Battle for Tinian

| date | July 24, 1944 to August 1, 1944 |

|---|---|

| place | Tinian |

| output | Allied occupation of the island |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Harry Schmidt , USMC |

Kiyoshi Ogata, KJA † |

| Troop strength | |

| 35,000 marines 8 aircraft carriers 6 battleships 3 heavy cruisers 3 light cruisers 16 destroyers 358 aircraft |

3,929 Army soldiers 950 Marines 3,160 Marines |

| losses | |

|

390 dead |

7,800 dead, |

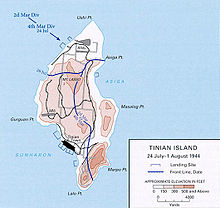

The Battle of Tinian (code name Operation Forager, Phase III ) was an American landing operation as part of the conquest of the Mariana Islands during the Pacific War in World War II . On July 24, 1944 6,000 soldiers of the 5th Amphibious Corps landed on the Mariana Island of Tinian with 200 amphibious tanks . The island was defended by 8,050 Japanese soldiers. The American marines were finally able to break the enemy resistance on July 28th, and Tinian was considered secure from August 1st, although isolated Japanese soldiers continued to fight.

By conquering Tinian and the other Mariana Islands, the US forces wanted to cut the transport routes from Japan to the occupied territories of the Japanese in the southern Pacific and in Southeast Asia by attacking the Japanese ship convoys from land-based US aircraft. In addition, Boeing B-29 bombers from the Mariana Islands were supposed to carry out air strikes on Japanese cities. The US troops were able to implement both goals after the conquest of the Mariana Islands.

prehistory

Japanese location

The small island of Tinian is located in the northern Mariana Islands. It was part of the German New Guinea colony from 1899 to 1918 . Tinian was occupied by smaller Japanese units during the First World War in 1914 . In 1918 Japan was granted Tinian as a mandate by the League of Nations . Japanese troops built a larger airfield with four runways at Ushi Point in 1931 , as the island was of strategic importance for the control of this area of the Pacific. In 1940 22 aircraft of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Force were stationed on the airfield .

In March 1944, 3,215 Japanese soldiers of the 50th Infantry Regiment of the 29th Infantry Division of the 31st Army were relocated from Manchuria to Tinian. The 50th regiment was a battle-tested unit. It consisted of three battalions of around 880 soldiers each, plus a battalion with twelve 75 mm infantry guns, a tank company with twelve light tanks of the type 95 Ha-Go and a battery with light 47 mm anti-tank guns .

The 50th Infantry Regiment and the other army troops were under the command of Colonel Kiyoshi Ogata from March 1943 . Ogata also had supreme command of the entire defense of Tinian. In October 1943 he was also assigned 714 men from the 1st Infantry Battalion of the 135th Regiment, which was stuck on Tinian after an exercise and could no longer be shipped back to the Truk naval base due to a lack of transport ships .

From May 12, 1943, 2,349 marines from the 3rd Special Base Unit ( 第 3 特別 根 拠 地 隊 , Dai-3 Tokubetsu Konkyochitai ) and 950 marines from the 56th Marine Guard , who had been transferred from Truk , were on the island . These soldiers were under the orders of Kaigun-Taisa (= sea captain ) Goichi Oya . The navy troops took over the defense of the airfields, as these belonged to the facilities of the naval aviation. The Japanese marines also took over all the heavy artillery pieces around the runways and the 39 heavy anti-aircraft guns that had been set up immediately around the runways. There were also construction crews, aeronautical and staff personnel, so that a total of around 4,110 soldiers from various units defended the airfields. 49 other naval aircraft were also flown in. There were 13 Aichi D3A , 24 Mitsubishi A6M and twelve Mitsubishi G4M .

Vice Admiral Kakuta Kakuji was the highest-ranking Japanese naval officer on Tinian and commander of the 1st Air Fleet, which in 1943 consisted of around 400 aircraft spread across the Pacific on various islands. In June 1944, after several battles, the 1st Air Fleet only consisted of twelve machines. Admiral Kakuta had established his headquarters on Tinian in March 1944, but exercised no authority over the army troops on the island, and the naval troops were not under his direct command either.

