The epiphany

The epitome is a cycle of novels by the Swiss poet Gottfried Keller . Keller wrote down his first ideas for the work in Berlin in 1851, where he also put the opening chapters on paper in 1855. Most of the text, however, was not written in Zurich until 1881, while the preprint was already being made in the Deutsche Rundschau . An expanded book version followed at the end of the year.

The cycle is named after a symbolic poem ( epigram ) by the Baroque poet Friedrich von Logau , which plays a role in it. It reads: “How do you want to turn white lilies into red roses? / Kiss a white Galathee: she will laugh reddeningly! ” Galateia , (Galatea, Galathée), the most beautiful of the daughters of the sea god Nereus , has long been considered the embodiment of the exciting, but at the same time restraining effect of female beauty on male desire. In the spirit of gallant poetry , Friedrich von Logau turned to young cavaliers and advised them “through the flower” not to allow too strict reins to be put on them. Poets and public of the 19th century also associated the name Galathee with Ovid's metamorphosis tale by the artist Pygmalion , who, for lack of a lovable companion, creates an ivory statue for himself, whereupon the gods have mercy on him and the image come to life under his kiss.

The seven epigram -Novellen, each a happy or unhappy love choice as its theme are in a frame narrative woven, which itself is a love novel. This takes place in Germany in the 1850s in the romantic setting of a university town. From there on a fine June morning the young naturalist Mr. Reinhart rides out to make - as he calls it - scientific observations. In the evening he reaches the country residence of the book-loving and linguistic Lucie high above the valley. Herr Reinhart is enchanted by the beauty and wit of his hostess; at the same time he feels challenged by their intellectual independence. In this mood, he tells her the Logausche epiphany, which he uses as an erotic travel guide and guide to kissing experiments. When he also gave the best of the experiences he had gathered during the day - one just laughed while kissing, another just blushed, with a third he broke off the attempt - the angry Lucie punishes him with the story of a foolish person who sneaked into it Kissing makes you unhappy. With this, she opens a dispute based on example narratives, which revolves around the spiritual equality of men and women as a prerequisite for happy marriages. To Lucie's delight, Reinhart turns out to be not a heartbreaker , but a fateful narrator; to their annoyance, he only lets the heroes of his stories make happy choices when they bond with humble, subservient women. Lucie's uncle, an old cavalry colonel, contributed a personal experience and gave Reinhart's belief in male freedom of choice in love a heavy blow. Once again, the guest strikes back and impresses with the story of a Portuguese navigator who literally picks up his future wife, an African slave, from the ground. But Lucie counters elegantly with a young Indian woman who steals the trophies of his heartbreaking career from a French officer. Disarmed, the researcher clears the field, but returns - and now the affection of the two quickly grows beyond friendship and flares up as a great love. At the kiss, Lucie blushes and laughs: the Logausche epigram has proven itself.

The epitome gave Keller the greatest success of his writing career with contemporary readership and literary criticism. Several editions appeared in quick succession. Reviewers certified the author's classic format and placed the work on the side of the Decamerone . Literary historians praised the interweaving of the framework and internal narratives as being uniquely artistic. The latter was later also disputed: The change in literary taste that occurred in the 20th century made it difficult for readers and critics to access a work whose author seemed to be deliberately avoiding modern topics. The fact that the narrative actually unfolds a broad spectrum of such topics, among them as topical as the relationship between the sexes and the relationship between natural sciences and humanities (" two cultures "), only became clear from the 1960s, when literary studies dealt with narrative theory , Gender studies , discourse analysis , history of science opened up new research areas. Because of its variety of topics, the cycle places high demands on the performers. Above all, the question of Keller's attitude towards women's emancipation and scientific progress calls for controversial interpretations. Most of the performers agree on the high literary quality of the work.

Keller divided the text into thirteen chapters. From the seventh to the twelfth these are headed with the title of the novella that is told in it. Before and at the end, the headings announce what is going on in the chapter. This trick, based on the model of Cervantes ' Don Quixote , bathes Mr. Reinhart's undertaking in a cheerfully ironic light. The frame story is told from the perspective of the main male character throughout. The traveling naturalist initially sees his kissing adventure as steps in a series of scientific experiments, but does not take himself as seriously as his distant role model.

content

A naturalist discovers a process and rides across the country to test the same

Mr. Reinhart's day's work begins with the darkening of his study. From the whole beautiful summer morning only a thin beam of light is allowed to enter through a small hole in the shutter, and then to be directed through crystals, whose construction secrets it is supposed to clear up. But as soon as Reinhart looks into the tube, a stabbing pain reminds him of how badly this work damages his eyes. While he thinks about what is good to see and hear with healthy senses - the female figure and voice, for example - he has the feeling that with the dawn he has shut out the world and people and is missing life through his science. Startled, he pushes the shutters open again and looks for one of the books that deal with half-forgotten human things . When he opens it, his gaze falls on the Logausche epigram:

How are you going to turn white lilies into red roses?

Kiss a beautiful Galathee, she will laugh and blush!

“What a delicious experiment!” He exclaims. “That's how it has to be: laughing and blushing!” He notes down the recipe and puts the slip of paper in his wallet. Then he gets ready to travel, rents a horse and leaves town, determined not to return until he has succeeded in the tempting attempt .

In which it works halfway

The traveling naturalist comes to a beautiful new bridge. At the well in front of the customs house, the young customs officer combs her damp hair from her morning wash. Reinhart compliments her, chats with her and hears that it was the young woman's lover who designed the bridge so slim and slim. Of course, in order to receive the contract, the young master builder had to take the hunchbacked daughter of a councilor as his wife. Since then he has only stealthily looked at her, his ex-girlfriend, and no longer dares to say hello. In return they knew and said hello to all river boatmen, and whoever crossed the bridge would turn to look at it. Reinhart's knightly offer that he too would like to spread praise for her beauty - for a kiss - she refuses. “I will still speak like that, even if you don't kiss me, wicked beauty!” Then she swings up to him, hugs him and kisses him with a laugh. But she does not blush, though there was the most comfortable and graceful place for it on her white face.

In what the other half succeeds

At lunchtime, Mr. Reinhart stays in a village parsonage. His acquaintances, the pastors, praise their family life as a finely crafted work of art of the divine world government, while the blooming daughter puts on her sky-blue silk dress for the sake of the visitor: She had also unleashed two golden curls and tied a snow-white kitchen apron; and she put a pudding on the table as carefully as if she were holding the globe. She smelled pleasantly of the spicy cake she had just baked. When saying goodbye, she secretly waves the guest behind a lilac bush and hands him a letter to her friend in the country house on the mountain. Reinhart seizes the opportunity: She stood still, trembling, and when he hugged her, she even got up on her toes and kissed him with closed eyes, doused with red over and over, but without just smiling, rather so seriously and devoutly, as if she were taking the sacrament.

How to avoid going backwards

In the “zum Waldhorn” inn, Reinhart has oats poured out for the horse and talks to the lonely, good-looking landlady's daughter. He withholds the compliments that she would like to hear, talks about the hay harvest and the prices, and teases her with them until she asks him to flirt: “Go ahead, sir! and be funny and cheeky, and I will act graceful and brittle! ”But now he is speechless because of her glib and she denies the conversation with rudeness and strange flattery almost alone. The researcher refrains from the attempted kiss, especially since he predicts that the beautiful woman will laugh but not blush. Because already it urges him to make no more useless attempts and to make himself worthy of the lovely success in advance . He politely bids farewell, excited to see what awaits him at the pastor's daughter's friend.

