Materialism dispute

The dispute over materialism was a mid-19th century controversy about the ideological consequences of the natural sciences . Influenced by the methodological renewal of biology and the decline of idealistic philosophy , a materialism was formulated in the 1840s that claimed to explain man scientifically. At the center of the controversy was the question of whether the results of the natural sciences are compatible with the concept of an immaterial soul , a personal God and free will . In addition, the debate focused on the epistemological prerequisites of a materialistic worldview.

In the Physiological Letters from 1846, the zoologist Carl Vogt explained that "thoughts are in the same relationship to the brain as the bile to the liver or urine to the kidneys." Rudolf Wagner was critical in a speech to the Göttingen natural scientists meeting. Wagner argued that Christian faith and natural science formed two largely independent spheres. The natural sciences could therefore not contribute anything to the question of the existence of God, the immaterial soul, or free will.

"One must not always let it go when this frivolous rabble wants to cheat the nation out of the dearest goods inherited from our fathers and shamelessly blow the stinking breath at the people from the fermenting contents of its entrails and want to make them know that it is vain fragrance. "

Wagner's attacks provoked equally sharp reactions from Vogt, whereby the materialistic point of view was defended in the following years by the physiologist Jakob Moleschott and the doctor Ludwig Büchner , a brother of the well-known writer Georg Büchner . The materialists presented themselves as champions against the philosophical, religious and political reaction , although they set quite different accents, and could count on broad support from the bourgeoisie . The promise of a scientific worldview developed into a formative element of the cultural conflicts of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Development of scientific materialism

Emancipation of biology

The emergence of popular materialism was facilitated by a "polemic against romantic idealistic natural philosophy that became commonplace after 1830 ", which had an impact on science, philosophy and politics alike.

From a scientific-historical perspective , the cell theory founded by Matthias Jacob Schleiden in particular proved to be momentous. In the articles on phytogenesis published in 1838 Schleiden declared the cell to be the basic building block of all plants and also identified the cell nucleus, discovered in 1831, as an essential factor in plant growth. The cellular theory of the structure of plant organisms meant a substantive reorientation of botany , which until then had been mainly characterized by the macroscopic description of forms. At the same time Schleiden linked his theory about the structure of plants with a methodological attack on idealistic natural philosophy. The cell theory is based on empirically verifiable observation , because "a person controls only as many facts about the objects of physical natural sciences as he has observed himself." - and theorists are thrown aside ”.

Schleiden's program of methodically renewed botany was transferred to other biological disciplines in the following years. As early as 1839 Theodor Schwann published his microscopic studies on the correspondence in the structure and growth of animals and plants . Schwann explained that the cell theory reveals the general principle of life . All living things are made up entirely of cells, and the formation of organs can be explained by the growth and multiplication of cells. In this context, Rudolf Virchow proclaimed: “In its essence, life is cellular activity.” The cell theory thus opened the perspective of a scientific theory of life on which the materialists could build a few years later.

Turning away from idealistic philosophy

Parallel to the methodological realignment of the biological disciplines, a general criticism of the conservative legacy of German idealism developed in the intellectual climate of Vormärz . In the natural sciences themselves, criticism of the natural philosophical methodology remained moderate, and many biologists remained resolute anti-materialists. In contrast, philosophical movements emerged only a few years after Hegel's death in 1831, which also radically broke with German idealism in ideological terms.

The criticism of religion , as formulated by Ludwig Feuerbach in the essay The Essence of Christianity , was of particular importance and socially explosive . Feuerbach had studied with Hegel in Berlin from 1824, attended each of his lectures for two years and wrote traditionally idealistic texts until the 1830s. Nevertheless, doubts developed among Feuerbach and many other young Hegel students. The Young Hegelians were not only suspicious of the political conservatism of German idealism, but at the same time the system philosophy, which was detached from empirical observations , seemed increasingly wrong. In 1839 Feuerbach was finally ready to criticize his teacher in principle. Hegel's idealistic system may be coherent and conclusive, but it has distanced itself from sensuous nature in an impermissible way. The philosophy must start in the sensibly given, just so they could come to a knowledge of nature and reality. "Vanity is therefore all speculation that wants to go beyond nature and man." The idea of a view of nature emancipated from speculation was shared by Feuerbach and the new biological movements. But Feuerbach's goal was an anthropological and not a scientific theory of man.

What explosive Feuerbach's anthropology contained became clear in his religious philosophy . Idealistic philosophy made the mistake of proving the truth of theological teachings in abstract arguments. In reality, however , religion is not a metaphysical truth, but an expression of human needs . Theologians and philosophers could not prove the existence of God, since God is an invention that results from the "nature of man". Feuerbach's argument was not directed against religions in general; there are definitely good reasons for religious belief . These reasons, however, are psychological in nature, and religions satisfy real human needs. In contrast, philosophical-theological proofs of the existence of God are speculative fantasies. Feuerbach's criticism of religion was received as a radical attack on the cultural establishment; by the mid-1840s it had become the center of the philosophical renewal movements.

