Operation Downfall

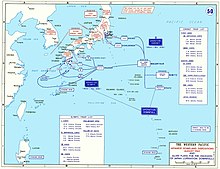

The Operation Downfall was the Allied plan for the invasion of the main islands of Japan at the end of the Pacific War in World War II .

The plan was divided into two parts, Operation Olympic , which included the invasion of Kyūshū in November 1945, and Operation Coronet , which included the invasion of Honshū near Tokyo in the spring of 1946. However, after the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Soviet Union entered the war against Japan, the Japanese capitulated before the plans were implemented.

planning

The USA was responsible for the planning of operations. Since at that time the development of the atom bomb within the Manhattan Project was still a closely guarded secret and only very few in management circles were privy to it, it played no role in the planning.

For an invasion of Japan, a joint command had to be formed from the previously divided Pacific commands. After some competence wrangling between the various management levels of the different branches of arms, an agreement was reached on US General Douglas MacArthur .

As early as 1943, the commanders in chief of the American armed forces agreed that the Japanese should surrender no later than a year after the Germans . They were strengthened in this when British plans emerged that would not take the Japanese homeland before the spring of 1947. The Americans saw the morale of their own people in danger through such a prolonged war .

Japan itself offered many scenic opportunities for landing troops. The most suitable beaches were on the southern island of Kyushu and the Kanto Plain, southwest and southeast of Tokyo . Therefore, a two-step invasion was decided. With the operation Olympic should first Kyushu be taken so that there military airfields were built. With these it would have been possible to provide increased air support to the following Operation Coronet in Tokyo Bay.

The preparation also included spying on the Japanese units that were ready to defend the motherland. Based on intelligence reports obtained in early 1945, the predictions were as follows:

- Not only will the Japanese military oppose the invasion, but also a fanatical, hostile civilian population.

- At the start of Operation Olympic three enemy divisions will be stationed in southern Kyushu and another three in the north of the island.

- The total enemy force against Operation Olympic will not exceed eight to ten divisions. However, this number can be reached quickly.

- At the start of the invasion, 21 enemy divisions will be stationed on Honshū, 14 of them in the Kanto plain alone.

- The Japanese will most likely move their land-based air force to mainland Asia to protect them from American attacks. Under these circumstances it is possible that a fleet of 2,000 to 2,500 combat aircraft can be built up in a steadily producing industry and that this will also be used against the landing forces in the planned invasion of Kyushu. Local airports can be used as intermediate bases.

Operation Olympic

Operation Olympic was scheduled to start on November 1, 1945 (X-Day). The Allied force for the landings was the largest ever assembled. It consisted of 42 aircraft carriers , 24 battleships and about 400 destroyers with their escort ships. 14 US divisions were planned for the landings themselves. Okinawa was ready as an intermediate base from where the southern part of Kyushu was to be taken. There was also a misleading plan, Operation Pastel , which was supposed to simulate an Allied attack on the ports of China .

Five days before the main invasion, the capture of the islands of Tanegashima , Yakushima and the Koshiki island chain was planned. This resulted from the positive experience of the Battle of Okinawa , where anchorages for ships that were no longer needed on the landing beaches or for damaged ships were available.

General Walter Krueger's 6th US Army was to land on Kyushu at three points: at Miyazaki , Ariake (today: Shibushi ), and Kushikino (today: Ichiki-Kushikino ). The 35 beaches were codenamed according to car brands - from Austin , Buick , Cadillac , to Stutz , Winton , and Zephyr .

The planners assumed that the Americans would be 3: 1 superior to the Japanese if a corps went ashore at each landing point. In the spring of 1945, Ariake and the port next to it was the only heavily guarded point of all landing points. The units at all other points should therefore have little difficulty penetrating inland.

However, the invasion was not designed to conquer the entire island, but only the southern third. From there it was planned to support Operation Coronet with expanded bases , especially with airports for the US Army Air Forces .

Operation Coronet

Operation Coronet was scheduled to start on March 1, 1946 (Y-Day). The hitherto largest amphibious operation of all time was to take place on Honshū in the plain of the capital Tokyo. For this purpose, the use of 25 divisions was planned. The 1st US Army (General Courtney H. Hodges ) was assigned to the Kujukuri beach on the Bōsō Peninsula , while the 8th US Army ( LtGen Robert L. Eichelberger ) was supposed to start the invasion of Hiratsuka in Sagami Bay . Then both armies were to advance north inland and then unite in Tokyo .

