Hanauer Tor . It was only when the All Saints Chapel was built nearby in 1366 that this name slowly passed over to the gate. The exact construction date of the representative gate tower fluctuates in historical sources between the 1340s and the 1380s; it was demolished in 1809.

The Sachsenhausen Gate has been known as the Affentor since the end of the 14th century . There are various explanations for this name, according to Johann Georg Battonn it got its name from a nearby house on the corner of the monkey . In its whole form it was much more compact than the buildings north of the Main. Above the gate was a square tower, the exact date of its construction can no longer be traced. After 1552 the gate was provided with rondelles on two sides, after 1769 the roof was given a baroque turret to accommodate the clock of the broken Sachsenhausen bridge tower. It was completely demolished in 1809.

Main bank and bridge towers

The defense of the banks of the Main was particularly important for the protection of the city. On the downstream side, the Mainz tower on the north bank and the Ulrichstein on the south bank guarded the entrance to the city. Upstream, the marshy fishing field prevented a possible attacker from direct access to the city wall, while the Sachsenhausen bank between the city wall and the Main Bridge was secured by a wall with five strong towers.

The old bridge itself was protected by two bridge towers. Its gates were closed at night so that no one could cross the bridge at night. As early as 1306, documents reported for the first time about the towers, which were destroyed by floods and ice on February 1st of the same year. Apparently it was rebuilt in a very short time. In July 1342, the less massive Sachsenhausen bridge tower fell victim to another flood, but was immediately rebuilt from 1345 to 1380.

The Frankfurt bridge tower has been known as the old bridge tower since 1342 , which is why it can be assumed that it was built between 1306 and 1342. It served as a prison, and in 1693 the torture was moved here from the Katharinenpforte. The square tower had a very steeply hipped slate roof with large dormers and an ogival passage on the ground floor. While the corners showed cuboids, the surfaces were plastered and designed to be representative at all times. The shape of the design was, however, subject to changes in contemporary tastes over the centuries.

The Sachsenhausen bridge tower also had a square floor plan and a pointed arched passage on the ground floor, but in the roof area it was reminiscent of Gothic patrician buildings of the time. Here he had a parapet walk with polygonal corner turrets that protruded over a round arch frieze. The top was formed by four pointed helmets and a hipped slate roof. At no time did he have picturesque jewelry, as far as is understandable. It was canceled in 1769. The Lange Franz , the larger tower of the new town hall, was built based on his model at the beginning of the 20th century .

On the north side of the Main there had been a closed wall between the Old Bridge and the Mainz Tower since the Staufer period, which could only be passed through six gates. The fisherman's gate , which was last rebuilt in 1449, was closest to the bridge . Its tower was demolished before the siege of 1552, so its appearance has not been passed down. The remaining tower stump showed a gable-like rising battlement above the passage opening. Between the gate and the bridge tower was a brick, triangular bulwark with numerous shooting holes and a bay window. The construction of this additional reinforcement probably falls in the year 1520, the exact demolition of the complex can no longer be determined.

The Metzgertor, which was connected to the west and was last rebuilt between 1456 and 1457, was at the exit of the butcher's quarter next to the slaughterhouse. Its square tower showed cuboids in the unplastered corners, had an ogival passage and three upper floors with two narrow rectangular windows each. The steeply hipped gable roof had a high bay window on the Main side. The gate and tower were demolished in October 1829 when a free port was to be built and the canvas house behind it was to be converted into a warehouse.

The Heilig-Geist-Pforte , built in 1454, was south of the Heilig-Geist-Spital on Saalgasse . Its square gate tower was slightly lower than that of the neighboring butcher's gate and had only two upper floors with rectangular windows above the ogival passage. But there was also a large bay window at the front of the gable roof. The tower was sold to the merchant Siebert for demolition in 1797 when he rebuilt the houses adjoining to the north in Saalgasse and built over the gate.

The main entrance on the banks of the Main was marked by the rent tower, completed in 1456, and the driving gate, completed in 1460 by the municipal works master and stonemason Eberhard Friedberger . While the rent tower has been completely preserved as part of the historical museum to this day , the drive gate was demolished in 1840. Only its richly sculptured oriel can still be seen on the western outside of the museum, a copy is on the south side of the new town hall.

The wooden gate received its final shape in 1456. The ogival passage had only a small height and was probably only intended for pedestrians. The tower rising above had only one upper floor, but a very steep gable roof with a polygonal bay window and pointed helmet end. Directly above the gate there was another Gothic bay window with tracery decorations and the carved date 1456. As a special feature, it was open at the bottom for communication and defense purposes. The gate was demolished in 1840.

Leonhardstor , which was also rebuilt in 1456, was the westernmost entrance to the city from the Main Quay . Like the wooden gate, it was a simple structure with only one floor. This was probably due to the fact that it was flanked by the mighty Leonhardsturm, which was built between 1388 and 1391 and in which the city stored important documents until the 17th century. With its four upper floors, the top of which protruded over a round arch frieze, and the conical roof with four oriels, the building was remotely reminiscent of the Eschenheim tower. The tower, which was built at the time to the reluctance of the Leonhard monastery, was demolished in 1808 and the gate in 1835.

The Mainzer Pforte closed off the main front and at the same time opened the western front of the land wall. The small width of the footbridge leading over the moat shows from the earliest illustrations that it was only ever used for pure passenger traffic. The originally Romanesque gate building from the time of the first city expansion was rebuilt from 1466 to 1467. The Mainz tower flanking it to the south, first mentioned in 1357, stood on a corner of the Main wall and the western city wall. It was designed as a massive, round tower with a crenellated crown protruding over an arched frieze and an open battlement. The top, octagonal floor had a bell-shaped roof with a lantern. In 1519 and 1520 the Mainz bulwark was reinforced in all directions by roundels, probably because of the threat of feud from Franz von Sickingen . After the cutting mills operated here , which received their water from a mill ditch from the Main, the vernacular also called this mighty bulwark of the city fortifications cutting wall .

