Liang Qichao

Liang Qichao (Liáng Qǐchāo; Chinese 梁啟超 ; legal age Zhuórú 卓 如 ; pseudonym Réngōng 任 公 ; born February 23, 1873 in Xinhui , Guangdong ; † January 19, 1929 in Beijing ) was a Chinese scholar, journalist , philosopher and reformer during the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), which belonged to a new generation of intellectuals formed after the Opium War , and who inspired other Chinese scholars with their reformist movements.

Short biography

Liang Qichao was born on February 23, 1873 in a small village in Xinhui (新 會), Guangdong Province .

As the son of a farmer, he would normally have been denied education, but his father Liang Baoying (梁寶瑛, adult name Lianjian 蓮 澗) taught him as best he could from the age of six and introduced him to various literary works.

Liang has been married twice, to Li Huixian (李惠 仙) and Wang Guiquan (王桂荃). The marriages produced nine children, all of whom were successful. Three of his children later joined the scientific staff at the Chinese Academy of Natural Sciences .

Early life

At the age of 11, Liang passed the Xiucai (秀才), a low-level final exam, and then took on the arduous task of studying for the traditional state exam in 1884 . Then at age 16 he passed the Juren (舉人), a slightly more sophisticated audit, and was the youngest successful participants this time.

In 1890 he broke with the traditional educational path, failed his Jinshi (進士), the national final examination in Beijing , and never achieved a higher degree. He was inspired by the book Information About The Globe (瀛 環 志 略) and developed a keen interest in Western ideologies . After returning to his homeland from Beijing, he began to research and study as a student of Kang Youwei , a famous scholar and reformist who taught at Wanmu Caotang (萬 木 草堂). His teacher's teachings on foreign affairs increased Liang's interest in reforming China .

With Kang, Liang went to Beijing again in 1895 to catch up on the state exam, but failed a second time. Nevertheless, he stayed in Beijing afterwards and helped Kang disseminate Domestic and Foreign Information . He also helped organize the National Reinforcement Society (強 學會), where he served as secretary.

The reforms of 1898

As an advocate of the constitutional monarchy , Liang was not satisfied with the way the Qing rulers governed and wanted to change the state of affairs in China. He initiated reforms with Kang Youwei (康有為, 1858–1927). They wrote a petition to the throne, which Emperor Guangxu (光緒 帝, 1871–1908, ruled from 1875–1908) took up and resulted in a reform program. This movement is known as the Wuxu Reform, or the Hundred Day Reform . They were of the opinion that China needed self-strengthening and called for many intellectual and institutional changes, including the fight against corruption and restructuring of the state examination system and the establishment of a national education system.

The resistance of conservative forces was awakened by Guangxu's zeal for reform, and Liang (who did not work in an exposed position at all, but only held a middle official rank) was ordered by the aunt of the Guangxu emperor Cixi (慈禧太后, 1835-1908), was the leader of the politically conservative party and later regent again, should be arrested. Liang managed to escape the Cixi captors. Her power base was threatened by Guangxu's Hundred Day Reform, and she felt it was too radical. It was not until the beginning of the 20th century that Cixi set in motion a reform program that wanted to implement many of the changes that had previously stalled her.

The conservative coup ended all reforms in 1898, Liang was by Japan into exile banished, where he spent the next 14 years of his life. However, this did not prevent him from actively defending democracy and reforms and used his writings to strengthen the support of the reformers, which met the open ears of the Chinese overseas and also of his own government.

In 1899 Liang traveled to Canada , where he was among others Dr. Sun met Yat-sen and continued his journey through Honolulu and Hawaii . During the " Boxer Revolution " Liang stayed in Canada, which he used to formulate " Society for the Rescue of the Emperor " (保皇 會).

From 1900 to 1901, Liang visited Australia on a 6-month tour, the aim of which was to gain more supporters for a campaign to bring the Chinese Empire up to date by bringing China the best of Western technologies, their industries and State system.

In 1903, Liang made an eight-month tour of the United States as a lecturer , which included a meeting with President Theodore Roosevelt in Washington, DC . He then returned to Japan via Vancouver , Canada.

