Korea under Japanese rule

| Chosen Province era | |

|---|---|

| Japanese name of the era | |

| Kanji | 日本 統治 時代 の 朝鮮 |

| Hepburn | Nippon Tōchi-jidai no Chōsen |

| translation | Korea at the time of Japanese rule |

| Korean name of the era | |

| Hangeul | 일제 시대 |

| Hanja | 日 帝 時代 |

| RR | IIlje Sidae |

| MR | Ilche Shidae |

| translation | Period at the time of the Japanese Empire |

At the beginning of the 20th century, Korea came under Japanese rule . In 1905 Korea became a Japanese protectorate and in 1910 it was completely incorporated into the Japanese Empire as a Japanese colony with the name Chosen by annexation . The colonial rule over the Korean Peninsula officially ended with the surrender of Japan on September 2, 1945, but in fact only completely with the handover of the province to the American victorious power on September 9, 1945 or de jure with the establishment of the Republic of Korea on August 15, 1948. North Korea ( Democratic People's Republic of Korea ) is not recognized by Japan, but South Korea (Republic of Korea) as the representative for all of Korea. Therefore, the repeal of the annexation treaty is “interpreted” by the colonial power at that time.

With the surrender of Japan in the emerging Cold War , Korea came between the interests of the United States and the Soviet Union, and later the People's Republic of China . This led to the establishment of two warring successor states - North and South Korea - and the Korean War .

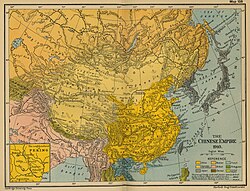

Geography of Chōsen

The administrative unit of Chosens essentially corresponded to the incorporated Korea, i.e. the Korean Peninsula and its offshore islands. Only the administrative sovereignty of the Takeshima archipelago was assigned to the new colony by the Shimane Prefecture .

Administrative division of Chōsen

The administrative system of Greater Korea was adopted. The names were also adopted, with the Chinese characters no longer being read in Korean but in Japanese . This also applied to places and squares. The provinces of the former Korea were therefore pronounced as follows:

| Korean name before 1910 | Japanese name after 1910 | Kanji |

|---|---|---|

| Chungcheongbuk-do | Chūsei-hokudō | 忠清北道 |

| Chungcheongnam-do | Chūsei-nandō | 忠 清 南 道 |

| Gangwon-do | Kōgen-do | 江原道 |

| Gyeonggi-do | Keiki-do | 京畿 道 |

| Gyeongsangbuk-do | Keishō-hokudō | 慶 尚 北 道 |

| Gyeongsangnam-do | Keishō-nandō | 慶 尚 南 道 |

| Hamgyeongbuk-do | Kankyō-hokudō | 咸 鏡 北 道 |

| Hamgyeongnam-do | Kankyō-nandō | 咸 鏡 南 道 |

| Hwanghae-do | Kōkai-do | 黄海 道 |

| Jeollabuk-do | Zenra-hokudō | 全 羅 北 道 |

| Jeollanam-do | Zenra-nandō | 全羅南道 |

| Pyeonganbuk-do | Heian-hokudō | 平安 北 道 |

| Pyeongannam-do | Heian-nandō | 平 安南 道 |

Prehistory up to the annexation of Korea

|

History of Korea from the 10th century |

|---|

| States of imperial unity |

|

| Colonial times |

|

| Division of Korea |

|

Korea under the hegemony of other great powers

After the forced opening of the Japanese ports by US ships and the implementation of the first steps of the Meiji reforms , efforts were made in Japan to want to incorporate Korea : They wanted to "found an empire like the European countries" and have colonies in order to become equal and not to become dependent yourself ( Inoue Kaoru ). At that time, Korea was an autonomous , tributary vassal state of the Chinese Empire under the Qing Dynasty . However, it was an advantage for Japan that Korea was relatively weak and isolated at the time. In addition, Korea offered a strategically ideal starting point for further expansion into China and Russia .

In 1876 Japan forced the Japanese-Korean friendship treaty by sending warships : the "Hermit Kingdom" of Korea was opened to the Japanese economy and diplomatic relations between the two countries were established. The rapidly growing imports of goods and technologies according to trade agreements with the Empire of China and Western powers opened up new influence in Korea in particular for Russia and Germany.

The social conditions in Korea of the Joseon Dynasty , which were marked by corruption and oppression , led to the Donghak uprising in 1894 , against which Chinese help was called. According to the Treaty of Tientsin of 1885, the Chinese intervention gave Japan the right to intervene, which it made use of by sending its own intervention troops. Since both sides strove for hegemony over Korea and neither side was ready to be the first to withdraw their troops after the uprising was temporarily over, the tensions culminated in the First Sino-Japanese War . After the defeat for the Chinese Empire in 1895, the Shimonoseki Peace Treaty followed , in which it recognized the “full and comprehensive sovereignty and autonomy of Korea” and thus lost its protectorate status and much of its influence over Korea.