The Japanese Defense Plan "Ketsu-gō"

Meanwhile, the Japanese were working out their own plan, expecting an invasion as early as the summer of 1945. But since the Battle of Okinawa dragged on longer than expected, they assumed that the Americans would not be able to start another operation before typhoon season. The weather would then have become too risky for an amphibious operation.

Since the Japanese no longer saw a realistic chance of winning the war, they counted on defending the motherland with such strength that the Americans would only be able to conquer them with intolerable losses. This was ultimately aimed at a possible ceasefire .

The Japanese plan for averting the invasion was called Operation Ketsu-gō ( 決 号 作 戦 , Ketsu-gō sakusen ), in German about "Operation Decision".

Kamikaze insert

The Japanese defense paid special attention to the use of Kamikaze aircraft. Since even the training pilots of the fighter planes and bombers were assigned to the mission, the Japanese now put quantity against quality. The army and naval forces had more than 10,000 machines operational by July, and by October it should be significantly more. The Japanese planned to use all aircraft that could reach the invading fleet.

In the Battle of Okinawa, the kamikaze pilots managed to achieve a hit ratio of 9: 1, that is, every ninth attack was a hit. In Kyushu they hoped the better circumstances would give them a 6: 1 ratio. Therefore, it was expected that the machines would sink more than 400 ships. Because the pilots were also trained to recognize transporters , in addition to aircraft carriers and destroyers, the Allied losses should be disproportionately higher than on Okinawa. A study by the command staff even spoke of the possible destruction of a third or even half of the invasion fleet.

Naval forces

Due to the very high losses in the sea and air battles in the Gulf of Leyte and the air raids on their naval bases , the Japanese hardly had any larger ship units than destroyers. In August around 100 medium-sized Koryu-class submarines and around 250 of the slightly smaller Kairyu- class were completed. There were also 800 Shin'yō Kamikaze boats of the army.

Ground troops

To counter an amphibious landing operation, the defender has two options: a strong defense of the beaches or a defense from the depths. In an earlier phase of the war, for example on Tarawa in 1943 , the Japanese tried to defend the beaches with a strong force, with almost no reserve units being able to be deployed. This tactic, however, proved to be very fragile in the face of the coastal bombing that preceded an invasion. Therefore, the Japanese later preferred the other strategy on Peleliu , Iwo Jima and Okinawa and dug their units into the more defensible terrain of the hinterland. This led to long, grueling battles with high American losses, but ultimately with no prospect of success for the Japanese.

The Japanese used mixed tactics to defend Kyushu. The main forces lay a few miles inland behind the beaches to avoid bombardment, but close enough not to allow the Allies a chance to build a beachhead before they met the defenders. The counterattack units were always ready to intervene further inland in order to be able to advance to the most contested beach.

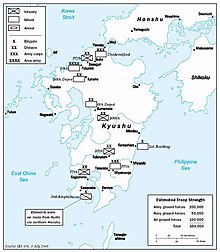

In March 1945 there was only one division in Kyushu. Over the next four months, the Japanese withdrew more units from Manchukuo , Korea, and northern Japan and brought them to Kyushu. In August the total troop strength there amounted to around 900,000 soldiers. There were 14 divisions and smaller troop units there, as well as three tank brigades.

Although the Japanese were able to recruit many new soldiers, there was a lack of equipment for the troops. In August there were 65 divisions all over Japan, but the equipment was only sufficient for about 40 and the ammunition only for 30. The Japanese did not bet everything on the outcome of the Battle of Kyushu, but their main efforts were so focused that that hardly any reserves remained. The troops on Kyushu owned around 40 percent of all ammunition reserves.

In addition, the Japanese had called on all civilians to organize themselves in patriotic combat corps in order to provide support and also to carry out combat missions themselves. There was a general lack of weapons and training, but it was expected that everyone would fight the invasion with all their might.

More recent Allied estimates for Operation Olympic

In the summer of 1945, the US secret service continued its efforts to estimate the defenses of the Japanese on Kyushu as precisely as possible.

Air defense

An attack on the landing fleet while at sea would be much easier for the Japanese than it was on Okinawa, where their planes had to travel a long way across the sea. They could fly overland to defend Kyushu and only needed a short distance over water to the ships. In addition, it became clear that the Japanese subordinated almost all of their warplanes to the Kamikaze company. In an August report, the army assumed there were up to 5,911 aircraft. The US Navy , which made no distinction between training and combat aircraft, estimated the number for August at over 10,000.

