Frankfurt Judengasse

The Judengasse was the existing 1,462 to 1,796 Jewish ghetto in Frankfurt . It was the first and one of the last of its kind in Germany before the era of emancipation in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The largest Jewish community in Germany lived here in the early modern period .

After the compulsory ghetto was lifted, Judengasse became a poor district and deteriorated. At the end of the 19th century almost all the houses were demolished. Börnestrasse , which was built in its place, remained a center of Jewish life in Frankfurt, as the main liberal synagogue and the Orthodox Börneplatz synagogue were located here .

After the destruction in the time of National Socialism and the Second World War , the street is hardly recognizable in today's streetscape in Frankfurt. The course of today's street “An der Staufenmauer” roughly corresponds to its north-western end. During the construction of an administration building, remnants of the old Judengasse were discovered in 1987 and, after a long public debate, integrated into the new building as the Museum Judengasse .

Location and development

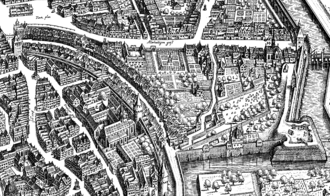

Judengasse was to the east of the Staufen wall , which separated Frankfurt's old town from the new town that was built after 1333 . Only a little more than three meters wide and about 330 meters long, it described an arc that reached roughly from the Konstablerwache to today's Börneplatz. It was enclosed by walls all around and only accessible through three gates. Due to the narrow development, Judengasse was destroyed three times by conflagrations in the 18th century alone: 1711, 1721 and 1796.

The area of the ghetto was originally planned for 15 families with a little more than 100 members. Since the Frankfurt magistrate opposed its expansion for centuries, around 3000 people lived there at the end of the 18th century. No fewer than 195 houses and rear buildings formed two double rows of buildings on either side of the alley. It was therefore considered the most densely populated area in Europe and was described, for example, by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe , Heinrich Heine and Ludwig Börne as extremely cramped and gloomy.

The Frankfurt Jews before the ghettoization

Jews were probably already among the first residents of Frankfurt. It was first mentioned in a document on January 18, 1074, when Heinrich IV granted the citizens and Jews of Frankfurt, Worms and other places certain privileges , such as exemption from customs duties. Eighty years later, however, Rabbi Elieser ben Nathan from Mainz mentioned in the manuscript Ewen ha-Eser , the “places where no Jewish society lives, as is the case in Frankfurt and elsewhere”. Grotefend emphasizes that this statement proves precisely the non-existence of a Jewish community and not, as until then wrongly assumed, its existence. In the following 90 years, however, Jews must have resettled in Frankfurt, since the so-called "Battle of the Jews" of 1241 is documented by two Jewish and one Christian sources.

Until the late Middle Ages , Frankfurt's Jews lived in what is now the old town, mainly between the Imperial Cathedral of St. Bartholomew , Fahrgasse and Main . Political life also took place in this neighborhood, one of the best areas in the city. The town hall, the mint, the guild houses of the dyers and the tanners - the Komphaus and the Loher or Lower Court - as well as a court of the Archbishop of Mainz were located here.

The Jews were allowed to settle anywhere in Frankfurt and thus enjoyed greater freedom of movement than in other cities in the Reich. Conversely, many non-Jews also lived in the Jewish quarter. Its northern houses belonged to the cathedral monastery. Although there were synodal resolutions that no Jew should live in a house belonging to the church or in the vicinity of a Christian cemetery, the Bartholomäusstift left the houses to the Jews for rent against high bail.

The "Battle of the Jews" of 1241

In May 1241, most of Frankfurt's Jews fell victim to a pogrom , which only a few escaped by accepting baptism . The few surviving sources from this period only give an incomplete picture of the events known as the “Frankfurt Jewish Battle”. The acts of violence were triggered by escalating disputes over a Judeo-Christian marriage and forced baptism .

According to the annals of the Erfurt Dominicans , only a few Christians, but 180 Jews, were killed in the course of the riots. 24 Jews, including allegedly a community leader, escaped death only by being baptized. The synagogue was looted and destroyed and the Torah scrolls torn up. A fire then spread that covered almost half of the city.

The pogrom happened although all Jews in the empire had been protected by the privileges of Emperor Frederick II since 1236 . They were in it to chamber servants declared the emperor and had to pay taxes directly to him. In addition, Frankfurt was then still under a royal mayor who presided over the court and commanded the city's military. It is not known why he or the ministerials devoted to the Hohenstaufen did not protect the Jews. The fact that the fighting lasted for more than a day and that a heavily fortified tower was stormed to which 70 Jews had fled indicates the involvement of armed forces. A Jewish lament tells of archers who attacked the rabbis and their students in the two teaching houses. This is also an indication that the "Battle of the Jews" was an organized action and not a spontaneous massacre of the urban population.

Given the uncertain source situation, those responsible can only be guessed at; It is questionable whether religious of the Dominican monastery who dedicated themselves to the fight against heresies on the papal mandate were involved. It was also suspected that the Archbishop of Kurmainz , Siegfried III, was involved. von Eppstein , who at the end of April 1241 had allied himself with the Archbishop of Cologne , Konrad von Hochstaden, against the Hohenstaufen and supported the construction of the Dominican monastery in Frankfurt. Some sources suggest that the pogrom had anti-Staufer backgrounds; However, these cannot be proven beyond doubt.

