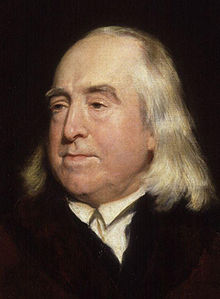

Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (born February 15, 1748 in Spitalfields , London , † June 6, 1832 ibid) was an English lawyer , philosopher and social reformer .

Bentham is considered to be the founder of classical utilitarianism . He was one of the most important social reformers in England in the 19th century and a pioneer of the modern welfare state. He called for general elections, women's suffrage , the abolition of the death penalty , animal rights , the legalization of all sexual preferences ( homosexuality , pederasty , sodomy ) and freedom of the press . He is considered a pioneer of feminism , a pioneer of democracy , liberalism and the rule of law . But Bentham is also known for his sharp criticism of the French declaration of human rights and his advocacy of usury . He also provided arguments for the legitimate use of torture and developed the Panoptikum, a model prison that Michel Foucault chose as a symbol for the structures of surveillance and rule in modern civil society.

biography

Jeremy Bentham was born near London in 1748 to a wealthy lawyer . In his youth he was considered a child prodigy. He began studying law and philosophy at Oxford when he was only twelve . However, studying opaque common law did not suit his spiritual temperament. He was much more impressed by the exact sciences. Isaac Newton , Joseph Priestley and Carl von Linné became his intellectual role models. In addition to the natural sciences, contemporary Enlightenment philosophers such as Voltaire , David Hume , Cesare Beccaria and, in particular, Claude Adrien Helvétius Bentham shaped thought.

Bentham trained as a lawyer, but broke off his practical legal career very quickly and devoted himself to science and political reform. In the beginning he was hardly noticed by the public, especially in his home country. Bentham received his first honorary title from post-revolutionary France, where he was granted honorary French citizenship in 1792 together with George Washington , Friedrich Schiller and Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi . In England itself, Bentham's level of fame did not grow until the early 19th century.

Bentham was the head of the English radicals , the political arm of philosophical utilitarianism , which had a lasting influence on English domestic politics and which later became part of the Liberal Party . Through his followers - including James Mill and his son John Stuart Mill , David Ricardo and John Austin - his teachings had great political influence.

Bentham created opponents mainly in Germany. In the first half of the 19th century, Bentham's radical atheism , materialism and democracy stood at right angles to the romantic-idealistic zeitgeist. But even in idealistic and historical philosophy, Bentham's utilitarian ethic was very difficult to establish. Profane pursuit of happiness and usefulness calculations contradicted the zeitgeist of classicism and Biedermeier .

The 80-year-old Goethe, for example, described Bentham, who was roughly the same age, to Johann Peter Eckermann on March 17, 1830 as a “highly radical fool” and remarked: “To be so radical at his age is the height of all madness.” Karl Marx thought for them Teach Bentham only drastic words: In Das Kapital. Volume I writes Marx: "If I had the courage of my friend H. Heine , I would call Mr. Jeremias a genius in bourgeois stupidity."

Car icon

After his death, Bentham was dissected in the presence of anatomy students and his closest confidants (including his friend and doctor, Dr. Southwood Smith). According to his last will, his body was "auto-iconized". Auto-iconization means that the corpse - either whole or only the head - is mummified using the methods of New Zealand Maori in order to preserve it for posterity. Bentham defines the term car icon as “a man who is his own image”. Through the car iconization, every person should create his own, lifelike monument as a car icon after his death. Bentham's skeleton was dressed in his clothes, which were stuffed with straw. However, his head was so disfigured by the car icon that a wax model was made for the car icon. Bentham's iconic car was displayed sitting on a chair in a showcase at University College London, wax head and walking stick in hand . The mummified head was initially placed in the showcase at the feet of the iconic car; today it is kept in the college archives.

ethics

The greatest happiness of the greatest number (greatest happiness principle) is the guiding principle of Bentham's utilitarian ethics . An action is judged solely on the basis of its social consequences: it is morally correct if it benefits the general public (or the greatest number); it turns out to be morally wrong if it harms the general public. In this sense the utilitarian ethic is consequentialist ; d. H. Inner motives do not play an independent role in evaluating an action.