Western reforms were carried out under Japanese influence. Examples of these were the abolition of the Confucian state examinations for civil servants and the introduction of German civil law, which had already been carried out in Japan . In 1894, Japanese forces occupied the royal palace in Hanseong as part of the Donghak uprising . Since the then Queen Myeongseong was hostile to Japanese politics, she was murdered by Japanese and Korean assassins a year later on October 8, 1895. On February 11, 1896, King Gojong , his new wife, Princess Eom Sunheon , and Crown Prince Sunjong sought refuge in the Russian embassy. They left these again in 1897 with the proclamation of an empire of Greater Korea , which officially ended the Joseon dynasty.

After the First Sino-Japanese War, Japan had to give the strategically valuable Liaodong Peninsula off Korea back to China. This happened due to international pressure in Shimonoseki's intervention . China leased the peninsula to Russia, which wanted to build an ice-free naval port in Port Arthur . Japan saw this as a threat to its sphere of interest. Tensions increased as Russia sought hegemony over the Korean Peninsula and deployed troops in Manchuria . As a result, the Russo-Japanese War was waged in 1904/05 . On September 5, 1905, the defeated Russia accepted Korea as a Japanese area of interest in the Portsmouth Peace Treaty .

Korea as a Japanese protectorate

As a result, the Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty of 1905 was signed in Hanseong on November 17, 1905 , making Korea a Japanese protectorate and losing its sovereignty.

The post of General President was created for the central administration and external representation of Korea; he was head of the protectorate and representative of the Japanese government. Itō Hirobumi held this office from 1905 to 1909 . As general resident, he also took on internal and military administration. Under the protectorate administration, Japanese officials took over administration and courts and introduced Japanese administrative rules. The police and the penal system were also Japaneseized, and the Korean army was disarmed and disbanded. In June 1910, the Japanese military police received a commander-in-chief who was also given supervision over the civilian police.

Nonetheless, violent resistance against Japanese rule also formed, starting in particular from the Confucian schools and youth groups. A partisan army was formed, albeit poorly armed, which, in addition to attacks on railways and telegraph stations, also involved the Japanese colonial army in combat. Ultimately, however, the partisans had to move to Gando north of the Yalu (in 1908, there were 21,000 Chinese and 83,000 Koreans living in this disputed area between China and Korea), where they resisted until 1915.

Annexation of Korea as a Japanese province

After the important for Japan politician Itō Hirobumi was murdered on October 26, 1909 on a trip to Manchuria in Harbin by the Korean independence fighter An Chung-gun , the Japanese government forced the signing of the annexation treaty on August 22, 1910 and thus the incorporation of Korea as a new province of Japan.

The Korean Emperor Sunjong , who had meanwhile replaced Emperor Gojong from his throne, ceded all sovereign rights of Korea to the Japanese Emperor in this treaty . As contractually guaranteed, he was given the title of king, albeit without operational and administrative rights. The rest of the Korean ruling family was also integrated into the Japanese imperial family with "mutual succession rights" including the marriage of the future Crown Prince Yi Eun to the Japanese princess Nashimoto-no-Miya Masako .

The governor general , who replaced the general resident in his function and adapting to the newly created foreign policy realities, was also formally installed as supreme commander and in this way the whole of Korea became visible as a Japanese province under the name Chōsen ( Japanese 朝鮮 ; kor. 조선 , Joseon ) annexed , which extinguished Korea's international legal capacity. The people of Chōsen accepted the contract when it was signed and when it was proclaimed on August 29, 1910 without any kind of rejection.

Japan gave the impression that, after a state union since 1910 , Korea had been an integral part of the Japanese Empire and accordingly had equal rights. However, only one person of Korean origin was a member of the Japanese mansion (1944), and in the same year a single person of Korean origin became a member of the House of Representatives . A total of 54 people of Korean origin belonged to the administration of the governor general in Chosen.

Colonial times

Society and culture

The total population of Chōsen at the beginning of the incorporation was about 9,670,000. The presence of non-Korean residents increased steadily between 1906 and 1935:

- 1906: 39,000

- 1910: 171.543

- 1920: 346,000

- 1925: 424.700

- 1930: 527.016

- 1935: 619,000

Most of these people came from other parts of the Japanese Empire, many of them from the main Japanese islands.

Not all of the rights that the Japanese of Japanese descent were granted have also been granted to the Japanese of Korean descent since 1910. This included, among other things, the right to assembly and organization, freedom of speech and an independent press: all Korean newspapers and magazines had to cease publication in 1910, leaving one Korean-language one, English and a few Japanese newspapers, which were published by the provincial government under censorship.

With the incorporation into the Japanese Empire, the state Shinto was introduced as the state religion . Daily participation in the temple rituals became compulsory from 1925, especially for schoolchildren and students. The then Governor General Saitō Makoto knew about the problems involved in intervening on such a fundamental basis. He therefore stated that the visit to the Shinto shrines does not serve to adopt this religion, but the shrines are dedicated to the ancestors and the visit therefore represents a patriotic act. From 1935, the pressure to participate increased, so that some Christian schools themselves closed in protest. The Korean parents, on the other hand, had considerable concerns and resistance to such protest measures, as they wanted to give their children the opportunity to have a “good education”. As a result of this rejection by the parents, Saito's declaration was now also accepted by Christian schools in 1937, and teaching continued with it. In addition, the Chinese calendar was replaced by the Gregorian calendar common in the western world . The Japanese language became the national language and from 1915 the sole language of instruction.

