Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty of 1905

| Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty of 1905 | |

|---|---|

| Japanese name | |

| Kanji | 第二 次 日韓 協約 |

| Rōmaji after Hepburn | Dai-ni-ji Nikkan kyōyaku |

| translation | Second Japan-Korean Agreement |

| Korean name | |

| Hangeul | 제 2 차 한일 협약 |

| Hanja | 第二 次 韓日 協約 |

| Revised Romanization | Je-i-cha Han-il hyeobyak |

| McCune-Reischauer | Che-i-ch'a Han-il hyŏbyak |

| translation | Second Korean-Japanese Agreement |

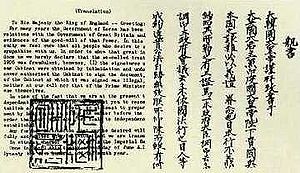

The Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty , also known as the Eulsa Treaty in Korean , was signed on November 17, 1905 between the government of the Korean Empire and the Japanese Empire under pressure from Japan. Emperor Gojong ( 고종 ), as sovereign of the state, refused to sign the treaty, which was favored by the aftermath of the Russo-Japanese War from which Japan emerged victorious.

The treaty resulted in Korea becoming a protectorate of Japan and thus losing its sovereignty .

Name of the contract

In Western publications the treaty is referred to as the "Protectorate Treaty". At the time of the conclusion of the contract, it was called Japanese-Korean negotiation agreement ( Japanese 日韓 交 渉 条約 , Nikkan kōshō jōyaku ), and in Korea Korean-Japanese negotiation agreement ( 한일 협상 조약 , 日韓 交 渉 條約 , Hanil hyeopsang joyak ).

In Japanese, the treaty is known under various names, including the "Second Japanese-Korean Agreement" ( 第二 次 日韓 協約 , Dainiji nikkan kyōyaku ). But it is also "Isshi Protection Treaty" ( 乙巳 保護 条約 , Isshi hogo jōyaku , also transcribed as Itsushi hogo jōyaku , which translates as "Itsushi Protection Treaty") and "Protection Treaty against Korea" ( 韓国 保護 条約 , Kankoku hogo jōyaku ) called.

The treaty is also known by various names in Korean, including the “Second Korean-Japanese Agreement” ( 제 2 차 한일 협약 , 第二 次 韓日 協約 , jeicha hanil hyeobyak ). But there it is mainly referred to as the Eulsa Treaty ( 을사 조약 , 乙巳 條約 , Eulsa joyak ). It is also called "Eulsa protection contract" 을사 보호 조약 , 乙巳 保護 條約 , Eulsa boho joyak .

The name "Isshi" (or "itsushi") and "Eulsa" (Jap. 乙巳 ;. Kor 을사 ) have their name from the Chinese calendar , which every one of its 60 cycles has its own name. The name corresponds to the 42nd year of the 60-year cycle of this calendar, for which the contract was signed.

history

Following the victory of Japan in the Russo-Japanese War with the resulting withdrawal of Russian hegemony over Korea , and the Taft-Katsura Agreement , in which the United States agreed not to interfere with Japan in matters affecting Korea the Japanese government to formalize its sphere of interest over the Korean Peninsula .

Envoys from the nations of Japan and Korea met in Hanseong (now Seoul ) in November 1905 to resolve their differences over issues relating to Korea's future foreign policy. America was not averse to letting Japan influence Korea at the time. In order to negotiate a protectorate treaty with the Korean government representatives, the Japanese politician Itō Hirobumi , who was already well known to the Korean side and was received with honors by Emperor Gojong in March 1904 , was selected. But Emperor Gojong was not convinced by Hirobumi and persistently refused the contract. Despite resistance, the Korean cabinet signed the Protectorate Treaty on November 17, 1905, allowing Japan to take full responsibility for Korea's foreign policy. At the same time, all trade affairs that passed through Korean ports were placed under Japanese supervision. This is to be managed through the creation of the new post of General President as a central contact point.

