Natural state

The natural state of man is a central topic of discussion that deals with the philosophical debate that unfolded in the 17th century about the legitimation of the law set by humans and of society in its current state. The first participants in the discussion were Thomas Hobbes , Samuel von Pufendorf , John Locke , Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi , Anthony Ashley Cooper , the third Earl of Shaftesbury, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau .

The focus of the discussion is the person in the state before larger communities are being built.

The state of nature can be defined differently within the debate: Hobbes spoke of the " war of all against all ". Under this prerequisite, human culture is the makeshift, if not necessarily satisfactory answer to the catastrophic initial situation. It can just as easily acquire ideal traits, traits of a lost, happy naturalness to which we can no longer return or which, on the contrary, must set us the goal of further cultural development.

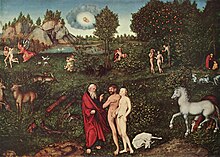

The theories about the state of nature ran (and run) at various points parallel to the biblical story of creation - this fact in particular made the debate explosive: it continued a previous discussion of religion in the field of philosophy. On the other hand, it has different branches in current scientific research with its areas of anthropology , ethnology and early human history .

History of the discussion

In terms of motif history, the discussion of the 17th and 18th centuries can be traced in different directions into the past. Antiquity developed a strong tradition of pleasant notions of nature as an alternative to the life of the city and the state. Those who could afford country houses. In poetry the happy life of the shepherds was celebrated. At the beginning of the 17th century, this cultural tradition was to be revived with a wide range of sheep farming , which found its place mainly on the farms and in closed societies. Idylls were staged, summer days were celebrated with less strict etiquette in the open air. Shepherd games , the opera , gallant poetry and their own production of novels carried the fashion, and nurtured the feeling that a far happier life could exist outside of the strictly regulated coexistence in town and court, or at least it could have existed in distant antiquity.

An almost opposite tradition of thinking about nature existed with the Christian doctrine of creation, which had to be considered the most rational position in Europe until the end of the 18th century. While in other cultures (according to the European perspective) one assumed senselessly long historical traditions, in Europe one lived with the rationally manageable historical space that proved itself with traditional buildings and documents. Judaism and Christianity came together here in the historical perspective: The world was around the year 3950 BC. BC (the dating could differ slightly depending on the interpretation of the Bible). Adam invented the language on the first day and named the animals. The fall of man , which ended for Adam and Eve with the expulsion from paradise , brought the bigger step into culture . A "natural state" was given in this model to some extent. According to the theory, we could not go back into it because of original sin . To get rid of all clothes, to live naked together, seemed in fact hardly an option, everyone felt the shame that would have to be overcome here. It had come up with the Fall.

The philosophers of the 17th and 18th centuries assumed that Adam immediately began with the construction of cities, means of transport and all practical facilities of life - for this he needed no more than the human ability to put ideas together to create new inventions.

According to God's punishment, the antediluvian culture fell around the year 2300 BC. Chr. Victim. The three sons of Noah repopulated the world. In the 17th century there was a debate about whether all the peoples actually met again to build the Tower of Babel a few centuries later . It seemed more plausible that the linguistic confusion concerned only the oriental nations, while the other languages of the world diverged from one another in their own language developments. One did not have the historical space to allow an event of such significance so late - the details are of interest because they only left limited space for philosophical considerations of a natural state that preceded the culture.

Philosophical Theories

The philosophical theories that were formulated in the 17th and 18th centuries with a view to the natural state tried to gain plausibility in various of the traditional lines available. Another argumentative area should become interesting with the non-European cultural contacts: that of the discussion with "wild" peoples and that of an explanation of Chinese culture.

Jesuits at the end of the 17th century assumed that China still preserved most of the antediluvian civilization of all cultures in the world. Apparently only the idea of Old Testament God was lost here. China lived in a philosophical atheism , according to the idea spread by the Jesuits, in order not to have to position themselves against the Confucian rites at the Chinese court (see the article rites dispute in more detail ). Otherwise nowhere as here was the order of the world, from which Noah still descended, was preserved. Europe, Africa and America, on the other hand, underwent stages of barbarism after the Flood, from which they freed themselves to varying degrees.