From 1886, still under the Joseon dynasty , girls' schools were established - partly at the instigation of foreign Christian missionaries - in which female students enjoyed Western education. For this purpose, the Chanyanghoe Society ( 讚揚 會 ) was formed in 1898 . However, the Japanese rule enabled a further softening of previously comparatively rigid social structures, in particular a change in gender roles : The Japanese school system with its educational content was introduced, which now made education possible for the entire population of Chōsen, and not only, as in the past, for the aristocratic upper class. Today's Ewha Womans University , which emerged from a girls' school, offered college courses. Women earned their own income and were more easily able to advance socially through education and work than under the Joseon dynasty. The Maeilsinbo newspaper published statistics in its July 21, 1931 edition, according to which there were 9779 male 3337 female industrial workers in the capital city prefecture, who were particularly numerous among the younger generation. The first organizations of working women were founded in the 1920s, some of which were very popular.

After the death of the penultimate King Gojong in January 1919, anti-Japanese unrest broke out across the country , culminating in the declaration of independence by the March 1 , 1919 movement . Immediately after the proclamation of independence, the uprising was bloodily suppressed, officially 553 people were killed and 185 injured. As a result of the suppressed protests , a Korean government-in-exile was founded almost immediately afterwards, on April 10, 1919, in Shanghai with the help of Rhee Syng-man and Kim Gu . The incident had no impact at international level.

Nevertheless, the provincial government achieved a moderation of the colonial policy : In August, Admiral Saitō Makoto, a new governor-general was appointed, his second colleague was a civilian. Saitō spoke out for the protection of Korean culture and customs, he also promoted the welfare and wanted to serve the happiness of the people of Chōsen. The Korean language was temporarily allowed again as the language of instruction and some residents of Chosens of Korean origin were involved in the administration of the new governor-general. Although the police were then increased by 10,000, the Japanese military police, which had been keeping order up to that point, were replaced by civilian police. The press area was also affected by the relief. In the course of the twenties, the number of Korean-language newspapers increased to five, including the daily newspapers Tōa Nippō (dt. "East Asian daily newspaper") and Chosen Nippo (dt. "Korean daily newspaper"), founded in Keijō in 1920 . In the first half of the 1920s the first women's magazine called Yeojagye came onto the market, followed by modern women's magazines based on Japanese models in the 1930s. B. Yeoseong of the editor of Chosun Ilbo.

The Governor General's residence was built in 1926 on the site of the Keifukyū Royal Palace, which had previously been partially demolished . This rose on the line of sight palace - city. South Korea demolished the building used by the provincial government for the parliament and the national museum exactly fifty years after Japan's surrender in World War II on August 15, 1995. On the grounds of the Shōkeikyū Royal Palace , the Japanese provincial government established a zoo, a botanical garden (the so-called Shōkei Park ) and a museum. The South Korean government had the zoo and botanical garden removed in 1983.

Nevertheless there were protests again and again. B. also on October 30, 1929 in Kōshū : As the climax of some class boycotts, Korean students took to the streets to demonstrate for the reintroduction of teaching Korean history and the reintroduction of the Korean language as the language of instruction. The protest was Chosen-wide cause for other students to also demonstrate. The protests and class boycotts were initiated by student organizations. Without reaching their goal, the student protests collapsed mainly due to internal disputes.

Many of the abovementioned easements were reversed with the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 and the subsequent Second World War , and the old regulations were partially reinforced. The local government under the governor-general Minami Jirō also tried to introduce the Japanese culture and way of thinking in Chōsen. The policy of total assimilation carried out under the slogan Nae-son-il-chae (“Nae” = inside, Japan; “son” = Korea of Chosŏn; “Il” = one; “Chae” = body) should be the one for the since the attack on Pearl Harbor wars waged on several fronts to secure the resources required, especially in terms of people for the military and industry. In a speech from 1939, Governor General Minami explained the slogan "Nae-son-il-chae" as follows: "Korea and Japan must become one in form, in spirit, in blood and in flesh"; Ultimately, the goal would be complete equality between Koreans and Japanese, and any discrimination, including in the military, would be abolished. On the other hand, as can be seen from a speech in Tokyo in 1942, Minami knew of the difficulties involved in carrying it out: “The Koreans are a completely different people when it comes to worldview, humanity, customs and language. The Japanese government must therefore draft its colonial policy with full awareness of this fact. ”This was based on the conviction“ that the Japanese, to whom the Koreans always have to look up, must always be a few steps ahead. Because the Japanese are called to always teach and lead the Koreans, and they should follow the advancing Japanese with gratitude and obedience. ”This policy was expressed in everyday life in Chōsen as follows: From 1938 the Korean language was also used in private Space forbidden and secured by a spy even in the family area. The earlier Korean culture suffered as well; as an example, the Korean costume was banned.

From February 1940 attempts were made to convert Korean names into Japanese or to translate them; the project, which was scheduled to last only six months, only achieved the frugal success of 7.6% Koreans registered with Japanese names by the end of April 1940. When grocery cards, mail deliveries, job assignments, and government applications were only given to people with Japanese names, many gave in. In August 1940, 79.3% of the population were registered with Japanese names.