The treaty came into force after the signatures of five Korean ministers (who were later referred to by Korean historians as "the five Eulsa traitors"):

- Minister of Foreign Affairs Park Je-sun ( 박제순 , 朴 齊 純 )

- Minister of the Army Yi Geun-taek ( 이근택 , 李根澤 )

- Minister of the Interior Yi Ji-yong ( 이지용 , 李 址 鎔 )

- Minister of Agriculture, Trade and Industry Gwon Jung-hyeon ( 권중현 , 權 重 顯 )

- Minister of Education Lee Wan-yong ( 이완용 , 李 完 用 )

The contract was published on November 23rd. As a justification for accepting the terms of the treaty, Yi Wan-Yong also explained to the other four ministers: “The diplomacy of our country has been incessant to this day. As a result, Japan waged two major wars and suffered heavy losses, but ultimately guaranteed Korea's position. Should our diplomacy again lead to a disruption of Far Eastern relations, this would be unbearable, so that the demands cannot be rejected. Our nation has done this to itself [...]. Japan is determined to achieve its goals, and since Japan is strong and Korea is weak, we do not have the power to refuse. Today, since there are currently no conflicting feelings and no threat of crisis, we should achieve a harmonious understanding. "

Ultimately, this statement expressed the understanding that Korea was too weak to offer resistance to Japan and should therefore voluntarily make some concessions in the hope that Japan would continue to respect the "position of Korea". However, this hope was not fulfilled. With the Japan-Korea annexation treaty of 1910 , Korea lost the last remnants of its state independence and sank to the status of a Japanese colony .

The protectorate treaty of 1905 was expressly declared by both parties as "already null and void" in the basic treaty between Japan and the Republic of Korea in 1965.

Content of the contract

A total of five contractual items were recorded in this contract. The most important points and their most important content were:

- Article 1 stipulates that Japan will in future be responsible for foreign missions and representation for Korea.

- In Article 2, Japan undertook to continue and, if necessary, enforce all still valid agreements between Korea and foreign powers that it had already concluded. Korea, in turn, was not allowed to sign any further treaties with foreign powers.

- In Article 3, permanent representation of the Japanese government at the Korean imperial court was negotiated. This representation, called "General-Resident", had the task of taking care of diplomatic affairs and directing.

- In Article 5, Japan pledged to uphold the welfare and dignity of the Korean imperial family.

At Gojong's request, a time limit was incorporated into the contract. This was written down in the preamble. It reads that the treaty "should serve until the moment comes when it is recognized that Korea has achieved national strength."

Legality dispute, attempts to challenge and other aftermath

Legality dispute about the contract

Some statesmen have not signed the protectorate treaty. These were:

- Emperor Gojong of Great Korea

- Prime Minister Han Gyu-seol ( 한규설 , 韓 圭 卨 )

- Minister of Justice Yi Ha-yeong ( 이하영 , 李夏榮 )

- Minister of Finance Min Yeong-gi ( 민영기 , 閔 泳 綺 )

The missing signatures, especially those of the emperor, causing Korean historians to about the legal to dispute the contract legality. However, Itō Hirobumi was aware of Gojong's decree of August 3, 1885, according to which it was sufficient for contracts between Great Korea and other nations if the seal of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was present on the document. Pak Je-sun did this in his function as foreign minister by means of the appropriate seal; the contract came into force immediately.

As a reason for rejecting the terms of the treaty, Han Gyu-seol stated: Although he admitted that "[Korea] cannot maintain its independence on its own," he would refuse any imperial order from Gojong to sign the protectorate treaty even if this would result in forced resignation and punishment by the emperor for “disloyalty”.

People's protest

When the treaty became known to the people of Korea, there was also protest there. Jo Byeong-se and Mihn Yong-hwan , who were high officials and leading resistance against this protectorate treaty between Japan and Korea, committed suicide as a token of their resistance. Local yangbans and commoners formed volunteers , called righteous armies in Korea then (and now in North and South Korea ) . The groups founded on this occasion were (and are) called Eulsa Uibyeong ( 을사 의병 , 乙巳 義 兵 , Righteous Army against the Eulsa Treaty ).

