Hayn Castle

| Hayn Castle | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Hayn castle ruins today |

||

| Alternative name (s): | Grove, Dreieichenhain | |

| Creation time : | around 1080 | |

| Castle type : | Niederungsburg, location | |

| Conservation status: | Enclosing walls | |

| Standing position : | Nobles | |

| Place: | Dreieichenhain | |

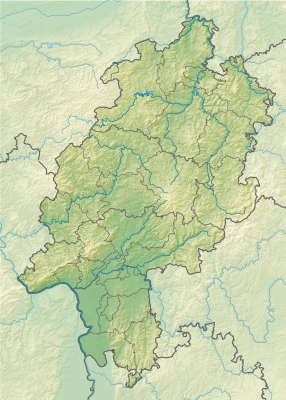

| Geographical location | 50 ° 0 '5 " N , 8 ° 42' 59" E | |

|

|

||

The Burg Hayn , also Hain or Dreieichenhain called, is the high medieval ruin a lowland castle ( tower castle ) in Dreieichenhain , a district of the Hessian town of Dreieich , in the Offenbach district .

history

The castle was the seat of the Reichs vögte , who administered the Dreieich Wildbann from here on behalf of the emperor .

Emergence

According to legend, the old hunting lodge, the predecessor of the castle, was founded by Charlemagne . He is said to have liked the Hengstbach valley so much that he decided to build his hunting lodge here. Karl's fourth wife Fastrada is said to have owned a magic ring and sunk it here in the castle pond. The emperor was thus magically tied to this hunting lodge in the grove and made it his favorite hunting spot.

According to older tradition, there was a simple hunting lodge from the 9th century as the center of the Dreieich wilderness forest in today's Dreieichenhain , which is said to have been expanded into a royal hunting lodge of stone buildings with a protective moat around 950. The early dating to the 9th and 10th centuries is now disputed in recent scientific research and it is assumed that it originated in the time of the Salians , i.e. in the first half of the 11th century.

The Königs- und Vogthof, surrounded by a moat, consisted of several stone buildings, horse and dog stables and a (probably) two-story mansion that served the king as accommodation. The king and his entourage stayed here to hunt.

Hagen-Munzenberg

A document mentions Eberhard von Hagen in 1076 , the first Vogt of Dreieich and close confidante of Emperor Heinrich IV. When he took over his Vogtamt, Eberhard and later his descendants named themselves after the Hagen hunting lodge . Hagen means something like "enclosed courtyard" in Old High German. The office and castle were given as fiefdoms to von Hagen-Münzenberg .

Eberhard von Hagen built a five-storey residential tower on a small island (30 × 40 m) in the Hengstbach am Jagdhof around 1080 . In the basement, the residential tower had a wall thickness of 2.80 m on an area of 12.50 × 13.20 m, was approx. 25 m high and surrounded by a high circular wall and a wide moat .

The complex, which has become the family seat of the influential lords of Hagen-Münzenberg, was expanded at the end of the 12th century, during the reign of the Hohenstaufen family . The residential tower was included in the castle wall. There were also a round keep , a Romanesque palace and the Holy Pankratius consecrated chapel . The castle wall was surrounded by a wide moat. Protection was guaranteed by castle men , whose riders stood outside the castle. A Fronhof (today Restaurant Faselstall) with kennels for hunting dogs was built next to the castle. Dreieichenhain was therefore ironically referred to as "The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation dog stable" . A city wall with ramparts and moats enclosed the emerging city. The Romanesque city gate - the later central gate, no longer exists today - was the only access to the castle and city.

Munzenberg inheritance

With the extinction of the Lords of Hagen-Münzenberg in 1255, the Munzenberg inheritance followed . The castle was administered jointly by several heirs and thus became a Ganerbeburg . Until 1286 the Lords of Falkenstein were able to take over five sixths of the castle, one sixth remained with Hanau . The castle was expanded in the following period. The hall and the church were enlarged, a small school and the Burgmannenhaus of the Bellersheim were built. A mighty gate tower secured access to the castle.

From 1256 the place Hayn is documented, which developed around the castle. Mainly Wildbann servants lived here.

In 1418 the Falkensteiners died out. After an inheritance was divided, their share went to the Lords of Isenburg and Sayn . In 1460 the Salian residential tower burned down. Count Ludwig II of Isenburg acquired Sayn's share in the castle in 1486. Further renovations gave the castle a late Gothic look, but was then given up as a residence.

Modern times

The Hanau share of one sixth was exchanged in 1701 with Isenburg for a third from Dudenhofen , so that the castle now belonged entirely to the Isenburg family. In the 18th century it was used as a quarry. The now sole owner of the castle, the Count of Isenburg-Philippseich , was able to temporarily prevent further demolition of the castle after a six-year legal dispute. In 1750 the residential tower collapsed. Only one wall (22 m) remained. In 1773 the church of the Huguenot settlement of Neu-Isenburg , founded by the Counts of Isenburg, was also built from the ruins of the tower block. Stones from the hall and keep were used for road construction at the end of the 18th century.