Due to the courteous surrender of Japan in World War II and the almost immediate spin-off of Chōsen from the Japanese Empire, the Nae-son-il-chae policy could never be fully carried out and thus no equality between the Japanese and Korean-born residents could be created . Until the end of the Japanese colonial rule, the ban on marriages between these two population groups was never lifted.

economy

Japanese dominance

In the Japanese-Korean friendship treaty of 1876 Japan had imposed the same foreign trade conditions on Korea as Japan in the American-Japanese friendship and trade treaty of 1858: exchange of diplomats , the opening of three ports for trade, the possibility of Japanese citizens in these ports were allowed to act and live, the guarantee that these people would remain under Japanese jurisdiction and minimized import duties for Japanese goods. However, Japan had recognized Korea's independence from China.

In 1905, with the Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty , Korea transferred all of its foreign trade to Japan, and in 1910, when it was incorporated into the Japanese Empire, it also transferred domestic trade.

Most of the time, companies with an owner of Japanese origin were preferred in order distribution. A year later, 110 companies in trade and industry were active or founded in Chōsen, but 101 of them were owned by Japanese roots. There were also 19 companies of Japanese origin with branches in Chōsen. This one-sided relationship was reinforced by the closure of two larger and more successful Korean-born companies, the Korean Land and Maritime Transportation Company and the Korea Hide Company , and the nationalization (and subsequent modernization) of ginseng production and mines .

Objectives of the development program

Internal trade in Korea was very poorly developed. Japan therefore built the economy in Chōsen from scratch and purposefully: the south of the peninsula was not very suitable for generating energy and resources , so that the development of industry was more concentrated in the north and agriculture was promoted in the climatically favored south.

The construction of Chōsen should primarily serve the military and the prosperity of the population on the main Japanese islands. The expansion of agriculture in southern Chosen as a new "granary" should also help to further industrialize the other regions of the Japanese Empire and to overcome the agricultural structure with 80% of the rural population.

The regional imbalance in the economic structure in Chosen led to a south-north migration within the province on the one hand and to the emigration of people from the southern area of the province to the Chinese Empire , Hawaii and the other parts of the Japanese Empire on the other.

Railway lines (and roads) were built to develop the whole country. The infrastructure built up at this time played an important role in Chōsen's economic development. This also applies to the two successor states, especially North Korea, as long as the infrastructure was not destroyed during the Korean War (1950–1953).

Agriculture

From 1912 the Japanese provincial government increasingly expropriated small farmers in particular. This initially took place in favor of the "Eastern Real Estate Corporation" through new measurements and soil inspections of the agriculturally usable soil. All land with insecure property relations fell to this company, which was founded in the first years after the annexation, and was passed on to immigrants of Japanese descent and pro-Japanese provincial residents of Korean descent. In 1916, 36.8%, 1920 39.8% and 1932 52.7% of the arable land in Chosen Province were recorded as belonging to Japanese-born property. The amount of rice available in the province decreased from about 2.3 to about 1.8 liters per person between 1912 and 1918.

As the “granary” of the empire, Chosen was supposed to support all other provinces. This is why more and more rice has been exported to the other Japanese provinces over the years (as planned, usually increasing). So was z. B. 1919 the sales quota for rice was 1/6 of the total rice production (equivalent to 64.7 million bushels of rice).

Due to the decline in the available amount of rice and the increasing demand for rice (also due to the war) in the other provinces of the empire, agriculture in the thirties was increasingly oriented towards the cultivation of rice , while traditional peasant agriculture with vegetables such as cabbage, Radish, garlic and spring onions, a little livestock farming (for self-sufficiency and as lease levies) and - as far as possible in the warmer south - silkworm breeding has been displaced. The rice cultivation area was expanded from 14,890 km² (1919) to 17,360 km², while the total agricultural area grew by a smaller area from 43,700 km² to approx. 44,520 km².

Although the planned target to increase the rice yield by approx. 75% was far from being achieved, exports to the other provinces of the empire were increased as planned. In 1933 more than half of the harvest was given away. Failure to meet the target is due, among other things, to the increase in Chōsen's population from 17 to approx. 23 million.

The rice monocultures led to a one-sided economic dependency of the farmers, who got into trouble with poor harvests or only low yields, especially since the rent costs for fertilizer and transport were added. This led to many court duties; In 1939, after giving up their farms, 340,000 households ran “nomadic farming” through slash and burn in remote mountain areas. In this way, further parts of the farming land came to people of Japanese origin.

Most of the fishing industry was taken over by (small) Japanese-born companies, the fleet was modernized and the economy intensified. In the high years, up to 90,000 fishermen were active off the coast of Chōsen. The same applied to forestry.

Industry and mining

While the colonization of Korea originally took place under military aspects as a deployment area against China - there in particular Manchuria - and Russia and under economic aspects as a sales region for industrial products, industrial exploitation only came to the fore in the twenties: low wages and long working hours promised investors in the energy industry ( hydropower ) and the chemical industry (for fertilizers and above all ammunition) high returns. In line with military needs, the chemical industry has quadrupled its production since 1925, and Chōsen's steel, coal, tungsten and lead were mainly extracted in the north. The industrial workforce rose from 50,000 workers (1911) to 1.5 million workers (1945), most of them forced labor.

The Japanese Empire opened up (for itself) the province through transport , energy supply and communication networks . Unless destroyed during the war, these networks and supply complexes could continue to be used for Korean purposes after 1945.

