Cixi

Cixi ( Chinese 慈禧 , Pinyin Cíxǐ , IPA ( standard Chinese) [ tsʰɯ2ɕi3 ], W.-G. Tz'u Hsi ; born November 29, 1835 , † November 15, 1908 in Beijing ) was a concubine of the Chinese Emperor Xianfeng and became most influential figure of the late Qing Dynasty .

General

From 1861 to 1872, Cixi led the reign of her son, the minor Emperor Tongzhi , and from 1875 to 1889 for her nephew, the minor Emperor Guangxu, as "Empress Dowager " (Chinese: huángtàihòu , 皇太后) . She resumed government in 1898 after arresting Guangxu on a pretext, and then held power until her death in 1908. She ruled longer than any other empress. Historically, she is one of the most ambiguous people in Chinese history . Domestically, Cixi tried to balance the conservative and reform-oriented fractions of the court in order to consolidate the power of the imperial family again and to stabilize the country, which was in decline. In doing so, she repeatedly made serious misjudgments of the real situation, which ended, for example, in the catastrophe of the Boxer Rebellion and a completely belated reform policy. This also had serious consequences in foreign policy; technically backward and economically stricken China now lost its hegemonic position in East Asia .

The rise of the Cixi from insignificant concubine to influential empress widow already occupied the imagination of her contemporaries. Her palace career has been associated with a series of murders, sexual perversions and intrigues , especially in the West . Decisive for this caricature of her personality was a biography of Edmund Backhouse , published as early as 1910 , which portrayed the Empress widow as a vile and degenerate personality. Novels and narratives of the western cultural area took up this and characterize Cixi as an ambitious woman who planned and managed her admission into the imperial harem and the advancement within the palace hierarchy. One of the best-known stories that thematize her life is the novel Das Mädchen Orchidee by Pearl S. Buck .

In the 1970s, various historians such as Hugh Trevor-Roper established that the Chinese sources on which Edmund Backhouse relied were forgeries. Modern historiography today paints a much more sober picture of the last regent of China as a backhouse: only because Cixi gave birth to the only son of the emperor, she was able to rise within the palace hierarchy. Apparently she only seized power because disputes over the succession of the dead emperor put both her life and the life of her child in danger.

Life

origin

Apart from her date of birth, little is known about the origin of the future Chinese regent. The maiden name of Cixi is not known, as it was against Chinese etiquette to call direct members of the imperial environment by name. During the period in which she was considered one of the imperial concubines, she was dubbed "the Lady Yehenara, daughter of Huizheng". However, this is not a maiden name, but describes her descent from the Manchu clan to which she belonged ( Yèhè Nālā Shì , 叶赫 那拉氏).

Cixi was born in Beijing in 1835 on the tenth day of the tenth lunar month, the eldest of two daughters and three sons. Her family had worked in the service of the state for generations and was accordingly wealthy and educated. Her father Huizheng initially worked as a secretary and later became head of a department in the Ministry of Personnel. He was a Manchu nobleman from the Nara clan (or Nala), which in turn was part of the Eight Banners , which distinguished themselves in the fight against the Ming dynasty in the early 17th century . Thus, Cixi comes from one of the most respected and oldest Manchu families in China. The ancestry of the family can be traced back to the grandfather of Nurhaci , the founder of the Qing dynasty . Nothing is known about her mother.

As a Manchu, Cixi was fortunate that her feet were not tied like the women of the Han. This ancient tradition saw breaking and wrapping the feet in infancy to prevent growth. She learned to read but had insufficient knowledge of written Chinese. This doesn't know an alphabet, but uses numerous complicated ideograms . She also learned to sew, play chess, embroider and draw. These were all necessary qualities that distinguished a young lady at the time and that she needed. She was interested in many things, learned quickly and eagerly. Cixi could neither speak nor write Manchu as this was not part of her training. She was able to compensate for the lack of formal education with her quick comprehension.

In 1843, when Cixi turned seven, the First Opium War ended and China had to pay heavy compensation to the British. Since Emperor Daoguang desperately needed money, festivals and celebrations had to be more modest or were canceled entirely. When the emperor ordered an inspection of the imperial treasury one day, more than 9,000,000 silver tael were missing . Cixi's great grandfather was one of the treasury overseers in charge and was therefore held accountable. His sentence was 43,200 taels. Since he had already died, Cixi's grandfather was asked to pay half the debt. But since he could only raise 1,600 tael, he had to go to jail and hoped that Cixi's father would be able to pay the debt. The family's life was thus put to the test. Cixi later told her ladies-in-waiting that she had to earn extra money doing sewing. Since she was the oldest child in the family, her father spoke openly with her about the difficult situation. She gave him thoughtful suggestions on how to collect money, and together they reached the sum necessary for the release of his grandfather. In the family annals one finds the following compliment from the father to his daughter:

"This daughter is more like a son!"

