The three just comb-makers

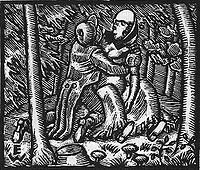

The three just comb makers (so in the first print and in the text-critical editions, Kammacher often in later prints) is a novella by the Swiss poet Gottfried Keller . Written in Berlin in 1855 and published for the first time in the Die People von Seldwyla collection in 1856 , it is now one of Keller's better-known stories and is an example of a realistic grotesque . The story is about three German journeymen who work for a Seldwyler master craftsman , all three hardworking, economical, frugal, calculating and conflict-averse. In spite of this - or precisely because of this - they become bitter rivals : everyone wants to buy combing, and everyone wants to marry the same wealthy maid to do so. A decisive race ensues, which ends badly for two of the journeymen. But the winner also ends ingloriously as a henpecked hero .

content

Jobst, the Saxon, does no harm to anyone and has endured it for years with low fare and monotonous work in combing, always with the goal of becoming a master himself here. So he avoids all of the Seldwyler's costly amusements and hides fearfully in the workshop from their political turmoil. He's already saved a pretty penny, and his bill seems to be paying off. Two new journeymen arrive one after the other, the Bavarian Fridolin and the Swabian Dietrich. At first Jobst hopes to sit them out, but then he has to find out that both are cut from the same cloth as he and are also pursuing the same goal. For fear of being released prematurely, the three toil as if obsessively, filling their master's pockets and avoiding any friction with one another; they even sleep in the same bed without quarreling about the most comfortable place, so that the comforter lay on them like a piece of paper on three pegs . But Jobst secretly spies out the other's hiding places: Fridolin's treasure is almost the same as his own, which fills him with concern and admiration. On the other hand, Dietrich, as the youngest and most recently arrived, has hardly put back a bit.

But Dietrich finds out that the maid Züs Bünzlin, who does the laundry for the three of them, has a validity letter whose value outweighs the savings of his competitors. Züs goes well with the journeyman with her imagined cleverness. She also knows how to bring out her feminine charms. So the little swagger begins to court the maid, and speaks to her as hard as he can; and she could endure a good deal of praise; yes, she loved its pepper the more the stronger it was . However, the two older journeymen find out about Dietrich and try to imitate him, often messing around with awkward compliments. This is just right for Züs, as she can develop the full splendor of her education. In addition, she keeps the journeymen in check with speeches about renunciation and altruism. The more lofty the nonsense she utters, the more humble they hang on her lips.

In the meantime, the owner of the combing shop has earned a lot of money from the journeymen: he buckled his belt a few more holes and played a major role in the city, while the foolish workers in the dark workshop toiled day and night and wanted to work each other out . Since, as Seldwyler, he naturally lives beyond his means, the gold mine soon has twice as much debt as it throws off. The overproduction of combs is finally causing a decline in business. The master is forced to dismiss two journeymen. A world collapses for the three righteous, everyone kneels down to ask to be allowed to stay. But the master very well guesses their intentions, resents them and decides to make a fool of his potential business successors by letting them run each other. He acts as if the choice is difficult for him and fires all three. The following Sunday morning they have to pack their things and walk half an hour out of town. Whoever is the first to seek employment with him again, he will keep; the others can see where they are. Desperate, the journeymen run to Züs and beg her to choose one of them. But the maiden orders them to regard the race as a test imposed by heaven and first wants to extend her hand to the winner.

On Sunday morning she accompanies the ready-to-walk trio up a hill outside the city gate and prepares them for the absurd test with small refreshments - dried pears and plums - and an anointing sermon: “So go there and turn the folly of the wicked into wisdom the righteous! Making it the mischief out sunbathing that turns into an edifying work of testing and self-control, in an ingenious final act of a long-standing good behavior and Wettlaufes in virtue " . But she secretly wants Dietrich to lose the race; because because of his small savings he is out of the question for her as a husband. When the other two start running, she pretends to be in love and in need of help and clings to him. Dietrich, who probably notices what is being played, changes his disposition, resolves to try his luck up here and lets the wrong friend lure him onto a shady forest path. Züs, however, as a being whose thoughts are in the end as short as his senses , succumbs to his fiery words and caresses: Her heart crawled as fearful and defenseless as a beetle lying on its back, and Dietrich defeated it in everyone Way .