Forced labor and forced prostitution

From 1938 onwards, in the course of this labor mobilization, hundreds of thousands of young people and experienced workers of both sexes were compulsorily organized into the National Labor Service, which comprised around 750,000 units, and - similar to the forced laborers from all over Europe in Germany - had to work in mines and factories throughout the Japanese Empire replace men of Japanese descent required for military service. There they were forced in their little free time to visit Shinto shrines and there to pray for the success of Japan's sacred mission in Asia and for the victory over China. It is believed that there were around two million forced laborers between 1930 and 1945. On the day of the surrender, around 2.3 million people of Korean origin lived on the main Japanese islands, well over 30% of the victims of the atomic bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were Korean-born forced laborers: 40,000 of the 140,000 dead and 30,000 radiation victims.

The population remaining in Chosen was organized into neighborhood troops, each comprising 10 households and collecting taxes and other charges for the provincial government. While the rice grown in Korea was collected as a levy in kind - as is customary in premodern Japan - these neighborhood troops distributed barley and other, less food for the population to eat. Regular events such as the "Patriotic Day" launched around 1937 and the "Day in the Service of the Ascent of Asia", which were united in 1939: the first day of each month was the common compulsory work of the people of Chōsen for the Second World War dedicated.

Colonial policy intensified, especially from 1940 and even more intensely from October 1943: Thousands were convicted and imprisoned as " thought criminals", "undesirable persons" and "rebels".

From Chōsen - as from other Japanese-controlled areas - many thousands of young girls and women were kidnapped to the fronts and raped there in rows in soldiers' brothels for years; these war victims are euphemistically called comfort women . After the end of the Second World War, they often lived in Japan and in their Korean homeland as ostracized and hid. It was not until demonstrations in the 1990s and the establishment of the private Japanese Asia Women's Fund based on confessions from former Japanese officers that their fate was made public to a wider public. Since the Japanese government does not recognize any state responsibility to this day and does not open the government archives, one has to rely on estimates when assessing the numbers, which range (for all of Asia) from 50,000 to 300,000, a large part of which is said to come from Chosen.

military

After the incorporation of Korea, a large number of military police were raised. In addition, the Chosen Army was made responsible for Chosen as the colonial army of the Imperial Japanese Army . In 1915, recruits for the 19th and 20th divisions were raised from the population of Chōsen, both of which remained in Chōsen until 1937.

The Japanese military began recruiting men of Korean origin on February 22, 1938. These were used in particular in the infantry. At first - similar to Nazi Germany for racial reasons - people were very cautious and only accepted very few of the volunteers, for example only 1,280 of 15,294 candidates in 1938/39. However, this changed after the spread of the military conflicts. In the course of the labor mobilization, around 50,000 people of Korean descent from the above 350,000 forced laborers were admitted to military service and drafted. This was done despite significant concerns about their reliability. They were therefore only included after extensive review.

There was also strong pressure on the 6,500 Korean students (1943) (exceptions: medicine and technical subjects) in Japan, of whom 5,000 were drafted into the Imperial Japanese Army ; many fled and hid in Chosen Province or Manchukuo , and most of them ended up in court . There were also people of Korean origin who volunteered for military service. These underwent training and service in the Japanese army, often in the hope of being able to serve a future free Korea as trained and experienced soldiers.

Korean political and military resistance

After the collapse of the volunteer army in Manchuria in 1915 , a real army was formed there from 1920 with the participation of the " Korean Provisional Government ", which was founded in 1919 after the incident on March 1st in Shanghai, on the one hand against the Japanese occupation in the Far East Region of Soviet Russia and was forcibly accepted into the Red Army after the expulsion of the Japanese , on the other hand fought more successfully in Manchuria against the Kwantung Army , for example in the four-day battle at Cheongsan-ri in October 1920.

The conquest of northern China during and after the Second Sino-Japanese War cut off supplies for the Korean Volunteer Army. There was only the possibility of underground attacks, in particular by the "Korean Patriotic Legion" established in 1930 by the President of the government-in-exile Kim Gu (since 1927):

- Unsuccessful grenade assassination attempt on January 8, 1932 on the Japanese Emperor Hirohito in Tokyo by Lee Bong-Chang

- Bomb attack on April 28, 1932 in Shanghai by Yoon Bong-Gil on the military leadership of the invasion troops in China, the u. a. the commanders-in-chief of the fleet and the army fell victim.

After 1933, Chiang Kai-shek admitted Korean cadets to the Chinese military academy, for the first time since 1905 the regular training of Korean officers was possible again. It was only after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor , on which the government-in-exile declared war on Japan and Germany on December 9, 1941, that Kim Gu succeeded in making her voice heard internationally from her Chinese exile with the Euro-American Liaison Committee in Washington . She sent observers to the Cairo Conference in 1943 and, at the suggestion of Chiang Kai-shek , the plan for Chōsen's future independence and independence was integrated into the Cairo Declaration . As a result, special forces in the Pacific region were also expanded in cooperation with the US OSS , with the aim of deploying them in the conquest of Chōsen.