The Schaumaintor on the Sachsenhausen bank got its name after it had been enlarged to accommodate the traffic from the closed Oppenheimer Pforte; previously it had also been called the Mainzer Pforte . The Ulrichstein, mentioned for the first time in a document in 1391, served to protect it, a strong round tower with a notched, conical helmet. When the Swedes withdrew in 1635, it was badly damaged. Its ruins remained in place after the Schaumain Gate was demolished in 1812 and only had to give way to road traffic in 1930.

Military importance

Shortly after its completion in the 16th century, the city wall was militarily and technically outdated again. It was designed as a medieval defense system for fighting with cutting and stabbing weapons, bows and crossbows. Since the 14th century, however, firearms, especially cannons, have revolutionized siege technology. At the latest, the storming of Constantinople in 1453, during which the strongest city wall in the world could be overcome with the help of huge cannons, marked a turning point here.

The fortifications of Frankfurt experienced their greatest test in July 1552. During the prince uprising, Protestant troops led by Moritz von Saxony besieged the likewise Protestant but loyal city for three weeks, which was successfully defended by troops of the Catholic emperor led by Colonel Konrad von Hanstein . Hanstein had the city fortifications brought up to date in a very short time, temporary bastions built up and the Gothic spiers of the Bockenheimer and Friedberger Tor thrown off so as not to stand in the way of their own artillery.

The siege ended with the conclusion of the Passau Treaty . It was the greatest military and diplomatic achievement in Frankfurt's history. The city had successfully defended its Lutheran creed and at the same time its privileges as a trade fair venue and as the place of election and coronation of the Roman emperors . From 1562 onwards, almost all emperors in Frankfurt were not only elected, as was customary before, but also ceremonially crowned.

The Landwehr

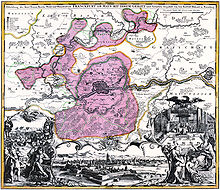

(copper engraving by Johann Baptist Homann , area boundaries corrected after Friedrich Bothe )

In the middle of the 14th century, at the time of the second city expansion , Frankfurt already had a sizable rural district. These included, clockwise to the right of the Main , the Riederfeld , the Friedberger Feld and the Galgenfeld , which roughly encompassed the area of the present-day districts of Ostend , Nordend , Westend , Gallus , Gutleutviertel and Bahnhofsviertel . To the left of the Main, ownership extended to the village of Sachsenhausen with its field mark along the Main and on the Sachsenhausen mountain. In 1372 the city acquired the Reichsschultheißenamt from Emperor Karl IV for 8,800 guilders , which made the city a Free Imperial City , and for a further 8,800 guilders the Frankfurt City Forest , a 4800 hectare area of the Reich Forest Dreieich . In addition, Frankfurt owned the village of Dortelweil an der Nidda and rights to the imperial villages Sulzbach and Soden . In 1367 the town of Burg and Dorf Bonames acquired Niedererlenbach in 1376 and the Goldstein farm in 1400 .

The battle of Eschborn

Despite the peace proclaimed by Charles IV, the Frankfurt possessions were constantly threatened, especially by the interests of the Kronberg knights and the Lords of Hanau , who wanted to put the aspiring imperial city of Frankfurt in its place. In 1380 the knights united in the Lion League , which the cities in the Second Rhenish League of Cities opposed. However, the Frankfurt attempt to secure his position by military force was unsuccessful. In the battle of Eschborn on May 14, 1389 , the city suffered a devastating defeat against Kronberg and its allies, the Hanauer, Hattsteiner and Reifenberger . 620 citizens, including some patricians and all the bakers, butchers, locksmiths and shoemakers in the city were captured. In order to release the prisoners and turn the war opponents into allies, Frankfurt had to use its ultima ratio . In a great effort, the city brought up a ransom of 73,000 guilders by March 1, 1393 , and appointed the knight Hartmut von Cronberg to be the bailiff of all urban villages, with his seat in Bonames and an annual salary of 184 guilders.

The construction of the Landwehr around the city

At the beginning of 1393 the plan of a Landwehr around the city appeared for the first time . In 1396/1397 the Landwehr was built from the Riederhöfen in the east to the Knoblauchshof in the north of the city. The city also built a wooden control room on each of the courtyards . The construction work aroused the displeasure of the neighbors in Vilbel and Hanau , so the council secured itself by acquiring a privilege on January 13, 1398 from the Roman-German King Wenzel , in which he allowed the city to protect itself in and around Frankfurt and Sachsenhausen as far as they wanted to dig trenches, military forces and waiting areas. In the same year the council resumed construction of the Landwehr and completed the north-western arch between Knoblauchshof and Gutleuthof on the Main .

The new Landwehr moved within a radius of about three to four kilometers around the city. Their course corresponded roughly to the political boundaries of the Free Imperial City. It consisted of a Gebück from impenetrable hedges with an upstream ditch. The western part of the Landwehr was later gradually added another trench.

Located between the city walls and the militia district consisted largely of agricultural land. Immediately in front of the city were gardens and vineyards, the outskirts around today's Alleenring were used according to a traditional land system based on medieval three-field farming. In addition, a wreath of fortified courtyards was drawn around the city. Part of the area was cultivated with summer grain, part with winter grain, while the third part lay fallow. In between there were smaller forest stretches and corridors such as the garlic field and the Friedberger Feld , which is important for the city's water supply and from which a wooden water pipe led to the Friedberger Tor since 1607.