Claims to journalism

As a journalist

Liang was once described by Lin Yutang (iang) as "the greatest figure in the history of Chinese journalism," while Joseph Levenson , author of Liang Ch'i-ch'ao and the Mind of Modern China , described Liang as a brilliant scholar, journalist and political figure described.

Liang Qichao was "the most influential scholar and journalist of the turn of the century," according to Levenson. Liang showed that newspapers and magazines can be used as an effective medium for communicating political ideas.

Liang, seen as a historian and journalist, believed, and also publicly proclaimed this view, that these two professions must have the same purpose and moral commitment. "By examining the past and revealing the future, I will show the people of the nation the path of progress." He then founded his first newspaper, Qingyi Bao (清 議 報), which was named after a student movement of the Han Dynasty .

Exile in Japan enabled Liang to speak freely and exercise his intellectual autonomy . In the course of his career in journalism, he designed first newspapers, such as Zhongwai Gongbao (中外 公報) and Shiwu Bao (時務 報). He also published his moral and political ideas in Qingyi Bao (清 議 報) and The New Citizen (新民 叢 報).

In addition, he spread his views on republicanism through his literary works in China and around the world. Accordingly, he became an influential journalist in some areas of political and cultural aspects and began to write new forms of periodical journals. So his way of expressing his patriotism was paved by journalism.

Commitment to the principles of journalism

One way to put Liang's journalistic work in the spotlight is to consider whether his work contains the elements of journalism, as described in Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel's book The Elements of Journalism . Even though it was not published until 72 years after Liang's death, this book is still a helpful tool in determining what kind of journalist Liang is because, as the book's introduction says, the same major news items remain as they did at the time .

"Journalism's first obligation is the truth"

The kind of truth Liang dedicated himself to bringing his readers closer was more ideological than factual. His magazine "New Citizen", for which Liang was editor-in-chief, was one of the first publications of its kind. Instead of simple reports, Liang brought relevant new ideas and insights and spread his view of democracy, republicanism and rule through his in his newspapers Readership both in China and overseas. For most of his readers, his ideas were brand new. And while democracy and republicanism are not truths in the conventional sense of the word, Liang truly believes that they are the best system for ruling China. His commitment to bringing these ideas closer to citizens explains why Liang's work includes the first element of journalism.

"The first loyalty of journalism belongs to the citizens"

Liang made the claim that a newspaper is "the mirror of society," "the livelihood of the present," and "the illumination of the future." He categorized newspapers by four types:

- an individual's newspaper,

- Newspaper of a party,

- Newspaper of a nation and

- Newspaper of the world.

Ultimately, his aim was to produce a newspaper for the world and he said that "a newspaper serves the world in the interests of humanity ".

In his manifesto, The New Citizen , one can see that Liang was a defender of democracy and republicanism. The focus of his publications was on educating his readers about the empowerment of citizens through his political ideas. His writings and work had a large audience and helped educate readers in ideas that they could not discover for themselves. There was much to suggest that Liang sought to provide citizens with the information they needed to be free and self-governing, which is exactly what Kovach and Rosenstiel named as the primary purpose of journalism.

"Its practitioners must retain independence from their publications"

Liang once declared, “How great is the power of the newspaper. And how serious is the duty of the newspaper! ”Liang also believed that freedom of conscience, freedom of expression, and freedom of the press were the mother of all civilization .

Liang was exiled to Japan because he was very critical of the Qing Dynasty during the WuXu reform . Nevertheless, he did not let himself be stopped from writing more articles and essays on the political changes China needs. He withstood the political pressure and still held against the Qing Dynasty, which is why he preferred exile to the robbery of literary and political freedom. Because of his exile, Liang remained independent from the Qing government, which he often wrote about. It was precisely this independence from those who wished to be able to oppress him, such as the imperial aunt Cixi, that allowed him to freely express his views and ideas about the political situation in China.