Since her father saw her like a son, he talked to her about things that were actually taboo for women. Cixi thus gained insights into state affairs, which shaped her lifelong interest. After paying his grandfather's debt, Huizheng was appointed governor of a Mongolian region in 1849. In the summer of that year, Cixi left Beijing for the first time and the family settled in Hohhot . The impressions of the fresh air and nature shaped her whole life.

Admission to the harem

When Emperor Doaguang died in February 1850, his 19-year-old son succeeded Emperor Xianfeng . Shortly after the coronation, the search for suitable wives began across the country.

The harem of a Chinese emperor in the 19th century consisted of an empress, two wives, eleven concubines and numerous concubines. The concubines, in turn, were divided into different ranks. The majority of the women in the imperial harem came from families of the Eight Banners, meaning they were either Manchu, Mongol or Han ancestry. Sometimes Koreans were also taken into the harem by Turkic peoples . The choice of wives and concubines was not made by the incumbent emperor, but usually by the widow of the previous emperor. The concubines were chosen from a number of girls who had just reached sexual maturity and were proposed by the elders of the clans. The chance that a clan member would become an influential figure in the Chinese court in this way was not very high. However, attaining such a position strengthened the influence of a single clan.

Cixi was one of the presumably twenty to thirty young Manchu women who were appointed to Beijing as possible concubines for the 19-year-old Emperor Xianfeng after a corresponding preselection in 1851 from the widow Empress Xiao Jing Chen . Cixi returned to her family's old house and waited there for the day when the candidates would be presented to the emperor. The decision was to be made in March 1852. A day before the date, Cixi was picked up by a mule cart. Although these carts had mattresses and pillows, they were very uncomfortable. The cars of all selected candidates gathered at the back entrance in the north of the Forbidden City (the southern entrance was forbidden for women) and drove into the imperial city in a corresponding order. There they stayed overnight in the northern district and waited in their uncomfortable car until dawn. Only when the gates opened with the first ray of sunlight could they get out and were brought into the hall by eunuchs , where they examined and selected court officials for the emperor. Then they were placed in a row in front of the emperor. In addition to the empress widow, court ladies and eunuchs were also involved in the selection . The selection criteria used to select the future concubines from among the candidates included health, manners, emotional balance, basic knowledge of Chinese and Manchurian and an evaluation of the horoscope . Reading and writing skills, on the other hand, were not prerequisites for admission to the harem. The girls were also not allowed to have certain body features such as irregular teeth or a long neck.

“In addition to the family name,“ character ”was the most important selection criterion. The candidates had to have dignity and good manners, be graceful, gentle and humble - and they had to know how to move around court. The exterior was secondary, but they should at least be pleasant to look at. "

Cixi was not particularly beautiful, but her expressive and bright eyes made a great impression on the emperor. She was shortlisted and had to take additional exams overnight. Cixi was chosen from among hundreds along with four other girls. She was allowed to prepare for her future role as an imperial concubine at home for a year. The second year of preparation, which began on June 26, 1852, after the two-year mandatory mourning period, took place within the Forbidden City , where Cixi was introduced to the requirements of the court ceremony . She was a sixth grade concubine and thus was of the lowest rank. When it moved into the palace, it was given the name Lan (magnolia or orchid). Presumably this is a derivation of her family name Nala (also written Nalan ). It was not until 1854 that Cixi, presumably with the help of Empress Zhen (later Empress Ci'an ), rose from the sixth to the fifth level and was given the court name Concubine Yi (懿; virtuous, chaste).

Life in the harem

The emperor's dealings with his empress, his two wives or concubines and the other concubines were subject to a number of traditional rules. These were supposed to ensure that the emperor had sexual intercourse regularly with a large number of the harem women and that he had sex with the empress once a month. Every sexual encounter between the emperor and one of the members of the harem was recorded in lists. The emperor had to write down his partner for the night on a bamboo board that was presented to him by the chief eunuch at dinner. According to the law of the court it was forbidden for the emperor to sleep with one of his wives, so the women had to come to him. Legend has it that a woman, wrapped in silk, was carried to the emperor by a eunuch and had to return to the harem after intercourse, as she was not allowed to stay with the emperor. The Confucian rules also stipulated that the emperor must observe a three-year (according to Jung Chang two-year ) mourning period for his father Daoguang, who died in 1850 . During this time, no new women could be added to his harem. He also had to restrain himself sexually towards his existing wives: If he had become a father during this time, this would have been seen as such a lack of filial piety towards his father that, according to Confucian understanding, this would have called into question his ability as emperor. It was not until February 1853 that Emperor Xianfeng was able to have sexual contact with his wives again.

Each concubine had a small apartment, but only the empress was entitled to her own palace. There were strict rules in the harem, e. For example, it was prescribed what objects should be in the concubines' rooms, what clothes they should wear, and what food they should eat. Since Cixi belonged to the lowest-ranking group (levels six to eight), she was only entitled to 3 kg of meat per day. An empress, on the other hand, could use 13 kg of meat, a duck, a chicken, 12 jugs of water, 10 packets of tea, different types of vegetables and grains and the milk of 25 cows.