Mr. Reinhart begins to sense the scope of his enterprise

The traveler has taken a side path that soon gets lost in the thicket of a mountain forest. When he reached the heights after arduous wandering, the wilderness gave way to an artistic park. Horse and rider cause some damage on the winding paths and come to a standstill in the middle of flowerbeds in front of a delicate grating. In the glow of the evening sun, Reinhart sees a terrace with a country house surrounded by old trees. In front of it, at a marble fountain with a bowl carried by dolphins, stands a slender woman in a white summer dress and arranges a basket of freshly cut roses. Reinhart dismounts, opens the wallet and hands her - instead of the letter - the paper with the gallant verse: She held it between both hands and looked at the very confused and blushing Mr. Reinhart with wide eyes, while it was doubtful whether it was angry or in a good mood to twitch her lips. When the latter corrects his mistake , stammering apologies , her expression brightens. She greets the intruder with a mischievous sermon, whereupon he comes back and answers in the same tone. He secretly resolves to try old Logau's little saying here or nowhere .

In what a question is asked

Lucie , the lady is called, goes away to report the arrival of a guest to the sick host, her uncle. Herr Reinhart accepts her invitation to take a look around the house and examines the pictures and books in her study. A collection of autobiographies is close at hand by the desk, plans for parks are on another table, and vocabulary books and dictionaries on a third. What he sees fills him with respect, but it also almost makes him jealous . When Lucie returns, he exclaims: “Why are you doing all this?” To which, instead of answering, she asks him to sit at the table with a little stricter courtesy .

From a foolish virgin

Although the guest immediately sees what is wrong with his question, he behaves again wrongly at dinner, which is also attended by Lucie's pretty maids. First he mentions his eye disease and quotes an old folk medicine book: Sick eyes are to be strengthened and become healthy by diligent looking at beautiful women . Then, plagued by imprudent sincerity, he relates the complete course and nature of his excursion . Now it's enough for Lucie: she rises from the table with a flush of anger: “So you are thinking of continuing your elegant adventures in this house?” Reinhart barely manages to avert his expulsion, but has to show that he is not up to anything. deliver the nefarious rhyming slip . After Lucie has burned the paper, she lets the girls take out their spinning wheels and tells the story of a foolish maiden , the landlord's daughter who, as a precaution, did not allow the naturalist to kiss him while he was resting in the "French horn". Her name is Salome .

- Salome, a beauty as a young girl, considers herself exceptionally smart because of her nimble mouth. Without ever having learned anything right - she can only read and write with difficulty - she sets out early on to ensnare one of the young city lords, who gather in droves on hunting trips in the "French horn" and court her. To her grief, however, no one means it seriously, least of all a Junker Drogo, who stalks her the most and outperforms society when it comes to thinking up gross teasing. It occurs to him to pretend that Salome has secretly heard him. In order to make a fool of his buddies, who sneak up on him everywhere, he sits down in a dark gazebo in the evening and fakes a tête-à-tête with whispers and kisses in the air . Little does he know that Salome previously hid in the arbor in order to sulk undisturbed. In a flash she seizes the opportunity, throws herself on his neck and the air kisses become real kisses. The crowd assaults the couple with hello and congratulations, Salome's parents and a frowning brother demand an explanation, and so Drogo has no choice but to become engaged to her.

- But there is no wedding. Transplanted to the city, where she is supposed to learn finer manners from friends of her future in-laws, Salome is so clumsy that she is soon only called the camel behind her back . When one day the couple's intimate get-together ends in a yawning duet for lack of something to talk about, the groom calls them that himself. Salome's anger seizes: She throws his bride's presents at Drogo's feet, leaves the house on the spot and runs back to the village to her parents, crying loudly.

She's still sitting there, concludes Lucie. Too fine for a country man, too coarse for a city dweller, pursue her favorite mood of despising men and playing with them.

Regine

Despite all recognition of the narrator's free point of view, Reinhart finds this judgment too harsh. The punitive allusions to his kissing adventures have not escaped him either. So he decides to stand up to Lucie and defend the beautiful woman who was left behind: After all, she has shown pride. Perhaps a truly educated, intellectually superior man could find a worthwhile task in “tying the rice of such a beautiful vine to the stick and pulling it straight.” Lucie looks at him pityingly: “Noble gardener!” […] “But those So you don't reveal beauty as easily as your intellect? " Beauty is not the word, says Reinhart, but pleasure, and if the face, " the figurehead of the physical as well as the spiritual human being " pleases in the long run, it could be beyond all the differences between Stand, education and temperament hold a couple together. Lucie doesn't accept any of this , turns it mercilessly against him: Now she finally understands: “The pleasing face becomes the characteristic of the buyer who goes to the slave market and checks the ability of the goods to be refined, or isn't it?” With such “oriental views “ , She predicts, he will one day get a maid from the kitchen.

The girls giggle and prick up their ears, Reinhart takes the cue calmly: He doesn't know what is in store for him, but he has experienced the case “that a respected and very educated young man really took a maid from the herd and was happy with him for so long you lived until she really became an equal lady of the world, whereupon the disaster hit. " He says:

- The American Erwin Altenauer, embassy secretary in a German capital, sees the land of his ancestors in a romantic light and hopes to bring a very sensible and exemplary German woman home across the ocean. However, what sparkles from afar as the Rheingold of the Nibelungen song turns out in the capital's salons as Talmi , and in the civil wreath province the gossip bother him with any resulting compound is coated immediately. So for the time being he gets married out of his head. Then he meets the simply dressed Regine on the stairs to his apartment, who is on duty in the same house. The maid's stature, gait and noble facial features remind him of a king's child from old German legend.

- Regine quickly realizes that she has no intrusiveness to fear from the strange gentleman, and secretly meets with him in his room to chat. She is the youngest child of a large family of farm workers who support her with her low wages. Brothers and sisters make her grief and sometimes she thinks of emigrating to leave the misery behind. Erwin teaches her a little English and is amazed at how easily she learns. Finally he asks her if she would like to be his wife. Then she bursts into tears and flees. He follows her, finds her with her relatives and asks for her hand. After he has paid the debts on the tiny farmer's estate, Regine gets into the carriage with him. A few months later she learned to wear good clothes and she goes on her honeymoon at his side.

The girls have stopped spinning and have started dreaming. Lucie sends her to bed, fearing that the announced disaster will be related to education. Reinhart offers to spare her the end; after all, he contradicts his own tenets. But she wants to hear the whole truth.

- Carefully guided by Erwin, Regine begins to catch up on what she lacks in terms of education and lifestyle. When the couple returned to Germany from long stays in London and Paris, no one recognized the former Cinderella in the beautiful lady . An urgent family matter calls Erwin to America. Regine pleads with him to take her with him, but he travels alone because of the onset of autumn storms, but also because he only wants to introduce her to Altenauer's house after he has completed his educational work. Obsessed with the idea of transforming Regine into a picture of transfigured German folk tales, he recommends her to the care of three women who have a reputation for great and beautiful education .

- What he does not know is that behind their backs, these ladies are called " the three Fates " because they eventually cut the thread of life from whatever they took care of . In the need to shine for herself, they soon make Regine the object of a beauty cult and induce the innocent to sit as a model for an enterprising painter. So it happens that on his return Erwin encounters portraits of his wife in strange places, including a half-act . This adorns the apartment of a young diplomatic colleague. He thinks Regine has changed, and reacts strangely disturbed to his questions. When he learned from a reliable source that she had received a man's visit during his absence, her infidelity hardly seemed to him to be in any doubt. But a feeling of complicity prevents him from condemning her, in fact, he does not even confront her. He silently awaits an explanation from her. But Regine, who suspects nothing of his suspicions, is silent.

- She is also silent when leaving for America, on the week-long journey across the sea and after moving into Altenauer's house. Since Erwin is about to leave and the house residents treat the melancholy young woman with great care, she soon lives there like a voluntary prisoner . On the way Erwin feels twice the burden of misery that he and Regine get into and breaks off his journey. Determined to discuss it wholeheartedly, he returns home, rushes to her and finds her hanged in her bedchamber. Her suicide note shows that she wanted to spare him from being married to a criminal's sister. The night visitor was her brother, who slew his employer in an argument. Regine helped him to escape, but he was arrested a little later, convicted of a robbery on false appearances and executed.

