House of the Golden Scales (Frankfurt am Main)

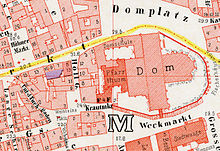

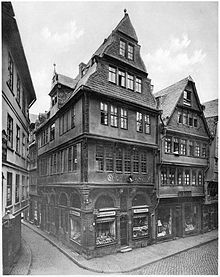

The Haus zur Goldenen Waage was essentially a medieval half-timbered house in the old town of Frankfurt am Main , which was destroyed in the air raid on March 22, 1944 . Because of its high architectural and historical value, it was one of the most famous sights in the city. It was located in front of the main portal of the cathedral as a corner house on the narrow Höllgasse and on the market , the old town street leading from the Domplatz to the Römerberg .

The richly detailed renaissance facade dates from 1619. The remains of the house, which would have allowed it to be rebuilt after the war, were removed in 1950. The arcades remained, however, as part of a private library in Götzenhain . The property was fallow for more than 20 years. In 1972/73 during the construction of the Dom / Römer underground station , the archaeological garden was created , in which excavations of the Roman settlement on the cathedral hill and the Carolingian royal palace in Frankfurt were made accessible.

In 2007 it was decided to reconstruct parts of the former old town as part of the Dom-Römer project , including the rebuilding of the Golden Scales . The new building began in 2014. The archaeological garden was partially built over, but remains accessible via the neighboring town house on the market .

In December 2017, the restored half-timbered facade, the renaissance ceiling inside and the belvedere were completed. The building, which has also been restored inside, opened in December 2019. It is accessible as part of tours of the Historical Museum . There is a café on the ground floor.

history

prehistory

The corner house on Markt and Höllgasse was already mentioned in the early Middle Ages , probably after its owner at the time, as Haus zum Kulmann and zum Colmann . The earliest mention of a year dates back to 1323. In 1405 it was combined with the Alte Hölle rear building to form one property. Around this time, the term Höllgasse was popularly used for the very narrow, densely built-up and extremely dark cross-connection between Markt and Bendergasse, even by medieval standards . There was also a house called Junge Hölle , which was located on the east line of Höllgasse, directly across from the Old Hell . Most of the houses were on this side of the street, taking into account the overhangs, basically already with the 1st floor on the property of the cathedral - much to the annoyance of the cathedral monastery: A first case is recorded in 1299 in which the goldsmith Colmann opened up about his house the Ostzeile of Höllgasse got into a dispute with the clergy.

The golden scales under Abraham van Hamel

In 1588, the corner house Goldene Waage came into the possession of Andreas Gaßmann for 3,040 guilders and the Alte Hölle for 2,000 guilders . The confectioner and spice trader Abraham van Hamel finally bought the building complex from Maria Margarethe Gaßmann in 1605 . Hamel came from Tournai in the Spanish Netherlands . In 1599, as a reformed religious refugee , he immigrated to Frankfurt via Sittard near Aachen and Wesel , where his father and brother had already settled as citizens. Despite some resistance from the guilds , he was admitted to the citizen oath on November 19, 1599.

From 1618 to 1619 he had the four-story front building of his property torn down and replaced it with a magnificent new building. His plan was accompanied by fierce opposition from the council and envious neighbors. The public display of wealth was frowned upon in Frankfurt - the client of the similarly splendidly decorated salt house had felt that too. Hamel, however, was a contentious man who usually achieved his goals, sometimes ruthlessly - either by using his fortune or by taking legal action. His complaints quickly made him an outsider among the Frankfurt citizens, who soon said, "He had to quarrel with everyone and justify that a strange councilor would have to be appointed for his quarrel alone."

