Frankfurt-Bahnhofsviertel

|

Bahnhofsviertel 3rd district of Frankfurt am Main |

|

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 50 ° 6 '25 " N , 8 ° 39' 38" E |

| surface | 0.542 km² |

| Residents | 3552 (Dec. 31, 2019) |

| Population density | 6554 inhabitants / km² |

| Post Code | 60329 |

| prefix | 069 |

| Website | www.frankfurt.de |

| structure | |

| District | 1 - downtown I. |

| Townships |

|

| Transport links | |

| Train | S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 |

| Tram and subway | U4 U5 11 12 16 17 18 20 21 |

| bus | 33 37 46 64 n8 n83 |

| Source: Statistics currently 03/2020. Residents with main residence in Frankfurt am Main. Retrieved April 8, 2020 . | |

The Bahnhofsviertel is a district of Frankfurt am Main . It was essentially created in the German Empire until shortly after the outbreak of the First World War on the site of the former Frankfurt West Train Stations . It is located in front of the name-giving Frankfurt Central Station to the east. At 52 percent, the Bahnhofsviertel has the highest percentage of foreigners of all Frankfurt districts.

General

Area and population

At just under 0.5 square kilometers, the Bahnhofsviertel is the second smallest district of Frankfurt am Main after the old town . The longest border line is barely a kilometer long. The quarter is almost trapezoidal in shape between Mainzer Landstrasse in the north, the Anlagenring in the east, the Main in the south and the Frankfurter Alleenring in the west.

Neighboring districts are Gutleutviertel and Gallus with the main train station in the west, Westend-Süd in the north, Frankfurt city center in the east and Sachsenhausen-Nord in the south on the opposite side of the Main . The district is centrally located in Frankfurt's inner city district .

Contrary to popular belief, it is not the Baseler Strasse leading south from the forecourt of the main station that gives it its name, but the Wiesenhüttenstrasse running south-east from there that represents the exact western boundary. This means that the houses on the east side of the Wiesenhüttenplatz still belong to the station district, those on the west side but already to the Gutleutviertel. The main train station building itself is not located on the area of the Bahnhofsviertel, but on that of Gallus.

Last year the population was 3,552. In terms of its population structure, the Bahnhofsviertel is a multicultural district. As a percentage of the population, he owns most of the foreigners in the city, 65.8 percent have a migration background. At the same time, however, it is also the district in which the number of children per woman is the lowest in Frankfurt at 0.86 and is just a little more than half the national average. The population density is quite low with 7,143 inhabitants per square kilometer, which is not due to a low density of buildings, but to the high proportion of offices and business premises.

economy

In addition to the jobs in the office space, the economic focus of the district is primarily the gastronomy and retail trade, including a large number of foreign restaurants, snack bars and grocery stores due to the population structure. They are heavily dependent on the transitory role of the Bahnhofsviertel towards the city center and the general proximity to the main train station, which is an important crossroads not only for commuters in the Rhine-Main area, but also for travelers throughout Germany.

Contrary to popular belief, the red light industry only occupies a small part of the Bahnhofsviertel, it is mainly concentrated along Taunusstrasse and in parts of its cross streets, especially the northern Elbestrasse and Moselstrasse, where there are several whorehouses. However, this has a tradition here: As early as 1921, the Reichsbahndirektion Frankfurt / Main warned foreign personnel who had a break in the main train station not to visit "ill-reputed inns" here. The prostitute self-help organization Doña Carmen has its headquarters in the district and is committed to the political and social rights of prostitutes.

traffic

Due to its central location, the station district is very well connected to the transport network. The main station, which itself no longer belongs to the district but to the neighboring Gallus, offers a connection to regional and long-distance transport. The trams from lines 11 and 12 pass through the district on Münchener Straße . The Willy-Brandt-Platz underground station ( lines U1 – U5 ) and the Taunusanlage S-Bahn station ( lines S1 – S6, S8, S9 ) open up the east and north-east of the district.

The famous Kaiserstraße has lost its importance in road traffic , due to the closure of the western end ( Kaisersack ) it is no longer possible to enter from the direction of Alleenring / Hauptbahnhof. Instead, the main traffic artery today is Gutleutstrasse , which ends in the theater tunnel and provides a connection to the old town. The streets, arranged like a chessboard, allow easy orientation.

history

The area between the Frankfurt city wall and the Galgenfeld was hardly built up in the early 19th century. In the area there were only manors, on the Main there were a few country houses of the urban upper class that went back to the 18th century. The proximity to the urban gallows and the unprotected location outside the city walls prevented any development for a long time.