In October 1943, the Tōjō cabinet ordered all Japanese bases in the Pacific Ocean to be fortified in view of an American invasion. Colonel Obata then ordered the construction of about 300 defensive bunkers in his field order No. 233 . From October 30, 1943, the defenses were built on the island, mostly by Korean and Chinese slave labor . The first of the planned three lines of defense ran along the beach, the second two kilometers further inland, while the third could not be built due to a lack of cement . By the start of the American landings on Tinian, the various defensive structures, mainly bunkers, anti-tank traps, artillery battery positions, trenches, individual cover holes, tank traps and machine-gun nests, were only 20 to 40 percent complete. The defenses had been expanded against a landing near the town of Tinan, as the beach and the gap in the coral reef there was wide enough for larger amphibian groups to land at the same time.

Strategically, the Mariana Islands held a key position for Japan on the sea routes from Borneo and Sumatra , on which oil essential to the war effort was transported to Japan. The archipelago was also a source of supplies for the Japanese war industry, especially linen . It was therefore crucial for the Japanese to keep Tinian and the other Mariana Islands under their control, since from there the American troops could cut off the Japanese units in the southern Pacific from Japan and the raw material supplies to Japan.

American location

According to the plans of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 1943, the two American offensive formations in the Pacific under General Douglas MacArthur and Admiral Chester W. Nimitz should proceed with different thrusts. MacArthur's troops, supported by units of the Australian Army , were to be the first to recapture the Japanese-occupied parts of New Guinea and to advance against the Philippines from May 1944 . The troops under Admiral Nimitz, on the other hand, were to conquer the Marianas and other islands. In addition to its fleet, Nimitz had marine and army units that land on the islands and conquer them.

The main objective behind the planned occupation of the Mariana Islands was to cut off supply routes from Japan to the Japanese occupied territories in the southern Pacific and Southeast Asia. In addition, land-based US aircraft from the Mariana Islands were able to attack Japanese ship convoys and carry out air strikes on Japanese cities. Although the two commanders in chief of the US forces, Nimitz and MacArthur, had voted against the occupation of the Mariana Islands, the commander in chief, Admiral Ernest J. King , insisted on their capture.

Rear Admiral Harry W. Hill had received on 5 July 1944 by Admiral Nimitz ordered to conduct the operation against Tinian. The forces available to Admiral Hill to land on Tinian consisted of parts of the 5th Amphibious Corps. These included parts of the 2nd and 4th US Marine Division . This force consisted of battle-hardened soldiers who had fought on Guadalcanal , Tarawa and Kwajalein . The troops were led by Lieutenant General Harry Schmidt and formed the core of the landing force. During the invasion of Saipan , the northern neighboring island of Tinian, from June 15 to July 9, the 2nd Marine Division, under the command of Maj. Thomas E. Watson, and the 4th Marine Division, under the command of Maj. Clifton B. Cates suffered very heavy losses. The two divisions had been decimated from a nominal strength of 50,000 men to around 35,000 soldiers. Despite the losses, parts of these two divisions were supposed to land on Tinian. In addition, the landing formations were supplemented by the 708th Amphibious Tank Battalion, a battalion of engineers of the United States Army and a Seabees battalion. In support of the landing, two artillery battalions had taken up position on the southern tip of the neighboring island of Saipan, in order to fire on the enemy positions from this position. The two artillery battalions had 168 guns of caliber 105 mm and 155 mm.

The United States Air Force had the 48th bomber squadron, equipped with B-25 bombers, stationed on Saipan. In addition there were the P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bombers of the 7th Air Fleet and seven P-61-Black Widow - night fighters for night missions. These planes were supposed to assist the landing with air strikes. Various carrier aircraft from Task Force 58 were also to make strategic pre-launch attacks.