Altenauer returned to Germany to take care of Regine's family, but did not remarry, Reinhart ends his story. Lucie thoughtfully admits to him that the three Fates and the painter were a bad form of education that had an impact on Regine's fate. But Erwin had neglected to "give his women's education the right backbone" out of vanity . It's gotten late, people are withdrawing. She is almost afraid, says Lucie when saying goodbye, “to see the beautiful person hanging on a silk cord like a mythical heroine in a dream” .

The poor baroness

Lucie's uncle, the retired colonel, is led to the breakfast table on crutches. He looks the guest sharply in the eye and realizes that as a young lieutenant he was close friends with his parents. The discovery sets off a cheerful conversation in which the uncle teases his niece a little: "I hope there is a beautiful old maid of her who will stay with me forever and grow pious roses on my grave" . Lucie passes on the teasing: That could easily happen if views like those of Mr. Reinhart prevail: “Just imagine, uncle, […] the educated men now only associate themselves with maids, peasant women and the like; but we educated girls have to take our house servants and coachmen in return for retaliation, and then one ponders a little! ” Whether Reinhart might have another stair marriage in store? The guest replies in the affirmative, announces "a marriage out of pure compassion" and says:

- Brandolf, a young legal scholar, son of a bourgeois landowner, is only happy when he can improve people, be it through rewards or through educational punishments. One day he overlooks a maid on the stairs to a friend's apartment and nudges her hard. When he reproaches himself for this, the friends laugh at him: the person is a baroness, too stingy to keep a maid, too proud of the nobility to have a word with the residents. Brandolf immediately decides to improve her, and since the lady lives from the subletting, he moves in with her. But his zeal has come to nothing: the Baroness Hedwig von Lohausen is shy of people, but not haughty, and what appears to be greed turns out to be an inevitable thrift. The actually pretty, but careworn and cinderella-like woman feeds on almost nothing. One winter morning Brandolf finds her helpless in her freezing bedroom with a high fever. He looks after the doctor and nurse and clears one of his rooms for her. He fears for her life for weeks; then she smiles at him for the first time, while a faint reddish sheen, like that on the roses, spreads over the pale cheeks . (The narrator cannot help but weave in the nefarious epithet at this point ).

- As Hedwig's recovery progresses, she confides her story to Brandolf: In the von Lohausen family, men have been wasting their wives' dowries for generations. She herself was betrayed of her inheritance by a villainous trick. She married her two brothers to what appeared to be a man of honor, who then brutally abused her, as did her child, who died as a result. Although she got a divorce, the three accomplices have disappeared with their fortune, only the feudal household effects remain with her. She wants to sell it now and look for a job as a housekeeper. Brandolf, delighted, points her to his widowed father. After Hedwig had managed his house for one summer, the old man wanted her to be his daughter-in-law and urged Brandolf to marry. Neither of them need persuasion, their wedding day is set for the grape harvest festival.

- Then the Lohausen brothers and their accomplice reappear. You gambled away Hedwig's fortune on the stock exchange and then sat in prison for fraudulent bills. Brandolf, worried about Hedwig, comes up with a plan to get the three of them off her neck once and for all by means of an educational punitive action. He has the Junkers, who have meanwhile sunk into begging musicians, invited to his wedding. For money and plenty of food, they are supposed to embody the devils of bad wine in the masked procession of the winegrowers and play their miserable music. On the wedding day, the three are dressed up as Krampus and dragged on their devil's tails in front of the bride's pavilion. Hedwig doesn't recognize them and waves to them in amusement; but they do recognize their abused sister and wife. The shock to see her raised to the status of a shining bride works: a few days later they can be put on an emigrant ship to America, provided with money and passports.

The ghost seers

Lucie asks the narrator whether his noble woman's savior, Brandolf, “was not chosen in the end while he thought he was voting” . When the latter is taken aback, she explains: Wasn't he really overlooked anything when telling the story, which would indicate “a modest influence, a small procedure, [...] a remnant of his own will” from Frau von Lohausen? Reinhart, outraged, defending his character: It was far from his to describe Hedwig as a person who is wrapped with played Ohmachten their lodger, but it is ! "A female figure by their helplessness only wins and enough sex for decoration" - Helplessness as an ornament of the female sex? Lucie triumphs: “Of course, yes! That's how I understand it too! [...] one more gentle woolen sheep on the market! This time it is still about the usefulness of a good housekeeper ” . The two are now on the verge of quarreling in all seriousness. Uncle recognized this and intervened: Lucie didn't need to get excited, since she wanted to stay single; But even Reinhart had to back off: “Our freedom of choice and our glory, dear friend, is not that far away, and we mustn't insist on it that much!” He himself once “became the subject of a woman's election considerations” and shamefully inferior. Does his story interest young people?

- As the wild, daring student he once was, he sought a counterbalance and joined a fellow student of sedate nature, a Kantian who energetically attacked the romantic fantasies of his friend with reasons of reason. Little by little, they would have become inseparable, if they had also fallen in love with the same girl, rich people child, the unconventional and boyish Hildeburg. He, the narrator, had been called her marshal because of his impetuous manner and his riding skills, but her friend, because of his always cool head, her chancellor.

- That Hildeburg is seriously in love with both of them was shown in 1813 when the war of liberation broke out . When the students volunteered in droves, the marshal in the cavalry, the chancellor in the infantry, she took her friends aside when they said goodbye. Carried away by the heroic, exalted mood in the country, she solemnly vows to them that she would never become a man's wife, unless one of them. But for that the other has to fall. If both fell or both returned, she would remain single.

- A year goes by and they both return promptly, the marshal between two campaigns, the chancellor after a serious wound. Despite all the joy of seeing each other again, the trio is unhappy about their bewitched love being , especially since separation and danger to life have fanned the fire violently. Now it happens that they spend a few days in a little castle that is rumored to be home to a poltergeist. In fact, it makes a thud at night. In the morning the marshal, visibly shaken, said that he had met a ghost, a gray-veiled, witch-like grinning old woman. The Chancellor rather believes that his friend will relapse into old fantasy due to the war and offers to sleep in the haunted room the following night. Hildeburg advises against it, but he insists and - is engaged to her the next morning! She was, of course, the ghost: determined to end her conflict and belong to the one who doesn't let himself be fooled, she staged the ghost. The test passed the Chancellor, who took the ghost in his arms, whereupon it dropped the wax mask and gray covers.

The colonel added that it was clear to him at the time that the election corresponded to Hildeburg's most secret wishes. Then he dryly informs his audience that Hildeburg, real name Else, has soon married the lawyer Reinhart and will therefore be the guest's mother. "Is she still alive? and how are you? ” The naturalist, suddenly confronted with his creation, blushes. Lucie doesn't make a face, but her eyes are laughing. Then he laughs bravely, answers the question in the affirmative and kindly gives the old gentleman information. Lucie only looks at him with glee and glee when the pastor's family comes to visit in the afternoon and he has to shake hands with the daughter he has kissed so briskly behind the lilac bush.

After Reinhart befriended the idea of being the son of the most arbitrary male choice of a cocky virgin , his belligerent mood returns. Late in the evening he picks up one of Lucie's old books, which is about sea voyages and conquests of the 17th century, and discovers a story in it that seems to be a great defense against the arrogance of equal women .

Don Correa

Reinhart does not know of a third stair marriage that Lucie asks him the next morning, but the case "where a distinguished and very well-known man literally picked his nameless wife off the floor and became happy with her."

