Johann Peter Eckermann

Johann Peter Eckermann (born September 21, 1792 in Winsen (Luhe) , † December 3, 1854 in Weimar ) was a German poet , writer and close confidante of Goethe .

Life

Eckermann was born on September 21, 1792 in poor circumstances in Winsen (Luhe) , a small town near the Elbe at the gates of Hamburg . As a child he moved with his father, a peddler , through the Winsener Marsch and the northern Lüneburg Heath to sell all kinds of goods in the villages. He only attended school irregularly, but soon attracted attention due to his intellectual abilities and artistic talents. A Winsen bailiff and the local clergyman supported him, so that between 1808 and 1813 he found jobs as clerk in his hometown, in Uelzen and Bevensen .

After his time as a soldier (1813/14), following his wish to become a painter , he emigrated to Hanover to be trained by the painter Ramberg . Illness and lack of money forced him after a short time to give up this project and again to take a position in the state administration (War Chancellery Hannover). He saw that he had to continue his intellectual education, attended grammar school in Hanover on the side and devoted himself to a wide range of literature. He was particularly impressed by the works of Goethe.

After the short period of high school , which he dropped out without leaving school, Eckermann attended legal and philological courses at the University of Göttingen , but he soon had to stop this course due to lack of money. In 1822 he settled in Empelde near Hanover. There the parents of Heimburg's college friend from Göttingen granted him free lodging. The great role models now spurred him on to write verses himself. In addition, the articles on poetry were made with special reference to Goethe , the manuscript of which he sent to Goethe in Weimar .

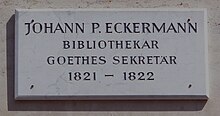

The positive response from Weimar prompted him to personally visit Goethe, who was almost seventy-four years old, on June 10, 1823. The ambitious young guest immediately accepted the suggestion of his “unmistakable guiding star” to take over some editorial and organizational work. However, he did not become Goethe's secretary, as could be read for decades on the memorial plaque on the Weimar Eckermann House in Brauhausgasse. Rather, he was in a non-binding courtesy relationship with him.

As in previous years, Eckermann's Weimar period was dominated by financial difficulties. Goethe made sure that the contributions to the poetry at Cotta were published for a fee. He also provided him with paid jobs, for example as a teacher to the Hereditary Prince Carl Alexander . He also received his doctorate from the University of Jena in 1825 on his initiative. However, Eckermann was only just able to make a living, especially since the work for Goethe was often extremely demanding on him. Goethe's confidence in Eckermann's reliability was so great that he asked him to accompany his unstable son August 1830 on his fateful trip to Italy.

It was not until 1831 that Eckermann was able to marry his long-term fiancée Johanne Bertram in Northeim . She died in April 1834 shortly after the birth of her son Johann Friedrich Wolfgang, called Karl , who later became a respected painter.

The aged Goethe put Eckermann in his will as the main editor of his literary estate in return for a profit sharing . This resulted in fifteen volumes which Eckermann published after Goethe's death (1832). Nevertheless, hardly anyone in Weimar took any notice of the ailing, gradually impoverished Eckermann. In 1836 his long-prepared conversations with Goethe in the last years of his life finally appeared in two volumes, a work that is still recognized today and has been translated into numerous languages.

Two years later Eckermann published another volume of poetry, in 1848 a third volume of his conversations with Goethe , but the fee income was so low that he could not live on it for long. Two severe strokes prevented the completion of a planned fourth volume of the talks with a focus on Goethe's Faust .

On December 3, 1854, Eckermann died ill and alone in the presence of his son Karl in Weimar. The Grand Duke Carl Alexander, whom Eckermann had taught as a pupil, made sure that there was a dignified grave in the immediate vicinity of Goethe's final resting place in the Weimar Historical Cemetery .

In 1929, the then middle school, now the secondary school, in Winsen (Luhe) was named Johann-Peter-Eckermann-Schule . In 1932 the former Schulstrasse in Winsen (Luhe) was named after Eckermann.

meaning

It was less his poems, which appeared in a second volume in 1838, than the transcription of his conversations with Goethe in the last years of his life that made Eckermann widely known and earned him great recognition. The judgments about the young friend and assistant of the great poet have always diverged. Friedrich Hebbel explained: "Eckermann in no way appears to me to be any significant person". Goethe himself stated: "Eckermann [...] is [...] especially the reason that I am continuing Faust". "Because of the supportive participation" he considered it to be "very inestimable."

