Taiwan under Japanese rule

From 1895 to 1945 Taiwan was one of the colonies of the Japanese Empire . The expansion into Taiwan was part of the general Japanese policy of expansion southwards during the late 19th century.

Japanese rule in Taiwan is classified as significantly different from that in Korea or other parts of Asia. Since Taiwan was the first Japanese colony, the rulers wanted to make the island an exemplary "model colony". Because of this, great efforts have been made to develop the island's economy , industry , infrastructure and culture . However, Japanese rule over Taiwan also had other sides, for example Taiwanese women were forced into prostitution as so-called comfort women .

The mistakes of the Kuomintang regime after World War II created a certain nostalgia among the elderly Taiwanese who experienced both forms of rule. This hindered the establishment of a national or ethnic identity and slowed Taiwan's transition into a post-colonial era. While the Japanese are remembered on the Chinese mainland as ruthless and brutal invaders of the Sino- Japanese War 1937–1945, who were responsible for the Nanking massacre , for example , the Taiwanese memory of Japan is ambivalent. According to official statistics, more than 200,000 Taiwanese fought in the Japanese army during World War II. The transition from Japanese rule to the rule of the Kuomintang, whose leadership came almost exclusively from mainland China , was seen by many Taiwanese as a change from one foreign rule to another. The relative lack of anti-Japanese sentiments in Taiwanese society is therefore often not understood by overseas and mainland Chinese .

history

backgrounds

Japanese attempts to bring Taiwan ( Japanese : 高 砂 国 , Takasago Koku ) under control date back to 1592, when Toyotomi Hideyoshi initiated a policy of south-facing overseas expansion. Several invasions of the island failed, mainly due to disease and armed resistance from local residents. In 1609 the Tokugawa sent Haruno Arima on a research mission to Taiwan. In 1616, Murayama Toan led another unsuccessful invasion. In November 1871, a ship from the Ryūkyū Kingdom with 69 residents from the Ryūkyū Islands on board was forced by strong winds to land near the southeastern end of Taiwan. As a result, a conflict arose with the local Paiwan people , with most of the Japanese being killed. In October 1872, the Japanese Empire demanded compensation from the Chinese Qing Dynasty , with the former claiming that the Ryukyu Kingdom was part of Japan. In May 1873, the Japanese diplomats made their demands in Beijing . The Qing Dynasty immediately rejected this on the grounds that the Ryukyu Kingdom was an independent state at the time and had nothing to do with Japan. The Japanese still did not leave and asked if the Chinese government would punish the "barbarians in Taiwan". The Qing government stated that there are two types of indigenous people in Taiwan, those ruled directly by the Qing and the "raw barbarians ... beyond the reach of Chinese culture. These cannot be controlled directly. ”Indirectly, she indicated that foreigners who traveled to areas populated by indigenous peoples had to exercise particular caution. The Qing Dynasty made it clear to the Japanese that Taiwan was definitely within the Qing jurisdiction , including those parts of the island whose indigenous people were not yet under the influence of Chinese culture. The Qing also pointed to similar cases around the world in which the indigenous population within a state border was not under the influence of the dominant culture of that state.

Nevertheless, in April 1874 the Japanese sent an expeditionary force of 3,000 soldiers to Taiwan. In May 1874, the Qing sent troops to reinforce their position on the island. At the end of the year, the Japanese government decided to withdraw its troops after realizing that it was not ready for war with China. The Paiwan death toll was around 30, while the Japanese lost 543 men, of whom only 12 were killed in action - the rest died of disease.

Cession of Taiwan (1895)

In the 1890s, about 45 percent of Taiwan was administered by China, while the remaining, sparsely populated areas were under the control of the original population. In 1894, the First Sino-Japanese War broke out after a dispute over Korean independence . After its defeat, China ceded Taiwan and the Pescador Islands to Japan in the Treaty of Shimonoseki (April 17, 1895) . Under the terms of the treaty, these areas were permanently owned by Japan. Immediately after the signing of the contract, both governments had to send agents to Taiwan to start the handover process, which was completed in just two months. Although dictated by Japan conditions were tough for China, it is said that the leading Chinese statesman Li Hongzhang , the Empress Dowager Cixi was trying to appease "On the island of Taiwan any birds singing and the flowers are not fragrant. The men and women are neither obedient nor passionate. ”When the new Japanese colonial government arrived in Taiwan, it gave residents two years to recognize their new status as Japanese subjects or to leave the island.

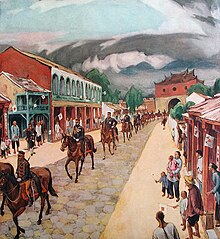

Early years (1895-1915)

The "early years" of Japanese administration usually refers to the period between the first landing of Japanese troops in May 1895 in the Japanese invasion of Taiwan and the Tapani incident in 1915, which marked the height of armed resistance. During this period popular resistance to Japanese rule was strong, and the world wondered if a non-Western nation like Japan could effectively run a colony on its own. In 1897 the Japanese Parliament debated whether to sell Taiwan to France . During these years the post of governor general was held by a general when the focus of the policy was on suppressing the resistance.

1898 appointed Meiji Tennō the Count Kodama Gentarō fourth governor general, the talented Gotō Shinpei as Director of the Department of Internal Affairs (civil governor) was used, the principle of the carrot and stick anwandte.

This marked the beginning of colonial rule (officially as the governor general's office), which was governed by Japanese law.