The Sachsenhausen Landwehr

In 1413 the construction of the Sachsenhausen Landwehr began in the south of the suburb. In 1414, the Landwehr's first stone buildings were built with the gallows watch and the Sachsenhauser watch . These measures called another powerful opponent of the imperial city onto the scene. Werner von Falkenstein , Archbishop of Trier , Lord of Koenigstein and Count in the Hain , saw his feudal rights over the Wildbann Dreieich impaired by the construction of the Sachsenhausen Landwehr and the Waiting . However, the council relied on King Wenceslas' privilege and appealed to the German king and later Emperor Sigismund for help. Sigismund personally inspected the gallows watch and confirmed the Frankfurt privileges. Nevertheless, Archbishop Werner had the Sachsenhausen observation tower and the Sachsenhausen Landwehr destroyed in the spring of 1416. King Sigismund, who was in London at the time, admonished the bishop to make peace and the council to be patient until he came to Germany to make a decision. Only after Werner's death in 1418 did the council rebuild and complete the Landwehr from 1420 to 1429. The Bockenheimer Warte was built between 1434 and 1435, and a new Sachsenhausen observation tower in 1470/71.

Expansion of the Landwehr in the 15th century

In 1425 the city acquired the village of Oberrad , east of Sachsenhausen, which was included in the Landwehr in 1441. In 1474, after long efforts, the council succeeded in separating and acquiring Bornheim from the old judicial association of the Bornheimerberg county . In order to include the village in the Landwehr, considerable diplomatic preparations were necessary, as resistance was feared above all from the Hanau sovereign Philipp I of Hanau-Munzenberg . The council therefore had its landwehr privilege expressly confirmed without mentioning Bornheim in it.

On July 23 and 24, 1476, around 1,500 Frankfurt citizens and residents of the Frankfurt villages moved to the field in front of Bornheim in order to jointly dig the previously marked trench of the Landwehr. All 42 councilors were also present at the work. At the Knoblauchshof and Günthersburg, the council had set up guns and had brushwood posted to protect the work. With the construction of the new Bornheim Landwehr, the part of the Landwehr between Frankfurt and Bornheim became dispensable.

In 1478 the Bornheimer Landwehr was completed with the construction of the Friedberger Warte . The previous control room at the Knoblauchshof between Eschersheimer and Eckenheimer Landstrasse was abandoned as the traffic flows also changed. The traffic to Vilbel now ran via the Friedberger Warte, those to Ginnheim and Eschersheim via the Bockenheimer Warte.

The Landwehr was only passable on the five largest arterial roads. These passages were protected by waiting towers: on Mainzer Landstrasse the Galluswarte , on Bockenheimer Landstrasse the Bockenheimer Warte , on Friedberger Landstrasse the Friedberger Warte and on Darmstädter Landstrasse the Sachsenhausen observatory .

The two Riederhöfe served to protect the city limits on Hanauer Landstrasse . Whoever wanted to cross this border had to pass three iron strikes . Despite a contract from 1481, there were constant border disputes with the Hanauers, who occupied the Reich Chamber of Commerce until it was dissolved. On March 26, 1605, 300 men from Hanau's troops devastated the outer rains and maltreated the Frankfurt guards, who were barely able to give warning signals with horns and rifles. It is reported from 1675 that Frankfurt dug a Hanau border post , removed the Hanau coat of arms from it, sawed the stick into pieces and chopped the latter into small pieces . It was not until 1785 that the demarcation was finally regulated in a contract.

The Eschersheimer Landstrasse had not been passable since 1462. The iron strike at the passage through the Landwehr was normally closed. Only the Niederurseler Müller and the mayors of the Frankfurt villages owned a key. Plans to build a new control room were never carried out. Only in 1779 did the people of Eschersheim receive a key for the Iron Strike at their request.

In the 16th century the military use of the Landwehr was tried out several times. In 1517 Franz von Sickingen attacked a convoy in front of the Galgentor during the autumn fair within the Landwehr and took seven freight wagons away from the Frankfurters. During the Schmalkaldic War, the troops of the Schmalkaldic League defending Frankfurt fought back several attacks by imperial troops on the Landwehr at the Galgenwarte, the Bockenheimer and Friedberger Warte from August 28 to 30, 1546.

During the siege of Frankfurt in July 1552, however, the Landwehr was not up to the attacks. With the first attack, the troops of the Elector of Saxony broke through the Landwehr at the Friedberger Warte, destroyed the Galgenwarte and the Sachsenhausen observation point, stole 3,000 head of cattle and set up camp right in front of the city wall. The street names Im Sachsenlager and Im Trutz Frankfurt in the Westend still remind us of this today .

Although the Landwehr and the destroyed control rooms were rebuilt after the Allies withdrew, they no longer played a role in the wars of the 17th and 18th centuries. The gradual dismantling of the fortifications began in 1785 and continued until 1810.

The baroque city fortifications

After the siege of 1552, which was successfully passed, more than 50 years passed, during which Frankfurt was spared from military threats and had no reason to attempt to strengthen its fortifications. Even warnings from some war experienced personalities to better protect the city were unable to induce the council to take greater measures.

The fact that Frankfurt got off so lightly was not due to its fortification, which was already backward at the time. The decisive factor was rather the resolute defense by numerous artillery pieces, which the inadequate fire control of the besiegers had nothing to counteract. The second half of the 16th century brought the final breakthrough for what were then known as powder guns. They made stone fortifications of the Middle Ages obsolete, but also required the construction of works for defense purposes that were suitable for setting up guns, so-called bastions or roundels. With these, the existing medieval city wall in Frankfurt am Main was strengthened selectively during and after the siege of 1552. In addition, the provisional rubble from the time of the siege had been consolidated and expanded in places, e.g. B. on the so-called Judeneck south of the All Saints gate.

But in the end, this would not have been enough to effectively defend the entire city wall in an emergency. Due to the numerous wars in Italy , a new fortification theory had emerged as early as the end of the 15th century. Experience taught that straight works served the defense better than half-round ones. After a few intermediate steps, one saw pentagonal bastions , also known as bulwarks, as an ideal shape, which were connected to one another by intermediate walls ( curtains ).