When the city walls and gallows were torn down with industrialization , the first villas with large gardens were built. The technical progress was particularly noticeable here. When the Taunus Railway to the then Nassau town of Höchst am Main was put into operation in 1839, the town's first train station was built on the Anlagenring.

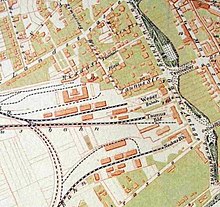

The track apron of the Taunusbahnhof ran through the middle of what is now the station district. The stations of the Main-Neckar-Bahn and the Main-Weser-Bahn were added later. These facilities, also known as Westbahnhöfe as a whole, took up roughly the area between today's Taunusstrasse in the north and Münchener Strasse in the south.

In 1888 they were replaced by the new Frankfurt Central Station , which was about 500 meters further west. This also made the track systems superfluous, and in 1889 the parceling of the area could begin. Accordingly, at the time the applicable urban planning ideas was taking into account the existing old streets Mainzer Landstrasse and Gutleutstraße an almost-symmetrical grid wide boulevards developed (Nidda, Taunus, Kaiser - Munich and Wilhelm-Leuschner-Straße), which, by narrower branch roads (Weser Mainlust-, Elbe-, Moselle-, Windmühlstraße) are regularly connected with each other.

In order to make maximum use of the only small building site, more elaborate streets were largely avoided in favor of Sternplatz, the only exception being the rectangular Taunusplatz southeast of the corner of Weser and Niddastrasse, which is now completely overbuilt. However, it had been developed from an initial approach on Taunusstrasse north of the old western train stations before the district was built. In 1891, when there was hardly any residential development, the station district became the exhibition site for the International Electrotechnical Exhibition , which Oskar von Miller directed.

The development proceeded according to plan in the style of the closed block edge , structurally mainly in the north from the area around Mainzer Landstrasse to the south and in the south from the area around Gutleutstrasse to the north, i.e. from two sides towards each other, as the former track field in the middle had only been cleared last. Accordingly, the architecture is also distributed in the design language of the various forms of historicism, and Kaiserstraße represents the most recent buildings in the district on average. With the outbreak of the First World War , which brought all building activity to a standstill, the quarter was almost completely built on. In the interwar period, apart from the new Reichsbank building on the Taunusanlage, which is still preserved today, no new buildings worth mentioning were built.

During the Allied air raids in World War II , the district was not hit as hard as the city center, but many buildings, especially in the north, were destroyed. An active nightlife developed during the time of the occupation by the American armed forces . For the post-war period, however, a disdain for the architecture of historicism was typical, which is why countless buildings, some of which are significant from today's perspective, had to give way to sober functional buildings, especially in the 1960s and 1970s, before the first monument protection laws came into force. In the south, immeasurable large buildings like the InterContinental Frankfurt , like in the Westend, forever destroyed the image of loose villa development with spacious gardens.

The station district contributed significantly to the fact that Frankfurt became one of the three centers of the fur trade worldwide, alongside London and New York, in the post-war period . The fur processing companies and trading houses were located at the fur trading center Niddastraße and extended all the way to Kaiserstraße.

Buildings over which these waves of demolition passed were neglected, at least in terms of maintenance, which contributed to the fact that the station district was considered a social hotspot , especially in the 1980s and 1990s, characterized by the drug scene, crime and sprawling red-light district. It was only with the extensive protection of the upper-class buildings in the style of the Wilhelminian era that a wave of renovations that has continued to this day and the associated structural change began. Since then, new buildings have also received the predominantly Wilhelminian-style environment instead of contrasting it as it has been up to now.

The quality of the renovations, however, still fluctuates considerably and ranges from simple, in some cases poorly listed, repainting of crumbling facades to roof extensions to the most complex, complete reconstructions of war-damaged and then simplified houses, as can be seen at the corner building at Kaiserstraße 48 / Weserstraße 21. With the appreciation of the architecture of the empire that has risen considerably in recent years, gentrification tendencies can now also be registered, as in other old quarters of the city; these gentrification tendencies continue in new building projects like the twenty7even.

The notorious drug scene could at times be curbed by the establishment of pressure rooms and other social reception facilities, which is why drug addicts who were drug addicts had largely disappeared from the streetscape in the course of the 2000s. In 2015 the station district "overturned" according to the police. In the course of the corona pandemic, the conditions continued to deteriorate and consumption on the street is not uncommon. Dealer groups from North Africa, Albania, Jamaica and East Africa have divided the drug market among themselves.