Meanwhile, the race between Jobst and Fridolin turns into a wild brawl. Cheered on by the Seldwyler men and women, for whom the gruesome spectacle comes in handy as Sunday afternoon entertainment, the two of them forget their destination and, surrounded by howling people, wallow in the dust of the city gate, past the comb factory and back out again. The master waits in vain for the winner, until an hour later Dietrich and Züs come in and make him a suggestion: Züs buys his house and business, her groom Dietrich rents a room from her and runs the workshop. The master accepts with pleasure, because in this way he can quickly get cash behind the backs of his creditors.

Jobst and Fridolin lay, half-dead from shame, languor and anger, in the inn where they had been taken after they had finally fallen over in the open, doggedly at each other . The next day the Saxon leaves the city and hangs himself on a tree not far from where Züs said goodbye to the three. When the Bavarian passes there a little later and sees the body, he is seized with horror. He runs away like mad, loses all hold in life and ends up as a neglected person. Dietrich the Swabian alone remained a righteous man and stayed up in the town; but he did not enjoy it much; because Züs did not give him fame at all, ruled and suppressed it and considered himself the sole source of all good.

About the work

Concept of justice

- The people of Seldwyla have shown that a whole city of unrighteous or reckless can survive in the change of times and traffic; the three comb-makers, however, that three righteous people cannot live long under one roof without getting into each other's hair .

After this frequently quoted introduction, the narrator explains what he means by "just":

- What is meant here is not heavenly righteousness or the natural righteousness of human conscience, but that bloodless righteousness which has struck out of the Lord's Prayer: And forgive us our debts, just as we forgive our debtors! because she does not incur any debts and has none outstanding; which nobody lives to suffer, but also to please nobody, work and earn well, but does not want to spend anything and finds only use in loyalty to work, but no joy. Such righteous people do not throw in lanterns, but neither do they light nor emit any light; They do all sorts of things, and one is as good to them as the other, if only it is not associated with any dangerousness ; they prefer to settle where there are quite a number of unjust in their interests; for if there were no such things between them, they would soon rub off like millstones with no grain between them. When this concerns a misfortune, they are most astonished and wail, as if they were on the spit, since they did not harm anyone; for they regard the world as a large, well-secured police station, where no one has to fear a contravention penalty if he diligently sweeps his door, does not place any flowerpots in front of the window and does not pour water out of it .

Emergence

In 1851, Keller wrote in Berlin: “The story of the three journeyman carpenters, who all did the right thing and therefore could not coexist . Costume of the 18th century. “ The idea that a society made up of all the seeds of virtue does not stick together and that mere doing justice - the exercise of secondary virtues in today's parlance - has a destructive effect can be traced back to the writings of the early Enlightenmentist Pierre Bayle , which Keller used during his Heidelberg student days through Ludwig Feuerbach came into contact.

In preparing the narrative chose Keller the costume of the time closer Biedermeier and replaced the carpenter journeyman by Ka mmm acher, not least for the sake of three-triple jagged typeface. Both changes are related to the introduction of the fourth main character, Züs Bünzlin. Because more clearly than other trades, the manufacturers of combs are in the service of female vanity . In addition, it was for the moral speechify a model that the basement of the maid satirical wanted to meet: the stories of the Biedermeier clergyman and writer Christoph von Schmid . This well-read author of young books is mentioned in the text as one of the Züs sources of wisdom: She also owned some of the pretty stories by Christoph Schmid and his little story with the nice verses at the end .

reception

The way in which the narrator illustrates the character and past of his characters has always been widely discussed and admired in cellar literature. To do this, he spreads out the things they keep and tells their origin ( ekphrasis ). The description of the valuables, books and pledges in Züs' lacquered drawer extends over several printed pages. Without tiring the reader it starts at Gültbrief is through various knick-knacks , such as the famous candy-box of lemon peel, a strawberry painted on the lid , and ends at a Chinese temple made of cardboard, carefully manufactured by a bookbinder journeyman. The virgin enjoyed his friendship and advertising for over a year, but gave him the pass because of his youth and poverty, albeit with selectively pleasant speeches. The farewell, who had never had a word with her, left her the most beautiful letter in a double bottom of the little work of art , wet with tears, in which he expressed his unspeakable sorrow, love, admiration and eternal loyalty, and in such pretty and uninhibited words how she can only find the true feeling that has got lost in an alleyway . But since she had no idea of the hidden treasure, it happened here that fate was fair and a false beauty did not see what she did not deserve to see.