After 1943, regular Korean units were formed, which fought on the side of the Allies on the Chinese front and in the Pacific War; In addition, Korean emigrants and deserters from the Japanese army belonged as individuals and groups to individual armies of the Allies, including the communist groups around Kim Il-sung , who served as captain battalion commander in the Second Far Eastern Army of the Red Army .

Approaches to Korean Self-Government

From the beginning of August 1945, the Japanese administration under the Governor General Abe Nobuyuki prepared to hand over the colony, which was no longer tenable due to the war, to the local population in order to prevent a power vacuum and enable their own people to withdraw in an orderly manner. On August 8, Yuh Woon-hyung declares his willingness to rebuild a Korean self-government and to form a government: the Korean People's Government (KVR) with Yuh Woon-hyung as deputy prime minister .

End of the colonial era

Towards the end of World War II , the US and the USSR failed to reach an agreement on Korea's future. The Cairo Declaration of 1943 stated that Korea should form an independent state after the surrender of Japan . However, this should only take place after a certain transition period ( "in due course" ), as both sides were of the opinion that the country had to be completely rebuilt politically and economically after years of foreign rule. The Soviet Union finally accepted the US proposal to temporarily divide Korea into two zones of occupation along the 38th parallel . The northern zone was to be placed under Soviet administration, the southern half under US administration. At first the Americans wanted to leave the peninsula completely to the Soviets.

On August 8, 1945, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan, after the neutrality pact with Japan had been terminated on April 5, 1945 . The Soviet Union thus fulfilled its commitment made at the Yalta Conference to the exact day to start the war in Europe in the Far East 90 days after the end of the war and to attack Japan and its allies. The Red Army occupied during the Soviet invasion of Manchuria , the Manchuria (resp. The Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo ), then came but most of the Korean peninsula to a halt because their was not enough fuel. The Korean Liberation Army did not reach the peninsula from China either when Japan capitulated on August 15, 1945 after the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki .

After the official surrender of Japan ( radio address by the Tennō, Emperor of Japan ), but before the signing of the surrender document on September 2, 1945 on the battleship Missouri , the Red Army occupied the north of Chōsen Province and set up a Soviet civil administration there in August 1945. The Americans, however, under General John R. Hodge , landed in Jinsen on September 8th to occupy the southern part. According to a proposal by Dean Rusk , all Japanese military personnel still remaining in the colony had to surrender north of the 38th parallel to the Red Army, south of the same to the US Army. Both occupying powers initially rejected Korean self-government.

While occupied Japan and the north were placed under Chōsen's civil administrations, the United States established a military government in its southern zone of occupation . Abe, who tried to take his own life on September 9, but then surrendered to the Americans, was not released from his post as governor-general until September 12, 1945. From the surrender to this point in time, the KVR had taken over the administration of the province under Japanese supervision. Even after that, Japanese colonial officials were kept in their offices for years because they knew their colony very well.

Today we consider both in North and in South Korea August 15, 1945 as the day of independence , although Japan at least in the south de facto until 12 September 1945 and de jure until the founding of South Korea on August 15, 1948, the territorial sovereignty for all Korea owned. The validity of the annexation treaty and thus the validity of the incorporation of Korea into the Japanese national territory is currently in dispute between North and South Korea. Japan declared its final surrender of territorial sovereignty over Korea in the peace treaty of San Francisco on September 8, 1951.

The development towards two separate states

Korean self-government versus UN mandate

The victorious powers agreed to reject an independent Korea: The Foreign Ministers' Conference in Moscow from December 14 to 23, 1945 decided on a four to five year trusteeship and a provisional government under US supervision.

The US government wanted to keep the members of the KVR suspected of communist infiltration as well as nationalist circles away from any power. Therefore, after the administration was taken over by the Americans, the US government banned the KVR and its structures. On the other hand, they did not recognize the KPR (Daehan Min-guk Imsi Jeongbu) returning from exile with their President Kim Gu as Korean representation, and the US Commander-in-Chief Hodge rejected their delegation after his arrival.

Nevertheless, the KPR and Kim Gu, which existed until the founding of the two Koreas, played a significant role, Hodge played him and Rhee Syngman, who was returning from exile in the US, against each other. The merger of the two opponents Rhee and Kim on February 14, 1945 should accordingly prevent the “communists” around Yeo Un-Hyeon from founding a comprehensive national alliance, but this failed: the unity of the non-partisan KPR collapsed and its left wing closed new links alliance. In addition, Kim was not available for offices in a non-independent or divided Korea.

The background was a dramatic change in the world situation. The scant success of the Moscow conference, the disputes over Persian Azerbaijan, the disputes over China and Korea prompted US President Harry Truman to write his famous note, which ended with the sentence: “I'm tired of babying the Sovjets.” This attitude stands for the beginning of the containment policy and the "Cold War" .

Korean disputes

The influence of the Korean opponents on the future fate of Korea is therefore limited, even if the murder and manslaughter of (total) four party leaders that accompanied the disputes within four years does not show any stability or cross-party orientation in politics. However, this dispute must also be attributed in part to the policies of the US government, which favored the easier-to-manage Rhee and wanted the establishment of two states, at least one of which was under US influence. Parallels to the following development in Germany are abundantly clear.