While the harem was actually only expanded in 1853 (or as early as 1852), Emperor Xianfeng violated the traditional rules insofar as he raised a concubine by the name of Zhen (貞 嬪, "purity") to the first rank of his empress among his wives . Like Cixi, she had come to court as a concubine, but was immediately raised to fifth rank. She was inconspicuous and sickly and that is why she was called the "fragile phoenix". As empress, Zhen had the important task of running the harem, which she performed masterfully, for under her leadership there was no malice or slander. Initially, there was nothing to suggest that Cixi was preferred as a concubine by the emperor and for two years he showed no sexual interest in her.

When her father fell ill during the Taiping Uprising in the summer of 1853 and died shortly afterwards, she was deeply touched and decided to make suggestions to the emperor for an appropriate response to the unrest. The emperor did not like this interference at all, since Cixi had violated a basic rule. He also expressed concern that she might interfere too much in state affairs after his death. A decree was drawn up providing for the elimination of the concubine should this situation arise. But he was later burned by Empress Zhen in the presence of Cixi. From this point on, the low-ranking concubine remained silent.

Li Fei (according to Jung Chang "a [.] Concubine") soon became pregnant and gave birth to a girl who, as such, had no influence on the dynastic line of succession. From the time when the pregnancy was established until 100 days after the birth, the emperor had to practice sexual abstinence from the pregnant woman. During this time he turned to other harem ladies and, among other things, had contact with the now twenty-year-old Cixi, who became the new favorite . She held this role until it became apparent in the late summer of 1855 that she was pregnant; from then on the emperor had to abstain from her.

Role as mother

On April 27, 1856, Cixi gave birth to her son Zaichun, who later became Emperor Tongzhi , in the New Summer Palace . He was to remain the only son of the emperor. In 1859 the favorite Li Fei gave birth to another son, but he lived only a short time.

The rank of official mother was not held by Cixi, but by Empress Ci'an (Zhen). Cixi was also not involved in raising the child, who was nursed by wet nurses and cared for by eunuchs. Contact between the birth mother and her son only existed on official occasions. Cixi later stated that this often led to arguments with the empress. At birth, however, the rank of Cixi within the palace hierarchy changed. Just like Li Fei after the birth of her daughter, Cixi was promoted to the rank of concubine of the first rank and was only subordinate to the Empress Ci'an (Zhen). The title she received with her exaltation was Yi Guifei (懿貴妃) or "Noble Imperial Wife Yi".

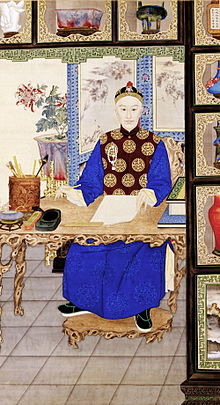

The rise within the palace hierarchy also meant for Cixi to be able to move into more spacious rooms. There, Cixi spent her time embroidering, playing with Pekingese , practicing traditional Chinese painting , or listening to the scholars at the Hanlin Academy , who were available to the harem members as tutors. The watercolors that have survived show that Cixi was a talented amateur painter. To what extent Cixi also dealt with current events is unknown.

The flight to Jehol

China at that time suffered a number of conflicts with Western powers . Great Britain, in particular, which emerged victorious from the Indian uprising in 1858 , pursued an aggressive gunboat policy to enforce its commercial interests in China: the proceeds from the Bengal- grown opium that was sold in China were necessary for British rule in India finance. This ultimately led to the Second Opium War . With the Treaty of Tianjin of 1858, Great Britain, France, Russia and the United States enforced

- the opening of further contract ports and,

- that the western powers could sell opium in China,

- that foreigners travel to the interior of the empire and

- that Protestant and Catholic clergy were allowed to do missionary work in the interior of the country.

The western allies attacked China again in 1860 for no reason. They suffered a defeat in front of the Taku Fortress , whereupon Lord Elgin sent a second punitive expedition to China in the summer of 1860. This conquered the fortress Taku, penetrated as far as Beijing , defeated a Mongolian army there and then looted the Old Summer Palace in the northwest of Beijing and burned it down.

The imperial court had after the defeat of the Mongol army at the gates of Beijing's hastily abandoned and the Summer Palace was the near the Great Wall located palace of Jehol fled. The refugees included the emperor and the empress Ci'an, Cixi, their now four-year-old son, Li Fei, the princes Yi and Cheng as well as the court official Sushun and a total of 6,000 eunuchs. Xianfeng's half-brother, Prince Gong , stayed behind in Beijing to negotiate with the Western allies. Emperor Xianfeng, on the other hand, did not face the conflict with the Western allies, but primarily sought distraction in drinking parties with members of the conservative gang of eight around court official Sushun and his favorite Li Fei. This was accompanied by increasing mental and physical decline. As before in Beijing, Cixi had no influence over the emperor and was generally not admitted to him. However, the historian Sterling Seagrave points to an event shortly after his arrival in Jehol that may have had a decisive influence on Cixi's actions after the emperor's death: By chance, one night Cixi witnessed the influential court official Sushun settling on the imperial throne and had his chief eunuch serve him a meal on imperial china . In several respects, this was such an extreme violation of the etiquette of the imperial court that Sushun risked his life, and a strong indication that Sushun probably planned to proclaim himself emperor after the death of the emperor either himself or as regent through a puppet ruler To exercise power. It seemed unlikely that Cixi's son was the puppet ruler planned by Sushun, since Sushun had already announced that Xianfeng had not chosen his son as heir to the throne. This meant that Cixi's life and that of her son were threatened.