Another highlight of the novella is - not always - the description of the desperate race between Jobst and Fridolin in contrast to the cruel merriment it arouses in the Seldwylers:

- Both were covered in sweat and dust, they opened their mouths and longed for breath, saw and heard nothing that was going on around them, and thick tears rolled down the faces of the poor men, which they did not have time to wipe. They were hot on their heels, but the Bavarian was a margin ahead. Terrible screams and laughter rose and boomed as far as the ear could reach. […] The gentlemen in the gardens were standing on the tables and wanted to pour themselves out with laughter: But their laughter boomed thunderously and firmly over the unstoppable noise of the crowd that was encamped in the street, and gave the signal for an unheard of joyous day. The boys and the rabble flocked behind the two poor fellows, and a wild crowd, causing a terrible cloud, rolled with them towards the gate; [...] all the windows were occupied by the ladies, who threw their silver laughter into the roaring surf, and it was a long time since one had been so happy in this city.

With the epithet "thunderous and firm" the narrator alludes to Homeric laughter , but does not agree. In fact, at no other point in the cycle does Keller treat Seldwyler cosiness with greater coldness and distance: whether the mob, whether city gods or goddesses, they joke with horror. He was promptly reproached for the cruelty of his description and the bad end of the story. In the Grenzbote , a critic regretted a few years after Keller's death: "Nowhere a cure, nowhere a reconciliation, and so we are only now aware that this [...] novella is consistently bitter as its ending". He saw the reason for this "in the striking lack of temperament in Keller" - as if the satirist had invented the bad and base that he denounced himself and brought it into the world.

Jakob Baechtold , Keller's first biographer, reports: "The most dearest among his Seldwyler creatures remained for the poet The Three Just Comb-Makers, whose appreciation he always made the touchstone of his assessors." Keller wrote ironically to a friend in Berlin: "Your Dr. I don't know Horwitz; but since he is taken for the comb maker , he is in any case a very educated man and much smarter than Prutz and Gutzkow , who declared that Schnurre to be bad jokes. ” Richard Wagner , who associated with Keller during his years in Zurich, passed the test . Wagner, writes Baechtold, not without astonishment, “loved above all - The three just comb makers. “A Viennese friend, Marie von Frisch , was honored by Keller for his photograph with the dedication “ Portrait of the pious young man but unjust comb maker Gottfried Keller ”.

realism

"The novel should seek the German people where their ability can be found, namely in their work." That was the motto of the novel Soll und haben by Gustav Freytag , published in 1855 . It is unknown whether Keller took notice of Freytag's great success when he wrote “The Three Just Comb Makers” that same year and promoted it to print. Nevertheless, the coincidence of literary history is remarkable: Using the example of the Three Righteous, Keller shows the other side of work ethic and efficiency, not just the German. “Without any knowledge of Marxist political economy, ” wrote the East German literary scholar Hans Richter in 1961, “and without a doubt without any real intention, the realist Keller demonstrates the indissoluble contradiction between capital and labor using a concrete example. [...] In all of the German literature of Keller's time there is hardly any comparable design of this fundamental contradiction in capitalist society; that it is to be found with Keller, who, according to the still popular opinion, tells bourgeois, idyllic purrs, should not surprise the unprejudiced and thorough reader of this poet. "

grotesque

In the West, the reassessment of the Kammmacher novella took place at the same time under the aspect of grotesque humor to which Walter Benjamin had already drawn attention. Wolfgang Kayser introduces his work The Grotesque in Painting and Poetry with a summary of the Kammmacher novella and then repeatedly comes up with The People of Seldwyla to speak: "Keller [...] develops its own style of the grotesque. One may speak of realism with him, but then one must not fail to recognize that the uncanny, incomprehensible dark forces belong to the reality of his world and that the narrator, as deeply as his clear gaze penetrates and as much as he loves to smile cheerfully and To awaken a smile, the horror of the abysmal is not alien. ”(For Kayser, the design of the grotesque is“ the attempt to banish and conjure up the demonic in the world. ”)