The Japanese attitudes towards colonial Taiwan can be roughly divided into two perspectives. The former, supported by Gotō, said that the indigenous people according to "biological principles" ( 生物学 の könnten ) could not be fully assimilated and should accordingly be governed differently. According to this theory, the Japanese should have followed the British approach, and Taiwan would never be governed in the same way as the Japanese islands, but would have received a completely new catalog of laws. The other view, supported by the later Prime Minister Hara Takashi , was that Taiwanese and Koreans were similar enough to the Japanese to be fully incorporated into Japanese society and that it was only right and fair to have the same legal and governmental system in the colonies as in Japan install yourself.

Japanese colonial policy in Taiwan largely followed the idea supported by Goto. During this period, the colonial government was authorized to pass specific laws and decrees , while also controlling the entire executive , legislative, and military power. With this absolute power, the government acted to maintain social stability while suppressing dissent.

One of the most burning problems of the time was the widespread addiction to opium. Gotō recommended a "creeping" ban on opium, whereby the sale should initially only be made by licensed dealers. At the same time, members of the local upper class who were loyal to Japan were rewarded with lucrative licenses who helped to break the foundation of the local resistance in the form of the Taiwan Yiminjun . This policy was successful in both respects. The number of addicts (recorded) fell from 169,000 in 1900 to around 62,000 by 1917 and stood at 26,000 in 1928.

Dōka: "Integration" (1915–1937)

The second period of Japanese rule generally falls between the end of the Tapani Incident in 1915 and the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in 1937, which began Japan's involvement in what would later become World War II . Events of global impact in this phase, such as the First World War , drastically changed the view of colonialism in the western world and led to growing nationalism and the desire for self-determination in the colonies themselves To make major concessions to colonies; the colonial governments were gradually liberalized.

In Japan, too, the political climate changed during these years. In the middle of the first decade of the 20th century, the Taishō period , the Japanese government had gradually democratized ( Taishō democracy ); power was concentrated in the elected parliament. In 1919 Den Kenjirō was installed as the first civil governor general of Taiwan. Before leaving for Taiwan, he consulted with Prime Minister Hara Takashi , whereupon both men agreed to pursue a policy of dōka ( 同化 , Tónghùa - "assimilation"), with Taiwan being seen as an offshoot of the original Japanese islands. Taiwanese should receive an education to understand their roles and responsibilities as Japanese subjects. This new policy was officially announced in October 1919.

This policy of adjustment was continued by the Government General for the next twenty years. As a result, local governments and an elected advisory committee were set up, the latter also including locals, albeit in an advisory capacity. A public school system was also set up. Caning was banned as a criminal punishment, and the use of the Japanese language was rewarded. This contrasted sharply with the efforts previous administrations had made on local affairs when the government's only interests were " railways , vaccination and tap water ".

Kōminka: "Subjects of the Emperor" (1937–1945)

The last period of the Japanese regime in Taiwan began with the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 and ended at the same time as World War II in 1945. With the rise of militarism in Japan in the second half of the 1930s, the office of Governor General was renewed Occupied by military personnel and Japan began to exploit Taiwanese resources to use in war. For this, the cooperation of the Taiwanese was crucial and the Taiwanese had to be fully adapted members of Japanese society. This resulted in the ban on social movements and the colonial government devoted all its efforts to the "Kōminka movement" ( 皇 民 化 運動 , kōminka undō , "Japaneseization movement"), which aimed at a fully Japaneseized Taiwanese society. Between 1936 and 1940 the Kōminka movement tried to build a "Japanese spirit" ( Yamato-damashii ) and a Japanese identity among the people. Later (1941 to 1945) the focus was on recruiting Taiwanese for military service on the Japanese side.

As part of the movement, the colonial government began to encourage the locals to speak the Japanese language , wear Japanese clothing , live in Japanese-built houses and convert to Shinto . In 1940, laws were passed recommending the adoption of Japanese names. With the expansion of the Pacific War , the government began encouraging Taiwanese to volunteer in the Imperial Japanese Army or Navy in 1942, and finally ordered a large-scale recruitment in 1945. In the meantime, laws had been passed allowing Taiwanese people to join the Japanese parliament, which in theory would have allowed a Taiwanese citizen to become prime minister of Japan.

The war inflicted heavy losses on Taiwan: on the one hand, many young Taiwanese fell while they were serving in the Japanese army, and on the other hand, the war had serious economic consequences, particularly through Allied bombing. By the end of the war in 1945, industrial production had fallen to 33% of its 1937 level and agricultural production to 49% of its 1937 level. The coal production fell from 200,000 tons to 15,000 tons.

return

See also: Japan surrender , Taiwan conflict

With the end of World War II , Taiwan was placed under the administration of the Republic of China by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) after fifty years of Japanese colonial rule . Chen Yi , who had been appointed governor of Taiwan by the Republic of China, arrived on October 24, 1945 and received the last Japanese governor-general, Andō Rikichi , who signed the deed of surrender the following day, which Chen proclaimed "day of resignation." This proved legally controversial, as Japan did not renounce Taiwan rule until 1952, further complicating Taiwan's political status. As a result, the expression "return from Taiwan" ( 台灣 光復 , Táiwān guāngfù ) is rarely used in modern Taiwan.

background

At the Cairo Conference in 1943, the Allies published a non-binding statement stating that Taiwan should return to China after the end of the war. In April 1944, the Government of the straightened Republic of China in the alternate capital of Chongqing an investigative committee of Taiwan ( 台灣調查委員會 , Taiwan Diaocha wěiyuánhuì a), whose leader was Chen Yi. Shortly afterwards, the Chiang Kai-shek committee reported on the results of the research into the island's economy, politics, society and military importance.