Carl Vogt and the political opposition

The materialistic theses of the physiologist Carl Vogt published from 1847 onwards provided the external cause of the materialism dispute. Vogt's turn to materialism was largely shaped by the scientific and cultural renewal movements, but his political development played an at least as important role. Born in Gießen in 1817 , Vogt grew up in a family that combined scientific and social revolutionary tendencies. Carl's father, Philipp Friedrich Wilhelm Vogt, was a medical professor in Gießen until he accepted a professorship in Bern in 1834 due to the threat of political persecution . The political entanglements were in the tradition of the maternal family, the three brothers Louise Follens were all forced to emigrate because of their nationalist and democratic activities.

In 1817, Adolf Follen wrote the basics for a future imperial constitution and was arrested two years later for "German activities". The Swiss exile saved him from ten years of imprisonment. Karl Follen defended the murder of tyrants in a leaflet and was therefore considered the intellectual author of the assassination attempt on the writer August von Kotzebue . He managed to escape to the United States , where he established himself from 1825 as a professor of the German language at Harvard University . Paul Follen , the youngest of the brothers, founded the Giessen Emigration Society with Friedrich Münch in 1833 . The goal of a German republic in the United States failed, Paul Follen settled as a farmer in Missouri .

Carl Vogt began studying medicine in Gießen in 1833, but soon turned to chemistry with Justus Liebig . Liebig's experimental methods were in explicit contrast to idealistic natural philosophy. As a co-founder of organic chemistry , Liebig rejected a separation between living processes and dead matter and thus offered Vogt an intellectual prerequisite for the later developed materialism. In 1835, however, political circumstances made it impossible to continue studying in Giessen. News that he helped a politically persecuted student escape made him a target for the police himself. Vogt then emigrated to Switzerland , where he graduated from the medical faculty in 1839 .

In the early 1840s Vogt had come into contact with the political opposition and the new scientific movements, but had not yet developed his ideological materialism. This changed during his three-year stay in Paris, which contributed significantly to Vogt's political and ideological radicalization . The acquaintance with the anarchists Michail Bakunin and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon had a lasting impact on Vogt's political thinking. From 1845 he also began to publish his Physiological Letters , with which he published a generally understandable description of physiology based on Liebig's Chemical Letters .

The first letters did not contain any references to Vogt's materialism, it was only in the letter on nerve power and soul activity published in 1846 that Vogt declared "that the seat of consciousness , will , and thought must finally be sought solely in the brain ".

At first, however, political practice took precedence over materialistic theory. Vogt had just been appointed professor of zoology in Giessen through the influence of Liebig and Alexander von Humboldt when the German Revolution began in March 1848 and democratic forces rose against the so-called reaction in various parts of Germany . When this March revolution , the small university town reached casting, Vogt was commander of the vigilante appoint and finally took the sixth constituency Hesse-Darmstadt in the Frankfurt National Assembly from 1848 to 1849. After the Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm IV. The offered to him imperial dignity had rejected and political defeats led to the breakup of the National Assembly, Vogt moved with the remaining 158 members to Stuttgart to form the so-called rump parliament at the beginning of June 1849, which was forcibly dissolved after just a few weeks .

Appointed by this remaining parliament to one of the “five Reich regents”, Vogt found himself at the center of the political opposition. Wuerttemberg troops occupied the conference venue on June 18 of that year . Vogt emigrated to Switzerland and took refuge in his parents' house. Failed in his political ambitions and robbed of his academic career, he concentrated again on biological studies, which he now interpreted radically as ideological.

course

Materialism dispute until 1854

Without clear academic perspectives, Vogt went to Nice in 1850 to devote himself to zoological studies. His studies on animal states , published the following year, combined zoology with a bitter reckoning with German conditions. Politically, the book was a plea for anarchism, "every form of government, every law [is] a sign of the inadequate perfection of our natural state ". Vogt's biological argument for anarchism was based on the conviction that animal and human states are in continuity with one another, since humans are also natural and completely material organisms. In Vogt's view, biology implied both materialism and the subversion of the ruling order. In his book he made clear reference to the German situation :

“So go there, you little book, as old truth in a new guise. Pilgrimage around in that unhappy land whose language you speak, but whose meaning will hardly meet you. "

In fact, Vogt managed to arouse the interest of the German public with his popular and polemical attacks. In 1852 the pictures from animal life appeared , in which Vogt not only offered a detailed account of materialism, but at the same time sharply attacked the German university scholars. Every clearly thinking biologist must recognize the truth of materialism, since the dependence of the soul functions on the brain functions is obvious. This dependency is shown most clearly in animal experiments, so "we can cut off the mental functions of the pigeon bit by bit by removing the brain bit by bit". But if the soul functions depend on the brain in this way, the soul cannot survive the death of the body either . And if the brain functions by the laws of nature determined were, the same should also apply to the soul.