The dispute over the construction of the Golden Scales has also been handed down to the present day in files in the city archives and in literature:

In February 1618, Hamel asked for permission for the first time to completely lay down his dilapidated house and replace it with a four-story new building, i.e. a ground floor with three upper floors. Although Hamel promised to strictly observe the regulations of the law, which among other things included avoiding overhangs, so that “narrowing the streets and other bad and bad conditions could not be driven on in the least”, the building was, in Hamel’s opinion "A fair amount of prosperity, ornament and the best appearance" would not have been granted. The neighbors, all of Frankfurt's long-established merchant and patrician families, objected because, in their opinion, the tall building would have deprived the narrow street of light and air and increased the risk of fire. They did not allow the immigrant to build. In the transcript it says, "In terms of justice and equity, one should not prefer a Dutchman, who was born to be an advantage, over other local elderly citizens".

Hamel, on the other hand, held that he was "very interested in gaining more space because of his trade", since land on the market was very expensive and he therefore had to build it high in order to make the best possible use of it. Back then, the market was a main shopping street, comparable in importance to today's Zeil . Hamel lost this trial, and contrary to the original plans , the Golden Scales only became a three-story house.

At the beginning of July 1618, when the ground floor and the half-timbered skeleton above were already completed, another complaint from a neighbor was directed against the building. An inspection by the lay judges revealed that the first floor was too high by one shoe - corresponding to around 28.5 cm - compared to the construction plan submitted by Hamel. The construction almost had to be abandoned because of this, but Hamel used his fortune here, as so often. Even if there was another violation of the construction plan to accelerate the construction work so that the house would be ready for the autumn fair in 1618, he paid a fine of 100 Reichstalers and was "left at that".

Nevertheless, the house was not finished for the autumn fair in 1618, because the locksmith Jacob Reynold, who made the grilles between the round arches and skylights on the ground floor, delivered so late that the house was not occupied for almost a year and could not be completed until 1619. This cost Hamel a lot of money because in the meantime he had to rent various houses for his family and his goods. When the bars were then ready, another legal dispute broke out because they did not have the samples Hamel wanted, taken from the front door of Councilor Johann Martin Hecker. Instead, Reynold, according to Hamel's opinion, “had given the Gerembs so much thought that there would inevitably result in noticeable damage from light alone, with many excessive rings that were not provided for in thought” prison custody was more than enough. ”He refused an assessment of the situation by the craft jury from the outset, as he viewed them as biased. Their verdict then fell out for the locksmith too, and Hamel let it come to another dispute before the jury. This time he won by submitting a declaration signed by all the other craftsmen involved in the construction, according to which they were "well and well, satisfied and paid without any quarrel or misunderstanding".

Even though Hamel was a confectioner by trade, he mainly pursued the spice and paint trade, which is evidenced by a city council submission that raised him to “merchant” in 1619. Through his far-reaching trade relationships in the entire Middle Rhine region, parts of northern Germany, but also in his original homeland, he soon acquired a fortune that went far beyond the wealth otherwise customary for wealthy Frankfurt merchants. When he died on January 19, 1623, he already owned the entire west line of Höllgasse and the Wolkenburg house adjoining it at Krautmarkt (address: Krautmarkt 7 ).

After the Hamel era until it was acquired by the city

Now it was up to the widow and a younger brother of Hamels to maintain business relationships, which they obviously only managed to a very limited extent under the conditions of the Thirty Years' War that had broken out . From 1631 to 1635 the city was temporarily under Swedish occupation. At that time, the horrors of war also reached Frankfurt. In the three plague years from 1634 to 1636 alone , almost 14,000 people died in the city overcrowded with refugees, which in the peace years only had about 15,000 inhabitants. An unprecedented rise in prices impoverished large parts of the population and triggered years of famine .

When the widow Hamel died on July 25, 1635, the outstanding balance alone amounted to 60,000 guilders, the real estate was relatively heavily in debt.

As a consequence, her heirs sold the Goldene Waage and Alte Hölle for 8,500 guilders on March 5, 1638 to the Frankfurt trader Wilhelm Sonnemann. In the following centuries the owners often changed. From 1655 to 1699 it was the Barckhausen family, from 1699 to 1748 the Grimmeisen merchants and from 1748 to 1862 the von der Lahr family. This was followed by the Osterrieth and Scheld families, until in 1898 the city itself acquired the building complex for 98,000 marks.