The imperial succession

As a rule, the reigning emperor appointed one of his sons or - in exceptional cases - a nephew as his successor. The appointment of the heir to the throne did not have to be made by announcement. It was a tradition of the imperial court to keep the name of the designated successor in an always locked box. If, on the other hand, there was no designated successor, it was up to the Empress Dowager, in consultation with the most senior persons in the ruling house, to determine a suitable candidate.

Xianfeng's health had steadily deteriorated since arriving in Jehol. At the end of August 1861 he was so ill that his condition was considered critical. The dying emperor had already formed an eight-person Conservative Regency Council around the influential Sushun. No member of the Regency Council belonged to the direct imperial line, and all of the emperor's brothers had been passed over. Sushun had already given the order to open the sealed box in which the name of the heir to the throne should actually be deposited. It turned out to be empty in this case.

Cixi had repeatedly been denied access to the emperor on the grounds that the emperor was too ill to receive anyone other than his ministers. With her son in her arms, however, she managed to force her way into the imperial bedchamber on August 22, 1861, where numerous people from the court were gathered. There she called the dying emperor twice and held out his only son. With the assembled court as witnesses, the emperor orally appointed his son as his successor and the empress Ci'an and Cixi as regents a few minutes before his death.

Since so many court officials were present when Xianfeng appointed his son to be the next emperor, Sushun had to obey this decree. On the other hand, he initially ignored the appointment of Empress Ci'an and Empress Cixi as regents. The reason given to the court was that the appointment of the Regency Council was made with full consciousness, while the dying Emperor was no longer in his right mind when he appointed the Empress and Cixi as regents. Official documents of the palace show that Cixi then confidently confronted Sushun and initially enforced the appointment of Empress Dowager, which was due to her according to Chinese tradition. From August 23, 1861, she was equal in rank to the Dowager Empress Ci'an and now took the honorary name Cíxǐ ("Mercy of Joy"), by which she is known to this day. Cixi also ensured that both Ci'an and she each receive an imperial seal. Without the imprint of these two seals, no decree of the Regency Council was legally valid. The position of the isolated Jehol Empress widows was further strengthened when addressed to the Emperor memoranda of mandarin were addressed in the kingdom to these two. According to Confucian understanding, the empress widows were the guardians of the child emperor, the keepers of the imperial seal and the administrators of the state. With their letters, the military and civil servants made a record of their recognition of the authority of the two widows.

The two empress widows had an important supporter in Prince Gong , a half-brother of the emperor, whom Sushun was able to successfully keep away from Jehol during the emperor's illness. However, court etiquette required the prince to pay homage to the imperial corpse. During his visit to Jehol, Prince Gong managed to involve the two empress widows in his plan to overthrow Sushun. The fall of Sushun was initiated when high mandarins asked the two empress widows in memoranda to take over direct administration of the empire as regents instead of Sushun and his Regency Council and to be supported in their reign by one or two of the imperial princes. Sushun responded with a decree that rejected the two women 's rule. Both Cixi and Ci'an initially refused to seal this decree, which meant that it was not legally binding. Sushun finally enforced the sealing by the two empress widows by locking money that were necessary for the imperial court and locking the two empress widows with their entourage in the apartments, where they were so poorly taken care of that they became hungry and thirsty. Sushun presumably assumed that with this decree he had decided the power struggle for himself.

According to tradition, the young emperor had to arrive in Beijing before the funeral procession. This made it necessary for the court to return to Beijing in two separate processions , thereby creating the conditions for the widowed empress and the child emperor to evade Sushun's direct control. While Sushun and five other members of the Regency Council accompanied the coffin of the late emperor in the traditional funeral procession to Beijing, Cixi and Ci'an and two members of the Regency Council returned to Beijing together with the young emperor before the procession. Their military escort was headed by a general devoted to Prince Gong, who ensured that this part of the court only needed six days for the trip instead of ten and thus arrived in Beijing three days before Sushun. The very next day the two empress widows sealed a decree in the name of the child emperor, which ordered the arrest of the members of the Regency Council and declared the decree with which the Regency Council justified its appointment to be forgery. A cavalry force devoted to Prince Gong captured the regents. Sushun was first sentenced to death by a hundred cuts and then pardoned for beheading . Two high-ranking aristocrats on the Regency Council were forced to commit suicide; the others were denied their ranks and honors and were banished to remote places in the empire .