- The Portuguese naval hero Salvador Correa de Sa Benavides, already governor of Rio de Janeiro at a young age, wants a wife who loves him not for his wealth, but for himself alone. He therefore goes incognito to look for a bride. In Lisbon his eye falls on a beautiful young widow, Donna Feniza Mayor de Cercal . He follows her unnoticed in the southwest of Portugal to her rock castle high above the sea. Here, where nobody knows his face, he approaches her in the mask of a shipwrecked poor nobleman and quickly wins her favor. He ignores warnings that Feniza is a witch and the murderess of her first husband and lets himself be married to her. He lives with her for a few months as if on the island of Calypso . But when the king promises him to be appointed vice admiral through secret messengers, the commander in Correa awakens again. Against Feniza's will, he takes a horse, stunned and pale with anger, the lady of the castle has to let him go. On the way to Lisbon, he imagines her surprise with amusement when he appears before her in the glory of his true identity. On the way back, he lets his fleet anchor in the bay in front of the rock castle at night, orders a wedding party to be set up and goes ashore in the old disguise to pick up the wife. Now his surprise is when he finds her at the side of a depraved lover. He barely escapes her murder attempt. After he had Feniza and accomplices hung in the blackened ruins of the tower in which she wanted to burn him, he continued his journey to Brazil, mindful of the teaching,

- that in marriage matters, even in the good sense, one should not make artificial arrangements and perform fables, but rather leave everything to its natural course.

- Ten years pass before Don Correa comes up with a new marriage plan. He is now at war with the Dutch in Angola . When he negotiates with the black Princess Annachinga , instead of a chair, he offers her only a seat cushion. The state-wise woman evades humiliation by kneeling down a young slave from her entourage and taking a seat on her back. She gives him this, her living field chair , as a present when he leaves. Don Correa tells the slave to get up and shakes hands with the swaying woman. Moved by her beauty and the sadness in her eyes, he kisses her on both cheeks and vows never to leave her.

- But it is difficult for him to keep his word. As soon as Zambo , that is the name of the slave, has been baptized in the name of Maria, he has to snatch her away from the Jesuits who want to consecrate her to heaven. He sends her across the sea to an aunt, abbess in Rio, to have her prepared for a Christian marriage. When he tries to pick her up there, it is said that the ungrateful creature has escaped. But he learns that the abbess handed her over to the Jesuits who dragged her across the Atlantic to Cadix . He embarked immediately, but found the Spanish port closed because of the plague. With a heavy heart he sets course for Lisbon after smuggling his page Luis ashore. The cunning boy discovers Zambo in a monastery and gives her a hint where her master is staying. In the meantime the admiral has applied for her extradition from the Spanish government. Weeks go by, he is under pressure to end his stay in Europe. One night, as he was wondering whether Zambo-Maria would be better off in the monastery than at the side of a warlord, the house bell rings. Luis opens it and comes back beaming, holding the African woman. This time she really ran away. Covered with dust and exhausted, she falls at her master's feet, from where he picks her up a second time. The next morning he puts his mother's wedding ring on her hand.

The curls

When Reinhart had finished, Lucie gave him ironic applause: they wanted to remember "how useful humility is" . Then she goes over to the counterattack: Speaking of people of color, she will now also contribute a reading fruit. The Colonel speaks of a duel in which he got into, Reinhart of a cannon that is aimed at him, but both encourage her to fire:

- The young Queen Marie Antoinette had the flagjunker Thibaut von Vallormes presented a gold watch in thanks for the page service at her wedding and accompanied the gift with the words that he would have to win the charms himself over time . The harmless boy Thibaut soon turns into a dangerous person and man who conquers female hearts in order to be given small pieces of jewelry which he then hangs on his watch chain. The first such trophy, a red coral heart, has yet to be stolen from its owner; the next he acquires by finer methods. Ultimately, however, all his art of conquest amounts to false vows of love. He does not notice the disaster he is causing with it and pursues his career as a gallant officer until there is no more space on his watch chain and he is bored of collecting. In the meantime he has also advanced to become a captain and is hungry for military action.

- So he joins the expeditionary forces of the Lord of Lafayette and does not do badly as a soldier in the New World. His compatriots' enthusiasm for the American struggle for freedom sweeps him along, as does their Rousseau enthusiasm for unspoilt nature and the noble savages . The French meet both on the march through a wide river valley, in which an Indian tribe has pitched its tents. While the negotiations are taking place, there is a lot of traffic between the camps, and Thibaut would not be Lord of Vallormes if he did not take a liking to young redskinned women. One of them is called Quoneschi, a water maiden , glitters around him like a dragonfly and turns his head so much that he comes up with the plan to make her his wife: How would philosophical Paris astonish him [...] with this epitome of nature and To see the originality return to the arms and step into the salons. Since the communication between Thibaut and Quoneschi is limited to signs and a few bits of English, it remains unclear whether she understands the marriage proposal. He understands her all too well for that: She demands his watch chain and curls. Thibaut is startled. But then the trophies of an outdated culture do not seem too high a price for a bride who embodies the eternally young nature. He removes the glittering hanger from his watch and gives it up. The Indian woman leaves happily and keeps calling out tomorrow! Tomorrow! .

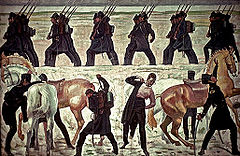

- On the next day the Indians invited the Europeans to a festival. In fact, Quoneschi does not leave Thibaut's side during the feast, so that he already reaches out his hand to caress her velvety back. But first a group of young Indians appear with war dances. (The narrator affectionately describes its leader, the wonderfully grown and wildly decorated thunder bear). Quoneschi is ecstatic at the sight of the mighty warrior, pulls Thibaut by the sleeve and shouts something. An American translates it: Donner-Bär is her bridegroom, with whom she will have a wedding today. The giant spotted his bride, dances close and - the French burst out laughing : “Parbleu! he has the charms of Herr von Vallormes hanging on his nose! ” Thibaut was just able to convince himself of the truth of this remark when the Thunder Bear Quoneschi had already swung onto his shoulders and ran away with her. The Lord of Vallormes sees neither the curls nor the girl again.

In which the epitome proves its worth

The narrator is obviously in a hurry to leave the group and smilingly apologizes to a waiting craftsman. Sadly, Reinhart sees his gentle Zambo eclipsed by Lucie's wild Quoneschi and the kiss-collecting that brought him here is compared extremely unfavorably:

- “What's the matter with your splendid niece,” he said, “just for being angry with my poor protégés for shooting satirical arrows at me? That is almost over the target! "

- “Well now,” replied the Colonel with a laugh, “she actually only defends herself against her skin, which, by the way, is a fine fur! And don't you notice that it would be less flattering for you if the Lux showed itself indifferent to the fact that you rave about all sorts of ignorant and poor creatures, one of which she has no luck or merit? "

After his penny dropped, Reinhart was also in a hurry. He saddles the rent horse who has eaten himself out on Lucie's pasture and thanks for the successful eye treatment. They split up in friendship, he promises to come back soon and goes on his way as seriously as a traveler to Africa.

Back in his laboratory, he realizes how much he misses Lucie and that he is on the way to losing his bachelor freedom. During the summer he writes her letters, but does not reveal anything about his condition, especially since he is afraid of getting a basket . Lucie sends him an invitation: Reinhart's parents are guests at the country house, and the son is urgently requested. Reinhart doesn’t allow himself to be asked twice, and when the old people set off on a visit to the pastor’s family on a beautiful day in the late summer, the youngsters are among themselves for the first time.