So the Allies prepared their aircraft carriers to take more fighters on board and to exchange the torpedo and dive bombers against them. In addition, B-17 bombers were to be converted into radar aircraft; Predecessor of today's AWACS machines.

Admiral Nimitz drafted a plan to simulate an invasion a few weeks before Olympic, in which a fleet of ships equipped with anti-aircraft guns from bow to stern should approach the island. If the Japanese ran into these ships with their kamikaze planes, which were only fueled for the one-way flight, they would lose much of their air support for the later invasion.

Ground defense

From April to June, the US secret service followed the armament of Kyushu, which also included five divisions being relocated to the island. Based on these observations, as well as eavesdropping and deciphering Japanese military radio communications, the Americans estimated that around 350,000 soldiers would be stationed on Kyushu by November. This changed rapidly in August, when four new divisions were discovered in one fell swoop and signs of further transfers and recruiting were made out. In August the number was 600,000 soldiers, more than three times previous expectations.

This rapid Japanese rearmament led General Marshall in particular to demand drastic measures with regard to Operation Olympic. He even went so far as to suggest devising an entirely new plan.

Use of chemical weapons

The predictable wind directions made Japan vulnerable to gas attacks . Such attacks would severely limit the Japanese ability to fight out of caves.

The Geneva Protocol of 1925 expressly excluded the use of chemical warfare agents , but neither the United States nor Japan had signed it. Although the Americans had promised not to use chemical weapons at the beginning of the Pacific War, the Japanese had already used gas against China in Manchuria ( Unit 731 ). This provided the US with an argument in favor of using chemical weapons.

Use of nuclear weapons

At the behest of General Marshall, Major General John E. Hull dealt with the tactical use of nuclear weapons . He reported that seven bombs would be available on X-Day to be used against the Japanese defenders. Colonel Seeman then interjected that his own troops could only enter an area hit by an atomic bomb after 48 hours; the risk of fallout and the actual explosive power of the nuclear bomb was not clear to the military at the time, as not even the scientists of the Manhattan Project could make precise statements about it.

Alternative destinations

Due to the high and increasing concentration of Japanese troops on Kyushu, the American command staff began to consider an alternative plan that included the invasion of Shikoku Island and northern Honshū near Sendai or Ōminato (today: Mutsu ). A direct landing in Tokyo Bay was also discussed, as there were far fewer defense troops in North Honshu. However, this would have meant the task of air support by land-based aircraft, except for the B-29 , from Okinawa.

Expected casualty numbers for "Downfall"

Since the Japanese expected a self-sacrificing defensive behavior that did not spare their own lives and the high defensive strength was known, high casualties were seen as inevitable. No one could predict exactly how high they would be. Many estimates existed, but their numbers varied widely. On the one hand, they served to weigh up the pros and cons of an invasion and were later used to justify the US decision to use the atomic bomb .

Examples:

- Assessment by the General Staff in April 1945:

- 456,000 casualties, including 109,000 deaths over a 90-day period for Operation Olympic.

- After a further 90 days and the completion of Operation Coronet, a total of 1.2 million victims, including 267,000 dead.

- Study commissioned by Admiral Nimitz in May 1945:

- 49,000 victims in the first 30 days, including 5,000 at sea.

- Study commissioned by General MacArthur in June 1945:

- 23,000 victims in the first 30 days and 125,000 after 120 days. These numbers were revised down to 105,000 at a meeting to take account of wounded soldiers who might later return to service.

- At a conference with President Truman on June 18, the numbers ranged from 31,000 to 70,000 victims after 30 days.

- Study by William B. Shockley on the conquest of the Japanese islands:

- 1.7 to 4 million victims, including 400,000 to 800,000 allies dead. Japanese casualties were estimated at up to 10 million, assuming strong civil defense.

See also

literature

- Christopher Chant: The Encyclopedia of Codenames of World War II. Routledge Kegan & Paul, 1987, ISBN 978-0-7102-0718-0 (English, codenames.info [accessed July 28, 2020]).

- Thomas B. Allen , Norman Polmar : Code-Name Downfall . Simon & Schuster, New York 1995. ISBN 0-684-80406-9 .

- Richard B. Frank : Downfall. The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire . Random House, New York 1999. ISBN 0-679-41424-X (hc), ISBN 0-14-100146-1 (2001 tpb).

- John Ray Skates : The Invasion of Japan: Alternative to the Bomb . University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, SC 1994. ISBN 0-87249-972-3 .

Web links

- Original document of Operation Downfall (English, PDF file)