The golden scales in the 20th century

From 1899 a fundamental renovation was carried out by the master builder Franz von Hoven . He was a native of the early 19th century plaster or Verschieferung the facade remove and expose the truss. Partition walls and crates that were subsequently inserted in the interior were dismantled. Only a few years later, the east line of the very narrow Höllgasse was demolished in order to enlarge the Domplatz. In 1913, the city made the Golden Scales, which was optically much more distinctive thanks to these measures, available to the Historical Museum . This set up the house in 1928 as an example of a Frankfurt town house from the early 18th century.

On the one hand, the fact that the last major extensions came from that time spoke in favor of this decision. Furthermore, there was an exact inventory of the house at the time of Hamel's death. Such inventories were taken in Frankfurt by city officials or the court clerk at the death of every citizen with significant property. The inventory from 1623 has not been preserved, but the one from 1635 has been preserved, because when the widow Hamel died, it was taken again. Since the legacy was classically already distributed when the inventory was taken, the inventory from 1635 also reflects the state of the interior furnishings very precisely that was in place when Hamel died. On this basis, the museum was able to equip the rooms true to the original.

During the Second World War , the first air raids on Frankfurt am Main caused only minor damage until 1942, but as a precaution the Association of Old Town Friends had the entire building stock of the old town recorded in photographs and drawings from summer 1942. With the start of the Combined Bomber Offensive in 1943, Frankfurt also became a target for area attacks. The Golden Scales initially remained unscathed, although the attacks on October 4, 1943, January 29, 1944, and March 18, 1944 caused great damage in the immediate vicinity. The air raid on Wednesday, March 22nd, 1944, drowned the entire old town between the cathedral and the Römer in the firestorm and also destroyed the Golden Scales. Incendiary bombs ignited the splendid half-timbering and burned the house down to the walls of the sandstone plinth. Particularly tragic was the loss of many historically and materially irreplaceable art treasures firmly connected with the building, including the elaborately crafted ceilings in the various rooms and the tiled stove on the first floor. Most of the exhibits housed there by the Historical Museum had previously been relocated and survived the war unscathed.

With the rescued inventory, the preserved foundation walls and the remains of the ground floor, a reconstruction, similar to the salt house and perhaps in a simplified form, would have been entirely possible. However, the city decided to completely remove the rubble of the destroyed houses between the cathedral and the Römer by 1950. The arcades of the Goldene Waage were sold to a private person from Götzenhain , who used them to build a private library for his villa.

During the reconstruction of the old town, which began in 1952 and was essentially completed by 1960, modern residential and functional buildings were created with a completely new layout of the properties and traffic routes. The area between the cathedral and the Römer, including the property of the Goldene Waage , was left out and remained fallow until the early 1970s. Excavations in the 1950s brought to light numerous testimonies to the Roman, Merovingian, Carolingian and late medieval building history of the area. In 1972/73 the area was partly built over with an underground car park and access to the Römer underground station , which raised the level of the site by more than a meter, and partly added to the archaeological garden .

In September 2000 the diocese of Limburg acquired the former main customs office opposite the Goldene Waage and subsequently had it converted into the house at the cathedral . As a result of the expansion to the south, its massive structure moved up to 4.50 meters from the former Goldene Waage , while the market was around eight meters wide before the destruction.

reconstruction

At the beginning of the 21st century, the city began planning the future design of the area between the cathedral and the Römer . In 2005 - more than 60 years after the destruction of the old town - a preference emerged in the citizenry and the city council for the most accurate restoration of the historical floor plan with alleys, squares and courtyards as well as the reconstruction of individual houses of significant urban development. Lord Mayor Petra Roth suggested in a newspaper interview that four historically significant buildings, including the Golden Scale, be reconstructed.