Your self-consciousness disappears during a conversation in the library. Reinhart asks Lucie for one of her books. With the help of the good thoughts that she wrote in the margin, he hopes to find out what captivates her about these books of life. Now she no longer owes him the answer: "I try to understand the language of people when they talk about themselves" . It is not easy; because every autobiographer, no matter how frankly he comes up with confessions, conceals any mistakes and weaknesses:

- “When I now compare them all with one another in their sincerity, which they consider crystal clear, I ask myself: is there any human life about which nothing can be concealed, that is, under all circumstances and at all times? Is there a very true person and can one exist? "

While they were exchanging their opinions on this question, Reinhart was leafing through a book and discovered a strange bookmark: two hearts embroidered from colorful silk, one rooted in the ground, the other soaring fiery towards the sky. The picture, explains Lucie, represents earthly and heavenly love. She made it during her time in the monastery. “Because I'm a Catholic!” She adds, blushing. Reinhart finds no reason to blush, since denominational differences mean little to him. She replies: “I was not born a Catholic, I became one!” When he looks up in shock, she continues: “You see, we have a story about which you don't know whether to confess or keep it quiet ! "

- Lucie's youth story

- Her father was a Lutheran, but tolerant and open to the world. Her mother, a Catholic, joined her husband's church without a formal conversion . She herself was raised Protestant, but the father watched benevolently when the wife and child boarded the house's own boat at the cheerful Catholic church festivals to go on a pilgrimage to a nunnery downstream and spend the day with Sister Klara, the childhood friend and closest confidante of the mother , to spend.

- At the same time, a young relative of her mother's, also a Catholic, went to Lucie's parental home. Whenever he sees the child, he takes it on his lap, kisses it and calls it his little wife. Later, Lucie no longer accepts kissing, but becomes dissatisfied if the visitor forgets to call her his little wife or bride. Leodegar , as he is called, now comes less often. The child is all the more impressed with his increasingly brilliant appearance as a student, as a military man, as a cosmopolitan.

- At twelve, Lucie loses her mother. The father goes on a journey and leaves the daughter in the care of a housekeeper and a governess. Both are preoccupied with their own business and have no understanding of the needs of the young orphan. Lucie withdraws to the world of books alone. When she reads Schiller's Wallenstein , she falls in love with the figure of Max Piccolomini and fantasizes about the role of Thekla , who is mourning his grave. She notices that the dead hero is increasingly taking on the features of the distant Leodegar.

- When he returned home again, Lucie, not yet quite sixteen, received him in place of the father who had been away. Your ambition as a hostess has awakened. She spares no effort in giving him a festive farewell and gives herself a grown-up reputation with clothing and jewelry. But at the table she sits stiffly and silently like a wooden doll , while the governess takes the guest for herself. Even when taking a walk, the teacher steps ahead on Leodegar's arm, the pupil behind them, deadly unhappy, secretly shedding tears. Leodegar notices it, and when the governess pursues her lucrative private pleasure, the hunt for rare beetles, for a while, he pulls Lucie onto a bench and asks: "A bride, a little woman who is crying, where is this going?"

- Then I burst into tears again; I longed for trust, for friendship and love, for a better home than I owned, and this longing now, without my being able to change it, vented with the strange words:

- “Cousin Leodegar! When are you going to marry me? "

- The not so young man thinks about it and smiles strangely. Then he says: “You good girl, once you’re Catholic, the wedding will be!” When he’s about to be tender, the governess returns.

- The following night, Lucie secretly packs her things, leaves a message where she can be found, and gets on the boat. She arrives at the monastery for early mass, turns to Sister Klara and tells her that she wants to become a Catholic. Klara shakes her head, but reports the matter dutifully. After the application has been thoroughly examined, the monastery is instructed to prepare the daughter of a Catholic for the return to the bosom of the church, but to keep the conversion secret until the person to be baptized into religion . After the baptism, Lucie's Protestant conscience reports. She confesses the reason for her step to Klara, whereupon she sheds tears in thoughts of her own youthful suffering, but she bids to be silent and busy with the creation of the symbolic picture as a distraction and warning.

- When Lucie's father returns home, he is furious and dismisses both supervisors. Then he brings the runaway back from the monastery. Have you tried to get them to convert? According to the truth and yet ambiguous , Lucie denies. In order to counteract a possible infection from the Catholic atmosphere, her father is now taking her to a boarding school run by Protestants. Here, with discreet teachers and well-behaved classmates, Lucie finds her cheerfulness again, but has to be careful at every turn not to reveal her secret.

- The only one who could release her from the unworthy game of hide-and-seek, Leodegar, still shines in her soul, but as distant and dumb as a star. After waiting in vain for two years, she learns that he has joined the Redemptorist Order and has become a famous penitential preacher. He will certainly take it to the cardinal, her father writes to her from Rome, where he ran into Leodegar and noticed his fanatical gaze. It is the last letter from his father, shortly afterwards he develops a fever through careless travel and dies.

The narrator ends, her uncle has become guardian until the age of majority. Together with him, who has no idea of her conversion, she bought the country house seven years ago and has lived here ever since:

- I soon recovered from the premature foolish passion and its subject, as it fell like scales from my eyes. But through my pranks, I had my youth, life and happiness, or whatever you think, shut off from my face. I couldn't undo the move if I didn't want to get into the rumor as an adventurous double convert. In the meantime I have learned to console myself with the idea that my story has saved me from later disaster, evil and devilries, which I could have experienced or caused without this experience. There are also diseases that are inoculated into children so that they are protected from them later!

Reinhart does not want to accept the parable of the vaccination. What happened to her happened only to beings "whose noble, innocent generosity of the heart hurries ahead of the time impatiently, innocently and unconsciously." To this generosity belongs the child's belief in the joke of the cardinal like one dove's wing to another, "and with such wings they fly Angels among men ” . Lucie thanks, as usual, mischievously for the politeness and the “gracious judgment” , but breathes audibly: “You see, now I am completely freed from the cursed secrecy. How difficult it is to find the kind of confessor you need! "

Now both are forced to go outside. On a walk through the forest down to the village and the river, you will encounter all sorts of small natural and cultural wonders: an oak tree holding a beech tree in his arms, a snake that the knowledgeable Reinhart frees from a brook crab that tries to eat it, and finally a shoemaker who sings Goethe's youth song "With a painted gang" while pulling pitch wire in his workshop, saxoning and accompanied by loud canaries. They are actually supposed to deliver a message to the young master from his bride, Lucie's maid. But overwhelmed by the noisy hope for life in the shoemaker's house, they forget it and turn to each other. When she kissed, Lucie's eyes were full of water, but she laughed at it and turned purple from a long-deprived and spurned feeling. Only on the way home do they remember that they have now carried out old Logau's recipe, without even thinking about it. Reinhart asks Lucie for her hand and the two return as fiancés.

Interpretations

Contemporary reviewers and readers praised the end of the epigram without going into the final punch, the verification of the epigram. When the need arose 30 years later to gain a deeper meaning from the work and to develop a central theme that unites the stories, the interpreters promised themselves the key from this epigram.

On the subject of "blushing laughter"

Blushing and laughing , physical signs of mental and spiritual processes that are completely or largely beyond the control of the will - what do they indicate? What significance does Keller attribute to them when he takes up the 200-year-old epilogue by Friedrich von Logau and processes it in terms of motifs? The cycle offers a kind of phenomenology of involuntary emotional expression: main and internal narrators distinguish between happy, sullen, triumphant, forced laughter, shameful, confused, angry, joyful blushing. Men, too, are in the epigram blush, vornweg Mr. Reinhart; he and Lucie blush the same number of times, twice even at the same time; the main phenomenon, the Galatheen-like blushing-and-laughing, announces itself several times; however, it appears in full clarity only once and at the very end. What does it mean?

Until the mid-1960s, Emil Ermatinger's interpretation was almost unreservedly true : “Blushing is the sign of shame, the feeling of the necessary moral limit; Laughter is the sign of sensual well-being, of serene freedom. "And:" Preservation of the moral barrier in the midst of free enjoyment, that was the interpretation that Keller had to give Logau's word 'blushing laugh' based on his worldview ". Mr. Reinhart, it was clear to Ermatinger, “wants to establish a good marriage by kissing, not just amusing himself.” If this is the case, the researcher does not go on a lively and spontaneous erotic journey of discovery, but pedantically and carefully looking for a bride ; he does not kiss because he feels like it, and to get to face the alluring phenomenon, but instead carries out a series of systematic personality tests in the expectation that the simultaneous blushing effect will qualify the test person as a wife. According to this, Keller would have reinterpreted the gallant epigram "out of his worldview" as a philistine adviser on the matter of choosing a wife.