( copper engraving by Matthäus Merian the Elder)

Outbreak of the Thirty Years War

The Great War began with the unrest in Bohemia in 1618 . But it was not until the death of Emperor Matthias in 1619 that the political situation deteriorated dramatically. In the same year, this prompted the council to contact Adam Stapf, an engineer from the Electoral Palatinate who was involved in fortress construction in Mannheim. He presented the city with a plan estimated at 149,000 guilders. According to this, 13 hollow bastions were to be built north and five south of the Main. In order to save further costs, it was planned, instead of curtains, to fill the back of the old kennel wall with earth and use it as a parapet . The council immediately refused, pointing out that the costs were too high, but in view of the growing threat it felt compelled to get in touch with Stapf again as early as 1621.

The engineer now working in Heidelberg immediately submitted a new draft. After that, the medieval fortifications were to remain untouched, and a completely new fortification system with 13 bastions and 12 curtains was to be built at some distance from the city. Stapf estimated the cost of execution at 159,600 guilders. At the meeting on May 10, 1621, the city council took the view that the war would soon be over and that it would be better to refrain from the extensive work because of the enormous costs.

It soon became clear that the war could also reach Frankfurt: In the battle of Höchst on June 20, 1622, over 40,000 soldiers from the Protestant Union and the Catholic League faced each other in the immediate vicinity of the city . After the retreat of the Protestant troops, the imperial city was forced to be generous towards the Catholic victors. In order to preserve its Lutheran creed and the imperial privileges in equal measure, and to keep the war fury at the gates, the city began a policy of benevolent neutrality on all sides, with no firm alliances. Although the most important weapon in this strategy game was the well-filled city bag, one wanted to demonstrate military strength for safety.

In the same year, Eberhard Burck , engineer and master builder in Gießen , was hired for an initial two years to expand the fortifications. On his recommendation, the council also hired Steffan Krepel von Forchheim to serve as Wallmeister for an initial year. According to Burck's plan, which was apparently geared towards cost savings, Frankfurt was to have six bastions and Sachsenhausen only three; In January 1624 Burck asked for a compensation for his design, and Krepel complained that he was not earning anything because the work was not going to begin. Ultimately, only Burck's proposal was made to secure the east side of Sachsenhausen with a roundabout. Because of further delays on the part of the council, a dispute broke out in mid-1624, which ended with Burck's dismissal and payment of 125 thalers in severance payment in February 1625.

The commissioning of Johann Wilhelm Dilich

The council's intention to expand the city fortifications had meanwhile got around. The famous fortress builder Johann Wilhelm Dilich , who was then active in Kassel , offered his services in a letter dated December 16, 1624. At the same time he submitted a commented draft in which he emphasized above all that he did not consider the old city wall strong enough to serve as an intermediate wall for the bastions to be built. Because of a supposed calming of the war events, the council did not respond to it again. When Wallenstein's army left Bohemia for Franconia and Hesse in June 1625 , the city schoolmaster, Johann Martin Baur von Eysseneck , brought up Johann Adolf von Holzhausen , who was born in Frankfurt, as a fortress builder and who had been captain in Mannheim .

The council immediately put Captain von Holzhausen into his service and charged him with securing the Friedberger Tor, which had long been seen as the weakest point in the city's defense. The terrain rose here, and the gate stood at a jutting corner of the city wall, to which a dam led across the moat. In an emergency, this would not have been flanked. Holzhausen submitted a draft for the construction of a ravelin , i.e. an independent bastion in front of the city gate. Work began at the end of July 1626, but grievances soon became apparent as a result of the captain's lack of expertise. As Dilich suspected, the fence wall was too weak to build a parapet behind it. Now parts of the wall had fallen into the city moat after being filled up. In the other direction the earth had buried adjacent gardens to the south, whose owners complained.

After a tip from the printer Clement Schleich from Wittenberg , the council turned to Dilich's father, the electoral Saxon engineer Wilhelm Dilich . He and his son arrived in January 1627 to get an idea of the situation. In his report , like his son, he rejected any inclusion of the old city fortifications and recommended, similar to Stapf, a regular circular fortification with some distance from the city. In terms of planning, this would have been the simplest variant, as all the bastions and the connecting curtains would have been of the same size. For the city, however, it would have meant the acquisition of field goods in addition to the still considerable costs. The council refused and asked for four other variants with a fortification wreath placed closer to the city to be submitted. These too were all too expensive for the city leaders, and so father and son prepared for departure again at the beginning of April.

When the Ravelin built by Holzhausen collapsed in mid-1627, the apparently desperate fortress builder called the council to entrust Johann Wilhelm Dilich with the task. By the time Dilich arrived in October, Holzhausen did even more damage than good by having the earth of the collapsed plant filled up at the level of the pestilence house behind the city wall. Again several gardens were severely damaged as a result.

Dilich, who had gotten an overview in the winter months, was appointed to the city services as an engineer and piece major on January 8, 1628 . At the Council meeting on February 22nd, there was an extremely controversial debate about his plans to significantly expand the defenses. Despite an ultimately again negative attitude, there was still the problem of the unsuccessful Holzhausen plant on either side of the city wall, estimated at 3000 carts of earth. More out of hopelessness than determination, Dilich was given permission to strengthen the old city wall with the earth of the collapsed Ravelin at its weakest points in the north of the city with two bulwarks in front of the Eschenheimer Tor and the Friedberger Tor. In order to secure the project politically, city councilor Johann Martin Baur von Eysseneck solemnly declared at the laying of the foundation stone on June 16, 1628 that the new fortification was not directed against the emperor and the empire, but only served to protect the city loyal to the emperor.