The alliance between Rhee and Kim broke up over the question of trusteeship and the establishment of a South Korean state by the US government. The attempt by Kim Gu to stop the development of the partition of Korea through inter-Korean conferences on February 25, 1947 and April 20, 1948 with groups from the north under Kim Il-sung , ended without result. After elections on May 10, 1948 under UN supervision in the US occupation zone , in which the left-wing groups did not participate, the Republic of Korea (South Korea) was founded, succeeding the Interim Government of the Republic of Korea (KPR) . The KDVR (North Korea) emerged from the structures of the Korean People's Government (KVR), which the Soviet administration in its part of Korea had not forbidden, but influenced and directed.

Even before the elections in South Korea, due to the prevailing anti-communist hysteria, genocide-like massacres of alleged supporters of left groups were carried out under the eyes of the US military government (USAMGIK), as was the case after the Jeju uprising by farmers and fishermen on Jeju-do . Even after the South Korean government was constituted, the massacres in South Korea continued in the early 1950s.

Subsequent political and social reactions from Japan

Various Japanese politicians and Tennos have apologized for the colonial rule of their country over the Korean Peninsula. The first Japanese politician to do so was then Foreign Minister Shiina Etsusaburō in 1965 during the process of signing the Basic Treaty between Japan and the Republic of Korea : “In the long history of our two nations, there have been unfortunate times [...], it is really unfortunate and we regret it deeply. "

The first prime minister to apologize was Suzuki Zenko . In 1982, through his Chief Cabinet Secretary Miyazawa Kiichi, during the first international textbook controversy over Japanese textbooks, he said: “Japan and the people of Japan are deeply aware of the fact that past actions have caused a great deal of suffering and loss to Asian countries, including South Korea and China, and we are building the foundations of our future as a peaceful nation with that fact in mind and our determination never to let this happen again. "

In 1984 Tennō Hirohito apologized during a state visit to South Korea. Hirohito was the head of state of the Japanese Empire during the colonial period and some consider him the culprit for the time. During the state visit he said: “There has been a brief period in this century, an unfortunate past, between our two countries. This is truly unfortunate and it will not happen again. "

Japanese politicians have repeatedly apologized since the 1960s, most recently Prime Minister Naoto Kan in a public statement on August 10, 2010.

The majority of the people of Japan are open to reconciliation, including the admission of injustice, for which compensation should be made. A flat-rate collective compensation previously demanded by North and South Korea is rejected by the Japanese population. She favors making reparations specifically for affected individuals. It is their opinion that this should not be dealt with politically, but civilly; this also corresponds to the opinion of the Japanese government. The population believes that further apologies are unnecessary and unjustified in view of the aggressive pressure coming from South Korea.

Japanese neoconservatives and nationalists, on the other hand, insist - also in the textbook dispute - on a revisionist representation: They refer unilaterally to the advantages of Japanese rule for Korea and deny crimes accused of the empire such as the recruitment of slave labor and "comfort women" or the attempt to establish the Korean identity as such wipe out.

See also

- Liberation Tower

- Mansudae major monument

- Rail transport in Chosen

- Taiwan under Japanese rule

- Japanese colonies

literature

- Kim Hiyoul: Korean History: An Introduction to Korean History from Prehistory to Modern Times , Asgard 2004, ISBN 3-537-82040-2 .

- Marion Eggert, Jörg Plassen: Little History of Korea , Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-52841-4 .

- Andrew C. Nahm: A History of the Korean People - Tradition and Transformation , Seoul / New Jersey 1988, ISBN 1-56591-070-2 .

- Han Woo-Keun: The History of Korea , Seoul 1970, ISBN 0-8248-0334-5 .

- Reinhard Zöllner: History of the Japanese-Korean relations. From the beginning to the present , Munich 2017, ISBN 9783862052165 .

Web links

- Hans-Alexander Kneider, Paul Georg von Möllendorff: Minister at the Korean royal court

- English translation of the treaty on the annexation of Korea by Japan

- Hoo Nam Seelmann: Ein Leib und ein Seele , NZZ from May 5, 2007, accessed on February 17, 2018

Individual evidence

- ^ Hannes Gamillscheg: Sweden. “Moral superpower” returns , in: Die Presse, April 28, 2006.

- ^ Administrative Divisions of Countries ("Statoids") : Provinces of South Korea , accessed October 8, 2010.

- ↑ POPULATION STATISTICS : historical demographical data of the administrative division before 1950 , accessed October 8, 2010.

- ↑ Andrew Grajdanzev: Modern Korea , The Haddon Craftsmen, Inc., publication 1944, p 310 ff.

- ↑ Marc Verfürth: Japanese Militarism. In: Japan Link. Archived from the original on January 17, 2012 ; accessed on March 8, 2017 .

- ↑ The Brockhaus in Text and Image 2003 [SW], electronic edition for the office library, Bibliographisches Institut & FA Brockhaus, 2003; Article: "Korea"

- ↑ a b c d Meyer Lexikon –SW–, electronic edition for the office library, Meyers Lexikonverlag, keyword: "Korean History"

- ↑ Byong-Kuk Kim, Assassination of Empress Myongsong , Korea Times, December 28, 2001.

- ↑ JoongAng Daily : Painful, significant landmark ( memento of July 9, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ), Brian Lee, published on June 23, 2008, accessed on December 12, 2008 (English).