“So the gates and gates would be open to simple materialism - man as good as the animal is just a machine, his thinking the result of a certain organization - free will therefore abolished? […] Verily, that's how it is. It really is like that."

In Vogt's opinion, anyone who did not want to agree to these statements had not understood the necessary consequences of physiological research. This particularly affected the anatomist and physiologist Rudolf Wagner from Göttingen , who in 1851 criticized Vogt in the Augsburger Allgemeine Zeitung for replacing God with a "blind, unconscious necessity". At the same time he had thought that the soul of a child was composed in equal parts of the soul of the mother and the father. This idea offered Vogt a welcome template. A composite child's soul not only contradicts the theological conception of the indivisibility of the soul , but is also physiological nonsense. Physical characteristics such as facial features are naturally inherited from parents to children . The same applies to the brain, which is why the inheritance of character traits can easily be explained materialistically.

Göttingen Naturalists' Meeting

In the summer of 1854, the 31st meeting of naturalists in Göttingen offered Wagner the opportunity to make a highly publicized reply. In his lecture on human creation and soul substance , Wagner accused the materialists of undermining the moral foundations of the social order by denying free will.

“We, who are gathered here, no matter how different our worldview may have developed in each individual of us, we who have seen, felt, and for the most part participated self-consciously with the struggle of our nation in its last struggles, we have to suggest to us what the results of our research will be for the education and future of our great people. "

Vogt's materialism runs counter to the researcher's moral responsibility, since it turns people into blind and irresponsible machines. In the same year, a second work by Wagner appeared in which he supplemented the moral allegations with a general argument on the relationship between knowledge and belief. According to Wagner, these two largely independent areas, no scientific knowledge can consequently prove or disprove religious belief.

Physiologists would describe the internal structure and function of the bodily organs, materialists would interpret these descriptions by identifying the physical and mental functions with one another. Dualists , on the other hand, assumed that the physical functions acted on an immaterial soul. Neither of the two interpretations result from the physiological description, which is why the natural sciences cannot decide the soul question. "There is not a single point in the biblical doctrine of the soul [...] which would contradict any of the tenets of modern physiology and natural science."

Faith in coal and science

Wagner's high-profile polemics had finally moved the debate on materialism, which had been simmering for several years, into the center of public interest. Vogt responded promptly with the pamphlet “ Köhlerlaube und Wissenschaft”. A polemic against Hofrath Rudolph Wagner in Göttingen. The first half of the text is largely shaped by drastic ad hominem attacks against Wagner. He is not a serious and productive scientist, but rather adorns himself as the editor of countless works with the research of others. He also tried to suppress his materialistic critics with the help of the state. Vogt's particular anger aroused Wagner's assertion that the materialistic denial of free will in view of the political events of 1848 (March Revolution) was socially irresponsible:

“Pathetic wretch! Where did you struggle, feel, take with you on one side or the other? [...] We have not seen you, neither in the ranks of our enemies nor in those of our friends, and we can call out to you with the poet: 'Ugh about you, boys behind the stove.' "

In the second part of the thesis, Vogt argued more systematically against Wagner's thesis of the compatibility of “naïve belief in charcoal” and scientific knowledge. Anyone who puts the soul in an area beyond any empirical verifiability can no longer be directly refuted by physiology, but makes a completely useless and ultimately even incomprehensible assumption. The dependence of the soul functions on the brain functions clearly speaks for an identity of body and soul and cannot be ignored by the axiom of an immaterial soul. This is accepted by Wagner for all organs except for the brain. Even Wagner does not claim that in addition to the biological processes in the muscles there is a muscle soul that causes the muscle contraction . Nor would he claim that in addition to the biological processes in the kidneys, there is a kidney soul that causes the excretion of metabolic products . “Only with the brain one does not want to acknowledge this; only with this one wants to allow a special illogical conclusion that is not valid for the other organs to occur ”.

Food, strength and matter

Vogt's polemical theses might meet with strong resistance in the academic and political environment, but the commitment to materialism had long since developed into an influential movement in 1855. Vogt received support from two younger scientists, Jakob Moleschott and Ludwig Büchner , who also publicized their materialistic theses in popular scientific publications. This rhetorically stylized these three authors as the pioneers of a seemingly coherent materialism, and in this escalation the material dispute itself became a catalyst for a controversially discussed intensification of popularization efforts and of ideological debates about the relationship between natural research and society, which had been taking place since the end of the 1850s the discussion of Darwinian evolution passed over.