The Journal Renewing Citizens ( Xinmin Congbao 新民叢 報)

Liang produced a journal called Renewing the Citizen ( Xinmin Congbao 新民叢 報) which was published every fortnight and was widely used. It was first published in Yokohama , Japan on February 8, 1902.

The journal covered a wide variety of topics including politics, religion, law, household and economics , business , geography, and current and international affairs. In this journal, Liang coined many Chinese equivalents of "never-heard-theories" or "expressions" and he used the magazine to spread popular opinion even to distant readers. Liang hoped that through the news, analysis and essays New Citizen could begin a new chapter in Chinese newspaper history.

A year later, Liang and his staff saw a change in the newspaper industry and noted that "since we launched our journal five years ago, there have been nearly ten more separate journals with the same style and design."

As editor-in-chief of New Citizen magazine , Liang was able to distribute his writings. The journal was published unhindered for five years and only ended in 1907 after 96 issues. At that time the readership was estimated at 200,000.

The role of the newspaper

As one of the pioneers of Chinese journalism of the time, Liang believed in the strength and power of the newspaper, especially in its influence on government policy.

Using the newspaper to convey political ideas: Liang recognized the importance of the social role of journalism and, prior to the May Fourth Movement (also known as the "New Culture Movement"), developed the idea of a strong relationship between politics and journalism . He believed that newspapers and magazines should serve as a necessary and effective tool for conveying political ideas. He also believed that newspapers should not only act as the record of history, but that they could help shape the course of history.

Press as a weapon in the revolution: Liang also thought that the press was an effective weapon in serving the national uprising. After Liang's words, the newspaper is "a revolution of the ink, not a revolution of the blood." He went on to write that "the newspaper recommends its government to the government as a father or older brother does to a son or younger brother - teaches him when he doesn't understand and reprimands him when he does something wrong." Undoubtedly, his undertaking to unite and dominate a rapidly growing and highly competitive press market set the tone, also for the first generation of newspaper historians of the "May Fourth Movement".

The newspaper as an educational program: It was in Liang's awareness that the newspaper could serve as an "educational program" and so he said that he "collects all the thoughts and expressions of the nation and systematically demonstrates them to citizens, irrelevant whether they are important or not , precise or not, radical or not. Therefore, the press can contain everything, reject and produce, but just as destroy it. "

For example, during his most radical phase, Liang wrote a well-known essay entitled " The Young China " and published it in his Qing Yi Bao (清 議 報) magazine on February 2, 1900. It was through this essay that the concept of the unitary state was established and included it has been argued that the young revolutionaries hold the future of China. This essay was very influential on Chinese political culture during the "May Fourth Revolution" in 1920.

Unstable press: Liang thought that the press was experiencing considerable unsteadiness at the time, not only because of the lack of financial resources and conventional social prejudice, but also because of the social atmosphere that was not favorable to recruiting there was a lack of roads and highways, which made it more difficult to deliver newspapers. Liang made the statement that the popular newspaper is nothing more than a mass of commodities, and that these newspapers do not have the slightest influence on the nation as a society, which he strongly criticized.

Literary career

Liang was not only a traditional Confucian scholar, but also a reformer. He contributed to the reform of the late Qing by trying to interpret non-Chinese ideas of history and the state government in various articles to stimulate the Chinese consciences of citizens and to build a new China. In his writings, for example, he argued that while China should protect the ancient teachings of Confucius , it should also learn from the success of Western political life and not just adopt Western technologies. Therefore he was seen as a pioneer of political friction.

Liang shaped the idea of democracy in China and used his writings as a medium to combine Western science methods and traditional history studies. His work was strongly influenced by the Japanese political scholar Katō Hiroyuki (加藤 弘 之, 1836-1916), who used methods of social Darwinism to promote the extras ideology in Japanese society. Liang distinguished himself through much of his work and subsequent influence on the Korean nationalists in the 19th century.