Frederick II ordered an investigation that lasted several years. King Conrad IV. On behalf of his father in 1246 granted the people of Frankfurt forgiveness for the “Battle of the Jews” in a document and waived compensation, since the citizens would have let the pogrom happen “more out of negligence than intent”. This amnesty is seen as an expression of the weak political situation of the Staufers in Frankfurt. The decision not to pursue the pogrom against their wards should possibly secure them the support of the citizens.

The destruction of the Jewish community in 1349

In the 14th century, Frankfurt was recognized as a Free Imperial City under the emperors Ludwig the Bavarian and Charles IV . The governing power was now held by the patrician- dominated council.

Around the middle of the 14th century there were again acts of violence against the Frankfurt Jews. Emperor Ludwig brought various members of the community to court for alleged crimes. The Jews panicked and a number of them fled the city. The emperor lost income that the Jews' regal , the right to rule over the Jews, had secured for him until then. He held himself harmless by moving the houses and properties of the escaped Jews in and selling them to the city of Frankfurt. According to the will of the emperor, returnees were allowed to negotiate with the Frankfurt council about the price for the return of their confiscated property. Some Jews who had fled before made use of this possibility.

In June 1349, the Roman-German King Charles IV pledged the Jewish shelf for 15,200 pounds sterling to the city of Frankfurt. Until then the royal mayor had to take care of the protection of the Jews, this task now passed to the mayor and the city council. In fact, the Frankfurt Jews went from imperial chamber servants to subjects of the council. At the same time, the Roman-German kings and emperors retained property rights over the Frankfurt Jewish community until the end of the Old Empire.

Until the emperor or one of his successors redeemed the pledge, the rulership rights of the council should extend to the Jews themselves as well as to their entire property inside and outside Frankfurt, to yards and houses, even to the cemetery and synagogue, including all associated rights of use and easements. In view of the increasing number of pogroms during the plague epidemic , which had been rampant since 1348 , Charles IV and the council had a passage inserted in the pledge that turned out to be fatal. He said that the king would not hold the city responsible if the Jews "perished or perished or were slain". The property of killed Jews should go to the city.

Two weeks after Karl left the city, on July 24, 1349, all Frankfurt Jews were slain or burned in their houses. The exact number of victims is not known, it is estimated at around 60. In the older literature, Geißler , a group of wandering religious fanatics and penitential preachers, are consistently held responsible for the deed. They had already carried out pogroms in other places because they blamed the Jews for the plague. At that time a total of around 300 Jewish communities were destroyed in Germany alone.

On the one hand, the provisions of Charles IV's document cited above speak against the authorship of the Geissler, and on the other hand, the fact that the plague did not break out in Frankfurt until autumn 1349. According to recent research, the murder attack may not have been a spontaneous riot, but a massacre that has been prepared for a long time. The murder of the Jews was in the economic interest of some patricians and guild masters, who in this way could get rid of their debts and unhindered to appropriate the Jewish property that had become free. The parish cemetery of the Bartholomäuskirche, for example, was expanded to include areas that previously housed the Jewish courts.

The re-establishment of the community

After an imperial privilege had made it possible to re-establish a community, Jews began to settle in Frankfurt again from 1360 onwards. The emperor continued to claim the taxes to be paid by the newly arrived Jews. Half of it, which he had pledged to the Archbishop of Mainz, was acquired by the city of Frankfurt in 1358. His mayor Siegfried collected the tax for the emperor , who in turn became the patron of the Jews. When the city took over the mayor's office itself in 1372, it also acquired the right to the royal half of the Jewish tax for 6,000 marks. With this, the Judenregal was once again completely in the possession of the city.

By the end of the 14th century, the community was so large again that it was able to build a new one on the site of the old, destroyed synagogue. In it, the Jews not only celebrated worship, but also took legal oaths , concluded business and received edicts from the emperor or the council. After the service, the rabbi warned against back taxes and imposed the ban on parishioners who had committed a criminal offense. When the foundations of the synagogue were uncovered during excavations, a 5.6 square meter room was discovered that was so deep that it could have reached the water table. Therefore, it was probably a mikveh .

The largest property of the Jewish community at that time was the cemetery, which had been in use since around 1270 and was first mentioned in a deed of purchase from 1300. Before the second city expansion allowed by Emperor Ludwig the Bavarian in 1333, it was still outside the city. It bordered the custodian garden of the Bartholomäusstift and was surrounded by walls early on. When Frankfurt had declared itself in favor of the candidate Günther von Schwarzburg in the controversial election of a king in 1349 and was expecting an attack from his opponent-king Karl IV, eleven oriels were installed around the old town and the Jewish cemetery. The Jewish cemetery was also brought into a state of defense during the great city war of 1388.

The Jewish population

By 1349 Frankfurt's Jews had been entered in the city's citizen lists. The second parish, which formed again after 1360, had a different legal status. Each of its members had to individually conclude a protection contract with the council, which regulated the length of stay, regular taxes to be paid and regulations to be observed. In 1366, Emperor Karl IV ordered his mayor Siegfried, who was also the highest court clerk in Frankfurt, not to allow them to have master craftsmen, to issue their own laws or to hold court themselves. All individual regulations were summarized by the council for the first time in 1424 in the Juden stedikeit and from then on read out annually in the synagogue. Already the first settlement in 1424 shows a clear tendency to exclude Jews from real estate.