Jakob Moleschott, born in 's-Hertogenbosch in the Netherlands, in 1822 , came into contact with Hegel's philosophy early on, but finally decided to study medicine in Heidelberg . Strongly influenced by Feuerbach's philosophy, he dealt with questions of metabolism and diet . According to Moleschott's materialistic beliefs, food appeared to be the basic building blocks of physical and mental functions. In his book The Doctrine of Food: For the People , Moleschott endeavored to popularize his studies and presented detailed diet plans for the impoverished sections of the population. Materialism should not only negatively deny the existence of an immaterial soul and God, it should positively lead people to a better life.

In 1850, Moleschott sent a copy of his work to Feuerbach, who in the same year published an influential review entitled Science and the Revolution . In the 1840s, Feuerbach had defined his philosophy beyond idealism and materialism, now he took an explicit position for the materialists. While the philosophers continued to argue in a sterile way about the relationship between body and soul, the natural sciences would have long since found the answer:

“The food becomes blood, the blood becomes heart and brain, thoughts and sentiments. Human food is the basis of human education and attitudes. If you want to improve the people, give them better food instead of declamations against sin. You are what you eat."

Büchner's alliance with the public proved to be even more influential than Moleschott's alliance with Feuerbach. Büchner, born in Darmstadt in 1824 , had already come into contact with Vogt as a student and in 1848 became a member of the vigilante group led by Vogt. After some unfortunate years as an assistant at the medical faculty in Tübingen , Büchner decided to publish a catchy summary of the materialistic worldview. Kraft und Stoff developed into a bestseller, 12 editions appeared in the first 17 years and the book was translated into 16 languages. In contrast to Vogt and Moleschott, Büchner did not present materialism in the context of his own research, but offered a summary of the findings that were understandable even without previous philosophical or scientific knowledge. The starting point was the unity of force and matter, already emphasized by Moleschott . No matter could exist without inherent forces, no force without matter as a carrier. The impossibility of immaterial souls immediately follows from this unity, since these would have to exist without a material carrier.

Reactions in the 19th century

Philosophy of Neo-Kantianism

Materialism was borne by natural scientists such as Vogt, Moleschott and Büchner, who presented their theses as the consequences of empirical research. The University philosophy seemed discredited as baseless speculation with the collapse of German idealism. Even the philosopher Feuerbach now trusted the natural sciences to solve the philosophical question of the relationship between soul and body.

It was not until the 1860s that an influential philosophical critique of materialism developed with Neo-Kantianism . In 1865 Otto Liebmann had sharply criticized the philosophical approaches from German idealism to Schopenhauer in his book Kant and the Epigones and closed every chapter with the statement "So we have to go back to Kant!" In keeping with this position, the philosopher Friedrich Albert Lange published his History of Materialism the following year . With reference to Kant, Lange accused the materialists of “philosophical dilettantism”, which ignored essential knowledge of Kant's philosophy .

The central theme of the Critique of Pure Reason was the question of the conditions of every possible - including scientific - knowledge. Kant had argued that human knowledge does not depict the world as it really is. Every knowledge is already characterized by categories such as “cause and effect” or “unity and diversity”. These categories are not properties of things in themselves , but are brought to things by people. In the same way, space and time also have no absolute reality, but are forms of human perception. Since every knowledge is already shaped by the categories and the forms of perception, man can never know the things in themselves. Therefore answers to the questions about an immaterial soul, a personal God and a free will cannot be scientifically proven.

The main mistake of the materialists, according to Lange, was their ignorance of Kant. Materialism asserts that there is only matter in reality and overlooks that the scientific description of matter is in no way a description of absolute reality . The scientific description already presupposes the categories and forms of perception and can therefore in no way be regarded as a description of things in themselves. Lange received support in this line of argument from the natural scientist Hermann von Helmholtz , of all people , who had presented his sensory-physiological work in the 1850s as an empirical confirmation of Kant's work. In the lecture on human vision given in 1855, Helmholtz first described the physiological foundations of visual perception and then explained that vision does not represent a true-to-life image of the outside world. In the Kantian sense, every perception of the outside world is already shaped by human interpretations, and access to things in themselves is consequently impossible:

“But as it is with the eye, so it is with the other senses; we never perceive objects in the outside world directly, we only perceive the effects of these objects on our nervous system. "