After the war, opinions in the Chinese government were divided on how to deal with the new area. One faction supported the idea of administering Taiwan like all other Chinese territories occupied by Japan during World War II and establishing a Taiwan Province ; the other side was of the opinion that Taiwan should be made into a special administrative zone with special military and police forces. In the end, Chiang Kai-shek decided to act on the idea put forward by Chen Yi and set up a 2000-strong "Taiwan Provincial Administration " ( 台灣 省 行政 長官 公署 , Táiwān-shěng xíngzhèng zhǎngguān gōngshǔ ) to arrange the handover.

Japan formally surrendered to the Allies on August 14, 1945. On August 29, 1945, Chiang Kai-shek announced the establishment of the Taiwan Garrison Command and the Provincial Administration of Taiwan Province on September 1, and made Chen Yi head of both units. After a few days of preparation, a better-equipped delegation with members from Shanghai and Chongqing arrived between October 5th and 24th . However, Japan did not give up complete sovereignty over Taiwan until 1952, in the San Francisco Peace Treaty . It gave up sovereignty over Taiwan and the pescadors, but did not name a recipient for the sovereignty; the legal status of Taiwan is still unclear and is reflected in the Taiwan conflict resist. Japan later signed the Taipei Treaty with the Republic of China , which aimed to transfer sovereignty to the Republic of China. Since it was concluded after the peace treaty of San Francisco , Japan no longer had sovereignty over Taiwan.

handing over

The formal handover of the island took place on the morning of October 25, 1945 in the Taipei City Hall, today's Zhongshan Hall. The governor general of Taiwan handed over the island of Chen Yi as a representative of the allied troops in Southeast Asia.

In the Republic of China, the date is commemorated with the Taiwan Return Day .

The office of governor general

The highest colonial authority in Taiwan was the office of the Governor General of Taiwan ( traditional : 臺灣 總督 府 / modern : 台湾 総 督府 , Taiwan sōtokufu ), which was headed by the Governor General, who was appointed from Tokyo during the Japanese rule . Power was highly centralized, with the governor general holding supreme executive , legislative and judicial powers , effectively making the governor a dictator.

development

In its earliest form, the governor general's office had three divisions: domestic affairs, army, and navy. The domestic affairs office was further divided into internal affairs, agriculture, finance and education. The offices for army and navy were merged into a single office for military affairs in 1896. Further reforms in 1898, 1901 and 1919 gave the Office of Domestic Policy three additional offices: General Affairs, Justice and Communication. This arrangement lasted until the end of Japanese rule.

Governors General

During the entire Japanese colonial period in Taiwan, the office of governor general remained de facto the central authority in Taiwan. Policy formulation and development was primarily the task of the central or local bureaucracy. In the 50 years of Japanese rule from 1895 to 1945, Tokyo sent nineteen governors-general to Taiwan. On average, a governor general served about two and a half years. The entire colonial period can be further divided into three periods according to the governor's background: the earlier military period, the civil period and the later military period.

The governors-general of the previous military period were Kabayama Sukenori , Katsura Tarō , Nogi Maresuke , Kodama Gentarō , Sakuma Samata , Ando Sadami and Akashi Motojirō . Two of them, Nogi Maresuke and Kodama Gentarō, later became famous in the Russo-Japanese War . It is generally accepted that Andō Sadami and Akashi Motojirō did most of their tenure for the interests of Taiwanese people; In his will, Akashi Motojirō even wished to be buried in Taiwan.

The civil period occurred around the same time as the democratic Taishō period ( Taishō democracy ) in Japan. Governors-general from these years were mostly nominated by the Japanese parliament - their names were Den Kenjirō , Uchida Kakichi , Izawa Takio , Kamiyama Mitsunoshin , Kawamura Takeji , Ishizuka Eizō , Ōta Masahiro , Minami Hiroshi and Nakagawa Kenzō . During her tenure, the governorship devoted most of its resources to economic and social development rather than military repression. The governors-general of the later military period focused primarily on supporting the Japanese war effort. The governors at that time were Kobayashi Seizo , Hasegawa Kiyoshi and Ando Rikichi .

Director of the Internal Affairs Office

The Director of the Internal Affairs Bureau directly carried out colonial policy in Taiwan, making him the second most powerful individual within the governor-general's office.

Administrative units

In addition to the governor general and the director of the internal affairs office, the governorship consisted of a strictly hierarchical bureaucracy that included law enforcement , agriculture , finance , education , mining , foreign affairs and judicial affairs departments. Other government bodies included courts of law , penal institutions , orphanages , police academies , transportation , port authorities , monopoly offices , schools , an agricultural and forestry research station, and the Taihoku Imperial University , now Taiwan National University .

Taiwan was divided into prefectures for local government . These prefectures became the basis of the administrative division of the Republic of China in Taiwan after 1945 . From 1926 the following prefectures were established:

| Name of the prefecture | Area (km², 1941) |

Population (1941) |

Modern units | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rōmaji | Kanji | Kana | |||

| Taihoku | 臺北 州 / 台北 州 | た い ほ く し ゅ う | 4,594 | 1,140,530 | Taipei , New Taipei , Yilan County , Keelung |

| Shinchiku | 新竹 州 | し ん ち く し ゅ う | 4,570 | 783.416 | Taoyuan , Hsinchu , Hsinchu County , Miaoli County |

| Taichu | 臺中 州 / 台中 州 | た い ち ゅ う し ゅ う | 7,382 | 1,303,709 | Taichung , Changhua County , Nantou County |

| Tainan | 臺南 州 / 台南 州 | た い な ん し ゅ う | 5,421 | 1,487,999 | Tainan , Chiayi , Chiayi County , Yunlin County |