Crisis and resurgence of the community in the 15th century

In the 14th century, Frankfurt did not yet have a distinct commercial upper class. Despite the fair that already existed, the trade in goods was far less pronounced in Frankfurt than in other German cities. Therefore, many Frankfurt Jews were economically active in the credit business with craftsmen, farmers and nobles mainly from the surrounding area, but also from Frankfurt. A by-product of lending money was the sale of forfeited pledges. Then there was the retail trade in horses, wine, grain, cloth, clothes and jewelry. The size of these deals was not significant. Measured against the sums of royal taxes paid by Frankfurt Jews, the economic strength of their community was far behind that of the Nuremberg , Erfurt , Mainz or Regensburg Jews until the middle of the 15th century .

Since the end of the 14th century, the Frankfurt Jews were exposed to increasing restrictions. In 1386 the council forbade them to employ Christian servants and wet nurses. He also stipulated exactly how many servants each Jewish household was allowed to keep. A general Jewish debt remission by the Roman-German King Wenceslas de facto expropriated the Jews in favor of their debtors. At the same time, the council tried to push back the growth of the Jewish community through a rigid tax policy. Between 1412 and 1416 the number of Jewish households decreased from about 27 to about four. 1422, the Council refused, citing its privileges from the recovery of an Roman-German king and later Emperor Sigismund imposed on the Jews heretics control , after which the Jews of Frankfurt with the outlawry were occupied and the city had to leave. They were only able to return in 1424 after the emperor recognized the Frankfurt legal position.

In 1416 the number of Jewish households reached a low. After that, however, it grew steadily and in the second half of the century the Frankfurt Jews generated considerable tax revenue. After the expulsion of the Jews from the cities of Trier in 1418, Vienna 1420, Cologne 1424, Augsburg 1438, Breslau 1453, Magdeburg 1493, Nuremberg 1499 and Regensburg in 1519, Frankfurt's importance as a financial center also gradually increased. Because many of the displaced elsewhere moved to the city on the Main, even though their advice only allowed the financially strongest among them to settle.

In the course of the 15th century, at the insistence of the craft guilds, which saw themselves increasingly exposed to serious competition, the money and goods trade of the Jews was subjected to restrictions. When King Maximilian assessed the Jewish communities in 17 imperial cities for a tax for his Italian campaign in 1497, Worms paid the highest sum, the Frankfurt community the second highest.

The Frankfurt Ghetto

prehistory

As early as 1431, the council began to consider again how to quit the Jews completely, because of whom conflicts with the emperor and the archbishop of Mainz had occurred again and again . In 1432 and 1438 he debated the inclusion of the Jews in a ghetto, but without immediate consequences. In 1442, Emperor Friedrich III requested at the instigation of the clergy, the evacuation of the Jews from their homes near the cathedral, because the synagogue singing allegedly disrupted the Christian worship in the nearby church. In 1446 there was a murder of the Jew zum Buchsbaum , which the council clerk noted in the mayor's book with three crosses and the comments Te deum laudamus and Crist is made . In 1452, during his stay in Frankfurt, Cardinal Nikolaus von Kues demanded that the council observe the church dress code for Jews. Jewish women had to wear a blue-striped veil, Jews had yellow rings on their coat sleeves. However, compliance with these regulations was not operated very sustainably in the future either.

Establishment of the ghetto

After another intervention by Emperor Friedrich III. In 1458, the council finally began building houses outside the old city wall and moat, into which the Jews had to move in 1462. This was the beginning of the establishment of a closed ghetto. In 1464 the city built eleven houses, a dance hall, a hospital, two inns and a community hall at its own expense. The cold bath and a synagogue, however, were built at the expense of the Jewish community.

This first ghetto synagogue, also called Altschul, stood on the east side of Judengasse and, like the old one, was not only used for religious purposes. It was the social center of the community, where profane activities were also carried out. This corresponded to the close connection between everyday life and religion in Judaism. The presence of Jews brought with it a partial independence of the community. The community leaders were elected in the synagogue, rabbinate ordinances posted, wanton bankrupts were declared unworthy and corporal punishments were carried out in front of the assembled community. The seats in the synagogue were rented out. Anyone who owed money to the community, their seat was auctioned to the highest bidder.

In 1465 the city council decided to leave the further construction of the street to the Jews at their own expense. As a result, in 1471 they left out and paved the square, built a second well and built a bathing room. The land belonged to the council, which also reserved ownership of the houses, regardless of whether they themselves or the Jews had built them. For the built-up areas he raised the land charge.

Only a century after the forced resettlement, when the houses in the Judengasse were no longer sufficient, the Jews were allowed to build on part of the trench. Thus, between 1552 and 1579, the Judengasse was built in the form that it existed until the 19th century.

Due to its economic boom, the Jewish population had grown from 260 people in 1543 to around 2,700 people in 1613. Since the Judengasse could not be expanded, new houses were created by dividing existing ones. Back houses were built on both sides of the alley so that it now had four rows of houses. Finally, the number of floors was increased and the upper floors protruded so far into the alley that the houses almost touched one another. Large multi-storey structures, so-called mid- sized houses, were placed on low houses .

