Division of Korea

The division of Korea into a north and a south part, from which the states known as North and South Korea emerged , dates back to 1945 after the end of the Second World War with the establishment of the two zones of occupation .

Division after World War II

After the defeat and surrender of Japan in the Pacific War , the Allies occupied not only what is now Japan itself, but also Korea, which was annexed by Japan in 1910 and incorporated into it as the province of Chosen . In a controversial decision among the Korean population - which was finally hoping for state sovereignty - the UN Trustee Council initially transferred the fiduciary administration of the country to the Soviet Union and the USA .

The two victorious powers of World War II divided the country between themselves along the 38th parallel. The Soviet Union, whose Red Army had occupied the Japanese-controlled Manchuria shortly before the end of the war in the Manchurian Operation , took over the northern part, while the United States administered the south. The aim of the trusteeship should be to establish a provisional Korean government that should be "free and independent in its direction".

The planned - all-Korean - elections did not take place because the Soviet Union suspended the implementation of the plans of the United Nations due to the increasing tensions in the beginning Cold War between the allies of the Second World War . As a result, separate elections were held in both occupation zones, which were largely boycotted in the southern US-controlled area.

After the election in the southern zone of occupation, the two occupying powers established independent, autonomous Korean states on their territory and set up governments to take their course. South Korea was first founded as the Republic of Korea on August 15, 1948, and shortly afterwards North Korea as the Democratic People's Republic of Korea on August 26, 1948. Both states proclaimed sovereignty over the entire peninsula from the very beginning of their existence. The Soviet occupation forces withdrew in 1948 and the US in 1949.

Division after the Korean War

In June 1950 North Korea attempted to force the unification of the country by means of a military attack on the south. A number of Western states participated on the side of South Korea in the resulting Korean War , covered by a resolution of the United Nations Security Council directly with troops. On the North Korean side, troops from the young People's Republic of China later entered the war. Indirect aid in the form of war material and trainers came from the Soviet Union.

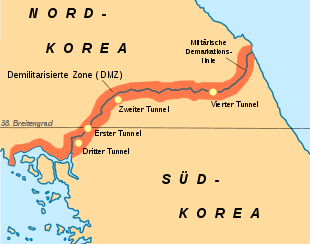

After the armistice in July 1953, which ended the fighting, the division of the peninsula continued. Since then, it has run along a demarcation line that is roughly at the 38th parallel (see map). A demilitarized zone was established around the demarcation line in accordance with the ceasefire regulations .

A communist regime established itself in the north , which abroad is commonly viewed as totalitarian and isolationist . The South - initially a dictatorship supported by the United States - has developed into a democracy based on the Western model. The economy of the initially much richer and more progressive North Korea began to suffer from the political conditions and collapsed in the 1990s, while South Korea has experienced an economic boom since the 1970s and is now one of the twenty largest economies in the world.

Since the end of the Korean War, there have been phases of rapprochement and alienation between the two states and a series of armed border incidents (see also the Korean conflict ). Both countries, which officially continue to strive for Korean reunification , have highly armed and numerically strong armed forces.

literature

- Seung-hun Chun: Strategy for Industrial Development and Growth of Major Industries in Korea. (PDF; 1.5 MB) Korea Institute for Development Strategy, 2010. Accessed September 9, 2012.

- Bruce Cumings: The Origins of the Korean War. Liberation and the Emergence of Separate Regimes, 1945–1947. Princeton University Press, Guildford, Princeton 1981, ISBN 978-0-691-09383-3 , OCLC 59867723 .

- Ann Sasa List-Jensen: Economic Development and Authoritarianism. A Case Study on the Korean Development State. (PDF; 164 kB) Aalborg University, Aalborg 2008, ISSN 1902-8679 . Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- Andrea Matles Savada and William Shaw: World War II and Korea. In: Andrea Matles Savada and William Shaw (Eds.): South Korea. A Country Study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC 1990, ISBN 978-0-16-040325-5 , OCLC 24667208 .

- Don Oberdorfer: The Two Koreas. A Contemporary History. Addison-Wesley, Reading, Massachusetts 1997, ISBN 978-0-201-40927-7 , OCLC 36776530 .

- Gregory Henderson, Richard Ned Lebow, John George Stoessinger: Divided Nations in a Divided World . D. McKay Co., New York 1974, ISBN 978-0-679-30057-1 .

- Quansheng Zhao, Robert G. Sutter: Politics of Divided Nations. China, Korea, Germany and Vietnam. Unification, Conflict Resolution and Political Development (= Occasional Papers / Reprints Series in Contemporary Asian Studies. Volume 9). School of Law, University of Maryland, Baltimore 1991, ISBN 978-0-925153-17-3 ( PDF file; 11.8 MB ).

- Thomas Cieslik: Reunions during and after the East-West bloc confrontation. Causes of the division - foundations of the (missing) unity. Investigated using the case studies of Vietnam, Yemen, Germany, China and Korea (= scientific articles from Tectum-Verlag. Sub-series Political Science. Volume 10). Tectum-Verlag, Marburg 2001, ISBN 978-3-8288-8271-3 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Andrea Matles Savada and William Shaw: World War II and Korea. 1990, pp. 24-25.

- ↑ At that time the USSR was boycotting the work of the UN, and her absence from the Security Council was considered an abstention. Otherwise this resolution would certainly have been prevented by a veto by the USSR.

- ^ Ann Sasa List-Jensen: Economic Development and Authoritarianism. A Case Study on the Korean Development State. 2008.

- ^ Seung-hun Chun: Strategy for Industrial Development and Growth of Major Industries in Korea. 2010.