- ↑ Shigeki Sakamoto, The validity of the Japan-Korea Protektorate Treaty , in: Kansai University review of law and politics, Volume 18, March 1997, p. 59.

- ↑ Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures : Ito, Irobumi , 2004, National Diet Library (Japan). Retrieved October 14, 2009.

- ↑ That the annexation of Korea by Japan and the consequent expansion of the geographical scope of the Japanese treaties (i.e. their extension from 1910 to 1945, see the application of the clean slate rule to Korea after independence; Zimmermann, p. 147 ) - as far as practicable - has also been accepted by third countries on Korean territory , can be found verbatim in Andreas Zimmermann , Staatennachfuhrung in international law treaties , p. 138, there reference in footnote 40–43 to O'Connell, Succession II , p. 36 f . and Dörr, Inkorporation , p. 299 ff. ( restricted online version in the Google book search).

- ↑ Hong Chan-sik: On the Centennial of Japan's Annexation of Korea , Korea Focus, article taken from: Dong-a Ilbo, published August 13, 2010, accessed October 6, 2010.

- ^ Korea . In: Brockhaus' Kleines Konversations-Lexikon . 5th edition. Volume 1, F. A. Brockhaus, Leipzig 1911, pp. 1007-1008 . - Based on the last sentence in the encyclopedia, it can be assumed that it reflects the situation in 1910 shortly after the Japanese-Korean Unification Treaty. The reason: It is already written by a governor general and the effects of the aforementioned treaty, but it refers to a political status unchanged since 1905. Either there was a research / editing / printing error or the encyclopedia author wanted to wait until it became clear whether the international community recognized the treaty, although this answer was not yet available by the editorial deadline.

- ↑ a b James, H. Grayson: Christianity and State Shinto in Colonial Korea: A Clash of Nationalisms and Religious Beliefs . In: DISKUS . tape 1 , no. 2 , 1993, p. 17th ff . (English, Online Archive [accessed March 8, 2017]).

- ^ A b Yonhap: Today in Korean History , November 3, 2009

- ^ Gwangju anniversary , The Korea Herald, May 18, 2010

- ↑ States News Service: 82nd Anniversary of Shinganhoe's Foundation , February 12, 2009. Reproduced from a press release issued by the South Korean Minister's Office for Patriots and Veterans.

- ^ Myers, Brian R .: The Cleanest Race: How North Koreans See Themselves - And Why It Matters. (Paperback) Melville House, 2011. Pages 26-29.

- ^ East Asia Institute of the Ludwigshafen am Rhein University of Applied Sciences : Japanese occupation , accessed on April 22, 2012.

- ^ A b c Jong-Wha Lee: Economic Growth and Human Development in the Republic of Korea, 1945-1992. In: hdr.undp.org. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008 ; accessed on March 8, 2017 (English).

- ↑ YONHAP NEWS of March 26, 2010: Japan hands over list of Koreans forced into labor during colonial period. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ↑ Shigeki Sakamoto, The validity of the Japan-Korea Protektorate Treaty , Kansai University review of law and politics, Volume 18, March 1997, p. 47.

- ^ A b Yutaka Kawasaki, Was the 1910 Annexation Treaty Between Korea and Japan Concluded Legally? , Paragraph 13, Vol. 3, No. 2 (July 1996). Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ↑ Treaty of Peace with Japan , there Art. 2a; found on Taiwan Documents Project , accessed August 4, 2010.

- ↑ Christian Schmidt-Häuer: "Kill everyone, burn everything!" In: Online publication of the weekly newspaper Die Zeit . May 23, 2002, accessed December 30, 2013 .

- ^ Wong, Lee Tong: The Secret Story of the Japan-ROK Treaty: The Fated Encounter of Two Diplomats , PHP, 1997.

- ↑ Konrad M. Lawson, Japan's Apologies to Korea , in: Muninn, published April 11, 2005, accessed August 14, 2010.

- ↑ 東洋 文化 研究所 (Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia) : 歴 史 教科書 に つ い て の 官 房 長官 談話 (Address by the Chief Cabinet Secretary on the subject of history textbooks) , 東京 大学 (University of Tokyo), accessed August 14, 2010.

- ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan : Statement by Chief Cabinet Secretary Kiichi Miyazawa on History Textbooks , accessed August 14, 2010.

- ↑ Jane W. Yamazaki: Japanese apologies for World War II: a rhetorical study , Routledge, 2006, pp. 31 and 39.

- ↑ CNN International : Japan apologizes again for colonial rule of Korea , CNN Wire Staff, published August 10, 2010, accessed August 14, 2010.

- ↑ tagesschau.de : Japan's Prime Minister Kan apologizes to South Koreans ( Memento from August 16, 2010 in the Internet Archive ), by Peter Kujath, published and accessed on August 10, 2010.

- ↑ The Japan Times Online : Accepting apologies is not so easy , by Jeff Kinston, published April 2, 2006, accessed August 14, 2010.

- ↑ Isa Ducke: Status power: Japanese foreign policy making toward Korea , Routledge, 2002, p. 39 ff.

- ^ Mark E. Caprio: Neo-Nationalist Interpretations of Japan's Annexation of Korea: The Colonization Debate in Japan and South Korea , The Asia-Pacific Journal, 44-4-10, November 1, 2010.