In order to evaluate the technical possibilities of a reconstruction, the city had a documentation of the old town created in 2006 . The study found that none of the buildings could be faithfully reconstructed historically, not even the particularly well-documented Golden Scales . A creative reconstruction, "in which the street facade and the basic floor plan in particular could be copied and possibly supplemented," seemed possible. The historical city plan could only be partially reconstructed; in particular, the Goldene Waage could no longer be bought at its original location because of the house by the cathedral . In order to keep the excavations of the archaeological garden accessible, a building should be built into which larger intercepts were to be introduced. Further tests were necessary, for example whether the historical level of the streets and ground floors could be maintained. The current building regulations had to be observed with every reconstruction, especially with regard to fire protection , energy efficiency and the possibility of secured escape routes . Stairwells were to be sealed off in a fire-resistant manner and made of non-combustible materials.

On September 6, 2007, the city council decided with the votes of the CDU , Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen , FDP and Free Voters against the votes of the SPD and Die Linke the redevelopment of the Dom-Römer area. Part of the decision was the reconstruction of at least seven buildings, including the Golden Scales .

The Jourdan & Müller office received the order to reconstruct the Golden Scales . In the south, the new Goldene Waage is now connected to the town house , in the west to the Weißer Bock house (Markt 7), both of which are contemporary designs.

The building construction work began in 2014. A specialist company in Lemgo was commissioned with the reconstruction of the half-timbered structure, for which around 100 cubic meters of old oak from historical buildings are being reused. More than a dozen spolia recovered and preserved from the rubble were reused during the construction.

In December 2017, the externally completed new building, including the restored half-timbered facade, the renaissance ceiling inside and the belvedere, was presented at a press conference. In September 2018, the New Frankfurt Old Town was inaugurated with a two-day public festival. The interior work on the Golden Scales was not yet completed at this point. The café on the ground floor opened in September 2019. A branch of the history museum is to be set up on the two upper floors.

architecture

Exterior

Externally, the Goldene Waage was at first glance a typical Renaissance building in Frankfurt's old town: a high plinth made of red sandstone showed filigree, richly decorated arcades on the outside - four on the side facing Höllgasse , two on the market . The arcades were based on protruding warriors ; the keystones were carved out as lion heads. The front door, adorned with a double lintel, slid in between the two arcades on the side of the house facing the market . While the upper one was braced with the extended column shafts of the arcades, the lower one was almost straight and showed the marriage coat of arms of Abraham van Hamel and his wife Anna van Lith in its keystone (see picture).

The marriage coat of arms consisted of two rider shields placed close together. The heraldic right shield showed a vertical arrow with barbs and three lines through the shaft. The arrow ended between two ovals, which with their bends and a connecting line formed an A (braham), in the ovals themselves you could read the letters V (on) and H (amel). The heraldic left shield bore three ermine tails in the lower two thirds and the letters A (nna) V (an) L (ith) in the upper area. The crest was a watchful ram (mutton), undoubtedly an allusion to the name of the builder.

By the standards of the early 17th century, the building was a masterpiece of statics : the openwork arcades on the ground floor were unsuitable as load-bearing elements in terms of material and design. However, this was entirely intentional, as the ample space on the ground floor could be used to display the goods. As a result, the Golden Scales was in principle a house on pillars, of which one could only see the reinforced northeast corner from the outside. The remaining seven statics columns on the ground floor ran between the arcades, but were so perfectly incorporated into them that they were given more decorative significance. The located below the fighters of the column shafts corbels were designed by Steinmetz affectionately: in massive on the northwest corner you could see a squatting man between Blum festoons (see picture.) The other seven presented alternately one male and one female head (see picture) Only the stone on the outermost (in the plan view, westernmost) side of the house on the market was special in itself, as it represented the head of a ram or mutton - whether this could be seen as an allusion to the name Hamel, as was the name of the stonemason never clarified.

Well-known, however, is the name of the master mason, Wolf Burckhardt, who was involved in the construction, as well as the fitter Jacob Reynold, who was responsible for the wrought-iron grating between the arches and the skylights.

A low mezzanine floor, the bobsleigh floor, was located in the base above his office rooms . The mezzanine served as a storage room for the sales office below. It was lit by the skylights of the arcade windows.