| Takao | 高雄 州 | た か お し ゅ う | 5,722 | 857.214 | Kaohsiung , Pingtung County |

| Taitō | 臺 東 廳 / 台 東 庁 | た い と う ち ょ う | 3,515 | 86,852 | Taitung County |

| Karenko | 花蓮 港 廳 / 花蓮 港 庁 | か れ ん こ う ち ょ う | 4,629 | 147,744 | Hualien County |

| Hoko | 澎湖 廳 / 澎湖 庁 | ほ う こ ち ょ う | 127 | 64,620 | Penghu County |

Armed resistance

Most of the armed resistance to Japanese rule occurred during the first twenty years of the colonial period. This period of resistance is usually divided into three phases: the defense of the Formosa Republic , guerrilla warfare after the fall of the republic, and finally the phase between the Beipu Uprising of 1907 and the Tapani Incident of 1915. Later, the armed resistance was largely carried out replace peaceful forms of cultural and political activism ; the most notable exception is the Wushe incident .

The Republic of Formosa

The decision of the Qing government to cede Taiwan to the latter after the Chinese defeat against Japan with the Treaty of Shimonoseki caused massive resistance on the island. On May 24, 1895, an English translation of the Declaration of Independence was delivered to all embassies on the island in order to demand the assistance of Western powers; the following day the republic was proclaimed: a group of Qing-loyal officials and local dignitaries proclaimed independence from China and a new Formosa republic whose aim was to keep Taiwan under Qing control; the then Qing governor Tang Jingsong was installed as the first president against his will. Japanese troops landed in Keelung on May 29th ; the city was captured on June 3rd. The following day, President Tang and Vice President Qiu Fengjia fled to China. At the end of June, the remaining supporters of the republic gathered in Tainan and elected Liu Yongfu as second president. After skirmishes between Japanese and Republican forces, the Japanese captured Tainan in late October. Soon after, President Liu fled to China. Although there were still defensive troops in southern Taiwan, they had to surrender on October 21 and the history of the republic was over in 184 days.

Guerrilla warfare

As a result of the collapse of the Republic of Formosa, Governor General Kabayama Sukenori reported to Tokyo that the island was secure and began to establish the administration. However, in December 1895, several anti-Japanese uprisings occurred in northern Taiwan. The surveys continued, at a frequency of about one per month. By 1902, however, most anti-Japanese activity among the Taiwanese population had ceased, with 14,000 Taiwanese (0.5% of the population) killed. Taiwan remained relatively calm until the Beipu uprising in 1907. The reason for this five-year hiatus is believed to be the governor-general's ambiguous policy, which consisted of active repression and community service. With this carrot and stick strategy, most Taiwanese chose to wait and watch.

Tapani incident

The third and final phase of the armed resistance began with the Beipu uprising in 1907. Between this and the Tapani incident of 1915 there were thirteen minor armed uprisings. In many cases the conspirators were discovered and arrested before the planned uprisings could even take place. Of the thirteen uprisings, eleven took place in China after the Xinhai Revolution of 1911, and four were directly related. The leaders of four of the uprisings called for reunification with China, while six other uprisings sought the installation of their leaders as rulers of an independent Taiwan. In one case the ringleaders could not decide which goal to pursue. The plans of the conspirators for the remaining two surveys are unclear. It has been speculated that the rise in uprisings in favor of independence over reunification was a result of the collapse of the Qing Dynasty government in China, which deprived Taiwanese residents of the government with which they had previously identified themselves.

Wushe incident

Perhaps the most famous of all anti-Japanese uprisings is the Wushe Incident , which took place in the Musha ( 霧 社 , Chinese: Wushe) region in Taichū Prefecture (in what is now Nantou County ). On October 27, 1930, following an incident in which a Japanese police officer insulted a tribesman , over 300 Sediq under Chief Mona Rudao attacked Japanese residents in the area. In the ensuing violence, 134 Japanese and two Han Taiwanese were killed and 215 Japanese were injured. Many of the victims took part in a sports festival at Wushe Elementary School ( 霧 社 公 学校 Musha kōgakkō ). In return, the governor general ordered a punitive expedition. In the following two months, most insurgents were either killed or committed with their families or other members of the tribe suicide . Several members of the government resigned over what was the bloodiest of the uprisings under Japanese rule. This uprising was filmed in Warriors of the Rainbow: Seediq Bale .

Economic and Educational Development

One of the most important features of Japanese rule in Taiwan was the profound social changes. While local activism certainly played a role, most of the social, economic and educational changes during this period were driven by technocrats in the colonial government. With the office of governor general as the primary driving force and new immigrants from Japan, Taiwanese society was sharply divided between the rulers and the ruled.

Under the constant control of the colonial government, Taiwanese society was mostly very stable, with a few minor incidents in the early years. While the governor's repression tactics were often very oppressive, locals who cooperated with the government's economic and educational policies saw their living standards improve significantly. As a result, the quality of the residents' living conditions continued to grow during the fifty years of Japanese rule.

Economically

Taiwan's economy was largely a normal colonial economy under Japanese rule, meaning that the island's human and natural resources were used to aid Japan's development. This policy began under Governor General Kodama and peaked in 1943, in the middle of World War II . The state monopolies became the essential basis for state revenue. Since 1898 there was a state monopoly on the production of opium, and later monopolies on salt and camphor were added. The out of the wood of the camphor tree derived camphor was an important export and served for medical purposes, as a starting material for the production of the early plastic celluloid as well as smokeless gunpowder. In the years 1910 to 1916 Taiwan produced 56% of the camphor produced worldwide and from 1919 a state monopoly existed for the production of camphor. The state monopoly for tobacco was added in 1905 and that for alcohol in 1922. During the war the monopolies for the standardization of the weight system and for petroleum followed. The monopoly was operated from 1901 by the monopoly office at the office of the governor of Taiwan .

