Air raids on Japan

| date | April 18, 1942 to August 15, 1945 |

|---|---|

| place | Japanese main islands |

| output | Allied victory |

| consequences | Allied occupation of Japan |

| Peace treaty | Surrender of Japan , Peace Treaty of San Francisco |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Troop strength | |

|

|

|

| losses | |

|

Fifth Air Force: 31 aircraft |

Between 241,000 and 900,000 dead (estimates) |

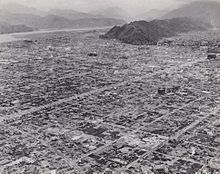

The Allies carried out numerous air strikes on Japan during the Pacific War , which destroyed many of the country's cities and killed at least 241,000 people. In the first years after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor , these air strikes were limited to the Doolittle Raid in April 1942 and minor attacks against military positions in the Kuril Islands from mid-1943. The strategic bombardment of the islands began in June 1944 and lasted until the end of the Combat operations on August 15, 1945. Due to the advance of the war front on Japan, the air strikes in the course of 1945 were additionally supported by sea and land-based tactical air units .

Air strikes by the United States' armed forces began on a large scale from mid-1944 and increased in scope and intensity, particularly during the final months of the war. Despite planning in the pre-war period, the US Army Air Forces could only begin the planned strategic bombing after receiving the technically superior B-29 bomber . For this type a separate air fleet, the Twentieth Air Force, was created. From June 1944 to January 1945 the B-29 units were stationed in British India and flew to Japan from there, with refueling stops in the non-Japanese-occupied part of China. However, these long haul flights turned out to be ineffective. From November 1944, strategic bombing was expanded considerably after the Marianas had been captured and the airfields there became available. The attacks were originally directed mainly against industrial facilities and from March 1945 onwards were generally aimed at urban areas. Carrier-based and after the conquest of Okinawa started bombers attacked in 1945 in addition to Japan, the October 1945 planned invasion of the main islands prepare. At the beginning of August 1945, American bombers from special unit 509 dropped . Nuclear bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki .

Japan's military and civil defense were unable to stop the Allied air strikes. The number of fighter planes and anti-aircraft guns stationed on the main islands turned out to be too low. To make matters worse, most of the aircraft and cannon types used did not reach the altitude at which the B-29 flew. Other reasons for the ineffectiveness of the Japanese fighter squadrons were a lack of fuel, poor pilot training and a lack of coordination between the individual units. Despite the threat to Japanese cities from being dropped by fire bombs , the Japanese fire protection units were poorly equipped and poorly trained. Likewise, only a few air raid shelters were available for the civilian population . These weaknesses made it possible for the Allies to destroy many Japanese cities on a large scale and to suffer only minor losses.

The Allied air strikes were one of the main factors that led to the surrender of Japan in mid-August 1945 . Since the end of the war there have been long-term debates about the moral justification for attacks on Japanese cities. The use of the atomic bombs against Hiroshima and Nagasaki was particularly controversial. The most frequently cited estimates of the victims among the Japanese population assume around 333,000 dead and 473,000 wounded, other estimates vary between around 241,000 and 900,000 dead and 213,000 and 1.3 million wounded. In addition to these population losses, the air strikes devastated many urban areas and resulted in a huge decline in industrial capacity.

background

United States plans

The United States Army Air Corps , which was transformed into the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) in February 1942 , began developing plans for an air war against Japan in the course of 1940 in the event of war between the two countries. That year, the naval attaché at the United States Embassy in Tokyo reported that civil defense in Japan was weak.

Plans were also developed to enable American Air Force volunteers to serve on the side of the Chinese armed forces in the Second Sino-Japanese War . At the end of 1941, the Flying Tigers, the first American Volunteer Group (AVG), began their service in China as part of the Chinese Air Force, using American Curtiss P-40 fighter aircraft . A second AVG was also set up in late 1941 and equipped with Lockheed Hudson and Douglas A-20 bombers , with which Japan was planned to attack from bases on mainland China. After the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 and the subsequent declaration of war by the United States on the Japanese Empire, such covert air operations were no longer necessary, which is why the second AVG was not activated and its aircraft were used for other purposes. The personnel of the 2nd AVG, which were already partially embarked in November 1941, were in Australia when the war broke out , where they initially remained.

The Japanese successes and the associated advance in the first months of the war nullified the American pre-war plans to bomb the main islands. Plans to bomb the main islands from mainland China could not be implemented either. Before the war, USAAF had planned to fly its attacks from Guam , the Philippines and Wake . All of these areas quickly fell under Japanese control and most of the USAAF heavy bombers stationed in the Philippines fell victim to an air strike on Clark Air Base on the Philippines' Luzon island. In March and April 1942, the USAAF attempted to move 13 heavy bombers to China to bomb the main islands. These reached British India and were not moved from there, as the Japanese invasion of Burma made logistical support for the bombers in China difficult and the Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek was opposed to attacks on Japan from the area under his control at the time. In May 1942 another 13 Consolidated B-24 heavy bombers were marched in the direction of China, although they were given the new task of supporting the Allied operations in the Mediterranean region while they were being moved . In July 1942, the commander of the AVG, Colonel Claire Lee Chennault , called in a total of 100 Republic P-47 fighter jets and 30 North American B-25 medium bombers , which he believed would "destroy" the Japanese aircraft industry can. Three months later, Chennault reported to US President Franklin D. Roosevelt that a force of 105 modern fighter jets and 40 bombers, including 12 heavy bombers, would be able to "bring about the fall of Japan [in six to twelve months]." USAAF headquarters found these allegations unbelievable, which is why Chennault did not receive the reinforcements requested.

Japanese pre-war defense plans

The Japanese government's pre-war plans to protect the country from air raids focused on eliminating enemy air bases. In these plans, Soviet planes operating from the east of the country were the most dangerous enemy. Therefore, in the event of war between the two countries, the military planned to destroy all Soviet airfields within range of the main islands. After the war against the United States began, the Japanese government considered it the best idea to capture the areas in China and the Pacific from which bombers could reach the main islands in order to prevent air strikes. These plans assumed that the Allies would not be able to retake the bases. The Japanese expected only minor attacks from carrier-based aircraft against the islands. The government decided not to make strong defensive preparations against such attacks because the industrial capacities required were insufficient to support both the offensive air forces in China and the Pacific and a defense force on the main islands.

Few air units or anti-aircraft batteries were stationed on the main islands in the first months of the war. In July 1941, the military leadership formed the Central Defense Command to coordinate the defense of the islands. However, this had to hand over the command of all combat units to the four formally subordinate military districts ( North , East , West and Central ), which in turn reported directly to the Army Ministry . As a result, the Central Defense Command was only responsible for coordinating communications between the Imperial General Headquarters - Japan's highest military leadership body - and the military districts. At the beginning of 1942, the units deployed to protect the main islands had 100 warplanes of the Imperial Japanese Army Air Forces and 200 of the Navy Air Forces , most of which were out of date. In addition, there were 500 anti-aircraft guns manned by army personnel and 200 by naval personnel . Most of the units on the main islands were used to train new flight personnel, which meant that they were only suitable to a limited extent for repelling enemy air attacks. The army also operated a network of observation posts manned by soldiers and civilians, who were supposed to report approaching enemy aircraft, and built the first radar stations. Command and control over the air defense were thus dispersed between the individual armed forces and neither the army nor the navy tried to coordinate their actions or to improve communication. As a result, the forces deployed were mostly unable to respond to a surprising air attack.

Due to the prevailing architecture and the weak civil defense, the Japanese cities were at great risk from the potential use of incendiary bombs. Urban areas were typically densely populated and most buildings were constructed from easily flammable materials such as wood or paper. In addition, industrial and military facilities were often located in densely populated areas. Despite this danger, only a few cities had trained professional fire brigades and instead relied on the use of volunteers. The volunteer fire brigades often had little new equipment and in the event of a fire they used outdated fire fighting tactics. Regular air raid drills had been carried out in Tokyo and Ōsaka since 1928, and from 1937 instructions were issued to the local authorities to provide the civilian population with manuals explaining the best behavior in the event of air raids. In the run-up to the war, only a few air raid shelters and other protective facilities for civilians and industry had been built in the country.