Two cantilevered half-timbered floors rose above the ground floor with the gable side facing the market , and two more gable floors above. Compared to the first, the second floor only protruded again on the house side facing the market . The very fine design of the half-timbered structure , a pattern of St. Andrew's crosses , on the east side facing the cathedral, was roughly comparable to the Black Star that was created on the Römerberg shortly before . In contrast to the Golden Scales , this one was rebuilt after it was destroyed in the war in the early 1980s. The half-timbered upper storeys also had almost continuous rows of narrow windows on all sides. On the first floor there were eleven on the east side, six in the north, twelve on the second floor in the east and four in the north. The glazing dates from around 1750.

The corner pillar, which is statically important for the framework, was decorated throughout with magnificent carvings (see picture): from bottom to top you could see the patriarch Abraham with a mutton to the side and a golden scale. At the foot of the beam, an arm chased in metal and holding a golden weighing pan extended out of the building. The name of the house is probably derived from this. The arm was located above the front door until 1899 and originated from a time when houses, due to a lack of house numbers, required such clear pictorial identification features. The arm with weighing pan attached after the renovation was a detailed replica, the original, exposed to almost 400 years of wind and weather, found a place in the city history museum inside the house.

The north-western corner pillar of the upper floors facing the market was just as elaborately carved as its counterpart facing the Domplatz; However, this was largely lost in the shadow of the overhangs of the neighboring Weisser Bock house (house address: Markt 7 ).

After all, there was a gable roof, which is classically steep for houses of this type and is covered with slate . The gable side facing the market was curved in the typical Renaissance shapes , which were also used in the Salzhaus .

The names of the master carpenters responsible for the construction have been handed down: Friedrich Stammeler and Barthel Hilprecht, who, even if this could never be fully clarified, possibly also prepared the construction plans. The roofer was called Niclaus Gebhard.

Interior

Ground floor and basement

Two entrances led into the interior of the building: one was a door carved into the arcade on the far left or the southernmost arcade when viewed from Höllgasse ; the second door was on the market center in the north side of the building. Whoever entered the building through the first door came into a small right-angled courtyard, the rear part of which was open to the sky. There was a trap door to the basement just behind the front door. Furthermore, one could see a pump on the west wall facing straight ahead, but it was no longer working at the time when the house became the property of the city. There was also a well in the basement of the house for the water supply. Two more doors led out of the courtyard: on the north wall a heavy wooden door, on the west wall an even more powerful riveted wrought iron door with a knocker, which probably originated from Hamel’s time and led directly into the vestibule of the Old Hell building (see picture) .

A barred window above the door leading into the vestibule let in little natural light into the vestibule. On the south wall you could still see the outlines of a walled-up door to the neighboring town of Miltenberg ( street address: Höllgasse 11 ), which, like the entire west line of Höllgasse, was once owned by Hamels. Another arched passage led from here into the storeroom of the Old Hell .

The ceiling of the room was decorated with paintings from the second half of the 16th century. Overall, this part of the building was older than the Golden Scale : a walled-up door arch still had the year 1577 in the keystone, while the Golden Scale was not completed until 1619. The room was also connected to the back courtyards of the market via an iron door . Hamel still stored his goods in it, later owners used it, among other things, as a horse stable, as later built-in cribs show. Finally, the museum exhibited various ancient vehicles here. The room was a so-called basement neck when a staircase once led from it into the basement of the Old Hell . When this was merged with the golden scales and part of the basement rooms were given to the green linden tree on the market to the west , these stairs became obsolete.

The doors, which were often walled up over the centuries, the displaced cellars and the unclear ownership situation had led to plenty of legends: in the vernacular it was often said that the golden scales were haunted .

The vestibule originally served as a staircase in the Old Hell , which reveals the very old character of the building: the vestibule was once open to the courtyard, and in front of the upper rooms were arbor-like forecourts with wooden balustrades. This type of construction was often found in half-timbered houses in Frankfurt's old town even in the early 20th century. However, as part of the construction of the Golden Scales , Hamel had ceilings drawn into the vestibule and thus created more rooms above the vestibule. Since these, as can be seen in the cross-section of the house, had a much lower ceiling height than the original rooms of the Old Hell , and these were also not at the same height as the rooms of the Golden Scales , a tower with a spiral staircase was built between the two buildings. On the ground floor, the stairwell was accessible via the wooden door in the north wall of the courtyard that opened onto Höllgasse .