1911–1927: politician and scholar

With his writings, Liang Qichao had made a significant contribution to the spread of ideas such as popular sovereignty (minquan) or nation (minzu) in China. He himself had thus trained the generation of revolutionaries. When the revolution finally broke out, he was initially skeptical of it, but then quickly came to terms with it. Because of its great reputation, various groups sought its support. Liang founds several parties himself, but also let Yuan Shikai pull him over to his side, which, according to Meng Qiangcai, his mainland Chinese biographer, made him a "maid". Liang promised himself an "enlightened dictatorship" (kaiming zhuanzhi) from Yuan, which would bring about a modernization of China. However, Yuan Shikai had no primary interest in this, but intended to rise to the rank of emperor (ironically, under the government motto "Hongxian", i.e. the sublime constitution). When Liang saw what was going on, he immediately gave up his support and henceforth worked in favor of the opposition Republicans in southern China. Yuan Shikai's death put an end to the ghost, but at the same time it was the signal of the period of the warlords, who divided China into individual zones of influence in which they controlled and reigned. Liang abstained from politics, but was committed to a declaration of war on the German Reich and thus to entry into the First World War, which he succeeded in 1917. In China there were high hopes that at least some of the "unequal treaties" could be repealed. However, the western powers had already concluded secret treaties with Japan in which they passed on the formerly German privileges (in Qingdao / Tsingtau and in Shandong Province) to it. Liang contributed to the outbreak of the May Fourth Movement by sending a telegram to China. The telegram was released, which started the student protests.

- Travel to Europe 1919–1920

Liang took part in the Versailles peace negotiations as an unofficial delegate. There he became aware of the real bargaining for countries and people. In his "Impressions of a European trip", published after his return in 1920, he paints a gloomy picture of Europe and at the same time pleads for a conscious fusion of Eastern personalized ethics and Western science and thoroughness. Here he presents the old ideas of the Confucian classic Daxue ("Great Teaching") in a modern look. After his return from Europe, Liang pursues almost exclusively academic activities. He teaches u. a. at Nankai University in Tianjin.

- Science and Metaphysics (1923)

One last time Liang Qichao joins a current debate: The debate about "Science and Metaphysics" (科學 與 玄學, kexue yu xuanxue) from 1923. This was shaped by two of his students who followed him three years earlier Traveled to Europe: Zhang Junmai (alias Zhang Jiasen, alias Carsun Chang, 1887–1969) and Ding Wenjiang. It was about the question of whether and to what extent science can be a view of life. Liang regarded himself as "neutral", he accused the two main competitors of not having argued precisely enough, but ultimately took the position that although life is very much determined by science, it can only explain the rational aspects of being, but not the irrational ones, such as B. love. “Where life is subject to the aspects of reason (lizhi), it can be explained with scientific methods. As far as the emotional side is concerned, life goes absolutely beyond science, ”he writes in his post" Life View and Science "(人生觀 與 科學, Renshengguan yu kexue).

- death

Liang's late years were not comfortable because of a kidney disease. He had to go to hospital several times between 1926 and 1928. In 1927 he had to give the last escort to Kang Youwei, from whom he had long since separated spiritually, but whom he had always understood as his teacher . Liang died on January 19, 1929 in the Union Medical College Hospital (協和 醫院, Xiehe Yiyuan) in Beijing.

Historiographical thoughts

Liang Qichao's historiographical thoughts represent the beginning of modern Chinese historiography and illustrate some important directions of Chinese historiography in the 20th century.

The main mistake of " ancient historians " (舊 史家) for Liang was the lack of a requirement for a national consciousness for a strong and modern nation. His call for a new history went beyond a new orientation of historical writings in China, for a rise in modern historical consciousness was also evident among Chinese intellectuals.

The people, too, began to form their own opinion, despite struggles and party differences, which Liang summarized in two core theses:

- No one who is not Chinese has the right to interfere in Chinese affairs.

- Everyone who is Chinese has the right to meddle in Chinese affairs.

He went on to say that the first sentence speaks to the spirit of the national state, while the second speaks to the spirit of the republic .