Early attacks

Doolittle Raid

In mid-April 1942, USAAF aircraft bombed the main Japanese islands for the first time. In an operation that was mainly intended to increase American morale in the war, 16 B-25 bombers on board the aircraft carrier USS Hornet were brought into striking range from San Francisco . On April 18, these bombers took off and individually attacked targets in Tokyo, Yokohama , Yokosuka , Nagoya and Kobe . The air defense was not prepared for this attack and could only react slowly, which meant that all B-25s could fly over Japan without serious damage and head for airfields in unoccupied China and the Soviet Union as planned. However, on the way to the landing sites, some of the planes crashed over Japanese-owned territory because they ran out of fuel. This first air strike killed 50 people, injured 400 more and destroyed around 200 houses.

Although the Doolittle Raid did little damage, it had significant consequences. The attack raised general morale in the United States, and the operation commander, Lt. Col. James H. Doolittle , was viewed as a hero. The poor state of the national air defense embarrassed the Japanese military leadership and led to the relocation of four fighter squadrons from the Pacific region to defend the main islands. The newly launched offensive of the Imperial Navy, which culminated in the defeat in the Battle of Midway , was, among other things, an attempt to prevent further such attacks in the future. For its part, the army launched the Zhejiang-Jiangxi campaign in China to conquer the airfields used by the Doolittle bombers. The campaign achieved its objectives and resulted in the deaths of approximately 250,000 Chinese soldiers and civilians, with repeated war crimes committed by Japanese forces against civilians. In addition, the army began developing balloon bombs , which should be able to carry incendiary and anti-personnel bombs from Japan to the American continent.

Attacks on the Kuril Islands

After the Doolittle Raid, Japanese territory was not attacked again from the air until mid-1943. After the recapture of Attu Island in May 1943 as part of the Battle of the Aleutian Islands , the USAAF owned airfields that were within reach of the Kuril Islands. As part of the preparations to retake Kiska Island , the Eleventh Air Force launched a series of attacks against the Kuril Islands to prevent the air squadrons stationed there from engaging in the fighting. A numbered Air Force as part of the USAAF was roughly equivalent to an air fleet in the Wehrmacht . The first of these attacks was made by eight B-25s on July 10th against southern Shumshu and northern Paramushiru . On July 18, six B-24 heavy bombers flew another attack on the Kuril Islands. On August 15, the American troops were able to occupy Kiska without resistance .

The Eleventh Air Force and US Navy units continued their small-scale attacks on the Kuril Islands into the final months of the war. After an attack on September 11, 1943, which resulted in the loss of nine of the 20 deployed B-24 and B-25 bombers, the Eleventh Air Force suspended its attacks for five months, while US Navy bombers of the Consolidated PBY type the Continue bombing without interruption. In response to the American attacks, the Imperial Navy set up the northeastern regional fleet in August 1943 and by November of that year there were a maximum of 260 fighter aircraft on the Kuril Islands and Hokkaidō . The Eleventh Air Force resumed bombing in February 1944 after adding two squadrons of Lockheed P-38 escort fighters. Although these attacks caused little damage, they forced the Japanese military leadership to station a comparatively large number of troops on their northern islands in order to be able to counter a possible Allied invasion.

Operation Matterhorn

Preparations

In late 1943, the Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy , William D. Leahy, agreed to plan a strategic bombing campaign against the main Japanese islands. For this purpose, B-29 bombers should be stationed in British India and advanced airfields should be set up in China. This strategy, called Operation Matterhorn , led to the construction of large airfields near Chengdu , which were to be used to refuel the B-29s flying from their bases in Bengal to Japan and back. Chennault, who was now commander of the Fourteenth Air Force , advocated the construction of the airfields near Guilin , as it was closer to Japan. However, his proposal was rejected on the grounds that these positions were too vulnerable to Japanese counter-attacks. The decision for Chengdu, however, meant that only the southern main island of Kyūshū was within the 2,600-kilometer-wide attack radius of the B-29.

In December 1943, the ground personnel of the XX Bomber Command designated for Operation Matterhorn began to be transferred from the United States to India. In April 1944, the Twentieth Air Force was formed to coordinate all B-29 operations. The USAAF Commander-in-Chief, General Henry H. Arnold , took over, which had not happened before, personal command of the newly established large association and exercised the supreme command of the Department of Defense . Between April and mid-May 1944, the 58th Bombardment Wing , the main combat unit of the XX Bomber Command, moved from its bases in Kansas to India.

The Japanese military began to move more combat aircraft from China and the Pacific to the main islands from early 1944 in anticipation of B-29 air strikes. The country's military intelligence services reported the establishment of bases in India and China, so the military began planning to fend off air strikes from China. These plans included the increase and reshuffle of the three army air combat groups stationed on Honshū and Kyūshū to form the 10th , 11th and 12th air divisions between March and April 1944. At the end of June, the air defense units on the main islands had 260 combat aircraft and were able to do up in emergencies to draw 500 more aircraft. To defend larger cities and military bases, additional batteries with anti-aircraft cannons and searchlights were installed. In May, the Central Defense Command was strengthened when the army units in the eastern, western and central districts were directly subordinate to it. In addition, the subordinate naval fighter units in Kure , Sasebo and Yokosuka took place in July , but their coordination with the army units remained inadequate. Despite these advances, the air defense remained unprepared for the imminent attacks, as few of the available aircraft and anti-aircraft guns could reach the operating altitude of the B-29 of around 9,100 meters and only a few radar stations were ready for early warning.

In response to the Doolittle Raid and the threat of further attacks, the Japanese government tried to make the country's civil defense more efficient. The prefectural governments were commissioned to build air raid shelters for the civilian population, which was often not possible due to a lack of steel and concrete. In October 1943, the Ministry of the Interior instructed all households in the larger cities to set up their own protective devices, which mostly consisted of simple trenches. A few sophisticated air raid shelters were built to protect the air defense centers and central telecommunications facilities. Overall, however, the country only had bomb-proof bunkers for less than two percent of the population, which therefore avoided tunnels and natural caves during bombing. After the outbreak of war, the Ministry of the Interior began to increase the number of firefighters, but they remained poorly trained and equipped volunteers. In addition, the general population was trained in fighting fires and encouraged to take an “air defense oath” obliging them to come out after a bombing raid and help with fire fighting.

From the fall of 1943, the Japanese government took further steps to protect the country's main cities against air raids. A central air defense headquarters was established in November, and in December many buildings in various cities began to be demolished to create firebreaks . By the end of the war, around 614,000 buildings had been demolished for this purpose, which corresponded to a fifth of the total loss of housing during the war. 3.5 million people lost their homes in the process. In the same month, the government began encouraging women, children and the elderly in cities deemed vulnerable to move to the countryside. At the same time, a program was set up to send entire school classes to more rural areas. By August 1944, 330,000 school children and their classes had been sent to the country and a further 459,000 had moved there with their families. A decentralization of industrial plants in order to make them less susceptible to air attacks hardly took place at all due to logistical difficulties.

Attacks from China

In mid-June 1944, the XX Bomber Command began its attacks on Japan. The first attack took place on the night of June 15-16, when 75 B-29s flew an attack against the Imperial Iron and Steel Works in the city of Yawata on Kyūshū, which did little damage and resulted in the loss of seven B. -29 led. In the United States, the attack attracted rave media attention, while to Japanese civilians it was a sign that the fortunes of war were turning. After the attack on Yawata, the military continued to increase the air defense forces and by October of that year the three air divisions had a permanent force of 375 fighter aircraft. This strength remained almost unchanged until March 1945. Since he could not fly further attacks on Japan due to a lack of fuel reserves in China, General Arnold relieved the commander of the XX Bomber Command, Brigadier General Kenneth Wolfe , of his command shortly after the attack on Yawata and replaced him in August 1944 by Major General Curtis LeMay , the had already gained experience with the Eighth Air Force in the air war against the German Reich .