The principle of the greatest happiness of the greatest number includes the demand for equality, understood as equal consideration of happiness in the evaluation of the consequences of actions.

Animal and human rights

Jeremy Bentham is one of the first advocates of animal rights , which he deduces from animals' pain perception , which is equal to humans . The ability to suffer was decisive for him, not the possession of reason or the ability to think. Otherwise, you would be likely to abuse many people, for example infants and people with severe intellectual disabilities .

“It may one day come to be recognized that the number of the legs, the villosity of the skin, or the termination of the os sacrum are reasons equally insufficient for abandoning a sensitive being to the same fate. What else is it that should trace the insuperable line? Is it the faculty of reason or perhaps the faculty of discourse? But a full-grown horse or dog is beyond comparison a more rational, as well as more conversable animal, than an infant of a day or a week or even a month old. But suppose they were otherwise, what would it avail? The question is not, Can they reason ?, nor Can they talk? but, Can they suffer? ”

“The day may come when one realizes that the number of legs, the hairiness of the skin or the end of the sacrum are equally insufficient arguments for leaving a sentient being to the same fate. Otherwise, why should the insurmountable limit lie here? Is it the ability to think or maybe the ability to speak? But a fully grown horse or dog are incomparably more sensible and communicative animals than a day, week, or even a month old baby. But assuming this wasn't the case, what would that matter? The question is not, 'Can you think?' or 'Can they talk?' but ' Can they suffer? . "

“Why should the law refuse its protection to any sensitive being? The time will come when humanity will extend its mantle over everything which breathes. "

“Why should the law deny its protection to any sentient being? The time will come when mankind will take everything that breathes under its umbrella and shield. "

Legal theory

Bentham was the first exponent of systematic legal positivism , which exerted a great influence on the modern understanding of law primarily through his student John Austin , but later also through Hans Kelsen and HLA Hart . Bentham developed a clear conceptual separation of morality and law and vehemently rejected both the notion of natural law and the notion of natural rights. His assessment of the French declaration of human rights as "nonsense on stilts" ( nonsense upon stilts ) is famous .

Bentham's legal theory was based on an extremely individualistic view of man. For Bentham, humans were utility maximizers who pursued their own interests without any consideration for their fellow human beings. The law therefore has the social function of forcing citizens to be commoners. The key to the greatest happiness of the greatest number is formed by systematic criminal legislation designed according to rational criteria, which is intended to make citizens aware of their legal obligations and the impending sanctions. The term codification is - like the term international - a word creation by Bentham.

Bentham's theory of criminal law, which is closely based on Beccaria , is shaped by the idea of prevention. Like Paul Johann Anselm von Feuerbach later , Bentham believed that legal penalties could largely deter citizens from breaking the law (so-called theory of psychological coercion). Both the criminal law and the punishment itself are intended to be a deterrent and bring about the highest degree of social conformity. Bentham spoke out against the criminal law of guilt and advocated relative punitive purposes: the punishment should not aim to compensate for injustice committed, but only to prevent future injustice. Reform of the penal system was also a major concern of Bentham. In this context he drafted the plan for a totally monitored penal institution, the Panopticon, using the facilities of his brother Samuel Bentham that had been tried and tested in Russia .

Constitutional theory

In his Constitutional Code of 1831, Bentham developed a model of democracy based on popular sovereignty, general elections, extensive government transparency and freedom of expression and freedom of the press, which, together with the works of James Madison and James Mill, forms one of the classic foundations of today's liberal democratic constitutional theory. The starting point for his constitutional theory is the idea that any form of political power harbors the risk of abuse of power and political corruption. The purpose of the constitution is therefore to consistently bind the political rulers (ministers, parliamentarians, judges and administrative officials) to the interests of the population through constitutional control mechanisms. In contrast to the classic three-way division based on Montesquieu , Bentham distinguished four state powers: In addition to the legislature, the executive and the judiciary, he led the people as constitutive as the supreme power. The English reform of the electoral law of 1832 - the so-called Reform Act - was largely initiated by Bentham and his colleagues.