In 1963 , Wolfgang Preisendanz objected to this interpretation in a widely acclaimed article. He referred to the final chapter, in which the epigram proves its worth at the moment when the two of them don't even think about the terrible recipe (Lucie), the delicious experiment (Reinhart). The attempt succeeds although or precisely because it no longer has to prove anything. Preisendanz thus opposed the view that Keller's epitome came "from the world of the bourgeois family novel " and remained caught up in it, a prejudice that the reader must come to if he followed Ermatinger's interpretation without knowing the text.

In addition, the scheme of sensuality-morality leads to an “oppressive formulaic understanding of the individual stories”. It is important to read these impartially and to check for similarities. Recapitulating came Preisendanz to the conclusion that it all epigram go to the distinction between "reality and appearance, essence and appearance, reason and surface, face and mask, shape and disguise" -Novellen to the "problematic tension between what one People represent, pretend, represent, and what he withholds, conceals, hides ”- think of Lucie's skeptical view of the sincerity of the autobiographers. It is true that in the spontaneous expression of emotions, in the Logausch phenomenon, the firm connection between the moral and physical world on which the natural scientist Reinhart trusts is revealed. But in the border area of the two worlds, where the winding paths of human arbitrariness and the straight lines of natural causality cross each other, the experimental method has lost the game. What the epigram promises can only be experienced by those who go to Lucie's territory and learn to understand human destinies with her, history and stories, foreign and personal. Here, in the labyrinth of imaginations, ambiguities, disguises, her method of doubting the shell and asking about the core is the more appropriate.

To justify this method, namely the traditional one used by the storytellers and poets, over against the modern, scientific one, that is the main concern of the author. Preisendanz's essay closes with a reference to Zola's manifesto Le roman expérimental , with which naturalism began to break out around 1880 . In this sense, the cycle is also gaining the reputation of a literary positioning: Keller addressed the epigram against the demanded by the naturalist scientific nature of literature and calls for the imperial immediacy of poetry , which he means the right at any time, even in the age of tailcoats and the railways, to tie in with the parable and the fabulous .

On the subject of the relationship between the sexes

When in 1880, shortly before the epiphany was published , Ibsen's Nora or Ein Puppenheim caused a sensation on German stages, the young theater critic Otto Brahm compared the play with the epiphany . His impression: “This poem also revolves [...] basically around the same social question, here too the author polemicizes the man's egoism, who in his wife is not an equal comrade, but rather a child to be monitored and raised, a fragile one Toys from the 'doll's house' sees “. Fritz Mauthner said in a similar way : The epiphany in his outlook on the marriage question is "as modern as George Eliot , as only Ibsen in his' Nora" and the most self-confident woman could be satisfied with the position that Keller assigns him. "Such views remained isolated. Ermatinger's reading proved to be formative. This was based on Reinhart's caricature of the three educated women and the painter in Regine and showed that Keller hates the emancipated "in the worst possible way because they seek to falsify nature by falsifying the gender differences." Under these conditions, Lucie was either not perceived as emancipated , or as a person who “has to unlearn the arrogance of the emancipated and give space to their feelings”. This image of Lucie also predominates in the feminist interpretations that have emerged since the 1980s, albeit with the difference that she is now seen as a woman who surrenders to the man in the final chapter. The semantic coloring that Ermatinger Reinhart's activities had given by the word "Brautschau" was retained regardless of its inconsistency. It found its way into literary stories, but also into extensive interpretations such as that of Gerhard Kaisers . For him, Mr. Reinhart “set out to select a lady for marital purposes in a systematic and experimental manner”.

What Lucie has for Reinhart and he for her

- “You are only loved where you are allowed to show yourself weak without provoking strength.” Theodor W. Adorno

Preisendanz's reading revealed that the cycle is not about a one-sided rehearsal, but rather a mutual examination. Behind the “banter” about marriage on the stairs and electoral glory is the question: “Who am I actually dealing with?” Lucie calls the views Reinhart brings up in the dispute against her “oriental” and compares his attitude to that of a pasha on the Slave market. The mocking defense, however, does not prevent her from attentively following the fates he tells. His three stories contain messages that concern them closely: the man should not leave the woman alone in a difficult social situation like Erwin Regine, should plant the stunted in good soil like Brandolf the poor baroness, he should offer the depressed the hand to stand up like Don Correa the Zambo. Lucie has no illusions about the precariousness of her own situation: every attentive observer has to ask himself why she, a radiant figure, spent her best years in this noble solitude in a monastery-like house - what happened there, what gnaws at her? An ordinary educated person, whether he is a reckless hooker or a serious suitor, would keep such questions quietly to himself and show his admiration for literary, independently thinking women. Reinhart, on the other hand, asks loudly and improperly: "Why are you doing all this?" He embarrasses Lucie, she blushes; But he too, since he thinks of it boiling hot, where this question boils down to: Nicest, don't you know anything better to do? or even more clearly: what did you experience? But then he tells in three attempts how a maid who grew up in misery, a divorced woman severely injured by her brothers and sisters, and finally a slave can become a long-term companion to an educated man, provided that he does not forget simple humanity through his education. Lucie notices that the strange guest doesn’t speak to her. Even the scorn with which she holds up to him the sheer self-interest that usually drives the lords of creation when they act as saviors and formers of the female race, does not deter him from defending his point of view. She likes it; if she wants to fall in love again, then not with a fickle one .

By telling strangers about love affairs, the two have explored each other, their external likes and dislikes, but also their core character. Lucie has not escaped the fact that in the Mietsgaulreiter as in Don Quixote a noble, timeless knightly heart beats. The final guarantee for this is his reaction to the disclosure of her secret. But the fact that she confides it to him shows how little she fears that he will take advantage of her social list to turn her into "a depressed housewife, such a modest, warmed-up sauerkräutchen" . Preisendanz: "Only in front of a man whose core she is completely safe can Lucie free herself from cursed secrecy ".

Conversely, Reinhart can rely on Lucie's education going in-depth, education of the heart, not glamor , a means of satisfying the urge for self-recognition and the need for power as with the three Parzen that he shows in Regine . Immediately after the nightly discussion of Regine's fate, he was sure of his affection:

- With strangely excited feelings, Reinhart went to bed in the strange house, under a roof with the most graceful woman in the world. Just as there are people whose physical body, if you accidentally touch or bump it, feels solid and sympathetic through their clothing, so there are still others whose spirit is familiar to you through the enveloping of the voice at first hearing and speaks to us fraternally , and where both meet, a good friendship is not far out of the way.

What takes the naturalist for Lucie is her spirit. The fact that this also expresses itself as a spirit of contradiction makes him temporarily faint-hearted: "I praise myself for the calm choice of a quiet, gentle, dependent female who does not rob us of our minds!" He says to himself after the story of Hildeburg's choice of spouse to continue: “But of course, these are mostly those who blush when they kiss, but don't laugh! It always takes a little mind to laugh; the animal doesn't laugh! ” Friendship , spiritual community, a relationship in which no part patronizes and dominates the other appears in the epiphany as a preliminary stage of love and a good omen of marriage.

Reinhart a male chauvinist?