Life in the Ghetto

Life in the Judengasse was extremely cramped due to the rapid increase in population, especially since the Frankfurt magistrate refused to expand the area of the ghetto for centuries.

The living conditions of the Jews were regulated down to the smallest detail by the so-called Jewish population. This ordinance of the Frankfurt Council stipulated, among other things, that Jews were not allowed to leave the ghetto at night, on Sundays, on Christian holidays or during the election and coronation of the Roman-German emperors. Beyond this isolation, Jewish residence contained a myriad of other, largely discriminatory and harassing provisions.

It regulated the right of residence, the collection of taxes and the professional activity of the Jews as well as their behavior in everyday life, including clothing. Every Jew had to wear a ring-shaped, so-called yellow spot on their clothing. Immigration to the ghetto from outside Frankfurt was strictly limited. In total, only 500 families were allowed to live in the Judengasse after the newly enacted Jewish residence in 1616, and their residents were only allowed twelve weddings per year. Even wealthy and respected residents like the banker Mayer Amschel Rothschild were not exempt from the discriminatory restrictions. Nevertheless, a flourishing Jewish life developed in the alley.

The rabbinical assembly of 1603

Frankfurt's Jewish community has been one of the most important in Germany since the 16th century. In the Judengasse there was a kind of Talmudic academy where excellent halachic rabbis taught. Also Kabbalistic works were printed in the Judengasse. The money that was collected in the Jewish communities in Germany for the poor Jews of Palestine was sent to Frankfurt and transferred from there.

The central role the Frankfurt community played in Jewish intellectual life in the early modern period was shown by the large rabbinical assembly that took place in 1603 in Judengasse. Some of the most important municipalities in Germany - u. a. those from Mainz , Fulda , Cologne and Koblenz - sent representatives to Frankfurt. The assembly dealt primarily with the jurisdiction, which the Jews were allowed to regulate autonomously and for which five courts of justice had been set up: in Frankfurt am Main , Worms , Friedberg , Fulda and Günzburg . Regulations against fraud in trade and coinage were just as much a topic of the meeting as questions of levies to the authorities, religious matters such as slaughtering and ritual regulations. However, since Emperor Rudolf II found that with its resolutions the assembly had exceeded the imperial privileges that had been granted to the Jews, the assembly triggered a high treason trial against the Jews in Germany. In the opinion of the imperial lawyers, what they called the “Frankfurt Rabbinical Conspiracy” had violated the principles of imperial law. According to this, the iurisdictio , to command and forbid the highest power, was left to the sovereigns alone. The process took 25 years. Meanwhile, the imperial protection seemed to have been canceled, which encouraged anti-Jewish riots and pogroms in Frankfurt and Worms, the two largest communities in German Jewry. The dispute was settled in 1631 when the Frankfurt community and the whole of Aschkenas took up a large sum, which the Cologne elector , the chief investigator of the trial, received as a fine.

The fat milk riot

Social tensions between the patricians , who dominated the Frankfurt magistrate, and the craft guilds led to the so-called Fettmilch Uprising in 1614 - named after its leader, the gingerbread baker Vinzenz Fettmilch - in the course of which the Judengasse was attacked and plundered and the Jews were once again temporarily expelled from Frankfurt were.

The protests of the guilds were initially directed against the financial conduct of the council and aimed at greater participation in urban politics. In addition to regulating grain prices, the guilds also demanded anti-Jewish measures, in particular a restriction on the number of Jews living in the city and a halving of the interest rate that Jews were allowed to charge on their monetary transactions. In this way, the supporters of Fettmilch found support from merchants and craftsmen who hoped that an expulsion of the Jews would also clear their debts.

At the end of 1613, the council signed a civil contract with the insurgents, which essentially meant a constitutional reform that gave the representatives of the guilds more rights and more influence. When the high debt of the city became public and it turned out at the same time that the council had misappropriated the protection money paid by the Jews, Fettmilch had the council declared deposed and occupied the city gates. There were first riots against the Jews. Now the emperor, who had been neutral until then, intervened in the conflict. He demanded the re-establishment of the council and threatened all citizens of the Reichsacht if they should not submit.

After the imperial threat became known, insurgent craftsmen and journeymen marched through the streets in protest on August 22, 1614. Their anger was directed against the weakest link in the chain of their actual or supposed opponents: the Jews. The rebels stormed the gates of the Judengasse, which were defended by the Jewish men, and after several hours of barricade fighting, penetrated the ghetto. All residents of the Judengasse, a total of 1,380 people, were rounded up in the Jewish cemetery, their houses looted and some of them destroyed. The next day they had to leave the city. They found refuge in the surrounding communities, especially in Hanau , Höchst and Offenbach .

Then the Emperor on September 28, 1614 left the imperial ban on fat milk and several of his followers impose. On November 27th, Fettmilch was arrested. He and 38 other defendants were tried. However, the court did not convict them of the riots against the Jews, but of crimes against the majesty and disregard of the imperial orders. On February 28, 1616, Fettmilch and six of his followers were executed on the Frankfurt Roßmarkt. On the same day, the 20th Adar according to the Jewish calendar, the Jews who had fled were led back to the Judengasse by imperial soldiers. A stone imperial eagle was attached to its gates as well as the inscription "Roman Imperial Majesty and the Holy Empire's Protection". As a first measure, the returning Frankfurt Jews restored the desecrated synagogue and the devastated cemetery for religious use. The anniversary of the solemn repatriation will be celebrated in the future as the Purim Vinz joyous festival after the ringleader's first name, the Purim Kaddish has a happy marching melody in memory of the pageant of the return.