preparation

In early June 1944, Tinian, Saipan and Guam were bombed from sea for the first time. The American plan for the invasion of the Mariana Islands called for heavy preparatory air strikes by 340 B-24 Liberator bombers of the 7th Air Force , which launched from the bases of the Marshall Islands 2,000 km to the east . These bombers were supported by F4U Corsair and F6F-Hellcat - aircraft carrier fighters and fighter-bombers , as well as land-based aircraft that took off from the Tarawa military airfield . Carrier aircraft were launched from eight aircraft carriers. It became Task Group 58.4 under the command of Rear Admiral Gerald F. Bogan with the carriers USS Essex (CV-9) , USS Langley (CVL-27) and USS Princeton (CVL-23) and Task Group 52.14 under the command of Rear Admiral Harold B. Sallada with the carriers USS Midway (CVE-63) , USS Nehenta Bay (CVE-74) , USS Gambier Bay (CVE-73) , USS Kitkun Bay (CVE-71) and USS White Plains (CVE-66) used. After air superiority was achieved , these air strikes were to be stopped and preparations by ship artillery fire continued. In addition to the eight aircraft carriers, the Navy provided 27 combat ships. Among the warships were 16 destroyers , six battleships , three heavy cruisers and three light cruisers . These were the battleships USS Colorado , USS Pennsylvania , USS Massachusetts , USS New Mexico , USS South Dakota and USS New Jersey . The heavy cruisers USS Indianapolis (CA-35) , USS Louisville (CA-28) and USS New Orleans (CA-32) , as well as the light cruisers USS Cleveland (CL-55) , USS Montpelier (CL-57) and USS Birmingham (CL-62) . These combat ships fired a total of 100,000 grenades at Tinian, which, among other things, destroyed beach bunkers. The Japanese casualties totaled 321 men. The approximately 100 km² island could be seen almost completely from the sea and from the air. The island was attacked for over 43 days by American warships and aircraft of the VII Air Force. The reconnaissance of the USAAF made it possible for the American fleet off the island not only to bomb all recognized positions of the enemy, but also to systematically fire at sections of terrain that appeared suspicious or tactically decisive. Around 60 fighter-bombers also dropped napalm bombs in the course of the preparatory attacks .

When American troops occupied the northern neighboring island of Aguijan , around 8 km away, after the Battle of Saipan at the beginning of July 1944 and controlled both the sea routes and the air space around Tinian, the Japanese garrison was effectively enclosed on the island. The 107 Japanese naval aircraft stationed on Tinian had already been shot down on June 19, 1944, shortly before the battle in the Philippine Sea , during a preparatory attack by the USAAF.

The plans for landing on the island focused on two options: the landing near the town of Tinian, which was planned to be carried out by troops of the 2nd Marine Division, or the landing at the White Beaches , the smaller beaches on the north side of the island, who were not very well prepared for a defense after American reconnaissance flights. The landing near the town of Tinian in the southwest of the island, at the port of Suharon, had the advantage that the beach and the gap there in the coral reef around the island were wide enough for the simultaneous arrival of larger groups of amphibians, but this was also obvious to the defenders . The American intelligence then also confirmed the prepared positions and construction activities of Japanese troops in this area. The White Beaches in the north of the island were less suitable for a landing. There was a risk of losing landing craft and amphibious tanks in accidents on coral reefs in the water. There were also dead coral reefs right on the beach that Amtracs and tanks could not run over. There were two decisive advantages in favor of this company. The American artillery pieces on Saipan could give the landing troops fire protection and on the other hand the Japanese did not expect a landing in this area and their defense there was accordingly much weaker, as pictures of the American reconnaissance planes showed. At a meeting of the commanders of the operation, led by Admiral Raymond Spruance , the decision was made to land at the White Beaches . The two coastal stretches of the landing were named White Beach I and White Beach II .

On July 23, the day before the scheduled landing, the area around the town of Tinian was again heavily shelled by the warships off the island. About 3,000 shells, up to 380 mm calibers , completely destroyed the city and continued to create the impression that the main attack would take place here. Colonel Ogata concentrated almost all available guns and most of the Japanese troops in the vicinity of the city that day. Ogata had his soldiers set up numerous fortified and camouflaged positions around the city. Ogata had also drawn up various plans for possible US landings in the southwest and northwest of the island. He recognized White Beach II as a possible landing site and had it secured with hundreds of mines and a smaller infantry unit of the 50th Regiment. Ogata himself was in his command post on Mount Lasso, 171 meters high, the highest point on Tinian. A Japanese unit, the 1st Battalion of the 135th Regiment, was supposed to attack the beach section in question immediately in the event of a landing and, if possible, overrun the enemy with a Gyokusai attack (= suicide attack) before he could reorganize himself after leaving the landing craft. The bulk of Ogata's troops should be limited to the defense of the interior and offer resistance during the day, while his troops should withdraw to other positions in the dark. The US Air Force and Navy Air Force attacked with more than 350 aircraft throughout the day. They bombed the Japanese positions, attacking some of them at low altitude, dropping 500 bombs and 42 incendiary bombs . There were also 200 air-to-surface missiles that were fired by the F4U Corsair fighter-bombers against bunkers or caves. Finally, several P-47 fighter-bombers were used from Isely Field on Saipan, which dropped napalm bombs on Tinian again.