The subsequent attacks from China generally failed to achieve their goals. The second attack occurred on July 7th when 17 B-29s attacked the cities of Ōmura , Sasebo and Tobata . On the night of August 10-11, 24 bombers attacked Nagasaki. Another attack on Yawata on August 20 was also unsuccessful, with over 100 Japanese fighters intercepting the approaching bombers. Twelve of the 61 B-29s that reached the target area were lost, including one due to a ramming attack by a fighter pilot. As a result of the air battle, Japanese propaganda claimed that over 100 enemy bombers had been shot down and exhibited one of the crashed planes in Tokyo. After taking command, LeMay started a training program and reorganized the maintenance units of XX Bomber Command, which increased efficiency. An attack on Ōmura on October 25th destroyed a small aircraft factory in the city, and a follow-up attack on November 11th turned out to be a failure. On November 21, 61 and on December 19, 17 B-29 attacked the city again. The last attack of the XX Bomber Command over China took place on January 6, 1945, when 28 bombers bombed Ōmura again. At the same time, the XX Bomber Command had also attacked targets in Manchukuo , Taiwan and China from its bases in China . Machines launched from India bombed various targets in Southeast Asia. The last attack before the command was transferred to the Mariana Islands was against Singapore on March 29 .

Overall, Operation Matterhorn was not a success. The nine air strikes on the main islands could only destroy the aircraft factory in Ōmura. In the course of the operation, the XX Bomber Command lost a total of 125 B-29s during its operations, 22 or 29 of them through enemy action. The majority of the losses were caused by crashes as a result of technical defects or pilot errors. The bombings had little effect on Japanese civilian morale, but forced the military to step up home defense at the expense of other regions. These effects did not justify the high material and logistical costs that the Allies invested in the operation. It is more likely that the additional transport planes needed to supply the bases in China would have been more effective in assisting Fourteenth Air Force's operations against Japanese shipping. Official USAAF historiography concludes that the intricate transport of sufficient quantities of supplies to China and India was the most important factor in the failure of Operation Matterhorn. Further reasons were according to this technical problems with the B-29 and the lack of experience of the bomber crews. The often adverse weather conditions over Japan also hindered the bombing, as the B-29 crews were unable to drop their bombs accurately over their target area due to high winds and clouds.

First attacks by the Mariana Islands

Forces of the United States Marine Corps and the United States Army were able to conquer the islands of Guam , Saipan and Tinian in the Mariana Islands between June and August 1944 . As a direct result of the occupation of the islands, construction crews from the USAAF and the US Navy built a total of six airfields, which were to form the base of operations for several hundred B-29s. These bases were only 2,500 kilometers south of Tokyo and could easily be supplied by sea, which made them much more useful than those in China, as any point on the main islands could be attacked. Japanese planes attacked the Saipan base several times while it was still under construction in an unsuccessful attempt to slow down runway construction.

From October 1944 the first units of the XXI Bomber Command of the Twentieth Air Force arrived in the Mariana Islands. The Bomber Command was under the command of Brigadier General Haywood S. Hansell , who like Curtis LeMay had already gained experience with the Eighth Air Force in the air war against the German Reich 1943-1944. In preparation for the first deployment against the main islands, Bomber Command B-29s flew six training missions against targets in the Central Pacific in October and November. On November 1, an F-13 photo reconnaissance aircraft belonging to the 3d Photographic Reconnaissance Squadron , a converted variant of the B-29, flew over Tokyo, making it the first American aircraft to cross the city since the Doolittle Raid. In the following days, more F-13s flew over the Tokyo-Yokosuka area to gather information about the aircraft factories and port facilities there. The high altitude and high speed ensured that the F-13 could avoid the heavy defensive fire and the many Japanese fighters.

The first attacks by the XXI Bomber Command on the main islands were directed against the country's aircraft industry. The first attack, called Operation San Antonio I , took place on November 24th and targeted the Musashino aircraft plant in a suburb of Tokyo. Only 24 of the 111 deployed B-29s bombed the main target, while others dropped their bombs over port and industrial facilities as well as residential areas. The 125 Japanese aircraft launched for defense shot down one of the American bombers in this attack. The bombing damaged the aircraft factory and further weakened the confidence of Japanese civilians in the country's air defense. In response, the Japanese Army and Navy Air Forces increased their attacks on the Marianas from November 27th, where they were able to destroy a total of 11 B-29s on the ground and damage another 43 by their last attack in January 1945. Your own losses during the entire operation were believed to be 37 machines.

The following attacks on the main islands proved to be unsuccessful. The XXI Bomber Command attacked Tokyo three times between November 27 and December 3. Two of the attacks were again directed against the Musashino aircraft plant, while the third targeted an industrial area. This was Napalm - cluster bombs of the type AN-M69 used, which had been specifically designed to attack Japanese cities. The attacks on the aircraft factory on November 27 and December 3 caused only minor damage, as winds at high altitude and thick clouds prevented a targeted bombardment. The incendiary attack carried out by 29 bombers on the night of November 29th to 30th and the subsequent fires destroyed an area of about a quarter of a square kilometer. It was also rated unsuccessful by the headquarters of the Twentieth Air Force.

Four of the next five attacks were against Nagoya . The first two bombings, on December 13th and 18th, consisted of precision bombing of the city's aircraft factories. The third was a daytime incendiary attack. This was carried out after the Twentieth Air Force requested an attack by 100 bombers equipped with the AN-M76 bomb to test the effectiveness of this new incendiary bomb against Japanese cities. Brigadier General Hansell protested the attack, believing that precision bombardment was already beginning to have an effect and the transition to area bombing could be counterproductive. After being assured that this attack was not a general change in tactics, he agreed. Despite the different armament, 78 bombers carried out the attack on December 22nd as a precision bombardment of the aircraft industry. Bad weather ensured that only minor damage was caused. On December 27th, the XXI Bomber Command flew another attack on the Musashino aircraft plant, but could not hit it. On January 3, 1945, 97 B-29s flew an area attack against Nagoya, which caused several fires in the city, but they were quickly brought under control. At the end of December 1944, General Arnold, who was dissatisfied with the performance of the XXI Bomber Command under Brigadier General Hansell, decided to replace it with Curtis LeMay. He justified his decision with the fact that he wanted to achieve visible results of the air strikes as quickly as possible. In addition, Hansell's preference for precision bombing no longer fit into the tactics of the Twentieth Air Force headquarters, which wanted a shift towards more area bombing. Due to his good performance as commander of the XX Bomber Command, LeMay was considered the ideal candidate to solve the problems of the XXI Bomber Command. Hansell learned of Arnold's decision on January 6, but remained at his post until the middle of the month. In the meantime, the XXI Bomber Command carried out further precision attacks on the Musashino aircraft plant and a Mitsubishi aircraft plant in Nagoya on January 9 and 14, respectively , which were considered unsuccessful . The last air raid planned by Hansell was considered a success. On January 19, 77 B-29s successfully attacked a Kawasaki aircraft plant near Akashi . During the first three months of operation against the main islands, the XXI Bomber Command had an average loss rate of 4.1 percent per mission.

At the end of January 1945, the Imperial Headquarters belatedly passed a civil defense plan against the American air raids. This plan transferred fire fighting responsibility to local councils and neighborhood workers as there was a shortage of trained firefighters. In addition, a general blackout from 10 p.m. was agreed. Observation posts on the Bonin Islands were able to warn of approaching groups of bombers with about an hour's advance warning, whereupon aerial alarms were given in the cities classified as endangered.

The first air strikes under the command of Curtis LeMay led to different results. The XXI Bomber Command flew six major attacks between January 23 and February 19, which were classified as less successful, although an incendiary bombing raid on Kobe on February 4 resulted in greater destruction in the city and its war industries. Although LeMay reorganized the maintenance crews, which resulted in fewer bombers having to abandon their attacks due to technical problems, the loss rate in these operations rose to 5.1 percent. From February 19 to March 3, the XXI Bomber Command carried out precision attacks against various aircraft factories in order to bind Japanese fighters over the main islands and thus prevent them from intervening in the battle of Iwo Jima . High winds and clouds ensured that only minor damage was caused. An incendiary attack with 172 bombers on Tokyo on February 25 destroyed approximately 2.5 square kilometers of residential areas in the city. This attack was carried out as a large-scale test to determine the effectiveness of incendiary bombardment.