The returned Jews never received the promised compensation. The Fettmilch uprising was one of the last pogroms against Jews in Germany before the Nazi era . Contemporary journalism on the events of 1612 is remarkable in that it was the first time that Christian commentators were in favor of the Jews.

The place of 1616

The new “ Jewish seat ” for Frankfurt, which was enacted by the imperial commissioners from Hesse and Kurmainz in 1616, reacted to the fat milk pogrom, but in a way that took the anti-Jewish attitudes of many Frankfurters more into account than the needs of the Jews.

So the population determined that the number of Jewish families in Frankfurt should remain limited to 500. In the 60 years before the pogrom, the number of Jewish households in Frankfurt had risen from 43 to 453, that is, by more than ten times. This provision was intended to set an upper limit for the rapid population growth in the Judengasse. The number of marriages of Jews was limited to 12 annually, while Christians only had to prove sufficient assets to the treasury to obtain a marriage license.

From an economic point of view, the Jews were largely equated with the Christian tenants : like them, they were not allowed to keep open shops, do no retail trade in the city, enter into a business association with citizens and acquire no real estate, all restrictions whose roots go back well into the Middle Ages.

One innovation was that the Jews were now expressly permitted to do wholesale trade, for example trading in pledged goods such as grain, wine and spices or long-distance trading in cloth, silk and textiles. It can be assumed that with this strengthening of the economic position of the Jews, the emperor wanted to create a counterweight against the Christian merchant families who now ruled in Frankfurt after the guilds were ousted.

Another positive determination of the new saturation for the Jews was that it no longer had to be renewed every three years. So it was equivalent to a permanent residence permit in Frankfurt. Nevertheless, the Jews were still regarded as foreigners who had a lower legal status than citizens and residents. They remained subjects of the council and, unlike Christians, could not apply for membership in the citizenship. In 1616 they were expressly forbidden to call themselves citizens. The Jews were more heavily burdened with taxes than the Christian survivors: They had to pay higher customs duties and additional taxes.

The status of 1616 was revised several times, for example B. 1660. The changes improved the situation of the Jews. In spite of this relief, saturation remained stuck in the medieval imagination into the 19th century.

The great Jewish fire of 1711

On January 14, 1711, one of the largest fire disasters that Frankfurt has ever affected occurred in Judengasse. It remained in the collective memory of the city as the Great Jewish Fire . The fire broke out around eight o'clock in the evening in the Eichel house of the chief rabbi Naphtali Cohen. With a front width of over 9.50 meters, the house opposite the synagogue was one of the largest in the whole street. The strong wind and the narrowness of the alley favored the rapid spread of the fire, as did the timber-framed houses , without adequate firewalls and with wide overhangs towards the middle of the alley.

For fear of looting, the residents kept the gates of the alley locked for a long time until the population of the Christian neighborhoods around Judengasse forcibly gained entry for fear of the fire spreading. Nevertheless, it was not possible to bring the fire under control. After 24 hours, all but one of the houses in the ghetto were burned. Because the wind had turned at the last moment, the fire did not spread to the surrounding neighborhoods.

( steel engraving by Wilhelm Lang based on a model by Jakob Fürchtegott Dielmann )

Four people lost their lives in the conflagration and numerous valuables were lost, including books, manuscripts and Torah scrolls . After the disaster, the residents of the alley were allowed to rent Christian houses in Frankfurt until their houses were rebuilt. Those who could not afford this were forced to seek refuge with Jewish communities in Offenbach , Hanau , Rödelheim and other places in the area. Jews who had lived without a place in the alley were expelled. The Jewish community of Frankfurt celebrated the anniversary of the fire, according to the Jewish calendar the 24th Tevet , henceforth as a day of penance and fast.

The first concern of the Jewish community was the rebuilding of their burned down synagogue. The new building, which had been built on the old foundations, was inaugurated at the end of September 1711. It consisted of three parts: the actual synagogue (Altschul), the three-story women's synagogue north of it, which was almost completely separated from the synagogue, and the Neuschul in the south. Only the Altschul had a few decorative elements with a Gothic vault , its own facade, two upstream half-columns and larger arched windows on the upper floor. Compared to other synagogue buildings of the Baroque period in Prague , Amsterdam or Poland, this synagogue looked medieval and backward and thus reflected the situation of the Jewish community that was forced into a ghetto.

The council issued strict building regulations for the reconstruction of the alley. The architectural drawings that have been preserved today allow a fairly good reconstruction of the old Judengasse.

The street fire of 1721

Just ten years after the great Jewish fire, another fire broke out in the alley on January 28, 1721. Within eleven hours, the entire northern part of the alley was on fire. Over 100 houses burned down. Other houses were looted and damaged by Christian residents of the city during the rescue work, so that Emperor Charles VI. warned the city council to take action against the looters and better protect the Jews. After long negotiations, the council, which owed money to the Jewish community, waived the payment of outstanding community taxes. Nevertheless, the reconstruction proceeded only slowly this time because a large part of the community was impoverished by the disasters suffered.

