Mayer Amschel Rothschild

Mayer Amschel Rothschild (born February 23, 1744 in Frankfurt am Main ; † September 19, 1812 there ) was a German merchant and banker . He is the founder of the Rothschild house .

life and work

Family and childhood

Rothschild's ancestors came from a branch of the Jewish Hahn family, which had lived in Frankfurt's Judengasse since 1530 . Isaak Elchanan († 1585) built the house "zum Roten Schild" in Judengasse 69 in 1567. His grandson and his descendants took this name as a family name and kept it when they moved to the rear building in 1634 (Judengasse 188) . Mayer Amschel's father, Amschel Moses Rothschild , ran a shop in Judengasse for trading small goods and changing money . The rear building had a facade width of only about 3.40 meters. Spread over three floors and an attic room, it had a floor space of around 120 square meters. The business premises, in which the merchandise were also stored, were on the ground floor. The house was temporarily inhabited by 30 people.

His son Mayer Amschel first went to a Jewish elementary school in Judengasse. From 1755 he attended the yeshiva in Fürth . Why Amschel Moses Rothschild sent his son to Fürth can no longer be understood today. If Amschel Moses Rothschild had intended to train his son to be a rabbi , visiting the yeshiva in Frankfurt would have been easier and cheaper. It is possible that the yeshiva in Fürth, unlike the one in Frankfurt, also offered classes in secular subjects such as arithmetic. After the death of his father in 1755 and his mother Schönche Lechnich in 1756, he had to break off school there again. Instead, he was sent to Hanover for a few years , where he worked in Wolf Jakob Oppenheim's company. Wolf Jakob Oppenheim belonged to the extensive Oppenheim family , one of which was one of the court factors of Elector Clemens August I of Bavaria in Bonn at the time . Court factors were independent merchants who supplied the aristocratic courts with various luxury goods and also carried out financial transactions. The fields of activity of court factors, who were often Jews, also included the procurement of antiquarian coins and other collectibles for the princely cabinets of curiosities . Mayer Amschel probably acquired the necessary knowledge of numismatics , history and art history in Wolf Jakob Oppenheim's company to become active in this business area himself.

Activity as coin and antiques dealer

Mayer Amschel returned to Frankfurt in the Judengasse around 1764 at the age of twenty. The Jews living in this ghetto were subject to strict rules. They were not allowed to leave the ghetto after dark, on Sundays or on Christian holidays. Until the French Revolution in 1789, Jews were only allowed to enter the city of Frankfurt for business purposes and then never more than two next to each other. They were not allowed to visit any taverns or coffee houses, enter any of the Frankfurt parks or take a walk on the promenades. They were also prohibited from employing Christian servants. The language in the ghetto was not Yiddish , but Jewish German, a mixture of Hebrew and the Frankfurt dialect, which many of the ghetto residents wrote in Hebrew letters from right to left.

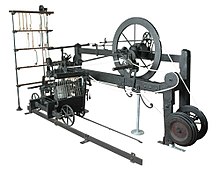

Mayer Amschel worked as a coin and exchange dealer, doing business partly independently and partly together with his brothers. During his time with Wolf Jakob Oppenheim he made the acquaintance of the coin collector General von Estorff . Thanks to this acquaintance, Mayer Amschel was able to repeatedly sell some coins to the coin cabinet of Hereditary Prince Wilhelm of Hesse in Hanau in the following years . The only invoice that proves such a deal with the Hereditary Prince comes from the year 1765 and amounts to the not very high sum of 38 guilders and 30 Kreutzers. But there must have been further deliveries, because in 1769 Mayer Amschel petitioned the Hereditary Prince to grant him the title of court factor. This request was granted and on September 21, 1769 he was able to put the plaque with the coat of arms of Hessen-Hanau and the inscription "MA Rothschild, purveyor to the court of His Highness, Hereditary Prince Wilhelm of Hesse, Count of Hanau" in front of his shop. This title was not associated with any special rights, but was useful in business with other noble customers.