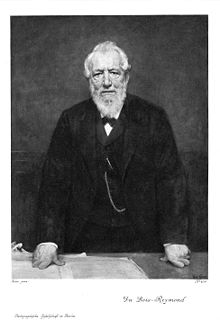

Ignoramus et ignorabimus

The scientific materialists saw in the reference to Kant only another, speculative attack on the results of the natural sciences and therefore did not deal systematically with the arguments of the Neo-Kantians. Dangerous appeared criticism of the physiologist Emil du Bois-Reymond , who in 1872 in his lecture About the limits of Naturerkennens the consciousness explained to a fundamental limit of the natural sciences. With his dictum Ignoramus et ignorabimus (Latin: “We don't know and we will never know”) he sparked a long-lasting controversy about the idea of a scientific worldview. The so-called ignorance controversy was fought out with as vehemence as the debate between Vogt and Wagner 20 years earlier, and was carried even more into the political arena. This time, however, the materialists were on the defensive.

According to du Bois-Reymond, the materialists' main problem was their inadequate reasoning for the unity of mind and soul. Vogt, Moleschott and Büchner had limited themselves to emphasizing the dependence of soul functions on brain functions. Damage to the brain leads to impairment of mental functions, as can be proven experimentally in animal experiments . However, this dependency makes the idea of an immaterial soul implausible and consequently materialism is the only acceptable consequence. It is therefore not even necessary to explain how the brain ultimately generates consciousness:

“Besides, for the purpose of this investigation it can appear quite indifferent whether and in what way an idea is possible as to how the mental phenomena arise from material connections or activities of the brain substance, or how material movement changes into spiritual. It is sufficient to know that material movements act on the mind through the mediation of the sense organs . "

Du Bois-Reymond, on the other hand, argued that evidence of dependency relationships is by no means sufficient for materialism. Anyone who wants to reduce consciousness to the brain must also explain consciousness through brain functions. The materialists could not offer such an explanation: "What conceivable connection exists between certain movements of certain atoms in my brain on the one hand, and on the other hand the original, indefinable, indisputable facts" I feel pain, feel pleasure; I taste sweet things, smell the scent of roses, hear the sound of an organ, see Roth. '”According to du Bois-Reymonds, there is no conceivable connection between the objectively described facts of the body world and the subjectively determined facts of conscious experience . Consciousness therefore describes a fundamental limit to the knowledge of nature.

Du Bois-Reymond's Ignorabimus speech seemed to indicate a fundamental weakness in scientific materialism. While Vogt, Moleschott and Büchner claimed the materiality of consciousness, they openly admitted that they could not explain consciousness through brain functions. Not least under the influence of this problem, the concept of a scientific worldview developed from materialism to monism towards the end of the 19th century . Ernst Haeckel , the best-known representative of a “monistic worldview”, agreed with the materialists in rejecting dualism, idealism and the idea of an immortal soul.

“Monism, on the other hand, recognizes only one substance in the universe, which is God and nature at the same time; Body and spirit (or matter and energy) are inseparable for them. "

Haeckel's monism differs from materialism, however, because he does not give matter any priority; body and mind are inseparable and equally fundamental aspects of a substance . Such a monism seemed to circumvent du Bois-Reymond's problem. If matter and mind are equally fundamental aspects of a substance, then mind no longer needs to be explained by matter.

Büchner, too, saw such a monism as the correct response to the philosophical criticism of materialism. In a letter to Haeckel from 1875 he wrote:

"I [...] therefore never used the term 'materialism', which arouses a completely one-sided idea, for my direction and only necessarily accepted it here and there later because the general public knew no other word for the whole direction [...] . The term 'monism' you suggested is in itself very good; the question arises, however, whether it will continue to gain acceptance with the large audience. "

Political and ideological impact

The materialists might have become very popular with the population, but politically they were far less successful. The advocacy of materialism cost Vogt, Moleschott and Büchner their careers at German universities. The revolutionary content of materialism propagated by Vogt could not assert itself in the reaction era after 1848. In the political movements of the second half of the 19th century, scientific materialism also had no significant influence, also due to differences with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels . Vogt was described by Marx as a “small- university beer rumbler and missed Reichs barrot ” and the conflicts increasingly escalated into personal denunciations. For example, Vogt from Marx's circle was confronted with the charge of having worked as a French spy.