Regents

The long Chinese history shows only a few regents. One of the best known is Han Empress Lü Zhi , who lived around 185 BC. BC issued imperial edicts in his own name as well as Tang Empress Wu Zetian (625–705), who ruled partly behind the scenes and partly directly for forty years. Most regents only ruled for a short transitional period until the successor of a deceased emperor had reached a certain minimum age. Accordingly, the female members of an imperial harem did not acquire any experience that would have even remotely prepared them to act as regent. This also applies to Cixi and Ci'an. They also had little knowledge of events that took place outside the immediate palace area. The actual exercise of power was Prince Gong as a reigning prince regent, as such, also the Great Council chaired, and the six or seven ministers audience, recently headed gongs brother Prince Chun I. stood. The audience ministers had direct access to the young emperor and were considered to be those who could most easily influence the emperor and therefore held most of the power.

In 1872, Emperor Tongzhi was 16 years old enough to officially take over the business of government. Against his mother's wishes, he chose a close relative of the Empress Dowager Ci'an as his empress from among the young women proposed to him. However, the young emperor showed little interest or talent for politics. Instead of him, his mother as well as princes and officials took care of government. His attempt to dismiss Princes Gong and Chun in the fall of 1874 was prevented by the Empress widows. A little later the court announced that the emperor had contracted smallpox . The empress widows officially took over the government again. In January 1875, Cixi's son died, who was believed to have contracted syphilis in a brothel . He left no male heir. The empress died two months later.

The succession was again unregulated, as Tongzhi had not appointed a successor. The empress widows therefore had to choose a heir to the throne from among the imperial princes. Ultimately, Cixi prevailed and at the same time violated any old tradition. Instead of an older member of the imperial family, who actually had absolute priority, she appointed her underage nephew, son of her sister Rong with Prince Chun I, as emperor. With that she again made a child the "son of heaven" under the name Guangxu and again became ruler of the Middle Kingdom with the Empress Dowager Ci'an at her side. The latter, however, hardly played a role and left Cixi with practically unrestricted power as the “regent behind the curtain”. Ci'an died in 1881.

Reform and restoration

In the second half of the 19th century it became increasingly noticeable that China was lagging behind the West in economic, technological and military areas. In many cases, the population, but especially the intellectual elite, has called for appropriate reforms.

During her first reign, Cixi emphasized the superiority of China in ideological and moral matters and called for a reflection on its Confucian traditions (the so-called Tongzhi Restoration , named after the incumbent emperor). Nonetheless, by persuading her confidants, Prince Gong and Zeng Guofan, she slowly recognized the country's need to catch up in the practical field and thus the need for appropriate reforms (the so-called self-strengthening movement ). For example, the state leadership specifically promoted the study of foreign cultures, languages and technologies, in particular by founding appropriate technical schools in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou , but also by sending young Chinese to study abroad. In addition, the first shipyards, arsenals and arms factories were built in the provinces of Jiangsu and Fujian . The first Chinese steamship was launched in Mawei in 1868, and the first Chinese steamship company was founded in 1872.

From the second reign, however, Cixi's willingness to reform gave way to a downright reactionary, stubborn conservatism, which can possibly be explained by the death of her close adviser Zeng in 1872. She fell out with Prince Gong because he advised against building the new summer palace. Cixi did not find any connection with the new generation of reformers, instead they gathered around the young emperor Guangxu. He had come of age in 1889, whereupon Cixi largely withdrew from politics. The emperor was deeply impressed by the Meiji Restoration in Japan and tried to copy it for his country. With the advice of capable court officials, led by Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao , in 1898 he launched a large-scale reform program (the so-called Hundred-Day Reform ). He wanted to bring about a fundamental revision of the traditional, Confucian-influenced structures of his country. But he underestimated the resistance of the conservative ruling classes, who saw the reform program as a threat to their position. They intervened at Cixi and told her that the reforms would do serious damage to the empire and the dynasty. Ultimately, she believed those who refused to reform and took action against the emperor's reform policy, which turned out to be fatal for the future of the country and the imperial family. With the support of the military commander Yuan Shikai , she usurped power like a coup d'état , placed her nephew under house arrest and effectively took over the reign for the third time.

It was only after the Boxer Rebellion was put down by the foreign powers that Cixi realized how profoundly necessary a modernization of China based on the Western model was: From 1903 onwards, it began cautiously with reforms in the economic field (establishment of a trade ministry, reform of the customs administration), the legal system (abolition of torture and execution by dismemberment) and education (introduction of exams in history, geography and science; abolition of the old-style civil servant exams ). For 1917 it even announced the introduction of a constitutional monarchy based on the European model. Of course, this could no longer stop the fall of the Qing dynasty. The reforms came far too late, and the people had almost completely lost confidence in the Qing government. The foundations for the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 were inevitable. Cixi did not experience this anymore; she died on November 15, 1908.