From 1900 to 1920, the Taiwanese industry was dominated by the sugar industry. Forestry was also of great importance. Numerous small railways were built by the Japanese colonial administration to develop the wood resources, leading deep into the mountainous interior and serving to transport the precious woods extracted there. Some of these tracks have been preserved to this day ( Alishan Forest Railway , Taipingshan Forest Railway , Luodong Forest Railway, etc.).

From around 1920 to 1930 the focus was on rice cultivation. During these phases, the governorship's main economic policy was "Industry for Japan, Agriculture for Taiwan". After 1930 the office adopted a policy of industrialization because of war needs. Under the seventh governor Akashi Motojiro, a large swamp in central Taiwan was turned into a huge dam to build a hydraulic power plant for industrialization. The dam and its surroundings, now widely known as Sun Moon Lake ( Nichigetsutan ), have become a major attraction for foreign tourists.

Although the main focus was different in each of these periods, the main goal throughout was to increase Taiwan's productivity to meet demand in Japan, a goal that has been successfully met. As part of this process, new ideas, values and concepts were introduced in Taiwan; in addition, many public work projects have been initiated, such as railways, public education and telecommunications. As the economy flourished, society stabilized, politics was gradually liberalized, and popular support for the colonial government increased. Taiwan therefore served as a model colony for Japan's propaganda for colonial aspirations in Asia, as demonstrated during the 1935 Taiwan Exhibition.

Financially

Shortly after Taiwan ceded to Japan, a small branch of a bank from Osaka opened in Keelung in September 1895 . By June of the following year, the governor-general had given the bank permission to set up the first western banking system in Taiwan. In March 1897, the Japanese Parliament passed a law establishing the Taiwan Ginko , which began operating in September 1899. In addition to the normal duties of a bank, the Bank of Taiwan was also responsible for minting the currency used in Taiwan under Japanese rule. In order to preserve the financial stability, the Office of the Governor General founded several other banks, cooperative banks and other financial organizations with a mandate in controlling inflation to help.

general school attendance

As part of the long-term government goal of keeping the anti-Japanese movement under control, public education became an important mechanism to facilitate control and intercultural dialogue. While secondary schools were mostly only accessible to Japanese, the impact of elementary education on Taiwanese was immense.

On July 14, 1895, Isawa Shūji was appointed first minister of education and proposed to the governor-general to introduce compulsory schooling for primary school children - a policy that had not even found its way into Japan at the time. As an experiment, the governor's office set up the first Western-style elementary school in Taipei (today's Shilin Elementary School). Since the results were satisfactory, in 1896 the government ordered fourteen language schools to be established, which were later converted into public schools. During this time the schools were run separately according to ethnic groups. Kōgakkō ( 公 學校 , public schools) were established for Taiwanese children, while shōgakkō ( 小學校 , elementary schools) were restricted to Japanese children. Schools have also been set up for these in the indigenous areas. A list of criteria for teacher selection has been drawn up and several teacher training schools have been set up, such as the Taihoku Normal School. Secondary schools and study opportunities largely reserved for the Japanese were also set up, such as the Imperial University of Taihoku . The focus of training for the island's residents was on vocational training to increase productivity.

The racial barriers were finally lifted in March 1941, when all but a few schools for indigenous people were re-classified as kokumin gakkō ( 國民 學校 , national schools), which were open to all students, regardless of ethnicity. School attendance was compulsory for children between eight and fourteen years of age. The subjects taught included moral education ( 修身 , shūshin ), essay ( 作文 , sakubun ), reading ( 讀書 , dokusho ), writing ( 習字 , shūji ), mathematics ( 算術 , sansū ), singing ( 唱歌 , shōka ), and exercise ( 體操 , taisō ).

By 1944, Taiwan had 944 elementary schools with enrollment rates of 71.3% for Taiwanese, 86.4% for indigenous people, and 99.6% for Japanese. As a result, primary school enrollment rates in Taiwan were the second highest in Asia, surpassed only by Japan itself.

population

As part of the vigorous government control of Taiwan, the governorate conducted detailed censuses every five years , beginning in 1905. Statistics show the population grew from 0.988% to 2.835% per annum during Japanese rule. In 1905 Taiwan had a population of around 3.03 million; in 1940 the number was 5.87 million. Another six years later the population was 6.09 million.

Transport developments

The governorship also vigorously modernized Taiwan's transportation system, including railways in particular and, to a more limited extent, roads. This resulted in the establishment of reliable transit connections between the northern and southern ends of the island, which further supported the population growth.

Railways

The Ministry of Railways was established on November 8, 1899, which began a period of rapid expansion of the island's rail network. Possibly the greatest success of this era was the completion of the western route in 1908, and thus the connection of the most important cities in the western corridor. This route reduced the travel time between northern and southern Taiwan from several days to a single day.

Other routes built during this period were the Tansui route ( 淡水 線 , today the Danshui route of the MRT ), the Giran route ( 宜蘭 線 , Yilan route), the Heitō route ( 屏東 線 , Pingtung route) and the Tōkō route ( 東 港 線 , Donggang route). Several private railway lines such as the Zuckerbahn were also built and incorporated into the state-owned system, as were industrial lines such as the Alishan Forest Railway , Taipingshan Forest Railway or Luodong Forest Railway . Plans were also drawn up for various additional routes, for example a northern and southern connecting line or a route over the central Taiwanese mountains. However, these plans were never realized because of technical difficulties and the outbreak of World War II.