The fact that Keller represents friendship as the basis of lasting love is partly recognized and partly disputed in more recent interpretations. The latter from Adolf Muschg , when he says: “Great poetry often speaks of women no differently than the beer table.” Keller's epic poem is “in an unfriendly light, examining a selection program of women's goods [...] artistic and instructive market tip [...] a higher kind of meat inspection. ”On the other hand, Gunhild Kübler finds “ a considerable emancipatory, even feminist potential ” in the epithet . Instead of the dream in which the woman by man's grace exists, “new, enlightening-egalitarian ideas of eroticism and conjugal love, as they are unique in the literature of the time.” Her conclusion: “Great poetry [...] doesn't talk about women like the beer table, and that is exactly one of the characteristics of their size. "

While most of the interpreters see a learning and development process in Reinhart, for Ursula Amrein and the majority of feminist interpreters he remains a chauvinist , “who, in order to assure himself of his male superiority, demonstrates in two cases how the inferiority of women becomes unconditional One of the prerequisites for a happy marriage. "Lucie's self-revelation appears as an act of submission, Reinhart's reaction to it as an" integrative appropriation of the woman ":" This appropriation takes place when the man subordinates the woman as a confessor to his law and she thus as his creature in the order represented by it transferred. As a confessor, he also solves the woman's riddle. This process, which is presented in the text as the redemption of women, actually includes their submission. Because when the man solves the woman's secret, he gains power over her. ” Gerhard Kaiser sees it similarly when he predicts a doll's house fate for Lucie: it is true that she“ will not shrink to a home at the stove ”; Nevertheless: "The narrowed natural scientist will be a happy natural scientist in the future, to whom the cultivated, loving wife caresses the wrinkles of the forehead and the tiredness of the eyes." Read this way, Keller's epitome does not amount to the recognition of Lucie's intellectual equality and equality, but to Appropriation, utilization and taming of an unruly .

On the subject of "two cultures"

According to Kaiser, Reinhart and Lucie represent different ways of life, the scientific-technical and the aesthetic-literary - two cultures in the sense of Charles Percy Snow's thesis , which have become increasingly foreign to each other since the 19th century. Their opposition is fundamentally effective in the dispute about the equality of men and women and is not canceled by the peace kiss of the opponents. Especially here, during a walk in the forest, a remark by Reinhart clearly shows the break line between his scientific explanation of the world and Lucie's way of life based on language and understanding. The dispute over primacy between the two cultures continues behind the back of the united couple. The story does not end with a triumph of Lucie's culture, the author deliberately keeps the outcome in suspension, but clearly indicates which side he is leaning towards. This is done through interwoven references to Goethe and his criticism of Newtonian optics . In addition, Lucie is pronounced as the superior and "humanly richer figure".

Reinhart an "enlightened dark man"?

The epitaph as a justification of the poetic in the face of the scientific challenge - Kaiser agrees with Preisendanz's thesis, but does not share his view that the natural scientist also contributes to this Keller project, unless as a negative contrast figure. Reinhart appears to Kaiser as “an enlightened dark man” who for a time comes closer to Lucie's spiritual world, but who never fully emerges from his darkened study. Even in the love scene, he behaved strangely wooden and callous. Unlike Lucie, who entrusts him with her eventful youth story, he has no past worth telling, is historically devoid of history and therefore appears faceless - a life-planning rationalist, as his combination of (useful) eye care with (pleasant) bride-to-be shows. With him, the “narrow-eyed scientist”, “a leading type of the time is turned into a questionable hero”, a person whose “abstract scientific approach to life and the world has something killing about it”. Kaiser is astonished that such a person, as a charming conversationalist and serious narrator, can “speak” and win over a woman like Lucie. To explain it, he refers to the Keller's imperial immediacy of poetry : The main plot is like in a fairy tale, where “Dummies […] win happiness in the end” and wise women have wondrous cathartic powers.

Kaiser's view has recently been contested from the biographical side. Letters from Keller's friend Jakob Christian Heusser , which were only published in 2011, show that the Reinhart figure is not fictitious. Keller equipped them with trains from Heusser, a scientist. The two met in Berlin in 1851, where Heusser was working on crystal-optical examinations in Heinrich Gustav Magnus' laboratory . Many details of the first chapter, the description of the work chamber, the apparatus built in it, even Reinhart's eye pain, owe to the author's dealings with this friend. The fiction begins at the point where Keller lets the naturalist discover the Logausche epic poem, which in reality he himself discovered in 1851. In this respect, the Reinhart figure is a mixed portrait in which Heusser's features merged with Keller's features. This - so the argument goes - explains the author's attitude towards his character: friendly irony mixed with self-irony. If Keller had wanted the natural scientist to appear as a sinister pedant or in some other way dark man, he would have had the means of biting satire at his disposal. Instead, he rewarded him with a woman like Lucie. The demonization of the Reinhart figure, noticeable in secondary literature since the 1960s, is an interpretive artifact and expression of the resentment against natural scientists widespread in the humanities ; thus itself a symptom of the increasing alienation between the "two cultures".

"Keller Lessing"

Klaus Jeziorkowski examines the references to other literary texts woven into the epiphany . He draws attention to a scene in the opening chapter from which another, less gloomy and contradicting picture of the naturalist Reinhart emerges: When Reinhart reflects on the long neglected human things, his collection of aesthetic literature occurs to him. It stands in a floor chamber. After he has let the daylight in again, he climbs up there and first of all picks up a volume of Lessing - the volume in which he discovers the Logausche epigram a little later. He pulls it out, frees it from the dust and says:

- “Come on, brave Lessing! It is true that every laundress leads you in the mouth, but without having a clue of your real being, which is nothing other than eternal youth and skill for all things, the unconditional good will without falsehood and gilded in fire. "

Jeziorkowski: "For Keller, Lessing is the light-bringer, the enlightener in person". There is, therefore, not a little of Keller's character in the figure of the natural scientist, also in his extravagant remark about people who only talk about the poet. Jeziorkowski identifies the laundresses as writers who aroused Keller's anger with bad literary stories and adulation of Lessing.

Obviously, the natural scientist dealt intensively and critically with aesthetic literature before devoting himself entirely to studying nature. Without such a prehistory, the main plot would not get going, or would end at the latest when Lucie invites her guest to take a look around the country house. A specialist with limited horizons would hardly be interested in Lucie's book collection, feel no jealousy of her goings-on and ask no provocative questions; he couldn't compete with her.

Educational history of a natural scientist

Reinhart only mentions his somewhat arbitrary and unregulated studies to Lucie once . More about the naturalist's way of life, philosophy and educational history can be found in the opening chapter. Preisendanz examined the wealth of allusions and the telling irony of this “epic entrance” for the first time: the mention of a work by Darwin in the very first sentence ( law of natural selection ), the description of Reinhart's work chamber and inventory ( study of a Doctor Fausten , but definitely into the modern age , Translated comfortably and gracefully ), the remark about the aesthetic writings in the attic room ( a neglected amount of books ) and other more. The following passage, read against the background of the Lessing invocation , shows why Reinharts lives with his back to the literary business of his present:

- Moral things, he used to say, flutter in the air like a discolored and decrepit butterfly anyway; but the thread by which they flutter is well tied, and they will not slip away from us, even if they always show the greatest desire to make themselves invisible.

- But now, as I said, he felt uncomfortable [...].

The reason for turning away is the discolored, shabby education, the museum's admiration for classics, the cult around the plastered Venus, which he caricatures in Regine . Goethe's Faust , "smarter than all the monkeys / doctors, masters, clerks and priests", turned to magic. Kellers Reinhart, disgruntled by the litter of writers, concentrated on exploring the material and sensual . This happened in the trust in the firm connection between the natural laws and the moral phenomena. But now he feels that this trust cannot prove itself if you lock yourself up and postpone the encounter with life on the back burner.

With this insight, the modern Faust leaves his laboratory, drives out - the gallant poem serves as Mephistopheles ' magical cloak - and meets Lucie. It is she who brings life back to life again to those who are tired of education. Through them, the author addresses his readership and encourages the representatives of the long-established literary culture to approach the representatives of the newly emerging culture and their literary entourage with self-confidence.