On August 29, 1770, Mayer Amschel married Gutle Schnapper . The 16-year-old Gutle was the daughter of Wolf Salomon Schnapper, a court factor of the Principality of Saxony-Meiningen who also lived in Frankfurt's Judengasse . She brought a dowry of 2,400 guilders into the arranged marriage . The couple lived in the Hinterpfann house, which they had to share with the families of two of Mayer Amschel's brothers. Their share of the house was three-eighths. The couple had 20 children, five of whom survived daughters and five sons who were born between 1771 and 1792. Very little is known about the early marriage between Mayer Amschel and Gutle Schnapper. The other children probably died very early. Due to the poor hygienic conditions in the densely populated Judengasse in Frankfurt, the child mortality rate in this ghetto was 58 percent higher than in the rest of Frankfurt.

Until the birth of his youngest child, Mayer Amschel's business activity was limited to trading in coins, antiques and other rarities in which his customers might be interested. The Frankfurt sales address calendar from 1778 shows him to be the only Jewish trader who specialized in this field of business. Some of the catalogs that Mayer Amschel circulated with his customers have been preserved. These leather-bound catalogs are around ten to sixteen pages long and list old Greek, Roman and German coins as well as carved figures, precious stones and various antiques. The value of the goods offered in each catalog was 2,500 and 5,000 guilders. The coins listed were precisely dated, described and numbered according to a numismatic manual . If one of the customers showed interest, the item was sent to him for inspection and then the price was negotiated, which was usually below the guide price in the catalog. An invoice in the Bavarian State Archives shows, for example, that Duke Karl Theodor of Bavaria had a number of coins sent to him in 1789 and selected eighteen from them. The catalog price of the coins would have been 265 guilders. However, the duke paid a total of only 153 guilders and 32 Kreutzer. Mayer Amschel's annual income, which can be estimated from the book of tithe, was around 2,400 guilders in the 1770s. That corresponds to what a mayor earned annually at that time.

The family was wealthy enough to acquire the house at Grünes Schild in Judengasse 148 in two transactions from 1783 and to move into it either in 1786 or 1787. With a front width of about 4.70 meters, it was one of the largest houses in the Judengasse, compared to houses outside the Judengasse in a comparable price range - which Mayer Amschel was unable to purchase as a Jew - it was cramped and poor. The three-story house, however, had its own water pump, which was a rarity in Frankfurt's Judengasse, two cellars and a two-story rear building, which also contained the only toilet. The house, built in 1615, is considered the ancestral home of the Rothschild family. It still existed at the beginning of the Second World War, but like the other still standing houses in Judengasse, it was destroyed in the air raids on Frankfurt in 1944.

The first banking transactions

Between 1790 and 1800 there was a change in Mayer Amschel's business activity, which resulted in the Rothschilds being one of the eleven richest families in Frankfurt's Judengasse around 1800. The focus of business activity increasingly shifted from the coin and antiques trade to banking. This can also be seen in the earliest remaining balance sheet for the House of Rothschild, which dates from 1797. This shows company assets of 108,504 guilders. The assets listed include government bonds as well as personal loans and credits to a number of very different companies. On the liabilities side, there are deposits from an equally wide range of institutions and individuals, including influential non-Jewish companies and families. Mayer Amschel's creditors included the Frankfurt branch of the Brentano family , the bankers Bethmann and the Frankfurt private banker and art collector Johann Friedrich Städel . The balance sheet shows that Mayer Amschel's business partners were not only based near the city of Frankfurt, but that his business connections extended from Amsterdam, Hamburg and Bremen to Leipzig, Berlin, Vienna, London and Paris.

The increasing prosperity of the House of Rothschild under the direction of Mayer Amschel Rothschild is often reflected in his business activities for Landgrave Wilhelm IX. associated with Hessen-Kassel . The analyzes of the historian Niall Ferguson show, however, that Mayer Amschel only succeeded very slowly in establishing business relationships with the landgrave's court and that this business relationship had little influence on the Rothschilds' wealth development until 1800. William IX. was one of the richest princes in the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation . Landgrave Friedrich II. Von Hessen-Kassel , the father of Wilhelm IX., Laid the basis of this fortune with the sale of Hessian soldiers for the fight of the British crown against the North Americans striving for independence. Wilhelm IX, too. sold Hessian soldiers to the highest bidder. Payment was made in the form of interest-free bills of exchange that were only due for payment later. William IX. regularly sold these bills of exchange before they were due because the discount he had to pay the bill buyer was less than the interest he received when he invested the money. Mayer Amschel tried to participate in this discount business as early as the 1780s , but received only very small tranches up until the 1790s. In order to gain a foothold in this business, Mayer Amschel often stayed in Kassel, where he was able to renew his contacts with Carl Friedrich Buderus , whom he already knew from the time when Wilhelm IX. still lived in Hanau. Carl Friedrich Buderus was meanwhile war paymaster at the landgrave's court and as early as 1794 there was apparently a cooperation between Carl Friedrich Buderus and the Rothschild family. Buderus campaigned for Mayer Amschel to be allowed to bid on the discount loans, but was not always successful. The first major transaction that Mayer Amschel carried out for the landgrave's court took place in 1798 when Mayer Amschel, on the advice of Carl Buderus, issued Frankfurt city bonds to Wilhelm IX on more favorable terms. sold when the two non-Jewish banks Rüppel & Harnier and Preye & Jordan offered this to the court.