Domestic political unrest

Cixi's entire period of activity was marked by considerable domestic political unrest: the Taiping uprising was finally put down with the conquest of Nanjing by government troops in 1864. In 1866 a certain Jakub Bek took advantage of the Dungan uprisings in Chinese Turkestan to set up a regime called Jetti-Shahr . It could not be eliminated until 1877 by General Zuo Zongtang ; five years later, the area was given the status of an autonomous region under the name of Xinjiang . There were also popular uprisings in several provinces, around 1865 in Gansu .

While Cixis third reign came to protest the increasingly reactionary policy nationwide to subversive activities of several secret societies (for example, "pugilists of Law and Unity"), traditionally simplistic are summarized in the West as "boxer". Cixi succeeded in redirecting this aggression, valid for her dynasty, to the foreign powers, which in 1900 led to the Boxer Rebellion . The boxers smashed foreign machines and technical equipment due to widespread unemployment through imported goods. On January 11, 1900, the Empress allowed the boxer movement, which had already spread to the capital: when peaceful and law-abiding people practice their mechanical skills in order to support themselves and their families, this is in line with the principle: “Be careful be and help each other. ” On June 19, 1900, following a fake dispatch, she offered a bounty on every stranger killed, regardless of whether they were men, women or children. Your troops took part in the siege of the Legation Quarter . This would have resulted in a massacre of those trapped had the influential General Ronglu not disapproved of the procedure and therefore refused to surrender the artillery. When the European relief troops reached the imperial capital on August 14, 1900, Cixi fled with her court, disguised as ordinary people, from the city to the protection of the Manchurian garrison from Xi'an to central China.

On January 7, 1902, she returned to Beijing as regent after Viceroy Li Hongzhang had reached an agreement with the Europeans on how to proceed. Now she changed the political side and distanced herself from the boxers. They ordered their leaders and the so-called "iron hats" to be punished, i. H. the anti-European and war-ready Manchu elite.

Given the obvious military weakness and the dangerousness of any modernization for the dynasty, and despite the oppressive debts due to the Boxer Protocol , Cixi now used all available means to at least restore the imperial splendor. So the New Summer Palace was rebuilt, which had been destroyed by the European powers as a punitive measure on the occasion of the Boxer uprising. To do this, however, they used funds that were actually intended for the reconstruction of a modern war fleet . This misappropriation further weakened China's military clout at sea.

Relationship to foreign powers

During the time of Cixi, the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and western states, forced by the Treaty of Tianjin of 1858, and the establishment of the Chinese foreign office, the Zongli Yamen, fell . After the foreign powers had opened representations in Beijing in 1860, the first Chinese embassy in Europe was founded in London on January 21, 1877 . The German Empire and Japan followed in the same year, Russia and the USA in 1878 , France in 1895 , and finally Italy , Austria , Belgium and the Netherlands in 1902 .

However, this should not hide the fact that the foreign powers have stepped up their annexation efforts in China. At first all vassal states were lost step by step: In 1885 Annam (Vietnam) had to be ceded to France, and a year later Burma to England. After the first Sino-Japanese War 1894–1895, Korea , which had had the status of a “Common Area of Interest” since 1886 , fell to Japan together with Taiwan and the Pescadores Islands . In addition, the island empire had to pay “war compensation” of 200 million silver dollars, four more ports had to be opened and industrial activity had to be allowed in China.

From 1897 onwards, several European countries forced China to "lease" areas, which then received semi-colonial status with extensive mining and railway rights for foreign powers: Qingdao (German Empire), Port Arthur (Russia), Weihai (England), Guangzhouwan (France) . In addition, the Yangtze Valley was claimed by England as a "sphere of interest", parts of southern China by France and Manchuria by Russia and Japan. The foreign domination reached a climax in the brutal suppression of the Boxer Rebellion .

Cixi's end

On November 15, 1908, Cixi died of influenza . Before that, she and Puyi had chosen a child to succeed her to the dragon throne for the third time. The childless Emperor Guangxu had died a day before her under completely unexplained circumstances. Whether he was really killed by one of her followers or even on her orders can only be guessed. However, recent chemical analyzes have shown arsenic poisoning . Cixi probably wanted to protect the position of her favorites by appointing a new child emperor, but this only led to a further weakening of the imperial government. The position of Prince Regent Chun II , the father of Puyi, was rather weak, so that he could not advance the reforms and gradually lost control of the empire.

Cixi was buried in the Dingdongling Mausoleum she built in the Eastern Qing Tombs . Her deaths did not last long, however, because as early as 1928 Kuomintang troops looted the grave and desecrated her body. The jewels and pearls she carried were reportedly presented as a trophy to Chiang Kai-shek's wife, Song Meiling .