Bentham's concept of freedom

Bentham is counted together with Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill "to the first guard of the British economists and state theorists of the liberal era". Bentham's liberal stance, however, was limited to economic policy. In all other areas of society, the state has been assigned a central role. Because Bentham believes that every citizen takes advantage of every freedom that is allowed to him to gain advantages at the expense of others, individual freedom must be so narrowly defined by the state that it can no longer cause harm. More than the individual freedom of citizens, Bentham was interested in their security. Bentham even went so far as to equate security with freedom. For Bentham, man is free when he is protected from encroachments by his fellow citizens and excessive power of his government and can be sure of the inviolability of his life, his health, his honor, his contracts and his property.

The far-reaching rights that citizens enjoy in Bentham's political doctrine are only made possible by a powerful state monitoring and control apparatus that educates, trains and conditions people from an early age, permanently monitors their behavior and punishes and corrects any wrongdoing with sanctions . Through Bentham's concept of freedom as security, even the most serious interventions by the state in the personal freedom of citizens do not have a negative effect on their freedom. Rather, they form the prerequisite for civil liberty. In this context, Bentham not only called for the judicial system and the police to be strengthened, but also for the identification service to be tattooed for the population and the systematic use of informers and undercover agents .

Quotes

- "Under a government of laws, what is the motto of a good citizen? To obey punctually; to censure freely. ”(A Fragment on Government, p. 10).

- "It is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong" (A Fragment on Government, preface, p. 393).

- "Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to determine what we shall do. On the one hand the standard of right and wrong, on the other the chain of causes and effects, are fastened to their throne "(Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, ch. I, 1, p. 11).

- "In the breast of every sensitive being, the general predominance of self-preference is prevalent universally: for proof take the existence of the species: look, and you will see, that upon such predominance the species is absolutely dependent for its existence" ( Economy as Applied to Office, ch. III § 1, p. 27).

- "Natural rights is simple nonsense, natural and imprescriptible rights, rhetorical nonsense, nonsense upon stilts" (Nonsense upon Stilts, Art. 2, p. 330).

- "I do really take it for an indisputable truth, and a truth that is one of the corner stones of political science ― the more strictly we are watched, the better we behave" (Farming Defended, p. 277).

- "Morality (...) is but a means to an end. The end of morality is happiness: morality is valuable no otherwise than as a means to that end: if happiness were better promoted by what is called immorality, immorality would become a duty, virtue and vice would change places ”(Nonsense Upon Stilts, Appendix C, p. 429).

- "What means liberty? What can be concluded from a proposition, one of the terms of which is so vague? What my own meaning is, I know; and I hope the reader knows it too. Security is the political blessing I have in view: security as against malefactors on one hand - security as against the instruments of the government, on the other "(Rationale of Judicial Evidence, Book IX Part VI, ch. I, p. 522) .

Most important works

- A Fragment on Government (1775, published 1776), in: A Comment on the Commentaries and A Fragment on Government, ed. by JH Burns / HLA Hart (The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham), London 1977, pp. 391-551.

- Constitutional Code; For the Use of All Nations and All Governments Professing Liberal Opinions Vol. I (1822–30, published 1830), ed. by Frederick Rosen / JH Burns (The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham), Oxford 1983.

- Defense of Usury; Shewing the Impolicy of the Present Legal Restraints on the terms of Pecuniary Bargains, (1786–87, published 1787), in: Werner Stark (Ed.), Jeremy Bentham's Economic Writings, Critical Edition, based on his printed works and unprinted manuscripts, Vol. I, London 1952, pp. 121-207.

- Translation: Defense of Usury , from English, with a preliminary remark and remarks by Richard Seidenkranz, Verlag Senging, Saldenburg, 2013, ISBN 978-3-9810161-8-5 .

- Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1780, published 1789), ed. by JH Burns / HLA Hart (The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham), London 1970, 2nd edition Oxford 1996,

- German excerpts in: Otfried Höffe, Introduction to utilitarian ethics, Beck, Munich 1975. ISBN 3-406-06077-3 .

- Translation: An introduction to the principles of morality and legislation , from the English by Irmgard Nash (Chapters I - XVII) and Richard Seidenkranz (remaining parts), Verlag Senging, Saldenburg, 2013, ISBN 978-3-9815841-0- 3 .

- Of Laws in General (1782), ed. by HLA Hart (The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham), London 1970.

- Panopticon, or, The Inspection-House (1787), in: The Panopticon Writings, ed. by Miran Božovič, London / New York 1995, pp. 31–95.

- Translation: The Panopticon . From the English by Andreas Leopold Hofbauer , ed. by Christian Welzbacher . Matthes & Seitz Berlin , Berlin 2013. ISBN 978-3-88221-613-4 .

- The Philosophy of Economic Science, in: Werner Stark (Ed.), Jeremy Bentham's Economic Writings, Vol. I, London 1952, pp. 79-120.

- Principles of the Civil Code (1786), in: The Works of Jeremy Bentham, ed. by John Bowring, Volume I, Edinburgh 1838-43, pp. 297-364, reprinted New York 1962.

- Translation: principles of legislation. Arend, Cologne 1833 ( digitized edition of the University and State Library Düsseldorf ).

literature

- James E. Crimmins: Secular Utilitarianism. Social Science and the Critique of Religion in the Thought of Jeremy Bentham. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1990, ISBN 0-19-827741-5 .

- Stephen G. Engelmann: Imagining Interest in Political Thought. Origins of Economic Rationality. Duke University Press, Durham MD et al. 2003, ISBN 0-8223-3135-7 .

- Michel Foucault : Surveiller et punir. Naissance de la prison. Gallimard, Paris 1975.

- Elie Halévy: La formation du radicalisme philosophique. 3 volumes. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 1995,

- Volume 1: La jeunesse de Bentham 1776–1789. ISBN 2-13-046998-1 ;

- Volume 2: L'évolution de la doctrine utilitaire de 1789 à 1815. ISBN 2-13-046999-X ;

- Volume 3: Le radicalisme philosophique. ISBN 2-13-047000-9 .

- Ross Harrison: Bentham. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London et al. 1983, ISBN 0-7100-9526-0 .

- HLA Hart: Bentham. Lecture on a Master Mind. In: Proceedings of the British Academy. 48, 1962, ISSN 0068-1202 , pp. 297-320.

- Otfried Höffe : On the theory of happiness in classical utilitarianism. In: Otfried Höffe: Ethics and Politics. Basic models and problems of practical philosophy (= Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch Wissenschaft 266). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1979, ISBN 3-518-07866-6 , pp. 120-159.

- Wilhelm Hofmann: Politics of the enlightened happiness. Jeremy Bentham's philosophical-political thinking (= Political Ideas 14). Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-05-003710-5 .

- Paul Kelly: Utilitarianism and Distributive Justice. Jeremy Bentham and the Civil Law. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1990, ISBN 0-19-825418-0 ( Also : London, Univ., Diss.).

- Georg Kramer-McInnis: The “legislator of the world”. Jeremy Bentham's foundation of classical utilitarianism with special consideration of his legal and political theory (= European legal and regional history 7). Dike et al., Zürich et al. 2008, ISBN 978-3-03-751119-0 (also: Zürich, Univ. Diss., 2007).

- Douglas G. Long: Bentham on Liberty. Jeremy Bentham's idea of liberty in relation to his utilitarianism. University of Toronto Press, Toronto et al. 1977, ISBN 0-8020-5361-0 .

- Steffen Luik: The reception of Jeremy Bentham in German law (= research on German legal history 20). Böhlau, Cologne et al. 2003, ISBN 3-412-09202-9 (also: Tübingen, Univ., Diss., 2001).

- Gregor Ritschel: Jeremy Bentham and Karl Marx. Two perspectives on democracy. transcript Verlag, Bielefeld 2018, ISBN 978-3-8376-4504-0 .