Eckermann's importance is generally recognized by Goethe research today. Regarding the question of the authenticity of the conversations communicated, one must note his express remark in the foreword , according to which it is about “my Goethe”, who has his say in the book. For the interviews published in 1836, Eckermann was able to fall back on extensive material; at the same time, however, one will already have to take a strong creative element into account. The conversations of the third part, published in 1848, are based largely on very fragmentary notes and on third-party notes, especially those of Frédéric Soret . In no case can Eckermann's communications be understood as Goethe's own words (or even as part of his work).

Resentment and a lack of knowledge about Eckermann's role in Goethe's life, which is widespread to this day, often led to a judgment marked by arrogance and ridicule. Eckermann's own poetic efforts probably also contributed to this. Among the former contemporaries especially did Heinrich Heine out that mocked him several times. More recently, Martin Walser exposed Eckermann to ridicule in his play “In Goethe's Hand”. Friedrich Nietzsche (e.g. 1878) and Christian Morgenstern (1909), on the other hand, judged Eckermann's “Conversations with Goethe” with appreciation. Nietzsche even called it “the best German book there is”.

As “Goethe's secretary”, Eckermann felt misunderstood during his lifetime: “That alone is not a true word!” He protested, listed the secretaries that Goethe employed and personally rejected such a classification. He saw himself as a companion and friend of the poet prince, in whose service he put nine years of his life and creativity. Goethe called him his "tested house and soul friend" and "loyal Eckart".

It is questionable whether Goethe would have decided to write down Faust II without Eckermann's insistence , and the clear presentation of his entire lyric works is undoubtedly his merit. Eckermann's direct sketches in his main work, Conversations with Goethe in the last years of his life , published in 1836, have retained their originality and validity even for today's readers. Many passages in the text can stand alone as guiding principles and wisdom, even without the further context of the text, and quite a few may be read as appropriate comments or critical remarks on contemporary phenomena.

Works

- Poems. Self-published, Hanover 1821.

- Contributions to poetry with special reference to Goethe. Cotta, Stuttgart 1824.

- Weimar's jubilee festival on September 3rd, 1825. First section: The celebration of the residential city of Weimar, with the inscriptions, speeches given and published poems. With eight copper plates. Weimar. 1825. Second Division: including the celebration in the other towns and cities of the Grand Duchy. Weimar, 1826. With a foreword by Friedrich v. Müller (ed.), Weimar, by Wilhelm Hoffmann.

- Poems. Brockhaus, Leipzig 1838; Reprint Weimar 2009, ISBN 978-3-941190-82-5 .

-

Conversations with Goethe in the last years of his life. Brockhaus, Leipzig 1836, and Heinrichshofen, Magdeburg 1848:

- First part. Brockhaus, Leipzig 1836. ( digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- Second part. Brockhaus, Leipzig 1836. ( digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- Third part. Heinrichshofen, Magdeburg 1848. ( digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- Deutscher Klassiker Verlag, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-618-68050-5 (fully commented edition)

- Very numerous reprints and reprints, e.g. E.g .: btb, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-442-72956-4 .

- Letters to Auguste Kladzig , Insel-Verlag 1924.

literature

- Hans Heinrich Borcherdt: Eckermann, Johann Peter. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 4, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1959, ISBN 3-428-00185-0 , p. 289 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Jutta Hecker : In the shadow of Goethe. A Eckermann novella. Weimardruck, Weimar 1999.

- Helmuth Hinkfoth: Eckermann. Goethe's interlocutor. A biography. 2014, ISBN 978-3-9809115-8-0 .

- Helmuth Hinkfoth: Eckermanns marriage with Johanne Bertram in Northeim in the year 1831. In: Northeimer Jahrbuch. Vol. 78 (2013) pp. 75–81.

- Helmuth Hinkfoth (ed.): In the evening an hour with Goethe. Stories, poems, letters and reflections by Johann Peter Eckermann. HuM-Verlag, Winsen (Luhe), 2nd edition 2018, ISBN 978-3-946053-12-5 .

