American Volunteer Group

The American Volunteer Group (also Flying Tigers ) was an American squadron in action from April 1941 to July 4, 1942, which consisted of volunteers . It was founded in Kunming (China) in 1941 by then Captain Claire Lee Chennault . The model of this squadron was the first American volunteer air squadron in foreign service, the Escadrille La Fayette flying for France during the First World War - before the USA entered the war .

The name "Flying Tigers" comes from the Chinese commentary on the defense of Kunming against Japanese bombers and was soon officially accepted. The P-40 Tomahawk IIB had a leaping tiger as a standard designation, while they used a wide-open shark's mouth as a " nose art ", which was later copied by numerous other squadrons.

history

Lineup

Chennault resigned from the US Army Air Corps in April 1937, following a request from Song Meiling , wife of the well-known general and later President of the Republic of China , Chiang Kai-shek . He was supposed to examine the Chinese aircraft within three months and work out an expansion plan to increase their ability to fight.

At the time, China was close to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Air Force was under the influence of Italian and American advisers. Ms. Song also headed the Aeronautical Commission to Reorganize the Chinese Air Force .

The official status of Claire Lee Chennault prior to his return to active service for the US Army Air Forces in the spring of 1942 was unclear. He saw himself as a private military advisor to the aeronautical commission. Even when he led the volunteer combat group on missions, his official status was "Advisor to the Central Bank of China" and his passport identified him as a farmer .

Through his work, Chennault laid the foundation for modern aviation logistics, which consisted of strategically placed airfields and an alarm system against enemy approaches. This made it possible in the later years of the Sino-Japanese War to deploy American volunteer airmen from free China as a second front against Japan. These "Flying Tigers" were able to reach 296 kills by Japanese planes from China.

When the Japanese began heavy bombing of Chinese industry in 1939, regardless of civilian casualties, Chennault went back to the United States and asked for assistance with airplanes and volunteers to spearhead the new Chinese air defense. His expanded plans included the expansion of the airfields and logistics for the attack on the Japanese islands. But at the time there were no supporters of his plans.

Even when the Pacific War broke out between Japan and the USA at the end of 1941, no one was enthusiastic about China as a base for an American unit. It was only after the Trident Conference in 1943 that American President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Churchill supported his plans.

The only success of the trip was the recruitment of volunteers and fighter jets for the American volunteer squadron. The planes came from Burdette Wright , then Vice-President of Curtiss-Wright , who was friends with Chennault. The British took over 100 Curtiss P-40s from a French order after the fall of France and put the order on hold at short notice. So the machines could be delivered to China.

commitment

In contrast to Europe , the P-40 in China was superior to the enemy fighters in its flight performance, and the Flying Tigers were able to successfully fight the Ki-27 and Nakajima Ki-43 Hayabusa fighter types, which were mainly used by the Japanese .

In order to fly the machines and maintain them on the ground, however, appropriate personnel were necessary. The US military was absolutely reluctant to volunteer in China. Despite discussions with General Arnold of the Army and Rear Admiral Towers of the Navy, it required direct personal intervention from President Roosevelt, who on April 15, 1941, signed a secret warrant allowing reserve officers to leave the military and volunteer in China . A possible return was also arranged.

The Dutch ship “Jaegersfontaine” left the port of San Francisco on July 10th with the first volunteer pilots and service personnel on board. They were mixed with the other passengers and provided with false papers identifying the men and women as missionaries , merchants , poets or even circus performers.

In total, Chennault recruited 200 ground crew and 100 pilots, 40 from the US Army Air Corps and 60 from the US Marines and the US Navy . The staff were officially employed by the Central Aircraft Manufacturing Company , another, similar grouping. However, never more than 62 pilots and machines were operational at the same time.

The training of the pilots on the Curtiss P-40 took place in Toungoo, Burma . Since many pilots had just signed the China contract, but had relatively few missions, there were a few accidents and crashes at the beginning, none of which resulted in fatalities.

Thanks to a maintenance contract concluded with Curtiss, the machines could also be made airworthy again. This contract included an additional clause that gave the Tigers a $ 500 launch bonus for every Japanese aircraft. The pilots had not been informed of the clause and so only one rumor circulated among the men that the Chinese would pay US $ 500 for every Japanese downed.

While all three squadrons were set up from Burma, two of them were soon relocated to Kunming in China. The third was stationed near Mingaladon near Rangoon . This list later changed several times.

On December 20, 1941, almost two weeks after the USA officially declared war on Japan, the first combat mission took place, in which three Japanese bombers were shot down near Kunming and another was badly damaged. Between December 23 and 25, the third squadron defended Rangoon with 18 planes, and according to its own information, shot down 90 Japanese aircraft, most of them twin-engine bombers. After Rangoon fell, the third season was also relocated to China.