The changed political situation is also clear in the work of Ernst Haeckel, who adopted the idea of a scientific worldview from the materialists, but gave it a new political direction. Haeckel, 17 years younger than Vogt, established himself as a representative of Darwinism in Germany in the 1860s . In his polemical rejection of "church wisdom and [...] after-philosophy", Haeckel resembled the scientific materialists. Vogt saw the beginning of a scientific worldview in physiology. Haeckel claimed the same with regard to Charles Darwin :

“In this spiritual battle, which now moves all thinking humanity and which prepares a humane existence in the future, stand on the one hand under the bright banner of science: spiritual freedom and truth, reason and culture, development and progress ; on the other hand under the black flag of the hierarchy: mental bondage and lies, irrationality and rudeness, superstition and regression. "

But Haeckel's “progress” was essentially anti-clerical in opposition to the church and not politically in opposition to the state. Bismarck's cultural struggle against the Catholic Church, which began in 1871, even offered Haeckel the opportunity to link anti-clerical monism with Prussian politics . In the run-up to the First World War , Haeckel's statements became increasingly nationalistic , while racial theories and eugenics offered a seemingly scientifically based justification for chauvinistic politics. Vogt's ideal of a politically revolutionary natural science had thus finally failed.

Reception in the 20th century

Scientific materialism had shaped the ideological controversies in the 19th century. In the 1860s the debates about Darwin's theory of evolution and Haeckel's monism increasingly came to the fore. The question of a scientific worldview continued to be controversial, however, and Büchner's strength and substance remained a bestseller.

An incision meant the First World War and the death Haeckel 1919. In the Weimar Republic did not seem the debates of the 1850s of date, the philosophical currents of the interwar period were all materialism critical in all substantive differences. This also applies to Logical Positivism , which, although adhering to the idea of a scientific world view, interpreted it consistently in an anti-metaphysical way . According to the criterion of meaning of the logical positivists, a statement was only understandable if it could be empirically verified. Materialism and monism failed because of this criterion, as did idealism and dualism. All of these positions thus appeared to be misguided fantasies of a bygone speculative epoch of philosophy. Materialistic theories of consciousness were not taken up again until the 1950s in Anglo-Saxon philosophy. During this time, however, the natural scientific materialists of the 19th century had finally been forgotten. No reference is made to Vogt, Moleschott or Büchner in any of these texts; the materialists of the post-war period concentrated on contemporary neurosciences .

Even science - and the history of philosophy of scientific materialism was largely ignored until the 1970s. Reception in the GDR began relatively early under the influence of Dieter Wittich , who received his doctorate in 1960 with a thesis on scientific materialists and in 1971 published a text collection at Akademie Verlag under the title Vogt, Moleschott, Büchner: Writings on petty bourgeois materialism in Germany . Wittich, holder of the only chair for epistemology in the GDR, praised the political, scientific and religious-critical work of the materialists in his detailed introduction. At the same time, however, he emphasized their philosophical shortcomings, the "petty-bourgeois materialists" were "vulgar materialists because they insisted on metaphysical materialism at a time when dialectical materialism had become not only a possibility but also a reality."

In 1977 the monograph Scientific Materialism in Nineteenth Century Germany by the American science historian Frederick Gregory was published , which is still regarded as a standard work today. According to Gregory, the importance of Vogt, Moleschott and Büchner is less to be sought in their specific elaboration of materialism. The social impact of her scientifically motivated criticism of religion, philosophy and politics was more decisive. "From a historical perspective, the outstanding characteristic of the scientific materialist was not their materialism, but their atheism, or more appropriately their humanistic religion."

According to Gregory's judgment, the importance of the materialists in the secularization process of the 19th century is generally recognized in the current research literature, while their philosophical positions are in part still subject to severe criticism. Renate Wahsner , for example, explains : "The view expressed in literature cannot be contradicted, which denies all three sharpness and depth in thinking". Not all authors share this negative assessment. Kurt Bayertz , for example, defends the topicality of the scientific materialists, since they developed “the first fully developed form of modern materialism”. "With the form of materialism developed by Vogt, Moleschott and Büchner, we are only dealing with one form of materialism, but with the most influential and effective form that is typical of modernism and the most influential and effective at the present time." start in the 19th century.

literature

- Primary literature

- Ludwig Büchner : Kraft und Stoff ( Kröner's pocket edition ; 102). Kröner Verlag, Leipzig 1932 (reprint of the first edition Darmstadt 1855).

- Friedrich Albert Lange : The history of materialism and criticism of its significance in the present . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt / M. 1974, ISBN 3-518-07670-1 (2 vols .; reprint of the first edition Berlin 1866).

- Jakob Moleschott : The cycle of life . 5th edition Zabern, Mainz 1877.

- Carl Vogt: Physiological letters, 14th edition. Rickersche Buchhandlung, Giessen 1874.

- Carl Vogt: belief in coal and science. A polemic against Hofrasth Rudolph Wagner in Göttingen . 4th edition Rickersche Buchhandlung, Giessen 1856.

- Rudolf Wagner: About knowledge and belief. With a special relationship to the future of souls. Continuation of the consideration about "human creation and soul substance" . GH Wigand, Göttingen 1854.