Various factors are used to explain the poor effectiveness of the XXI Bomber Command's precision attacks. The most important is the weather, as the attacks were often hampered by high winds prevailing over Japan and thick clouds, which made it difficult to accurately drop the bomb. Bad weather fronts between the Mariana Islands and Japan also led to the bomber formations disintegrating and navigation problems. Poor maintenance and overcrowding of the available bases were other reasons. They reduced the number of bombers available for attack and complicated the complex take-off and landing process of large bomber formations.

Incendiary attacks

LeMays change of tactics

USAAF tacticians had already begun in 1943 to examine the possibility of a successful aerial campaign against Japanese cities using incendiary bombs. The majority of the Japanese industrial facilities were directly threatened by this, as they were concentrated in a few large cities. In addition, a large part of the production took place at home or in small factories directly in the residential areas of the cities. USAAF planners estimated that incendiary bombing attacks on the six largest cities in the country could damage up to 40 percent of industrial facilities and, as a result, 7.6 million man-hours could be lost in manufacturing. Furthermore, more than 500,000 dead, around 7.75 million homeless and 3.5 million evacuees were expected in these plans. The USAAF tested the effectiveness of the incendiary bombs to be used on Japanese-style buildings in Eglin Field and in the so-called "Japanese village" on the Dugway Proving Ground . At that time, the American military was also working on a project to create bat bombs, in which bats with small incendiary bombs were to be dropped over Japanese cities. This project was discontinued in 1944.

Due to the poor results of the precision bombing and the success of the fire bombing attack on Tokyo on February 25, General LeMay decided to launch further such attacks against the main Japanese cities from the beginning of March. This was in line with General Arnold's target directive for the XXI Bomber Command, according to which urban areas were given the second highest priority after aircraft plants. The directive also stipulated that the incendiary attacks should begin as soon as the AN-M69 Napalm bomb had been tested in combat and enough bombers were available to enable intensive bombing. Before the fire bombing began, General LeMay refrained from obtaining permission from General Arnold in order to protect him from criticism in the event of failure. Brigadier General Lauris Norstad , Chief of Staff of the Twentieth Air Force, heard about this change of tactics and provided support for it. To maximize the effectiveness of the attacks, LeMay ordered the bombers to fly at an altitude of 1,500 meters and attack at night. This represented a reversal of the previous attack tactics of the Bomber Command, which had previously provided for daytime attacks from great heights. Since Japan's night fighter force was weak, LeMay had most of the anti- aircraft cannons removed from the B-29 so that they could carry more bombs due to the reduced weight. The flight crews of the XXI Bomber Command were critical of the changes because they believed it was safer to fly heavily armed and at high altitude.

Fire bombing raids in March 1945

The first incendiary attack took place on the night of March 9-10 on Tokyo and turned out to be the most devastating single air strike of World War II. The XXI Bomber Command gathered all available forces and launched 346 bombers from the Mariana Islands on the afternoon of March 9th. From 2 a.m. Guam time, these began to reach the city and 279 B-29s dropped a total of 1,665 tons of bombs. The civil defense of the city was unable to counter the resulting firestorm , so that 41 square kilometers, which corresponded to seven percent of the city's area, burned down. Japanese police estimated that the attack and fires killed 83,793 people, wounded 40,918 and left over a million homeless. Post-war estimates assume 80,000 to 100,000 deaths. The damage to Tokyo's infrastructure was considerable. The Japanese attempts to defend themselves against the attack were relatively weak. 14 B-29s were lost to combat or mechanical failure, and a further 42 were damaged by anti-aircraft fire. In response to the destruction of Tokyo, the Japanese government ordered the evacuation of all third to sixth grade school children from major cities in the country. By early April, 87 percent of these children had been sent to more rural areas.

In the days that followed, the XXI Bomber Command carried out further attacks on various cities. On March 11, 310 bombers flew against Nagoya. The attack was spread over a larger area than that against Tokyo and did less damage. 5.3 square kilometers of urban area burned down, while none of the bombers were lost to enemy action. On the night of March 13-14, 274 B-29s attacked Osaka , destroying 21 square kilometers of the city and losing only two aircraft. The next target selected was Kobe, which was bombed by 331 B-29s on the night of March 16-17. With their own losses of three machines, the bombers destroyed 18 square kilometers, which corresponded to half of the urban area. Another attack on Nagoya on the night of March 18-19 destroyed a further 7.6 square kilometers of the city. A B-29 crashed as a result of enemy fire over the open sea, and the entire crew could be saved. The second attack on Nagoya marked the temporary end of the intensive incendiary bombing, as the XXI Bomber Command had used up its supplies of incendiary bombs. The next attack was a precision night bombing of a Mitsubishi aircraft engine plant from March 23rd to March 24th. The mission failed and the Japanese air defense was able to shoot down five of the 251 attacking bombers. Also in March, B-29s began dropping propaganda leaflets calling on the Japanese people to overthrow their government or face annihilation.

USAAF rated the March incendiary bombing strikes very successful, noting that casualty rates were much lower than the daylight precision strikes. Based on these evaluations, the Joint Target Group (JTG), the Washington, DC-based organization that develops strategies for the bombing of Japan, began developing a two-stage plan for operations against 22 Japanese cities. She also recommended that precision attacks against particularly important industrial plants be carried out in parallel. While the continued air strikes were seen in preparation for the Allied invasion of Japan, LeMay and some members of General Arnold's staff believed that they alone could surrender the country.

The Japanese government was concerned about the air strikes and the damage they caused because the military had proven unable to seal off the airspace. In addition to the physical destruction, many people no longer dared to leave their homes and go to work because they feared the factories would be bombed. In response to the attacks, the military strengthened the air defense, but it remained too weak; In April, 450 fighter planes were deployed on the main islands for air defense purposes.

Destruction of Japan's main cities

Further extensive incendiary bombing attacks were delayed, as the XXI Bomber Command attacked airfields in southern Japan from late March to mid-May in order to cover the Allied landing on Okinawa immediately south of the main islands. Before the start of the landing on April 1, the command attacked airfields at Ōita and Tachiarai on March 27 and 31, and an aircraft factory at Ōmura on March 27 without losses of its own. On April 6, powerful Japanese air forces attacked the Allied invasion fleet off Okinawa using kamikaze tactics and were able to damage or destroy many ships in the process. In response, the XXI Bomber Command launched raids on airfields in Kyushu on April 8-16. The April 8 attack groups changed their target during the approach because the target airfields were under thick cloud cover, and instead bombed residential areas in the city of Kagoshima . From April 17 to the release of the B-29 on May 11, much of the XXI Bomber Command continued to bomb airfields and other facilities supporting the Japanese armed forces in Okinawa. A total of 2,104 flight missions against 17 airfields took place during this period, 24 bombers were lost and 233 were damaged. The XXI Bomber Command failed to completely stop the kamikaze attacks from the bombed airfields.

During the early stages of the Battle of Okinawa, there were still isolated attacks on Japanese cities. On April 1, 121 B-29s carried out a nighttime precision attack on the Nakajima engine plant in Tokyo and on April 3 on engine plants in Koizumi, Shizuoka and Tachikawa . Since the bombers of the XXI Bomber Command lacked special equipment for precise night bombing, the attacks failed, which led LeMay to discontinue this type of attack. Smaller Command units attacked Tokyo and nearby Kawasaki on April 4 . On April 7, it flew two large-scale, successful precision attacks against Nagoya and Tokyo. The unit flying against Tokyo was the first to receive escort from VII Fighter Command long-range P-51 fighters stationed on Iwo Jima . After the attack, the Americans claimed to have shot down Japanese aircraft with the loss of two P-51s and seven B-29s. More than 250 bombers attacked three different aircraft factories on April 12th, with the 73rd Bombardment Wing severely damaging the Musashino aircraft factory and repelling 185 attacking fighter planes without losses. On April 13, LeMay ordered nightly incendiary bombing to continue, and that same night, 327 B-29s bombed Tokyo, destroying 30 square kilometers of urban space, including several armaments factories. Two days later on April 15, 303 bombers destroyed 16 km² in Tokyo, 9.3 km² in Kawasaki and 3.9 km² in Yokohama, with losses of 12 aircraft. 131 bombers completely destroyed the engine plant in Tachikawa near Tokyo on April 24th. An attack on the aircraft arsenal in Tachikawa six days later had to be canceled due to heavy cloud cover over the target. Instead, some of the approaching bombers attacked the city of Hamamatsu on their return flight . On May 5, 148 B-29s wreaked havoc on the Hiro naval aircraft plant near Kure. Five days later, the command carried out successful attacks on oil deposits at Iwakuni , Ōshima and Toyama . On May 11, a small association destroyed an aircraft frame factory near Konan. The XXI Bomber Command reached full strength with the arrival of the 58th and 315th Bombardment Wing in the Mariana Islands in late April. At this point in time it was subordinate to five squadrons with a total of 1,002 B-29s, making it the most powerful air unit in the world.