Demobilization

Plans for a bomber group and another fighter unit were dropped after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor , as the US had officially entered the war. The previously "semi-military" structures of the hunting and transport squadrons were subordinated to the newly created 10th Air Force under Clayton Lawerence Bisel and General Joseph Stilwell took over the command for the greater India / Burma / China area . In 1942 the squadrons, initially organized "privately" and financed by Chinese and American funds, gradually became subordinate to the American military ( USAAF ).

The successful hunters against the Japanese were now increasingly required to provide ground air support. This was a task that, from a technical point of view, made little sense due to the performance data of the aircraft, the armament, range and the rather weak armor and represented a high risk for the pilots. At the same time, Chennault's authority was restricted by new, inexperienced superiors, and the more “civil” way of life of the pilots was to be restricted.

Since the pilots had civil contracts and were not yet bound by military discipline and hierarchy, they jointly demanded Chennault's continued command and their use as a fighter squadron in a resolution. All pilots received an offer to join the US Army Air Force, which was largely rejected by them. This was due not least to the fact that most of the pilots came from the US Navy and the US Marine Corps and felt little inclination to join the US Army. Chenault himself was able to achieve a smooth transition into the normal command structures at Bisell and Stilwell, whereby he was offered the leadership of the specially founded 14th AF in the rank of general.

On July 4, 1942, the AVG was dissolved and the Flying Tigers became the regular 23rd Fighter Group . The 1st Pursuit Squadron became the new 74th, and the second and third seasons became the 75th and 76th Fighter Squadron. The 23rd FG took over from the AVG 28 Tomahawks (18 ready to fly), 18 Kittyhawks (17 ready to fly) and 11 Republic P-43 Lancers, which had been borrowed from the Chinese Air Force at the very end of the AVG's service life.

Pilots

One of the most famous pilots of the Flying Tigers was Greg “Pappy” Boyington , who returned to the USMC and directed the famous fighter squadron VMF-214 “Black Sheep” in the Pacific. He scored 26 kills before falling into a prisoner of war after a crash.

Chennault stayed with the army until the end of the war and organized the CAT (Civil Air Transport), a forerunner of Air America , in post-war China .

The German-American pilot Gerhard Neumann ( "Herman the German" ) later became a well-known and successful engine developer.

organization

The Flying Tigers consisted of three seasons ("Squadrons"):

- 1st Pursuit Squadron "Adam & Eves" (body numbers from 1 to 33)

- 2nd Pursuit Squadron "Panda Bears" (34 to 67)

- 3rd Pursuit Squadron "Hells Angels" (68 to 99)

The assignment of the tactical markings to the individual squadrons was only so clear in the first three months, however, later the machines were exchanged between the squadrons at short notice to compensate for losses.

equipment

All three squadrons were initially equipped with Curtiss Hawk 81A-2 , which were designated in the Royal Air Force as Tomahawk IIB. The Tomahawks had no US Army designation, but were referred to as P-40 by the pilots. In 1942 the AVG also found a few P-40E Kittyhawk. There were also the airlift transport aircraft necessary for flight operations → ( The Hump )

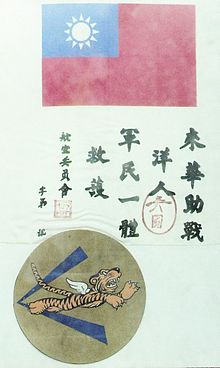

Unconventional in civil life as well as in action, as they were integrated into colonial and Chinese society in the broadest sense. People were casual, uniforms weren't mandatory. The pilots wore a Blood Chit with Chinese lettering on their backs to facilitate communication and rescue after a crash.

Cinematic reception

- The Story of the Flying Tigers , DVD, Fei Hun Films, 1999

- Enterprise Tigersprung ( The Flying Tigers ) (1942), DVD, Republic Studios, director: David Miller , actors: John Wayne , John Carroll u. a.

- Dogfight documentary series from History Channel

literature

- Daniel Ford: Flying Tigers. Claire Chennault and the American Volunteer Group . Smithsonian Books, Washington DC 1995, ISBN 1-56098-541-0 , ( Smithsonian History of Aviation and Spaceflight Series ).

- Maochun Yu: The Dragon's War: Allied Operations and the Fate of China, 1937-1947. Naval Institute Press, 2009. Chapter 3: The flying Tigers with shark's teeth (pp. 24–45)

Web links

- Website of the Flying Tigers (English)

- History of Flying Tigers (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Terrill Clements: American Volunteer Group Colors and Markings , Osprey Aircraft of the Aces No. 41, pp. 64, 95

- ^ Robert F. Dorr: American Volunteer Group - The Flying Tigers , in Wings of Fame, Vol. 9, 1997, p. 10

- ^ Robert F. Dorr: American Volunteer Group - The Flying Tigers , in Wings of Fame, Vol. 9, 1997, p. 5

- ↑ The Story of the Flying Tigers in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- ↑ Flying Tigers in the Internet Movie Database (English)