Further false thrift on the part of the council led again to the collapse of larger parts of the facility under construction in mid-1629. Because of the view that the Friedberger Tor had to be secured first, Dilich was forced to build the first bulwark there instead of starting the fortification at the deepest point of the city on the Main bank, as the drainage of the water would have required. In order to protect the field goods, he should also build on the old, completely boggy ditch, which led to static problems and ultimately to collapse. In the following investigation, Dilich, the Mannheim Wallmaster Nikolaus Mattheys , who was hired on his recommendation, and the executing workers blamed each other. So Wall Master had some more beer hut as the rampart awarded the artisans had Dilich angeschnarcht . Ultimately only Mattheys was dismissed and replaced by Johann Zimmermann from Mainz . The craftsmen could not be proven guilty, and the council stuck to Dilich too.

Again an expert, now the Ulm fortress builder and mathematician Johannes Faulhaber, was called in . He discovered the already known, but also new, constructive mistakes, corrected Dilich's plans to remedy them and openly snubbed the same before the council that his father had done better, but the son did not want to learn anything more and stick to his own opinion . Faulhaber was able to afford this criticism, however, as he provided powerful evidence for the correctness of his statements through algebraic calculations and a paper model. Ultimately, after Faulhaber's departure in March 1630, Dilich followed his recommendations, so that the work made good progress from this point on. The damage caused by the collapse had already been restored in June.

At times up to 600 men worked on the fortress construction. In 1631 Dilich was assigned the Darmstadt master builder Matthias Staudt as an assistant. The citizenry had to raise an extraordinary estimate , i.e. a special tax, for the construction of the fortress and was also obliged to perform labor. The teachers at the municipal high school also had to lend a hand; a petition to the council in which they asked for exemption from entrenchment work, since they meditate day and night and, in addition to their poorly paid teaching activities, also negociate , i.e. have to do business in order to earn a living, was refused. While Dilich, as an engineer, received an annual municipal salary of 448 guilders, the high school teachers only received 50.

The fortress construction

Dilich applied a further development of the Italian construction method from the Netherlands , the Dutch fortress architecture . He left the old walls in place, but dug new trenches about 30 meters in front of the existing structures, which he used to dig a new wall in front of the wall. In some cases he filled in the old trenches in front of the wall, and in others he dug a new one in front of the old one. The advantage over the Italian method was that the ramparts were not climbed because of the trenches, and cannon pellets in earth walls (compared to the stone ramparts of the Italian style) could not cause great damage by flying debris and splinters. A hand drawing by Dilich shows his method of construction: the kennel running along the inside of the wall, the city wall with the battlements, in front of it the piled-up rampart , the fortified parapet , at the foot of which the Faussebraye with another parapet, then the escarpe stretched from the inside to the outside , the wet ditch, the Contrescarpe and finally some with picket occupied Glacis . From the pentagonal bastions one could coat the glacis and the wall fronts with guns.

However, such as B. shows a general view of Matthäus Merian from the year 1645, built only from the Eschenheimer Tor to shortly before the Allerheiligentor. Due to the bad experiences that had been made while building on the old city moat, the line of the new works was immediately shifted around 15 meters further outwards. As a result, the entire medieval city wall with its moat behind it was ultimately preserved. On the other hand, this had the advantage that the defenses in this area were surrounded by water on both sides and could only be reached through the few bridges of the land gates.

In December 1631, Dilich was supposed to stop the work for the time being on the advice of the council due to lack of money. After the Swedes invaded Frankfurt under King Gustav II Adolf on November 20 , they soon got the work going again. The Swedish city commandant, Colonel Vitzthum , let his soldiers take part in the fortification work. From May 1632 three other strongholds emerged: The one at widths Wall was also Sweden bulwark called because it was built by the Swedish soldiers. The farmers from the Frankfurt villages who were obliged to do compulsory labor built the farmers' bulwark at Eschenheimer Tor, and the Frankfurt city military built the Bockenheimer bulwark at Bockenheimer Tor.

After the news spread that the imperial army was approaching, three more bulwarks were started in August of that year. Under pressure from the Swedes, the council decided that two citizens' quarters and 150 Jewish residents should be used for this every day. The presence of the military now also had an impact on the organization: by means of a drummer, the citizens were summoned to the house of the citizen captain early in the morning in the quarters that had their turn . With the beating of the drums and a flag carried forward, they went to work. In order not to have to work themselves, many richer citizens sent servants or maidservants to perform dances to the sound of the drum. This displeased the Swedish military, but the council did not forbid it in order to keep the servants happy and willing to work .

The further expansion of the fortifications dragged on long after the Peace of Westphalia . The digging of the trenches and the basic construction of the bulwarks and curtains were largely completed by 1645. In the following years, the main focus was on building the outer lining wall of the trench and filling up the field brimstone. The latter in particular dragged on enormously with the resources of the time. After Dilich died in 1660, the play major Andreas Kiesser continued the work. In 1667, after 49 years, the work was essentially complete. To the north of the Main, a total of 11 bastions now stretched around the entire city, while the much smaller Sachsenhausen was fortified with five bastions. For the first time the Fischerfeld was included in the city fortifications.

The 11 bastions were called from east to west: Fischerfeldbollwerk (begun in 1632), Allerheiligen or Judenbollwerk (at Allerheiligentor, begun in 1632), Schwedenschanze or Breitwallbollwerk (begun in 1632), Pestilenzbollwerk (on Klapperfeld, where the Pestilenzhaus was then and now the Frankfurt Regional Court Main located, started in 1631), Friedberger Bollwerk (at Friedberger Tor, started 1628), Eschenheimer Bollwerk (at Eschenheimer Tor, started in 1631), Bauernbollwerk (started in 1632), Bockenheimer Bollwerk (at Bockenheimer Tor, started in 1632), Jungwall Bollwerk (started in 1632 ), Gallows bulwark (begun in 1635) and Mainz or Schneidwall bulwark (begun in 1635, almost completely rebuilt between 1663 and 1664 due to severe structural damage).