Historical evaluation

Cixi is often portrayed as tough, domineering and sometimes cruel. However, there are also reports that characterize them as charismatic and considerate. Largely undisputed, she had a political instinct to stay in power and used every avenue to lead her interests to victory. In the opinion of Sterling Seagrave, the establishment of her son as the new emperor and the reign of her and the dowager empress Ci'an in the face of palace intrigues by courtiers and Manchurian nobles was brave for the then young, inexperienced woman. Without these qualities, it would not have been able to hold power for 47 years. Furthermore, many of their decisions are against the background of ongoing power struggles between conservatives and reformers behind the courtly scenes and, more often, to consider foreign interference that adversely affects the Qing emperor's authority with the Chinese people. It was successful in integrating the Manchurians and Mongols into the state and in suppressing revolts (especially in East Turkestan ), but not in containing European and Japanese attacks.

The image of the cruel, power-hungry woman guided by strong sexual instincts was mainly promoted in Great Britain . In particular, the British Beijing correspondent for the London Times , George Morrison, described Cixi in his articles as a monster and an assassin . Today it is known that Morrison fell for statements from supposedly "intimate connoisseurs of the Chinese court" (above all Edmund Backhouse and the exiled Kang Youwei ) and that his articles corresponded more to the fantasies and expectations of puritanically oriented British. Today, therefore, the view is also taken that Cixi, during the time of her cohabitation and her reign, hardly left the area around the Forbidden City and knew life outside largely only from hearsay, from conservative advisers close to her to the aristocracy with incorrect news about her sometimes not very clever Decisions was made. Through these misjudgments, she is complicit in the fall of the Chinese Empire . Instead of relying on an experienced and reform-minded prince as emperor early on, she repeatedly enthroned weak child emperors in order to secure her own position. The appointment of Puyi was such a momentous act after her death, as she did not comply with political necessities in favor of an imperial nepotism . The Chinese monarchy might have continued to exist if Cixi had faced China's problems with other approaches. On the other hand, the dowager empress fought for her survival as a woman in a patriarchal system of rule and was quite willing to renew the country and pursue political reforms.

From a cultural point of view, Cixi has rebuilt the New Summer Palace twice as a historically significant symbol of imperial splendor and Chinese horticulture , even if naval funds were used for this and this reconstruction was seen by many Europeans as a sign of degeneration at the time. Overall, their life performance is rated highly ambivalent.

Gallery - Cixi as a painter

literature

Secondary literature

- Albert Brüschweiler: The funeral of the Empress widow of China . In: Schweizer Illustrierte , Vol. 14. 1910, pp. 113–117. ( e-periodica )

- Feng Chen-Schrader: The Discovery of the West. China's first ambassador to Europe 1866–1894 (= Fischer pocket books 60165 European history ). Translated from the French by Fred E. Schrader. Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-596-60165-7 .

- Wolfram Eberhard : History of China. From the beginnings to the present (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 413). 3rd, expanded edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1980, ISBN 3-520-41303-5 .

- John King Fairbank : History of Modern China. 1800–1985 ( dtv 4497). (Original title: The Great Chinese Revolution. ). Translated by Walter Theimer. Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-423-04497-7 (2nd edition, 9th – 12th thousand. Ibid 1991).

- Jacques Gernet : The Chinese World. The history of China from its beginnings to the present (= Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch. Vol. 1505). 1st edition, reprint. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1997, ISBN 3-518-38005-2

- Gisela Gottschalk : China's great emperor. Their history - their culture - their achievements. The Chinese ruling dynasties in pictures, reports, etc. Documents. Pawlak, Herrsching 1985, ISBN 3-88199-229-4 .

- Margareta Grieszler: The last dynastic funeral. Chinese funeral ceremony for the death of the Dowager Empress Cixi. A study (= Munich East Asian Studies. Vol. 57). Steiner, Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-515-05994-6 .

- Manfred Just: The Empress-Widow Cixi. Duncker and Humblot, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-428-08981-2 .

- Sterling Seagrave : The Concubine on the Dragon Throne. Life and legend of the last Empress of China 1835–1908 (= Heyne 01 General series 9388). Heyne, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-453-08202-8 .

- Jonathan D. Spence : China's Path to Modernity. Hanser, Munich et al. 2001, ISBN 3-446-16284-4 .

- Marina Warner : The Empress on the Dragon Throne. The life and world of the Chinese dowager empress Tz'u-hsi. 1835-1908. Ploetz, Würzburg 1974, ISBN 3-87640-061-9 .

Novels concerning Cixi

- Pearl S. Buck : The Girl Orchid . Roman (= Ullstein book 23238). New edition, paperback edition. Ullstein, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1994, ISBN 3-548-23238-8 .

- Anchee Min : The Last Empress. Novel. Krüger, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-8105-1278-8 .

- Anchee Min: The Empress on the Dragon Throne. Novel. Krüger, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-8105-1283-3 .

- Hans D. Schreeb: Behind the walls of Beijing. Roman (= Ullstein 25039). Ullstein, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-548-25039-4 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Cixi in the catalog of the German National Library

- WG Sebald to Tz'u Hsi

Individual evidence

- ^ Hugh Trevor-Roper : Hermit of Peking. The Hidden Life of Sir Edmund Backhouse. Knopf, New York NY 1977, ISBN 0-394-41104-8 .

- ^ Seagrave: p. 40.