From fluoroscopy to enlightenment

The opening chapter of the epitome is peppered with ironic points against natural science. The first sentence already contains one:

- About twenty-five years ago, when the natural sciences were again at their highest peak, although the law of natural selection was not yet known, one day Mr. Reinhart opened his shutters [...].

Initially, the plot is dated to the mid-1850s, the time of the materialism dispute . The point is directed against the glory of the scientific spokesmen in this dispute, who see the summit of the explanation of the world reached with each new discovery, where a little later an even more recent one surpasses it. The author-narrator continues in the same tone and describes the study of the modern Faust: No stuffed monster hung on a smoky vault, but a living frog humbly crouched in a glass and waited for its hour . He may wait a while, because the researcher is currently investigating the structure of crystals and instead of frogs he is stretching rays of light over the ordeal - an allusion to Goethe's polemic against Newton . In this environment, Mr. Reinhart enjoys the great spectacle [...] which seems to lead the infinite richness of the phenomena inexorably back to a simplest unity, where it is said that in the beginning there was power or something - again an allusion to Faust, combined with a swipe at Ludwig Büchner's strength and substance and scientific reductionism .

The names of the main characters already show that such peaks are firmly anchored in the structure of the frame narrative: The crystal researcher, whose name is made up of the words “pure” and “hard”, becomes the object of investigation himself. He gets to do with a female being who is called “Lux, my light” . This light being stimulates him to a kind of phosphorescence in the form of that imprudent sincerity that attacks him at the table. It is penetrated by the hard rays of their satirical arrows , heating up considerably, but retaining its consistency . In the end he is enlightened , now shines himself and calls the time when he did not yet know Lucie, ante lucem, before daybreak . The text analysis of the natural scientist Henrike Hildebrandt leads on the trail of this Concetto . Interpreters of the humanities - the vast majority in number - recognize less the object in the crystal body than the tool of investigation, the light-splitting prism . While Keller lets Reinhart do something completely new, crystallography , a research direction with a future, they see him repeating those ancient experiments whose interpretation by Newton once prompted Goethe's polemics. At the end of this trail he is discovered as a Newtonian converted to Goetheanism . There is no reference in the text to such a reversal. Reinhart follows Goethe's call to "Friends flee the dark chamber", but this does not turn the declared despiser of cults into a follower of the theory of colors , the signature of the Goethe cult. In short: Keller's ironic defense against the arrogance of his equal natural science does not cross the line, does not revert to the arrogance of the poet, who demands unrestricted interpretative sovereignty for himself and his followers in the field of human and moral issues. At the end of the epiphany , Reinhart remains what he was at the beginning, researcher, more seeker of truth than owner of truth, committed to empiricism . This emerges from a remark he makes in the final chapter.

Darwin in epiphany

What does the mention of the law of natural selection at the “epic entrance” of the epiphany mean? "Why are we reminded of Darwin of all people, perhaps the most momentous scientific work of the 19th century, although it was not yet known at the time of the incident?"

As the Lessing passage shows, Reinhart is a bearer of hope for the author, a natural scientist as he should be: someone who sticks to the facts, even if - as in the Regine story - they run counter to his beautiful theory; not an ideological propagandist, free of expert airs, but when it comes down to it, knowledgeable about nature and present with advice and action. For example, on the walk in the woods, when he gives Lucie to hold the snake that had been attacked by a cancer ("Just hold on tight with both hands, it's not a poisonous snake!") . Lucie overcomes her shyness, the little rescue adventure makes her happy ("how glad I am that I learned to hold the creature in my hands!") .

- “Yes,” replied Reinhart, “we are delighted to be able to protect the individual for the moment in the general war of extermination, as far as our power and mood extend, while we greedily eat.” [...]

Jürgen Rothenberg, who reads Keller's epitome as an anti-Darwinist polemic , quotes the comment, but leaves it out while we are greedily eating . Kaiser complains about this and argues against it that "Reinhart's last word on the snake adventure is Darwinian." The remark exactly marks the fault line between the two cultures. Through them the natural scientist again reveals his lack of life. He appeared as a lecturer, as a distanced theorist, as a statuary authority and suddenly presented a comprehensive interpretation of nature; it lacks “the slightest undertone of an emotional perception of what is happening. Rather, the situation is X-rayed like a flash, its living surface, its breathing skin, so to speak, penetrated and skeletonized into a deadly world of predators ”. This contradicts what Reinhart says further as he watches as the freed snake slips along the path through the grass:

- [...] "But you see, this time the creature seems to be grateful and to escort us!"

Reinhart knows that Lucie can take the truth. But now it seems to him as if he had put too much of it on her by thinking out loud. Concerned, he directs her mind back to the friendly, fairytale-like nature of the scene. In this context, the remark about the general war of extermination in nature takes on a different meaning. Her gesture is also not the one that Kaiser implies: Reinhart does not trump, does not use ideological propaganda speech, least of all he speaks as a cynic . It expresses what an attentive observer, who looks at the relationship between man and nature without illusion, goes through the head of such a rescue adventure. His remark also testifies to feeling, namely to that quiet basic mourning without which, according to Keller, there is no real joy. As far as the fault line between the two cultures and the shadowy presence of the new doctrine of descent are concerned, his words also say this: We do well not to forget our animal nature, especially in the exhilaration of happiness above our human grandeur. Darwin expresses himself in the closing words of his second major work, The Descent of Man and Sexual Selection , whose key messages were known to Keller, in roughly the same sense:

- I have given the evidence to the best of my ability, and we must acknowledge, as it seems to me, that man, with all his noble qualities, with the sympathy he feels for the lowest, with the benevolence which he does not merely show towards other people, but also extends to the lowest living beings, with his god-like intellect, which has penetrated the movements and constitution of the solar system, but with all these high forces still bears in his body the indelible stamp of his lower origin.

On the subject of literary poetry

Reinhart's invocation of Lessing, the discovery of the Logausch epigram, the allusions to Goethe's Faust ; the examination of Lucie's books of life with mention of a good two dozen work titles on and off the main street from the younger Pliny to Darwin - all of this makes the epitome a learned poem , a literary poem . There are also mythological and biblical allusions, references to characters from fairy tales and legends, as well as the formal traditions that the work continues, Boccaccio's Decamerone and Cervantes' Don Quixote . These - in the broadest sense - figures are not adornment of knowledge, educational ballast, the narrator uses them economically, lets them intervene in the plot, even if not all as dramatically as the Logau epigram at the beginning and the little Goethe song at the end. “If you wanted to ignore the reflexes of cultural and literary history in the epithet , you would not separate an ingredient, but would ruin the work.” Says Klaus Jeziorkowski , who follows some of these references down to their ramifications and further, less obvious ones discovered, for example in Regine Keller's defensive stance against Richard Wagner's Nibelungen poetry. Like Altenauer's “early Wagnerian” glorified image of Germany, Don Correa's astrological fables, Reinhart's thoughtless handling of the epigram and Lucie's young-girl identification with Schiller's Thekla show that the characters in the epiphany “are generally endangered by the fact that they are between them and reality Literature assumes that they act, think, live in literary form, barricade their access to reality through books. You have a book in front of your head ”. Reinhart expresses a related thought after the Colonel shed a light on the reason for Lucie's resistance: “That's how it works,” he said with an imperceptible movement, “if one always speaks in pictures and parables, then one finally understands reality no longer and becomes rude. " Jeziorkowski:

- This poetry tells of the wrong "getting a picture" through literature and reading, of dangerous idealization and of correcting what is wrong. To get an idea of literature, of systems - which are essentially idealistic systems - means missing the world and life; letting go of such constructions leads into the world and life - this never explicitly given “morality” makes the epic poem a model for overcoming classical historicism of the 19th century, a playful victory over it. In a dialectical way, the abolition of the secular historicism compulsion is only possible if Das Sinngedicht presents itself as a literary poem of the purest water, as a fully developed product of historicism.

On the subject of mythology

Nereids, mermaids, nymphs