Electoral Oberhof agent

The volume of financial dealings with the Landgrave increased after Rothschild participated in the sale of a loan to the Landgrave in 1800. In 1803 Mayer Amschel was appointed Oberhof agent of Wilhelm, who had meanwhile been promoted to elector . Similar to the title Hofaktor, the title Oberhofagent was only an honorary title that was not associated with any rights. The award of the title, however, expresses the increasing business connection between Mayer Amschel and the electoral court. In 1804 Rothschild was able to issue and sell a government bond on his own for the first time . It was a loan from the Danish state that Rothschild was able to convey to Wilhelm in full.

In 1806 Kassel was occupied by French troops and Elector Wilhelm I had to go into exile. Carl Friedrich Buderus managed to save a fortune of 27 million guilders and thus a considerable part of the elector's fortune from French access. When managing the assets, Buderus mainly relied on the services of Mayer Amschel. Mayer Amschel, for example, collected the interest from various borrowers for the elector and reinvested it for the elector. He also bought up a large part of the electoral coin collection that the French had sold on the open market, made various money transfers for the elector and lent 160,000 guilders to the son and heir of elector Wilhelm I, who lived in Berlin. He also took care of the finances of the elector's mistress, Countess Karoline von Schlotheim .

The activities for the Elector were not without risk for the House of Rothschild, as the French authorities made numerous efforts to confiscate the Elector's property. Mayer Amschel's offices in Frankfurt were searched by the French police in 1808 and Carl Friedrich Buderus was briefly arrested in September 1808. The French special commissioner Savagner interrogated not only Mayer Amschel, but also his sons present in Frankfurt, as well as his wife and daughters-in-law. The correspondence between the Rothschilds and the Elector's officials was now written in a relatively simple code, in which Elector Wilhelm I was named as "Herr von Goldstein", "Johannes Adler" or "the Principale". However, the letters of the electoral officials no longer went to Mayer Amschel, but to Juda Sichel, whose son Bernhard had married Mayer Amschel's daughter Isabell Rothschild in 1802. Presumably, the business books were also produced in two versions during this period: One that the French authorities were able to inspect without being able to understand the transactions for the Elector and a second version that correctly and completely depicted the business of the Rothschilds. It was not until 1810, when the Grand Duchy of Frankfurt was founded under the direct rule of Prince-Primate Karl Theodor von Dalberg , that the stalking stopped.

The UK branch

Rothschild started operations in the UK

At the same time as expanding the banking business, Mayer Amschel had also expanded the Rothschild import business. Connections to companies in Great Britain are already documented by the balance sheet from 1797. Mayer Amschel's third son, Nathan Mayer Rothschild, probably worked in Great Britain from 1798, and business relationships with Great Britain expanded further from 1800. Not much has been preserved of the correspondence between father and son. The letters that have survived show that Nathan Mayer initially did not act independently, but acted according to his father's instructions. Nathan was primarily supposed to buy British textiles in Great Britain and export them to the European continent and for this reason he settled in Manchester. The goods he exported to continental Europe, however, also included other goods such as coffee or the dye indigo .

Nathan Mayer took advantage of the fact that the weavers sold their goods to traders who usually only paid for the goods after two, three or six months. Weber, who urgently needed money, were prepared to give a dealer who paid his bill immediately a significant discount. This discount was significantly higher than the amount of interest that Nathan Mayer had to pay in London for the funds raised. The transport of the textiles to his continental European customers usually took two months. Customers had to pay three months after receiving the goods. As a rule, Rothschild therefore had to secure bridging financing for the goods purchased for five months.