After the end of the attacks on Okinawa, the XXI Bomber Command began intensive fire bombing against Japan's most important cities in mid-May. On May 13, 472 B-29s destroyed an area of 8.2 km² in a daytime attack in Nagoya. The strong Japanese defense was able to shoot down two bombers and damage another 64 in this attack. Eight other aircraft were lost for other reasons. The Americans assumed they had safely 18 enemy fighters and possibly shot down another 30; 16 thought they were damaged. On the night of May 16, 457 bombers attacked Nagoya again and destroyed 9.9 km² of the city area. The Japanese night defense was significantly weaker than that during the day and could not shoot down any of the attacking bombers. Only three were lost due to technical defects. In the two attacks on Nagoya, 3,866 Japanese died and a further 472,701 were left homeless. On May 19, 318 B-29 flew an unsuccessful precision attack against the factory of the aircraft manufacturer Tachikawa Hikōki . As a result, the XXI Bomber Command carried out large-scale attacks on Tokyo on the nights of 23 and 25 May. In the first attack, the command destroyed 14 km² in southern Tokyo with 520 bombers, with 17 aircraft being lost and 69 damaged. For the second attack, 502 planes took off and set fire to 44 km² in central Tokyo, including some government ministerial buildings and large parts of the imperial palace . In advance, the bomber crews had been ordered not to aim at the palace, since the US government did not want to risk killing Tennō Hirohito . The Japanese air defense was comparatively successful and was able to shoot 26 Superfortresses and damage another 100. After the two attacks, 50.8% of Tokyo was in ruins, so the XXI Bomber Command removed it from its target list. The last major attack by the Command in May was a daytime fire attack on Yokohama, carried out on May 29 by 517 B-29s, covered by 101 P-51s. 150 A6M fighter planes intercepted the formation. In the ensuing air battle, they shot down five American bombers and damaged another 175. The pilots of the P-51 then reported 26 safe and 23 possible enemy kills. The 454 Superfortresses that reached Yokohama destroyed 18 km² of the city's main commercial district. In total, the attacks by the XXI Bomber Command and the fires they triggered destroyed 240 km² of built-up area, which corresponds to a seventh of the total urban area of Japan. Interior Minister Yamazaki Iwao concluded after the attacks that the preparations for the Japanese civil defense had been ineffective.

The incendiary attacks against the main cities continued until mid-June. On the first of the month, 521 of 148 P-51 escorted B-29s bombed Osaka by day. Dense clouds led to the loss of 27 P-51s, which collided with each other in poor visibility. 458 bombers and 27 long-range fighters reached the city and attacked it, 3,960 people died and 8.2 km² of the city area burned down. On June 5th, 473 bombers flew an attack against Kobe during the day and destroyed 11.3 km² of built-up area with the loss of 11 planes. In the attack on Kobe, 3,614 Japanese died, an additional 10,046 were wounded and 51,399 buildings were destroyed. On June 7th, another attack with 409 B-29s on Osaka followed, which destroyed 5.7 km². On June 15, the fourth air raid on Osaka took place when 444 aircraft destroyed 4.9 km² there and 1.5 km² in nearby Amagasaki . This bombardment marked the end of the first phase of the XXI Bomber Command's air strikes on Japan's cities. In May and June, the command destroyed large parts of the country's six largest cities; between 112,000 and 126,762 people died and several million lost their homes. The widespread destruction and the high number of casualties led many Japanese to realize that the military was no longer able to effectively defend the main islands. The American losses were minimal compared to the Japanese; only 136 B-29s were lost.

Attacks on small towns

In mid-June General Arnold visited LeMay's headquarters on Saipan. During his stay, he approved a plan to attack 25 smaller cities between 62,280 and 323,000 inhabitants while continuing to carry out precision attacks against the largest cities. He preferred the plan over one proposed by the United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS). The USSBS had analyzed the effectiveness of the air strikes on the German Reich and, based on the knowledge gained, recommended focusing the attacks on the Japanese transport system in order to hinder the transport of goods and to paralyze the transport of food to the metropolitan areas. LeMay's plan provided for precise attacks on industrial plants in good weather and daylight and radar-guided incendiary attacks at night. Since the chosen targets were relatively small, the XXI Bomber Command no longer attacked a single target with all its might, but instead sent smaller groups against different targets on attack days. This target selection, called the Empire Plan , remained in force until the end of the war.

Five large-scale precision attacks took place under the Empire Plan . On June 9, two groups attacked an aircraft factory near Narao (today: Shinkamigotō ) and two others attacked a factory in Atsuta . Both plants were seriously destroyed. A single group flew to a Kawasaki aircraft plant near Akashi, but instead accidentally bombed a nearby village. The following day, six groups escorted by 107 P-51s flew attacks on as many factories around Tokyo Bay. The next attack came on June 22nd when 382 B-29 bombed targets in Akashi, Himeji , Kakamigahara , Kure and Mizushima. Most of the factories attacked suffered severe damage. Four days later, LeMay sent 510 bombers and 148 escort fighters against nine factories in southern Honshu and Shikoku. Dense cloud cover over the target area meant that the crews dropped their bombs individually or in small groups over the target if they saw a chance to meet. As a result, the actual targets suffered only a few hits. Persistent cloudiness prevented further large-scale precision attacks until July 24, when 625 Bomber Command aircraft hit seven targets in the Nagoya and Osaka regions. Four factories were badly destroyed. Another cloudy weather prevented further implementation of the Empire Plan until the end of the war.

The XXI Bomber Command began its incendiary raids on smaller towns on the night of June 17th. That night, a squadron each attacked the cities of Hamamatsu , Kagoshima, Ōmuta and Yokkaichi on the same principle that had already been used to destroy the larger cities. 456 of 477 launched bombers reached their targets and sparked a firestorm that burned down 15.73 km² of built-up area. The cities had almost no protection and none of the American planes was lost to Japanese influence. The leadership of Bomber Command viewed this attack as a success and used it as a model for further operations. In the further course of the fire bomb campaign, the attacks were directed against increasingly smaller and less important cities due to the extensive destruction of the previous targets. The command flew most of the attacks against four cities per mission, each of which was bombed by a squadron. Missions with two squadrons each took place on June 19 against Fukuoka and on July 26 against Ōmuta. By the end of the war, the XXI Bomber Command had carried out 16 attacks, which corresponds to an average of two attacks per week, against 58 different cities. In the last weeks of the war, the command coordinated the incendiary bombing attacks with the precision attacks in order to persuade the Japanese government to surrender. Since the smaller cities had no anti-aircraft batteries and the Japanese night fighters operated ineffectively, only one B-29 crashed during the attacks due to enemy action. 66 were damaged and another 18 were lost in accidents.

The Americans continued the fire bombing raids through June and July. They attacked Fukuoka , Shizuoka, and Toyohashi on the night of June 19, and Moji , Nobeoka , Okayama, and Sasebo on June 28 . On July 1 and 3, the bombers bombed Kumamoto , Kure, Shimonoseki and Ube and Himeji , Kōchi , Takamatsu and Tokushima, respectively . On July 6, attacks were flown against Akashi, Chiba , Kofu and Shimizu and on July 9 against Gifu , Sakai , Sendai and Wakayama . Three nights later, the attacks were aimed at Ichinomiya , Tsuruga , Utsunomiya and Uwajima . On July 16, Hiratsuka , Kuwana , Namazu and Ōita and on July 19, Choshi , Fukui , Hitachi and Okazaki were attacked by the bombers. After a break of nearly a week, the bombers dropped incendiary bombs on Matsuyama , Ōmuta and Tokuyama on July 26 .