Course of the battle

landing

In the early morning of July 23, 1944, the landing fleet set course for Tinian. This fleet included 6 transport ships , 3 Liberty ships , 2 LSD , 37 LST , 31 LCI , 20 LCT , 92 LCM , 12 LSM and 70 LVT (also called Amtracs). On the afternoon of July 23, the mission ships with the landing units of the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions, which were under the command of General Harry Schmidt, anchored about nine kilometers from the two White Beaches of Tinian. At around 2:00 a.m. on July 24, the soldiers boarded the landing craft and Amtracs, which were heading for the designated landing points. At 2:30 a.m., the battleships and heavy cruisers opened fire on the beaches for 30 minutes, destroying several defenses that were still intact. Meanwhile, destroyers were approaching the coast to continue firing on selected targets inland. Several sea mines were removed by minesweepers . P-47 fighter-bombers launched from Isley Field on Saipan bombed the White Beaches with napalm bombs. Since a Japanese resistance in the landing area was not expected, the further planned flight operations of the fighter-bombers could be canceled. At 4:00 am, the 70 Amtracs, manned by around 5,000 soldiers from the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions, reached the two White Beaches . The troops were supported by units of the 24th Marine Regiment , which had been driven to White Beach I from the southern tip of Saipan in LST and DUKW amphibious vehicles. Two Amtracs were lost because of the coral reefs around the beach. The other Amtracs made it safely to just before the reef edge on the beach. Now the marines had to wade ashore because the Amtracs could not cross the reef edge on the beach. No sign of resistance was reported. A little later, the 25th Marine Regiment landed at White Beach II , but this time the amphibious vehicles ran into a minefield, and two more Amtracs were destroyed. The soldiers of the 25th regiment went ashore and came under fire from infantry weapons. The enemy defensive positions were quickly identified and destroyed in close combat, including the use of hand grenades. The units of the 25th Regiment had a few failures.

Japanese counterattacks

Two regiments of the 2nd Marine Division carried out a deception off the town of Tinian during the landing operations on the White Beaches in order to retain the defenders of the island in this area. Colonel Ogata thereupon ordered the still operational heavy artillery pieces, which were stationed on the headland Faibus San Hilo , to bombard the warships and landing craft in front of the city. The Japanese artillery had not yet been used so as not to reveal their position. At 6:00 am, Japanese guns began firing at the 20 offshore DropShips and supporting warships from two captured British 6- inch guns, twelve 100mm guns and three 150mm howitzers . The battleship USS Colorado , which had come within three kilometers of the coast to fire on selected targets inland, was hit by 22 shells within 15 minutes. The shells hit the navigating bridge area in rapid succession. 42 seamen and 2 officers were killed, while 198 others were wounded. The destroyer USS Norman Scott also received six shell hits. The commander and 23 seamen were killed, and 25 seamen were wounded.

The Seabees of the 4th Marine Division built along the way, supported by a battalion of the army, different landing ramps to overcome the reef at the landing beach White Beach I . These ramps made it easier to set down and land amphibious tanks, artillery pieces and other heavy vehicles that were brought to the beach by three LSTs. Transportable landing ramps were also used and bulldozers leveled the coral reef edge on the landing beach. Around 65 M4 Sherman tanks, 15 of which were equipped with flamethrowers , and several M3 half-tracks also landed on that day . A total of 15,614 soldiers were brought ashore that day. After the landing ramps were built, two pontoon piers were installed in order to bring weapons and equipment ashore from larger ships. These two pontoon piers were destroyed in a storm on the night of July 29th to 30th. An LVT ship was pushed aground by a wave and later had to be towed free.

Meanwhile, several platoons of the 2nd Division had advanced far inland without encountering strong Japanese resistance. Only at 12:00 noon did a detachment of Japanese soldiers from the 50th regiment attack the right flank of the American bridgehead. These troops were wiped out by machine gun fire, killing 134 Japanese and 12 US Marines. On the evening of July 24, the first American units had advanced 1.3 kilometers inland and the Seabees set up a first line of defense at 7:00 p.m.