The peoples of the world played a minor role in the arguments on which Thomas Hobbes referred with the Leviathan (1651). They only began to add complexity to the picture in the treatises of John Locke ; in them one finds side glances at travelogues with the notes of which foreign forms of coexistence were brought closer. In the second half of the 18th century, studying the indigenous people of North America was to re-inspire the discussion of the state of nature. At the turn of the 19th century, the possibility of happy designs for a natural coexistence sustainably nourished the cultural pessimism of Romanticism .

Hobbes and the brutal state of nature

Hobbes' Leviathan (1651) was based on very fundamental considerations about the materiality of the observable world. Unlike in animals, in humans the matter of existence becomes conscious. At the same moment that man realizes that he exists, he can foresee that everything he can gain will be of no use to him should he lose his life. This alone fundamentally defines its nature. It forbids him to subordinate himself to a community in the consciousness of his own existence: Society must subordinate its life to the good of all others. As a result, if man shows himself in his natural state - in emergency situations in which order is lost and all laws cease to exist - inevitably a " war of all against all ", an attempt by all individuals to assert their right to exist against the interests of others. (Hobbes does not assume that there was ever an epoch before civilization in which all people were at war with one another, but his considerations understand emergency situations as those in which the natural state broke the ground. In them, that reigns very quickly “Natural right” that everyone has to defend his life and no more law.) The catastrophe of living together in open civil war is prevented in practice by the establishment of a monopoly of violence . Only when people live together under self-imposed force majeure can cultural achievements be realized: building communities, expanding infrastructure, and collecting wealth as a collective.

Hobbes' reflections on a natural state of mankind followed logically diverging basic assumptions. Since Descartes Meditations (1641) , at least since Descartes' Meditations (1641), it was no longer possible to argue that people are aware of their existence . Linking the absoluteness of one's claim to existence to the certainty of one's existence was a step beyond Descartes, but above all it was an attack on Christianity , which propagated its own theory of the corruption of human nature and the doctrine of sinfulness of man used to justify the claims to power of state and church in response to human nature.

Hobbes argued without a fall from grace and ultimately without a moral . The man he thought out acted naturally and reasonably justified, even when he went to war against the rest of humanity:

|

However, no one should accuse human nature at this point. Man's desires and other passions are not sins by themselves. They are no more than the actions that spring from these passions before one takes notice of some law that forbids them: which in turn cannot be done until some law is passed: which in turn cannot be done before one is up a person agrees to make the law. (transl. os) |

It is only the law that is oriented towards the problems raised by the state of nature, an entirely human law, that creates the options under which we can judge human actions morally.

The argument put forward could not count on a broad response, since it shared the image of man with the Church, but granted it no further role in the legitimation of secular and ecclesiastical power. Hobbes was decried as an atheist and enemy of mankind and triggered a wave of philosophical counter-models, all of which justified the absolutist state , for which he himself had stood in the turmoil of the English civil war , with references to the state of nature.

In the second half of the 17th century, Samuel von Pufendorf formulated the essential consensus formulas on the state of nature and on the state that had to build on it . The philosophers who defined the broader counter-positions to absolutism as to Hobbes in the English political debate had the more lasting influence on the debate.

An answer to Hobbes and the Glorious Revolution

The philosophical debate that followed Hobbes kept the chance of being able to argue independently of the Christian image of man in the game, but looked for a new opposition opportunity. First of all, there were reasons for this in English domestic politics.

Hobbes had based his considerations on the civil war that had broken out shortly before with the beheading of Charles I. If the monopoly of violence collapsed, the "war of all against all" would break out, so the lesson of the state philosopher who argued for Charles II and against the religious tyranny of Cromwell from France.

Locke and Shaftesbury were partisans of the Whigs , the supporters of Parliament that sparked the second revolution of the 17th century in 1688. It was to be called the " glorious " one, since this time England deposed the regent without the catastrophe predicted by Hobbes - and installed a new one with new powers over which Parliament and its voters watched. The new model required its own philosophical position. John Locke formulated it in 1689 with the Two Treatises of Government . He came to an agreement with Hobbes on the merging of people: This happened out of a natural state. Locke, however, became more concrete and historical: the people realized that they could tackle larger projects in community. States emerged from patriarchal associations. These, in turn, should be viewed as contracts that were concluded to enable better coexistence. In an emergency, these treaties had to include a right with which rulers could be deposed - namely if they endangered peaceful coexistence and general prosperity. Locke argued in this regard with a view to the multitude of known states and forms of human coexistence. A glance at the inhabitants of Brazil had to make it clear that there were very different options from which to choose the happiest possible.