Via the stairwell you first got to the shop of the Goldene Waage, which was on the same level . The City History Museum occasionally used it for special exhibitions as well as for tourist sales purposes. It was also accessible through a door on the north wall of the house that opened onto the market . The room had also served Hamel as a shop for his business. On the south side, a beautifully crafted staircase led to the low mezzanine floor, known as the bob floor (see picture). Its parapet was designed in the same style as the stair railing and was interrupted by a massive column made of red sandstone with an Ionic capital , extending over the entire height of the room . The ceiling, which only extended a little above it, was a beautifully designed, painted coffered ceiling . It showed a medallion in two fields framed by stucco molding, the eastern one with a female figure, a scale and a sword, the western one another female figure, holding a pair of snakes in her hands.

On the west wall it was connected to the stairwell. From here you can get to the first floor in just a few steps. On the way there you passed the entrance to the first mezzanine above the vestibule of the Old Hell in the west . According to the inventory from 1635, this once served as a kitchen and now with the room behind it as a library for the museum.

First floor

Here you first stepped into a hallway running in a west-east direction. A door to the left or north of the observer led to the Great Hall , which took up the entire northern half of this floor (see picture). This was always brightly illuminated by the light streaming in through six windows in the north wall facing the market. In addition to countless treasures from bourgeois households, which the Stadtgeschichtliches Museum had brought together from various collections to illustrate the upscale bourgeoisie of the time around 1700, the room possessed above all two extraordinary treasures that still came from Hamel's time and also from himself:

For one thing, the entire ceiling was covered with multi-colored stucco ; the entire stuccoed area measured 7.20 by 5.40 meters. In the middle of this rectangle there were two dominant octagons that showed themes from the Old Testament with the visit of the angels to Abraham and the sacrifice of Isaac . In the four corners of the aforementioned rectangle one could see representations of the story of Tobiae in ellipses. The free space between these geometric figures was richly decorated with scrollwork, fruit, putti , birds and musical instruments. The ceiling was a masterpiece of craftsmanship in its entire system, as the plasterer had to work in comparatively cramped conditions despite the spaciousness of the room and therefore had no way of checking his work from a great distance.

The other treasure was a green-glazed tiled stove in the south-west corner of the room, which, according to a number incorporated into the tile, dates from 1621. He also showed biblical scenes in his tiles, such as the discovery of the child of Moses , Susanna in the bath and twice, probably fired according to the same hollow shape, Samson with the gate wings of the city of Gaza .

Back in the hallway, two doors on the south side lead to the rear room , which in Hamel's time probably served his daughters as a bedchamber, but was divided into two rooms around 1700 by adding a partition.

The spiral staircase of the staircase led to the second floor, again past a mezzanine floor accessible to the west above the former vestibule of the Old Hell , which was once used as a sugar chamber and was most recently set up as a laboratory for the museum's photo development.

Second floor

The second floor was basically identical in structure to the floor below; however, the rooms to the north and south of the corridor had been separated by partition walls since the time of Hamel, so that four doors led into four rooms.

Obviously at the time when the house was owned by the Barckhausen family, i.e. at the end of the 17th century, additional furnishings were added here. A stucco ceiling, albeit a comparatively simple one, had been put up in the north-eastern room. It was divided into fields and showed a pelican feeding a boy in the middle - an indication of the use of the room as a nursery. At the same time, the pelican was also the crest of the Barckhausen family's coat of arms. In addition, a large double door (see picture) to the north-western room had been built in, which was flanked by detailed Corinthian pillars .

The furnishings of the other rooms on the floor were much simpler than those of the previous floors, and there were hardly any spatial decorations from the earlier days of the house. Over the centuries, they served the various owners as a bedchamber or study. The museum had furnished them using large quantities of original furnishings, assuming their former use as a writing room, music room, kitchen and apartment of a male resident.