- ↑ Chang, Jung, 1952-: Empress Widow Cixi: the concubine who paved China's way into the modern age . 1st edition. Blessing, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-89667-418-0 , pp. 22 & 24 .

- ↑ Chang, Jung, 1952-: Empress Widow Cixi: the concubine who paved China's way into the modern age . 1st edition. Blessing, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-89667-418-0 , pp. 19 .

- ↑ Chang, Jung, 1952-: Empress Widow Cixi: the concubine who paved China's way into the modern age . 1st edition Blessing, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-89667-418-0 , pp. 19-22 .

- ^ Warner: p. 16.

- ↑ Chang, Jung, 1952-: Empress Widow Cixi: the concubine who paved China's way into the modern age . 1st edition. Blessing, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-89667-418-0 , pp. 22-23 .

- ↑ Chang, Jung, 1952-: Empress Widow Cixi: the concubine who paved China's way into the modern age . 1st edition. Blessing, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-89667-418-0 , pp. 23-24 .

- ↑ Jung Chang, Empress Dowager Cixi, p. 24

- ↑ Chang, Jung, 1952-: Empress Widow Cixi: the concubine who paved China's way into the modern age . 1st edition Blessing, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-89667-418-0 , pp. 24-25 .

- ↑ Chang, Jung, 1952-: Empress Widow Cixi: the concubine who paved China's way into the modern age . 1st edition. Blessing, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-89667-418-0 , pp. 25-26 .

- ↑ a b Seagrave: p. 56.

- ^ Seagrave: p. 57.

- ↑ Chang, Jung, 1952-: Empress Widow Cixi: the concubine who paved China's way into the modern age . 1st edition. Blessing, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-89667-418-0 , pp. 26-28 .

- ^ Warner: p. 29.

- ↑ Empress Widow Cixi, 2004, p. 28

- ↑ Chang, Jung, 1952-: Empress Widow Cixi: the concubine who paved China's way into the modern age . 1st edition Blessing, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-89667-418-0 , pp. 29 .

- ↑ a b c d Chang, Jung, 1952-: Empress Dowager Cixi: the concubine who paved China's way into the modern age . 1st edition Blessing, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-89667-418-0 , pp. 30 .

- ↑ a b Seagrave: p. 58f.

- ↑ Chang, Jung, 1952-: Empress Widow Cixi: the concubine who paved China's way into the modern age . 1st edition Blessing, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-89667-418-0 , pp. 35 .

- ↑ a b Chang, Jung, 1952-: Empress Dowager Cixi: the concubine who paved China's way into the modern age . 1st edition Blessing, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-89667-418-0 , pp. 31 f .

- ^ Seagrave: p. 54.

- ↑ Chang, Jung, 1952-: Empress Widow Cixi: the concubine who paved China's way into the modern age . 1st edition Blessing, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-89667-418-0 , pp. 30-31 .

- ↑ a b Seagrave: pp. 62-63.

- ↑ Chang, Jung, 1952-: Empress Widow Cixi: the concubine who paved China's way into the modern age . 1st edition Blessing, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-89667-418-0 , pp. 34 f .

- ↑ Chang, Jung, 1952-: Empress Widow Cixi: the concubine who paved China's way into the modern age . 1st edition Blessing, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-89667-418-0 , pp. 37 .

- ^ Seagrave: p. 64.

- ↑ Warner: p. 42f.

- ^ Seagrave: p. 68.

- ^ Seagrave: p. 69.

- ^ Niall Ferguson : Empire. How Britain made the modern world. Penguin Books, London et al. 2004, ISBN 0-14-100754-0 , p. 166.

- ^ Seagrave: p. 88.

- ^ Seagrave: p. 95.

- ↑ Seagrave: p. 96f.

- ^ Seagrave: p. 106.

- ^ Warner: p. 80.

- ^ Seagrave: p. 104.

- ↑ a b Warner: p. 84.

- ^ Seagrave: p. 107ff.

- ^ Seagrave: p. 108.

- ↑ Seagrave: p. 113f.

- ^ Warner: p. 85.

- ^ Seagrave: p. 116.

- ↑ New York Times assessment of March 29, 1868, quoted in Seagrave, p. 133.

- ↑ Spence: p. 269ff.

- ↑ Spence: p. 278ff.

- ↑ Spence: pp. 305ff.

- ↑ Spence: p. 290ff.

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/04/world/asia/04iht-emperor.1.17508162.html - New York Times, Arsenic killed Qing emperor

- ↑ Spence: p. 325ff.

- ^ Seagrave: p. 17.

- ↑ An example of this is the travelogue of: Katherine A. Carl: With the Empress Dowager of China. Nash, London et al. 1906 (numerous issues).

- ^ Seagrave: p. 138.

- ^ Seagrave: p. 24.

- ^ Seagrave: p. 213.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Cixi |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Cíxǐ |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Chinese concubine of the Manchu emperor Xianfeng and empress mother |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 29, 1835 |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 15, 1908 |

| Place of death | Beijing |