Realist or Poet? As for the lack of intent in the design, Keller would have agreed with Richter. In his fictional town of Seldwyla he brought together characters who, as observation taught him, really did exist in the world, and allowed them to enter into equally worldly social relationships: competition, love, the pursuit of property and status. His stories are similar to thought experiments or model calculations . He often wondered about the results himself. On the other hand, as far as the “inconceivably dark” is concerned, he would probably not have agreed with Kayser's definition of the grotesque. Keller did not believe in supernatural beings. Züs Bünzlin is not a demon , but a person in whom natural self-love is so excessively developed that it becomes a lust for self-esteem and domination and drives out the need to dominate at all times . Keller discovered role models for such people primarily in the milieu of the highly educated. After reading a book that brought back memories of the Berlin salons, he wondered: “Only now do I know what an ideal I had in mind during the speeches of Züs Bünzlin, [...] especially when saying goodbye on the heights . When I wrote, I also kept an eye on women of high standing, but I didn't believe that it would go that high. "

literature

Text:

- Gottfried Keller: The three just Kammacher. Novella . Reclam, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-15-006173-3

Representations:

- Hans Richter: Gottfried Keller's early novels . Rütten and Loening, Berlin 1960

- Klaus-Dieter Metz: Gottfried Keller, the three just comb makers. Interpretation . Oldenbourg-Verlag, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-486-88640-1

Individual evidence

- ↑ In italics : literal quotations based on the text by Gottfried Keller: Complete Works , ed. by Jonas Fränkel , Zurich and Munich 1927, vol. 7, pp. 257–319.

- ↑ Quoted from Fränkel's editorial commentary, Complete Works , Vol. 7, p. 400.

- ^ After a verbal communication from Keller to Conrad Ferdinand Meyer , the Kammmacher novella was inspired by Bayle's thesis in the Dictionnaire historique et critique that a state of all righteous people could not exist. The exact location has never been proven (see Fränkel's comment, p. 400). However, in a Feuerbach book about Bayle, Hans Richter found quotes that make a similar sense (cf. Gottfried Keller's early novels , Berlin 1960, p. 144 f.)

- ↑ Schmids Instructive Little Stories for Children are available as digital copies . The first names of the comb makers are also taken from a Schmid story: The good Fridolin and the bad Dietrich. An instructive story for the elderly and children , which also includes a Jost (at Keller Jobst). The irony with which this type of story is called “pretty” was first noticed in the Keller literature by Hans Richter, cf. Gottfried Keller's early novellas , p. 146 ff.

- ↑ Die Grenzboten , Leipzig 1897, vol. 56, vol. 1, p. 537, quoted from Hans Richter: Gottfried Kellers early Novellen , p. 142, where other uncomprehending and derogatory reactions are discussed.

- ↑ Jakob Baechtold: Gottfried Keller's life, his letters and diaries , 3 volumes, Berlin 1894-97, vol. 2, p. 96.

- ^ To Lina Duncker, late June or early July 1858, Carl Helbling (ed.): Gottfried Keller. Collected letters . 4 volumes. Benteli, Bern 1950–54. Vol. 2, p. 171.

- ↑ Gottfried Keller's Life , Vol. 2, p. 309.

- ↑ Due to the genesis of the Kammmacher novella, it can be ruled out that it was directed against Freytag's novel or his motto originating from Julian Schmidt .

- ↑ Gottfried Keller's early novels , p. 153 f.

- ↑ See The People of Seldwyla # Humor .

- ↑ The grotesque in painting and poetry , rowohlts deutsche enzyklopädie ed. by Ernesto Grassi , Stuttgart 1960, p. 86 and p. 139.

- ↑ To Emil Kuh , June 9, 1875, Collected Letters , Vol. 3.1, p. 193.