In 1816 the small Isenburg state, which had meanwhile advanced to a principality, fell to the Grand Duchy of Hesse . The castle ruins of Hayn fell into the private fortune of the princes during the property dispute between Isenburg and the Grand Duchy. The Isenburg residents sold the castle in 1931 to the Dreieichenhain eV history and homeland association

Cultural monument

The castle complex is a cultural monument according to the Hessian Monument Protection Act . The remains of the residential tower are among the best preserved secular buildings from the Salier period in Germany .

The Palas and keep still exist. The west wall of the tower castle in connection with the castle garden of the complex serves as a backdrop for the castle festival, which has existed since 1924. In the castle there is a local history museum ("Dreieich Museum").

At the site of today's castle church, there were initially smaller chapels, and finally an early Gothic hall church rebuilt around 1300. This burned down on December 27, 1669. The castle church, consecrated on the first Advent in 1718, will be renovated for the 300th anniversary and a sacristy will be added.

literature

- Roger Heil (Ed.): Dreieichenhain im Wandel, 750 years of the city in the center of Europe . Dreieichenhain: Hayner Burg-Verl., 2005. 396 S .: Ill.u.graph. Darst. ISBN 3-924009-20-1 (Stadt und Landschaft Dreieich; 21).

- Rudolf Knappe: Medieval castles in Hessen. 800 castles, castle ruins and fortifications. 3. Edition. Wartberg-Verlag, Gudensberg-Gleichen 2000, ISBN 3-86134-228-6 , p. 408f.

- Hanne Kulessa (Ed.): Dreieich, a city: Buchschlag, Dreieichenhain, Götzenhain, Offenthal, Sprendlingen . Frankfurt 1989.

- Gernot Schmidt (Ed.): Dreieichenhain. Contributions to the history of the castle and town of Hayn in the Dreieich . Dreieich: Hayner Burg-Verl., 1983. 549 pp .: Ill. U. graph. Darst. ISBN 3-924009-00-7 (Stadt und Landschaft Dreieich; 1).

- Gernot Schmidt: Little guide through Dreieichenhain: a tour through the castle and town, church and museum; with a city map for pedestrians . Ed. Dreieich: Dreieichenhain, 1990. 46 pages: Ill (partly colored) u. graph. Darst. ISBN 3-928149-00-8 (Stadt und Landschaft Dreieich; 12).

- Rolf Müller (Ed.): Palaces, castles, old walls. Published by the Hessendienst der Staatskanzlei, Wiesbaden 1990, ISBN 3-89214-017-0 , pp. 81–84.

- Dagmar Söder: Offenbach district = monument topography of the Federal Republic of Germany - cultural monuments in Hesse. Braunschweig 1987, pp. 102-104., ISBN 3-528-06237-1

Web links

- Burg Hayn - Internet presence of the history and homeland association

- Website historical old town Dreieichenhain

- Dreieich Museum

- Burgfestspiele - The festival at Hayn Castle

- Jazz in der Burg - annual jazz festival since 1975

- Hayner Castle Festival with medieval market

Individual evidence

- ↑ Cf. Gernot Schmidt: Dreieichenhain . In: Kulessa (Ed.): Dreieich , p. 36.

- ↑ Cf. Gernot Schmidt: Dreieichenhain . In: Kulessa (Ed.): Dreieich , p. 36; Karl Nahrgang : A fortified hunting farm in the Ottonian period . In: City and District Offenbach a. M. Studies and Research, H. 9.1963, pp. 243-263.

- ↑ cf. Horst Wolfgang Böhme: Critical remarks on the Salian tower castle of Dreieichenhain and its predecessor buildings . In: Hessisches Jahrbuch für Landesgeschichte , vol. 55.2005, pp. 251–262, Karl Nahrgang also carefully corrected this, his own theory in his last publication - published posthumously in 1970: Karl Nahrgang: Dreieichenhain, Königshof, Burg, Stadt . In: Castles and Palaces. Vol. 1970, H. 2, pp. 51-60.

- ↑ Söder, p. 102.

- ↑ Cf. Gernot Schmidt: Dreieichenhain . In: Kulessa (Ed.): Dreieich , p. 37.

- ↑ Söder, p. 102.

- ^ Uta Löwenstein: County Hanau . In: Knights, Counts and Princes - Secular Dominions in the Hessian Area approx. 900–1806 = Handbook of Hessian History 3 = Publications of the Historical Commission for Hesse 63. Marburg 2014. ISBN 978-3-942225-17-5 , p. 210 .

- ↑ Söder, p. 103.

- ↑ In front of the altar piles of rubble pile up in FAZ of December 6, 2017, page 45