Back in the stairwell, on the way to the roof on the western side, one could see the third mezzanine floor above the vestibule of the Old Hell . However, in contrast to the previous mezzanine floors, the west wall was broken through and led via a staircase to the second floor, which is a little lower above the storage room of the Old Hell . In this area of the house, referred to as the workshop in the inventory from 1635 , Hamel once built boilers, pans and ovens for his original trade. A staircase led from here to the attic of the Old Hell . This was also named in the inventory as chambers higher up . In addition to information from the inventory that there was a sparse sleeping place for Hamel's apprentices, the ingredients for the workshop below were stored there. The rooms, like the two top floors of the Golden Scale, were now largely used for museum administration. The caretaker's apartment was located in the converted attic of the Old Hell .

Following the stairs, the stone steps turned into wooden ones, and the half-timbered character of the stair tower revealed itself in the walls. On the south side one could still see a wooden hatch with an elevator construction, which made it possible to transport goods delivered in the courtyard to the attic.

The belvedere

The building was literally crowned by the pointed, slate end of the stair tower, which led to an open roof garden, the so-called " Belvederchen " (see pictures) , to the west .

Such roof gardens were quite popular in the old town because, in addition to the beautiful view, they also offered fresh air, which was a rarity in the polluted alleys of the old town. Under the Catholic prince Carl Theodor von Dalberg , who among other things also prohibited the overhangs in new buildings, they gradually fell into disrepair. So could only on the one similar loft conversions in the early 20th century house for Schildknecht on Hühnermarkt 18 , the House for Holderbaum and Hirschberg in Saalgasse 30 and the as Gewürzhaus known house for white cock on Krautmarkt 5 found. The Belvedere of the Golden Scales was undoubtedly the largest and most magnificent of them.

The Belvederchen was on at right angles to the Golden scales erected behind the neighboring houses on the market running old hell and consisted of a lead-covered roof garden with dimensions of 6.40 to 4.80 meters. On the south side there was an ornamental fountain with a roofed, shell-shaped marble bowl between two winding Corinthian columns, the roof itself being decorated with colored stones. The well was fed from a cistern on the roof. A few steps above the roof garden was a wooden arbor with a base area of 8.20 by 2.70 meters. Instead of the windows, the arbor had wooden grilles that served as wind protection and could be opened like windows. Even in midsummer it stayed pleasantly cool in the arbor. The view from the Belvederchen to the cathedral tower over the roofs of the medieval old town and the cathedral tower was often painted or photographed. a. by Carl Theodor Reiffenstein .

Since a description of this view can no longer be given today, a description from the Guide to the Golden Scales published in the 1930s is quoted literally:

“In the east, in oppressive vicinity, the red-hot sandstone blocks of the cathedral tower soar sky-high. To the south the eye wanders over the Main to the house of the Teutonic Order at the far end of the Old Bridge , over Sachsenhausen to the Mühlberg covered with gardens and country houses. Behind it, you can sense the endless forests of the old 'Dreieich' forest. In the west, the Romans , the medieval town hall with the imperial hall, beckons almost within reach . The towers of St. Nikolai and St. Leonhard greet you; The Paulskirche , which was the meeting place of the German National Assembly in 1848, rises massive and heavy from the tangle of slate roofs . Finally, Greater Frankfurt stretches to the north, lying far and slowly rising. The breathing of the restlessly working city trembles up and lets you feel the graceful peace and tranquil seclusion of the roof garden even more. Every visitor feels it differently, and it is advisable to climb up and see for yourself. "

literature

- Johann Georg Battonn : Local description of the city of Frankfurt am Main - Volume III. Association for history and antiquity in Frankfurt am Main , Frankfurt am Main 1864, p. 197f. and pp. 257-259. ( Digitized version )

- Architects & Engineers Association (Ed.): Frankfurt am Main and its buildings . [Self-published], Frankfurt am Main 1886, p. 34, 62-64 ( archive.org ).

- Rudolf Jung , Julius Hülsen: The architectural monuments in Frankfurt am Main . Third volume. Private buildings. Heinrich Keller, Frankfurt am Main 1914, p. 109–122 ( digital copy [PDF]).