Topography and sights

The wide east-west streets of the Bahnhofsviertel are developed as boulevards and convey big city charm. Numerous Wilhelminian-style buildings survived the Second World War and the waves of demolition in the first post-war decades; they are supplemented by simpler residential buildings from the 50s and 60s and several high-rise buildings. The southern third to the Main was historically only loosely built up with upper class villas and is therefore more modern than the rest of the district.

The best-known skyscrapers are the Silberturm on Jürgen-Ponto-Platz (named after the murdered CEO of Dresdner Bank , Jürgen Ponto ) and the Gallileo on the corner of Kaiserstraße and Gallusanlage, both of which belonged to the corporate headquarters of Dresdner Bank, as well as the Skyper on Taunusstraße and the union building on Wilhelm-Leuschner-Strasse . The latter was built in 1931, the architect was Max Taut , and was the first large skyscraper in the city. The most famous of the many hotels in the Bahnhofsviertel is the InterContinental Frankfurt , also on Wilhelm-Leuschner-Straße.

In the small district there are no large, central parks as in the other Frankfurt districts, but in the south of the district on the banks of the Main is Nice , one of Frankfurt's most popular green spaces. In 1860 a silted up tributary of the Main, the Kleine Main , was filled in and the offshore island Mainlust was connected to the bank. The city gardener Sebastian Rinz laid out a green area with Mediterranean vegetation on the site, which Frankfurt locals soon called Nice . The Frankfurt families Guaita and Loën had owned large landscaped gardens in the climatically favored area on the river west of the old city walls since the 17th century .

Among the special features of the district is u. a. to count the Weißfrauenkirche in Gutleutstrasse, which was built in the early 1950s, but on which baroque grave slabs can be found. They come from the medieval church of the same name in the city center, which was sacrificed after war destruction in favor of the replacement building now in the station district, on the occasion of which the old grave slabs were transferred to the station district.

But not only the Christian religion is represented, in addition to an Islamic cultural center with a mosque on Münchener Strasse, there is also a Masonic lodge behind the house at Kaiserstrasse 37, which was built around the turn of the century based on plans by the important architect Franz von Hoven . Among other things, he was responsible for the historicist new building of the Frankfurt City Hall , the new Senckenberg Museum and the extension of the Städel . In contrast to these, the lodge is almost completely preserved in its splendid imperial furnishings.

The first museum in the Bahnhofsviertel and at the same time also unique in Germany is the Hammermuseum Frankfurt on Münchener Straße, founded in 2005 .

literature

- Thorsten Benkel (ed.): The Frankfurt station district. Deviance in public space. Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften 2010, ISBN 978-3-531-16995-8 .

- Jürgen Lentes, Jürgen Roth: "In the station district". Expeditions to a legendary district. Verlag B3, Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISBN 978-3-938783-71-9 .

- Christoph Palmert, Suzan Douma, Matthias Meitzler, Johannes Wahl: Deviance as everyday life. A scholarly examination of prostitution, suitors and strip clubs in Frankfurt's station district. Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2008, ISBN 978-3-8370-6460-5 .

- Fred Prase, Gabi Koloss, Karl Müller: Feuerteich. Police officer and photographer in Frankfurt's Bahnhofsviertel. Unionsverlag, Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-293-00082-7 .

- Three-part series of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung , category Rhein-Main

- Katharina Iskandar: First the misery, then the chic. May 20, 2007, p. R1

- Thomas Kirn: The covers also fell on the facades. April 29, 2007, p. R1

- Thomas Kirn: Then it became quiet in the bar. April 15, 2007, p. R1

Web links

- My district - my home on YouTube

- Website of the Bahnhofsviertel

- Frankfurt-Bahnhofsviertel: A quarter of the world , article, Die Zeit in September 2016

Individual evidence

- ↑ Statistical Yearbook of the City of Frankfurt am Main 2015, p. 118.

- ↑ Railway Directorate in Mainz (ed.): Official Gazette of the Railway Directorate in Mainz of August 20, 1921, No. 50. Announcement No. 924, p. 539.

- ↑ journal-frankfurt.de

- ↑ Katharina Iskandar: Frankfurter Bahnhofsviertel: The anger in the district is growing . In: FAZ.NET . ISSN 0174-4909 ( faz.net [accessed August 4, 2020]).