The business with British textiles was seasonal and cyclical and the turnover of the British branch of the Rothschild house fluctuated strongly. The war between Great Britain and France also made it increasingly difficult to export British goods. On November 21, 1806, Napoleon imposed the so-called continental lock . This economic blockade of the British Isles remained in force until 1814 and was intended to bring Great Britain to its knees by means of the economic war. The export business was then continued illegally and the goods were shipped using false papers and ships flying under different flags. Since the transport was illegal, it was no longer possible to insure the shipments. The risk for the House of Rothschild to suffer substantial loss during such a transport had increased significantly. In September 1809, a large shipload was confiscated in Riga and was only released after substantial bribes had been paid. The same thing happened with a shipload that arrived in Koenigsberg. In October 1810, the authorities in Frankfurt confiscated Mayer Amschel's contraband goods amounting to 60,000 guilders. The confiscated goods were burned and Mayer Amschel had to pay an additional fine of 20,000 francs (around 40,000 guilders).

The financial transactions for Elector Wilhelm I.

However, the presence of Nathan Mayer Rothschild in Great Britain enabled Mayer Amschel to significantly expand the financial transactions with Elector Wilhelm I. Most of the elector's fortune consisted of British government bonds. In addition, the Prince of Wales and his brothers owed the Elector about £ 200,000 and, as an ally of the British, the Elector was entitled to £ 110,150 for the years 1807 to 1810 alone. The annual interest on these papers as well as any debt repayments on the part of the British royal family were paid in London and, due to the war and the continental blockade, could only be transmitted to the elector with difficulty. Nathan Mayer had personally approached the Elector's British agent as early as 1807 to offer his financial services for the investment of these funds. However, at the express instruction of the elector, this offer was refused. Only two years later, in 1809, thanks to his connection to Carl Friedrich Buderus, his father Mayer Amschel was commissioned to acquire British government papers (so-called consoles) for the elector. By 1813 the House of Rothschild had carried out such transactions for the Elector nine times. The total value of the purchases totaled £ 664,850. These purchases were made through Nathan Mayer, who lived in London from 1808. Mayer Amschel charged the Elector 1/8 percent commission for the transactions carried out. The price of the securities and the exchange rate between the guilder and the pound were fixed. As the price of government bonds fell below the price agreed with the elector due to the British failures in the war against France, the House of Rothschild earned an average of two percent on the first three transactions, although Mayer Amschel was generally risk-averse and had the orders carried out quickly. The agreement with the elector also stipulated that the securities should first be posted to the Rothschild house or one of its agents. Only when the elector had transferred the equivalent value of the papers to a Rothschild account were the papers officially transferred to him.

This agreement proved useful for the House of Rothschild when Elector Wilhelm I stopped buying in the summer of 1811 because of the constant decline in the price of government bonds. At that time, the Rothschilds had acquired British government bonds for more than £ 100,000, which the Elector did not pay until May 1812. Up to that point, these papers were posted to Nathan Mayer Rothschild. The size of the transactions carried out for the Elector, as well as the apparent capital resources that Nathan Mayer Rothschild had at their disposal thanks to this accounting technique, ensured that the House of Rothschild was one of the major financial institutions from the very beginning of its financial activities in London.

Financial services for other European princes

So Rothschild also became court factor for the Order of St. John and the Thurn and Taxis family . At the same time, Rothschild succeeded in establishing a close relationship with Karl Theodor von Dalberg . Dalberg had since 1806 Primate of the of Napoleon Bonaparte used Confederation of the Rhine and the ruler of the formerly free imperial city of Frankfurt. In 1810 he was promoted to Grand Duke of Frankfurt . Rothschild helped him to finance his lavish lifestyle, among other things for the trip to Paris in 1810 for the wedding of Napoleon to Marie Louise . In return, Rothschild’s youngest son Jakob received permission to settle in Paris. The House of Rothschild was thus present in the capitals of both warring nations.

The increasing size, complexity and internationality of his business prompted Mayer Amschel Rothschild to put his company on a broader basis in 1810. In a new partnership agreement, he accepted his sons into the company as full business partners. The father was still at the head of the company, but the burden of everyday work was now on the shoulders of the sons. As an outwardly visible sign of the innovations, the company was henceforth called " Mayer Amschel Rothschild and Sons ".