- Frederick Rosen: Jeremy Bentham and Representative Democracy. A Study of the Constitutional Code. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1983, ISBN 0-19-822656-X .

- Philip Schofield: Utility and Democracy. The Political Thought of Jeremy Bentham. Oxford University Press, Oxford et al. 2006, ISBN 0-19-820856-1 .

- Christian Welzbacher: The radical fool of capital. Jeremy Bentham, the »Panoptikum« and the »Auto Icon« . Matthes & Seitz, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-88221-570-0 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Jeremy Bentham in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Jeremy Bentham in the German Digital Library

- The Bentham Project , University College London

- Center Bentham , French online platform that publishes the Revue d'études benthamiennes .

- Revue d'études benthamiennes , biannual scientific online journal since 2006, published by the French Center Bentham (peer-reviewed).

- William Sweet: Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832). In: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Jeremy Bentham , English-language biographical profile on Utilitarianism.net .

proof

- ↑ James Steintrager: Bentham ( Political Thinkers Volume V ). London 2004, p. 12 f.

- ↑ See William Thomas, The Philosophical Radicals. Nine Studies in Theory and Practice 1817-1841, Oxford 1979, p. 446 ff.

- ↑ cit. according to Eckermann, Conversations with Goethe in the last years of his life, ed. by Christoph Michel: Johann Wolfgang Goethe. Complete Works. Letters, Diaries and Conversations , Vol. 12, Frankfurt a. M. 1999, p. 715; http://www.zeno.org/nid/20004867432

- ↑ Marx, Das Kapital. Critique of Political Economy (1867), in: Karl Marx / Friedrich Engels Gesamtausgabe, Volume II / 5, Berlin 1983, p. 492 .; Volume I: The Production Process of Capital , footnote 870 http://www.zeno.org/nid/20009218653

- ^ Bentham, Auto Icon; or, Farther uses of the Dead to the Living , ed. by James E. Crimmins in: Ders., Bentham's Auto-Icon and Related Writings, Bristol 2002, p. 2.

- ^ UCL Bentham Project: Auto-Icon ; Bentham's Preserved Head ( Memento of the original from March 11, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Nonsense upon Stilts, or Pandora's Box Opened (1795), in: Rights, Representation and Reform. Nonsense Upon Stilts and Other Writings on the French Revolution, ed. by Philip Schofield, Catherine Pease-Watkin and Cyprian Blamires (The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham), Oxford 2002, pp. 317-434, Art. 2, p. 330.

- ↑ See Held, Models of Democracy, 3rd A. , Cambridge / Malden 2006, pp. 75 ff.

- ^ Bentham, Constitutional Code: For the Use of All Nations and All Governments Professing Liberal Opinions Vol. I , ed. by Frederick Rosen / JH Burns (The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham), Oxford 1983, ch. IV Art. 1, p. 26.

- ↑ Volker Müller, State Activity in the State Theories of the 19th Century , Diss. Konstanz 1990, Opladen 1991, p. 21

- ^ "The liberty which the law ought to allow of, and leave in existence, leave uncoerced, unremoved, is the liberty which concerns those acts only, by which, if exercised, no damage would be done to the community upon the whole: that is, either no damage at all, or none but what promises to be compensated by at least equal benefit "(Bentham, Nonsense Upon Stilts , Art. 4, p. 340).

- ^ "That which under the name of Liberty is so much magnified, as the invaluable, the unrivaled work of Law, is not liberty, but security"; quoted in Long, Bentham on Liberty. Jeremy Bentham's idea of liberty in relation to his utilitarianism , Toronto / Buffalo 1977, p. 74.

- ↑ See Bentham, Indirect Means of Preventing Crimes, in: The Works of Jeremy Bentham , ed. by John Bowring Volume I, Edinburgh 1838-43, pp. 533-580, reprint New York 1962, ch. XII, p. 557.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Bentham, Jeremy |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English philosopher and social reformer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 15, 1748 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Spitalfields , London |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 6, 1832 |

| Place of death | London |