Subsequent Avoidance

Gojong sent letters to the great powers asking for support against the entry into force and the "illegal signing" of the treaty. By February 21, 2008, 17 such letters could be identified as belonging to him on the basis of the imperial seal.

Later, in 1907, the Korean Emperor Gojong sent three secret envoys to the Hague Peace Conference to protest the entry into force of the treaty. However, the great powers of the world refused to allow Korea to participate in this conference. The treaty remained internationally undisputed until Japan's surrender in World War II .

Trivia

Immediately before the contract is signed

In order to be able to speak to all members of the Korean cabinet at the same time, November 17, 1905 was chosen as the date; that day the Cabinet was invited to lunch at the Japanese legation in the palace. This date became the date on which the contract was signed.

Itō had sentry posts for the Imperial Japanese Army along the path to the palace used by the ministers to be able to take part in lunch . these had been legally stationed in Korea since 1885 under the Treaty of Tientsin . Guard posts were also set up around the palace and at key positions in Hanseong. Officially, this was declared with the protection of all parties involved in the negotiations. It can be assumed, however, that Itō established a kind of "blackout" because he feared that protests by the people could disrupt the negotiations if information about this could be disclosed by the contracting parties in advance at this point in time. The ministers were also only informed of the content of the contract in the palace.

To the subsequent invalidation attempts

The allegation that is often made in the Korean media that Pak Je-sun did not seal himself, but was forced by the Japanese delegation or that the seal ring was stolen from him and the Japanese delegation sealed itself, is based on a speculation by Gojong. Shortly after signing the letter, he wrote down those assumptions, as at that time he did not want to believe that Pak Je-sun would do this without his express consent. To date, there is no evidence to support these claims. This assumption is no longer mentioned in Gojong's later letters (around 1906).

See also

literature

- WG Beasley : Japanese Imperialism 1894-1945 . Oxford University Press , 1991, ISBN 0-19-822168-1 .

- Peter Duus : The Abacus and the Sword . The Japanese Penetration of Korea, 1895-1910 . University of California Press , 1995, ISBN 978-0-520-08614-2 (English).

Web links

- "The 1905 Agreement" : The text of the contract is in English under this heading, accessed on December 27, 2009.

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Brian Lee Staff : Painful, significant landmark . In: Korea Joongang Daily . June 23, 2008, accessed May 1, 2019 .

- ^ Duus : The Abacus and the Sword . 1995, p. 189 ( Google Book [accessed May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ a b Shigeki Sakamoto : The validity of the Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty . In: Kansai University review of law and politics . No. 18 , March 1997, p. 59 (English).

- ^ A b archive.org : Full text of "To-morrow in the East" , Douglas Story, Chapman & Hall, Ltd., 1907, p. 108 ff.

- ↑ Shigeki Sakamoto, The validity of the Japan-Korea Protektorate Treaty , in: Kansai University review of law and politics, Volume 18, March 1997, p. 60.

- ↑ Peter Duus, The Abacus and the Sword: The Japanese Penetration of Korea, 1895-1910 , University of California Press, 1995, p. 192 . The translation given here follows the English translation.

- ^ Archive.org : Full text of "To-morrow in the East" , Douglas Story, Chapman & Hall, Ltd., 1907, p. 108.

- ^ Duus : The Abacus and the Sword . 1995, p. 191 ( Google Book [accessed May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ The Chosun Ilbo (English Edition) : Emperor Gojong's Letter to German Kaiser Unearthed ( Memento of February 26, 2009 in the Internet Archive ), published on February 21, 2008, accessed on December 28, 2009.

- ↑ a b Duus : The Abacus and the Sword . 1995, p. 190 ( Google Book [accessed May 1, 2019]).

- ^ Duus : The Abacus and the Sword . 1995, p. 194 ( Google Book [accessed May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ Internet archive.org : Full text of "To-morrow in the East" , Douglas Story, Chapman & Hall, Ltd., 1907, p. 133.