- Rudolf Wagner: Human creation and soul substance. An anthropological lecture . GH Wigand, Göttingen 1854.

- Dieter Wittich : Vogt, Moleschott, Büchner. Writings on petty-bourgeois materialism in Germany . Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1971 (only available collection of texts on 19th century materialism)

- Karl Vogt, Physiological letters for educated people of all classes. Jakob Moleschott, The cycle of life . 1971. LXXXII, 344 pp.

- Ludwig Buchner, strength and substance. Karl Vogt, belief in coal and science . 1971. pp. 348-657.

- Secondary literature

- Andreas Arndt, Walter Jaeschke (ed.): Materialism and Spiritualism. Philosophy and Sciences after 1848 . Meiner, Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-7873-1548-9 .

- Kurt Bayertz , Walter Jaeschke, Myriam Gerhard (ed.): Weltanschauung, philosophy and natural science in the 19th century (The dispute over materialism; Vol. 1). Meiner, Hamburg 2007, ISBN 3-7873-1777-5 .

- Annette Wittkau-Horgby: Materialism. Origin and impact in the sciences of the 19th century . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1998, ISBN 3-525-01375-2 (plus habilitation thesis, University of Hanover 1997).

- Andreas W. Daum : Science popularization in the 19th century. Civil culture, scientific education and the German public 1848–1914. 2nd, supplementary edition, Oldenbourg, Munich 2002, ISBN 978-3-486-56551-5 .

- Frederick Gregory: Scientific Materialism in Nineteenth Century Germany . Reidel, Dordrecht 1977, ISBN 90-277-0760-X .

- Frederick Gregory: Scientific versus Dialectical Materialism. A Clash of Ideologies in Nineteenth-Century German Radicalism . In: Isis , Vol. 68 (1977), Issue 2, pp. 206-223.

- Theobald Ziegler : The intellectual and social currents of the nineteenth century . New edition Bondi, Berlin 1911, chapter 11.

- Steffen Haßlauer: Polemics and argumentation in the science of the 19th century. A pragmalinguistic investigation of the dispute between Carl Vogt and Rudolph Wagner about the "soul" . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2010. ISBN 978-3-11-0229943 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Physiological Letters , p. 323.

- ↑ About knowledge and belief , S.IV.

- ^ Andreas W. Daum: Science popularization in the 19th century. Civil culture, scientific education and the German public 1848–1914 . Oldenbourg, Munich 2002, p. 293-299 .

- ^ Herbert Schnädelbach: Philosophy in Germany 1831-1933 , Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a. M. 1883, p. 100

- ^ Matthias Jacob Schleiden: "Contributions to Phytogenesis" in: Archive for Anatomy , 1838, pp. 137–176.

- ^ Schleiden, quoted from: Annette Wittkau-Horgby: Materialismus. Origin and impact in the sciences of the 19th century , Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1996, p. 54f.

- ↑ Rudolf Virchow: "About the need and the correctness of medicine from the mechanical standpoint" in: Virchow's archive for pathological anatomy and physiology and for clinical medicine , issue 1, 1907 (1845) p. 8.

- ^ Walter Jaeschke: Philosophy and Literature in the Vormärz. The dispute over romanticism (1820–1854) , Meiner, Hamburg 1998.

- ↑ Cf. Scientific Materialism in Nineteenth Century Germany , pp. 13–28.

- ↑ Ludwig Feuerbach: "On the Critique of Hegelian Philosophy", in: Collected Works , Volume III, Akademie Verlag, Berlin, 1967–2007, p. 52.

- ↑ Cf. on this: Hermann Misteli: Carl Vogt: his development from the budding scientific materialist to the ideal politician of the Paulskirche (1817–1849) , Gebr. Leemann, Zurich 1938.

- ↑ Wolfgang Hardtwig: German history of the latest time. Pre-march . The monarchical state and the bourgeoisie , dtv, Munich 1997, p. 13ff.

- ↑ Liebig vehemently rejected materialism: Wilhelm Brock: Justus von Liebig. Vieweg, Wiesbaden 1999, p. 250.

- ^ Physiological letters. P. 322.

- ^ Carl Vogt: Studies on Animal States , Literary Institution, Frankfurt a. M. 1851, p. 23.

- ↑ Ibid., P. IX

- ↑ Carl Vogt: Pictures from the animal life , literary institution, Frankfurt a. M. 1852, p. 443.

- ↑ Ibid. P. 445.

- ^ Wagner quoted from: Andreas Daum, Wissenschaftspopularisierung im 19. Century. Civil culture, science education and the German public 1848–1914 , Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 1998, p. 295.

- ↑ Physiological Letters , pp. 452f.

- ↑ Human creation and soul substance , p. 25.