Again some of the injured residents had left the alley and found accommodation with Christian landlords in Frankfurt. In 1729, however, the council forced the last 45 families living outside the Judengasse to return to the ghetto.

The bombardment of 1796

(colored aquatint by Christian Georg Schütz the Younger and Regina C. Carey )

In July 1796 French revolutionary troops under General Jean-Baptiste Kléber besieged Frankfurt. Since the city was being occupied by Austrian troops, the French army deployed guns on the hills north of the city, between Eschenheimer Tor and Allerheiligentor . In order to force the Austrian commander, Count Wartensleben, to surrender, he had the city bombarded on the evening of July 12th and at noon on July 13th. An hour-long bombardment on the night of July 13-14 caused particularly severe damage. The northern part of Judengasse in particular was hit and caught fire. About a third of their houses were completely destroyed. The Austrian occupiers then had to surrender.

Despite the severe damage, the fire in the Judengasse was also good for the Jewish community, as it de facto led to the lifting of the ghetto obligation.

The end of the ghetto

(photography by Carl Friedrich Mylius )

Frankfurt was one of the last cities in Europe to maintain the ghettoization of its Jewish population. The Frankfurt Council was fundamentally anti-Jewish. In 1769, for example, he rejected a petition from the Jews to be allowed to leave the ghetto on Sunday afternoon and already considered the request to be

“ Proof of the boundless arrogance of this people, who make every effort to equate themselves with the Christian inhabitants at every opportunity. "

When the drama Nathan the Wise von Lessing appeared in 1779 , the council ordered a ban and the confiscation of the books. The Frankfurt Jews tried to improve their situation at the Kaiser and the German Reichstag in Regensburg , but this did not change significantly even after the tolerance patents of Emperor Joseph II .

Only in the aftermath of the French Revolution did the Frankfurt Jews gain freedom from the ghetto. In 1796 Frankfurt was besieged during the war between revolutionary France and the coalition of Austria , England and Prussia . Since the ghetto was set on fire, the affected residents were allowed to settle in the Christian part of the city.

In 1806, the Grand Duke of Frankfurt Carl Theodor von Dalberg, appointed by Napoleon, decreed equal rights for all denominations. In one of his first administrative acts, he revoked an old municipal decree that forbade Jews from entering the public promenades and the grounds . He made a generous donation for the Philanthropin , the community's new school. In 1807, the city of Frankfurt created a new location and again assigned the Jews to the Judengasse as their quarters. Only Dalberg's highest ordinance, the civil legal equality of the Jewish community in Frankfurt , finally abolished ghetto compulsory and special taxes in 1811. For this, however, the community had to make an advance payment of 440,000 guilders.

The Judengasse in the 19th and 20th centuries

After the end of the Grand Duchy, which was protected by Napoleon, and the restoration of Frankfurt as a Free City in 1816, the Senate again curtailed the civil rights of the Jews in the new constitution, the constitutional supplementary act , citing the majority will of the Christian citizenship. The ghetto obligation, however, was lifted. It was not until 1864 that the Free City of Frankfurt became the third German state after Hamburg (1861) and the Grand Duchy of Baden (1862) to lift all restrictions on civil rights and put Jews on an equal footing with other citizens.

Due to the cramped living conditions, most Jews left the former ghetto in the course of the 19th century and settled mainly in neighboring Ostend. The Judengasse became a poor district. Although the picturesque streetscapes attracted tourists and painters, the city wanted to get rid of the remains of the ghetto. In 1874, the houses on the west side, which were now considered uninhabitable, were demolished, and in 1884, with a few exceptions, those on the east side as well. One of the few buildings that have been preserved for the time being is the Haus zum Grünes Schild in Judengasse No. 148, the ancestral home of the Rothschilds . Mayer Amschel's widow, Gutele Rothschild , née Schnapper, did not leave it after her five sons were raised to the nobility in 1817, but lived in this small house in the ghetto where the financial dynasty was founded until her death.

As early as 1854, the Israelite community had the old synagogue from 1711 torn down and replaced by a representative new building in 1859/60. As the new main synagogue , it remained the spiritual center of the Reformed wing of the community until it was destroyed during the November pogroms of 1938 . With the redevelopment in 1885, Judengasse was renamed Börnestrasse after one of its most famous residents, Ludwig Börne , and the former Judenmarkt at its southern end was renamed Börneplatz . The Orthodox members of the Jewish community had their own synagogue built there in 1882, the Börneplatz synagogue . It was also destroyed in November 1938.

After the Nazis took power in 1933 Börnestraße in was Big Wollgraben renamed, the Börneplatz in Dominikanerplatz (after lying on its western edge Dominican monastery ). The National Socialists expelled, deported or murdered almost all Frankfurt Jews. The former Judengasse was completely destroyed in the air raids on Frankfurt during World War II.

Remains of the ghetto

After the destruction of the war, the area was completely redesigned and built over. 1952 to 1955 the openings of today's Kurt-Schumacher-Strasse and Berliner Strasse were laid out and new buildings were erected. On Börneplatz, which only got its previous name back in 1978, a wholesale flower market was built, which disappeared again at the end of the 1970s. The reconstruction of Börnestrasse was not done. As a result, the location of the former Judengasse is only rudimentarily recognizable in today's street.