During this period of Japanese competition in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–95), Liang was present in protests in Beijing urging the Chinese people to participate in the rule. This protest was the first of its kind in Chinese history. The historiographical revolution (史學 革命) introduced by Liang Qichao in the early twentieth century also showed the changing outlook on tradition. Frustrated by the failure of his reforms, Liang embarked on cultural reform. In 1902, while in exile in Japan, Liang wrote New History (新 史學) and thus began to attack traditional historiography.

translator

Liang was the head of a translation company overseeing the training of students who were learning to translate Western works into Chinese. He believed that this task was the most essential of all essential companies ready to be carried out , because he also believed that Western people would be successful - politically, technologically and economically. However, Liang could not speak any foreign languages, only read some Japanese.

Philosophical work: After the rescue from Beijing and the government raid on the anti-Qing Protestants, Liang studied the work of Western philosophers of the Enlightenment period , such as B. Hobbes , Rousseau , Locke , Hume and Bentham , which he reproduced and commented on in his newspapers and magazines. He is thus in the tradition of Yan Fu (with whom Liang was friends), who made the most important of these works known in Chinese translations, but seldom translated them literally, but took over theses from the respective works and provided them with his own interpretation. Liang's essays were published in a variety of magazines and newspapers (which he himself edited) and an interest among Chinese intellectuals was evident, creating a new spiritual flowering and diversity.

Western social and political theories: In the early 20th century, Liang played a significant role beyond the borders of China in introducing Western social and political theories as well as social Darwinism and international law, e.g. B. in Korea . Liang wrote in his well-known manifesto The New Citizen (新民 說):

Freedom means freedom of the group, not freedom of an individual. (...) Men are not allowed to be slaves of other men, but they have to be slaves of their group. So, if they are not slaves to their own group, they will be slaves to another.

Poet and novelist

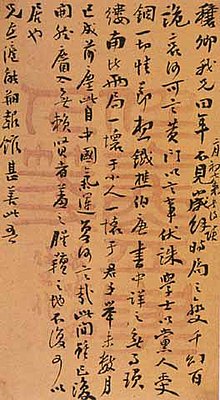

Liang managed the reform in the two genres of poetry and novel. Yinbingshi Heji《飲冰 室 合集》 (Collected Works from the Chamber of the Ice Drinker) are representative literary works that have been collected and edited in 148 editions.

He got the idea to call his work Collected Works from the Chamber of the Ice Drinker from a sentence in a passage written by Zhuangzi (《莊子 • 人間 世》), which says: "Although I am grieved and cold for reasons because of my involvement in politics, my heart is still warm and eager to continue my work. " (“吾 朝 受命 而 夕 飲 冰 , 我 其 內熱 與”) As a result, Liang called his workplace Yinbingshi and described himself as Yinbingshi Zhuren ( 飲冰 室 主人), which literally means “host of the ice drinker's chamber” . In doing so, he demonstrated his idea that he would be angry about all political matters, but nevertheless, or even because of it, try his best to reform society through the effort of writing.

Liang also wrote fictions such as Fleeing to Japan after the failure of the “Hundred-Day Reform” (1898) or About the relationship between fiction and the administration of the people (論 小說 與 群 治 之 關係, 1902). These novels highlighted the modern age of the West and called for reform.

Teacher

Liang resigned from politics and teaching at Tung-nan University in Shanghai and as a tutor at Tsinghua University in Beijing in the late 1920s . He founded Jiangxue She (Chinese Lecture Association) and, besides Driesch and Tagore, brought many intellectual people to China. Academically, he was a renowned scholar of the time who introduced Western learning and ideologies, but also made extensive studies of ancient Chinese culture.

During the last decade of his life, he also wrote many books documenting Chinese cultural history, Chinese literary history and historiography. He also had a strong interest in Buddhism and wrote numerous historical and political articles with Buddhist influence. Furthermore, while he was always expanding his own collection of articles, he also influenced students in the production of their own literary works. Liang's students included Xu Zhimo , a renowned modern poet, and Wang Li , founder of Chinese linguistics as a modern branch of knowledge and teaching.