Like many other government offices, the Ministry of Railways was run by technocrats . Many of the railway lines constructed at the time are still in use today.

Highways

Compared to the rapid development of the railway network, the road system received significantly less attention. However, in the face of increasing competition from motorized vehicles, the Ministry of Railways began to buy or confiscate roads running parallel to railroad lines.

Bus services were available in urban areas, but since the Taiwanese cities were very small at the time, buses were always secondary to the railways. Most of the bus routes had the local train stations as centers.

Social policy

While the Gotō-supported idea of a special form of government influenced most of the political decisions made by the colonial government, the ultimate goal remained modernization. With these ideals, the colonial government, together with social associations, wanted to exert pressure on Taiwanese society to gradually modernize itself. These efforts were mostly aimed at what are known as the "Three Bad Habits".

"The three bad habits"

The “Three Bad Habits ” ( 三大 陋習 ) were viewed by the governor as archaic and unhealthy. These three ancient customs were the use of opium , the tying of the feet and the wearing of braids . As in mainland China, opium addiction was a serious social problem in Taiwan in the 19th century; some statistics claim that over half of the Chinese population in Taiwan were users of the drug. The deliberate disfigurement of female feet by tying them up and breaking bones and wearing braids for men were also common in China and Taiwan during this period.

opium

Shortly after the acquisition of Taiwan in 1895, the then Prime Minister Itō Hirobumi ordered that opium should be banned in Taiwan as soon as possible. However, because of the pervasiveness of opium addiction in Taiwan society at the time and the social and economic problems caused by the total ban, the initial hard line was relaxed after a few years. On January 21, 1897, the Taiwanese governorate passed an Opium Act that gave the government a monopoly on the opium trade and restricted the sale of opium to government license holders. The ultimate goal was the ultimate eradication of addiction in Taiwan. The number of opium addicts in Taiwan fell rapidly from a few million to 169,064 in 1900 (6.3% of the population) and 45,832 (1.3% of the population) in 1921. Yet the numbers were still higher than in the nations in which opium was completely banned. It is generally believed that the profit achievable through a state drug monopoly was an important factor in the governorship's reluctance to ban opium entirely.

In 1921 the Taiwan People's Party accused the colonial government before the League of Nations of indifferent to the addiction of over 40,000 people and of profiting from the sale of opium. To avoid controversy, the governor general's office enacted a new opium law for Taiwan on December 28, and disclosed the details on January 8 of the following year. The new laws reduced the number of opium permits, opened a rehabilitation clinic in Taipei and launched a targeted anti-drug campaign.

Tying your feet

The tying of the feet was a fashionable practice in China during the Ming and Qing dynasties . Young girls' feet, usually around the age of six but often younger, were wrapped in tight bandages so that they could not grow normally, broke, and were deformed and crippled as they reached adulthood. The feet remained small and prone to infection, paralysis, and muscular atrophy . While such feet were considered by some to be an ideal of beauty, others described the practice as archaic and barbaric. Together with community leaders, the governor's office launched an anti-lotus foot campaign in 1901. The custom was officially banned in 1915; Breaking the law was severely punished. After that, foot tying soon died out in Taiwan.

Braid

The governor's office paid comparatively little attention to braids . While social campaigns against the wearing of braids have been launched, no laws or edicts have been devoted to this practice. After the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911, the compulsory braid was also abolished in China.

urban planning

Initially, the governor general's office focused on urgent needs such as sanitation and military fortifications. Urban development plans were first drawn up in 1899; these plans followed a five-year development plan for most medium-sized and larger cities. The focus of the first phase of urban redevelopment was on building and improving the roads. In Taihoku (Taipei), the old city walls were torn down and the new Seimonchō area ( 西門町 , now Ximending ) developed for new Japanese immigrants in their place .

The second phase of urban development began in 1901 and focused on the areas around the south and east gates of Taihoku and the areas around the train station in Taichu ( Taichung ). Main goals for the redevelopment included roads and irrigation systems, all in preparation for the arrival of more Japanese immigrants.

Another phase began in August 1905 and also included Tainan . By 1917, redevelopment projects had taken place in over seventy cities across Taiwan. Many of the plans issued at the time are still in use in Taiwan today.

Public health care

In the early years of Japanese rule, the governorate ordered the construction of public clinics across Taiwan and brought doctors from Japan to curb the spread of infectious diseases . The company was successful in eliminating diseases such as malaria , plague and tuberculosis from the island. The health system under Japanese rule was dominated by small local clinics rather than larger central hospitals, a situation that remained the same in Taiwan until the 1980s.

The governor's office went to great lengths to develop an effective sewage disposal system for Taiwan. British experts were hired to design gullies and sewer systems. The expansion of streets and sidewalks, the introduction of building codes that required windows and thus an exchange of air, and quarantine of the sick all helped to improve general health.

Health education also became increasingly important in schools and in law enforcement. Taihoku Imperial University established a tropical disease research center and nurse training facilities.

native people

According to the 1905 census, Taiwan at that time had 450,000 native people of the plains (15.3% of the total population), almost entirely adapted to Han Chinese society, and over 300,000 mountain people (12.0% of the total population). The Japanese "indigenous policy" mainly focused on the maladjusted hill tribes, known in Japanese as Takasago-zoku ( 高 砂 族 , "Taiwan tribes").