- Helmuth Hinkfoth (ed.): The correspondence between Goethe and Eckermann. Heimat- und Museumverein, Winsen (Luhe), 2nd edition. 2018, ISBN 978-3-946053-13-2 .

- Helmuth Hinkfoth: "If only it weren't for coming back " - JP Eckermann's leisurely travels; with documentation of all verifiable whereabouts and apartments of JP Eckermann. HuM-Verlag, Winsen (Luhe) 2015, ISBN 978-3-946053-01-9 .

- Heinrich Hubert Houben : Johann Peter Eckermann. His life for Goethe. Depicted from his newly found diaries and letters. 2 volumes. Haessel , Leipzig 1925–1928.

- Stephan Porombka: The Eckermann workshop. The conversations with Goethe as an exercise in contemporary literature. In: Stephan Porombka, Wolfgang Schneider, Volker Wortmann (ed.): Yearbook for cultural studies and aesthetic practice. Tübingen 2006, pp. 138–159. Online (PDF)

- Heiko Postma : "I think and speak of nothing but Goethe" - About the writer and Adlatus Johann Peter Eckermann (1792-1854) . jmb, Hannover 2011, ISBN 978-3-940970-17-6 .

- Uwe Repinski: The very simple Mr. Eckermann, in: Peter Hertel u. a .: Ronnenberg. Seven Traditions - One City, Ronnenberg 2010, ISBN 978-3-00-030253-4 .

- Arnold Zweig : The assistant. In: Called Shadows. Tillgner, Berlin 1923 (series: Das Prisma, 9); under this title again Reclam, Lpz. 1926 epilogue Heinz Stroh (also: TB RUB 6711), again ibid. TB 1947 and others; again in dsb .: girls and women. 14 stories. Gustav Kiepenheuer, Berlin 1931, pp. 25–38; again in dsb .: The assistant u. a. Deuerlich, Göttingen 1989.

Audio books

- Johann Peter Eckermann: Conversations with Goethe in the last years of his life. 1st and 2nd part, read in full by Hans Jochim Schmidt. Schmidt Hörbuchverlag, ISBN 978-3-941324-96-1 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Johann Peter Eckermann in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Johann Peter Eckermann in the German Digital Library

- Works by Johann Peter Eckermann in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Annotated link collection of the university library of the FU Berlin ( Memento from October 11, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (Ulrich Goerdten)

- Johann Peter Eckermann in the Internet Archive

- Johann Peter Eckermann - A portrait in texts, pictures and documents

- Conversations with Goethe in the last years of his life Glanz & Elend

- Eckermann's grave - resting place of a meritorious man by Florian Russi

- Goethe's Faust at the Emperor's court : arranged in three acts for the stage by Johann Peter Eckermann. Edited from Eckermann's estate by Friedrich Tewes .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Uwe Repinski: The very simple Mr. Eckermann, in: Peter Hertel u. a .: Ronnenberg. Seven Traditions - One City, Ronnenberg 2010, ISBN 978-3-00-030253-4 , pp. 269-271.

- ↑ Uwe Repinski: The very simple Mr. Eckermann, in: Peter Hertel u. a .: Ronnenberg. Seven Traditions - One City, Ronnenberg 2010, ISBN 978-3-00-030253-4 , p. 269.

- ↑ The first English translation of the conversations appeared as early as the middle of 1839, and another followed in 1850. There are currently editions in French, Italian, Russian, Spanish, Swedish, Danish, Dutch, Czech, Hungarian, Japanese and Turkish, among others.

- ↑ See travel pictures. Third part. Journey from Munich to Genoa. In: Heinrich Heine. Works and letters in ten volumes. Published by Hans Kaufmann. Aufbau Verlag, Berlin and Weimar 1972, p. 249.

- ↑ Martin Walser: In Goethe's hand. Scenes from the 19th century . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1982.

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche: Menschliches, Allzumenschliches II, The Wanderer and his shadow . No. 109; KSA 2, p. 599.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Eckermann, Johann Peter |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German poet |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 21, 1792 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Winsen (Luhe) |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 3, 1854 |

| Place of death | Weimar |