Locke's younger colleague Shaftesbury formulated the revolution in the image of man with the theorem of a human being who lived happily together in a natural state. The attack on the church came from the other side: Shaftesbury's man was not marked by sin, he was also by nature altruistic . At a completely different point, the author brought religion on board: he consistently argued under the thesis that God, as a perfect being, could only create the best of all worlds . In the great “system” everything that we perceive as imperfection shows itself in the perfection aimed at by God. The calculated catch in the argument was that man could not recognize this system in its complete perfection - the problem solution was a person who was naturally endowed with a sense of harmony, whose moral side was a special " moral sense ". By nature man strives to live in harmony with the cosmos and what he sees of nature.

These considerations were not about celebrating the lives of indigenous peoples - Shaftesbury assumed that they were possibly far too poor in resources to allow man to develop his nature. What was new with Shaftesbury's argument was the view of the existing coexistence in the state of civilization : Where this was determined by violence and discrepancies, it was because the existing culture prevented the development of the innate sense of harmony. The state and the church, in the same argumentative turn, became responsible for the selfishness they fought so hard. A better culture would appear less resolute with punishments and rewards that at the same time corrupt people less and develop their sense of morality and harmony .

From the 18th to the 19th century

Rousseau, the irretrievably lost state of nature

Rousseau's considerations go only to the premises and political conclusions, not beyond Locke and Shaftesbury. However, they should lead to a completely different way of thinking about the state of nature: Rousseau postulated Shaftesbury as a person who sought harmony with nature in the state of nature. With Locke he showed an interest in the forms of human coexistence. With the researchers of his generation, however, he paved the way for existing primitive peoples to be able to be closer to the natural state. At this point the argument broke away from the theory of the state to which Rousseau himself ascribed it with the Contrat social (1762).

While the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Europe showed a movement towards much stronger state associations, it became interesting to think about the state of nature as an opposing position to European civilization . With his Description d'un voyage autour du monde (1771), Louis Antoine de Bougainville , with a Rousseau-trained view of the state of nature, pioneered the new idealized image of the South Sea islanders. At the moment it was published, Denis Diderot was still motivated to write his Supplément au voyage de Bougainville , a defense of sexual freedom. The new image of the South Seas had a far greater effect on European artists of the 19th and 20th centuries, on the perceptions of the painters Gauguin and Nolde and, along with these transfigurations, on Margaret Mead's cultural anthropology .

The harsher variant of a life in a natural state was realized with the descriptions of North American Indians, who for the Romantics became models of natural freedom. Images of a new approach to nature shaped by masculinity led to a break with the wig-wearing “effeminate” 18th century, which only lacked the word Rococo .

The scientific examination of the state of nature found an additional impetus with the theory of evolution in the middle of the 19th century . With it began, in the expansion of the romantic and ethnological view of "primitive peoples" and peoples who should succeed in a better life in harmony with nature, a biological research into the state of nature. Under the perspective that was only developed on a broad front in the 20th century, humans had lived as hunters and gatherers for millions of years. He entered the state of culture with a biological endowment to this and not to our life.

Hegel: another conceptual approach to the state of nature

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel mentally approached the state of nature in a different way. Hegel imagines two human individuals who, as thinking beings - but still without self-knowledge - meet for the first time without any previous social experience and thus meet another human individual. The absence of anything social is a simplification compared to reality, which is supposed to reveal the innermost, original nature of the human being in the further thinking of the situation. According to Hegel, the two "first people" now enter into a life-and-death struggle for pure recognition , which continues until one of the opponents out of love for his life recognizes the other as master and continues to live as his servant. To risk one's own life, to risk it more than others, is the source of freedom in Hegel's philosophy. The desire for or the struggle for the completely immaterial good of recognition is the strongest drive of people and also the motor of a universal story that, after several steps of the emergence and resolution of social contradictions, finally leads to the end of history and the "last man" leads.