The aircraft of the XXI Bomber Command dropped large quantities of propaganda leaflets in parallel with their bombing raids. It has been estimated that 10 million leaflets were dropped in May, 20 million in June and 30 million in July. The Japanese government imposed harsh penalties for civilians keeping these leaflets. On the night of July 27th to 28th, six B-29s dropped leaflets over 11 cities announcing the bombing of them. The purpose of this was to lower civilian morale and create the impression that the United States was trying to minimize collateral damage. Six of these cities ( Aomori , Ichinomiya, Tsu , Uji-Yamada , Ōgaki and Uwajima) attacked the Bomber Command the following night. Despite the warning, no bombers were lost to enemy action. Six suffered damage from 40 to 50 attacking Japanese fighters and five others from anti-aircraft fire.

In August, the Bomber Command resumed its incendiary raids. On the night of the 1st, 836 B-29s threw 6,145 tons of bombs and air mines on Hachiōji , Mito , Nagaoka and Toyama in the heaviest single air raid of World War II and severely destroyed the cities. In Toyama, 99.5% of the buildings were destroyed after the attack. Imabari , Maebashi , Nishinomiya and Saga were attacked on August 5th. These attacks were also announced through leaflets and radio broadcasts from Saipan.

From the end of June, the 315th Bombardment Wing carried out nocturnal precision attacks against the Japanese oil industry, independently of the other attacks by the XXI Bomber Command. The squadron's aircraft had previously received advanced AN / APQ-7 radar systems with which they could precisely locate their targets at night. After arriving on the Mariana Islands in April 1945, the squadron underwent training on the new equipment and completed training flights before attacking the Utsube oil refinery near Yokkaichi on the night of June 26th. 30 of 38 bombers launched reached the target and destroyed 30 percent of the refinery. Bombardments on June 29 and July 2 targeted refineries near Kudamatsu and Minoshima . On the night of July 26th to 27th, the squadron destroyed the Maruzen oil refinery near Osaka and three nights later the remains of the Utsube oil refinery. By the end of the war, the 315th Bombardment Wing carried out 15 attacks on nine targets and destroyed six of them. Four B-29s were lost. Since there was almost no crude oil to refine on the main islands due to the Allied naval blockade, these attacks had little effect on the Japanese war effort.

In mid-July, USAAF's strategic bomber units in the Pacific were reorganized. The XXI Bomber Command was transformed into the Twentieth Air Force on July 16 and LeMay was appointed its commander. Two days later, the United States Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific (USASTAF) was formed under the command of General Carl A. Spaatz on Guam. The task of the USASTAF was to exercise supreme command over the Twentieth and the Eighth Air Force, which was in the process of moving from Europe to Okinawa. The Eighth Air Force was under the command of James Doolittle, who had meanwhile been promoted to general, and received the B-29 as the new standard bomber at that time. The Tiger Force , which was made up of Australian, British and New Zealand associations and attacking Japan from Okinawa and was scheduled to arrive at the theater of war at the end of 1945 , should also be subordinated .

Sea mine drops

Since mid-1944, the US Navy has been urging the USAAF to drop their bomber sea mines in the waters around the main islands in order to reinforce their sea blockade. General Arnold and his staff were initially opposed to this request as they were of the opinion that such missions would tie up too many B-29s that were needed for precision attacks. After repeated requests from the Navy, Arnold decided in November 1944 to drop sea mines as soon as he had enough aircraft. In January 1945, LeMay selected the 313th Bombardment Wing as a unit of the Twentieth Air Force specializing in naval dropping. The Navy supported this unit from then on with training and logistics. The corresponding operation was named Starvation by LeMay . Since the United States had used only a few sea mines up to this point during the war, the modernization of the Japanese anti-mine defense had only taken a low priority, so that the Japanese Navy was poorly prepared for the large-scale drops of the USAAF.

The first deployment of the 313th Bombardment Wing took place on the night of March 27-28 and aimed at the Kammon Strait to close it off to Japanese warships that were to attack the American landing forces off Okinawa. The Wing did not mine the main islands in April as it was used in support of the Battle of Okinawa and land attacks. Large-scale attacks, which were directed against ports and maritime bottlenecks, resumed in May. The mines dropped cut off a large part of Japanese coastal shipping.

In June, LeMay increased the number of mine operations and deployed the 505th Bombardment Group for this as well. In response to the drops, the Japanese increased their mine defense by 349 ships and 20,000 men and placed additional anti-aircraft guns around Kammon Street. The laid minefields could not be permanently cleared despite the reinforcements and only a few B-29s could be shot down. Many of Japan's most important ports, including Tokyo, Nagoya and Yokohama, could not be used for shipping on a permanent basis. In the last weeks of the war, the bombers used continued to drop many sea mines around the main islands and extended their operational radius to the waters around the Korean peninsula. When Japan surrendered, the 313th Bombardment Wing had lost 16 of its B-29s in operations. The mines dropped by bombers under LeMay's command sank 293 ships, accounting for 9.3 percent of all Japanese merchant ship losses during the war and 60 percent of losses between April and August 1945. After the war, the USSBS came to the conclusion that the Twentieth Air Force should have focused more on attacks on Japanese shipping for efficiency.

Air strikes by carrier-supported formations

The US Navy carried out the first carrier-based air raids on the main islands in mid-February 1945. The aim of the attacks carried out by Task Force 58 (TF 58) was to destroy Japanese aircraft that could attack the American forces landing on Iwo Jima from February 19 . The TF 58, the US Navy's most powerful offensive formation in the Pacific, consisted of 11 aircraft carriers , five light carriers and strong escorts at the time. The TF 58 penetrated Japanese waters undetected and attacked airfields and aircraft plants in the Tokyo region on February 16 and 17. After the attacks, American pilots claimed 341 kills and 160 aircraft destroyed on the ground. The own losses amounted to 60 kills and 28 pilots lost in accidents. In addition, the planes attacked various ships in Tokyo Bay and sank some of them. The actual Japanese losses from the attacks are unclear; the Imperial Headquarters gave its own losses as 78 aircraft shot down and no figures for those destroyed on the ground. The TF 58 left the waters around the main islands on February 18 for Iwo Jima without being attacked. Bad weather prevented a second attempt to attack Tokyo on February 25th. On March 1, their ships headed south and attacked positions on Okinawa.

The TF 58 carried out new attacks from mid-March to eliminate aircraft and airfields within range of Okinawa. On March 18, carrier-based formations attacked airfields and other military installations on Kyushu and warships in Kobe and Kure the following day, damaging the battleship Yamato and the carrier Amagi . The Japanese hit back with conventional and kamikaze air strikes, lightly damaging three porters on March 18 and severely damaging porter Franklin on the 19th . On March 20, the TF 58 marched south again, but continued to send hunting units against Kyūshū. The Americans reported the Japanese losses on March 18 and 19 with 223 aircraft destroyed in the air and 250 on the ground, while the Japanese reported 161 of 191 aircraft taken off as lost. They did not record any details about machines that were destroyed on the ground. From March 23, the TF 58 attacked Okinawa, but flew new attacks against Kyūshū on March 28 and 29. After the Allied landing on the island on April 1, the TF took over the air defense over Okinawa and flew regular patrols over Kyūshū. In an attempt to stop the large-scale air strikes on the Allied landing fleet, parts of it attacked kamikaze bases on Kyūshū and Shikoku on May 12 and 13 . On May 27, Admiral William F. Halsey took command of the Fifth Fleet from Admiral Raymond A. Spruance . The TF 58, renamed Task Force 38 (TF 38), continued to protect the airspace around Okinawa and repeatedly attacked airfields on Kyūshū on June 2, 3 and 8. On June 10th, she left Japanese waters to freshen up at Leyte in the Philippines.