Given the rapid advance of the American units in the north of the island, Colonel Ogata ordered a counterattack. The army troops of the 135th Regiment, supported by ten Ha-Go tanks and a battery of 75 mm guns, were to carry out the planned counterattack at 2:00 a.m. on the night of July 24th to 25th. A night attack should be carried out, as troop movements in daylight were impossible due to ship artillery fire and air strikes. The 714 soldiers of the 135th regiment were led by Captain Izumi. Izumi's units launched the attack after several soundings. That night, Izumi's unit advanced nine kilometers against the center of American forces. They tried to push in the enemy beachhead at the interface between the troops of the 24th and 25th US Marine Regiment of the 2nd Marine Division by a storm attack. The attack was halted by artillery and machine gun fire, almost completely wiping out the Japanese forces. The American artillery bombardment lasted three hours and killed 632 men of the 135th regiment. Five Japanese tanks were also destroyed. 600 Japanese marines of the 56th Marine Guard under the command of Sea Captain Goichi Oya had attacked the left flank of the American line of defense at the same time. This attack was also stopped, with the Japanese troops losing 476 soldiers. At 5:00 a.m. on July 25, an attack by six Japanese tanks, which advanced against the positions of the US Marines without infantry or artillery support, was also halted. Two American 37mm PaK batteries destroyed two of the Japanese tanks. Another three tanks were hit by bazookas and also destroyed. The total casualties of the Japanese after the night raids ended at 1,241 soldiers killed, while the Americans lost 104 men. Colonel Ogata withdrew the remaining troops of the 50th regiment inland. It was decided in a staff meeting on July 26th to restrict the defense from now on only to holding back resistance and minor counter-attacks.

Advance

On July 26, the American Marines of the 2nd Division began the advance towards the city of Tinian, with several platoons advancing far inland without Japanese resistance. On the evening of July 26th, units of the 25th Marine Infantry Regiment reached the east coast of Tinian. On the morning of July 28, the first American units, units of the 4th Marine Division, had already advanced within 2 kilometers of the city of Tinian. At 5:00 am on July 29, units of the 24th Marine Regiment reached the city without encountering any Japanese resistance. As planned, when the marines reached the first districts of the city, the shelling of the city center began, where numerous enemy positions were suspected. However, the bombardment did not start at 6:00 a.m. as planned, but around 2 hours later. Due to the Japanese fortifications in front of the city burning under heavy smoke, the orientation of the artillery units was very difficult. Therefore, destroyers had to be used, which were anchored off the coast and hit the city from the west under heavy fire. On that day, the destroyers also fired phosphorus grenades at the sugar cane plantations to set them on fire. By burning the sugar cane fields, the US troops wanted to deprive the Japanese units of a possible cover. The bombardment stopped after four hours. The first units of the 24th Regiment entered the city center without significant resistance, although booby traps and isolated gunfire killed some US soldiers. At around 4 p.m. the city center was finally occupied. When proceeding further, the marines occupied airfield No. 4 near the city and got caught in a fire attack by Japanese troops. About 400 soldiers of the 50th regiment, supported by a mortar battery, attacked the units of the 2nd Marine Division, but these attacks were crushed by machine gun fire and flamethrower use. An American tank company attacked the last Japanese troops in the vicinity of the airfield in the afternoon. An M4 Sherman tank was destroyed in this attack. The American soldiers occupied around 80% of the island of Tinian by the end of the day, with no Japanese resistance. The southern part of the island was still unoccupied by US troops, a mountainous, forested and difficult to access area. In this part of Tinian, the majority of the defenders, around 1,200 men of the 50th regiment and 900 Japanese marines, had withdrawn on the orders of Colonel Ogata. These soldiers holed up in a cave and bunker system.