The zoo bulwark on the eastern bank of the Main (started in 1635), the high plant on the southeast corner (started in 1648, brought into its final form in 1665), the hornworks on the Affentor (1631 to 1635, initially built as a demi-lune , 1665 to 1666 ) moved around Sachsenhausen in its final form), the Oppenheim bulwark west of the former Oppenheimer gate (no exact details available, probably built around 1635 as a demi-lune and later reinforced) and the Schaumainkai bulwark (started in 1639 as a demi-lune and finished in 1667 in his final shape) at the Schaumainkai .

Since the bastions were partly piled up directly in front of the old exits of the country gates, these also had to be changed or rebuilt. In summary, it is noticeable here that the new buildings, largely in the early Baroque style, were rather plain. One possible explanation is that the pure engineering work on the bastion was so stressful for the city that there was simply no money for elaborate, representative gate structures. The Galgentor was retained in its medieval form and was soon given the name Old Galgentor after the New Galgentor was built further south between the Gallows Bulwark and the Mainz Bulwark from 1661 to 1662 . Access was made possible by a drawbridge over the new city moat.

At the Bockenheimer Tor, which had already been changed in 1605, nothing changed; the bridge over the new city moat was simply extended to provide access. Although not absolutely necessary due to the lack of a bastion erected in front of it, the Eschenheimer Tor also received new gateways from 1632 to 1633, which on the whole were probably the most representative. These had very lively volute gables , the windows, like the gates, had rich profiles, of which the foremost between antique acroteria showed an imperial eagle . On the other hand, the old Friedberger Tor was destroyed because of the bastion of the same name that was built directly in front of it and was only preserved as a wall tower. The New Friedberger Tor , whose structural design can best be compared to the Galgentor, was built between 1628 and 1630 at the northeast end of Vilbeler Gasse (today's Vilbeler Straße). Finally, the All Saints' Gate was moved to the north by means of a new building erected in 1636, after the old gate building only formed an entrance to the bulwark of the same name.

Consequences of the Thirty Years War

The benefits of the fortifications for Frankfurt are difficult to assess. Its construction took a heavy toll on the city's finances. Despite the fortifications, Frankfurt was occupied by Swedish troops from 1631 to 1635. Tensions, which were latent all along, culminated on August 1, 1635 when Swedish troops tried to take control of the city from Sachsenhausen.

Thereupon the council in turn let in the imperial troops under Baron Guillaume de Lamboy on the north side of the Main. Entrenched in both parts of the city, heavy fighting broke out and caused considerable damage. Among other things, the bridge mill and almost the entire Löhergasse in Sachsenhausen was destroyed. It is only thanks to Vizthum's insight, who immediately entered into negotiations with Lamboy, that the catastrophe, a major fire devastating the entire city, could just be averted. On August 10, as a result of the talks, the Swedes were granted a withdrawal with military honors towards Gustavsburg .

The plague years from 1634 to 1636 left particularly severe devastation. In 1634 3512 people died, 1635 3421 and 1636 even 6943 in Frankfurt. The city population has never been higher than 10,000 to 13,000 people since the Middle Ages, so that the high mortality can only be explained by the people from the surrounding area who had fled to the city from the horrors of war. Despite all the burdens, Frankfurt, in contrast to other southern German cities such as Mainz or Nuremberg , retained its political importance and quickly recovered from its economic consequences after the war.

Planning errors and structural damage

Even during the ongoing construction work, but especially towards the end of the 17th and 18th centuries, damage to individual fortifications occurred again and again, which had to be repaired at great expense. Even after 1667, the city's arithmetic books recorded hardly a year in which the fortification building item did not accumulate at least to several thousand, but often well over ten thousand guilders. The need for repairs was almost always based on mistakes made in building it. Consideration of the field goods necessary to build the fortress as well as false economy were the reason that the building projects were not carried out with the necessary generosity, but rather petty and, moreover, in the wrong place.

One of the main mistakes in the early years is that the construction of the baroque fortifications did not begin at the deepest point of the urban area on the lower bank of the Main, where the incoming water could easily have been drained off. As a result, the foundations of almost all bulwarks were laid on much too damp ground, which led to structural damage, but above all was hardly completely repairable. In addition, there was the apparently inadequate technical knowledge of all those involved in terms of the fundamental strength of the foundations. After all, while Swedish troops were present, construction was carried out at too great a speed.

In addition, the council repeatedly suppressed the amount demanded by the engineers, so that the careful craftsmanship inevitably suffered. In addition, there was apparently not a single person among the councilors throughout the 17th century with the necessary skills to judge the quality of the work. The frequent calls to reviewers are a testament to this. However, none of the experts, of whom Faulhaber was undoubtedly the most capable, noticed the fundamental flaw in the whole system. The shoulders of the bastions were perpendicular to the partition wall, so they formed a right instead of an obtuse angle. As a result, in an emergency it would not have been possible to cross the trenches in front of their tops. Equally flawed was the construction of ridges in front of the tops of the bulwarks instead of in front of the middle of the intermediate walls. As in 1552, the resulting blind spots would have been fired at z. B. from Mühlberg or the height of the Affenstein , without a defense from the city would have been possible.

In the course of the 18th century, the city fortifications finally lost their military value due to rapid military progress. Instead, the urban population began to use the publicly accessible ramparts as a recreational area. The first linden trees were planted on the ramparts around 1705 and from 1765 a continuous avenue (Lustallee) led around Frankfurt and Sachsenhausen.

During the Seven Years' War , the city was occupied by French troops and made significant contributions . Even in the coalition wars, the city fortifications no longer offered protection, but even turned out to be dangerous, as a defended city was exposed to the danger of being shot at.