Publications

- Overview of Science in the Qing Period (清代 學術 概論, 1920)

- The doctrine of Moism (墨子 學 案, 1921)

- The history of science in China over the past 300 years (中國 近三 百年 學術 史, 1924)

- History of Chinese Culture (中國 文化史, 1927)

- The Construction of New China

- The teaching of Laozi (老子 哲學)

- History of Chinese Buddhism (中國 佛教 史)

- Collected works from the ice drinker's chamber 饮 冰 室 合集. Shanghai: Zhonghua Shuju, 1936.

- Collected works from the chamber of the ice drinker 饮 冰 室 合集 (全 十二 册). 4th edition Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 2003. ISBN 7-101-00475-X /K.210

- Collections of essays from Book 1 to Book 5: - Original editions 1–9

- Book 2: vol 10-19

- Book 3: vol 20-26

- Book 4: vol 27-37

- Book 5: vol 38-45

Monographic collections 6–12

- Book 6: vol 1–21

- Book 7: vol 22-29

- Book 8: vol 30-45

- Book 9: vol 46-72

- Book 10: vol 73-87

- Book 11: vol 88-95

- Book 12: vol 96-104

Complete editions / collected works

- Yinbingshi heji / zhuanji 飲 冰 室 合集 / 專集 (Collected Works from the Chamber of the Ice Drinker). 40 vols. Shanghai 上海: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局, 1932.

- Yinbingshi wenji 飲 冰 室 文集 (Collected Works from the Ice Drinker's Chamber). 2 vols. Taibei 臺北: Xinxing Shuju 新興 書局, 1955.

- Yinbingshi wenji leibian 飲 冰 室 文集 類 編 (Collected works from the ice drinker's chamber in chronological order). Taibei 臺北: Huazheng Shuju 華 正 書局, 1974.

- Liang Qichao xuanji 梁啟超 年 選集 (Selected Works by Liang Qichao). Edited by Li Huaxing 李華興 and Wu Jiaxun 吳嘉勛. Shanghai 上海: Renmin Chubanshe 人民出版社, 1984.

- Liang Qichao quanji 梁啟超 全集 (The Complete Writings of Liang Qichao). Edited by Zhang Dainian 張岱年, Dai Tu 戴 兔, Wang Daocheng 王道成, Zhu Shuxin 朱 述 新 and Tao Xincheng 陶信成. 10 vols. Beijing 北京: Beijing Chubanshe 北京 出版社, 1983.

- Yichou chongbian Yinbingshi wenji 乙丑 重 編 飲 冰 室 文集 (Collected works from the ice drinker's chamber, revised in Yichou [1925]). Ed. And edited (點 校) by Wu Song 吳松 (among others). 6 vols. Kunming 昆明: Yunnan Jiaoyu Chubanshe 雲南 教育 出版社, 2001.

Nianpu (Chronicles)

- Liang Qichao nianpu changbian 梁啟超 年譜 長 編 (Chronicle of Liang Qichao). Edited by Ding Wenjiang 丁文江 and Zhao Fengtian 趙豐田. Shanghai 上海: Renmin Chubanshe 人民出版社, 1983.

Individual works in new publication

- Zhongguo jin sanbai nian xueshushi 中國 近三 百年 學術 史 (China's history of science over the past 300 years). Tianjin 天津: Tianjin Guji Chubanshe 天津 古籍 出版社, 2003.

- Qingdai xueshu gailun / Rujia zhexue 清代 學術 概論 / 儒家 哲學 (Overview of Science in the Qing Period / Confucian Philosophy). Tianjin 天津: Tianjin Guji Chubanshe 天津 古籍 出版社, 2003.

literature

- Chang, Hao: Liang Ch'i-Ch'ao and Intellectual Transition in China. Oxford University Press , London 1971

- Chen, Chun-chi: Politics and the Novel: A Study of Liang Ch'i-Ch'ao's Future of New China and His Views on Fiction. University of Michigan , UMI dissertation services, Ann Arbor 1998

- d'Elia, Pascal M., SJ : Un maître de la Jeune Chine: Liang K'i-tch'ao. In: T'oung Pao. Vol. XVIII, pp. 247-294