On the orders of General Schmidt, this area was attacked by ship artillery and aircraft. For one day, the southern part of the island was bombarded by warships with a total of around 615 tons of shells, while 65 aircraft stationed on Saipan dropped around 69 tons of explosive and incendiary bombs. The American land artillery also fired 300 tons of grenades on the suspected enemy positions in the mountains that day. The following infantry attack on the Japanese positions in the hills resulted in losses despite the heavy artillery preparation. Three American M4 Sherman tanks were lost to enemy fire from 47mm anti-tank guns and infantry attacks by Japanese soldiers using detention mines . The American troops of the 2nd Marine Infantry Division had to conquer the numerous caves one by one, using so-called corkscrew teams . These were combat groups of five Marines each, armed with flamethrowers, hand grenades and explosives, which were supposed to attack each cave individually and bring down its entrances with explosives. Japanese troops attacked American units several times, but they were thrown back. About 400 Japanese defenses were captured on July 29 and 30, killing around 100 US Marines. Despite the heavy losses, the morale of the Japanese troops was rated as "excellent" by Colonel Ogata in a radio message at that time. However, the combat strength of the units decreased rapidly due to a lack of supplies and high losses. The US Marines of the 2nd Division, after having reached the summit of the highest plateau of Tinian with two battalions and a tank unit, were picked up by the last major Japanese unit of 600 to 800 soldiers of the 50th regiment at 11:00 p.m. attacked. This attack was shot down by the Marines using heavy artillery and machine gun fire before Japanese forces could reach the American lines. About 680 Japanese and 20 US marines died.

End of battle

Vice Admiral Kakuta, who had established his command post in a cave on Tinian's east coast, sent a final radio message to the Imperial Army Headquarters in Tokyo on July 29 . In the radio message he reported the destruction of all secret records and documents. He then announced that a Gyokusai attack (suicide attack) by all Japanese army and naval troops on Tinian was imminent and that this was probably his last radio message. On the evening of July 30th, the last suicide attack started with 400 soldiers from the 50th regiment and about 600 marines from the 3rd special base unit. The Japanese troops attempted to push in the right flank of the American front line, supported by machine gun and mortar fire. However, at 1:00 a.m., the Japanese units were stopped by artillery fire. Shortly thereafter, the US Marines launched a counterattack supported by flamethrower tanks. As a result of this counterattack, the Japanese troops were dispersed and Colonel Ogata, who led the Japanese attack, was killed. After the American counterattack, only smaller Japanese combat groups occupied the road that led to the plateau. They also attacked from the flank. In doing so, they blocked the road and destroyed two US tanks. At 5:15 a.m. on July 31st, the last Japanese attack on American troops on the plateau took place, ending after a 30-minute hand-to-hand combat. In the suicide attacks on the night of July 30th to 31st, around 800 Japanese soldiers were killed and 49 American marines lost their lives.

Tinian was declared secure by Lieutenant General Harry Schmidt on August 1, 1944 at 6:55 p.m. On the following day, however, there was a last uncoordinated attack by 200 dispersed Japanese soldiers, which was repulsed by the marines of the 4th Division with minor losses of their own. The two remaining Japanese commanders Goichi Oya and Kakuji Kakuta died on August 2nd from seppuku , a ritualized form of suicide . Attacks by small groups of Japanese soldiers dragged on for months and by January 1, 1945 led to the deaths of 38 American soldiers and chamorro police officers from the Tinian Island Command and 542 Japanese soldiers.

Murata Susumu was the last Japanese soldier to be captured in 1953. Since the war, Murata Susumu lived as a holdout in a small hut near a swamp.

losses

Of around 15,000 Japanese, Korean, Chinese and Chamorro civilians on Tinian before landing, around 4,000 must have perished. They died in the American preparatory attacks and the fighting on the island. Civilians also committed suicide or were killed by Japanese soldiers. It is reported that Japanese soldiers grouped civilians and blew them up with hand grenades, although it is unclear whether the civilians voluntarily chose to die. On other islands of the Mariana Islands, Japanese troops committed war crimes before the landing and during the fighting against Chamorros, the indigenous people of the Mariana Islands. In contrast to the other Mariana Islands, war crimes committed by US troops for use on Tinian are not documented. All of the approximately 11,000 surviving civilians on the island were interned by the American occupation forces in a prisoner-of-war camp in the center of the island and guarded by 200 soldiers. Also on the subject of civilians on Tinian, unlike on other Mariana Islands, no more detailed studies or data are available so far.

American casualties amounted to 328 soldiers killed, including 317 Marines from 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions. 62 sailors were also killed on the two warships USS Colorado and USS Norman Scott . 1,593 Marines and sailors were wounded during the fighting on the island.