From July 1, the task force, which now consisted of nine heavy and six light carriers and their escorts, marched back towards the main islands. On July 10, their planes attacked airfields in the Tokyo area and destroyed several enemy planes on the ground. Since they were holding back their air forces for a planned, large-scale kamikaze attack on the Allied fleet, no Japanese planes launched counter-attacks or to intercept the American fighters. After the attack, the TF 38 drove further north and attacked northern Honshu and Hōkkaido on July 14 and 15. Their aviation associations destroyed eight of the twelve railway ferries between the two main islands, along with many other ships. Likewise 70 of the 272 of the small coal freighters that supplied the ferries. 25 Japanese aircraft were destroyed on the ground, interceptors were again not launched. The loss of the railway ferries reduced the coal deliveries from Hōkkaido to Honshu by 80%, which severely hampered production in the factories there. Because of these effects, the operation was later rated as the most effective single strategic air operation of the Pacific War. The battleships and cruisers of the TF 38 also began a series of coastal bombings against industrial facilities on July 14 , which continued until shortly before the end of the war.

After the attacks, the TF 38 marched south again and was reinforced by a large part of the British Pacific Fleet , called Task Force 37 (TF 37) and comprising four carriers . A planned attack against Tokyo on July 17 had to be canceled due to bad weather, but an attack against Yokosuka the next day could damage the battleship Nagato and sink four other warships. On July 24, 25 and 28 , the Allied fleet attacked Kure and the Seto Inland Sea , sinking an aircraft carrier, three battleships, two heavy and one light cruisers, and several other warships. The July 28 attack was supported by 79 USAAF bombers launched from Okinawa. With 126 aircraft shot down, the Allied losses in these attacks were comparatively high. On July 29th and 30th, the carrier associations attacked Maizuru and destroyed three small warships and twelve merchant ships in its port. Following this, the Allied fleet marched east to avoid a typhoon and stash supplies. The next attacks took place on August 9th and 10th and were directed against a concentration of Japanese aircraft in northern Honshu. The Allied intelligence services believed these were in preparation for an attack on the B-29 bases in the Mariana Islands. The naval aviators reported 251 destroyed and 141 damaged enemy aircraft on August 9. On August 13, the TF 38 attacked the Tokyo region again and reported 254 aircraft destroyed on the ground and 18 in the air. The last attack took place on the morning of August 15th. 103 Airmen of the first wave of attacks attacked their targets, but the second wave of attacks was canceled when it became known that the Japanese government had consented to unconditional surrender. Later that day, several Japanese planes attempted to attack the TF 38 but were shot down.

Attacks from Iwo Jima and Okinawa

From March 1945, the USAAF P-51 fighters of the VII Fighter Command stationed on Iwo Jima and used them mainly as escort fighters for their B-29 formations. In addition, they carried out a number of stand-alone ground attacks against targets on the main islands. The first such attack occurred on April 16, when 57 P-51s attacked the Kanoya airfield in southern Kyushu. In further such missions between April 26 and June 22, the P-51 pilots reportedly destroyed 64 enemy machines on the ground and damaged another 180. Ten machines were said to have been shot down in an aerial combat. These numbers were below the expectations of the attackers, which is why they were deemed unsuccessful. VII Fighter Command lost 11 machines to enemy action and another seven for other reasons during the attack missions.

Since the Japanese side hardly launched any interceptors against the American units, the VII Fighter Command only carried out ground attacks from July. These were regularly directed against airfields in order to destroy aircraft that were held back to ward off the Allied invasion. The airfields had anti-aircraft batteries and blocking balloons . At the end of the war, VII Fighter Command had carried out 51 ground attacks, 41 of which were considered a success. The command's pilots claimed 1,062 destroyed aircraft and 254 ships as well as a large number of buildings and rail vehicles . American losses were 157 aircraft and 91 dead.

From May, aircraft of the Fifth and Seventh Air Force , which are combined to form the Far East Air Force (FEAF) , attacked targets on Kyūshū and western Honshu. Their bases were on the conquered Ryūkyū Islands. The attacks represented a phase of preparation for the Allied invasion. From May 17, P-47 Thunderbolts flew regular day and night patrols over Kyūshū to prevent Japanese air traffic there. On June 21st they received support from another fighter squadron and on July 1st from bombers and another fighter squadron. After initially fierce defense attempts, these came to a standstill from the beginning of July, as the Japanese high command withheld its planes for later operations. Between July 1 and July 13, American units flew 286 medium and heavy bombing raids against Kyūshū in which they themselves suffered no losses. Since the fighters rarely encountered Japanese aircraft, they focused their attacks on the country's transport capabilities and other targets that appeared worthwhile. At least twice, there were low-level attacks on groups of civilians.

The attacks on infrastructure and airfields in southern Japan continued until the fighting ceased. By this time, the Fifth Air Force bombers had flown 138 sorties against airfields on Kyushu. The Seventh Air Force flew another 784 sorties. Road and rail bridges have been subject to attacks by both fighters and bombers, and the city of Kagoshima has been the target of regular bombings. On July 31 and August 1, Seventh Air Force B-24s attacked the railroad facilities in Nagasaki Port. While these missions had a more tactical character, the units stationed on Okinawa carried out strategic bombings against industrial plants, including an unsuccessful one on a hydrogenation plant at Ōmuta on August 7th. On August 5th, 10th and 11th there were incendiary attacks by bombers of the Fifth and Seventh Air Force. The FEAF flew their last missions on August 12th, units launched on August 14th were recalled after the Japanese leadership announced that they would accept the Potsdam Declaration. In total, the FEAF flew 6,435 sorties against targets on Kyūshū in July and August and lost 43 aircraft to enemy action.

Reactions in Japan

Air defense

The Japanese air defense was not able to effectively stop the Allied attacks. Due to the short range of the land-based radar systems and the sinking of the Japanese navy's hunting guide ships, the warning time before attacks was no more than an hour. The wiretapping of the Allied radio traffic allowed the early detection of attacks, but not the destination. As a result, the interceptors had only a short time to start the alarm and approach the enemy and mostly only smaller units reached the bomber formations. This was compounded by the fact that many of the fighters could not reach the speed and height of the B-29. From August 1944 it happened that Japanese pilots rammed the enemy bombers to bring them down. From October onwards, several hunting associations specialized in such missions were set up, the pilots of which were supposed to sacrifice themselves. By the end of the war, nine B-29s crashed after ramming and 13 suffered damage. 21 Japanese planes crashed after being rammed. From November 1944, the air defense introduced new cannons with a caliber of 120 mm to its anti-aircraft units, as the 75 and 80 mm guns previously used had turned out to be too weak.

The aerial battles reached their peak in late 1944 and early 1945. As a result of the first B-29 attack on Tokyo, the Navy made a large number of fighters available for air defense and all 120 mm anti-aircraft guns available to date were positioned to protect the capital. Associations deployed to protect industrial centers intercepted regularly approaching bombers between November 24, 1944 and February 25, 1945 and were able to inflict losses on them. As early as the end of 1944, the number of hunters deployed fell noticeably, as unit losses could not be replaced. The poor coordination between the army and the navy still hampered defense efforts in this phase. The Americans suffered few losses in the attacks carried out between March and August 1945.

The defense efforts decreased from April 1945. On April 15, the units deployed for this purpose and the army and navy were combined in the new main air army under the command of Kawabe Masakazu . By this time, the hunting associations had already suffered high losses in combat missions and training flights. The increasingly poor training level of the available pilots and the use of escort fighters on the Allied side meant that the Japanese leadership withdrew their planes from interception missions in order to hold them back for the expected invasion. The progressive collapse of the armaments industry led to a parallel shortage of ammunition in the anti-aircraft batteries. The concentration of these batteries around the industrial centers meant that there was almost no resistance to the attacks on smaller cities. At the end of June the Imperial Headquarters decided to use fighters again against the bomber units. The number of available fighters in the Air Main Army peaked at just over 500 in June and July. In the last few weeks of the war, the B-29 crews had so little contact with the enemy that General LeMay claimed it was safer to engage in combat Flying Japan as a training flight on a B-29 in the United States.

In total, the Japanese air forces were able to shoot down 74 B-29s in aerial combat. 54 crashed due to flak fire and another 19 due to the joint use of flak and fighters. Their own losses were 1,450 in combat and 2,750 otherwise destroyed aircraft.