Jewish emancipation

Mayer Amschel was now able to concentrate more on another issue, the emancipation of Frankfurt's Jews. In July 1796 French revolutionary troops under General Jean-Baptiste Kléber shot at Frankfurt. About a third of the houses in Judengasse were destroyed. The city council then de facto abolished the status , an ordinance which, among other things, prohibited Jews from owning property outside of Judengasse and forced them to take up their apartments there. In 1795 Rothschild relocated his business premises to Schnurgasse and his warehouse to Trierischer Hof outside the ghetto. In 1809 he bought a building site in the northern, burned down part of Judengasse. On this property ( Fahrgasse 146) at the corner of Fahrgasse and Judengasse, his son had the classicist office building of the MA Rothschild & Sons banking house built in 1813 .

Repeated written interventions with the Grand Duke of Frankfurt, Karl Theodor von Dalberg, finally led to the promulgation of an emancipation edict , the highest ordinance, on February 7, 1811 , concerning the civil equality of the Jewish community in Frankfurt . This meant that the Frankfurt Jews were legally equal to the rest of the citizens. But before the edict could become legally binding, the Jewish community had to pay a transfer fee of 440,000 guilders to the city of Frankfurt, which Rothschild helped finance.

legacy

Shortly after he was accepted into the electoral college of the Grand Duchy , Mayer Amschel Rothschild died on September 16, 1812. He was buried in the Old Jewish Cemetery in Frankfurt am Main in today's Battonnstrasse. His tombstone escaped destruction by the National Socialists. It was rediscovered in 1968 and placed in the honor grove. The epitaph can be accessed via an online database. The corresponding reference can be found below under the web links.

In recognition of his achievements, the Austrian Emperor posthumously elevated him to the nobility in 1817. No contemporary images of Mayer Amschel Rothschild have survived, but there are numerous anecdotes and literary testimonies.

In his will, Mayer Amschel Rothschild decreed to keep the family business as a whole. He laid down strict regulations for its management:

- All key positions are to be filled by family members.

- Only male family members are allowed to participate in business.

- The eldest son of the eldest son should be the head of the family, unless the majority of the family decides otherwise.

- There should be no legal inventory and no publication of the assets.

In the decades that followed, the descendants of Mayer Amschel Rothschild, now ennobled, rose to become Europe's leading bankers. They financed states, companies, railways and the construction of the Suez Canal . It was only with the advent of large-scale industry and stock banks in the second half of the 19th century that the Rothschild banking empire gradually lost its importance.

progeny

Mayer Amschel Rothschild had the following children with Gutle Schnapper (1753–1849), the daughter of Wolf Salomon Schnapper, whom he married on August 29, 1770:

- Schönche Jeannette Rothschild (August 20, 1771-1859), married to Benedikt Moses Worms (1772-1824)

- Amschel "Anselm" Mayer (June 12, 1773 - December 6, 1855)

- Salomon Meyer (September 9, 1774 - July 28, 1855), founder of the Rothschild Bank in Austria

- Nathan Mayer (September 16, 1777 - July 28, 1836), founder of the Rothschild Bank in England

- Isabella Rothschild (July 2, 1781--1861)

- Babette Rothschild (August 29, 1784 - March 16, 1869)

- Calmann "Carl" Mayer (April 24, 1788 - March 10, 1855), founder of the CM de Rothschild e figli branch in Naples

- Julie Rothschild (May 1, 1790 - June 19, 1815)

- Henriette ("Jette") (1791–1866) married to Abraham Montefiore (1788–1824)

- Jacob "James" Mayer (1792–1868), founder of the Rothschild Bank in France

literature

- Constantin von Wurzbach : Rothschild, Maier Anselm . In: Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich . 27th part. Kaiserlich-Königliche Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, Vienna 1874, pp. 132–135 ( digitized version ).

- Christian Wilhelm Berghoeffer: Meyer Amschel Rothschild the founder of the Rothschild banking house. Englert & Schlosser, Frankfurt am Main 1924.

- Egon Caesar Conte Corti , Beatrix Lunn: Rise of the House of Rothschild. 1928 (Reprinted by Kessinger Publishing 2003, ISBN 0-7661-4435-6 Google books ).