The indigenous groups were subject to modified versions of the criminal and civil law. The aim of the colonial government, as with the rest of the islanders, was the admission of the indigenous people into Japanese society. This goal should be achieved through a double policy of oppression and education . The Japanese upbringing of Taiwan's indigenous people particularly paid off during World War II, when the Taiwan's indigenous peoples were the most daring soldiers the Empire had ever produced. Their legendary courage is still celebrated today by Japanese veterans . Many of them would say they owed their survival to the Takasago-hei ( 高 砂 兵 , "Taiwan soldiers").

religion

During most of the Japanese colonial rule, the governorship decided to promote the existing Buddhist religion in Taiwan more than Shinto . It was believed that properly used religion could accelerate the assimilation of Taiwanese into Japanese society.

Under these circumstances, the existing Buddhist temples in Taiwan were expanded and adapted to incorporate Japanese elements of the religion; such as the worship of Ksitigarbha , which was popular in Japan at the time, but not in Taiwan. The Japanese also built numerous new temples across Taiwan, many of which ended up combining elements of Daoism and Confucianism , a mixture that still exists in Taiwan today.

In 1937, with the beginning of the Kōminka movement, the government began to support the Shinto and to restrict other religions to a certain extent.

Culture

After 1915, the armed resistance against the Japanese occupation largely ceased. Instead, spontaneous social movements became popular. The Taiwanese people organized various modern political, cultural and social associations and assumed political consciousness. This motivated them to zealously for goals that were often picked up by social movements. These movements strove for social improvement.

Along with Taiwanese literature associated with the social movements of the period, the most successfully absorbed aspect of Western culture by Taiwan was the arts. Many famous works of art date from this period. For the first time during this period, folk culture dominated by films, folk music, and puppet shows took hold in Taiwan.

literature

In 1919, Taiwanese students in Tokyo reorganized the Enlightenment Society and established the New People's Society. This was the prelude to various political and social movements. Many new publications were started shortly thereafter, such as "Taiwanese Literature and Art" (1934) or "New Taiwanese Literature" (1935). This led to the beginnings of the national language movement in Taiwan and the departure from the classical forms of poetry. Many scholars acknowledge possible links with the May Fourth Movement in China.

These literary movements did not go away when they were suppressed by the Japanese governor. In the early 1930s, a famous debate about the Taiwanese rural language unfolded. This debate had numerous lasting effects on Taiwanese literature, language, and ethnic awareness.

In 1930, Huang Shihui began the rural literature debate in Tokyo. He argued that Taiwanese literature should be about Taiwan, have an impact on the widest possible audience, and use the Taiwanese language . In 1931, a Taipeian writer Guo Qiusen , who supported Huang's views, started a debate defending literature published in Taiwanese. This was immediately supported by Lai He , who is known as the father of Taiwanese literature. Later, questions about whether Taiwanese literature should be published in Taiwanese or Standard Chinese , and whether Taiwan should be written about, became the focus of the New Taiwan Literature Movement. However, because of the emerging war and ubiquitous Japanese cultural education, the debate was unable to advance. The movement soon lost traction because of the policies of Japanization implemented by the government.

In the two years after 1934, progressive Taiwanese writers united to form the Association of Taiwanese Literature and Art and the New Taiwanese Literature. This art and literary movement had political consequences. After the incident at the Marco Polo Bridge in 1937, the colonial government of Taiwan immediately introduced the “general mobilization of the national spirit”. Taiwanese writers could then rely only on Japanese-dominated organizations, such as the "Taiwanese Poets Society", which was founded in 1939, and the "Society of Taiwanese Literature and Art" from 1940. Taiwanese literature focused mainly on the Taiwanese spirit and nature of Taiwanese culture. Although it seems normal, it was actually a revolution made possible by political and social movements. Artists began to think about Taiwanese culture and tried to build a culture that really belonged to Taiwan.

Western art

During the reign of the Qing Dynasty , the concept of Western art did not exist in Taiwan. Painting was not a highly respected occupation, and even Chinese landscape painting was poorly developed. When the Japanese took over Taiwan in 1895, they brought with them a new system of education that included training in Japanese and Western arts. This not only laid the foundation for the later recognition of the art in Taiwan, but also produced various famous artists. Painter and teacher Ishikawa Kinichiro made an immense contribution to planning the training of new art teachers. He also taught students himself and encouraged them to travel to Japan themselves and learn more sophisticated art techniques.

In 1926, a Taiwanese student in Japan named Chen Chengpo presented a work called On the Outskirts of Jiayi (see picture). His work was selected to be featured at the Seventh Imperial Japanese Exhibition. It was the first Western-style artwork by a Taiwanese artist to be included in a Japanese exhibition. Many other works were subsequently shown at the Imperial Japanese and other exhibitions. These successes made it easier for the arts to spread in Taiwan. Ironically, after the incident of February 28, 1947 , Chen, who is valued by the Japanese, was executed by the Chinese without a trial for being a "bandit".

What really built the arts in Taiwan was the introduction of official Japanese exhibitions in Taiwan. In 1927 the governor of Taiwan set up the Taiwanese Art Exhibition together with the artists Ishikawa Kinichiro , Shiotsuki Toho and Kinoshita Shizukishi . This exhibition was held sixteen times between 1938 and 1945. She raised the first generation of Taiwanese western-style artists.

Movie

Between 1901 and 1937, Taiwanese film was heavily influenced by Japanese film . Because of Taiwan's status as a Japanese colony, the traditions of Japanese film have been widely accepted by Taiwanese directors. The first Taiwanese film was a documentary produced by Takamatsu Toyojiro in February 1907 - with a group of photographers touring various areas in Taiwan. Their production was called "Description of Taiwan" and featured subjects such as urban construction, electricity, agriculture, industry, mining, railways, education, landscapes and traditions. The first Taiwanese-produced drama film was "Whose Mistake?" From 1925, produced by the Taiwanese Film Research Society. Other types of film, such as educational films, newsreels, and propaganda , also helped shape the mainstream of local films until the defeat of Japan in 1945. The film Sayon's Bell , which portrays an indigenous girl who helps Japanese, was a symbolic production that represents these types of films.