The northern half of today's street An der Staufenmauer south of Konstablerwache corresponds to the northern end of Börnestrasse and the former Judengasse. The last remaining remnant of the wall itself can be seen here, on the east side of which the ghetto was located. The wide Kurt-Schumacher-Straße cuts the former course of the Judengasse at an acute angle and thus covers a large part of the former ghetto district. The main synagogue was located opposite the confluence of Allerheiligenstrasse and Kurt-Schumacher-Strasse . A plaque on house no.41 commemorates them.

The southern end of Judengasse is now under the Stadtwerke's customer center, which opened in 1990, and is accessible from the Judengasse Museum .

Museum Judengasse

At the end of the 1980s, the remains of a mikveh and foundations of houses on Judengasse were uncovered during the construction of a new administration building for the Frankfurt am Main municipal utilities . This led to a nationwide debate about how to deal appropriately with the remains of Jewish culture. Finally, some foundation walls and archaeological evidence were secured and integrated into the “Museum Judengasse”, which opened in 1992 in the basement of the administration building. The museum is a branch of the Jewish Museum Frankfurt . Part of the floor plan of the Börneplatz synagogue, which was destroyed in 1938, is reproduced in the floor design of the adjacent Neuer Börneplatz memorial .

The Jewish cemetery on Battonnstrasse

The 11,850 m² old Jewish cemetery , although mentioned for the first time in 1180, can be seen as a further testimony to the ghetto, as it served the Jewish community as a burial place until 1828. The oldest surviving graves date from 1272. This makes the Jewish cemetery in Frankfurt the second oldest in Germany after that of Worms . The most famous grave is that of Mayer Amschel Rothschild .

In terms of urban planning, the Frankfurt Judengasse was aligned precisely with the Jewish cemetery, which had been in existence for almost three centuries, and ran directly towards its cemetery gate, which was located on its south-western enclosure for centuries. The Jewish market from the 16th to 19th centuries, a place that was considerably expanded at the end of the 18th century, was located exactly at the intersection between Judengasse and cemetery. This center of Jewish life in Frankfurt am Main was renamed "Börneplatz" in 1885, in 1933 by the National Socialists in "Dominikanerplatz" and finally in 1978 again as "Börneplatz".

The Frankfurt Judengasse in literature

In his autobiography From My Life. In the middle of the 18th century , Johann Wolfgang von Goethe describes poetry and truth as an extremely crowded, gloomy city quarter:

“One of the foreboding things that oppressed the boy and also the young man was the state of the Jewish town, actually called the Judengasse, because it consists of little more than a single street, which in earlier times ran between the city wall and the moat as in a kennel might have been trapped. The narrowness, the dirt, the swarm, the accent of an unpleasant language, all together made the most unpleasant impression, if you only looked in past the gate. "

Heinrich Heine describes the situation in a similar way in 1824 in his fragment of the novel The Rabbi von Bacherach : “At that time” (meaning the time around 1500, in which the novel is set) “the houses in the Jewish quarter were still new and nice, even lower than they are now only later did the Jews multiply in Frankfurt and yet they were not allowed to expand their quarters, always building one floor over the other there, moving closer together like anchovies and thereby crippling body and soul. That part of the Jewish quarter that stopped after the great fire and that is called the Alte Gasse, those tall black houses where a grinning, damp people haggle about, is a horrible monument to the Middle Ages. "

In 1840, however, in his memorandum on Ludwig Börne , Heine expressed himself somewhat more positively about the Judengasse, as he had experienced it in the 1820s, a few years after the ghetto was lifted. He describes a winter walk with Börne, who grew up in the Judengasse:

“When we walked through the Judengasse again the same evening and resumed the conversation about its inmates, the source of Börne's spirit gushed all the more cheerfully, as that street, which was a gloomy sight during the day, was now brightly illuminated, and That evening, as my Cicerone explained to me, the children of Israel celebrated their amusing lamp festival. This was once donated to the eternal memory of the victory that the Maccabees achieved so heroically over the King of Syria. "

Börne himself drew a similar picture, oscillating between discomfort and idyll. In his book Die Juden in Frankfurt am Main from 1807 he gives his impressions after several years of absence:

“My heart pounded with anticipation when I was to see the dark dwelling again in which I was born, the cradle of my childhood. (...)

If one looks into the long, narrow corridors of the houses, the eye finds no destination and no resting point. There is a darkness that can serve as a reminder of the ten plagues of the Pharaoh, and a symbol of the intellectual culture of the Jews. On the other hand, the daughters of Abraham appear all the more charming at the gates of these dark caves, who in the most careless morning robes, half sitting, half lying, enjoy the beholder's eye, the more pure pleasure because the contemplation of their beauty leaves his heart safe and at the same time Employment of the ear is not disturbed. Standing around them are the young sons of Mercury, who, through their pleasant conversation and eternal scurrying, prove that they also have eloquence and the wings on their feet in common with their patron god. The lips are overflowing with nice jokes and funny politeness. "

See also

literature

- Paul Arnsberg : The history of the Frankfurt Jews since the French Revolution. Volume 2: Structure and activities of the Frankfurt Jews from 1789 to their extermination in the National Socialist era. Eduard Roether, Darmstadt 1983, ISBN 3-7929-0130-7 , pp. 155-183, “The following list of Jews in Frankfurt a. M. […] shows those Jews who, in most cases, have lived in Frankfurt a. M. were settled ”.