Of the 8,052 Japanese soldiers pre-US attack on Tinian, only 252 were captured. 7,800 Japanese soldiers must have perished during the fighting. About 5,000 bodies of Japanese soldiers were buried by US forces. Accordingly, the bodies of about 2,800 Japanese were not found by US troops. These remaining Japanese or their corpses were buried during the fighting in the caves and bunkers during explosions, artillery fire or bombs, others were torn to pieces or burned.

Consequences of the battle

Two of the Japanese airports ( North Field ) on Tinian were repaired and expanded by the Americans in February 1945, while another four landing and runways were built by the two Seabeebatallons ( West Field ). Tinian airfields were taken over by USAAF in February 1945. From March 1945 the 58th Air Division of the XXI Bomber Command , XX Air Force was stationed on Tinian. The airfields on Tinian, Saipan and Guam served primarily as a base for Boeing B-29 bombers, which attacked mainland Japan from September 1944 . From February 1945, the 58th Air Division also flew missions against the islands of Truk, Iwojima and Chichi-jima . In November 1944 and January 1945, Japanese bombers flew attacks against the American airfields in the Mariana Islands from Japan, with eleven B-29s being destroyed. From March 1945 B-29 bombers stationed on Tinian flew mine-laying operations in the waters around the Japanese main islands on every full moon night as part of the campaign against Japanese shipping, with the Kammon Strait in particular being mined. On March 9, 1945 , the B-29 bombers attacked Tokyo , destroying most of the city with incendiary bombs. On August 6, 1945, the B-29 " Enola Gay " took off from North Field Airfield to drop the atomic bomb on Hiroshima . Just three days later, on August 9, 1945, the B-29 “ Bockscar ” also took off from this military airfield with an atomic bomb on board towards Nagasaki .

literature

- Campaign in the Marianas. In: Philip A. Crowl: United States Army in World War II - The War In The Pacific. Office of the Chief of Military History, US army, 1970.

- Richard Fuller: Japanese Generals 1926–1945. 1st edition. Schiffer Publishing Ltd., Atglen, PA 2011, ISBN 978-0-7643-3754-3 .

- Saburō Ienaga: The Pacific War - World War II and the Japanese, 1931-1945. Pantheon Books, New York 1978, ISBN 0-394-73496-3 .

- Daniel Marston: The Pacific War Companion: From Pearl Harbor to Hiroshima. Osprey Publishing, 2007, ISBN 978-1-84603-212-7 .

- John T. Mason: The Pacific War Remembered: An Oral History Collection. US Naval Institute Press, 2003, ISBN 1-59114-478-7 .

- Bernard Millot: The Pacific War. BUR, Montreuil, 1967.

- Samuel Eliot Morison : New Guinea and the Marianas: March 1944 - August 1944: History of United States Naval Operation During World War II - Volume 8. University of Illinois Press, 2002, ISBN 0-252-07038-0 .

- Recherche International eV (ed.): "Our victims don't count" - The Third World in World War II. Recherche International eV, Berlin / Hamburg 2009. ISBN 3-935936-26-5 .

- Gordon Rottman: Saipan & Tinian 1944: Piercing the Japanese Empire. Osprey Publishing, 2004, ISBN 1-84176-804-9 .

- Stanley Sandler: World War II in the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. ( Military History of the United States. ), Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-8153-1883-5 .

- HP Willmott and Ned Willmott: The Second World War in the Far East. ( Smithsonian History of Warfare. ) HarperCollins, 2004, ISBN 978-0-06-114206-2 .

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ D. Colt Denfeld: Hold the Marianas: the Japanese defense of the Mariana Islands. White Mane Pub, 1997, ISBN 1-57249-014-4 , p. 105.

- ↑ The Japanese rank Taisa corresponds to the German rank of captain at sea , since the prefix Kaigun indicates that it is a naval officer.

- ^ A b c d Campaign in the Marianas. P. 279.

- ↑ Elmer Belmont Potter: Nimitz. US Naval Institute Press, 1976, ISBN 0-87021-492-6 , pp. 279ff.

- ^ WF Craven, JL Gate: The Army Air Forces in World War II Volume Four - The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan - August 1942 to July 1944. The University of Chicago Press, 1950, pp. 691ff.