In 1908, Takamatsu Toyojiro settled in Taiwan and began setting up cinemas in major cities. Takamatsu also signed contracts with numerous Japanese and foreign film companies and established the production of films in film studios. In 1924, Taiwanese cinemas imported advanced subtitle technology from Japan and the importance of cinemas grew. A celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the Japanese occupation was held in October 1935, and Taipei and Fukuoka were connected by a beeline the following year . These two events led Taiwan cinema into its golden age.

Light music

Popular music emerged in Taiwan in the 1930s. Although published recordings existed before that time, the quality and popularity of most were limited. The main reason was that the songs at that time differed somewhat from traditional music such as folk music or Taiwan opera . However, thanks to the rapid development of cinema and radio during the 1930s, songs began to appear that had moved away from traditional influences and were rapidly spreading.

The first real “hit song” in Taiwan went hand in hand with the Chinese film Peach Blossoms Weep Tears of Blood (Tao hua qi xie ji) by Bu Wancang . The film, produced by the Lianhua Film Company and starring the young stars Ruan Lingyu and Jin Yan , was shown in Taiwanese theaters in 1932. Hoping to attract more Taiwanese visitors, the makers commissioned composers Zhan Tianma and Wang Yunfeng to develop a song with the same title. The resulting song was a huge hit and achieved record sales. Since then, popular music began to unfold with the help of cinema.

Puppet theater

During the 1850s, many Min Nan speaking immigrants came to Taiwan and brought the puppet theater with them. The stories were mostly based on classic books and stage plays and very sophisticated. The art was in the complexity of the puppet movements. The musical accompaniment generally consisted of Nanguan or Beiguan music , with Nanguan being the earliest form of puppet theater in Taiwan. Although this type of puppet theater has gone out of fashion, it can still be found with some troops around Taipei.

During the 1920s, wuxia puppet theater slowly developed . The biggest difference between traditional theater and wuxia theater are the stories. In the latter, the actions were based on new, popular wuxia novels and the performances were focused on the sole representation of martial arts with the dolls. The representative figures of this era were Huang Haidai from Wuzhouyuan and Zhong Renxiang from Xinyige. This genre of dolls began development in the cities of Xiluo and Huwei in Yunlin and became popular in southern central Taiwan. Huang Haidai's puppet show was narrated in Min Nan and included poetry, story and rhymes, among other things. The performances were accompanied by Beiguan, Nanguan, Luantan, Zhengyin, Gezai and Chaodiao music.

From the 1930s onwards, the policy of Japanization affected the puppet theater. Traditional Beiguan music was banned and replaced by Western music. The costumes and dolls were a mix of Japanese and Chinese styles. The plays often included Japanese stories such as Mito kōmon , with the dolls wearing Japanese clothing. Performances were shown in Japanese . This new language and cultural barrier reduced public acceptance, but introduced techniques that then influenced the later gold-light puppet theater, such as music and stage sets.

During this time, the world of puppet theater in southern Taiwan included the Five Great Pillars and the Four Great Celebrities. The "Five Great Pillars" refer to Huang Haidai, Zhong Renxiang, Huang Tianquan, Hu Jinzhu, and Lu Chongyi; the "Four Great Celebrities" refer to Huang Tianchuan, Lu Chongyi, Li Tuyuan and Zheng Chuanming.

baseball

Even the baseball game was brought by the Japanese to Taiwan. There were baseball teams in both elementary schools and public schools. The development of the game in Taiwan culminated in the Kagi Nōrin (Agriculture and Forestry School) baseball team, which took second place in Japan's Kōshien Daisai (National Secondary School Baseball Games). The Japanese also built baseball fields in Taiwan, such as the Tainan Stadium. To date, baseball is one of the most popular sports in Taiwan.

Others

- According to a 2010 poll, most Taiwanese surveyed (52%) named Japan their “favorite nation abroad”.

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ 林楠森: 一个 台湾 “皇军” 的 回忆. BBC, August 15, 2008, accessed November 22, 2016 (Chinese).

- ^ Yuan-Ming Chiao: I was fighting for Japanese motherland: Lee. The China Post, August 21, 2015, accessed November 22, 2016 .

- ↑ Marcus Bingenheimer: Chinese Buddhism Unbound - Rebuilding and Redefining Chinese Buddhism on Taiwan. , 2003, digitized version

- ↑ Old camphor kingdom comes alive. Taiwan Today, July 2, 2010; accessed February 20, 2018 .

- ^ History. Taiwan Tobacco and Liquor Corporation (TTL) website, accessed March 16, 2019 .

- ↑ Taiwan's declaration of love for Japan. on: asienspiegel.ch , March 24, 2010.

literature

- Koh Se-kai (許世楷): 日本 統治 下 的 台灣Riben tongzhi xia de Taiwan ( Formosa under the Japanese Rule - Resistance and Suppression ). Yushan she, Taipei 2005, ISBN 986-7375-54-8 .

- Harry J. Lamley: Taiwan under Japanese Rule. In: Murray A. Rubinstein (Ed.): Taiwan - A New History. extended edition. ME Sharpe, New York 2007, ISBN 978-0-7656-1494-0 .

- Ping-hui Liao, David Der-wei Wang (eds.): Taiwan Under Japanese Colonial Rule, 1895–1945: History, Culture, Memory . Columbia University Press, New York 2006, ISBN 0-231-13798-2 .