The demolition of the city fortifications in the 19th century

Occupation of the city and first steps by 1806

In October 1792 French troops occupied the city, but they were driven out again on December 2nd. But even the expulsion was indicative of the uselessness of the fortification, as the allied Hesse and Prussians were able to storm Friedberger Tor almost unhindered . In 1795 and 1796, enemy troops again moved in front of the city. The French bombardment of the city, which was defended by Austrian troops on July 13 and 14, 1796, caused great damage, one third of the Judengasse , which was only destroyed by a major fire in 1721 , was again destroyed.

As a result, the city's senate decided in 1802 to draw up plans to demolish the fortifications. The impetus to remove the fortification came from outside, though certainly not entirely unselfishly. The French government had pointed out through the Frankfurt ambassador in Paris that the city would be defused as a means of protecting the city from misuse as a weapon station and base in future wars. Frankfurt, like the remaining six imperial cities, was assured of neutrality in the event of war at the Reichsdeputationstag in Regensburg . In the Senate, however, there was fear that this recommendation could be made a requirement if war broke out, which was ultimately the trigger for initial measures.

As had been the case almost two centuries before, the plans for the softening dragged on over a long period of time, and the Senate had a large number of models calculated. Many only intended to remove the bulwarks while retaining the 14th century city wall for civil custody . As with the early modern fortifications, the politicians' view of the much too high costs were the main reason why an overall plan did not come about. In 1804, after almost 20 months of discussions, the demolition began, but the work with 50 to 60 day laborers was only carried out half-heartedly. An appraisal from the summer of 1805 stated that if the pace of work was continued, at least another nine years could be expected for complete softening.

Fürstprimas Dalberg and the commissioning of Guiollett

Only after the re-occupation of Frankfurt by French troops in January 1806 did the project move again. At the same time, a call by the Senate to the citizens to participate in the demolition fell on unexpectedly fertile ground, probably also in view of the danger posed by the acute Austro-French war. After the end of the Holy Roman Empire in August 1806, the Free Imperial City of Frankfurt lost its independence. It was added to the territory of the Prince-Primate Carl Theodor von Dalberg .

On behalf of Dalberg, Jakob Guiollett wrote a memorandum on the demolition of local fortifications , which appeared on November 5, 1806. In it he suggested demolishing the fortified belt of Frankfurt and replacing the bulwarks with a promenade and an English landscape garden , which is now known as ramparts . On January 5, 1807, the prince appointed him Princely Commissarius in the local fortress construction demolition business .

Guiollett called in the Aschaffenburg palace gardener Sebastian Rinz to plan the work. In the following years the Bockenheimer Anlage (1806), Eschenheimer Anlage (1807), Friedberger Anlage (1808/1809) and the Taunus and Gallusanlage (1810) were built. The demolition of the mighty Mainz bulwark , which lasted from 1809 to 1818, was particularly costly . The Untermainanlage and Neue Mainzer Strasse were built on the site in 1811 . In 1812, Rinz completed work on the Obermainanlage . All fortifications except for the Sachsenhausen cowherd tower and the Eschenheim tower were laid down, only some of the gates on the banks of the Main from the 15th century, including the mighty Fahrtor , remained in place for the time being. They were only demolished in 1840 when the bank of the Main was raised by two meters.

The citizens saw the demolition of the old walls as a sign of a turning point. Catharina Elisabeth Goethe wrote enthusiastically to her son on July 1, 1808 : “The old walls have been demolished, the old gates torn down, a park around the whole city, one believes it is Feerrey. The old wigs would not have been able to do this until Judgment Day. ” The much younger Bettina von Arnim , who was already under the influence of romanticism , expressed herself rather sadly : “ Many a Frankfurt citizen child will feel like me that he is cold and it's eerie, as if his wool had been shorn off in the middle of winter. "

In 1813 the French troops, on their retreat after the lost Battle of Leipzig, devastated the ramparts that had just been built. Guiollett, who has meanwhile been appointed Prefectural Council for the Grand-Ducal Department of Frankfurt and Mayor of Frankfurt, had the facilities restored immediately by city gardener Rinz. After the Free City of Frankfurt regained its independence in 1816, it protected its new green belt against development in 1827 with a wall service .

Instead of the demolished gates, city architect Johann Georg Christian Hess built classicist gate structures with wrought-iron bars from 1807 to 1812 , which were locked every evening until 1864. Not all gates were built from scratch. At the Galgentor and the Eschenheimer Tor, as can be seen from contemporary images, the early baroque outer gates were included. Nevertheless, most of them were torn down again by the end of the 19th century.

Parts still preserved today

Due to the Wall Service, the ramparts have remained largely untouched to this day and still shape the Frankfurt cityscape. Eight of the former 11 bulwarks can still be seen in the course of the ring road , only the first demolished gallows bulwark and the two half bastions located directly on the Main bank, the Fischerfeld bulwark and the Mainz bulwark disappeared completely. The only structures of the disappeared fortifications are the Rechneigrabenweiher in the Obermainanlage, the pond in the Bockenheimer Anlage and the mound of the former Junghof bulwark in the Taunusanlage. An equestrian statue of Kaiser Wilhelm I by Clemens Buscher has stood on this hill since 1896 , which was melted down in 1941 as a metal donation from the German people . The Beethoven monument , Georg Kolbe's last work, has been located here since 1948 .

During civil engineering work in the Bockenheim facility in 2008, the remains of the base of the city wall were re-excavated, which have to give way to an urban building project. In September 2009, during excavation work on Bleichstrasse, an approximately 90 meter long section of a casemate from the 17th century was rediscovered and uncovered, which presumably had belonged to the Friedberg bastion.