Treatment of prisoners of war

Most of the aircrews shot down over Japan who survived the crash suffered abuse after their capture. On September 8, 1944, the Koiso cabinet decided that the ruthless air strikes were a form of war crimes . This led to the indictment and, if convicted, the possible execution of captured Allied aircraft crews as war criminals. The regularity of such executions differed in the different military districts. While no executions were carried out in the East (Tōbu) district, which also included Tokyo, these occasionally occurred after brief trials in Tōkai , Chūbu and West (Seibu, ie Chūgoku , Shikoku , Kyushu ). Sometimes members of the Kempeitai executed groups of prisoners. Angry civilians occasionally killed fallen allies before the military could advance and capture them. The Kempeitai often used brutal methods to interrogate prisoners.

Of the approximately 545 Allied military personnel who crashed and were captured over the main Japanese islands (excluding the Kuriles and Ogasawara Islands ), 132 were executed and a further 29 were killed by civilians. 94 died of other reasons in Japanese prisons, including 52 incarcerated in Tokyo when the Americans bombed the city on May 25-26. Six or eight Americans shot down on May 5th were subjected to vivisections by Ishiyama Fukujirō and supporting doctors on a total of four different days at Kyūshū University . The responsible military authorities were informed about the events and had participated in their planning. Many of those responsible for the deaths of prisoners were indicted in the Yokohama war crimes trials after the war . Some of the convictions were followed by executions, and the remaining convicts received prison terms.

Atomic bombs and final attacks

From 1942 onwards, the United States, supported by Great Britain and other allied nations, began the development of nuclear weapons in the Manhattan Project . In December 1944, the USAAF set up the 509th Composite Group under the command of Colonel Paul Tibbets , which, after the production of operational nuclear weapons, was to drop them over the specified targets. In May and June 1945 the group moved to Tinian. The Manhattan Project led to the successful Trinity test on July 16 of that year . Four days later, the specially retrofitted B-29s of the 509th Composite Group began training missions against Japanese cities, with each bomber carrying a Pumpkin bomb weighing more than five tons . There were no encounters with Japanese fighters during the training flights. In the meantime, US President Harry S. Truman approved the use of nuclear weapons against Japanese cities on July 24. The following day, General Spaatz received the relevant orders that August 3 was the day of the first drop and Hiroshima , Kokura , Niigata and Nagasaki were possible targets. Kyōto , Japan's former capital, was listed in an earlier version of the order under the goals, but was replaced by Nagasaki by order of Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson , which gave Kyōto a high cultural value. The city had been excluded from the fire bombing raids for the same reasons. On July 26th, the United States, Great Britain, and the Republic of China announced the Potsdam Declaration calling for Japan's unconditional surrender as the alternative was immediate and unconditional annihilation. On July 28th, the Japanese government rejected all demands of the declaration.

At 8:15 a.m. on August 6, the B-29 Enola Gay, flown by Colonel Tibbets, dropped the Little Boy nuclear weapon over central Hiroshima. The explosion that followed killed tens of thousands of people and destroyed 12 km² of urban area. The bomber and its crew of six returned safely to the Mariana Islands after the attack. Post-war estimates assume that 66,000 to 80,000 people were killed immediately and between 69,000 and 151,000 injured in the explosion. Tens of thousands of people died, some years later, of injuries and radiation sickness . Estimates suggest that by the end of 1945 a total of around 140,000 people had lost their lives to the bomb. Estimates of the total deaths caused by this speak of up to 230,000 deaths. 171,000 of the survivors were considered homeless after the explosion.

Following the attack, President Truman made a radio address announcement that the United States had used an atomic bomb on Hiroshima and would continue air strikes against industrial and transportation facilities. The address also contained the threat that if Japan did not accept the Potsdam Declaration, a rain of destruction would fall on the country such as the world has never seen. Daytime incendiary bombing attacks on Yawata and Fukuyama two days later destroyed 21% and 73% of the cities respectively. The formation flying against Yawata was intercepted by Japanese fighters and lost one B-29 and five P-47s, the Japanese lost an estimated 12 aircraft.

The second nuclear weapons drop took place on August 9th. The B-29, known as Bockscar , took off to drop Fat Man , a plutonium bomb (the bomb dropped on Hiroshima used U 235 ) on Kokura. Since the city was covered extensively by mist and smoke, the pilot Charles Sweeney decided to fly to the secondary destination Nagasaki. At 10:58 a.m., the crew dropped Fat Man over the city. The explosion, with an explosive force of 20 kilotons of TNT equivalent, destroyed 3.8 km² of urban area in the Urakami district . Japanese statistics published in the late 1990s believe that more than 100,000 people were killed as a result of the explosion. The attack also hit the industrial facilities in the city hard. Steel production fell out for a year, the power supply struggled with severe bottlenecks for two months, and the armaments industry also suffered severe cuts. Since it had used too much fuel when approaching the alternative target, the Bockscar landed on the much closer Okinawa instead of Tinian. The Soviet invasion of Manchuria also began on August 9th , during which the Red Army gained enormous territorial gains within a short period of time. B-29 also dropped 3 million leaflets over Japanese cities announcing that the Allies would use atomic bombs to destroy the country's military resources until the Tennō ended the war. At that time, it was assumed on the American side that a third bomb would be ready for use by the end of August. By the end of November, eight bombs were expected to have been completed and Chief of Staff of the Army George C. Marshall advocated keeping them in reserve so that they could be used against tactical targets in the planned Allied invasion.

In response to the atomic bombing and the Soviet entry into the war, the Japanese government began negotiations with the Allies on the terms of surrender on August 10. During this time, the number of bombing attacks was reduced and only one attack on oil facilities from August 9th to 10th and one on a factory in Tokyo on the 10th by the 315th Bombardment Wing. The next day, President Truman ordered the attacks to be suspended, as these could otherwise be interpreted as a sign that the Allies viewed the negotiations as a failure. On the same day, General Spaatz announced a new target directive that shifted the target priority from cities to the transport infrastructure in the event that the attacks were resumed. On August 13, B-29s dropped copies of the terms of surrender submitted to the Japanese government over various cities in the country. When the negotiations seemed to stall, General Spaatz was ordered to continue the bombing. General Arnold wished in this the largest possible attack and expressed his hope that the USASTAF would be able to send 1,000 aircraft against the Tokyo area and other places in the country. A total of 828 B-29s and 186 escort fighters, a total of 1,044 aircraft, flew daylight attacks against Iwakuni, Osaka and Tokoyama and night incendiary bombs against Isesaki and Kumagaya that day . General Doolittle decided not to send airmen from his Okinawa-based Eighth Air Force to support these attacks, even though the Eighth Air Force had not yet flown a single operation against the main islands. He justified this by saying that he did not want to risk the lives of his crews when the war was practically over. These were the last air strikes of the war by heavy bombers against Japan and on the afternoon of August 15, Tennō Hirohito announced in a radio address Japan's intention to surrender and announced the end of the fighting.

After the fighting stopped and the war ended

In the weeks following the adoption of the Potsdam Declaration on August 15, further missions were flown to a limited extent, with occasional incidents. On August 17 and 18, fighters of the Japanese Navy attacked Consolidated B-32 near Tokyo , which were conducting reconnaissance flights over Japan from Okinawa. On August 17, the Twentieth Air Force received an order to air-supply Japanese prisoner-of-war camps in Japan, Korea and China until the prisoners could be evacuated. The drops began ten days later and by September 20, the B-29 had dropped a little under 4,500 tons of relief supplies in almost 1,000 missions. Eight bombers crashed during the operations and one was damaged over Korea when it was attacked by a Soviet fighter plane. General Spaatz ordered that bombers and fighter planes should repeatedly fly over the Tokyo metropolitan area from August 19 until Japan's formal surrender. Bad weather and logistics problems meant that the first such proof of strength could not be carried out until August 30, when the patrol flights took place parallel to the landing of Douglas MacArthur and the 11th US Airborne Division on the Atsugi airfield. A similar patrol took place the following day, and on September 2, 462 B-29s and many carrier-based aircraft flew over the Allied fleet in Tokyo Bay after the official signing of the surrender.