- Fritz Backhaus (Ed.): "And the daughter of Jehuda's lament and lament was great ..." The murder of the Frankfurt Jews in 1241 (= series of publications by the Jewish Museum Frankfurt am Main. Vol. 1). Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1995, ISBN 3-7995-2315-4 .

- Fritz Backhaus, Gisela Engel, Robert Liberles, Margarete Schlueter (eds.): The Frankfurter Judengasse. Jewish life in the early modern period (= series of publications by the Jewish Museum Frankfurt am Main. Vol. 9). Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-7973-0927-9 .

- Michael Best (Ed.): The Frankfurter Börneplatz. On the archeology of a political conflict (= Fischer 4418). Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-596-24418-8 .

- Amos Elon : The First Rothschild. Biography of a Frankfurt Jew (= Rororo. Taschenbücher 60889). Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Reinbek near Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-499-60889-8 .

- Frankfurt Historical Commission (ed.): Frankfurt am Main - The history of the city in nine contributions. (= Publications of the Frankfurt Historical Commission . Volume XVII ). Jan Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1991, ISBN 3-7995-4158-6 .

- Walter Gerteis: The unknown Frankfurt. New episode. Verlag Frankfurter Bücher, Frankfurt am Main 1961.

- Johannes Heil : Prehistory and Background of the Frankfurt Pogrom of 1349 , in: Hessisches Jahrbuch für Landesgeschichte 41 (1991), pp. 105–151.

- Isidor Kracauer : History of the Jews in Frankfurt a. M. (1150-1824). 2 volumes. J. Kauffmann , Frankfurt am Main 1925–1927.

- Eugen Mayer: The Frankfurt Jews. Look into the past. Waldemar Kramer, Frankfurt am Main 1966.

- Friedrich Schunder: The Reichsschultheißenamt in Frankfurt am Main until 1372 (= archive for Frankfurt's history and art. Volume 5, Vol. 2, Issue 2 = Issue 42, ISSN 0341-8324 ). Waldemar Kramer, Frankfurt 1954.

- Egon Wamers , Markus Grossbach: The Judengasse in Frankfurt am Main. Results of the archaeological investigations at Börneplatz , Thorbecke, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-7995-2325-1 .

- Thorsten Burger: Frankfurt am Main as a Jewish migration destination at the beginning of the early modern period. Legal, economic and social conditions for life in the Judengasse . Wiesbaden: Commission for the history of the Jews in Hesse 2013. ISBN 978-3-921434-33-8 .

- David Schnur: The Jews in Frankfurt am Main and in the Wetterau in the Middle Ages. Christian-Jewish relations, communities, law and economy from the beginnings to around 1400 (= writings of the Commission for the History of the Jews in Hesse, Vol. 30). Wiesbaden: Commission for the History of the Jews in Hesse 2017 . ISBN 978-3-921434-35-2 .

Web links

- Information from Museum Judengasse and website of Museum Judengasse

- The Jewish cemetery in Battonnstrasse

- The family tree in the Rothschild archive

- Short video about the history of the Judengasse and the Museum Judengasse

- Sources on the history of the Jews in Frankfurt and in the Wetterau 1273-1347

- Sources on the history of the Jews in Frankfurt and Wetterau 1348-1390

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hermann Grotefend : The Frankfurt Judenschlacht of 1241 . In: Communications from the Association for History and Antiquity in Frankfurt a. M. , 6 (1881), pp. 60-66, here p. 60.

- ↑ a b Quoted from Konrad Bund: Frankfurt am Main in the late Middle Ages 1311–1519. In: Frankfurter Historical Commission (ed.): Frankfurt am Main. The history of the city in nine articles. 1991, pp. 53-149, here p. 134.

- ^ Klaus Meier-Ude , Valentin Senger : The Jewish cemeteries in Frankfurt. Waldemar Kramer, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-7829-0298-X , pp. 10-20.

- ↑ From my life. Poetry and truth. 1st part, 4th book. In: Erich Trunz (Hrsg.): Goethe's works. Volume 9 (of the complete work): Autobiographical writings. Volume 1. Text-critical reviewed by Lieselotte Blumenthal. Commented by Erich Trunz. Hamburg edition. 9th, revised edition. Beck, Munich 1981, ISBN 3-406-08489-3 , p. 149.

- ↑ Heinrich Heine: The Rabbi von Bacherach. In: Heinrich Heine: Complete Works. Volume 2: Poetic prose, dramatic. 7th edition. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf a. a. 2006, ISBN 3-538-05347-2 , pp. 513-553, here: pp. 538 f.

- ^ Heinrich Heine: Ludwig Börne. A memorandum. In: Heinrich Heine: Complete Works. Volume 4: Writings on literature and politics. Teilbd. 2nd 3rd edition. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf a. a. 1997, ISBN 3-538-05108-9 , pp. 5-133, here: p. 23.

- ↑ Ludwig Börne, Complete Writings , ed. by Inge and Peter Rippmann, Düsseldorf 1964–1968, vol. 1, p. 7f.

Coordinates: 50 ° 6 ′ 49.2 ″ N , 8 ° 41 ′ 14 ″ E