- ↑ About knowledge and belief , p. 30.

- ↑ Koehler belief and science , p. 10.

- ↑ Köhlerlaube und Wissenschaft , p. 111.

- ↑ Daum: Science popularization . S. 294-307 .

- ↑ Cf. Jacob Moleschott's autobiographical work: For my friends. Memoirs , Emil Roth, Giessen 1895.

- ↑ Ludwig Feuerbach: "The natural science and the revolution", in: Collected works. Volume X Akademie Verlag, Berlin, 1967-2007, p. 22.

- ↑ On Büchner, see: Michael Heidelberger: "Büchner, Friedrich Karl Christian Ludwig (Louis) (1824–99)", in: Edward Craig (Ed.): Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy , Routledge, London / New York 1998, p 48-51.

- ↑ Otto Liebmann: Kant and the Epigones. A critical treatise . C. Schobe, Stuttgart 1865.

- ↑ Friedrich Albert Lange: The history of materialism and criticism of its significance in the present . German Library, Berlin 1920, p. 31.

- ↑ Friedrich Albert Lange: The history of materialism and criticism of its significance in the present . German Library, Berlin 1920, p. 56.

- ↑ Hermann Helmholtz: About human vision . In: Hermann Helmholtz: Collected writings . Volume I, Olms, Hildesheim 2003, p. 115.

- ↑ Daum: Science popularization . S. 65-83 .

- ↑ Kraft und Stoff , p. 181.

- ^ Emil du Bois-Reymond: About the limits of nature knowledge, 1872, reprint u. a. in: Emil du Bois-Reymond: Lectures on Philosophy and Society, Hamburg, Meiner, 1974, p. 464

- ^ Ernst Haeckel: Die Weltträthsel , Kröner, Leipzig 1908, p. 13

- ↑ Büchner to Haeckel, March 30, 1875, in: Christoph Knockerbeck (Ed.): Carl Vogt, Jacob Moleschott, Ludwig Büchner, First Haeckel. Correspondence , Basiliken Presse, Marburg 1999, p. 145

- ^ Karl Marx: Herr Vogt , in: Marx-Engels-Werke , Volume 14, Dietz, Berlin 1961, p. 463

- ↑ See on this: Frederick Gregory: "Scientific versus Dialectical Materialism: A Clash of Ideologies in Nineteenth-Century German Radicalism", in: ISIS , 68 (2), 1977, pp. 206-223.

- ^ Ernst Haeckel: Anthropogenie , Wilhelm Engelmann, Leipzig 1874, S.IX.

- ^ Ernst Haeckel: Anthropogenie , Wilhelm Engelmann, Leipzig 1874, p. XII.

- ↑ An overview is provided by: Michael Heidelberger: "How the body-soul problem came into logical empiricism", in: Michael Pauen and Achim Stephan. (Ed.) Phenomenal Consciousness - Return to Identity Theory? , Mentis, Paderborn 2002, pp. 43-70.

- ↑ Ullin Place: “Is Consciousness a Brain Process?” In: British Journal of Psychology 47, 1956, pp. 44-50 and John JC Smart: “Sensations and Brain Processes” in: The Philosophical Review 68, 1959. p. 141 -156.

- ↑ An exception is Hermann Lübbe: Political Philosophy in Germany. Studies on its history , Schwabe, Basel 1963.

- ^ Dieter Wittich: The German petty bourgeois materialism of the reaction years after 1848/49 , dissertation, unpublished, Berlin 1960.

- ^ Vogt, Moleschott, Büchner: Writings on petty bourgeois materialism in Germany , S.LXIV

- ^ Scientific Materialism in Nineteenth Century Germany , p. 213.

- ↑ Renate Wahsner: "The concept of materialism in the middle of the 19th century", in: Kurt Bayertz, Walter Jaeschke, Myriam Gerhard (ed.): Weltanschauung, philosophy and natural science in the 19th century: Der Materialismusstreit , Volume 1. Meiner, Hamburg 2007, p. 73

- ↑ Kurt Bayertz: "What is modern materialism?", In: Kurt Bayertz, Walter Jaeschke, Myriam Gerhard (ed.): Weltanschauung, Philosophy and Natural Science in the 19th Century: Der Materialismusstreit , Volume 1. Meiner, Hamburg 2007, p. 55

Web links

- Digitized works by scientific materialists in the Internet archive

- Kurt Bayertz and Walter Jaeschke: The dispute over materialism (PDF; 29 kB)

- Rudolf Eisler : Article " Materialism " in: Dictionary of Philosophical Terms, 1904

- Ernst Krause: Vogt, Carl . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 40, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1896, pp. 181-189.

- Article on the dispute over materialism in the German Medical Journal, 2006