- Huang, Philip C .: Liang Ch'i-ch'ao and Modern Chinese Liberalism. Publications on Asia of the Institute of Comparative and Foreign Area Studies, No. 22. University of Washington Press, Seattle 1972

- Jiang, Guangxue: Liang Qichao he Zhongguo gudai xueshu de zhongjie. (Liang Qichao and the end of ancient Chinese scholarship). Jiangsu Jiaoyu Chubanshe, Nanjing 2001

- Kovach, Bill and Tom Rosenstiel: The Elements of Journalism. Random House, New York 2001

- Levenson, Joseph: Liang Ch'i-Ch'ao and the Mind of Modern China. University of California Press , Los Angeles 1970

- Li, Xisuo 李喜 所; Yuan, Qing 元青: Liang Qichao zhuan 梁啟超 傳. Beijing 北京: Renmin Chubanshe 人民出版社, 1995.

- Li, Xisuo 李喜 所 et al. (Ed.) Liang Qichao yu jindai Zhongguo shehui wenhua 梁啟超 與 近代 中國 社會 文化. Tianjin 天津: Tianjin Guji Chubanshe 天津 古籍 出版社, 2005.

- Machetzki, Rüdiger: Liang Ch'i-ch'ao and the influences of German state theories on monarchical reform nationalism in China. Diss. Phil. University of Hamburg 1973

- Meng, Xiangcai 孟祥 才: Liang Qichao zhuan.梁啟超 傳. Beijing Chubanshe 北京 出版社, Beijing 北京 1980

- Metzger, Gilbert: Liang Qichao, China and the West after World War I. Lit, Münster 2006 ISBN 3-8258-9425-8

-

Mishra, Pankay ; Michael Bischoff (transl.): From the ruins of the empire. The revolt against the west and the resurgence of Asia. S. Fischer, Frankfurt 2013 ISBN 3100488385 ; therein chap. 3 and ex. Bibliography for chap. 3 (from English)

- From the ruins of the empire. The revolt against the west and the resurgence of Asia. License issue. Series of publications, 1456. Federal Agency for Civic Education BpB, Bonn 2014 ISBN 3838904567 : Liang Qichaos China and the fate of Asia, pp. 155–226; Epilogue Detlev Claussen : New Age, New World Views , pp. 379–394

- Shin, Tim Sung Wook: The Concepts of State (kuo-chia) and People (min) in the late Ch'ing, 1890-1907: The Case of Liang Ch'i Ch'ao, T'an S'su-t 'ung and Huang Tsun-Hsien. University of Michigan UMI, Microfilms International, Ann Arbor 1986

- Tang, Xiaobing: Global space and the Nationalist Discourse of Modernity. The Historical Thinking of Liang Qichao. Stanford University Press , 1996

- Wang, Xunmin: Liang Qichao zhuan. Tuanjie Chubanshe, Beijing 1998

- Wu, Qichang: Liang Qichao zhuan. Tuanjie Chubanshe, Beijing 2004

- Xiao, Xiaosui. China Encounters Western Ideas 1895-1905: A Rhetorical Analysis of Yan Fu, Tan Sitong and Liang Qichao. University of Michigan UMI, Dissertation Services, Ann Arbor 1992

- Zhang, Pengyuan 張 朋 遠: Liang Qichao yu Qingji geming.梁啟超 與 清 季 革命 (Liang Ch'i-ch'ao and the Late Ch'ing Revolution). Institute of Modern History Academia Sinica Monograph Series, No. 11. 3rd edition. Institute of Modern History, Taibei 臺北 1982

- Zheng, Kuangmin 鄭 匡 民: Liang Qichao qimeng sixiang de dongxue beijing.梁啟超 啟蒙 思想 的 東 學 背景. Shanghai Shudian, Shanghai 2003

Web links

- Literature by and about Liang Qichao in the catalog of the German National Library

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Liang, Qichao |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Chinese scholar, journalist, philosopher and reformer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 23, 1873 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Xinhui , Guangdong |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 19, 1929 |

| Place of death | Beijing |