- ↑ D. Colt Denfeld: Hold the Marianas: the Japanese defense of the Mariana Islands. White Mane Pub, 1997, ISBN 1-57249-014-4 , p. 133.

- ^ Gordon Rottman: Saipan & Tinian 1944: Piercing the Japanese Empire. Osprey Publishing, 2004, p. 72.

- ↑ a b c Bernard Millot: The Pacific War. 1967, p. 700.

- ^ A b Gordon Rottman: Saipan & Tinian 1944: Piercing the Japanese Empire. Osprey Publishing, 2004, p. 73.

- ^ Bernard Millot: The Pacific War. 1967, p. 670.

- ^ Gordon Rottman: Saipan & Tinian 1944: Piercing the Japanese Empire. Osprey Publishing, 2004, p. 31.

- ^ A b Bernard Millot: The Pacific War. 1967, p. 701.

- ^ A b c Gordon Rottman: Saipan & Tinian 1944: Piercing the Japanese Empire. Osprey Publishing, 2004, p. 75.

- ↑ a b USMC report. on Ibiblio, sighted August 30, 2010

- ^ Gordon Rottman: Saipan & Tinian 1944: Piercing the Japanese Empire. Osprey Publishing, 2004, p. 77.

- ^ Edwin Palmer Hoyt: To the Marianas: war in the central Pacific - 1944. Ave Books, 1989, ISBN 0-380-65839-9 , p. 220.

- ^ Gordon Rottman: Saipan & Tinian 1944: Piercing the Japanese Empire. Osprey Publishing, 2004, p. 20.

- ^ Edwin Palmer Hoyt: To the Marianas: war in the central Pacific - 1944. Ave Books, 1989, ISBN 0-380-65839-9 , p. 223.

- ^ USMC report. on Ibiblio, pp. 85-91, viewed June 16, 2012

- ^ Gordon Rottman: Saipan & Tinian 1944: Piercing the Japanese Empire. Osprey Publishing, 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Edwin Palmer Hoyt: To the Marianas: war in the central Pacific - 1944. Ave Books, 1989, ISBN 0-380-65839-9 , p. 225.

- ^ In Campaign in the Marianas. On p. 279 the name is translated as "Isumi"

- ^ Gordon Rottman: Saipan & Tinian 1944: Piercing the Japanese Empire. Osprey Publishing, 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Gordon Rottman: Saipan & Tinian 1944: Piercing the Japanese Empire. Osprey Publishing, 2004, p. 76.

- ^ Bernard Millot: The Pacific War. 1967, p. 703.

- ^ Gordon Rottman: Saipan & Tinian 1944: Piercing the Japanese Empire. Osprey Publishing, 2004, p. 79.

- ^ Gordon Rottman: Saipan & Tinian 1944: Piercing the Japanese Empire. Osprey Publishing, 2004, pp. 80-81.

- ↑ a b c d e f g USMC report. on Ibiblio

- ^ Gordon Rottman: Saipan & Tinian 1944: Piercing the Japanese Empire. Osprey Publishing, 2004, p. 82.

- ^ Gordon Rottman: Saipan & Tinian 1944: Piercing the Japanese Empire. Osprey Publishing, 2004, p. 85.

- ^ History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. P. 357.

- ↑ Other sources report that he was seen on August 2nd and then committed suicide, for example in: History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. P. 369. - Other reports say that he was hit by a shell in his command post was killed so in Frank O. Hough: The Island: The United States Marine Corps in the Pacific. P. 255.

- ^ Gordon Rottman: Saipan & Tinian 1944: Piercing the Japanese Empire. Osprey Publishing, 2004, p. 87.

- ^ Bernard Millot: The Pacific War. 1967, p. 704.

- ^ Campaign in the Marianas. P. 303.

- ↑ Bruce M. Petty: Saipan: Oral Histories of the Pacific War. McFarland & Company, Jefferson 2002, p. 40.

- ^ Recherche International eV (ed.): “Our victims don't count”. 2009. p. 393.

- ^ Recherche International eV (ed.): Our victims do not count. 2009. Section Fight to the Death - Final Skirmishes and War Crimes. Pp. 390-394.

- ^ A b c Gordon Rottman: Saipan & Tinian 1944: Piercing the Japanese Empire. Osprey Publishing, 2004, p. 89.

- ↑ List of losses. on Ibibilo, sighted August 30, 2010