- Frederic Morton : The Rothschilds. A portrait of the dynasty. From the American by Hans Lamm and Paul Stein. Updated by Michael Freund. Deuticke, Vienna 1992, ISBN 3-216-07896-5 .

- Georg Heuberger (ed.): The Rothschilds. A European family. Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1995, ISBN 3-7995-1201-2 .

- Georg Heuberger (ed.): The Rothschilds. Contributions to the history of a European family. Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1995, ISBN 3-7995-1202-0 .

- Amos Elon : The First Rothschild. Biography of a Frankfurt Jew. Reinbek 1999, ISBN 3-499-60889-8 .

- Niall Ferguson: The History of the Rothschilds. Prophets of Money , 2 volumes. DVA, Munich, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-421-05354-5 .

- Pohl, Manfred: Rothschild, Meyer Amschel. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 22, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-428-11203-2 , pp. 131-133 ( digitized version ).

- Bernhard Schmidt: Article Rothschild. In: France Lexicon. 2nd Edition. Eds. BS, Jürgen Doll, Walther Fekl, Siegfried Loewe, Fritz Taubert. Schmidt, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-503-06184-3 .

- Herbert H. Kaplan: Nathan Mayer Rothschild and the Creation of a Dynasty. Stanford University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-8047-5165-X ( Google books ).

- Fritz Backhaus : Mayer Amschel Rothschild. A biographical portrait . Herder Verlag, Freiburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-451-06232-2 .

Web links

- Meir Rothschild ben Anschel Rothschild ( grave inscription in the epigraphic database epidat of the Steinheim Institute ; German and Hebrew)

- Rothschild, Mayer Amschel. Hessian biography. (As of February 23, 2020). In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

- Rothschild, Mayer Amschel in the Frankfurt dictionary of persons

Single receipts

- ↑ Elon, pp. 44f.

- ↑ Elon, p. 47.

- ↑ Elon, p. 57.

- ↑ Ferguson (2002), p. 62.

- ↑ Ellon, pp. 21 and 24.

- ↑ Elon, pp. 40f.

- ^ Ferguson, p. 62.

- ^ Edith Dörken: Famous Frankfurter Frauen , Verlag Otto Lembeck, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-87476-557-2 , p. 46.

- ^ Edith Dörken: Famous Frankfurter Frauen , Verlag Otto Lembeck, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-87476-557-2 , pp. 46 and 47.

- ^ Edith Dörken: Famous Frankfurter Frauen , Verlag Otto Lembeck, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-87476-557-2 , p. 47.

- ↑ Elon, p. 76.

- ↑ a b Ferguson (2002), p. 63.

- ↑ Elon, p. 76f.

- ↑ In the literature, different dates are given for both the purchase and the move into the house. After Amos Elon, Mayer Amschel acquired the house in 1784 and moved there in 1786 (pp. 86 and 87); According to Niall Ferguson, Mayer Amschel paid two purchase amounts, the first of which in 1783 and did not move into the house until 1787 (Ferguson 2002, p. 64).

- ↑ Elon, p. 37.

- ↑ Ferguson (2002), p. 64; Edith Dörken: Famous Frankfurter Frauen , Verlag Otto Lembeck, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-87476-557-2 , p. 47.

- ↑ Ferguson (2002), p. 65.

- ^ Ferguson (2002), pp. 82-105.

- ↑ a b Ferguson (2002), p. 84.

- ↑ Elon, p. 99.

- ^ Lothar Buderus von Carlshausen: The life of an Kurhessischen official in difficult times. In: Hessenland. Monthly for regional and folklore, art and literature of Hesse. 42nd year 1931.

- ^ Ferguson (2002), p. 89.

- ↑ a b Ferguson (2002), p. 91.

- ↑ Ferguson (2002), pp. 92f.

- ↑ Ferguson, p. 69.

- ↑ Ferguson (2002), pp. 73f.

- ↑ Ferguson (2002), p. 78.

- ↑ Ferguson (2002), p. 80.

- ^ Ferguson (2002), p. 90.

- ↑ Elon, p. 66.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Rothschild, Mayer Amschel |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German-Jewish banker and founder of the Rothschild family |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 23, 1744 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Frankfurt am Main |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 19, 1812 |

| Place of death | Frankfurt am Main |