Remnants of the Main Wall were incorporated into the quay wall between the Obermainbrücke and the Alter Brücke, the parts used can be recognized by the loopholes in them. When building the high quay below the Untermainbrücke , stones from the former Mainz bulwark were used. Today only the cowherd's tower reminds of the former Sachsenhausen fortress ring . On the other side of the Main, the Eschenheimer Tower is the only tower that has been preserved for the landward fortification, and the Rententurm at the Fahrtor on the Main . The classicist gate buildings of the early 19th century have disappeared from the cityscape with the exception of the two monkey gate houses in Sachsenhausen.

After the road breakthroughs and demolitions in the 19th century, a remnant of about 75 meters with 15 blind arches extending to the tramline was preserved. It was part of a section that was renewed after the Great Christian Fire of 1719. The new baroque buildings that were built there used it as a fire wall so that the section of the wall was not accessible to the public. The town houses on Einhornplatz in Fahrgasse, shortly before they crossed Töngesgasse , formed tiny backyards with the wall, which were also accessible through a complicated system of passageways and passageways, but were unknown even to most historians. Only after the destruction of the old town in 1944 was the section of the wall exposed and has been preserved to this day. The street section behind it, called An der Staufenmauer , with functional buildings from the 1950s, is to be redesigned in the near future according to plans by several factions in Frankfurt's Römer with a view to the historical significance of the place.

The floor plans of the houses between Fronhofstrasse and Wollgraben and between Fahrgasse and Hinter der Schöne Aussicht also showed the course of the Wall, which was over 700 years old, until the Second World War, although almost all of them had been rebuilt in the classicist style. Presumably, the parcels had not been changed when the Fischerfeld was built at the beginning of the 19th century due to traditional ownership. As a result of the reconstruction ignoring the historical street layout and the breakthrough in Kurt-Schumacher-Straße, this reference to the Staufen wall has also completely disappeared. Another remnant of the fortification can still be seen on the Liebfrauenberg in the west facade of the Liebfrauenkirche .

Today there are no more traces of the north Main Landwehr, of the Sachsenhausen Landwehr there are still ditches and ramparts between Wendelsweg and Viehweg. In addition, three streets, the Sachsenhäuser , the Oberräder and the Bornheimer Landwehrweg, remind of the former fortifications. In addition, the four control rooms have been preserved in the cityscape, the towers of which have served as ventilation shafts for the Frankfurt alluvial sewer system since the 1880s. Two of them, the Friedberger Warte and the Sachsenhäuser Warte, are accessible to the public through gastronomic use.

The Romanesque mansion of the Großer Riederhof was one of the oldest secular buildings still preserved in Frankfurt in the early 20th century, which, according to recent comparative research, was probably built at the same time as the Saalhof, perhaps even under the same master builders, around the mid-12th century. At Emil Padjera’s instigation, the planned street layout of Hanauer Landstrasse was changed shortly after 1900 in order to prevent its demolition, which was an absolute rarity at that time. The house burned down in the air raids in 1944 and the ruins were torn down after the war. Today only the Gothic gate building on Hanauer Landstrasse and the street name An den Riederhöfen in Ostend remind of the courtyard. They mark the former eastern extension of the Landwehr.

See also

literature

- Architects & Engineers Association (Ed.): Frankfurt am Main and its buildings . Self-published by the association, Frankfurt am Main 1886 ( digitized - Internet Archive ).

- Friedrich Bothe : History of the city of Frankfurt am Main . Verlag Wolfgang Weidlich, Frankfurt am Main 1977. ISBN 3-8035-8920-7 .

- Elmar Brohl : Fortresses in Hessen. Published by the German Society for Fortress Research e. V., Wesel, Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 2013 (= Deutsche Festungen 2), ISBN 978-3-7954-2534-0 , pp. 73-76.

- August von Cohausen: Contributions to the history of the fortification of Frankfurt in the Middle Ages . In: Archive for Frankfurt's History and Art . Volume 12, self-published by the Association for History and Antiquity, Frankfurt am Main 1869.

- Walter Gerteis: The unknown Frankfurt . 8th edition. Verlag Frankfurter Bücher, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-920346-05-X .

- Rudolf Jung : The laying down of the fortifications in Frankfurt am Main 1802–1807 . In: Archive for Frankfurt's History and Art . Volume 30, self-published by the Association for History and Antiquity, Frankfurt am Main 1913.

- Fried Lübbecke : The face of the city. According to Frankfurt's plans by Faber, Merian and Delkeskamp. 1552-1864 . Waldemar Kramer publishing house, Frankfurt am Main 1952.

- Ernst Mack: From the Stone Age to the Staufer City. The early history of Frankfurt am Main . Knecht, Frankfurt am Main 1994. ISBN 3-7820-0685-2 .

- Emil Padjera: The bastionary fortification of Frankfurt a. M. In: Archive for Frankfurt's history and art . Volume 31, self-published by the Association for History and Antiquity, Frankfurt am Main 1920.

- Eduard Pelissier : The Landwehr of the Imperial City of Frankfurt am Main. Topographical-historical investigation . Völcker, Frankfurt am Main 1905.

- Martin Romeiss: The defense constitution of the city of Frankfurt am Main in the Middle Ages . In: Archive for Frankfurt's History and Art . Volume 41, Waldemar Kramer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1953.

- Heinrich Schüßler: Frankfurt's towers and gates . Waldemar Kramer publishing house, Frankfurt am Main 1951.

- Christian Ludwig Thomas: The first city wall of Frankfurt a. Main . In: Report on the progress of Roman-Germanic research . Volume 1, published by Joseph Baer, Frankfurt am Main 1904.

- Christian Ludwig Thomas: The northwestern train of the first city wall of Frankfurt a. M. In: Individual research on art a. Antiquities to Frankfurt am Main . Volume 1 (no longer published), published by Joseph Baer, Frankfurt am Main 1908.