- Otto Rupersberg: The builder of the Golden Wage, Abraham von Hammel, and his legacy. In: Writings of the Historical Museum IV . Directorate of the Historical Museum of the City of Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main 1928, pp. 62–84.

- Heinrich Bingemer, Franz Lerner: Guide through the golden scale. Press and advertising office of the city of Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main 1935 ( series of Frankfurter attractions 3).

- Heinrich Voelcker: The old town in Frankfurt am Main within the Hohenstaufen wall. Moritz Diesterweg, Frankfurt am Main 1937, pp. 52–72.

- Hans Lohne: Frankfurt around 1850. Based on watercolors and descriptions by Carl Theodor Reiffenstein and the painterly plan by Friedrich Wilhelm Delkeskamp . Frankfurt am Main, Verlag Waldemar Kramer, 1967.

- Georg Hartmann , Fried Lübbecke (Ed.): Alt-Frankfurt. A legacy. The golden fountain, Frankfurt M 1950, Sauer and Auvermann, Glashütten 1971.

- Manfred Gerner : Half-timbered in Frankfurt am Main. Waldemar Kramer Verlag, Frankfurt 1979, pp. 32-34. ISBN 3-7829-0217-3

- Hartwig Beseler , Niels Gutschow: War fates of German architecture - losses, damage, reconstruction. Vol. 2. South. Karl Wachholtz, Neumünster 1988, p. 827; Panorama, Wiesbaden 2000. ISBN 3-926642-22-X .

Web links

- The golden scales. altfrankfurt.com

- Markt 5 Goldene Waage on the website of the Dom-Römer project

- Photo of the preserved original arcades in Götzenhain

Individual evidence

- ↑ “Goldene Waage” is presented: Old town opening in plan , Focus , December 13, 2017

- ^ A renaissance ceiling from today in FAZ of February 24, 2017, page 35

- ↑ Guided tours of the historical museum

- ↑ Press release from November 16, 2018 at par.frankfurt.de , the former website of the City of Frankfurt am Main

- ↑ a b c The architectural monuments of Frankfurt am Main . Vol. 3. Private buildings. 1914, pp. 109-122.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Guide through the Golden Wage 1935.

- ↑ a b c d The builder of the golden balance, Abraham von Hammel, and his legacy. In: Directorate of the Historical Museum of the City of Frankfurt am Main (ed.): Writings of the Historical Museum . 1928, pp. 62-84.

- ↑ The Fate of War German Architecture - Loss, Damage, Reconstruction - Volume 2, South . Karl Wachholtz Verlag, Neumünster 1988, p. 827

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Klötzer : Then Stoltze would be back on the chicken market. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . October 14, 2005, accessed January 13, 2016 .

- ^ Dietrich-Wilhelm Dreysse, Volkmar Hepp, Björn Wissenbach, Peter Bierling: Planning area Dom - Römer. Documentation old town. City Planning Office of the City of Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main 2006 ( online ; PDF; 14.8 MB)

- ↑ Verbatim minutes of the 15th plenary session of the city council on Thursday, September 6, 2007 (4:02 p.m. to 10:30 p.m.). In: PARLIS - Parliamentary Information System of the City Council of Frankfurt am Main. Retrieved January 11, 2018 .

- ↑ Matthias Alexander: Seven old town houses are to be reconstructed. (No longer available online.) In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. May 7, 2007, archived from the original on January 13, 2016 ; accessed on January 13, 2016 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Frankfurt City Hall. Retrieved May 26, 2018 .

- ^ House of Weißer Bock. Dom-Römer GmbH, accessed on May 27, 2018 .

- ↑ Construction site diary of the company Kramp & Kramp

- ↑ Rainer Schulze: Abraham and Anna are back. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. February 27, 2016, accessed January 11, 2018 .

- ↑ Goldene Waage will be a special highlight of the new Frankfurt old town

- ↑ Frankfurt am Main and its buildings 1886, p. 34, pp. 62–64.

Coordinates: 50 ° 6 ′ 38 ″ N , 8 ° 41 ′ 5 ″ E