What is remarkable about this approach is how it differs from Hobbes' philosophy. Where Hegel sees the struggle for recognition as a prerequisite for freedom, Hobbes recognizes the lust for fame as one, if not the source of evil per se. However, there is one thing in common: Hobbes and Hegel both recognize the original state as not ideal. Hobbes allows people living in the original “Warre” to long for a way out of the struggle of all against all, that is, not to be naturally evil and thus not “made” for the struggle of all against all. Similarly, Hegel describes how neither the master nor the servant are satisfied with their existence. The master is soon no longer satisfied with recognition from the servant: he wants recognition from another master and thus has to risk his life again in further struggles for recognition. The servant also longs for recognition and finds this in his work and the mastery over nature acquired through it. Only the mutual recognition of citizens in democracy resolves all contradictions in Hegel's philosophy - at least in the interpretation of Alexandre Kojève . For Hobbes and Hegel, people therefore live in a later than the natural state in a society that corresponds to their most elementary nature more closely than the natural state, and therefore experience greater satisfaction. However, the form of government in which the greatest satisfaction can be achieved is completely different. The monarchy or absolutism that Hobbes demands is only a transitory state for Hegel. The reason for this is that, in contrast to Hobbes, Hegel does not assume that the desire for recognition can be suppressed entirely from outside or through self-control. Hobbes' image of man differs little from Homo oeconomicus : the drive to accumulate material goods for their own sake never ends and is sufficient for the limitless individual and social accumulation of wealth. Striving for recognition is not necessary as a drive - on the contrary - it is in principle detrimental to the general welfare.

It is not entirely absurd to see the strong belief in the closeness to reality of Homo oeconomicus linked well into the 20th century with the great importance of Hobbes for the modern understanding of the state. Among other things, empirical economic research (cf. game theory ) over the past three to four decades has shown the need to correct the image of man in the Hegelian sense.

20th century and present

What began as a philosophical argument and was caught up with by 19th century research developed in the 20th century mass movements - from those of the trivial Darwinist oriented National Socialism , philosophizing about the role of the human races from the state to the extended arm of the further " natural ”selection up to the diverse movements of the“ dropouts ”who propagated a“ back to nature! ”as a rejection of western consumer culture .

Thinking about the state of nature for which man was created became a matter of course. What kind of nutrition is human evolution equipped for? What damage does it suffer from the current eating habits? What group size determined human coexistence in the course of evolution? What civilizational problems does the anonymous coexistence of people in big cities pose?

The reasoning remained fundamentally intact, with differences between a state for which we were created and a state in which we live in contrast. The ensemble of science interested in these differences expanded. Since the generation of Arnold Gehlen, the philosophical debate has tended to face the subject of debate that it created itself with critical reflections. In retrospect, the state of nature is, to a large extent, a fictional object. In its numerous forms it was subject to changing political and cultural requirements, to which it offered itself flexibly and credibly in its rejection of existing (especially religious) perspectives and its links to lines of tradition and cultural experiences that were independent of them.

References

- ↑ Lit .: Leviathan , 1, chap. 13, p. 62.

literature

Primary literature

- Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, or The Matter, Forme, & Power of a Common-Wealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil. By Thomas Hobbes (London: A. Crooke, 1651), part. 1, chapter XIII, "Of the Natural Condition of Mankind as Concerning Their Felicity and Misery." Internet edition Bartelby.com

- John Locke, Two Treatises of Government (1690), The Second Treatise of Civil Government, chapter II. "Of the State of Nature." Internet edition Constitution Society

- Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury, "Inquiry Concerning Virtue or Merit" [1699], Treatise IV of the Characteristicks (London, 1711).

- [Anonymous], Les avantures de ***, ou les effets surprenans de la sympathie, vol. 5 (Amsterdam, 1714). - German: Liebs-Geschichte des Herrn *** , Vol. 5 (Franckfurt / Leipzig: AJ Felßecker, 1717).

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau, answer to the prize question from the Académie of Dijon: "Source est l'origine de l'inégalité parmi les hommes, et est-elle autorisée par la loi naturelle?" Treatise on the origin and basis of inequality among people ( 1755).

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Du Contrat social (1762).

- Arnold Gehlen, primitive man and late culture (Bonn: Athenaeum, 1956) / (Frankfurt am Main: Klostermann, 2004) ISBN 3-465-03305-1

- Irenäus, Eibl-Eibesfeldt, The preprogrammed person. The inheritance as a determining factor in human behavior (Vienna-Zurich-Munich: Molden, 1973).

Web links

- Ulrich Eisel : State of nature. In: Basic Concepts of Natural Philosophy. Research facility of the Evangelische Studiengemeinschaft e. V., 2012, accessed on July 17, 2014.